Goa’s culture has long been in the public eye. It has drawn the attention of travellers, academics and statesmen. Some have been quite the culture vultures, lapping up just about everything; others have woven theories, looking at parts to the detriment of the whole; and yet others have just milked the culture dry. The culture-scape is thus fraught with risks. The real work lies in valuing this composite culture, hearing the voice of the local stakeholder, and not letting the golden goose die.

Goa’s culture has long been in the public eye. It has drawn the attention of travellers, academics and statesmen. Some have been quite the culture vultures, lapping up just about everything; others have woven theories, looking at parts to the detriment of the whole; and yet others have just milked the culture dry. The culture-scape is thus fraught with risks. The real work lies in valuing this composite culture, hearing the voice of the local stakeholder, and not letting the golden goose die.

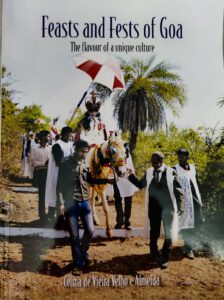

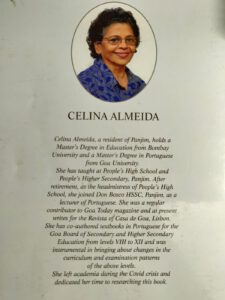

Celina de Vieira Velho e Almeida in Feasts and Fests of Goa: The Flavour of a Unique Culture has claimed her voice. She has documented many of her land’s cultural expressions, based on field work and published material. Her translating sources in Portuguese, updating ethnographic data with contemporary testimonies, and sharing backstories has added value. Missing, however, is a critical introductory essay, which could have provided an apt backdrop to Goa’s culture graph.

The book’s alliterative title could be misread as repetitious. Contextually, however, we may distinguish between a ‘feast’, as a day commemorating a saint or a sacred mystery, and a ‘fest’, as a broad-based celebration. Besides, ‘fest’ in the local Konkani is a corruption of the Portuguese festa, which has both religious and secular connotations. No doubt, most religious feasts in the Christian liturgical calendar are quiet, spiritual affairs; so, not all feasts are fests, even if merriment be the ‘in’ thing in a modern, desacralized setting.

Each of the book’s seventeen chapters maps a feast or a fest. The feast of the Epiphany (at Verem, Chandor, Cuelim) and that of Our Lady of Safe Port (Santa Inez, Panjim) are wholly religious events. The latter is the book’s sole city-based feast and happens at the parish level; the former, with all the countryside fanfare, has acquired a folkloric character. Maybe folksier are the chapel feasts at Pilerne, Siridão, Nerul, and the church feasts at Talaulim and Curtorim: their fairly recent, multicultural dimension has turned them into veritable fests.

Pilerne’s feast of Candelaria is now better known as Kottianchem (Coconut Shell) Fest; Siridão’s feast of Jesus of Nazareth, as Pejechem (Rice Gruel) Fest; and Nerul’s feast of St Anthony is Tisreanchem (Clam) Fest. Ironically, of Curtorim’s Kelleam (Banana) Fest, coinciding with the parish feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, only the name remains; the fruit is conspicuous by its absence. In striking contrast, at Touxeanchem (Cucumber) Fest held at Talaulim’s Santana parish church, one of the finest specimens of Indian Baroque architecture, touxem is a votive offering. Childless couples and matrimonial hopefuls come and say a prayer to St Anne, in Portuguese.

Cultural metamorphosis is perhaps best exemplified by São João, generally mispronounced as Sanjanv. Calling it ‘a Portuguese folk festival’ may suggest that it was transplanted to Goa root and branch, but that was not the case. The life of St John the Baptist so fired the popular imagination that the liturgical feast took on a life of its own, both in Portugal and in Goa. The same could be said of the carnivalesque Potekaranchem Fest, or so-called ‘Shabby’ Festival, held three days before Ash Wednesday, on Divar Island.

Celina Almeida traces the origins of pre-Christian festivals too, thus covering Goa’s Hindu and, perhaps underexplored, Muslim past. She labels Mussol Khel [Pestle Dance] ‘a unique celebration of Chandor Kott’s [fort area] history in dance form.’ The rice pounding festival, symbolic of thrashing the enemy, which formerly took off from a temple, now starts with prayers at a chapel. This, however, is not the only festival to have absorbed Christian elements. Syncretism is the leitmotif of Zagor, a night vigil conducted to placate the gods and ancestral spirits; typified here by Siridão’s Gauda tribe, some of whose Christian members relapsed into Hinduism decades ago.

Proud of the peaceful coexistence of Goa’s many communities, the author makes no value judgements on religious orthodoxy, or the lack of it. She says that Cuncolim’s Sontrio (Umbrella Festival) rooted in the worship of Hindu goddess Shantadurga ‘appears to hold sway over both the major communities in the village, viz. the Catholics and the Hindus.’ Similarly, she considers village Surla-Tar’s Shigmo festival ‘a beacon of Hindu-Muslim communal harmony in Goa.’ In this springtime festival, a dance troupe from Siddheshwar temple visits a dargah and a mosque; Hindus and Muslims exchange gifts, and a maulvi participates in a Hindu ceremony.

While the author urges fellow Goans to make culture relevant to future generations, she lashes out at the authorities for their venality, rampant in the tourism and environmental sectors. She hails Chikal Kalo, organised in the predominantly Hindu village of Marcela, as the world’s only mud festival with religious underpinnings. She acclaims Curtorim’s Handi (Dyke) Fest as ‘a celebration of their contribution to the preservation of water’. The long, eco-friendly tradition of this largely Christian village is evident from its five natural reservoirs and reputation as Saxtticho Koddo (Granary of Salcete).

Two chapters of the book unwittingly pay tribute to the family as an institution. Panjim-based Mhamai Kamat family’s Anant Chaturdashi, centred on the story of a rare conch of religious import, illustrates how one household can animate an entire community. Further, in ‘Ladainhas of Goa’, the author reminisces about the litanies held at her maternal grandparents’ home in Utorda. In fact, even at wayside crosses, where multilingual prayer and singing is a given – and so are those boiled grams garnished with grated coconut washed down by feni or light beverages – litanies could easily be a feast or a fest!

Feasts and Fests of Goa, replete with information of interest to both local and diasporic Goans; excellent colour photography, map, glossary and bibliography, lets the reader experience ‘the flavour of a unique culture’. The book features celebrations held in a little over fifty per cent of Goa’s talukas, leaving ample room for a sequel. The author exudes love for the land and its culture just as naturally as our people did in former times. Hopefully, this will inspire the rest of us to be vocal – and, more importantly, the powers-that-be to take the right steps – in this fast-paced, globalised world, lest our culture be relegated to just between the covers.

FEASTS AND FESTS OF GOA: THE FLAVOUR OF A UNIQUE CULTURE

FEASTS AND FESTS OF GOA: THE FLAVOUR OF A UNIQUE CULTURE

Celina de Vieira Velho e Almeida

Panjim: Self-published, 2023.

Pp 105. PB. Rs 1200/-

Excellent presentation of the book. Traditions are not only important for what they symbolize, their conservation is also important for the future of new generations. A way to keep alive the identity of each town or nation.

Kudos to the author for compiling a record of Goem’s fests, may they continue to revive spirits and hearts for decades to come. The food and feni are just bonuses, future generations will benefit immensely by being around sacred spots, sanctified by centuries of scripture, prayer and chanting — instead of going elsewhere, like moths to a neon flame.