Pondering God’s commandments, with love

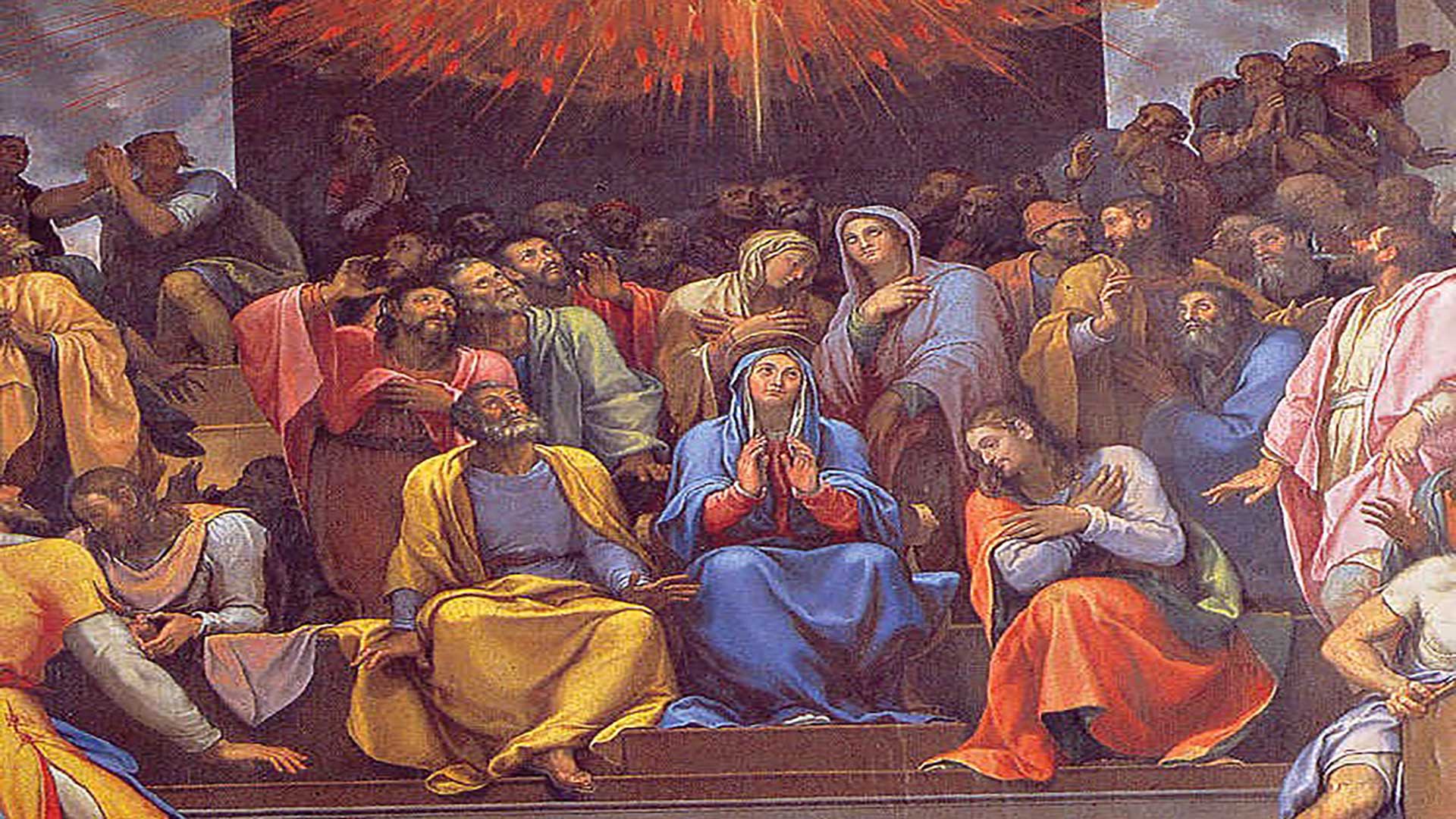

As we inch towards the Ascension and Pentecost, we see heartening changes in the incipient Christian community. In the First Reading (Acts 8: 5-8, 14-17), we meet Philip, one of the seven deacons. He is presently in Samaria, where his preaching fell on good soil. The people were in awe of his words and miracles, and relieved on being delivered of evil spirits. On hearing that encouraging update in Jerusalem, apostles Peter and John were dispatched double quick to lay their hands over the Samaritans and pray that they too receive the Holy Spirit.

Samaria awaited a Messiah but was traditionally considered idolatrous ever since a temple to Baal was erected there by King Ahab. So, why was the region suddenly privileged to be in the forefront of evangelisation? Philip had ventured there because Jesus Himself had preached in the area (cf. the story of the Samaritan woman at the well) and wished that the Gospel be taken there after His ascension. Thus, Jesus implied that the Good News of Salvation was meant to reach one and all. It is doubly significant that Philip, not an apostle but a deacon, whose main job was to relieve the apostles of menial chores, became the first foreign missionary in Christian history.[1]

The act of reaching out to Samaria has since had far-reaching implications. The church in Samaria was to Jerusalem what a local church today (say, the archdiocese of Goa and Daman) is to the universal church. The arrangement throws light on the very meaningful hierarchical structure that has governed the Church for the last two millennia; it speaks volumes for the issuance and teaching of doctrine centrally, from the headquarters in Rome, so that all of Christendom is of one mind; and finally, it points to the communion of saints, or say, the fellowship of those united with Christ across space and time.[2]

For Christ to be present with His people across space and time is no mean feat; but to God nothing is impossible. It is a fulfilment of what Our Lord had promised in his farewell discourse, just before His Passion and Death. He had said that after His Ascension, the Holy Spirit would be with the Christians till the end of times; the Spirit of truth would pick up from where He had left off, to illumine and strengthen all the faithful. There is no denying that, inasmuch as we keep the commandments, we grow in wisdom and stature, and live in spiritual unity and love of God. God is then always in our midst.

But, really speaking, who has the strength to keep the Lord’s commandments? Only those who love Him will do so, says Jesus, quite plainly, in the Gospel today (Jn 14: 15-21). Yes, it demands total commitment – difficult, but not unreasonable or impossible. Don’t spouses, children, bosses, friends, clubs, expect the same? Don’t we, then, respect rules and keep promises; and when we don’t, we quit – or are obliged to quit? Why, then, should a relationship with the divine be any different? In fact, our commitment should have been infinitely stronger; but alas, it isn’t, simply because for far too long we have been accustomed to taking God for granted. ‘God will understand’ is a lame explanation, and a convenient ruse to flout rules and break promises.

Concretely, let us look at the First Commandment: "You shall worship the Lord your God and Him only shall you serve." It summons us to believe in God, to hope in Him, and to love Him above all else. "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul and with all your strength" (Deut. 6:5). Adoring Him, praying to Him, offering Him the worship that belongs to Him, fulfilling the promises and vows made to Him are acts of the virtue of religion.

On the other hand, superstition is a departure from the worship that we give to the true God. It is manifested in idolatry, as well as in various forms of divination and magic. Similarly, atheism is a sin against the first commandment, since it rejects or denies the existence of God.[3] Yet, what is the in-thing? To keep God out of one’s day-to-day dealings, if deemed socially and/or politically expedient. This is the antithesis of the First Commandment that we are expected to profess and practise; what the score will be on the remaining nine is anybody’s guess!

St Peter in the Second Reading (1 Pet 3: 15-18) therefore counsels us to revere Christ as Lord; defend those who are on God’s side; do the right thing, in the right way, so that none can point an accusing finger at us. “For it is better to suffer doing right, if that should be God’s will, than for doing wrong,” he adds. We ought to muster courage by summoning up the memory of Our Lord’s undeserved death for our sins. As regards us, we run the risk of being hated or even put to death for siding with God, but we may rest assured that we will be made alive in the spirit by the same God who has conquered sin and death: Jesus Christ our Lord.

A tall order? If we listen to God’s commandments – with our minds and hearts – pondering what they mean to us here and now, we will invariably be assisted by the Holy Spirit. As Jesus has cautioned, the dark world of unbelief is incapable of understanding and accepting the Spirit of truth – which will be accessible only to those who love and revere Him!

[1] Philip famously converted an Ethiopian eunuch, thus inducting a black into the church at a very early stage. Then he proceeded to evangelise other areas up to Caesarea; Greece, Syria and Phrygia.

[2] Those living are said to constitute “the church militant”, while the dead who are in Heaven, “the church triumphant”, and those in Purgatory, “the church suffering”. Yet the three groups are in communion of the Spirit.

[3] Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P7G.HTM

With eyes of faith

It must have been exciting to be part of the early church. Yet, look how there was disagreement and discrimination at its very inception (Acts 6: 1-7). The Hellenists, Greek-speaking Jews who had returned from the Diaspora, felt discriminated against by the Hebrews, who were local, Aramaic-speaking Jews. Fortunately, to prevent mundane concerns from sapping their energy (in this case, Hellenic widows receiving second-class treatment in food distribution), the Apostles appointed seven helpers or deacons to take care of those worries. Of course, these seven were men of faith and filled with the Holy Spirit; while they helped safeguard social cohesion, the Apostles immersed themselves in the work of evangelisation.

Such wise principles have governed the church ever since. To illustrate it with something very familiar to us, the early church in Goa set up Fábricas to look after the temporal affairs of the parish, while the Confrarias or brotherhoods focussed on spiritual matters. It is not that Fábrica members were worldly-wise and only the confrades holy; faith and morality were essential to membership of either association. But, all in all, the arrangement brought balance to the individual and the community…. Have we strayed from those guiding principles, and consequently, are those bodies now a far cry from what they were meant to be?

Not those bodies alone – but our own bodies and souls are in need of d-e-l-i-v-e-r-a-n-c-e – deliverance – prayer to bring healing and wholeness to us who are struggling with bondage to sin and demonic influences. Haven’t many of us Christians – and, sadly, some of our leaders too – rejected the living stone that in God’s sight is “chosen and precious”? That living stone is Jesus Christ, the Son of God. In the world today, and Goa in particular, it is high time we realised our folly and decidedly turned back; before long the rug will be pulled out from under our feet by the very people that we had once blindly trusted. Alas, it will be a mighty fall, which only a mighty exercise in faith can prevent – deliver us from! The recent happenings in Manipur are a case in point; living stones are sought to be smashed and life snuffed out of the living church.[1]

St Peter (1 Pet 2: 4-9) calls us to be living stones and build ourselves into a spiritual temple. Well, one can lead the horse – er, the sheep – to the water but can one make it drink? We have built magnificent houses of God, but how many care to drink deep of the knowledge of God? The first Apostle reiterates that we are “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation”, and our bounden duty, to “declare the wonderful deeds of Him who called you out of darkness into His marvellous light”! Once again, for us in Goa, it is important that we open our eyes to the gift of faith that our ancestors have handed down to us; and it is equally a matter of gratefully passing on that faith – in a pristine condition, that is – to the communities around us. Only then can we think of ourselves as ‘living stones’ of the local and the universal Church.

A proper reflection on our first Pope’s enduring call will not only make our (Sun)day, it will have a considerable bearing on our community life for generations to come. In the wake of that tragic update about Goan Catholics straying into forbidden territory,[2] the Gospel today couldn’t be more pertinent. In answer to Thomas, that courageous Apostle who travelled to India, Jesus, in his farewell discourse at the Last Supper, said: “I am the Way, the Truth and the Life”!

How many times do our shepherds have to drum this message into us – seventy times seven? We the flock should not presume that it will always be possible for our shepherds to go in search of their sheep and bring them back to the fold, restore and heal them! Very often we will have to remember these lessons ourselves or learn them from our somudai or community, which have to rise to the occasion in prayer and a spirit of service.

The Gospel passage (14: 1-12) speaks so unambiguously to us that we almost hear Jesus’ say: “Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me?” How come we still do not know the Master’s voice? Do we not believe that He is God, that He is in the Father and the Father in Him? Ever since He became Man, He is within our reach. Haven’t we in Goa had Jesus for the past half a millennium and more? What is the use of declaring from the rooftops, “bhavarth amcho nhoi aicho kalcho, punn Sam Fransisk Xavieracho” (Our faith is not of recent origin; it goes back to the days of St Francis Xavier)[3] if we continue to set our eyes on the idols that the Apostle of the Indies had got out of our sight?

Today, let us reaffirm our resolve to follow Him who is the Way, the Truth and the Life. Let us keep the faith; let no other, however exalted his position, destroy it for us by presenting pastures new. As Jesus has twice said in Jn 14, “Let not your hearts be troubled”! And, yes, let us not depend on our physical eyes to see Him; we can see Him with eyes of faith (below, a hymn to help us reinforce it). We ought only to root out misplaced customs and usages, and let the words of Jesus take root in our souls instead.

| Tuka amim polleunk nam (1 Ped 1, 8)

Tuka amim polleunk nam, punn Tujer amcho bhavart, Jezu amchea Taroka! Jezu, sorv utram Tujim sasnnachea jivitachim: konna-xim vochum ani!

Tuka amim polleunk nam, punn Tujer visvas tthevtanv, Jezu, amchea Taroka! Jezu, Tum eklo amkam bhasaitai sasnnik jivit: bhasavnnen pett´ta visvas!

Tuka amim polleunk nam, tori môg Tuzo kortanv, Jezu, amchea Taroka! Jezu, Tum chôdd-chôdd boro sogllo môg Tuka favo: amchem sukh Tujea mogan! |

We have not seen You (1 Pet 1, 8)[4]

We have not seen You, but our faith is in You, Jesus our Saviour! Jesus, precious words of Yours of eternal life: to whom can we go:

We have not seen You, but we place our faith in You, Jesus, our Saviour! Jesus, You are the only one for us You destine for us eternal life: This command raises hope! We have not seen You, and yet we love You, Jesus, our Saviour! Jesus, You are so good You deserve all our love our happiness is in Your love! |

[2] See http://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/04/30/mary-to-mira-just-a-sound-away/

[3] Popular wisdom enshrined in the hymn “Dev amkam zai”, Gaionancho Jhelo, hymn F 3.

[4] Type: Hymn. Source: Gaionacho Jhelo, 1995 edition, R-40. Lyrics: Vasco do Rego, S.J. Music: Olavo V. Pereira. Publisher: Gõychi Sevadhormik Somoti (Pastoral Institute), Old Goa, Goa 403 402. Translated by: Alfred Noronha, Pandavaddo, Chorão, Goa 403 102. August 2005.

Breve história do Tiatr

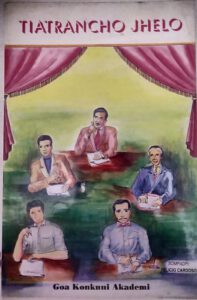

Excerto (ligeiramente editado) do prefácio de Felício Cardoso à obra intitulada Tiatrancho Jhelo (Goa: Goa Konknni Akademi, 1996). O livro, cujo título significa “Grinalda de Teatros”, por ele editado, foi publicado pela Academia da Língua Concani, de Goa, a assinalar o primeiro centenário do teatro da língua concani.

Excerto (ligeiramente editado) do prefácio de Felício Cardoso à obra intitulada Tiatrancho Jhelo (Goa: Goa Konknni Akademi, 1996). O livro, cujo título significa “Grinalda de Teatros”, por ele editado, foi publicado pela Academia da Língua Concani, de Goa, a assinalar o primeiro centenário do teatro da língua concani.

Felício Cardoso (1932–2004), natural da aldeia de Seraulim, Goa, foi um jornalista que destacou o uso e o progresso da língua concani na segunda metade do século XX. O seu tablóide Sot fundiu-se com o diário de língua portuguesa A Vida, formando um novo diário de língua concani Divtti, do qual ele era director associado. Mais tarde dirigiu o diário Novem Goem. Traduziu alguns escritores russos, resumiu a história de Aladdin e os Quarenta Ladrões em concani, publicou Tufan, uma colecção de seus contos, e editou Tiatrancho Jhelo. Faleceu num acidente de viação junto com o amigo e companheiro de trabalho Pe. Freddy da Costa.

-o-o-o-

O vocábulo Tiatr[i] advém da palavra portuguesa “Teatro”, que significa drama, casa de cinema, e ainda, colectânea das obras dramáticas de um escritor. Ora, em concani, essa palavra adquiriu um sentido especial: drama, encenação, divertimento, canção, pequenas representações (farsas). Tudo isso, quando apresentado no palco, leva o nome de tiatr.

Foram artistas da comunidade católica goesa que deram início ao tiatr, na cidade de Bombaim, em abril de 1892. Uns sócios goeses do Instituto Luso-Indiano nessa metrópole costumavam apresentar peças teatrais, em português ou inglês, no Gaiety Theatre (ora, Capitol Cinema) e no Cowasji Hall, em Dhobitalao, uma ou duas vezes ao ano, assistindo a elas só gente ilustrada. Às vezes, os goeses com menos ou sem instrução, participavam no zagor[ii]. Em geral, esta apresentação era de baixa qualidade, e obscena, sendo por isso motivo de vexame à comunidade goesa.

Lá pelo ano de 1890, a Italian Opera Company apresentava uma peça em Bombaim, onde nessa altura viera Lucasinho Ribeiro[iii], de Assagão. Este, mal que viu essa ópera, sentiu desabrochar em si a arte teatral. Por intermédio de um goês, arranjou forma de entrar nessa trupe, em que ficaria encarregado só de manobrar a cortina, pois outra coisa não sabia, sendo por isso até mal pago. Depois de ter viajado com essa equipa às cidades de Puna, Madrasta, Simla e Calcutá, demitiu-se quando a companhia estava prestes a viajar para a Birmânia.

Ora, Ribeiro voltou a Bombaim com as velhas roupas de veludo que adquirira a essa companhia teatral, tencionando apresentar uma ópera em concani. Travou conhecimento com Caetaninho Fernandes[iv], de Taleigão, e andaram os dois à procura de moços que se dispusessem a actuar no tiatr. Não encontraram, porém, qualquer interessado; ninguém se dispunha a subir ao palco, receando que o tiatr não passasse de mero zagor. Ribeiro ficou triste por não poder levar avante o seu plano, dadas as dificuldades.

Um dia, quando menos esperava, Caetaninho encontrou-se com João Agostinho Fernandes,[v] de Margão. Contou-lhe o seu plano a respeito do tiatr. Por sua vez, Agostinho visitou Ribeiro. Depois, os três visitaram os kudd[vi], onde contavam angariar jovens para o projecto do tiatr. A muito custo, acharam dois rapazes, um deles,[vii] Augustinho Mascarenhas, natural do bairro Mungul, de Margão.

Ribeiro precisava de 9 artistas para a encenação da sua ópera; porém, eles eram só cinco. Decidindo então que cada um desempenharia dois papéis, puseram-se a ensaiar a peça todas as tardes. Em fevereiro de 1892, esses cinco jovens entusiastas, sob a direcção de Lucasinho Ribeiro, lançavam as bases do teatro em concani. Em 17 (?) de abril desse ano, no New Alfred Theatre, foi ao palco o primeiro tiatr, muito parecido com ópera, intitulado “Italian Bhurgo” (‘Moço Italiano’).[viii]

Dada a ligação íntima que a comunidade cristã de Goa tinha com os portugueses, estes tinham grande ascendente cultural sobre os goeses. Também se nota a influência da cultura ocidental sobre o teatro da língua concani. A maioria das cantaram (canções) do tiatr são baseadas em músicas ocidentais.

Em poucos anos, surgiram mais companhias teatrais na cidade de Bombaim, entre outras, The Goa Portuguese Dramatic Company; Ribeiro & D’Cruz Opera Co.; Lusitan; Dona Amélia; Dom Carlos; Douglas Comic Opera; Karschiwalla’s Delectable Co.; Goa Union; Lazarus Comic Opera; Goa National; Union Jack: todas elas muito populares.

O tiatr tradicional – seja ele de divertimento; social; religioso, ou outro– compõe-se de 7 partes, conhecidas como porde (cortinas). No começo do tiatr, e quando cai a cortina, são interpretadas três ou mais canções. Elas não têm relação alguma com o tema do tiatr; e, sejam solos, duetos, trios ou quartetos, têm o condão de fazer rir ou chorar, de corrigir as depravações sociais, apontando às falhas de corrupção ministerial e de astúcia política, e de repreender os maus. Em toda essa mescla, o tiatr tem graça e sobressai.

Dantes, o tiatr constava de 21 ou mais canções. Realizava-se à noite, e terminava na madrugada seguinte. Hoje, porém, tem havido muitas alterações. Está reduzido o número de cortinas e de canções.

Actualmente, é radiodifundida uma variante do tiatr que se chama khell-tiatr ou “non-stop show” (teatro popular, ora conhecido como “espectáculo ininterrupto”).

O tiatr, apesar de ter sido emanado do zagor, ocupa um lugar ímpar na Índia. É mais distinto do que o teatro em diversas línguas indianas. Não se assemelha a outros géneros dramáticos, ou seja, ao khell doxavtari ou o tamasha do Maharashtra; não é igual ao Bhovaia do Guzerate ou às canções populares do Karnataka; não se assemelha ao latra ou zatra da Bengala, ao Ramlila ou Roslila do Norte da Índia, ao nouttonki do Punjabe, ou ao kathakali do Kerala.

A maioria das peças teatrais não estão em letra de forma. Estão a rarear os seus manuscritos, sendo pouquíssimas as excepções. Estão impressos os dramas de João Agostinho Fernandes e de uns outros dramaturgos. De entre os nossos contemporâneos, artistas amadores como Tomazinho Cardoso, o padre Planton Faria, o padre Freddy J. da Costa e César D’Mello, têm vindo a publicar as suas peças teatrais.[ix]

Nos últimos 50 anos, foram encenados esses tiatr em Goa, em Bombaim e em outros lugares. Estão sempre cheios do tempero da sensação. No tiatr são tecidos o enredo, o diálogo, o entretenimento, o amor, a ira, o suspense e outros elementos.

Nos primeiros cem anos do teatro concani nasceram e morreram milhares de artistas de renome. Saíram da sua pena e foram levados ao palco inumeráveis tiatr que também merecem ser publicados. Caso contrário, esta nossa arte dramática entrará no ocaso.

-o-o-o-

[i] Tiatr é a forma tanto singular como plural desse substantivo em concani.

[ii] Zagor, teatro popular da comunidade hindu de Goa.

[iii] A certa altura, Constâncio Lucasinho Caridade Ribeiro (1863-1928) separou-se dos outros três, fundando a Ribeiro & D’Cruz Opera Company. Diz João Agostinho Fernandes, no seu artigo intitulado “Theatrancho Bhangaracho Jubileo”, publicado no Avé-Maria, semanário bombaense, em 25 de novembro de 1943, que foi Ribeiro o pioneiro da arte do tiatr.

[iv] Era empregado do bissemanário Bombay Gazette.

[v] João Agostinho Fernandes (1871-1947) foi empregado comercial e a sua (primeira) esposa, Regina, a primeira mulher goesa que subiu ao palco. Escreveu 27 peças teatrais em concani. Popularmente conhecido como ‘Pai Tiatrist’ (Pai dos Dramaturgos), foi baptisado com o seu nome e epíteto a sala de concertos Ravindra Bhavan, em Margão.

[vi] Kudd, aposento(s), que aqui se referem aos clubes, estabelecidos por associações goesas em Bombaim, e nos quais goeses de estratos mais humildes se aloja(va)m, transitoria ou demoradamente, quando em serviço nessa metrópole.

[vii] O quinto chamava-se Fransquinho Fernandes (Cf. John Gomes (Kokoy), Tiatr Palkhache Khambe, Goa: Queeny Productions and Publications, 2010, p. 5).

[viii] Sob a égide de The Goa Portuguese Dramatic Company, formada em 1892 (Cf. André Rafael Fernandes, When the Curtains Rise, Goa: Tiatr Academy of Goa/Goa 1556, p. 8)

[ix] No referido Tiatrancho Jhelo figuram os seguintes tiatrist (dramaturgos): no primeiro volume, C. Álvares (“Kedna udetolo to dis”, ‘Quando raiará esse dia?’); Remmie J. Colaço (“Atancho Temp”, ‘Os tempos actuais’); John Claro Fernandes (“23 Vorsam”, ’23 anos’); Prem Kumar (“Vauraddi”, ‘Operários’); e M. Boyer (“Ekuch Rosto”, ‘Única Via’); e no segundo, João Agostinho Fernandes (“Kunnbi Jaki”, ‘O curumbim Jaki’); José Pascoal Fernandes, vulgo J. P. Souzalin (“Sat Dukhi”, ‘Sete dores’); Aleixinho Fernandes, vulgo Aleixinho de Candolim (“Amchi xetachi panvddi”, ‘O leilão da nossa várzea’); A. Souza Ferrão (“Gouio Put”, ‘O filho maluco’); Caetano Manuel Pereira, vulgo Kim Boxer (“Somzonnent chuk zali”, ‘Um mal-entendido’). O terceiro e último volume, dedicado ao khell-tiatr, teatro popular, não chegou a ser publicado.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 22, maio-junho 2023)

“The Lord is my Shepherd”

In our somewhat directionless world, isn’t it reassuring to hear our inner voice say, “The Lord is my shepherd, there is nothing I shall want”? These verses from the David’s Psalm echo through the three Readings of today; not only were they said by Jesus in His own lifetime, Peter repeats them endlessly after the Resurrection.

After the Resurrection, it was important to catechise. We see once again, in the First Reading (Acts 2: 14, 36-41), how the first Apostle reproached people for putting Jesus to death and urged them to repent. The reward for their repentance would be to receive “the gift of the Holy Spirit”. The pardon of our sins, the gift of the Holy Spirit and the New Covenant are the fulfilment of messianic promises. They are open to anyone who accepts the Word of God and transforms their life. And what a privilege, as St Peter puts it, “The promise is to you and to your children and to all that are far off, every one whom the Lord our God calls to Him.”

Again, in his First Letter, part of which forms the Second Reading of today (1 Pet 2: 20-25), St Peter conscientizes the people. He talks about how Jesus who is at once our Shepherd and Paschal Lamb. By His voluntary Sacrifice, He showed us the way from death to life eternal. St Peter therefore invites us to suffer, as Jesus did, in the midst of life’s difficulties, which include misunderstandings, calumnies, accusations and persecutions, all of which Christians suffer for being a stumbling block and rock of offence to the world.

Through it all, we learn from the Gospel (Jn 10: 1-10), we have nothing to worry, for Jesus the Good Shepherd is always by our side. He knows His Father in Heaven very intimately, and know us too with the same intimacy. He thus becomes “the door” to Heaven, the Mediator par excellence to our Father in Heaven. And His warning against false teachers and doctors – “thieves and robbers” all – is valid for all times, especially our own. He is the Way, the Truth and the Life; He is our only salvation. He is the door; anyone who enters by Him alone will be saved.

This Sunday, then, is rightly known as “Good Shepherd Sunday”. May we trust only Jesus to be our Shepherd through life; through Him alone can we have life, and life in abundance. Above all, may our Pope, our bishops and priests be good shepherds, taking the lay faithful always to the right pasture.

Mary to Mira: just a sound away?

The article titled ‘Milagris and Lairai: fostering the bond of divine unity’, by historian Dr Sushila Sawant Mendes (Herald, 23 April 2023)[1] has added to the myth rather than clarified it. One would expect to be enlightened on the origin of the statue of Our Lady of Miracles (also Milagr Saibinn, in Konkani), or the story of the Seven Sisters, or even be favoured with a sociological or anthropological explanation; but that was not to be. At any rate, as a lay reader, I wish to raise a few issues about its interface with Catholic practices in Goan society.

To start with, the loose use of the term ‘divine’ with reference to Our Lady leads to considerable confusion. Mary, the mother of Jesus, is not a goddess but a human being, whereas Lairai, shrouded in legend, is one of the seven sister goddesses to the Hindus. Why link a historical personage to a mythological septet? It is therefore gratuitous to put Lairai on a par with Milagr Saibinn.

Quite understandably, the article is riddled with expressions like ‘It is believed’ and ‘Legend has it’. But saying that “Milagris Saibin is believed to be the deity Mirabai, a sister of Goddess Lairai” begs the question: believed by whom? Is there a formal acceptance of the belief, or is it a belief held by an amorphous mass of individuals that offer flowers or pour oil on the statue? The latter practice is, perhaps, of recent origin and the only one of its kind in Goa.

From the Catholic perspective, the story is not Mariological. And stating that “There is a tradition to offer oil to the Milagris Saibin from the Shirigao Devasthan and mogra flowers are offered to Lairai Devi from the St Jerome Church in Mapusa” is not in keeping with any official Catholic tradition in Goa. So, the onus of showing the origin of such a protocol, if any, lies on our historian-writer.

That the purported institutional exchange is a no-no even from the Hindu side was confirmed by iconographer Dr Rohit R. Phalgaonkar, who has researched the issue.[2] No doubt, Mirabai was one of the seven sisters from folklore, but after her abode, Mapusa (not Mayem, as stated in the article), converted to the Catholic faith, way back in the sixteenth century, the temple authorities in Shirigao (and elsewhere) stopped mentioning Mirabai in the traditional invocations. In fact, “none of the sister temples make a reference to Milagris in their official records and in the religious duties or rituals that they perform at the festival. She is not an icon of the Hindus; she is a Christian icon," he added.[3]

Therefore, to say that Milagr Saibinn has taken the place of Mirabai is not plausible; and Dr Phalgaonkar wonders why Milagr Saibinn would have a link with Lairai alone and not with the other sisters! This only goes to prove that, if the issue is not handled with academic rigour, it can be grist to the myth-making mill even in our day and age.

Not surprisingly, there is a dash of magic realism, which helps bring the story alive: “… it is believed that the two sisters visited each other on the day of their respective festivals.” And risking repetition, the writer says, “Folklore tells us that Milagris Saibin would send flowers as a gift to her sister, Goddess Lairai, during the zatra. Lairai would send in turn oil for her sister’s feast.” That is to say, while earlier on in the article, the two institutions were given credit for the magical feat, now it is Milagr Saibinn and Lairai Devi themselves who show how they care for each other! Can scientific writing sacrifice accuracy at the altar of artistic licence?

With the theme of unity and a sense of disclosure ever present, the writer is keen to show that Goa is an oasis of intercommunal peace; and she bends over backwards to prove her point. That “every generation of the people of Assolna, Velim and Cuncolim have grown up with the belief that the Goddess Shantadurga of Fatorpa is the sister of Saude Saibin of the Church of Our Lady of Health in Cuncolim” is either an exaggeration or it speaks poorly of the catechesis received by the Catholics of those villages (AVC).

That is a facile generalisation, which, read alongside the sentences now in parentheses (“The festival of the Sontrios in Cuncolim and the devotional visits of the Catholics to this temple is a graphic representation of this undying belief. Tomorrow is both the feast of Milagres Saibin at Mapusa and the Shree Devi Lairai Zatra at Shirigao, both to be celebrated on the same day after thirteen years, on April 24 this year”) summarily puts Catholics across the length and breadth of Goa under the sontri or umbrella of a syncretic religion.

The article runs high on emotions. After referring to Lairai’s many sisters, the writer states: “Since all are still sisters, it is understood that people worship at either their temples or churches. It is an emotional explanation of how Goans are still one people with one culture even if, on the surface, they are divided.” Is the writer implying that Goans randomly visit places of worship – and does that effectively prove that they are “still one people with one culture”?

It is undeniable that the Indian Constitution allows freedom of religion and worship, but does that lead to licence? We get the impression that Goan Catholics and Hindus have no sense of belongingness and loyalty: they run with the hare and hunt with the hounds. Especially Catholics, followers of a monotheistic religion, to insinuate that they worship indiscriminately is a slur on their character.

We are catapulted into the next stage of mythification, on reading the story of Lairai fighting with her brother Khetko. When the writer says that “The ceremonies [at Shirigao] culminate when devotees walk through fire as acts of repentance by the two sisters who had mistreated their brother”, it is not clear which sister fought alongside Lairai and has been paying for it till date. Contextually, or say, in the writer’s variant of the myth, would it be a reference to Mary who has supposedly replaced Mirabai? The fact of the matter is that Mary had no brother and her world was one of meekness and peace.

Is it only a step from Mary to Mira? Or so it is made to appear – just a transposition of syllables! Whether or not “Goans worshipped the Mother Goddess in a number of forms even before the Portuguese arrived”, it is improper to say that “with the coming of the Portuguese, the Virgin Mary was introduced in her various versions”, for the Blessed Virgin Mary has no “versions” but only invocations and titles. Add to it the statement that the “Goans thus turned from one form of Mother Goddess to worship another”, and you have a gross oversimplification of the historical situation! And needless to say, to examine the claim that “many temples dedicated to the Mother Goddess were rebuilt as churches dedicated to Our Lady” would require a thorough historical approach.

To conclude: Considering that no society is devoid of myths, or even completely homogeneous in its myths, we can make allowances for the article’s ‘mythical reasoning’. India is a land abounding in myths and legends; we usually take them in our stride, considering that they have come down from a remote past over which we have no control.

Accordingly, living as we do in a secular democracy striving towards peaceful coexistence, the writer has ended up secularising the myth, of course, cherishing a well-founded hope for “a strong bond of unity”. But whereas this unity is desirable and even achievable at the social level, to endeavour to merge institutional identities, unite heterogeneous beliefs, and mix up religious doctrines is unacceptable.

Can we guard against processes leading to new myths? It is the bounden duty of academics to get to the bottom of it lest peace and unity become a myth.

Banner: https://gogoanow.com/milagres-feast-celebrated-st-jeromes-church/

[2] Cf. his lecture titled ‘Seven Sister Goddesses’ at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BDsQFx4jpII

[3] Interview with Dr Rohit R. Phalgaonkar, 28/29.4.2023.

The Challenge of Faith

Today’s Gospel, taken from St Luke (24: 13-35), is about what happened on the evening of the Resurrection and how the eyes of two disciples were kept from recognising Jesus who had just then joined them on the road to Emmaus. Jesus feigned ignorance of the things that had happened in those momentous days. Rather, He heard what they had thought of Him: that He was a prophet expected to redeem Israel, and now His body was reported missing.

Were they feeling it was all over now? Just then, the fellow traveller lamented their foolishness and how they were “slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken.” But none of that hurt their self-esteem; they even invited the stranger to stay the night with them. And it was there at the table – when He took the bread and broke it – that their eyes saw Jesus; but he had meanwhile vanished out of sight.

What about us, traditional Catholics? We who have been with the Lord all these years, do we know Him up close and personal, or do we just take Him for granted? Do we recognise His presence in our midst, do we discern His signs; or does life go on as though He does not exist? Shouldn’t the Resurrection alone have vindicated Christ, strengthened our faith and fired us with zeal to let the world know that He alone is God? Historically, others who claimed to be prophets, or maybe even God, have died, and we have not seen even as much as a shadow of their former selves.

Moreover, the signs, prodigies or miracles that Jesus wrought during his public life and the marvels that we have been privileged to see down the ages are proof enough that the Church is divine. Jesus still walks the pilgrim path with us; He is with us on our road to Emmaus, a road fraught with difficulties and doubts. Jesus shares in our miseries and also brightens our path – a mystery we can discern only with eyes of faith.

St Peter, who is the focus of the first two readings, drives home the same point. He is all out to proclaim his Master, who, alas, he had thrice denied, but His rising from the dead has now clinched his faith. The First Reading (Acts 2: 14, 22-33) is a synopsis of Peter’s first testimony about Jesus to the eleven, after he received the gift of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

Here is Peter, transformed by the Resurrection! There is a spring in his step and new zeal in his voice. He feels emboldened to speak not only by what his ears had earlier heard, but by what his eyes have now seen: the Risen Lord! He conscientizes the people; he even indicts them for killing the Messiah. Needless to say, God who is always in control, had let it happen “according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God” and now “God raised Him up, having loosed the pangs of death, because it was not possible for Him to be held by it.”

Peter also reminds the people that it had been prophesied by David that God would “not let the Holy One see corruption”. The first Apostle’s message speaks of everlasting life as prophesied by the sweet psalmist of Israel and as fulfilled in the Paschal mystery. He is proud and confident that this faith is not abstract but based on a real happening: the Resurrection. Nonetheless, as a final test of his faith, he who became the first Pope, ordained by Christ Himself, would die an inverted crucifixion in the gardens of Nero.

In the Second Reading (1 Pet 1: 17-21), we see the same Apostle: he had struck the High Priest’s servant Malchus with a sword in the Garden of Gethsemane, and now strikes while the iron is hot. Despite the tense and volatile situation in Jerusalem, Peter does not mince words when he speaks about his and our Lord and Master. His appeal to the faithful to conduct themselves “with fear” must to be understood as holy fear of God the Father, not of man. He stresses that Jesus is the Paschal Lamb who has sacrificed His life for the new humanity. “Through Him you have confidence in God, who raised Him from the dead and gave Him glory, so that your faith and hope are in God,” emphasises Peter.

Finally, we might wonder if a fisherman like Peter was ever capable of writing such profound exhortations. Most likely, his secretary, Sylvan or Silas, edited his letters, yet there is no denying that they are divinely inspired pieces of writing. Similarly, the fact that Our Lord chose poor Peter to lead the Church may baffle the worldly wise. But, then, God wants from us not our wisdom but our faith. A sure way of strengthening this is by becoming fools for Christ, and, like Peter, a rock upon which Christ can build His Church. Dare we accept the challenge of faith that the fisherman once accepted?

Banner: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/altobello-melone-the-road-to-emmaus

Journeying from doubt to belief

Would you believe, the apostles were caught off-guard by the Resurrection! They huddled together in fear, when they should have been rejoicing and shouting from the rooftops! Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, this looks like an obvious point. But the fact is that, although at the Passover Meal Jesus had foretold His return, Resurrexit probably seemed just a word… And let’s face it, what does it mean to us today? Does the Resurrection still have breaking-news effect in our lives?

The world had never seen a resurrection before. No doubt, Jesus had raised three from the dead, but that did not ring a bell in those men of little faith! So, it was not the apostles, but Mary of Magdala who was privileged to first see the Risen Lord. Unable to contain herself, she rushed to break the news to Peter and John, but they simply shook their heads in disbelief. Meanwhile, Jesus appeared to two other Marys and Salome; and in the evening to two disciples journeying to Emmaus. When this duo hurried back to Jerusalem, they found the apostles gathered, all bewildered, in the Cenacle.

According to St John (20: 19-31), the doors being shut where the disciples were gathered for fear of the Jews, Jesus came in and stood among them, saying, ‘Peace be with you’. He had defied the laws of time and space, which probably caused them even more fear. But then, to set all their doubts at rest, He showed them His hands and His side. He bid them to receive the Holy Spirit, and authorised them to forgive and to preach in His Name. This day soon became “the Lord’s Day”, replacing the Sabbath as the day of creation, the Mosaic law and the Pasch; it symbolised a new creation, a new alliance and a new and definitive Pasch. The Gospel account may not be exhaustive, but there is no doubt as to the Church on the horizon.

However, the going was not smooth as it might seem. The Twin has gone down in history as the ‘doubting Thomas’ (St John is the only evangelist to refer to the episode); still, we must not hold it against him, for by the depth of his love he believed, when he met the Lord a week later; by the strength of his bond, he cried, “My Lord and my God”; and by the power of his commitment, he went on an apostolic mission to India. What a lesson for us who doubt – and remain in doubt; ask questions – and seldom seek the right answers! In our jet age, while we pretend to eloquently reason out, we fail to see that faith alone can touch infinity and set us free.

So many holy traditions can be traced back to that Day of the Lord: the peace greeting; the receiving of the Holy Spirit; the sacrament of confession; and the duty to evangelize. Lest these meaningful commands turn into meaningless rituals, it is of the essence to remember that our acts must be soaked in faith. The Lord expects nothing short of a leap of faith, for “blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe.”

That is what happened when thousands converted and led good lives in the wake of the Resurrection. The First Reading (Acts 2: 42-47) tells us that the neo-converts “devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers.” By having “all things in common”, they sowed the seed of religious communities; by selling or distributing their possessions, they introduced charitable living. None of that is an injunction against private property, for they did so “as any had need”. But one thing is sure: by refraining from accumulating wealth, they emphasised that our real treasure lies in Heaven. Thus, the neo-converts lived in the joy of the Lord and felt blessed.

That is yet another lesson for us traditional and pedigreed Catholics to imbibe. It is a pity that sometimes we distance ourselves from the Messiah, if not reject Him wholesale. By shameful acts of omission and commission, we put him to a shameful death over and over again. If the Resurrection will not convince us of the divinity of Our Lord, nothing else will. In fact, after He rose from the dead, His divinity was even more pronounced than his humanity.

Thankfully, the Second Reading (1 Pet 1: 3-9) renews our hope. It teaches us that “by His great mercy, we have been born anew to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, and to an inheritance which is imperishable, undefiled, and unfading, kept in Heaven for you.” We may suffer a little while on earth, but that suffering is a purging. We must, through it all, continue to praise and thank God for our Christian vocation.

Finally, Christ being the reason of our being, we must dispel the darkness of doubt and soak in the light of belief. In fact, the Gospel account was written precisely “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in His Name” (Jn 20: 30-31). It promises not a naïve and selfish joy of the flesh but a deep and self-giving joy of the spirit, simple and life-giving. This is a marvellous hope that we can all nurture as we renew our Christian life; it is a most wonderful way of being Church.

Banner: https://reclaimingourchildren.typepad.com

Why Easter is the bedrock of our faith!

It's thanks to Easter that we are Christians. Whereas the joyful birth of Jesus contained a promise, this was fulfilled through His sorrowful Death and glorious Resurrection. This unparalleled event was the ultimate answer to those who had rejected His luminous earthly passage abounding in wise teachings and unprecedented miracles. He who had come to complete the Jewish religion thus founded a new and sublime religion – Christianity – that would be open to the peoples of the world.

The panoply of readings of the Easter Vigil and Mass tells us the story of the redemption of the world. The seven readings[1] from the Old Testament and two from the New Testament are “chosen and structured to lead the worshipping assembly into a deep contemplation of the mystery of salvation history—from the beginning of time, when God created the world in all its wonder, to this moment of the Church gathered in prayer, to the end of time when all things will be brought to perfection once again in God's love.”[2] In other words, the readings tell of the Redeemer about whom the prophets had long foretold.

The Easter Sunday (morning and evening) Mass offers a different set of Readings, of which the Second Reading and the Gospel have internal choices.[3]

Starting with the Gospel: obviously, it is about the Resurrection! If we read the four Evangelists, we cannot fail to see the multiple differences in their accounts. However, the disparity lies only in the secondary details: while St John (in all probability) wrote a first-hand account, the rest of the Evangelists wrote theirs based on eyewitnesses. Most importantly, none are at variance on the fundamental issue: that the tomb was found without the Lord early on Sunday morning. It was not a desecration; it was undoubtedly the Resurrection!

In fact, those variations only go to show that the Resurrection accounts were not tailored; they were written at different times, between circa AD 66 and 110, in this order: Mark (AD 66-70), Matthew and Luke (AD 85-90), and John (AD 90-110). And even if they had never been written, there would still have been other evidence of the stunning event. St Luke’s Acts of the Apostles was put together between AD 70-90, and Paul’s letters between AD 50-58. Clearly, these latter are the earliest extant texts about the Resurrection, predating the first of the Gospels by over a decade. Would God the Father have allowed the most important event of all of history to go unrecorded?

Very pertinently, the first two Readings are taken from the accounts of those two travelling companions, Luke and Paul, respectively. The text of the Acts (10: 34a, 37-43) refers to the by-now fiery St Peter chastising those who put Jesus to death. “But God raised Him on the third day,” he states, “and made Him manifest, not to all the people but to us, who were chosen by God and witnesses, who ate and drank with Him after He rose from the dead.” Faithful to the Divine Master’s command, the future First Pope testifies: “To Him all the prophets bear witness that every one who believes in Him receives forgiveness of sins through His Name.”

Even more clinching is St Paul’s testimony relating to the Resurrection. Here is one of Christ’s worst persecutors, whose conversion history is so well known that it can be dispensed with here. In today’s Second Reading (Col 3: 1-4), he most convincedly points to Christ “seated at the right hand of God”, and invites us to set our minds on things that are on high. It is the same Paul who famously said, “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins.” (Cor 15: 17) He championed Christ’s cause – His physical Resurrection – which prompted Roman emperor Nero to order his beheading.

Let alone dying like Paul, had we only believed more firmly in the Resurrection and spoken more ardently about this turning point in the history of humankind, by now there would have been only Christian apologists walking the earth and no apologetic Christians in sight! After two thousand years of Christianity, can we say we have done enough?

Let us therefore resolve to rise above our frailties – to rise with Christ and live with Him forevermore, with Him who is indeed the Resurrection and the Life!

[1] The Vigil readings for all Year cycles are as follows: Gen 1: 1-2, 2; Gen 22: 1-18; Ex 14: 15-15, 1; Is 54: 5-14; Is 55: 1-11; Bar 3: 9-15, 32 – 1, 4; Ezek 36: 16-28; and at the Mass thereafter: Rom 6: 3-11 [Year A]; Mk 16: 1-7 [Year B], Lk 24: 1-12 [Year C]

[2] http://pastoralliturgy.org/resources/1301OurStoryOfSalvation.php#:~:text=The%20nine%20readings%20of%20the,to%20this%20moment%20of%20the

[3] The Second Reading can be either from Colossians (3: 1-4) or Corinthians (5: 6-8). And while the first choice of Gospel text is from St John (20: 1-9), one may alternatively take any one of the Gospel texts of the Easter Vigil Mass: Mt 28: 1-10 marked for Year A; Mk 16: 1-7, for Year B; or Lk 24: 1-12, for Year C. The Lectionary also specifies that at evening Mass, Gospel of the Third Sunday of Easter, Year A, may be read.

Banner: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/fra-angelico-christ-glorified-in-the-court-of-heaven

The Suffering Servant

Today is Palm Sunday. The day begins with the blessing of palms with holy water outside the church building. The Gospel read here is from St Matthew (21: 1-11) in Year A, St Mark (11: 1-10) or St John (12: 12-16) in Year B, and St Luke (19: 28-40) in Year C. The priest then leads the congregation in a festive procession into the church, celebrating Our Lord’s messianic entry into Jerusalem.

However, at the Mass soon thereafter, the mood changes from joyful to sombre, marking the beginning of the Holy Week. While the first two Readings and the psalm – Is 50: 4-7; Ps 21: 8-9, 17, 18a, 19-20, 23-24; Phil 2: 6-11 – remain the same for cycles A, B and C, the Gospel changes from year to year, highlighting the three Synoptics: St Matthew (26: 14-27, 66), St Mark (14: 1-15, 47), and St Luke (22: 14-23, 56), respectively. They account for happenings going from the Last Supper up to the Death of Jesus.

St John is thus the only evangelist whose Gospel is not read at this Mass. The Beloved Disciple – who offers a unique perspective on the Divine Master, more theological and mystical – is very especially reserved for Maundy Thursday (Jn 13: 1-15) and Good Friday (Jn 18: 1-19, 42), besides two weekday readings. While the Gospel on Thursday focusses on the Last Supper, on Friday we hear a Passion narrative that begins with Gethsemane and ends with Our Lord’s Death on the Cross.

Coming now to the three Readings of today: in the First Reading (Is 50: 4-7), who is Isaiah talking about? He could well be referring to himself or to an archetypal prophet, for all prophets suffered persecution. Better still, Isaiah could be referring to the One who was to come: Jesus the Messiah! Jesus, the Servant of God, was an unparalleled Master, who was nonetheless obedient to the will of His Father in Heaven. Jesus is the model Servant who trusts in God and prevails over His enemies.

That the life of Jesus was a fulfilment of the prophecies of yore becomes clear in the richly textured Gospel passage (Mt 26: 14-27, 66) on the Passion of Christ. The text comprises Jesus’ scandalous betrayal by Judas Iscariot, as foretold at the memorable Passover meal; His moments of intense prayer on the Mount of Olives; His acts of extreme goodness even when His soul was sorrowful to death; His unlawful arrest and summary trial by the high priest; His shameful denial thrice over by Peter; His monstrous condemnation by Pilate; His distressful way to Calvary; His crucifixion, death, and burial.

St Paul in the Second Reading (Phil 2: 6-11) points to the humility of Jesus. He who was fully divine willingly became fully human; He who was “in the form of God did not count equality with God (…) but emptied Himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.” His total obedience led to His humiliation, but which in turn engendered His exaltation. God gave him a name “which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow (…) and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.”

None who have carefully listened to the three readings of today will remain unmoved. May this Holy Week cause us to reflect on the human condition and our divine commitment. Some of Our Lord’s sufferings are today inflicted upon His Living Body, the Church; some of them are perpetrated by us from within. God might sometimes allow our humiliation and suffering, but never our annihilation; our faith, hope and trust in God’s protection will ensure our final exaltation. May the story of Jesus Christ, the Suffering Servant, and His supreme love for humanity bring about our conversion and sanctification.

Don Bosco’s: after a kind of absence

Way back in the 1970s, how did our parents choose from half a dozen schools in Panjim? Don Bosco’s must have been the most obvious choice, given its infrastructure and proven track record; it was a dream school to many from far and wide and all stations in life.

Don Bosco’s had by far the largest educational campus in the then union territory of Goa. The main, (then) two-storeyed edifice, spacious, bright and airy, housed the school, the priests’ residence and the boys’ boarding (especially during the Persian Gulf boom). The building was cut across by a passage leading to a new shrine dedicated to Our Lady of Fatima, where Mass for the students, on First Fridays, was a spiritual feast. Elsewhere on the campus, sports facilities were among the best at the time. And to wrap it all up, the school motto, Virtus et Scientia, pointed to a holistic education and recipe for happiness.

But what man is happy? Only "he who has a healthy body, a resourceful mind and a docile nature," says a philosopher. To our good fortune, that was quite the staple diet we students grew up on; it let Bosco boys stand out not only in academics, but also in intra- and extra-mural pursuits that included music (remember the brass band?); sports (particularly football, basketball and hockey); elocution, debate, and so on. ‘All-rounder’ was a buzzword, in the run-up to the examination of life.

Needless to say, school was no cakewalk; sometimes there was waywardness, dejection and frustration along the way. But, through it all, the aspirations of the Salesian brotherhood shone bright, distilled into that martial anthem whose lyrics and melody render me nostalgic before they finally pep me up:

We the proud Don Bosco boys

brave Don Bosco brotherhood.

Nursing in our heart the joys

Of true knowledge and the good.

Forward march with equal pace

Through our country’s sounding ways

Treading where our fathers trod

In the glorious light of God.

We who are the happy band

Will not shrink from sweat and strife.

In the service of our land

For a brighter cleaner life.

We will toil till out of gloom

Day shall dawn and deserts bloom.

And our country’s blessed soil

Shall be green and gold for God.

Don Bosco’s was clearly ahead of its time. It had a vibrant ‘Past Pupils Association’. When alumni found it tough to secure proper lodgings in the bustling capital, a hostel was built for the purpose, at a far end of the campus. So much for connectedness. But perhaps even more distinctive was the Oratory, an institution inspired by the founder St John Bosco himself. The Saint of Turin had realised, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, that young minds longed for more than just hard skills – they sought loving kindness!

For long, the Oratory functioned in the desacralized, old Fatima chapel located right in the middle of the vast estate; inscribed on its façade were the words ‘Visitasti Nos’ (You Visited Us, in Italian) commemorating the coming of the Pilgrim Virgin statue there in 1950. The place was a safe haven to a motley crowd that included the less fortunate, poor, and abandoned youth. And even those who did not much fancy the place did feel its magnetic pull at some time or other in their lives!

All things considered, it was a matter of pride to belong to a school where one trained in good citizenship of the church, the country and the world. Catechism and Moral Science classes virtually set the tone. And who can ever forget ‘Don Bosco’s Seven Tips to Boys’ bulleted in the school handbook? They always bear repeating:

- Do not waste time.

- Do not offend God.

- Do not overeat before studying.

- Avoid bad companions as poisonous snakes.

- Choose some studious boys as friends.

- When it’s time to play, get in there and play.

- Do not daydream! Keep your mind on your books when studying.

- Above all, PRAY.

Hopefully, a lot of that wisdom has stayed with the “proud Don Bosco boys” and been passed on to generation-next!

Oh, how all of this seems far back, yet close at hand!... Am I lost in reverie? Be that as it may, our alma mater has her feet firm on the ground; even if at times we have taken her for granted, she, like a doting mother, has been there for us. And whereas her alumni have grown old, she has, thankfully, only grown big! Here I wish to pay homage to my teachers, some of them priests and brothers; and to remember my classmates too: we are now a scattered lot, aren’t we? No wonder it feels like a kind of absence….

On the occasion of the triple Jubilee, I salute the Salesian family for holding on. Don Bosco’s has grown into a splendid oasis amidst a slowly emerging concrete jungle; but then again, weeds of the world must not be allowed to close in on it! Don Bosco’s has come a long way, and the Founder’s spirit must live on: this will be a clincher for twenty-first century parents waiting to choose from more than half a dozen schools in the city!

(First published in the Souvenir Back to School)

(Banner: https://sdbpanjim.org/newsdetails.php?id=1505; Pics 2 and 3, courtesy Eustaquio Santimano, Flicker)