BOOK REVIEW | Óscar de Noronha

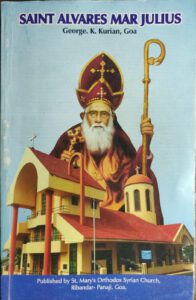

Saint Alvares Mar Julius, by George K. Kurian. Goa: St Mary’s Orthodox Syrian Church, 2013. Pp 168. ₹ 80.

It does not seem like there is anyone today who has known him personally, for he died over a century ago. Those who did remember him, in the years gone by, usually spoke in hushed voices, given his anti-establishment posture; but even his severest critic would admit that he had a heartbeat for the voiceless in Goan society.

Born António Francisco Xavier Álvares (Verna, 29/4/1836), he studied at Rachol Seminary and was ordained a priest in Bombay (the episcopal chair in Goa was vacant). On his return, he set up a charitable society to rehabilitate beggars (some of whom lodged with him in his rented apartment in Panjim) and a church-aided school. Quick to reach out, especially when deadly epidemics raged in the capital, he once personally saved labourers trapped in a landslide triggered by hill cutting.

The focus of George K. Kurian’s book (Figure 1), however, is the unprecedented entry of that Roman Catholic priest into the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. Until his early public years, Fr Álvares was a conservative and loyalist to the point of defending Portugal’s Padroado rights; what, then, was really the tipping point?

Kurian points a finger at Archbishop António Sebastião Valente’s objections to the tenor of Fr Álvares’s writings in the local press (pp 53, 81); but alas, he stops short of identifying the genesis of his unease, which predated Valente’s arrival in 1882. Over a period of 18 years (1877-1895), the cash-strapped Fr Álvares came to be associated with a number of periodicals (A Cruz; A Verdade; O Progresso de Goa; The Times of Goa and Brado Indiano), in different capacities. Whether or not his politically minded associates and/or funders rode piggyback is a moot point.

Similarly, the author states that the Catholic Church in Goa excommunicated Fr Álvares (pp 75, 158), but provides no proof in support of the claim. It was more likely an excommunication that the priest incurred automatically (latae sententiae), as per the Code of Canon Law, as a result of his entry into the Malankara church in 1887.

At any rate, the purpose of an excommunication is to call a person to change behaviour, repent, and return to full communion. But none of that happened. Instead, in 1888, Fr Álvares went on to form the Independent Catholic Mission of Brahmavar, Karnataka. Was this in response to the Padroado-Propaganda Fide imbroglio?

The rest is history. In 1889, Mar Dionysius, who headed the Malankara church, appointed Fr Álvares to a specially created episcopal post of Metropolitan of Goa, India (excluding Malabar) and Ceylon. Titled ‘Mar Julius’, he still said Mass in Latin (his Syriac and Malayalam were not up to par), catering to the Indian Orthodox Church’s Roman Catholic lay entrants, who were permitted ‘a separate rite and liturgy’ (p. 62). He highlighted the antiquity and authenticity of Antioch vis-à-vis Rome (p. 91) and criticised Western cultural practices in vogue in Goa as against the preferential status that Indian traditions were given in Malabar (p. 54).

In the period 1887-1911, Fr Álvares divided his time between Ceylon, Kerala, Brahmavar and Goa (pp 63, 71). In 1890, the Goa police booked him for unauthorised use of ecclesiastical vestments (p. 111), but the court, on taking cognisance of his episcopal status, acquitted him. On a later visit to his native land, he championed the use of indigenous products (‘a forerunner of the great Swadeshi Movement’, p. 95) and found himself in a spot for denouncing the powers-that-be. He was ultimately charged with sedition and arrested for inciting the Maratha sepoys and Ranes through his writings (p. 113). The court exonerated him (which speaks volumes about the justice delivery system), but Fr Álvares fled yet again, fearing reprisals.

In 1911, Fr Álvares was at the receiving end of a feud between the Patriarch of Antioch and Mar Dionysius (p. 87). It was as if life had come full circle when, excommunicated for siding with the latter, he relocated to Goa and stayed in the same old, ground-floor apartment off Ourém Street. The big difference now was that the Republicans were in power in Portuguese India; but was that why the Malankara archbishop left his domain in Karnataka?

It would be interesting to know what Fr Álvares thought of that secular (read anticlerical) regime, other than that he was left in peace. This time around, he set up an English-medium school and made a plea for primary education in Konkani (p. 78). While in the past he had very relevantly published booklets on the treatment of cholera, presently he advocated large-scale cultivation of manioc as a solution to Goa’s food crisis. Finally, in the evening of his life, devoting himself entirely to charity work, he actually went out with a begging bowl.

Not surprisingly, the longest of the book’s 18 chapters is titled ‘A True Missionary’, which speaks about Fr Álvares’ apostolic work, his associates and the expansion of the Malankara church in India and abroad. The last few chapters describe the final days of this ‘martyr and saint’; his funeral; long-standing friendships; tomb at St. Inez Cemetery; and the formation and work of the Orthodox Church in Goa. Kurian notes that the Roman Catholic Church’s efforts to win Fr Álvares back were in vain. The dying priest insisted that if not the Orthodox Church, his friends alone would bury him (p. 118). He died at Ribandar public hospital (23/9/1923).

The topic of retired bureaucrat George K. Kurian’s self-published volume is intriguing no doubt, but more rigorous editing would certainly enhance clarity and coherence. It is a pity that instances of repetition, typos and grammatical errors detract from the overall reading experience. The book was originally written in Malayalam and is a work of love. The author even took the trouble to include a family tree of the Álvares, besides photographs of the priest and pages of Diário da Noite and O Heraldo, two dailies that covered the funeral and aftermath. All in all, the book helps get a glimpse of the enigmatic figure of Padre Álvares/Mar Julius.

A very intriguing matter. Why would this priest take this extreme step? Hope your research will provide some clarity.

Excellent review, Oscar. Padre Álvares seems to be an intriguing character. Sadly, (as even today) the Church establishment did not find a way to channelise his talent of reaching out to the poor & the marginalised, which should have been at the core of Christian teaching & practice. Thanks for sharing.

Fascinating personality, Fr. Álvares Mar Julius. Thanks to George K. Kurian for the publication of the book and to you Oscar, for the review that gives us a glimpse of this singular compatriot.