Discovery of God

On Pentecost Sunday, we gladly encountered the Holy Spirit. Now it is only natural that the Most Holy Trinity should be in full view. This is the Solemnity we celebrate today.

It may come as a surprise to many that it is not the Incarnation, nor even the Resurrection, but the Holy Trinity that is Christianity’s central mystery, from which flow all the other mysteries of our faith. It is a mystery that has existed since the beginning of times but has unfolded only gradually.

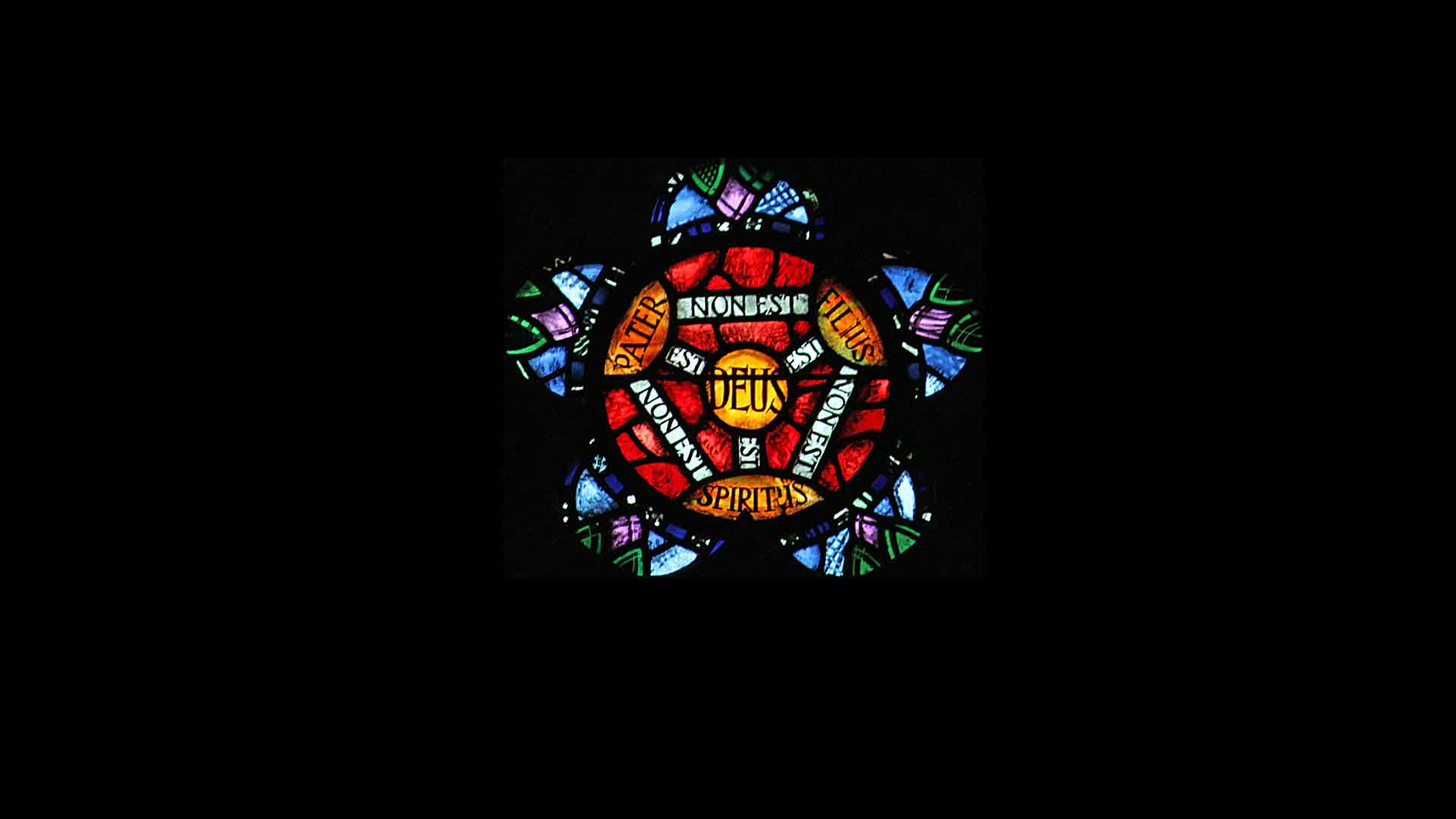

For instance, the Old Testament has references to the Three Persons but stops short of stating a Trinitarian doctrine. In the New Testament, Jesus pointed to His Father who loves us and desires our salvation; He presented Himself, the Son, as the Way, the Truth and the Life; and, before His departure from the world, He announced that the Holy Spirit would reside in our souls as a Guest. Yet, a doctrine of the Triune God was far from clear and remains to date just that: a mystery, a belief beyond our ability to understand unless God bares it to us.

None can deny, however, that the Trinity has been progressively revealed to humankind down the ages. It was not disclosed all at once, not only because of the finiteness of human minds, but because God patiently waits for us to exercise our freedom and come forward to learn about the intimate life of God. It is never an imposition; it is rather an invitation to establish personal ties with the three divine Persons.

That is what happened after Jesus. The early Christians felt it necessary to decode the Risen Lord’s instruction to make disciples of all nations, baptising them ‘in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit’. They also pondered St Paul’s blessing – ‘The grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all’ – now recited in the introductory rites of the Holy Mass. By and by, Biblical references to Father, Son and Spirit were put together as a cohesive doctrine.

In spite of all that welcome research, the Holy Trinity remains the most difficult theme of our faith. Today’s readings bear it out: they give only a glimpse, not a precise understanding of the mystery. In the First Reading (Prov 8:22-31), we hear Wisdom rather than God the Father speak. Anyway, God – who has defined Himself as ‘I am who I am’ – is Himself Wisdom, and is it not more graceful to be introduced by another than to introduce oneself? So, it is age-old Wisdom presenting the Eternal Father to us. Most importantly, we learn how He is not a distant God but One who delights in communicating with humankind.

In the Second Reading (Rom 5:1-5), St Paul talks of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, who gives us peace that no other can give. He also refers to the Father in whose glory we can hope to share by the merits of His Son’s Death. However, this supreme sacrifice has not eliminated human suffering from the face of the earth. The Apostle of the Gentiles urges us, therefore, to rejoice, for indeed, suffering produces endurance, character, and finally the hope of receiving a priceless grace: total communion with God.

In the Gospel (Jn 16:12-15), Jesus introduces to us the Holy Spirit, to whom He has entrusted the continuation of His mission till the end of times. The Son of God says, ‘I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now’; He leaves it to the Spirit of Truth to make things clear to those who yearn for the truth. And, whereas many things may forever remain a mystery, it behoves us to keep exploring that which has been revealed. At any rate, we who are created in the image and likeness of God have an infused knowledge and intuitively commune with the divine Family of Three.

What is the significance of today’s Solemnity? It reinforces our understanding of the Trinity. Our baptismal entry into this divine community deepens every time we gather around the Eucharistic Table. Today’s Liturgy is set to make us passionate about discovering our God. Our God is not a solitary Being lost in the dark and infinite space but a communitarian God of life and love, a model for the human family.

What is the significance of today’s Solemnity? It reinforces our understanding of the Trinity. Our baptismal entry into this divine community deepens every time we gather around the Eucharistic Table. Today’s Liturgy is set to make us passionate about discovering our God. Our God is not a solitary Being lost in the dark and infinite space but a communitarian God of life and love, a model for the human family.

No minds however great and no words however eloquent will adequately express this most complex of all Christian concepts and doctrines. The most popular story illustrating this fact is taken from thirteenth century Italian Dominican Jacobus de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea. Accordingly, St Augustine was walking by the shore, meditating on the problem of how God could be three Persons all at once, when he notices a little child scooping water from the sea into a small hole he had dug in the sand. When asked what he was doing, the child answered: ‘I’m emptying the sea into this hole.’ ‘What! The sea is too large for the hole,’ retorted Augustine. And pat came the child’s reply: ‘Indeed. But it is easier for me to empty the sea into this hole than it is for you to grasp the mystery of the Holy Trinity.’

At the time, St Augustine was working on De Trinitate which, quite suggestively, he was unable to complete to his heart’s content. But even though his treatise on the inscrutable mystery remained unfinished he did not give up his discovery of our many-splendored G od. Shouldn’t we take a leaf out of his book?