Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 3/6)

Welcome Break

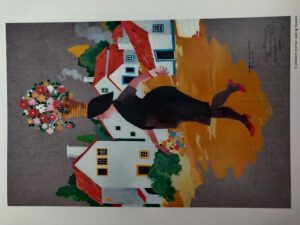

Mário’s diaries were sacrificed on the altar of newspaper cartooning. In 1959, the caricaturist flew to Lisbon on a Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian scholarship.[28] He toured the length and breadth of Portugal, distilling the essence of the Portuguese soul into his sketches and drawings. The experience brought a fresh perspective to his profession:[29] it whetted his appetite for travel and charted a path that would reveal itself with time.

It is unlikely that Mário would go out of his way to confer with the Portuguese cartoonists reeling under an authoritarian regime at the time. In London, later that year, he met with Ronald Giles, Raymond Jackson (Jak), Victor Weisz (Vicky), and memorably bumped into his all-time favourite Ronald Searle at a pub on Fleet Street! He was happy to do cartoons for the classic humour magazine Lilliput and for ITV, but featuring in Punch, the flag-bearer of humour magazines, really was the icing on the cake.

Mário’s passage to England was a turning point in his career. He earned money and friends; more importantly, Searle’s injunction – ‘Stay on in England, but stop copying me!’[30] – infused him with the confidence to go it alone. But then again, the dramatic regime change in Goa, on 19 December 1961, made him turn on his heels. He returned to Bombay on an Indian passport and rejoined the Times Group; but this time around, R. K. Laxman, the reigning deity of The Times of India, ‘subtly ensured that the pedestal was not for sharing,’ says journalist Bachi Karkaria.[31]

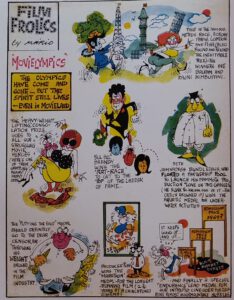

Appreciating the steady stream of cartoons that Mário had sent home while on his working holiday abroad, Bombay’s Cocktail magazine commented: ‘Mario is so well known that it’s difficult to say things about him that will not be superfluous. A man who can draw and depict the funniest in the most convincing manner, his Shammu has won the laughing interest of everyone. Every cartoon of his is a refreshing experience. He lampoons the frailties, foibles and social shortcomings of us all. His hilarious work is packed with characters from the contemporary scene and his greatest gift is that he makes us laugh at ourselves. His illustrations too have polished perfection and have been such a success that all our writers want Mario to illustrate their work.’[32]

In Mário’s absence, Jean de Lemos, an artist born in the Nilgiri heights, handled the bulk of illustration; they had a soft spot for each other and even exchanged sketches (Figure 3).[33] On his return, though, Jean learnt that Mário was getting engaged to Habiba Hydari,[34 a 24-year-old fine arts student-turned-air hostess whose ‘teenage gang’ had once been part of his circle.[35] Jean exited, but remained friends with Mário’s family.

On 10 November 1963, Mário and Habiba[36] got married in a civil ceremony, and set up home at Rockville. Their children, Raul,[37] a hairstylist, and Rishaad,[38] a designer-decorator, who live in Loutulim, remember their mother as ‘the boss’ and their father as a calm, liberal, and generous man.[39] Mário for his part rued the fact that he was usually too absorbed in his work to resolve pressing domestic issues with a firm hand.[40]

Versatile Artist

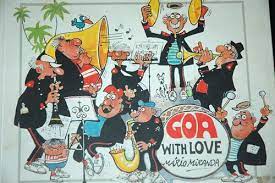

In 1964, Mário brought out a book of sketches, Goa with Love,[41] dedicating it to Habiba. His visibility was on the rise – in school textbooks, corporate calendars, advertisements and trendy magazines. Successive editors of the Weekly[42] held Mário in high esteem; and humourist Behram Contractor (alias Busybee), political commentator Vinod Mehta, poets Dom Moraes and Nissim Ezekiel, and admen Gerson da Cunha, Frank Simões, Bal Mundkur and Alyque Padamsee were among his closest friends. They churned out reams of prose and loads of ad copy; Mário read between the lines and came up with charming visuals.

Mário’s reading, now restricted to periodicals, stood him in good stead.[43] Victor Rangel-Ribeiro believes that the cartoonist’s stays overseas, ‘particularly the long months he spent in London, plus the fact that he was very well read in Portuguese as well as English literature, did give him a broader outlook than one normally found in members of the local press.’[44] But Mário wore none of that on his sleeve; in fact, he abhorred ‘intellectual talk’, his forte being ‘the accumulation of trivia judiciously and harmoniously composed,’[45] as Vinod Mehta puts it.

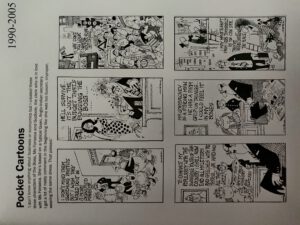

That is evident from Mário’s daily cartoon strips, some of which drew upon people he met in daily life: the archetypal secretary, Miss Fonseca; the Boss and his hapless minion Godbole; the fat, corrupt politician Bundaldass with his sidekick Moonswamy, and the bosomy Bollywood star Rajani Nimbupani.[46] Millions across generations grew up on those cartoon characters that were all the rage; they are now etched in the collective memory, even if the world’s ever-changing sensibilities tend to put a negative spin on some of them.[47]

Nineteen seventy-two was a landmark year: the United States Information Service (USIS) flew Mário to America, and Tel Aviv invited him to stop en route. He met Israeli cartoonists Kariel Gardosh, Shemuel Katz and Friedel Stern; and in the US he interacted with Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts; Herblock, editorial cartoonist of the Washington Post, Pat Oliphant of the Denver Post, Ed Fisher of The New Yorker and freelancer Al Jaffee. Mad magazine featured him, and back home Mário wrote a piece titled ‘Cartoons – American Style’[48] – a pointer to his writing talent[49] lost in the rough-and-tumble of editorial cartooning.

As India was beginning to see him in a new light, Mário lamented the tendency to seek validation from agencies abroad[50] and wept over his countrymen’s inability to laugh at themselves. He regularly discussed the state of the profession and, Alexyz recalls, he encouraged budding cartoonists. He inspired the formation of the Indian Institute of Cartoonists, Bangalore, and gifted them many of his priceless originals.[51]

Mário was among the handful of cartoonists[52] that ruled the roost in India, but alas, long years of caricature art had left him with little leisure to pursue what he liked best: sketching. The reprinting of Goa with Love in 1982 was thus as much a celebration of the fast-fading world of his youth as it was an evocation of the line art that had grown on him.

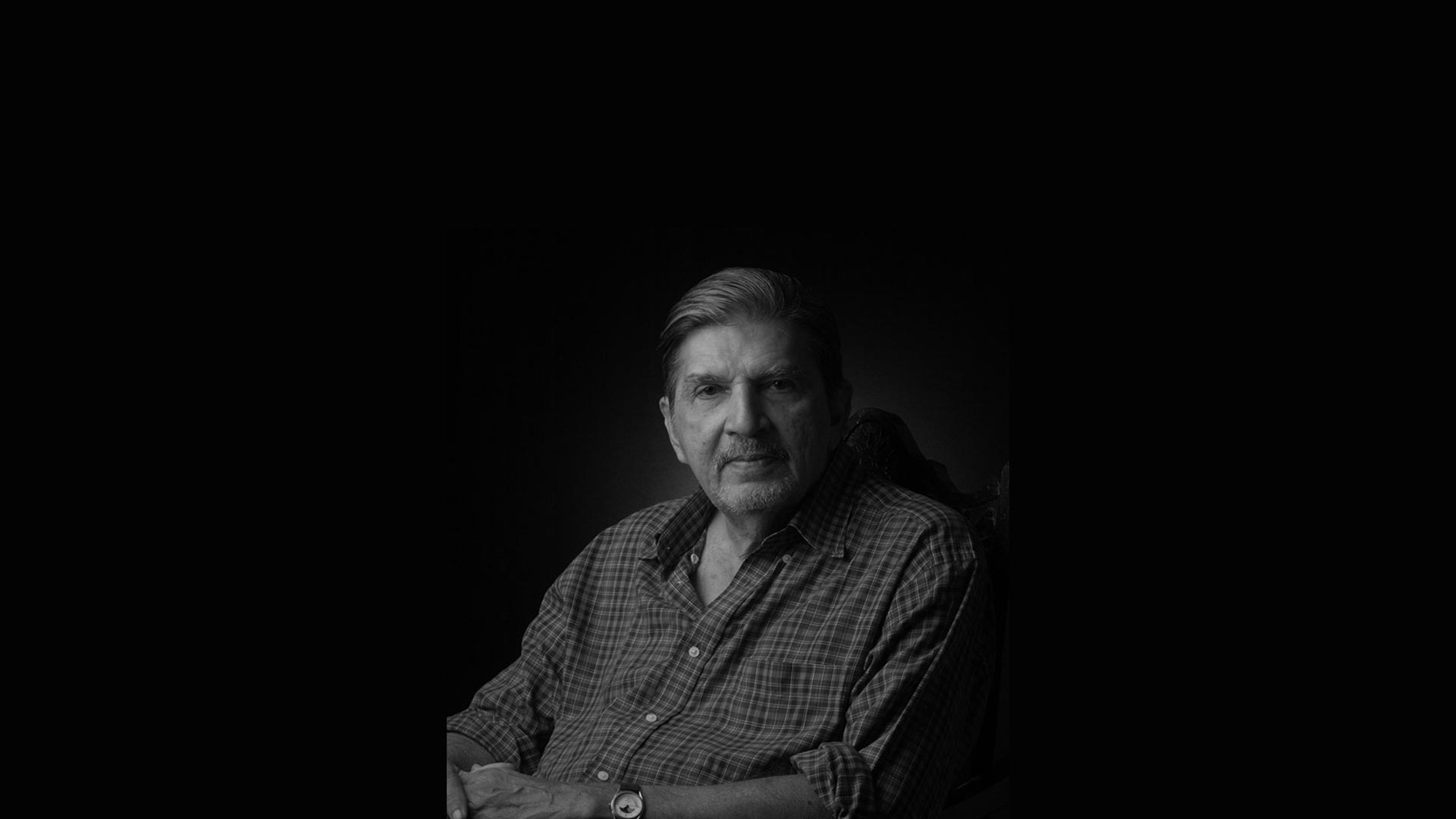

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[28] The scholarship possibly came as a result of Maria Zulema’s letter to Minister Pedro Teotónio Pereiras. Mário lived in a rented room on Rua Actor Isidoro. (Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.6.2021)

[29] Published in Diário Popular, cf. ‘M de Mário’, by Jorge Silva, in Macau, April 1993, II Series, No. 12, pp. 39-43.

[30] ‘The Last Interview’, op. cit.; FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.; ‘Tale of Two Goans’, op. cit.

[31] https://indianjournalismreview.com/2011/12/12/did-r-k-laxman-subtly-stifle-marios-growth/ Retrieved on 8 August 2021.

[32] Cocktail, January 1960, p. 5.

[33] Mário called her Chips; she called him Popat (Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021)

[34] Daughter of Iqbal Hydari, a senior executive of the Indian Railways and scion of the nobility of Hyderabad, and Rohaina Mohamedi, a painter.

[35] Mário’s circle included Lúcio Miranda, a third cousin, and Sarto Almeida, both architects. Cf. Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 17.

[36] He called her ‘Charlie’, and she called him ‘Joseph’.

[37] Married Magen Gilmore, who lives in the US with their daughter Gayle Zulema.

[38] Married to Sabine Frank, who lives with their children, Rafael and Samuel, in Austria.

[39] Personal interview on 9.7.2021.

[40] As told by Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021.

[41] There are at least three known editions of Goa with Love (1964, Times of India, Bombay; 1982, Goa Tours, Panjim; 2001, by M&M Publications, Reis Magos). In 1964, Mário also brought out ‘Goa Postcards’.

42] Khushwant Singh, M. V. Kamath and Pritish Nandy were the last three editors of the Weekly.

[43] All India Radio, Bengaluru, interviewed by Shylaja Gangooly, 27 Nov 1993. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kDDO3N4OVtA

[44] Email of 10.7.2021

[45] Vinod Mehta, ‘Tomorrow is another day’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 139.

[46] Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[47] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/sunday-times/kerala-to-us-cartooning-is-in-the-crosshairs/articleshow/69805457.cms Retrieved on 22 Aug 2021

[48] The Illustrated Weekly of India, 2 January 1974.

[49] Mário liked to write (B. Contractor and K. Singh encouraged him) but found it ‘a slow and irritating process’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zJB0u-_akA

[50] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[51] https://www.deccanherald.com/content/211335/cartoon-gallery-gets-mirandas-priceless.html

[52] K. Shankar Pillai, R. K. Laxman, O. V. Vijayan, Abu Abraham, Rajinder Puri, E. P. Unny.

Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 2/6)

The Artist as a Young Man

The Artist as a Young Man

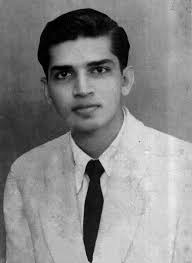

It was during his college days in Bombay that Mário’s characters first strutted out of his diaries; he drew pocket cartoons and peddled them at Flora Fountain for pin money.[11] And at a medical ball held at Clube Vasco da Gama, Panjim, couples dancing the night away delighted in the frisky sketches of the faculty members that Mário kept drawing on the wall mirrors lining the ballroom.[12]

It is not that Mário always passed uncensured. One day, a priest from the village, whom he had depicted outside the local fish market, showed up at his house. Mário’s mother, after doing her best to placate the visitor, ended up going to see archbishop Dom José da Costa Nunes, who had once expressed his wish to meet the young artist. Mário was hesitant but once there, was relieved to see his diaries spark guffaws rather than a controversy. ‘That was the first time I was appreciated by someone I didn’t know,’ he said.[13]

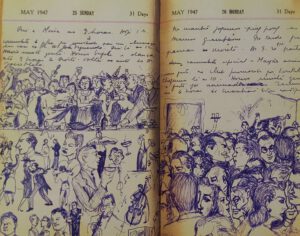

Mário maintained a diary right through his years spent in British India with intermittent stays in Goa and Damão (Figure 2). The last three logbooks (1949-51),[14] now available in print, are a shrine of frolicky pictures of relatives and friends in Loutulim, Panjim and Margão.[15] To quote Nissim Ezekiel, ‘the buffoonery of his human figures is redeemed from grossness by their verve, their inner urge towards going places, getting somewhere. It is not always their fault that there is no place to go, nowhere to get except through the corridors of illusion.’[16]

That was Mário’s equivalent of the dark night of the soul! His lifestyle was a cause of concern to his by now widowed mother struggling to manage the household while at the same time providing for Pedro at Princeton University.[17] But then Mário had a change of heart: was it the showcasing of his watercolours and drawings by the 1950 Souvenir of the Bombay-based Loutulenses League[18] that did the trick?

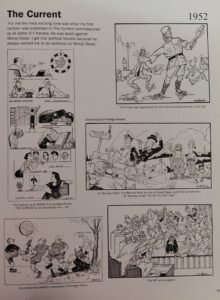

In 1951, seeing a bleak future for himself in Goa, Mário moved to Bombay. Though creative possibilities seemed unlimited here, he was jobless and quite badly off at first. That’s precisely when Policarpo (Polly) Vaz, a fellow hosteller at Rockville,[19] famously suggested to him to hand-craft picture postcards depicting the city monuments, offering to sell them at the hotel where he worked the night shift. Needless to say, the two became fast friends; and they had even thought of migrating to Brazil,[20] when Mário got a call from D. F. Karaka of The Current. The redoubtable editor, riveted by Mário’s diaries, commissioned him to cover a can-can dance scene at the Taj Hotel, and received such a rib-tickler that he promptly took him on as the tabloid’s regular cartoonist.

The young Goan created a stir in Bombay's journalistic circles when his cartoons first appeared in the press. Editor C. R. Mandy and art director Walter Langhammer soon invited him to The Illustrated Weekly of India. Before long, other Times Group publications,[21] too, began to use Mário’s drawings; they skilfully portrayed movement and sound, and often featured the cartoonist’s trademark dog.

Art of Cartooning

That was the year 1952. Mário had virtually stumbled into the profession of cartooning.[22] To an onlooker the job seemed easy, and everything grist to the mill – from the bureaucracy, fashions, business, and people’s habits, to the animal world, environment, music, society, and even politics – but really, finding humour was no mean task. ‘There are times when you don’t feel funny, or may not feel like laughing, but still have to produce a funny cartoon – like a clown who has got to make people laugh all the time, although he doesn’t feel like laughing.’[23]

Elaborating on his predicament, Mário said, ‘People expect me to come up with jokes and anecdotes to make others laugh. I can’t do that. I enjoy humour if it comes from someone else who knows how to tell a good joke…. I am not a naturally funny person; I may look funny, but I am not funny.’[24] And if a cartoonist’s defining quality it is ‘to detect funniness in people’s behaviour or physical features and draw it, it is equally important to be able to laugh with someone, not at someone, without being cruel,’ said Mário, adding: ‘Humour is something very personal, individual. What’s funny to me may not be funny to you. Sometimes I do something which I think is very funny – and it flops! And people asking you to explain a cartoon flattens it completely.’[25]

Past the initial scramble for work, Mário began to yearn for the blissful spontaneity of his diary sketching. Add to this the fact that political bigwigs were breathing down his neck, and Mário had a sure recipe for disenchantment. Bombay Presidency’s Home Minister Morarji Desai was among the first ones to let his irritation show – something that taught Mário early on that lampooning political animals involved high risk. When he toned down the humour to appease the readers, cartooning quite paradoxically became a ‘serious business’. ‘Cartoonists are very serious people, and cartoons, no laughing matter,’[26] he quipped.

Finally, Mário stopped pursuing individual politicians; he began to see himself as a social caricaturist more than anything else. He is on record as saying, ‘I am not even a cartoonist; I draw… give me a pen and blank paper and I will draw. I just love to draw.’[27]

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[11] ‘Tale of Two Goans: Mario Miranda & Wendell Rodricks’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5FDLGApfATc&t=5s

[12] Cf. Fernando de Noronha, Momentos do meu passado (Goa: Third Millennium, 2002), p. 146.

[13] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[14] Cf. The Life of Mário (1949, 1950, 1951) ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous), in 2016, 2012 and 2011, respectively. Fátima Miranda Figueiredo reckons that her brother’s diary sketches total up to about 6,750 over a period of 18 years (1934-1951).

[15] He frequented the houses of his relatives, Judge António Miranda and Captain Adolfo Menezes, in Panjim, and Judge Eurico Santana da Silva, in Margão; and often stayed overnight with friends in their hostels.

[16] Nissim Ezekiel, ‘No escape if Mario is looking at you,’ in Mário de Miranda, ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous, 2005), p. 276.

[17] As told by Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021.

[18] Souvenir of the Silver Jubilee of the Loutulenses League (Goa: Imprensa Nacional do Estado da Índia, 1950). Curiously, in the chapter titled ‘The Rising Generation’, Mário figures as an Arts graduate, not as an Artist.

[19] Polly was from Bastorá; other hostelites, Joe Albuquerque and Paulo Miranda, from Loutulim. Cf. Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 14.

[20] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 15.

[21] Femina; Filmfare; The Evening News and The Economic Times.

[22] Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[23] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 24; Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.