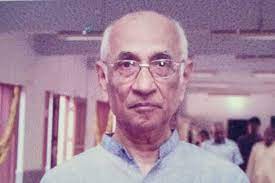

“Maintaining good communal ties in Goa is a crucial issue”, said the late Naraina Sinai Dumó (a.k.a. Narayan Sinai Dhume), in a chat with Óscar de Noronha, on the radio programme Renascença Goa.

Use the following link to listen to the original chat in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=renascenca+dumo

ON – Let’s talk about a very important period in the history of Goa when the Dumó family had three diplomats. What information can you give us about this?

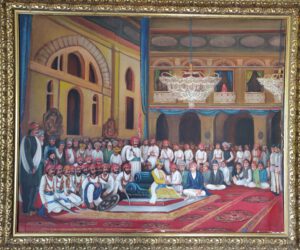

NSD – I only remembered now, at this moment, that there was a pamphlet published by Dr Panduronga Pissurlencar of the Historical Archives, titled Agentes Hindus da Diplomacia Portuguesa (Hindu Agents of Portuguese Diplomacy). And he indicated some characters; for example, the first one was Vitogi Sinai Dumó. It seems to me that Vitogi’s appointment was more due to his knowledge about the negotiations between the Portuguese and the Indians…

ON – Do you mean the Peshwas?

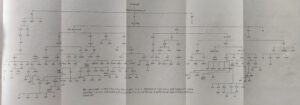

NSD – The Peshwas! So the first was Vitoji, and he certainly lived in Poona; next was his son, Panduronga Sinai Dumó, and the third was Narana Sinai Dumó, whose name I bear. And he lived and worked in Poona.

ON – So, three generations!

NSD – Yes; the grandfather, father and son! And it seems to me that besides their knowledge of diplomacy, they spoke Portuguese very well. This is a great fortune. And he knew the Marathi language very well, so he could converse directly with the Peshwas. And it seems to me that during these three generations the conversations were limited to the exchange of Dadrá and Nagar-Haveli. I have heard that one of the streets of Nagar-Haveli is named after Narana Sinai Dumó.

ON – And how would they have learned Portuguese?

NSD – This is a big question mark, because there were no schools then. For me it’s an enigma. But one very important thing: my Philosophy teacher at the Lyceum used to say, ‘One learns to speak by speaking; one learns to write by writing; one learns to dance by dancing….’ This is a motto I’ve followed throughout my life, to learn languages.

I was in the Netherlands for almost six months, where I was a scholarship holder of the World Health Organization. Just through the practice of talking to the office staff I learned a little Dutch and then I understood that the best way to learn any language is to speak. Don’t go to its grammar: that doesn’t help – you won’t learn to talk. So, just talk, listen… have a keen ear, that’s it!

NSD – Oh! But I did have a problem. I mean, after passing the 4th standard in a Marathi medium school, the first-born would switch to Portuguese, because he had to look after the landed properties, even if they were small. The system was as follows: if you wished to deal with the Portuguese officers, you had to learn Portuguese… and then some students would switch to English. I continued with Portuguese until the seventh year of Lyceum.

Hindus were very few. At the Lyceum, the composition was as follows: some were Europeans, children of officers, for example, the Secretary-General… I still remember the names of certain officers, like Pamplona de Corte-Real who was a secretary-general; another one was Rui Guimarães… Then there were the Christians, or, the apostolic Roman Catholics; and very few Hindus, but there was representation. Let’s say, in a group of thirty there were at least eight or nine. That was the composition.

Among those nine or ten, at least one went to Portugal. And in this small percentage I remember Narana Coissoró, who was Speaker of the Portuguese Parliament and university professor…

So that was the composition; and I belong to the last batch of that composition.

ON – But why were there so few Hindus at the Lyceum? Where did others study?

NSD – Because they always thought that the best avenue for employment was neighbouring India. Portugal could offer nothing but a clerk’s job, and these jobs were so very few. Industrial development and things like that weren’t even heard of. So they launched out in India for employment. And many Christian Goans went into the merchant navy, and others, the Hindus, went into the civil professions.

FAMILY ORIGINS

ON – Is the Dumó family from Goa, and originally from Cumbarjua?

NSD – Originally, we are from Cortalim; we are members of the Comunidade (village agrarian community) of Cortalim. We left when the first conversions took place; at the location of the first church established in Cortalim was the Manguexa temple and was destroyed. My father wrote a book after he retired: he went there and measured the dimensions. They are exactly like our temple [now located in Mangueshi].

ON – So, the temple that was subsequently built in Mangueshi [Ponda taluka] has the same dimensions! That’s interesting!

NSD – Not only interesting; but new horizons of our past are being discovered. It is indeed very interesting. You will see that there are still some Catholic families that hold their past intact: they were Sardesais, Cuvelcars, Camotins, Dumós…

ON – Do you know Dumó families converted to Catholicism?

NSD – No; but I’ve only heard that some of the Dumós who converted to Catholicism were called Saldanhas! Someone told me so, but I don’t know anything more about it. But there are some families – very few – that have preserved their old data where they find their roots. It’s a great joy.

Now, note one thing: in this effort to trace the past, it is worth entering into the field of genealogy. A friend of mine told me that a colleague of his, a student at the Art School, was called Maendra Álvares. His mother called her son’s friends and explained the origins of the families…

ON – The Álvares are from Loutulim; and Maendra Álvares’ mother was a daughter of Gomes Pereira!…

NSD – Oh, really?! From Divar! He was our family lawyer, a good family friend…

CONVERSIONS

ON – What do you have to say about the friendly relations between the various communities in Goa?

NSD – Oh! That’s a very interesting chapter! First of all, the priority of Europeans was the conversion of the Brahmins. Brahmins exercised a preponderant influence. It’s not that in every case there was violence and the Inquisition and things like that. Conversions also took place of their own free will. And why did they convert? Because they were offered large landed properties… You may offer some other explanation, but I think – as long as there is no other plausible explanation – that they were ready to convert attracted by those properties…. Or else how do you explain the existence of such large landowning Catholic families in Goa?

ON – Well, they are families that turned rich much later, in the 19th century, and not at the time of the Conversions [16th century]… And similarly, among the Hindu community, there are still large landowners: the Quencró [Kenkre], the Dempó, the Cundoicar [Kundaikar], the Viscount of Perném…

NSD – Well, the Quencró, the Cundoicar, and, oh yes, the Viscount of Perném! That’s true…

FRIENDSHIP AMONG COMMUNITIES

ON – We were talking about friendly relations….

NSD – Yes, these friendly relations… Well, look, you’ve come here… and I’m keen on hearing this… from the mouth of the Catholics…

ON – A dialogue is the need of the hour!

NSD – Oh, yes! During my life at the Lyceum, I always thought: why does this priest have such a great affection for me? He wasn’t my teacher. I’m referring to Father Armindo de Santa Rita Vás. Later, I learned that my father was a great friend of his father… The relationships were so close that, in those days, you know, a little favour done carried a lot of weight, a lot of weight…

ON – There was that feeling of gratitude!

NSD – Ah! that’s it! (cries) Once, when I was in the 5th Year [of Lyceum], Father Armindo said to me: ‘Look here, Dumó, listen! Would you like to go to Portugal?’ … ‘Portugal!’ My God, I was shocked. Why? Because amid the Hindu families, there was great apprehensions that one’s children would go to Portugal, stay there and get married – and live there all their life. That’s because everyone who went to Portugal to study got married there, stayed there and never returned to Goa. Never!

ON – Have you been to Portugal or not?

NSD – After my retirement I went twice. I really liked it. But I didn’t get to see what I wanted to see. I had a bucket list. But I’d lost contact with my friends in Portugal. So going around in Portugal was difficult. For example, I wanted to visit and see things at the University of Coimbra… Lisbon, not so much; and some hospitals, one of those where Dr Mortó Sardesai worked: he was the Director of the Pathological Laboratory in Lisbon. And I especially wanted to see Penedo das Saudades, in Coimbra.

ON – How can this friendship that existed in Goa, between communities, continue this friendship?

NSD – Ah!!! It’s a very crucial question. You see, during my days as a bureaucrat – I was in the Indian administration from 1963 to 1997, in the Health Services, first as a Rural Medical Officer and then as State Nutrition Officer – I was the first and last one, because after my departure the post was abolished. And during that time I fought a big battle with them all. Many, on listening to my story, would love to hate the Catholics – talking about communalism, and things like that….

But let me say one thing: on this path, until the last day, I had the strong, unshakeable backing, a bulwark, in the person of a Catholic: Senhor Abel do Rosário, who was Under Secretary. I salute him! He never bowed to the influence of this and that, especially of religion and community; he went by the law, and always supported me. But the political forces were so sinister that they didn’t want to take the straight path. That’s a long story; it will take a few days to tell. But I would like to tell so that it is on record.

A PAST DESTROYED

ON – We’ve already bothered you a lot!

NSD – No, no! It’s a pleasure; this is a tonic! I am very happy, very pleased to see that there are still people in Panjim – in Goa – who speak Portuguese. Why do these people want to fight the Portuguese language? They embrace English so easily, and don’t want to accept Portuguese? Why? Portuguese is a language, after all. And there are liberal elements in Portugal, without which the democracy that exists in Portugal today would not have been there.

Wait a minute; I’ll tell you a little story. When Dr Mário Soares came here on an official visit, as President of the Republic, my father was taken there to the President; and he took this book about the Dumós of Goa, gave it to him, and he kept leafing through it…

‘I don’t understand; I don’t understand anything. Why didn’t you write in Portuguese? Then I would understand and appreciate.’

‘Look, Mr President’, said my father, ‘there are thousands of books in Portuguese translated into English, and vice-versa; but there is no book translated from the Portuguese into Maratha, to show the important role that the Portuguese played in Maharashtra. The whole story only revolves around Goa, Damão, Diu, Dadrá and Nagar-Haveli!… There is nothing. Tomorrow, if there is someone interested in writing history, or in translating, what do we have! We have nothing! So, I did whatever I could do, despite my limitations.’

He got up and hugged him.

And he said: ‘This whole vast Indian continent is open to you all. Why is it that instead of receiving you with open hands, we are going to receive you at the point of the sword?

Dr Mário Soares was agonised. He said: ‘The whole of our past built over so many years was destroyed within a few minutes, a few minutes!’

(First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série – No. 12 Sep-Oct 2021, pp. 49-52)