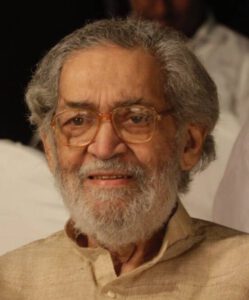

The recent passing of Gerson da Cunha in Mumbai, a man of many parts, took me back to when his namesake granduncle José Gerson da Cunha wore many hats. The Origin of Bombay was just one of the many books the latter authored. It triggered my thoughts on the long presence of Goans in the metropolis and their contribution to its growth.

Goans had sporadic dealings with Mumbai, and the nearby towns of Chaul and Bassein for centuries. But it was not before the nineteenth century that they began to see Mumbai as a second home. It all started when some Goans in the employ of the British army stationed in Portuguese India (1799-1813, ostensibly to ward off an attack from the French), went along to British India as cooks, musicians, tailors, and so on. Thanks to their qualities of head and heart, a few even joined the Peshwa army and settled thereabouts, or moved to Mumbai, a city in the making.

Mumbai beckoned. It was an upcoming centre of education, trade and industry. Elphinstone College and Grant Medical College had seen many Goans even before the University was set up in 1857 and the J. J. School of Art soon thereafter. At that time, the textile mills, the tramway companies and the printing presses were employment hubs. Desperate to earn a livelihood, Goans travelled by patamaris or on riding-animals; much later, the metre-gauge railway line and the coastal steamer service emerged as express corridors to that bustling port city.

In her book Goan Pioneers in Bombay, Teresa Albuquerque states that ‘except for the lower classes pressed by abject poverty, Hindus generally refrained from migration to Mumbai until the middle of the nineteenth century.’ However, their population eventually grew ten times larger than that of the Goan Christians; they merged easily into the mainstream, while Christians, better attuned to the city’s western cultural ethos, including use of the Roman script, grabbed every opportunity to rise.

Life in an alien land never comes easy. Goan Christians were fortunate to escape the shanties, thanks to lodging and boarding available at their respective village kudds (clubs) scattered across the city. There they shared their joys and sorrows; and at times they drowned these at a tavern or at the tiatr, a new art form they had developed collectively. The more religiously inclined found solace at a wayside cross, chapel or church, while the more cerebral ones vented themselves through the newspaper columns. At any rate, every Goan worth his salt awaited a wedding, a church feast or a zatra to draw them back to home and hearth. Joseph Furtado’s nostalgic poetry of exile says it all:

I now live in the city

But my heart’s in the country;

In the city I languish,

And a wild thorn or tree,

If I happen to see,

It thrills me with anguish.

By and large, Goans were not ghettoised. By their natural ability to be all things to all people they secured work as seamen, cooks, butlers, ayahs, bakers, confectioners, tailors, musicians, coach builders, jewellers, millworkers and undertakers. According to Albuquerque, ‘while most of the Goan emigrants in Mumbai were miserably poor and struggling to survive, there were also a few – very few – who could have been considered fabulous tycoons’, most of whom, sadly, are ‘not remembered for works of philanthropy.’ There were also intellectual stalwarts, eminent physicians, social workers, sportsmen, entertainers, and many notables who promoted education and culture (including the University and the Royal Asiatic Society), engaged in welfare services, and set up periodicals in Konkani, Marathi, English and Portuguese.

A curious feature of Mumbai is that, until the nineteenth century, Portuguese was almost a lingua franca amid the Christian community, both Goan and East Indian. Certain churches were under the jurisdiction of the Portuguese Padroado. Until 1928, records were maintained and ceremonies conducted in that language by priests that churches in Dhobitalao, Cavel, Dabul, Byculla, Mazagaon, Dadar, Mahim, Bandra, Vile Parle and Kalina largely drew from Goa. In The Making of Mumbai, Benny Aguiar concludes his narrative about the metropolis and its Catholic past with a Goan, Valerian Gracias’ appointment as archbishop of Mumbai in 1950.

By mid-twentieth century, Goans were well established in Mumbai. There was probably no sector without their presence. Oncologist Ernest Borges, gynaecologist V.N. Shirodkar, professors Armando Menezes, Manuel Colaço and C.D. Pinto, educationist Aloysius Soares, journalist Frank Moraes, singers Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosale and Kishori Amonkar, cartoonist Mário Miranda, painter F.N. Souza, poet Dom Moraes, top cop Julio Ribeiro, scientist Anil Kakodkar, architects Charles Correa and Edgar Ribeiro, engineer Manuel Menezes, beauty queen Reita Faria, historians John Correia Afonso and George Moraes, ad gurus Frank Simões and brothers Gerson and Sylvester da Cunha, artistes Micky Correa, Chris Perry, Lorna, Souza Ferrão, Braz Gonsalves and Anthony Gonsalves, to name but a few, were household names.

‘Bomboicar’ or ‘Bombay Goans’ – the hoi-polloi more than the gentry – favoured their families with remittances that helped change the face of the homeland. Nonetheless, back in the Portuguese era, they were by and large looked down upon. There was perhaps a subtle animosity between the cash-strapped homegrown Goans and their anglicised counterparts. These latter indicated that they belonged to a modern industrial-urban society while their country cousins languished in sossegado rural environs. It is quite likely that this love-hate relationship stemmed from long-standing Anglo-Portuguese colonial complexes.

All in all, it has been a win-win situation. In his book The Portuguese Presence in India: Latter-day Thorns amidst Tranquillities, John Menezes talks about “the Goan voice, once vibrant and contributing richly to the pluralistic fabric of the city”. Today the Goan presence in Mumbai is so diffused that individual roles are more difficult to pin point. But they love the city and contribute greatly to its civic life, like da Cunha did. The Goa-Mumbai relationship will be alive and kicking as long as those Goans keep thinking of the green, green grass of home.

First published in The Goan Review, August 2022 https://online.fliphtml5.com/cmlao/gqia/?1660569685081

Banner: Gateway of India, https://pixahive.com/photo/gateway-of-india-mumbai/