Elephantine Blunder

It is significant that, close on the heels of an elephantine blunder that we have witnessed in our archdiocese, this Sunday’s liturgy of the Word comes down heavily on those who scandalously turn to other gods.

In the First Reading (Ex 32: 7-11, 13-14) God is rightfully angry with His people for forgetting Him Who had delivered them from the slavery of Egypt. Now they worship abominable little gods of their own making.

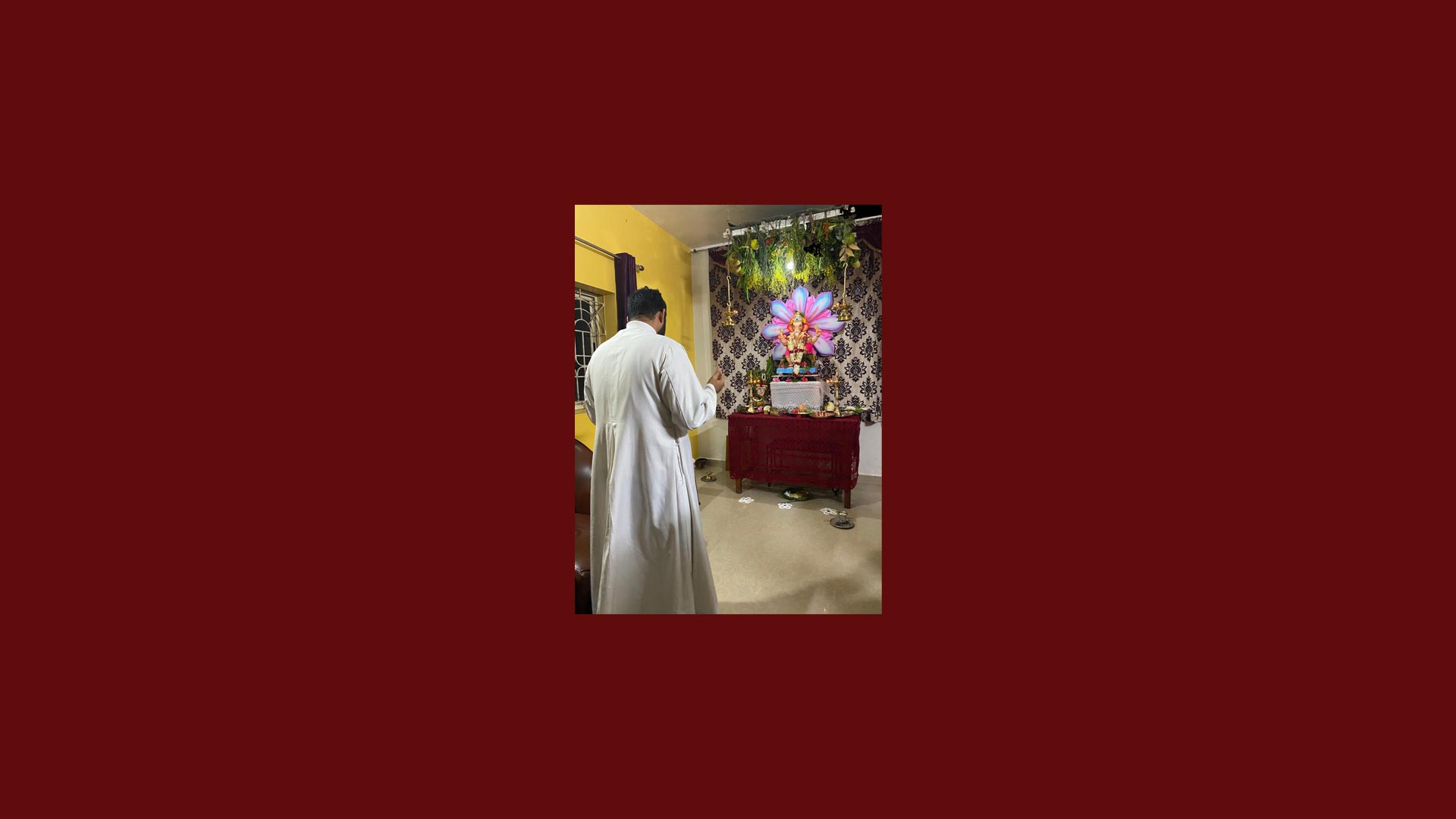

How is this any different from Catholics ‘jumping on the idol worship bandwagon’ [1] in Goa? More than one priest is known to have gone on pilgrimage to Ganesh household shrines. If it was a plain social visit, this priest’s prayer posture absolutely begs an explanation.

What is the rationale behind bowing before idols? It is one thing to build bridges on the social plane, say, by having colleagues from other faiths and enjoying their company at work or in the neighbourhood; it is quite another to be praying before their deities. If this is not a breach of the First Commandment, what is?

The laxity in the practice of our faith seems to be a natural consequence of an ‘inculturation’ gone awry. It has shown us the true colours of the so-called ‘inter-faith dialogue’. And the project is rendered even more sinister by the fact that there is a concerted effort to play to the gallery, at the national and international levels. And playing the game is a clique of fifth columnists that collects funds for a misplaced ‘evangelization’.

That is to say, what we have witnessed in Goa is not an isolated incident; it is not a case of one priest going astray but rather a case of one expressly led astray. It fits the bill.

If we are not to sit in judgement without listening to the other side, it is sincerely hoped that the matter will be clarified by the ecclesiastical authorities in the archdiocese and by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI), of which our Archbishop and newly-appointed Cardinal is the president.

At any rate, we also hope that the teaching of our religious doctrine will stop being fuzzy; that its practice will be truthful and firm, and that we will decidedly stop walking on the razor’s edge.

(This post was first circulated on Whatsapp, Sunday, 11 September 2022)

[1] https://www.churchmilitant.com/news/article/goa-new-cardinal-winks-at-ganesh-idolatry

Crucible of love and mercy

It’s never too much to talk of love and mercy. God is a crucible of love and mercy – celestial material that humans yearn for. And be it between parents and children, husband and wife, neighbours, friends or foes, love and mercy are of the essence; they keep the machine of life oiled and running sweetly.

God the Father, who is the source of all that is good, has set the example. In the First Reading (Ex 32: 7-11, 13-14) God is rightfully angry with His people for forgetting Him Who had delivered them from the slavery of Egypt. Now they worship abominable little gods of their own making.

In the Gospel (Lk 15: 1-32), we read three delightful parables that highlight the extent of God’s love and mercy. The Divine Master’s abiding concern is to reach out to those in need, so He responds to those who fail to appreciate His mingling with sinners. Jesus speaks of the proverbial shepherd going out in search of his lost sheep and of a woman who is in search of a lost coin.

Alternatively, we could look at the lost sheep and the lost coin as entities hoping to be found or saved by their respective owners – in the same way as our spirits thirst for the love of the Father!

Yet, the most heart-warming part of the trilogy on redemption is that parable about the Prodigal Son. It covers a whole gamut of human experiences: if the younger son could be booked for greed, lust, gluttony and sloth, the pharisaic elder one is symbolic of pride, greed, envy and wrath. Between them they have all of the seven deadly sins! And whereas the son is prodigal – extravagant – with his money and possessions, the father is prodigal – overgenerous – with his love and mercy.

Finally, St Paul’s frank testimony (1 Tim 1: 12-17) echoes a common experience. Just as he acted out of ignorance, sometimes we too aren’t careful about how we judge people and situations. We dub parental concern or spousal devotion ‘paranoid’; neighbours’ concern, ‘inquisitiveness’; and friends suddenly become foes for unexplained reasons. In the midst of it all, and much against the evangelical command, we stay put and criticise everyone; we don’t care to lift even a finger to help those in need – maybe for fear of getting it wrong, or simply out of laziness or indifference!

That’s when it will pay to remember that the divine crucible of love and mercy is peppered with justice!

Banner pic: https://www.gospelimages.com/paintings/96/the-return-of-the-prodigal-son?

Surrender and Win

We have heard it said so many times that life is a mystery; but isn’t that so because the One who has created us is a Super-Mystery? We have neither seen Him, so as to be able to judge for ourselves, nor have we heard enough about Him to say we know Him completely. Yet we go on from day to day, based entirely on our relationship with Him who is the Unknown but also the only One who can save us.

We humans are eyeballs that can’t see and earlobes that can’t hear, especially when we are immersed in the world. Yet, the Almighty addresses those who have eyes to see and ears to hear, particularly when we renounce worldly attractions, our mind and all our senses give us an understanding of the present and the final reality. When we give ourselves up in sweet surrender, God lets us in on the secret of His wisdom (Wis 9: 13-19), through the working of the Holy Spirit who has meanwhile descended upon us. Then we begin to appreciate God's ways and desires, for He reveals Himself to those desirous of that unique experience.

Seeing that humans had foolishly turned in on themselves and were acting like little gods, our Father in Heaven sent His Only Son Jesus to the world. In the Gospel today (Lk 14: 25-33) Jesus shakes the people out of their complacency. Putting all His cards on the table, He demands nothing less than total commitment, total acceptance of God’s ways and total surrender to the Father. As He says elsewhere, ‘Whoever is not with Me is against Me’.

Seeing that humans had foolishly turned in on themselves and were acting like little gods, our Father in Heaven sent His Only Son Jesus to the world. In the Gospel today (Lk 14: 25-33) Jesus shakes the people out of their complacency. Putting all His cards on the table, He demands nothing less than total commitment, total acceptance of God’s ways and total surrender to the Father. As He says elsewhere, ‘Whoever is not with Me is against Me’.

It is paradoxical but true that the more we give of ourselves to God, the more we feel free – it is a freedom easily verifiable from our everyday experience. Who can deny that the more we are attached to the ways of the world, the more we are in chains? Unbridled love for earthly things, be it money, power, influence, knowledge, is enslaving! On the other hand, how liberating it is to know and love God more and more!

That is why St Paul (Phil 9-10, 12-17) pointed out to Philemon, a man of high social standing, whom he had converted to Christianity, that it is of the essence that his slave, also a neo-convert, be treated humanely, as a brother in the faith. This new spirit in which the Apostle of the Gentiles wrote his short but important letter indeed prepared the world, mentally and spiritually, for a great transformation that finally led to the abolition of slavery.

The Lord has been our refuge from generation to generation! The readings of today invite us to keep a tab on the life of our minds and hearts, and to find out what can fetch us true peace and happiness. One thing is sure: without God’s help, we can do nothing – we are nothing! A sweet surrender to His will is a promise of our final victory.

Switching off our vanity lights

Today’s readings form an exceedingly beautiful trilogy. The folly of vanity is illustrated with a parable and rounded off with a nugget of wisdom about gazing heavenward. They make an interesting counterpoint to the capricious lifestyle of contemporary man.

Did you know that there was a time when ‘vanity’ simply meant ‘emptiness’ or ‘uselessness’ (from the Latin vanitas)? When used to represent arrogant or boastful obsession with one’s appearance, possessions or accomplishments, it underlined the same meaning. The original Hebrew term, sometimes translated as ‘illusion of illusions’, literally meant breath, wind, vapour, implying that things are uncertain, empty, futile.

The First Reading (Eccl. 1: 2; 2: 21-23) could not put it better. Life is indeed a string of vanities! Omnia vanitas: all is vanity. In fact, everything that is extravagant – and not useful or indispensable – is usually conceited: it focusses on the earthly creator and forgets the Divine Creator. This aspect of fallen man is something that Ecclesiastes, one of the ‘Wisdom Books’ of the Old Testament, has bared to thinkers and commoners alike. When its anonymous author says that there is ‘a time to be born and a time to die’, he tells us in no uncertain terms that life is brief and death inevitable.

That we are not masters of our destiny; that what we do lasts brief hours and weeks; that death comes like a thief: such thoughts flood our mind as we hear the Parable of the Rich Fool. Why, then, do siblings fight over land or even honest people build mansions to keep up with the Joneses? Is it not true that we must seek first the kingdom of God and the rest will be given unto us? How about burying our egos, surrendering to God’s will and giving up our acquisitive instinct for things that genuinely matter?

In today’s Gospel (Lk 12: 13-21), Jesus asks: ‘The things you have prepared, whose will they be?’ That’s a very pertinent question, for alas, how we take solace, nay, pride, in the abundance of our possessions, as though we are going to live for ever! But then, Covid-19 has taught us someting as perhaps only Covid can: that our life can change in an instant and from one day to another we may be catapulted to the presence of God. That’s when we will learn, albeit late, the full import of these words from Deuteronomy, with which Jesus shot down the devil in the desert: ‘Man does not live by bread alone but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.’

In effect, we are faced with an existential question: are we to sell everything, pack up our bags and head to the nearby forest? Clearly, not everybody is called for so radical a decision. We have to live in the world without being of the world; for it is not where we live, but how we live, that matters. Hence, St Paul, in the Second Reading (Col. 3: 1-5, 9-11), exhorts us to seek the things that are above, where Christ is; to set our eyes not on things that are on earth. He sets before our eyes a catalogue of vices that our old self has to be stripped of, and five virtues that our new self has to be clothed with, through baptism: a radical transformation by the action of the Holy Spirit.

In effect, we are faced with an existential question: are we to sell everything, pack up our bags and head to the nearby forest? Clearly, not everybody is called for so radical a decision. We have to live in the world without being of the world; for it is not where we live, but how we live, that matters. Hence, St Paul, in the Second Reading (Col. 3: 1-5, 9-11), exhorts us to seek the things that are above, where Christ is; to set our eyes not on things that are on earth. He sets before our eyes a catalogue of vices that our old self has to be stripped of, and five virtues that our new self has to be clothed with, through baptism: a radical transformation by the action of the Holy Spirit.

But is it all that straightforward? In the world today, it is difficult to be a Christian – not because Christ’s teachings have lost their relevance but because we seem to have lost our conviction. It is true that the secular powers-that-be are continually conspiring to splinter Our Lord’s precepts; on the other hand, haven’t the spiritual powers-that-be played to the gallery and capitulated to the ways of the world? And what are you and I doing to clear the stables? To be ruled by evil men is the price we pay for indifference to civil and ecclesiastical affairs!

The question remains: how do we proceed from here? Flashing before my eyes is St Pope Pius X’s motto: Instaurare omnia in Christ, to restore all things in Christ. To be committed Catholics, living the Gospel values to the best of our abilities, a life in communion with the Resurrected Lord should be our goal. The said Pope was acclaimed for his efforts to root out the Modernist heresy, which he dubbed ‘the synthesis of all heresies’, in his Encyclical titled Pascendi Dominici Gregis (8.9.1907). Much as we are programmed to love the word ‘modern’, Modernism represented an agnostic doctrine that attempted to pull the rug from under the Catholic faith. And, alas, it still does!

The trilogy of readings today invites us to go beyond self and see the world as it is. Isn’t vanity the leitmotif of the contemporary world? A culture of death is being promoted disguised as the culture of life. Engrossed as we are in our own personal worlds, more often than not we miss the larger picture. In fact, you and I unknowingly aid the advance of those cultural forces by the choices that we make every single day. It is high time we shunned the clutter outside and saved ourselves of that painful emptiness inside. Let not the city lights overwhelm us; let us switch our vanity lights and set our gaze on the True Light of the World.

Finally, on the Feast of St Ignatius of Loyola, let us pray that the words he famously said to St Francis Xavier soften our hearts too: 'What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his soul?' (Mt 16: 26; Mk 8: 36)

Prayer must be a way of life

To every believer whose desire is to know how to pray, here are some heart-warming pointers: in today’s Gospel (Lk 11: 1-13) we have a formula par excellence, and in the First Reading (Gen 18: 20-32), an illustration of how to pray. It is not ours to reason why, for if we are to survive, praying must come as easy as breathing. As Alexis Carrel, Nobel Laureate for Medicine, puts it: ‘Simple souls feel God as naturally as they feel the heat of the sun or the fragrance of a flower; but the same God, accessible to those who know how to love Him, remains hidden from those who do not understand Him.’

Abraham had no difficulty in relating to God who visited him in human form. They talked about Sodom and Gomorrah that were slated for severe punishment for their grossly offensive conduct. That is when Abraham began to do a deal with God, like a child would with his parents: he was concerned about the safety of his nephew Lot who had relocated to Sodom in a huff. Abraham left no stone unturned to secure a good ‘bargain’ as only he can do who knows God intimately.

Thankfully, Christian mystics from St Paul down to St Padre Pio have elaborated on kinds, methods and levels of prayer, and offered formulas; but none of them are crucial, for a child talking to his parent follows no fixed action pattern. The best policy is to be our honest selves, ready to do our Father’s will in all things, as the ‘Pater Noster’ counsels. While St Augustine reportedly said that he who sings, prays twice; St Aloysius of Gonzaga believed that work is prayer. Which goes to show that it is of the essence to establish a hotline with God and not merely employ a certain formula or method.

That God finally took a softer line at Abraham’s instance should be an eyeopener to those who doubt the efficacy of prayer! Such doubts stem from a secular attitude or a spirit that excludes God from our life. It is clear from today’s parable that God wants us to ask and persevere in the asking – while all the time believing with The Imitation of Christ, that ‘Man proposes; God disposes.’ And how can we forget the words of Our Lord Himself: ‘Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and it will be opened to you’!

Of course, that promise comes with a rider: we must have a change of heart; deep faith and trust in God; and pray calmly, humbly and confidently. We must praise and thank God, petition Him and intercede for others. When we leave it to Him to fix our broken lives soon we will hear our lips sing, ‘Lord, on the day I called for help, you answered me… Your kindness, O Lord, endures forever; forsake not the work of your hands.’ We have the Lord’s promise: ‘If you then, who are wicked, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask Him?’

Of course, that promise comes with a rider: we must have a change of heart; deep faith and trust in God; and pray calmly, humbly and confidently. We must praise and thank God, petition Him and intercede for others. When we leave it to Him to fix our broken lives soon we will hear our lips sing, ‘Lord, on the day I called for help, you answered me… Your kindness, O Lord, endures forever; forsake not the work of your hands.’ We have the Lord’s promise: ‘If you then, who are wicked, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask Him?’

But is that all as simple as it sounds? It is so if we do not let sin snap our hotline with God. At any rate, the Sacraments that can help restore it. We also need to create the right physical and psychological conditions to communicate with the Creator: for instance, personal prayer in the privacy of our rooms, and communal prayer in the sacral ambience of our churches. Notice how the interior of a monastery or the protected area of Old Goa or even a quiet and sprawling campus like Don Bosco’s situated in the middle of Panjim city can set the tone for a divine encounter: they are oases of tranquillity fit for the angels of India!

Although forces of evil are pressing against us, we must not be disheartened. St Paul in the Second Reading (Col 2: 12-14) puts things in perspective when he says that God has given us the ultimate gift of love through His Son Jesus Christ, thus securing us a return to the One we are united to through Baptism. So, even if our outer shell be diseased, the core of our being finds healing through prayer. We remain insulated against the fear of suffering, sickness and death if our life be a prayer offered to God, ‘an elevation of our soul to God’ (Tanqueray, The Mystical Life, cit. The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality, p. 765), a way of life!

Active and Contemplative

Do you wake up listless and dejected, upset about things not going your way? Do you dismiss a brand-new day as just another ordinary day? Well, if we give time to time, we might suddenly see things changing unexpectedly. What’s more, we will find that all things are possible – especially the impossible – when we are sustained by God’s Word! That’s putting things in perspective.

In the First Reading (Gen 18: 1-10), we are privy to a miracle. If Abraham, kind and obliging even at a ripe old age, seems to be without a worry in the world, it may help to know that he and his wife Sarah were heartbroken but had lovingly come to accept their situation. Abraham obliges his guests, not because he sees something in it for him but because he is an honourable man. The threesome leave before long – but not without announcing the good news that Sarah will bear a child. No doubt she laughs it off (note that Mary in her own case wondered, ‘how can this be’!) – but so it is: she gives birth to Isaac, a name that means just that: ‘he who laughs’ or ‘he who rejoices’! In short, nothing is impossible with God!

The Gospel (Lk 10: 38-42) has a matching situation. Here, Jesus is hosted by Martha and Mary. The elder sister’s busy chores are her presents for Jesus; the younger one, awestruck by every word that Jesus utters, honours Him with her presence. Truly, if simple living and high thinking is what a self-respecting guest values, it is more so Jesus, who is always about His Father’s business. Mary makes these words her own: ‘Speak, Lord, your servant hears; you have the words of eternal life.’ And Jesus praises her, for she has ‘chosen the good portion, which shall not be taken away from her.’

My dear departed grandmother used to say that faith and education none can take away from us. After all, that is what matters, for man does not live by bread alone but by every word that comes out of the mouth of God. So, when it is the Living Word alone that can sustain us, why settle for less? But alas, how often do we think of God in our everyday chores? How zealously do we mention Him at our glitzy social gatherings? How well do we recognise the voice of God in our daily encounters? Note that if Abraham were to despise the three men – seen as God Himself with two angels or, alternatively, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit – the ‘Father of Many Nations’ would have been father of none. Like Abraham, let’s get our priorities straight!

My dear departed grandmother used to say that faith and education none can take away from us. After all, that is what matters, for man does not live by bread alone but by every word that comes out of the mouth of God. So, when it is the Living Word alone that can sustain us, why settle for less? But alas, how often do we think of God in our everyday chores? How zealously do we mention Him at our glitzy social gatherings? How well do we recognise the voice of God in our daily encounters? Note that if Abraham were to despise the three men – seen as God Himself with two angels or, alternatively, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit – the ‘Father of Many Nations’ would have been father of none. Like Abraham, let’s get our priorities straight!

Can we rightfully say with St Paul in the Second Reading (1 Col: 24-28): ‘I rejoice in my sufferings for your [the Colossians] sake, and in my flesh [through his body] I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the Church’? As Christians, we are duty-bound to shun sadness and joyfully put our belief, hope and trust in the Lord – and then go on to love God and our neighbour as ourselves. We must stand firm for ever, as the Psalm says; if not, how will we admitted to the holy mountain?

To conclude, if all work and no play make Jack a dull boy, imagine how dull – and empty – we should feel if we always work and never pray! Let us make it a point to set aside quality time for God, listen to His voice and do His holy will. Let us delight in the presence of God and bless His Holy Name. Let’s not get too caught up with worldly things; rather, like Mary, let’s choose the good portion, and everything will fall in place. Let us balance action with contemplation.

Just as Jesus was not going to be with His friends for too long, we too will not live too long on this earth, will we? Let us, then, receive God in our hearths and homes today, so He recognises us tomorrow, when we knock on Heaven’s door!

Goencheo Mhonn'neo - I | Adágios Goeses - I

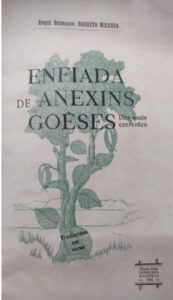

É possível que a literatura oriental seja ‘o mais precioso repositório de adágios e provérbios, como o é de fábulas e de contos populares,’ afirma João de Figueiredo[i] no prefácio à Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda.

Filho do grande literato Jacinto Caetano Barreto Miranda, de Margão, além de trabalhar como chefe da impressão da Imprensa Nacional, em Nova Goa (Pangim), colaborou na imprensa local com prosa e verso. De entre a sua obra poética, encontram-se Coisas sabidas (1923), Disparates em verso (s. d.), e ainda um e outro trabalho inédito.[ii]

Na Enfiada, vêm à luz 200 ditos regionais, que nas palavras de Barreto Miranda são ‘flores do folclore de Goa’. Recolheu-os, em primeira mão, na conversação da gente, traduzindo a maioria deles em duas versões, literal e livre, ambas transcritas mais adiante. Não se trata, pois, de provérbios, máximas ou sentenças, o que seria de sabor clássico, mas, simplesmente, de adágios, ditados, ou rifões, de sabor popular.

Dir-se-ia que esse trabalho prima pelo seu valor sociológico e poético. Uns anos antes, monsenhor Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado publicara, pioneiramente, em Coimbra, Florilégio de provérbios concanis (1922), contendo 2177 provérbios. Mas havia, sem dúvida, espaço para mais gente na seara.[iii] Barreto Miranda publicou anexins, dos mais correntes, no Heraldo, diário panginense, porém, numa altura em que poucos teriam dado conta do serviço que estava a prestar à terra.

Ainda por cima, traduziu os adágios, primorosamente, em verso, pondo-os assim em pé de igualdade com a sabedoria comum dos povos e a literatura universal.

Ainda por cima, traduziu os adágios, primorosamente, em verso, pondo-os assim em pé de igualdade com a sabedoria comum dos povos e a literatura universal.

Ora, quanto à ortografia e pronunciação dos vocábulos concanis, transcrevemos a seguir, como informação de utilidade, e não menos de curiosidade, as palavras de Barreto Miranda:

‘A escrita do concani – cuja ortografia em caracteres romanos, por não estar ainda bem definida – foi feita, para facilitar o leitor, possivelmente, conforme a fonologia popular em voga.

‘Relativamente à pronunciação: por não haver no alfabeto romano fonemas com que se possam exprimir precisamente certas palavras concanis, servimos da geminação de letras – letras cacuminais – as quais têm de ser fortemente articuladas com a ponta da língua, para dar o som aproximadamente natural da pronúncia concani. E para fácil enunciação, devem as palavras pronunciar-se em sílabas separadas. Para exemplo: melyá – kaddlyar – dounddolyá – vaurtolyak – devem ler-se assim: me-l-y-á – kadd-ly-ar – do-un-ddo-ly-á – va-ur-to-ly-ak.’[iv]

Não subscrevo de todo o sistema ortográfico seguido pelo estimado autor da Enfiada, limitando-me a observar que, quase um século após essa sua advertência, e apesar de, no enretanto, ter havido várias tentativas no sentido de uniformizar a ortografia e pronunciação da língua concani (sendo uma delas segundo o sistema Jonesiano, apresentada por monsenhor Dalgado), a situação continua no mesmo pé. Mas isso pouco retira o valor à Enfiada de Barreto Miranda.

Tradução literal | Tradução livre |

|

Melyá bagór sorg melâ na. |

Não se chega a ver o céu sem morrer. Não se alcança qualquer bem ou ventura sem passar por trabalhos e amargura. |

Tondd aslyar vatt assá. |

Quem boca tiver, tem via que quer. Chega para onde quiser, no país desconhecido, quem sua língua souber. |

Boreak guelyar fattir yetá. |

Por ir alguém fazer o bem, mais das vezes o mal lhe advém. |

Tenkdênn momv kaddlyar, tonddant poddâ na. |

Nunca a boca saboreia quando se quer apanhar, com cambo, o mel da colmeia. É melhor por si fazer, p’ra, o que se deseja, obter. |

Dounddo’lyá fatrár pãyon dovorçó nay. |

Não deixar nunca o pé assente sobre uma pedra movediça, (por se deslocar facilmente). É sempre acto de imprudência meter-se em negócio incerto ou coisas de contingência. |

Dongrá-vôylim zaddâm Dev ximptá. |

As plantas dos oiteiros (desprezadas p’la humanidade) são por Deus regadas. Aos que não têm lar, nem pão, sempre a Providência toma sob a sua protecção. |

Dholé add, sounsar padd. |

Fora da vista (e cuidado) o mundo fica arruinado. Quando o dono está ausente, as coisas, que lhe pertencem, são roubadas livremente. |

Muclyém zot vetá taxem, fattlém zot vetá. |

A junta de bois de traseira segue conforme anda a primeira. Do que o de diante faz, segue o exemplo o de traz. |

Dek’lem moddém, ailém roddném. |

O ensejo de encarar o cadáver, fez chorar. As ocasiões provocam acções. |

Borém corchém ani fattir gueuchém. |

Fazer o bem e afinal receber p’lo dorso o mal. |

[i] Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes, traduzidos em verso, de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), p. VI.

[ii] Cf. “A Evolução do Jornalismo na Índia Portuguesa”, de António Maria da Cunha (in Índia Portuguesa, volume 2, Nova Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1923); A Literatura Indo-Portuguesa, de Vimala Devi e Manuel de Seabra (Lisboa: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1971); Dicionário de Literatura Goesa, volume 1, de Aleixo Manuel da Costa (Macau: Instituto Cultural de Macau e Fundação Oriente, s.d.); Dicionário de Goanidade, de Domingos José Soares Rebelo (Alcobaça, 2012). Embora o Dicionário de Literatura Goesa se refira a um inédito intitulado “Frutos sem sabor”, disse-me Jacinto Barreto Miranda, sobrinho do Poeta, que não consta nenhum manuscrito desse nome no espólio do tio.

[iii] Thomas Stephens (c.1549-1619), missionário jesuíta inglês residente em Goa, publicara alguns adágios goeses na sua Arte da Lingoa Canarim, os quais foram traduzidos livremente pelo orientalista J. H. da Cunha Rivara (1809-1879), na segunda edição dessa gramática por ele publicada, em 1857. Isso para não falar de conjuntos posteriores, traduzidos em português e em inglês, estes por V. P. Chavan (Konkani Proverbs, 1900); S. S. Talmaki (Konkani Proverbs and Idioms, 1932), António Pereira, jesuíta goês, (Konknni Oparichem Bhanddar, 1985), e, mais recentemente, por Edward de Lima (Konknni Oparincho Kox: A Book of Konkani Proverbs, 2017); ou ainda os publicados em outros lugares de expressão concani, tal como nos estados indianos de Karnataka e Kerala.

[iv] Enfiada, pp. X-XI.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 17, Julho-Agosto 2022)

Being a Good Samaritan

Who can deny that the world would be a better place if we followed God’s commands to the hilt? No doubt, sincere people take to them like fish to water; they don’t find them difficult to follow, ignore them, play up or spurn them. The natural moral law is etched on our minds and we know it by heart. As the First Reading (Deut. 30: 10-14) says, ‘The Word is very near you: it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it.’ In the modern lingo, we are hardwired to love God’s law and must beware of worldly-wise, pirated software designed to infect the system!

God is not crazy or eccentric; His law is not ‘out there’, unusual and unconventional. He has had covenants with us, but alas, we have failed to honour them! In days of old, God spoke directly to His people or to a prophet. But then, being invisible had its flip side: God began to seem distant; so, He sent His Only Son to be born of a Virgin. Jesus walked the earth, spoke the language of the land, worked out miracles to everyone’s amazement, and died for our sins in an unprecedented outpouring of love. The essence of his parting message was that we love God and neighbour.

But isn’t that easier said than done? In the Gospel (Lk 10: 25-37), a Jewish scriptural scholar, after admitting that one can inherit eternal life only by loving God (Deut 6: 5) and neighbour as oneself (Lev 19: 18), demands to know who is our ‘neighbour’. His question makes sense for, to the Jews, only a member of their religion or race was a ‘neighbour’. The scholar probably wished to hear a novel definition that would navigate through issues like religion and ethnicity (Jews/Gentiles) gender and class (clean/unclean). Instead, Jesus responded with a parable that unimaginably expanded the scope of the term; and He topped it up with a question that dispelled all doubts!

In that touching and famous Parable of the Good Samaritan – reported by St Luke alone – he who attended to that half-dead man, with compassion, was from a region that the Jews looked down upon, thanks to their mixed ethnicity and their worship outside Jerusalem. Yet, Jesus introduces us to an individual Samaritan whose behaviour is a far cry from that of the Jewish priest and the Levite (temple assistant from the Hebrew tribe of Levi). Were these two too busy to stop and help, or were they merely playing it safe, for touching a dead man would prevent them from carrying out their temple duties! Or maybe not, for Jesus talks about them going from Jerusalem to Jericho, and not the other way around. While Jesus leaves the backstory a mystery, we can rest assured that God had moved the Samaritan to set an example to generations to come!

Which brings us to the Second Reading (Col 1: 15-20) in which St Paul emphasises that Jesus alone can inspire and help us humans to love and serve. The Apostle of the Gentiles portrays Christ as the mediator between Creation and Redemption: He who was present at the time of the creation of the world will also be the One through whom the world will be redeemed. Shouldn’t He, then, be the focus of our life? Our life makes sense only through Him. Note the repetition of the word ‘all’ in the passage: the writer wishes to emphasise the fact that there is nothing outside Him who is the Way, the Truth and the Life. He is the be-all and end-all of our existence. This reality can never be emphasised enough, lest we begin to sacrifice the truth of the Gospel to the distorted values of the contemporary world.

The values of the contemporary world are centred on money, influence and power. They keep us bonded; they prevent us from reaching out to others in love, as Jesus did. Subservience to the material world is a despicable form of bondage that only God’s laws have the power to liberate us from. Hence, Jesus alone is deserving of our trust and confidence; He is our only model for doing things through love. So, it is not good businessmen but Good Samaritans are God’s instruments of hope – fools for Christ, in this mad, mad world!

However, being a Good Samaritan does not mean being naïve; it does not demand suspension of our critical faculties. In the near-Godless world we live in, steeped in malice and misunderstanding, Good Samaritans must indeed act with discernment. Wherever we may find ourselves – be it at home or at work; in a school or a hospital, in the street or on the battlefield – reaching out to our neighbour is of the essence. One sure way of doing this is to ward off pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath, and sloth. When we evict those seven trespassers, God comes into our minds and hearts, moving us to be Good Samaritans in a way that is most pleasing to Him.

Mudança... unforgettable vacation in Goa! (2)

This is the second and final part of the testimonies translated from my podcast Renascença Goa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=24yo5MFthrg and published in Revista da Casa de Goa.

We first have GABRIEL DE FIGUEIREDO, who lives in Melbourne, Australia. He recalls the days that he spent his holidays at Colva beach and in his native village of Loutulim, both in the taluka of Salcete.

We first have GABRIEL DE FIGUEIREDO, who lives in Melbourne, Australia. He recalls the days that he spent his holidays at Colva beach and in his native village of Loutulim, both in the taluka of Salcete.

What I understand by mudança: for us kids, mudança was a change of environment - it was going from the city of Panjim, where we lived during school days, to the village of Loutulim and Colvá to spend the holidays and refresh the “soul”. Until about 1964, our Aunt Margarida used to arrange a little house in Colvá for us to spend the month of April, to enjoy the fresh sea air and take a bath, or swim in the sea waves. Our uncles Sebastião (from Margão) and Francisco (from Benaulim), together with their families, used to join us to spend their April holidays there. I don't know why after 1964 we stopped going to Colvá – maybe the owner of the house had changed.

What I understand by mudança: for us kids, mudança was a change of environment - it was going from the city of Panjim, where we lived during school days, to the village of Loutulim and Colvá to spend the holidays and refresh the “soul”. Until about 1964, our Aunt Margarida used to arrange a little house in Colvá for us to spend the month of April, to enjoy the fresh sea air and take a bath, or swim in the sea waves. Our uncles Sebastião (from Margão) and Francisco (from Benaulim), together with their families, used to join us to spend their April holidays there. I don't know why after 1964 we stopped going to Colvá – maybe the owner of the house had changed.

Well, as ours was a musical family, after returning from the beach to the little house, it was time for solfeggio, singing and violin. Apparently, it was here that my father, António, started writing Mandó arrangements after his return to Goa on completion of his training in orchestra conducting at the University of Paris.

Well, as ours was a musical family, after returning from the beach to the little house, it was time for solfeggio, singing and violin. Apparently, it was here that my father, António, started writing Mandó arrangements after his return to Goa on completion of his training in orchestra conducting at the University of Paris.

When we returned to Loutulim to spend the month of May, we had access to home-grown mangoes, jackfruit, cashews, etc. Even in Colvá and also in Loutulim, as there was no electricity supply at the time, Aladdin or Petromax lamps were used at night to give enough light to read. And I read a lot of books those days, more in English than Portuguese, because my maternal grandfather had a book-case full of Reader's Digest, National Geographic, novels like The Saint (Leslie Charteris), Sherlock Holmes, etc. Around 25 May, a feast of Enthronement of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Mary used to be celebrated, along with uncles and cousins who also came to spend a few days with us.

Those were days full of happiness and games. The mudança in October was only to Loutulim, taking advantage of the mid-term vacation that coincided with the Divali festival. We used to hold a novena to Our Lady of Sorrows in the second half of October, with a Rosary sung in Latin and Konkani, on alternate days, the ‘Salve Rainha’ followed by ‘Virgem Mãe de Deus’, both sung in Portuguese.

In those days, it was customary for all uncles and cousins to come to spend holidays with us in Loutulim, until the last day of celebration. It was ten days of absolute happiness. Well, after my father passed away in November 1981, this tradition of the month of October came to disappear, unfortunately. My brother Vicente makes an effort to maintain the tradition of Enthronement, along with my sisters Teresa and Celina, inviting cousins and their families (now extending to a few generations) to sing a litany in May, when they go to Loutulim for a mudança when possible.

In those days, it was customary for all uncles and cousins to come to spend holidays with us in Loutulim, until the last day of celebration. It was ten days of absolute happiness. Well, after my father passed away in November 1981, this tradition of the month of October came to disappear, unfortunately. My brother Vicente makes an effort to maintain the tradition of Enthronement, along with my sisters Teresa and Celina, inviting cousins and their families (now extending to a few generations) to sing a litany in May, when they go to Loutulim for a mudança when possible.

Our next guest is SAADIA FURTADO, from Chinchinim. She remembers spending holidays in Fatrade beach in Varca village.

Our next guest is SAADIA FURTADO, from Chinchinim. She remembers spending holidays in Fatrade beach in Varca village.

In Goa, the word Mudança is used in a slightly different manner from its original meaning: it means mental rest accompanied by physical relocation. In general, one would go for a mudança during a weekend or when there were public holidays. People from inland areas went to the beach to enjoy the fresh air and to bathe in the sea. It was a healthy practice. One could also go for a mudança by going to a relative's or friend's house or live in a rented house in places where there are fountains and springs which have sources of medicinal properties in water, especially in the case of patients with high blood pressure!

In Goa, the word Mudança is used in a slightly different manner from its original meaning: it means mental rest accompanied by physical relocation. In general, one would go for a mudança during a weekend or when there were public holidays. People from inland areas went to the beach to enjoy the fresh air and to bathe in the sea. It was a healthy practice. One could also go for a mudança by going to a relative's or friend's house or live in a rented house in places where there are fountains and springs which have sources of medicinal properties in water, especially in the case of patients with high blood pressure!

I fondly remember our mudança to Fatrade Beach at Varca, during the months of April and May. There I spent a few days in the company of my parents and relatives. It was a mudança that helped us rejuvenate.

I fondly remember our mudança to Fatrade Beach at Varca, during the months of April and May. There I spent a few days in the company of my parents and relatives. It was a mudança that helped us rejuvenate.

Nowadays, we talk about, that is, when someone goes from one state or country to another for about a week or a fortnight. This meaning is considered different from the term mudança in Goa.

Finally, FAUSTO COLLAÇO, who lives in Margão, goes down memory lane to the holidays spent at his ancestral villages of Raia and Benaulim.

The covid-19 pandemic and its mutant waves heckle us. When talking about holidays, the only holidays we could think of at the moment is to stay at home and spend the holidays there. However, this compulsory retreat takes us back nostalgically to the holidays we used to spend during our childhood, in Goa – the Goa that was for us and the tourist, a Paradise!

When children, we enjoyed semestral holidays. They lasted for over a month each time and so, offered the right opportunity for some holidays during which we stayed over at our grandparents' place in the village! On my mother's side it was the beautiful village of Benaulim and on my father's side it was Raia.

Coming to Benaulim was for us, setting foot on a Fairyland of boundless freedom and fun! My grandparents' place was a confluence of all people - cousins, uncles and aunts, granduncles and aunts, domestic help and, beyond the walls of the house, family friends and the entire village of Benaulim – from the smallest to the greatest! The chapel in the neighbourhood, tolled its bells morning and evening, proclaiming as though, the dawn and dusk! The children whiled away their time at play and also planning out small skits and recitals which accompanied the dinner of the older people at home. They in turn, were an ocean of love and affection! My grandmother used to bring to the table savoury traditional dishes, pickles and desserts. There was always abundant seasonal fruit like mango and jackfruit.

The evenings were often spent in walks by the beach where one would always meet up with friends. We went on occasional picnics in family or in groups. The picnics were naturally regaled with singing and guitars strummed by my uncle Joaquim or other friends. At sunset, the little feet happily plodded back home where, in those bygone days, one was welcomed to the shimmer of kerosene lamps!

The evenings were often spent in walks by the beach where one would always meet up with friends. We went on occasional picnics in family or in groups. The picnics were naturally regaled with singing and guitars strummed by my uncle Joaquim or other friends. At sunset, the little feet happily plodded back home where, in those bygone days, one was welcomed to the shimmer of kerosene lamps!

The ensuing holidays were spent in Raia – my father's ancestral village. It was a particularly quiet and peaceful village. Our house stood in the remote interior, in a ward called 'Santemoll'. It was calm and far from the bustle of the city. Once there, one only heard sounds of nature: birds chirping, distant joyful shrieks of children playing, the bellow and the moo. A river flowed luxuriously a little distance away. Other familiar sounds were the honking of the door-to-door bread or fish vendors and the tinkling of the postman on his cycle. He always had a smile, was cheerful and courteously greeted us while even waggling a tad of Portuguese!

Here too, we enjoyed seasonal fruit and, towards the end of May, heralded by lightning and intimidating thunder, came the showers – initially a light drizzle which soon swelled into a heavy downpour! The gutters gurgled noisily and the fields flooded up with rainwater. The weather cooled, grasses and weeds sprouted here and there. There was a burst of green everywhere! The ploughman plunged into work toiling the fields with a pair of oxen and a wooden plough, swinging into action his strong and able arm, with a dextrousness defined by many years of experience! He transformed the field into a veil of greenery undulating in the breeze - an enchanting sight for the locals and tourists alike!

Such was the idyll of village life in Goa and of our holidays in the villages! Today, consequent to changing times, they're quite different and are on their way to even greater transformation. One hopes, however, that this idyll which was the life and the land of Goa, will never be lost altogether.

------

Acknowledgement: Many thanks to the three guests for their respective translations published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 17, July-August 2022. The third text was further edited by the respective author for this blogpost.

On the mission field

Today’s readings grab our attention: the first, by Isaiah’s colourful imagery (Is 66: 10-14); the second, by St Paul’s passionate testimony (Gal 6: 14-18); and, of course, the third by Jesus’s stirring voice (Lk 10: 1-12, 17-20). Close on the heels of last Sunday’s Gospel passage, which invited us to be resolute in disseminating God’s Word, Our Lord brings into sharp focus the mission of His disciples – which is our mission too!

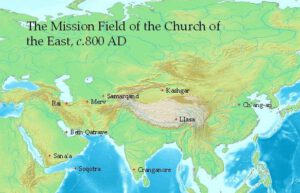

Coincidentally, in India, 3 July is the Solemnity of St Thomas, the Apostle. The readings proper to the occasion are from Acts 10: 24-35; Heb 1: 2-3 or Pet 1: 3-9; and Jn 20: 24-29, whose last sentence from the mouth of Jesus is ‘Blessed are those who have not seen, and yet believe’. However, we are going to comment on the readings proper to the universal Church; by God’s grace, they also fit like a glove, dwelling as they do on the life of a missionary, which St Thomas was one par excellence.

A fragment of today’s Gospel reading rings in the ear of every believer: ‘The harvest is plentiful, but the labourers few.’ How many did Jesus commission? Some codices say seventy, others seventy-two: both figures are right, as they represent the pagan communities (70 in the Hebrew text, 72 in the Greek) mentioned in Genesis 10.

St Luke is the only Evangelist who makes a mention of this number, suggesting that Jesus would not limit Himself to the twelve tribes of Israel (denoted by the Apostles) but would reach out to all communities and nations. One of them, St Thomas, travelled to South India and died there. And as members of the Church today, it is our responsibility, until the end of the world, to evangelise like them, without fear or favour.

It is noteworthy that Jesus spoke to the seventy-two after He had spoken to the Twelve (see Lk 9). Thus, the Gospel was proclaimed first in Israel and thence to others. Jesus commanded the disciples to go ahead of Him into every town and place. That He sent them out ‘as lambs in the midst of wolves’ spoke volumes of the trials and tribulations awaiting them in a hostile world. Yet, He bid them to carry no purse, no bag, no sandals, and to salute none along the way: He expected them to trust in Him alone.

The disciples also received some practical tips from the Divine Master. They were not to waste time in elaborate greetings, so typical of Oriental cultures, but to focus on announcing the Good News without delay. The disciples were to eat, drink and accept accommodation as provided to them, for the labourer deserves his wages; but they were not to have expectations or make demands – for God would sustain them. They had to reach out to the sick – not only physically but spiritually – by giving them the hope of eternal salvation.

Jesus made an interesting distinction between what was to be the disciples’ behaviour in a household and in a town per se. Not only would their greetings differ, but their attitude as well. If an individual or his household refused the disciples, the latter’s response would be milder than when a town rejected them. In the latter case, Jesus recommended that they shake off the dust of their feet. He promised them authority over the enemy and that their names would be written in Heaven. The disciples fulfilled their mandate diligently and, no wonder, they returned with joy.

If Our Lord’s occasionally tough language does not match that goody-goody image of Him, let’s remember Jesus was not a goody-goody; He called a spade a spade, was earnest about his Father’s holy business and brooked no nonsense. Thus, the peace His disciples carried went beyond mere greetings of good health and prosperity; it was a messianic peace. And the hard-hitting words that Jesus and His disciples uttered were but messianic lamentations, for the fate that awaits detractors is one worse than Sodom’s.

If Our Lord’s occasionally tough language does not match that goody-goody image of Him, let’s remember Jesus was not a goody-goody; He called a spade a spade, was earnest about his Father’s holy business and brooked no nonsense. Thus, the peace His disciples carried went beyond mere greetings of good health and prosperity; it was a messianic peace. And the hard-hitting words that Jesus and His disciples uttered were but messianic lamentations, for the fate that awaits detractors is one worse than Sodom’s.

Jesus expects us to adopt a like posture; we are not to trivialise God. St Paul, who witnessed similar crises in the communities he tended, concludes his letter to the Galatians, by stating that salvation lies only in the Cross of Christ: ‘I do not wish to take pride in anything except in the cross of Christ Jesus our Lord,’ he said unequivocally. This is an eye-opener for us who we must learn to guard against sacrificing the truth of the Gospel to materialistic values and goals. Let us not doubt, let us not harden our hearts when we hear the Lord’s words.

We who have had the fortune of meeting our awesomely loving God must proclaim His works. The prophet Isaiah fashioned most beautiful images to give us an idea of God’s unfathomable love: it is like that of a mother for her child; of a husband for his wife; of a bridegroom for his bride. We too must acknowledge God’s omnipresence, omniscience and omnipotence. We must strive to be true disciples of Christ, the salt of the earth and light of the world. We must not hide the light under a bushel but set it upon a lampstand so that it radiates light to all in the world.

If we announce what God has done for our souls with true missionary zeal, the world will cry out with joy and sing glory to His name!