Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 7

Part 7 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata – VII", by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

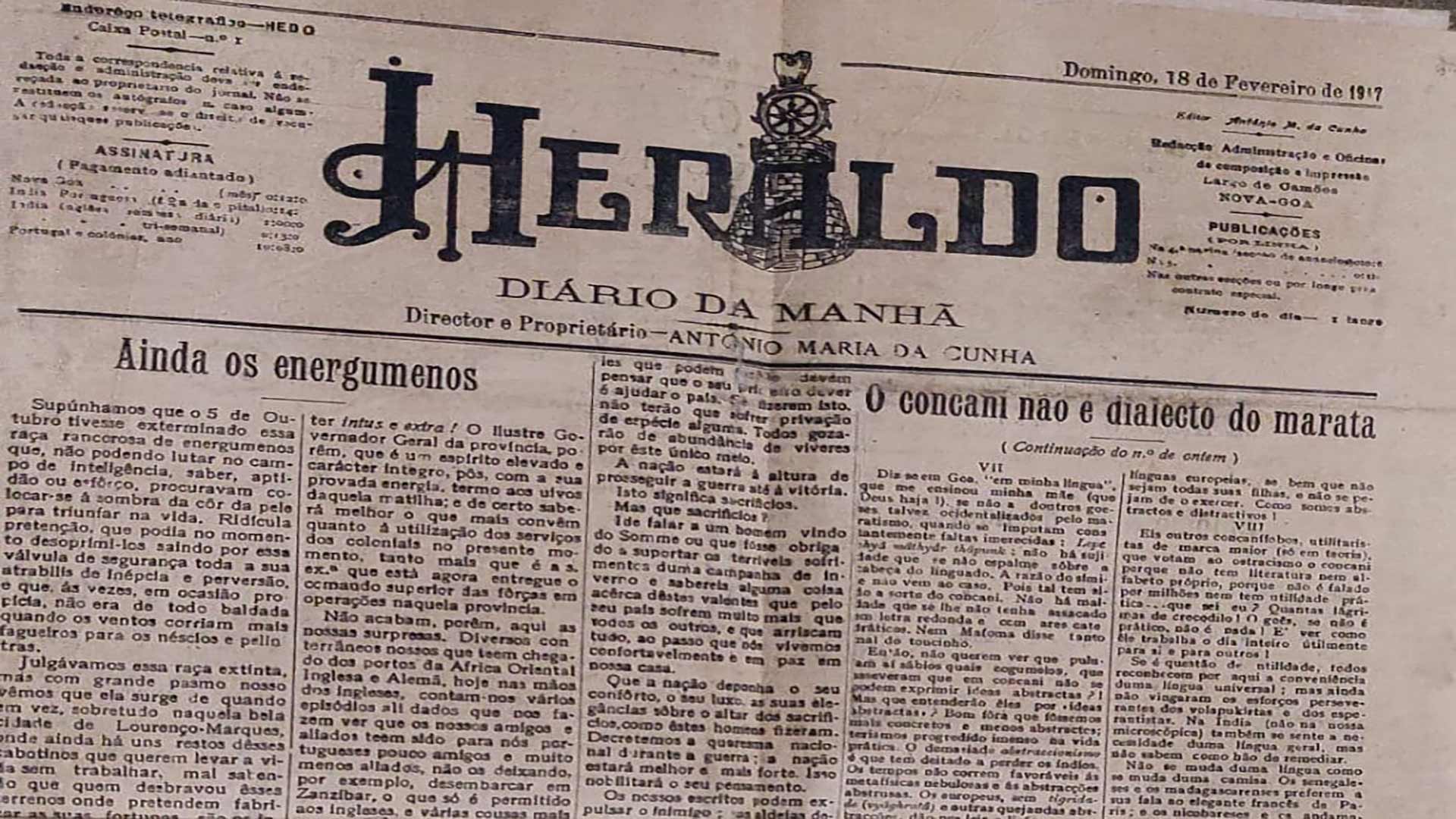

Published in Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2575, 18 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha and published in

Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 29, July-August 2024, pp 29-31

Lepechyâ mâthyâr thâpunk: there is no dirt that does not spread over the flounder’s head. This is said in Goa, ‘in my language’, which my mother (may she rest in peace!) has taught me, even it is not that of other Goans perhaps westernised by Marathism; when unwarranted faults are constantly imputed. The reason for the simile is beside the point. For such has been the fate of Konkani. No evil has been left unattributed to it in print and with a professorial air. Not even Mohamed has so viciously bad-mouthed bacon.

Do you not see, then, that the place is swarming mushroom-like with learned men, who state that in Konkani one cannot express abstract ideas? But what do they mean by ‘abstract ideas’? If only we could use more of concrete rather than abstract language; we would have made much progress in practical life. Too much of abstractionism is what is destroying the Indians. The present times are not conducive to nebulous metaphysics and abstruse abstractions. The Europeans, without tigritude (vyaghratā) and other such abstractions, provide us with laws and lessons.

But is it true that the spoken language of the Goan Christians has not a word to denote abstract ideas? And the current and past preachings, do they only deal with concrete things about the cult of linga, yoni, xaxti, Betalla, king cobra? And so many manuals and devotionals, besides books and newspapers that are published, especially in Bombay, don't they contain abstract ideas?

And the Christian catechism? Surely, that's not Marathi. A philological authority has already stated that pottárth, alpabhojan, sadaiv, and other such terms do not exist in Marathi and Sanskrit or do not have the connotations that we assign them. Now, the catechism has hundreds of words like those to designate dogmas and mysteries, virtues and vices, gifts and fruits of the Holy Spirit, dispositions for the sacraments, etc. Are they all concrete words?

Hence, I would have liked to be in Goa and at a public contest see who has abstract ideas, whether a Christian lad with just the knowledge of the Konkani catechism, or a Hindu lad, of the same age, with wide knowledge of Marathi. I do not for a moment hesitate to say that the Christian would carry off the palm.

The reason is obvious to those who know what generally professed Hinduism is. It is in essence more elastic than rubber. That is why it does not have a catechism, a code of doctrines and precepts. Ask a cultured Hindu to state in a few words what he should believe and practice in accordance with his religion, and see the result. It would not be the same with a Buddhist or a Jain. An orthodox Hindu is he who accepts the Vedas in theory, even if he has not seen them, and caste distinctions in practice, even if he cannot explain himself. The rest hardly matters. Philosophers and theosophists have mercilessly rattled the Vedas with their doctrines, but did not openly repudiate them. And that was enough.

If, to express abstract ideas, the Marathists constantly turn to Sanskrit vocabulary, does not Konkani have the same right? Or is Sanskrit the monopoly of the Bhonsles, and no other can touch it? European languages have equal right at least to Greek and Latin, even though they are not all their children; and they do not hesitate to exercise it. How abstract and distracting we can get!