ON: What does the ‘dream’ that you talk of in the Preface to your book mean to you and to our territory?

MU: Well, before I talk about my ‘dream’ I would like to clarify that when Seabra’s Civil Code [1867] was published, it did not have the chapters that I am going to stress on, as these were fruits of the Republic in 1910. Thus, the Portuguese Civil Code was a product of the Constitutional Monarchy; the law of Marriage, the law of Divorce and the law for the protection of children were specialties produced by the Republic. The Portuguese Civil Code did not have the concept of divorce; it simply dealt with the absolute separation of property.

ON: According to you, why didn’t Seabra introduce Divorce and, instead, dealt only with Separation? Was it through the influence of the Catholic Church?

MU: I don’t think so… The concept did not exist at the time. Divorce evolved much later.

ON: So, in 1910 all communities had access to the law of divorce…

MU: Yes; but the Church prohibited it, because one of the Articles states: those marrying through the Church are not entitled to divorce. This provision was later stuck down by our Courts because one could not discriminate between two communities.

ON: Well, the Civil Code would not discriminate between communities, yet it appears that the usages and customs only of certain communities were safeguarded in the Code….

MU: This was not about the usages and customs; this was a part of the law. Divorce (earlier it was Separation) was made part of the special legislation that came into force in 1910, after the Republic.

ON: Could you throw light on the usages and customs that were safeguarded?

MU: They were excluded in 1880, that is, before the Republic.

ON: Some examples of what was safeguarded…

MU: For example, one could marry at a predetermined age, which was reduced. Later, this law was extended to the Catholics also, because they pointed out that there was a tradition or custom to marry at an early age and that was permitted by the State.

ON: What was the age?

MU: The girl could marry at the age of fourteen.

ON: And the boy?

MU: At the age of sixteen.

ON: Is it true that members of the Hindu community were permitted to have more than one wife?

MU: There was a restriction. It required the consent of the earlier wife; and she had to be childless. Only then the second marriage was permitted; but this was struck down by the Portuguese law in the year 1952, on the grounds that polygamy had long been abolished.

TRANSLATING THE CODE

ON: Let’s talk a little about your translation: how long did it take you?

MU: Not long… just twenty years.

ON: Twenty years!

MU: Well, the total number of Articles of the Civil Code is 2538. There is also the Civil Procedure Code and miscellaneous legislation regarding the usages, customs and others which total up to more than 4000 Articles.

ON: So, yours is a translation of the whole of the Portuguese Civil Code…

MU: Not only of the Code but also of other laws that were published later…

ON: … which are connected to the Civil Code and to the Civil Procedure Code…

MU: Yes, the Civil Procedure Code, too, which has 1580 Articles. The reason for translating both the Codes is that the Civil Code alone is not sufficient; the Civil Code provides only the substantive aspect of law, but the enforcement or implementation is done through the Civil Procedure Code. Courts and others must follow the Civil Procedure Code, so the Codes are complementary.

The Code of Civil Procedure was repealed in the year 1939; the whole of it was the work of Prof. Alberto Reis and it was in force at the time of Liberation… At a conference at Simla, organized by advocates from the Indian Union, I had the opportunity to highlight the advantages of the Portuguese Civil Code and how it serves to decide cases much faster.

ON: But in Goa today only a part of the Portuguese Civil Code is in use, isn’t it?

MU: It was in use, but later it was gradually substituted by corresponding Indian laws.

ON: Which are those laws?

MU: For example, the Transfer of Property Act, Contract Act which formed an integral part of the Civil Code stood pro tanto altered.

ON: So, today, the Code is in use mainly regarding family laws…

MU: Yes, the law of marriage and divorce is unaltered. Fortunately, what existed here was repealed neither by the Union of India nor by the State government, except that every time an Indian law was introduced, the respective provision of the Civil Code was repealed. For example, the law of pre-emption… when an individual sells his right without giving preference to the co-owner. This is not provided for in the same way under the Indian law. The problem which arose was to see whether this provision of Portuguese law prevails or not. The courts said that it does prevail since a similar provision does not exist in the Indian Civil Code.

ON: In Portugal, is the same Civil Code still in use?

MU: No, it was changed entirely, in 1966, influenced by the Germanic theory… When Napoleon Bonaparte prepared a Code and appointed persons, he said that the Code had to use simple language, such that the public could easily read it. In contrast, the Germanic jurists said that eventually only the jurists should read the Code and not the public.

GOAN CONTRIBUTION

ON: This Code is a Portuguese legacy, but Goa is also connected to the Code, through a Goan – Luiz da Cunha Gonçalves – who has contributed a lot, thanks to his Treatise on Civil Law… Would you like to throw some light on this jurist?

MU: Of course! He writes in the Preface to the first volume: “More than sixty years have elapsed since the publication of our Civil Code, but whereas in the interim period many treatises and commentaries have been published in the main countries of Europe, especially in France and Italy, here in Portugal the scientific work in this branch of legal science has been scarce, fragmented, superficial, nothing to compare even with the treatises of French classics, nothing on a par with the modern treatises. It was therefore imperative that alongside our Civil Code, one of the best in the civilized world, an intensive and extensive work should emerge, of the kind that I have referred to. Nobody will fail to acknowledge it, and convinced that I will be rendering good service to the Portuguese legal science and the country, I will not hesitate to try and execute the work, presuming that I will be helped by ingenuity and art.”

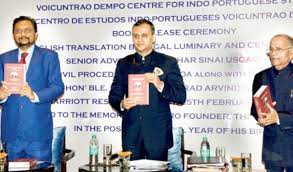

ON: It is evident from the host of names featuring in your book, right from the Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India, that your book and your translation of the Portuguese Civil Code did evoke a lot of interest…

MU: Yes, Justice Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Justice Couto and others have appreciated the translation. I can say that one who was really in favour of the Civil Code for Goa, Daman and Diu was Justice Chandrachud. He appreciated the law which existed, especially those three volumes, Marriage, divorce and Law for children, and he said thus: “The Uniform Civil Code remains today a distant world. In my view it would be a retrograde step if Goa, too, were to give up uniformity in its personal laws which it now possesses. Fortunately, as it appears now, the Portuguese followed a different policy in the matter of personal laws than the British. The Civil Code enacted by them covering inter alia family laws applied to all the communities living in this Union Territory except that the customs and usages of non-Christians were saved to a very limited extent. I am quite aware that the Uniform Civil Code of Goa, though it provides an ideal for the rest of the country, creates problems for the Union Territory of Goa itself. The special family laws operating in Goa which are different from those which operate in the rest of the country give rise to the peculiar inter-state conflicts of law. But this did not despair us because inter-state conflict of laws is one of the most perplexing aspects of American Federalism. The conflicts could be minimized by bringing the Portuguese Civil Code in line with some of the central statutes on the subject, at least in basic matters.”

ON: The Constitution of India states that the Civil Code ought to be introduced in India… You have been the Additional Solicitor-General of India. Do you think that the present social climate is favourable, and there have been efforts in that direction, or does the directive remain merely in the pages of the Constitution?

MU: Frankly speaking, till today no steps have been taken. It is an embarrassment to note that even after sixty years nothing has been done. However, the outcome of the Portuguese law was considered when there was a conference between Portugal and Goa, and judges and professors from different universities came here, and everybody spoke and appreciated the existence of the Civil Code. The conference took place when I was the Additional Solicitor-General of India.

ON: Oh! So, it was a very special event and an important step!

MU: After Independence or Liberation, as they call it, Parliament enacted a law, and it was mentioned that all the laws which are maintained are Indian laws. That was thus the first step for the maintenance of those laws – they could be repealed later, but fortunately till today the laws on marriage, divorce and [laws for] children have not been altered by the state. I have to say that there were efforts to discard it but what mattered was what the then Chief Justice of India Justice Chandrachud said: “It is heartening to find out that the dream of the Uniform Civil Code in the country finds its realization in the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu. How many outside are aware of this I cannot guess.”

DREAM

ON: Senhor Doutor, one last question: we have seen that the Civil Code is a legacy of the Portuguese. For your part, the translation of the Code is your legacy to the Indian Union.

MU: Yes, exactly. For as long as I live, it is my obligation to work to ensure that it shall continue.

ON: You were speaking of your dream: when would your dream be fulfilled?!

MU: My dream has three facets: first, the marriage must be compulsorily registered before the Civil Registrar, and this gives protection to the family. In the rest of India, this is done before the Hindu priest (Bhat), but it does not serve any purpose. Second, the regime of communion of properties, too, does not exist in the rest of India, and the third: reservation of the disposable share of legitimes is a system which maintains the balance, because half-share is reserved for the family and other half can be disposed of by the testator to whosoever he or she wants.

By introducing the legislation which is in force in Goa, Daman and Diu, justice can be done to all, and the interests of the children and wife can be protected. The concept of moiety which exists as per Portuguese law is recognized under section 5A of the Income Tax Act. This law is maintained by the Indian Union, and the payment of Income Tax by Goans is made, with due regard to the regime of communion of assets, as contemplated by the Portuguese Civil Code.

ON: But it seems that during the last two or three years there have been some problems in this respect.

MU: What problems?

ON: The Income Tax officers do not accept this concept of division of assets.

MU: It is not permissible to ignore the legislation; in fact, it is a violation of the law.

ON: They say that one cannot make a special provision only for Goa…

MU: They cannot be fail to comply with section 5A of the Income Tax Act. In fact, one of the Income Tax officers appreciated it and his subordinates did not want to accept it. He said thus: “If you do not accept, I will insist on making it applicable for the whole of India.”

ON: This brings us to our last question: the beautiful dream you have for India, when do you think it will come true?

MU: I do not know, but, frankly, I am trying to see that my dream is fulfilled. I will continue working till the end.

ON: Senhor Doutor, let me take leave of you, wishing you good health and many more years of work in this field. Thank you very much.

Acknowledgement:

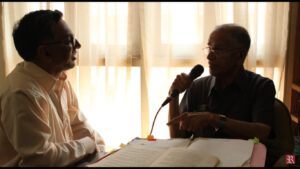

(1) For original chat in Portuguese, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i62XuPeTQuc (2) Translated by Tolentino António Colaço (3) Chat show photographs by Emmanuel de Noronha (4) First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 13, Nov-Dec 2021, https://casadegoaorg.files.wordpress.com/2022/01/revista-da-casa-de-goa-ii-serie-n13-novembro-dezembro-de-2021.pdf