CBCI and the Apostles

Last Sunday we witnessed the Resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, by far the greatest event of heaven and earth. We celebrate it every year, and it has perhaps become clichéd. But then, we would do well to remember that the Resurrection is central to our faith. What happened to Jesus is a promise to every Christian; by His resurrection we know that we, and all who have gone before us, will be raised from the dead.

The earth-shattering happening resounded hugely in Jerusalem. To begin with, Peter and John, Mary of Magdala and other women of Galilee encountered the Resurrected Lord on Easter morning; and that evening, He appeared to two on their road to the hamlet of Emmaus. And while some of the disciples failed to accept their Master’s Resurrection as true, Jesus stood in their midst, saying, ‘Peace be upon you.’ After mildly reproaching them for their scepticism, He went on to reassure and convey to them His power.

As a result, when asked by the Sanhedrin, ‘By what power or by what name did you do this [healing]?’, Peter replied boldly: ‘… by the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, whom you crucified, whom God raised from the dead…’ The priests had nothing to say in opposition to the healings, but warned the Apostles to speak no more to any one or teach in Jesus’ name. Peter and John retorted: ‘Whether it is right in the sight of God to listen to you rather than to God, you must judge; for we cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard.’

In short, that is what transpired in the first week of Our Lord’s Resurrection; that was the fire with which the Apostles spoke, convinced of Christ’s divinity. Contrast it with the recent whimper of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI), purportedly to help address ‘emerging challenges due to the current socio-cultural, religious, and political situation’[1] in the country. The CBCI is the apex decision-making body representing the Catholic community in India; but do their decisions inspire and embolden the Catholic fold, or do they, instead, gaslight and dishearten the community?

-o-o-o-

After the Easter week, during which we read from the Acts of the Apostles, considered the second part of St Luke’s Gospel and makes up the First Reading (4: 32-35), we have yet another text that relates the apostolic labours and first steps taken by the Christian community. The Church considers the Acts a precious guide and exemplary stimulus for the life of Christians: it portrays how they went from listening to the Word to developing the faith; from Baptism to solidarity; from persecution to martyrdom.

‘The company of believers were one of heart and soul,’ says the physician-author Luke. Thus enthused, they found no point in owning things; they held them in common. This practice, however, was never obligatory but purely voluntary; it does not favour the socialist ideal or go against the concept of private holdings. The believers’ focus was on testifying to the Resurrection. And great was the grace among them; with all receiving due attention, there was no needy person among them. They worried not about their life, about what they would eat or drink, or about their body and what they would wear. (Cf. Mt 6: 25)

Truly, our life is more than food, our body more than clothing. What’s more, our Resurrected Lord gives us life, and life in abundance. We should not be concerned about rejection, for the stone which the builders rejected finally became the cornerstone. Such is the work of the Lord, a marvel in our eyes, says the Psalm. Hence, dear CBCI, ‘when they hand you over, do not worry about how you are to speak or what you are to say; for what you are to say will be given to you at that time.’ (Mt 10: 19)

In the Second Reading (1 Jn 5: 1-6), St John makes a rare appearance[2] through his epistle. He assures his community, possibly based in proconsular Asia[3], that God’s commandments are ‘not burdensome. For whatever is born of God overcomes the world; and this is the victory that overcomes the world, our faith. Who is it that overcomes the world but he who believes that Jesus is the Son of God?’ This is not a simple text; here, the Beloved Disciple of Christ counters the Gnostics who denied the Incarnation and Death of the Son of God. Hence, the Epistler affirms that ‘this is He who came by water and blood, JESUS CHRIST, not with the water only but with the water and the blood.’ That is to say, God did not abandon Jesus before his Passion and Death.

If it be natural for one to fear bloodshed, is it not supernatural that martyrs have had the courage to shed their own? The Gospel (Jn 20: 19-31) tells us how on the evening of the Resurrection, the doors being shut where the disciples were, for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them, saying, ‘Peace be with you.’ He had returned to fulfil His promise at the Last Supper. He now commanded them to go out into the world and proclaim the Good News of Salvation; he also imparted them the sublime power to forgive sins (Sacrament of Penance). Although among them was one who doubted – Thomas – in a bit he too was touched and transformed by the Lord. And then, he touched India and transformed us.

May the CBCI, you and me be inspired by the example of St Thomas the Apostle of India, who is wrongly labelled ‘Doubting Thomas’. He sent forth the highest profession of faith in Christ’s divinity: ‘My Lord and my God!’ Let us, then, with our hearts set on fire, have recourse to him who once doubted, but not for long, and ever after acted strong. And on this Feast day of Divine Mercy, meant to be a special refuge and shelter for the consolation of souls, may we grow in the love of God and merit His mercy always.

-o-o-o-

[2] ‘The First Letter of John is the ONLY biblical book that is included in its entirety in the Lectionary for Mass! It is scheduled to be read every year on the weekdays of the Christmas Season, although not all of it is read in any particular year, depending on which days of the week Christmas and Epiphany are celebrated. On Sundays and Major Feasts, only about one third of 1 John is read (mostly on the Sundays of Easter in Year B). Selections from 1 John are also recommended or optional for several Saints Days and various other Masses. In contrast, the Second and Third Letters of John are never read on Sundays and never recommended for special Masses, but only one short reading from each letter is scheduled for a weekday Mass every two years.’ https://rb.gy/bwjmxd

[3] The Roman province of Asia, whose most prominent cities were Ephesus, Sardis, Pergamon and Aphrodisias (modern names: Selcuk; Sart; Pergamos; Geira, all in Turkey). A proconsul was in charge of the Asian province.

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 5A

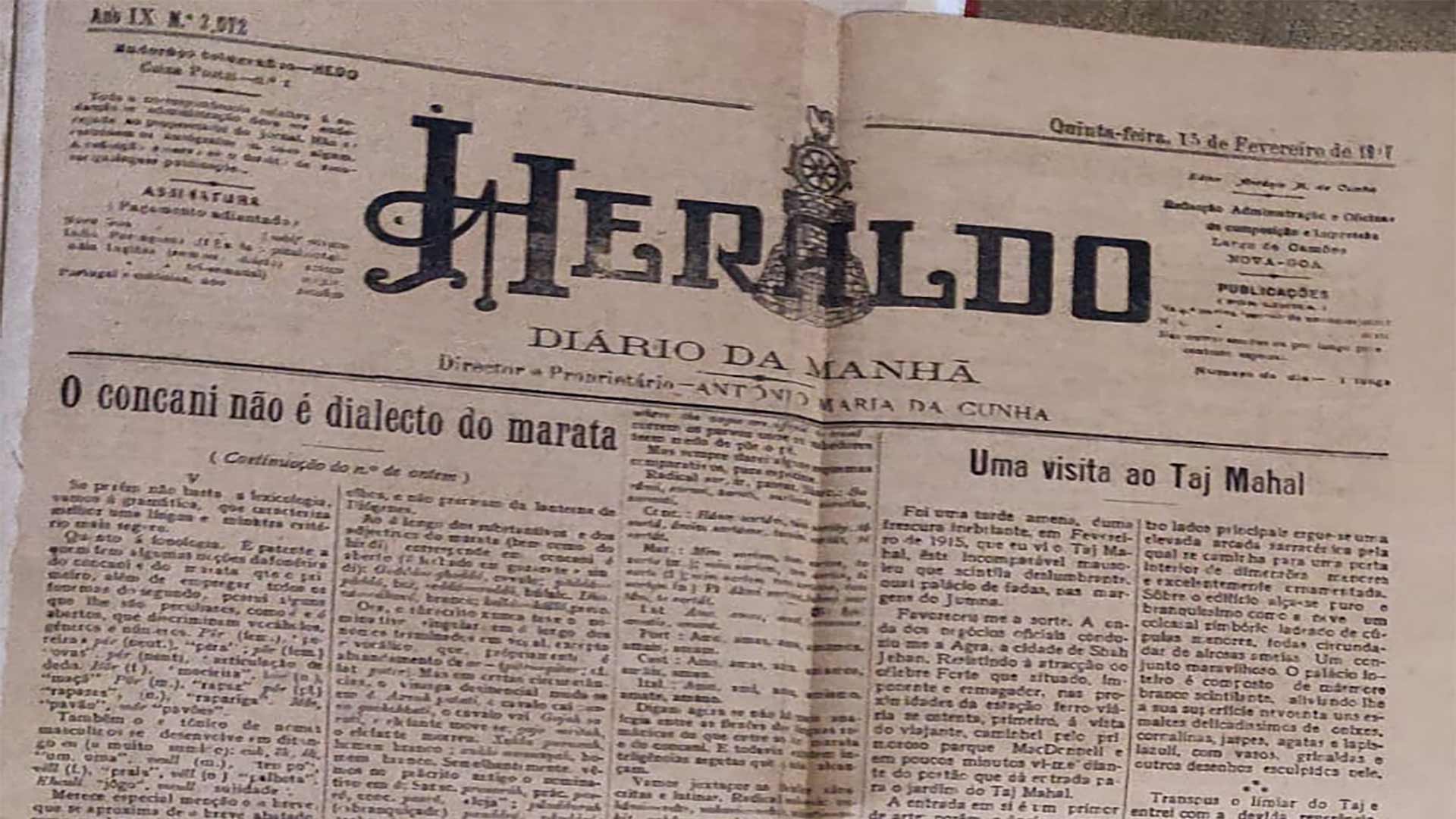

Part 5[A] of “O concani não é dialecto do marata”, by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado,

in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2572, 15 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

If, however, lexicology does not suffice, let us look at grammar, which better characterises a language and provides a safer criterion.

As regards phonology, it is obvious to whoever has some notion of Konkani and Marathi phonetics that the former, besides employing all the phonemes of the latter, has some unique ones, such as open é and ó, which distinguish words, genders and numbers. Pêr (fem.), guava tree, and pér (neut.), guava; pêr (fem.), roe, pér (neut.), finger joint. Bôr (f.), jujube tree, bór (n.), jujube. Pôr (m.), lad, pór (pl.), lads, (n.), girl. Môr, peacock, mór, peacocks.

The tonic e of masculine nouns also develops into diphthong eu (very faint u): euk, êk, ék, one, one, veull (m.), time, vêll (f.), beach, véll (n.), pick, kheull, game, meull, dirt.

The short a deserves special mention; it is close to the muffled and short o, as in Bengali, or better, as in the English u in but, cut.

It also has another notable peculiarity: that of being, like the open and closed o, contingent on the genders. The a of bhirandd, mangosteen tree, and the a of bhirandd, mangosteen, are not pronounced identically, except perhaps by a child in diapers. Also compare the second a of kharadd (f.), shavings, with that of kharadd (n.), bald head; that of karadd (f.), dryness of tongue, with that of karadd (n.), grass. Those who fail to understand this may be capable of speaking the Bunda language, which does not require great expertise, but they certainly do not understand the phonics techniques of Konkani. It is said that honey is not meant for the ass’s mouth.

Similar to the pre-consonantic tonic e of masculine nouns, the long á of certain feminine nouns develops into a regressive diphthong eá (or yá) with muffled e: sattyá = Sansk. sattá, authority. Tarhyá = Mar. tarhá, from the Arabic tarhá, type, manner.

The ch and j, when not preceding e and i, always sound ts (or tç) and z, without etymological restrictions; which is not the case with Marathi. Sansk. chal = tsal, go; char = tsar, folder; chakra = tsak, wheel; Râjâ = rázá, king; jana = zann, person; jati = zát, caste. People observe the logical coherence instinctively and send the etymologists packing. But in our eccentric Goa there are philological heavyweights armed with a ferule: they disregard such a clear truth! Or else, they would not be pinchbeck scholars nor would they be acclaimed by puppets.

Furthermore, the initial h and the h of aspirated consonants is not as sonorous as in Marathi, and many of the Marathi cacuminal initials correspond to the respective dentals in Konkani.

Can all these peculiarities be borne out by the evolutionary process or, if unscientific detractors so wish, by later corruption? And how is it that identical phenomena are unheard of in other Marathi areas? And will not at least such elements be useful to establish the autonomy of a language?

With regard to morphology: if there was anyone who, comparing the declensions and conjugations of Konkani and Marathi, has found complete uniformity, he was blind in spirit. The multiple and grave discrepancies are, as the English say, glaring; they stand out and can do without the lantern of Diogenes.

The long á of the nouns and adjectives in Marathi (as well as Hindi) corresponds in Konkani to open ó (closed ô in Gujarati and Sindhi). Goddá = ghoddó, horse; pâddá = pâddó, bull; reddá = reddó, buffalo; dhava = dhavó, white; kallá = kâlló, black.

Now, Sanskrit has never had the nominative singular in long â of the nouns ending in a vowel, except for vocalic r, which, really speaking, is a softening of ar (pitr = pitar; cf. Lat. pater). But under certain circumstances, the desinential visarga changes to ô. Axvah patati, the horse falls; axvo gachchhati, the horse goes. Gajah sarati, the elephant moves; gajo mritah, the elephant died. Xukla puruxah, white man; xuklo manuxyah, white man. Similarly, in ancient Prakrit we see the nominative in ó: Sansk. prasaráh, Prak. pasró, Konk. pasró, shop; pânddurah (whitish), panddrô, pânddrô, king cobra; devarah, devarô, dêr, brother-in-law. Konkani is not in bad company.

The same difference between á and ó is seen in masculine genitive terminations: âmbyáchá = âmbyatsó, of the mango, – in the nominative plural of feminine nouns (ô): gaddyá = gaddyô, cars; and in the verbs (3rd person) (sing., perf. indicative) utthlá = utthló, stood up.

The terminations nem and xim of the Marathi instrumental correspond to n in Konkani, and to lá and s of the dative, k (ko in Hindi, ke in Bengali): âmbyânem (by the mango), âmbyâxim (with the mango) = âmbyan (with or by the mango); âmbyálá or âmbyas, âmbyak (to the mango).

The terminations of the nominative plural of neuter nouns also differ: motyem = motyám, pearls; gharem = gharám, houses.

Konkani has a formal locative on, which Marathi represents periphrastically: mathyár = mátyá var, on top of the head; gharámr = gharám upari, on the housetops.

There are nouns that have one base or theme in Konkani and another in Marathi = hatti (dental tt) = hattyán = háttinem, by the elephant; bhint = bhintyechí = bhintichi, of the wall; khâtt = khâttichem = khâttechem, of the bed.

We have already seen that the nominative and the instrumental of the first-person pronoun are not the same in both languages. Let us now compare other cases and other pronouns. Dative. Mâká (cf. Sansk. mayam, Lat. mihi, which is sometimes pronounced as miki) = mâlá, to me; âm’kám = âhmâlá, to us. Tuka, tulá, tujlá, to you; tum’kam = tuhmâlá, to ye/you. Tâká or teká = tyâlá, to him, etc. Instrumental: tuvem = tvá, for you. Tannêm, tínnem = tyannêm, tinem, by him, by her. The same is to be said of the demonstrative hó, this, and the relative zó, that: hâká, zâká, hânnem, zânnem.

The conjugational differences between the two languages are so many that I do not know how to deal with them in a few words. It would be necessary to reproduce entire paradigms of various verbs to help one get a complete idea. Those who feign ignorance, and those who consider themselves all-knowing, will stay put; those who sincerely wish to study will find half a dozen grammars. But there are some people out there who swear by all gods that Konkani has no grammars and dictionaries comme il faut! Might they have examined them all? And are there many Marathi-Portuguese dictionaries, and vice-versa, and grammars comme il faut? The English put it nicely: ‘Fools rush in where the wise fear to tread.’

I will nevertheless present some corroborative schema as specimens.

Radical sar, to go, pass. Sansk. Sarâmi, sarasi, sarati, sarâmas, saratha, saranti.

Konk. Hámv sartám, tum sartây, tó sartá, ámim sartam, tumim sartát, té sartát.

Mar. Mim sartom, tum sartos, to sarto (m.); mim sartem, tum sartes, ti sarte (f.) mim sartem, tum sartem, tem sartem, (n.) Pl. âhmi sartom, tummi sartám, te sartát.

Lat. Amo, amas, amat, amamus, amatis, amant.

Port. Amo, amas, ama, amamos, amais, amam. [I love, thou lovest, he/she/it loves, we love, ye/you love, they love]

Cast. Amo, amas, ama, amamos, amais, amam.

Ital. Amo, ami, ama, amiamo, amate, amano.

Now, is there not a closer analogy between the flexions of the Romance languages than between those of Marathi and Konkani? And yet there are sharp minds that do not realise it.

Let us juxtapose Sanskrit and Latin flexions. Radical vah-veh: vahâmi = veho, vahasi = vehis, vahati = vehit, vahámas = vehimus, vahatha = vehitis, vahanti = vehunt. Are not these flexions more akin to each other than are those of Konkani and Marathi? Might Latin, then, be a corruption of Sanskrit? There are no people more exacting than the Goans.

Past perfect. Konk.: Hámv sarlom, túm sarloy, tó sarló (m.), hámv sarlim, túm sarliyi, ti sarli (f.), hámv sarlem, túm sarlemy, tem sarlem.

Mar. Mim sarlom, túm sarlas, to sarlá (m.), mim sarlem, tum sarlis, ti sarli (f.), mim sarlem, túm sarlens (n.) Is the daughter a faithful likeness of the mother?

Imperfect: Konk. Sarom, saroy, saro, saromy, sarot, sarot. Mar. sarem, sares, sare, sarúm, saram, sarat.

Konkani has another formal imperfect, made up of the base of the present tense and the flexions of the perfect; and that has no counterpart in the other language: sartâlom, sartaloy, sartâló (m.), sartalim, sartâliy, sartáli, etc.

At the same time, the past perfect, formed by adding ló to the perfect: sarló, it ended; sarloló, it had ended.

Future. Konk.: saran, sarxi, sarat, sarâmv, sarxyát, sartit. Mar.: saren, sarxil, sarel, sarúm, saral, sartil.

How much parity is there between one and the other?

The aforesaid Konkani future is contingent (as Maffei calls it, if you know) or potential: karít, may be able to do it, may wish to do it, maybe doing it, may do it; páus paddat, it may rain, perhaps it will rain. But we have another future, absolute and more assertive, which in Portuguese is expressed as há de [will]: há de chover [it will rain], which differs from choverá [it will rain].[i] Marathi does not have it in a simple form; Konkani, on the contrary, forms it with the flexions of the past tense joined to the base of the present, ending in a (sarta), or to the present participle (sartó): sartalom, sartaloy, sartaló, etc.

-o-o-o-

[i] Both Há de chover and choverá express the future tense, except that that the former is in the periphrastic form.

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 27, March-April 2024, pp 38-41)

The Holy Night of our Lord's Return

The Church today observes solemn vigils[1] for Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost. The Easter Vigil, which begins on the evening of Holy Saturday, has by far the longest, the most ancient, the most sacred, the most profound and most beautiful of all the liturgies of the Catholic Church. St Augustine has called it ‘the mother of all vigils.’

The Easter Vigil is divided into four parts: Service of the Light; Liturgy of the Word; Liturgy of Baptism; Liturgy of the Eucharist, as follows:

SERVICE OF THE LIGHT: This begins outside the church building. Whereas inside, the holy water fonts are drained, the tabernacle is empty and the lights are out; outside a new fire is lit and blessed, as a symbol of life. The priest uses a stylus to cut a cross into a Paschal Candle. Then he makes the Greek letter Alpha above the cross, the letter Omega below, and the four numerals of the current year between the arms of the cross. The Paschal Candle symbolises Christ, the Light of the World, the Beginning and the End, and to Whom all time and ages belong.

The traditional Easter song follows, sung usually by a deacon: the Exultet (Easter Proclamation). ‘This magnificent hymn, which is remarkable for its lyric beauty and profound symbolism, announces the dignity and meaning of the mystery of Easter; it tells of man's sin, of God's mercy, and of the great love of the Redeemer for mankind, admonishing us in turn to thank the Trinity for all the graces that have been lavished upon us.’[2]

LITURGY OF THE WORD: It comprises nine Readings, seven from the Old Testament and two from the New Testament.[3] They help us meditate on God's wonderful works for His people since the beginning of time:

- Story of Creation (Gen 1: 1-2; 2)

- Abraham put to the Test (Isaac) (Gen 22: 1-18)

- Moses and the People crossing of the Red Sea (Exodus 14: 15–15; 1)

- The New Zion (Isaiah 54: 5-14)

- God’s Invitation to His People (Isaiah 55: 1-11)

- In Praise of True Wisdom (Baruch 3: 9-15.32–1:4)

- Renewal of Israel (Ezekiel 36: 16-28)

- Dying and Living with Christ (Epistle, Romans 6:3-11)

- The Resurrection (Gospel, Year A: Mt 28:1-10; Year B: Mk 16:1-7; Year C: Lk 24:1-12)

The Gloria is sung before the Epistle, and the Alleluia before the Gospel.

LITURGY OF BAPTISM: Water is blessed, signifying new life; new members are brought into the Church through baptism and those who were baptized but have not received the other sacraments of initiation. The catechumens and these faithful are confirmed and later receive the Holy Eucharist. Then, the faithful are blessed with water and all renew their baptismal promises, reliving the Resurrection and understanding their identity as a People of God. Part of the liturgy includes the Litany of the Saints.

LITURGY OF THE EUCHARIST: The Mass continues, with special prayers inserted during the Eucharist Prayer, and concludes with a solemn blessing: to defend us from every assault of sin; that we may be endowed with the prize of immortality; that we may celebrate the gladness of the Paschal Feast and come with Christ's help, and exulting in spirit, to those feasts that are celebrated in eternal joy. The Mass closes with the glorious singing of the dismissal: ‘Go forth, the Mass is ended, alleluia, alleluia’ or ‘Go in peace, alleluia, alleluia’.

Clearly, the Easter Vigil liturgy is of exceeding beauty and unending splendour. It is a blessing to be a part of this most sacred night when, together with the sons and daughters of the Church scattered throughout the world, we await our Divine Master’s return in glory. We stay up with our lamps full and burning, hopeful that our Resurrected Lord will give us a seat at His table, that is to say, a share in His triumph over death and life eternal.

-o-o-o-

[1] ‘Vigil’ refers to a day or eve before a prominent feast or solemnity. It is observed with special offices and prayers (and, formerly, a fast as well) as a preparation for the following day, honouring a Mystery or a saint to be venerated on the feast day.

[2] With Christ Through the Year, by Bernard Strasser (Quoted by https://rb.gy/wuibl6 )

[3] ‘The number of these readings can be reduced if some particular reasons and circumstances require so. There should be at least three readings from the Old Testament and in some very particular circumstances these may still be reduced to two, before the Epistle and Gospel. But the third reading from Exodus should never be omitted.’ (Lectionary, Catholic Press, Ranchi, 2011, p. 161)

High: Priest, Drama, Treason

Today, Palm and Passion Sunday, we will reflect exclusively on St Mark’s Gospel text (14: 1-15, 47), which is dense and rich in concrete details. For a reflection on the other two Readings of the day, which are common to all three cycles, please refer to https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2022/04/10/from-palms-to-the-passion/ and https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/04/02/the-suffering-servant/ , my blogposts of 2022 and 2023, respectively

-o-

Several incidents precipitated a crisis two days before the Passover and the Feast of the Unleavened Bread[1]: Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem; the cleansing of the Temple, and the spin-off indicating the end of Jerusalem and the Temple; Jesus’ authoritative teaching and claims to Divine Sonship; the miracles He worked and the growing multitude around him. All this added up to a situation that could not be ignored.[2]

Hence, the high degree of tension between the Temple aristocracy and Jesus’ supporters at large, symbolised, on the one hand, by the chief priests and the scribes who sought to arrest Jesus, and on the other, by the grateful woman who broke open the lid of her alabaster jar of pure nard ointment and poured out her love.

There was also high treason, best symbolised by the Judas kiss. Jesus was spot on: ‘Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me… one who is dipping bread in the same dish with me.’ That was insider betrayal out of greed which even made Peter’s denial out of fear look banal: whereas Peter disowned His Master, Judas sold Him. And we have it from our Divine Lord: ‘For the Son of Man goes as it is written of Him, but woe to that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed!’

Profound words these that would not apply, for instance, to Peter, James and John (the same trio from Mount Tabor) who Jesus thrice found sleeping, unable to keep watch with Him, who was distressed in the Garden of Olives, sat and prayed: their fault was accidental, unpremeditated, for their spirit was willing but the flesh was weak.

On the other hand, absolutely premeditated were the actions of the chief priests, the elders and the scribes late that night. When they sought testimony against Jesus, many bore false witness; when the testimony failed to agree, the high priest took it upon himself to accuse Jesus, and the temple aristocracy joined in condemning Him to death. The garment tearing by the high priest was a sign of outrage prescribed for an officiating judge in the face of blasphemy. [3]

The Sanhedrin, or supreme council and tribunal of the Jews, had religious, civil and criminal jurisdiction. But theirs was more of a cross examination than a trial per se.[4] Early in the morning they handed over Jesus to the Roman Governor Pilate, who held court at that hour, ‘since only the Romans could carry out the death sentence’. To clinch it, the temple authorities emphasized their verdict’s political dimension: Jesus’ claim of messianic kingship, threatening the Pax Romana.

On the other hand, Pilate, especially at his wife’s bidding, indeed took Jesus to be the ‘King of the Jews’. He knew that it was out of envy that the chief priests had delivered him up. Nonetheless, he gave in to them and to the customary public acclamation that, much to his chagrin, favoured Barabbas, a rebel against Roman power and murderer in the insurrection – both of which Jesus was not. That much was enough for Pilate to be on the side of Jesus, whose alleged offence against the Torah did not concern him as a Roman. ‘Why, what evil has He done?’ asked Pilate, but feebly. Then, he played to the gallery; without pressing for coherent answers, he delivered him to be crucified, so as not to risk his own career.

Then in the praetorium (Governor’s residence) there erupts over Jesus ‘the brutal mockery of those who know they are in a position of strength… He whom they had feared only days before was now in their hands. The cowardly conformism of weak souls feels strong in attacking Him who now seems utterly powerless.’[5] They mock him, strip him, and lead Him out to crucify Him. Most likely they are supporters of Barabbas.

And what of Jesus’ supporters? They probably remained hidden out of fear. In a way, they too betrayed Jesus, like so many who fail to bear Him witness today. That is when passersby step in and do the honours. Look at Simon of Cyrene,[6] who promptly agreed to carry Jesus’ cross to Golgotha, while the womenfolk[7] looked on, helplessly, from afar. And finally, when Jesus breathed His last, and the curtain of the temple tore in two, the centurion (Roman commander) exclaimed, ‘Truly, this man was the Son of God!’

A late realisation, almost in vain? Yes, but Jesus’ death was not in vain. ‘God put [Jesus] forward as an expiation by his blood’ (Rom 3: 23, 25) All things considered, Caiaphas’ words about the need for one man to die, to save the nation (and the world, as St John points out) fulfilled the content of Jesus’ mission. And alas, in a moment of high drama, the Jews, declared, ‘We have no king but Caesar’, unwittingly siding with Rome and renouncing Israel’s messianic hope.

The irony of ironies is that in 70 A.D. both Jerusalem and the Temple were destroyed by the very Romans that the Jews had sided with, for it was written, ‘I will strike the shepherd and the sheep will be scattered.’ And then they had no Jesus to rebuild it.

[1] Passover is the first night of the seven-day, annual feast of unleavened bread during which the Israelites ate only unleavened bread, as a commemoration of their Exodus from Egyptian bondage. Since they left Egypt hastily, with no time to let the bread rise, they made their bread without leaven (yeast) on that very first Passover night.

[2] Cf. Joseph Ratzinger, Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week, p. 168.

[3] Gnilka, Matthausevangelium II, quoted by Joseph Ratzinger, p. 178.

[4] Op. cit., p. 176

[5] Op. cit., p. 182

[6] There is no indication that Simon knew Jesus. He was a Jew who resided in North Africa and happened to be in Jerusalem at the time of the Crucifixion, and later became his disciple and missionary.

[7] ‘Mary the mother of Joses’: Joses was a relative of Jesus.

Faithful to the End

Last Sunday, we had a look at the Davidic covenant that in due course would be replaced by the New Covenant. Today, Jeremiah the prophet preannounces this Covenant, while Jesus explains its nature: a covenant of love based on His death on the Cross. It may be noted that the earlier covenants were provisional, of a material nature, and linked to a nation; they were a long preparation for this new, spiritual, eternal and universal Covenant.

That explains the joy with which the otherwise ‘Weeping Prophet’ Jeremiah makes the announcement to the Judeans exiled in Babylon. You will hear him thus in today’s First Reading (31: 31-34): ‘Behold the days are coming, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah…’ This was not a covenant to be engraved on stone, as in the days of old, but upon hearts (which the Jews regarded as the seat of wisdom and willpower).

Would the survivors of the two divided kingdoms honour the covenant? The answer would manifest itself when Jesus came to the world four centuries later. Meanwhile, the cold reception that the Divine Babe received that December night foreshadowed His ministry’s lack of ‘success’ (as the world sees it). But it was not God that failed – He never will – but the Jewish people who had failed their God. Their bad decisions came home to roost. Look at how the Jewish state crashed at the hands of the Romans in 70 AD – a vindication of what Our Lord had foretold. The issue of the Jewish dispersion, persecution and later unification still dogs contemporary world affairs. The problem with the Jews was that they had their eyes set on their country’s freedom and glory; but alas, in their worldliness, they failed to see that mighty sin militated against their lofty wishes.

As for the Son of God, he was precisely targeting the destruction of sin. He did not come to the world to save His country as the people would like it, but to save His people from their greatest enemy – sin. He would even die to destroy sin, but none of that seemed to matter to the political and religious leaders and their hangers-on in Jerusalem. They were all so self-centred, and warped in their doctrine, that their country was their everything. They were convinced that the world would be saved through them alone.

The Scripture, on the other hand, was clear as daylight, yet the Jews failed to see the writing on the wall. Had not Isaiah (56: 6-7) quoted God as follows: ‘the foreigners who join themselves to the Lord [...] these I will bring to my holy mountain [...] for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples’? This came to pass in today’s Gospel text (Jn 12: 20-33), when Gentiles – Greeks to start with – sought a meeting with Jesus. They first approached Philip, attracted by his Greek name, and Andrew took them all to Jesus. Here is an indication that the Lord would not wait indefinitely for the Jewish people to take the Covenant seriously. His hour had arrived....

The hour had indeed arrived for the Son of Man to be glorified on the Cross. But what glory was there in dying? In the eyes of the world, none! But God’s ways are different from our ways... To get the message across, Our Divine Master employs the analogy of a grain of wheat that falls to the ground and perishes, to bear much fruit. By the same token, when you and I die to ourselves (that is to say, set aside our sinful ways and embrace God’s) we will be born again; he who ‘hates his life in this world’ (loves God more than self) will save himself for eternity. Jesus showed the way by accepting his imminent death – and soon a voice from Heaven endorsed it, saying, ‘I have glorified it [in the river Jordan and at Mount Tabor], and I will glorify it again.’

Now, could the voice from Heaven be Greek to anyone who had ears to listen? The Chosen Race would soon be seen in their true colours. For His part, Our Lord, with loud cries and tears (which attested to His human side) offered up prayers and supplications to His Father who could save Him from death, but at the same, remained obedient and faithful to the end, as we learn from the Second Reading (Heb. 5: 7-9). In this way, Jesus became the source of salvation to all who obey Him and now challenges us to entrust our lives into His hands. He is always faithful; it is we who fail Him… and finally, through our own fault, fail miserably in our endeavours! He longs for us who are made in His image and likeness, but sadly, we wander away.

This Lent, therefore, let us resolve to change our ways, praying: ‘A pure heart create for me, O God!’ (Ps 51: 12) Let us humbly seek His mercy, kindness, compassion. Let us also pray for other transgressors and sinners like us: that we may form a community ever faithful to the Lord our God and be blessed with the joy of His help.

Konkani Saga in the Roman Script

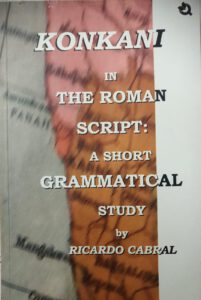

The Konkani language is written in many scripts. Ricardo Cabral’s latest offering, Konkani in the Roman Script: a Short Grammatical Study, is a welcome addition to the limited bibliography on the subject. It maps out Konkani’s saga from the time Roman script made an entry into Goa, in the sixteenth century; and more importantly, the book earnestly proposes a modified script.

Before elaborating on the historical “Romanization process”, Cabral looks at fragments of the linguistic history of the mull Goenkar (original natives): the Gauddas and Kunnbis living around the foothills of the Verna-Nuvem plateau. Stating that “the first dialect that has to be taken note of is the Gaudda/Kunnbi dialect”, the author goes on to list its salient phonetic and syntactical features.

Konkani developed a complex structure comprising dialects from the North (up to Malvan) and South (up to Mangalore), with Antruzi, Kunnbi, Shashti, Bardezi and Koli forming the central group. As a result of the immigratory waves from the north and south of the present-day territory of Goa, different dialects of Konkani got integrated down the centuries. That was the position at the time the Christian missionaries began what would turn out to be a grand linguistic enterprise. The Jesuits and the Franciscans naturally chose to write in the Roman script, which was common to Portuguese, Latin and English, and was easier to print.

Cabral traces three developmental phases of Konkani in the Roman script: first, what he calls the Eureka phase, “when all things for the foreign missionaries were objects of wonderment” (16th-19th centuries); then, the middle or Bombay Blast phase (end of 19th to mid-20th century), for the then British Indian metropolis was the nerve centre for Konkani productions in the Roman script; and finally, the modern, consolidation phase (mid-20th to early 21st century). Noting that it was not simple for the missionaries to transcribe the sounds, much less standardise the orthography, Cabral gives examples of how writing in Konkani evolved from being heavily dependent on Latin and Portuguese phonology to trying to find an independent script in contemporary times.

It is not clear why Cabral titles the second chapter “Etymology” when it deals with word or lexical classes as in a traditional grammar. Verbs are then treated more in detail in the third chapter; and it is only in the fourth chapter that we catch a glimpse of the alphabet. It is not always easy to find apt English examples to illustrate sounds in Konkani; quite understandably, the pronunciation chart of vowel-and-consonant sounds in Konkani (ê; fuloi) and their respective phonetic illustrations in English (say /eɪ/; ‘boy’ /ɔɪ/) has a few mismatches.

Whereas the phonetic transcription of some Portuguese words needs to be revisited (e.g. fixo is not /fikso/ but /’fiksu/), the author is right about how hard and soft sounds can make or break. For instance, in church and elsewhere, readers and speakers often fail to distinguish between killo and kil’lo, mellem, mel’lem and mell’lem. Cabral’s table of allophones thus comes across as a valuable learning aid for a language loaded with a variety of phonemes and graphemes.

The general reader is sure to enjoy the chapter on word formation. Cabral elaborates on three types of Konkani words: primitive, derived and loaned. ‘Reduplication’ is an interesting, largely onomatopoeic, process that Konkani words have undergone, giving us picturesque words like khoddkhodd (shivering), davon-davon (hurriedly), poishean poiso (every paisa), and so on. Cabral gives a sprinkling of loan words from Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Kannada, Portuguese, French, Marathi, English, Tullu and Hindi. However, the cited ghurghuret (water pot) is not originally a Konkani word but corrupted from the Portuguese gorgoleta.

In chapter six, ‘Morphology’, Cabral lists hyponyms, homonyms, homophones, polysemes collocations, and so on. And whereas in chapter seven, we find a conventional treatment of Syntax, with a good dose of illustrations, the subsequent chapter tackles a relatively new area: Generative Grammar. Cabral deserves credit for the structural analysis undertaken, by devising much needed test-frames for sentences and tenses in the language. It is a brave effort to modernise the grammatical approach to the Konkani language.

In the said chapter, Cabral also presents a modified alphabetic principle, in an attempt to rationalise the Roman script for Konkani; he highlights the differences between x/sh; i/y; d/dd; t/tt; n/nn and proposes the tilde as sole nasal marker, allowing m and n to be used exclusively as consonants. His makes a compelling case for well-defined orthographic rules, a step in the right direction.

In the penultimate chapter, on Ergativity, Cabral correlates Konkani with Latin and Sanskrit. He states that, there being no formal passive voice in Konkani, past and perfective tenses double up as seemingly passive in some tenses of transitive verbs. He indicates three ways to tell between transitive and intransitive verbs in Konkani. His catalogue of over 300 transitive and intransitive verbs, with their exceptions and meanings in English, is a ready reckoner.

At the end of a full course meal, the closing chapter, titled ‘Miscellaneous’, is a veritable dessert. It offers close to a hundred idiomatic expressions; several figures of speech; interesting proverbs; many puzzles and riddles (parkhonni/umanni); person and place names in Goa; and a handy glossary of a thousand Konkani words. Much as the book could do with tighter editing and better proofing, readers are sure to be charmed by its final chapter.

Ricardo Cabral, PhD, a teacher educator by profession, who retired from the Goa State Council of Educational Research and Training (SCERT) and has authored two books on education in Portuguese Goa, is deeply concerned about how Konkani in Goa has to reel under tremendous pressure from India’s two official languages: Hindi, given the large-scale immigration of its speakers; and English, given the Goan penchant for the language. He fears that soon there may be very few Goans speaking Konkani. Hence his effort – “to make the knowledge of Konkani available not only to those who want to learn the language but also to those who want to learn about the language, especially Goans in the diaspora” – is something that Goa ought to be grateful for.

KONKANI IN THE ROMAN SCRIPT, by Ricardo Cabral (Panjim: Qurate Books, 2023. Rs 735/-)

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 27, March-April 2024, pp. 63-65

https://online.fliphtml5.com/bcbho/agcy/#p=1

Love Him, who is the Light!

On the fourth Sunday of Lent, we look at the Davidic covenant that, like the previous ones, was not respected; it was eventually replaced by the New Covenant, with the coming of Jesus Christ, Son of David, as the Light of the world.

Today is also called Laetare Sunday, from the first few words of the traditional Latin entrance verse for the Mass of the day. ‘Laetare Jerusalem’ (‘Rejoice, O Jerusalem’) is Latin from Isaiah 66: 10.

In the First Reading (2 Chron 36: 14-16. 19-23) we see that the people of Judah had failed to keep the covenant; they had ‘polluted the house of the Lord’ and mocked at God’s messengers. Then the inevitable happened. In 597 BC, King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon captured Jerusalem and sent the king and his people into exile. For 70 years thereafter, they turned to God in their desolation and kept sabbath holy. Eventually, God in His mercy inspired the Persian king Cyrus, who had by then conquered Babylon, to let the Jews return to Judah and rebuild the Temple that the Babylonians had destroyed.

This Second Temple was awe-inspiring from the religious as well as architectural point of view. But alas, it was only a marvellous shell disguising the emptiness of the people’s lives. Not only did Judah continue to be coveted by foreign rulers, including the Greeks and the Romans; to curry favour with the authorities, the Jews were willing to offer sacrifices to their deities. Herod even erected a golden Roman eagle on the Temple. The Pharisees rose partly as a reaction to the Jewish submission to foreign influences and syncretistic practices (but eventually the remedy became as serious as the disease)….

It was against this background that, five centuries later, God sent His Only Son Jesus to announce the Good News of Salvation. Jesus frequented that very Temple, preached there and even cried at the thought of its impending destruction. He presented Himself as the Temple of God – but He was misunderstood, maligned, rejected. When He promised to rebuild the Temple in three days, He was referring to His own Death and Resurrection. But the people who cared not to see beyond the end of their noses wrote Him off. And the rest is history. Jesus built His Holy Church, to which we are happy to belong, whereas in 70 AD the Jewish Temple was reduced to rubble by the Romans and there began the dispersion of the Jews.

That throws into sharp focus what Jesus says to Nicodemus in today’s Gospel text (Jn 3: 14-21): ‘As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of God be lifted up, that whoever believes in Him may have eternal life.’ And then He cautions: ‘He who believes in Him is not condemned; he who does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the Only Son of God.’

It is interesting to note that Nicodemus was a Pharisee and member of the Sanhedrin; he, who admired Jesus’ teachings, first visited Him at night! He was quite likely a secret disciple and is known to have reminded fellow members that Jesus had a right to a hearing before being judged. He appeared next after Jesus’ crucifixion, bringing along the customary spices to anoint the dead body – a large amount at that, which turned it into a “royal burial”,[1] in the words of Pope Benedict XVI, in his book Jesus of Nazareth.

Meanwhile, what is that 'serpent in the wilderness' that Jesus refers to in his conversation with Nicodemus? It refers to a scene from Numbers 21, where the Lord had told Moses to lift up a pole with a bronze serpent on it, so that whoever looked upon it would be healed and delivered from God’s judgment.

Likewise, we must regard Jesus on the Cross as our only salvation! But do we? It isn’t an exaggeration to say that the Christian world stands in need of liberation from many temptations and vices. It is as though we too have ‘polluted the house of the Lord’; we are indeed walking the tightrope with syncretic and idolatrous practices, putting the Lord to the test. We are destined to have a share in the kingdom of God, in God's eternal life, yet we go to pick up two pennies in the street, risking the loss of that great fortune.

Let us not be half-hearted or just secret admirers of Jesus Christ. Let us come out into the open and declare our allegiance and solidarity. Rightly so, for with Him we have everything; without Him, nothing! Without Him, we would be condemned and dead already. St Paul in the Second Reading (Eph 2: 4-10) calls our attention to the fact that ‘God, who is rich in mercy, out of the great love with which He loved us, even when we were dead through our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ (by grace you have been saved), and raised us up with Him.’ He is indeed the Way, the Truth and the Life. He is the Light.

Let us be children of the Light and love Him who is the Light of the World. Only then will the New and Eternal Jerusalem rejoice.

[1] Ratzinger, Joseph. Jesus of Nazareth. Holy Week: from the entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection. California: Ignatius Press, and Bangalore: Asian Trading Corporation, 2011, p. 228.

Calling a spade a spade

On the first two Sundays of Lent, we pondered the Noahic and Abrahamic covenants. This Sunday, we dwell on the Mosaic covenant, one of whose highlights is the ban on the worship of false gods. This is a central idea of our faith, echoing as it does in the Gospel text that shows Jesus in an unprecedented act of expelling those who had desecrated God’s house. He is the God of mercy and love, but also of justice and zeal for His Father.

The First Reading (Exod. 20: 1-17) reminds us of the identity of the Lord our God. He delivered not only the Jews, out of bondage, He delivers us at every moment of our lives. How, then, can other gods ever flash before our eyes? Our loyalty must be only to our God who saves! Let alone inanimate, graven images; we ought not to bend down or serve any other idol – things or humans (many of whom, alas, have sold their souls!)

God has issued the Decalogue for our easy reference and guidance; whoever bypasses it, does so out of convenience or arrogance, not inability. And woe to those who think they can pull the wool over our eyes. No manner of theological deftness, in an attempt to please everyone, can hoodwink God…. Then, why can’t we simply call a spade a spade? Isn’t our communication supposed to be ‘yes, yes; no, no’? (Mt 5: 37) If not, the claim that when God is for us none can be against us (cf. Rom 8: 33) will come across as mere rhetoric…

In today’s Gospel text (Jn 2: 13-25) Jesus is portrayed as our role model par excellence. He acted single-handedly and single-mindedly, against those who had idolised mammon. ‘Think ye, that I am come to give peace on earth? I tell you, no; but separation,’ he had forewarned. And separation is what He brought about between the authentic and the fake in His Father’s house. He drove the latter out with a whip of cords and overturned their negotiating tables. His disciples remembered that it was written, ‘Zeal for Thy house will consume me,’ and this was now playing out before their very eyes.

Humanly speaking, we tend to think that Our Lord was wrong in what He did. That is not true; Our Lord proceeded with extreme care, but did not fail to do what He had to do – to call a spade a spade! According to the Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich, who experienced visions of the life and passion of Jesus, Our Divine Master had gently admonished the vendors on an earlier occasion, corrected them on a second, warning them that he would act on the third occasion, if any.

It is no surprise that the Jews tried to checkmate Jesus, saying, ‘What sign have you to show us for doing this?’ During Our Lord’s three-year public ministry, there were signs galore – healing the sick and bringing the dead back to life; what else could one ask for? Besides, it was all written in the Jewish scriptures, from times immemorial; the Pharisees and the Scribes, the teachers and leaders of Israel, knew it all very well – ever since they sighted the Star of Bethlehem! There was obviously a lot of malice in trying to play that down.

It was now already the eleventh hour. The time for the final showdown had arrived. However, when Our Lord announced that He would destroy the temple and rebuild it in three days, the said dissenting Jews were flummoxed. With them was fulfilled Isaiah’s prophecy, which said: ‘You shall indeed hear but never understand, and you shall indeed see but never perceive.’ (cf. Mt 13: 14) ….

And what about you and me? It is as though the rest of Isaiah applies to us! Haven’t our hearts grown dull; aren’t our ears heavy of hearing and our eyes closed? Note Our Lord’s words to those who take Him for granted: ‘Truly, I say to you, many prophets and righteous men longed to see what you see, and did not see it, and to hear what you hear, and did not hear it.’ (Mt 13: 17)

Let us, therefore, appreciate that God’s commandments help us establish a personal rapport with God and our fellow human beings. To us who are in pursuit of the truth, they provide a roadmap and spare us the pressures of our crazy times. But then, are we any different from the Jews who expected signs, and the Greeks who demanded knowledge?

St Paul in the Second Reading (1 Cor 1: 22-25) says that Christ was a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles. What about us? Are we ready to preach Christ crucified and stand by the folly of the Cross? Let us ask the Lord our God for the light to see His commandments clearly; for the strength to act accordingly, calling a spade a spade; and pray for that much needed grace to get to the depth of the Paschal Mystery.

Matter of life and death

There is a culture of life and a culture of death. Quite ironically, while we live in a world that prizes life, we are continually surrounded by agencies of death. We feed the body and starve the soul; we value the life of the body and have no qualms about the death of the soul. Ours is therefore a life in death, and the sooner we realise it the better.

Against that backdrop, can the First Reading (Gen 22: 1-2, 9, 10-13, 15-18) make any sense to contemporary man? That Abraham could instantly agree to sacrifice his son to please God, may seem absurd; we may even dismiss the passage as fictional.

The fact is that Isaac was a son of promise, so how could God ask for a sacrifice? But then, Abraham suspended his judgement and was ready to do so, as a sign of his faithfulness to God who had given him the son. His unparalleled act of faith prompted God to announce a beautiful plan, as seen from the following words he said to Abraham: ‘I will indeed bless you, and I will multiply your descendants as the stars of heaven and as the sand which is on the seashore.’

But alas, Abraham’s descendants betrayed his faithfulness; they systematically spurned multiple divine covenants – until God deigned to send his only Son Jesus to the world, in a striking parallel to Isaac’s life and death. Both Isaac and Christ were only sons, born supernaturally, as sons of promise; both came with the message that God still loved the world; both were sacrificed, on mount Moriah, which, if not the same as Golgotha, is thereabouts. Thus, Isaac was the symbol, Jesus the Reality.

St Paul in the Second Reading (Rom 8: 31b-34) sets us thinking: ‘He who did not spare his own Son but gave Him up for us all, will he not give us all things with Him?’ Of course, He will. And if God is for us, who can be against us? If this be true, what is the point of ‘the weariness, the fever and the fret / Here, where men sit and hear each other groan’? Or as another poet put it, ‘What is this life if, full of care, we have no time to stand and stare?’ In fact, in the present chapter of the Letter, St Paul sings a paean to God’s faithfulness and love.

Elsewhere, the Lord reminds us of a truth that often goes unnoticed: ‘Look at the birds of the air; they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?’ (Mt 6: 26) Indeed, we are. Why, then, can’t we stop worrying and start thinking of how best to let His kingdom come, on earth as it is in Heaven? Let us believe and trust in Him who knows and can do all things; let us gaze at His face.

Today’s Gospel text (Mk 9: 2-10) reveals to us Jesus’ purpose of taking with Him Peter and the two Sons of the Thunder, James and John, up a high mountain apart by themselves: He did so to let them know His identity and destiny. And they, who would soon be destined to witness the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, would better have their faith fortified right away.

Then, Jesus was transfigured before them. Peter, afraid and not knowing what to say, proposed to build three tents – for Jesus, Moses and Elijah. In fear and at the same consoled by what he had seen, he succumbed to the human tendency to bring the supernatural down to the natural. But when there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, who spoke to Jesus, it was clear that the Transfiguration was no mean event, surely not something about relaxing or standing or staring. And what is more, a cloud overshadowed them, and they heard a voice saying, ‘This is my beloved Son; listen to Him.’

What else do we need to convince ourselves that Jesus is our Lord and God? Not only does His divinity stand confirmed, the prophetic role of Elijah and the leadership of Moses are endorsed. As for us today, it ought to convince us to ‘strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well.’ (Mt 6: 33). In short, we have to be transfigured to be entitled to participate in the Lord's Resurrection.

We require nothing other than His message, to realise that earth is a temporary tent; that those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for God’s sake will find it? (cf. Mt 16: 25). This is indeed a matter of life and death, and Lent is here to let us know.

Let’s walk right back to God!

Lent is an apt time for reflection and introspection. The Readings are so designed as to let us delve deep into our Christian being. They recall the times when God interacted with man and, closer to our times, sent His Only Son to the world. They take us back to the basics, showing a consistent theme running from the beginning of humanity to our days.

The First Reading (Gen 9: 8-15) speaks of the first Biblical covenant between God and humankind, in the person of Noah. After the deluge, when a new humanity arose, purified by the waters, God promised to never again flood the earth. God stooped down to hug humanity in a touching scene of an everlasting love.

It may be recalled that the Noahic covenant had become necessary after the one established with Adam had failed. In the Gospel text (Mk 1: 12-15) we encounter the Second Adam, Jesus Christ: He is tempted in the wilderness, just as Adam and Eve were in the Garden of Eden, but unlike them, Jesus stands up to the forces of evil.

Our Lord’s exhortation – ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent, and believe in the Gospel’ – is thus a clarion call to reflection and introspection that will lead to repentance. The wilderness is a privileged place for Jesus’ encounter with the Father; the forty days of solitude that He spent there evoke the forty days that Moses spent on Mount Sinai and the forty years of God’s people in the desert. Our Lenten season is a reenactment of those days.

You and I live in a worldly wilderness, a moral desert, a spiritual wasteland. But we may rest assured that, like the angels who ministered to Jesus while he was tempted by Satan, our Baptism helps us to withstand the evil forces of the world. We are not told explicitly what the ‘kingdom of God’ consists of, but a certain realisation wells up in the deepest recesses of our hearts, in the form of our inner conversion; it is a promise that we will one day partake in the merits of the Lord’s Resurrection.

Finally, St Peter in the Second Reading (1 Pet 3: 18-22) draws a parallel between the water that saved Noah’s eight and the water of Baptism that saves us. It speaks volumes of the Lord’s faithfulness. As the Psalm sings, ‘Your ways, Lord, are faithfulness and love for those who keep your covenant.’

Our prayer therefore should be that the Lord teach us His ways and let us walk in His truth; that He have mercy on us and remember us. There is no place for doubt, for the Lord is good and upright. However disastrous the circumstances of our lives may be, He shows the path to those who stray. Lent is thus that period par excellence when, with a contrite heart, we may walk right back into God's bosom.