Konkani before and after Dalgado

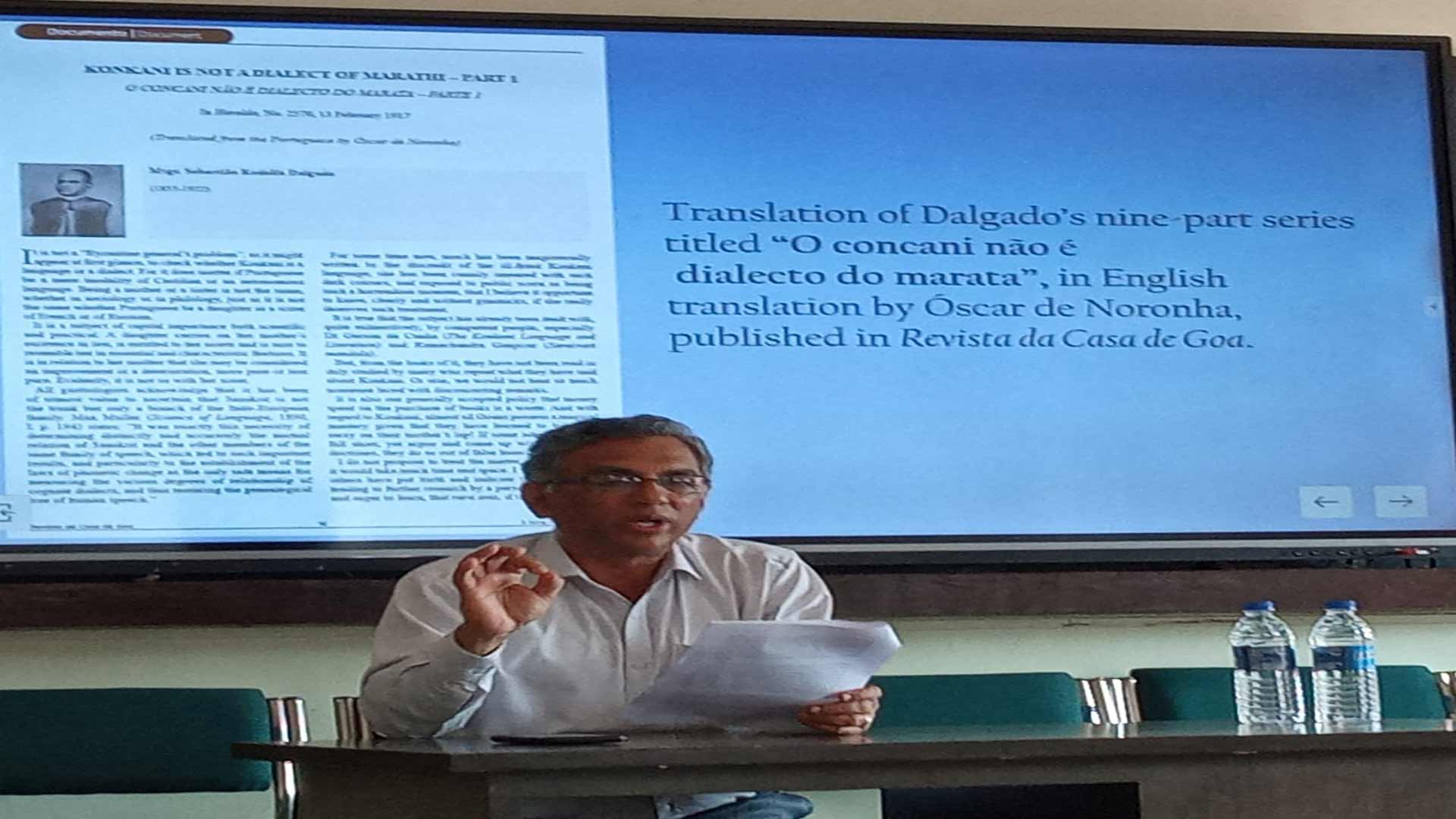

In 1917, Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, an internationally renowned Goan linguist, forever changed the course of the Konkani-Marathi controversy. In a nine-part series titled “O concani não é dialecto do marata” (‘Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi’), published in the Panjim daily Heraldo, he analysed the linguistic and grammatical characteristics of Konkani, demonstrating its identity as distinct from that of Marathi. But, then, what events led Mgr. Dalgado to write the series?

Fabricated controversy

The Konkani-Marathi controversy is not as ancient as it might seem; it is a nineteenth-century fabrication. Konkani, which, like Marathi, evolved from Prakrit, began to make rapid strides in the linguistic, lexicographic, and literary fields, thanks to the ingenuity of European missionaries in sixteenth-century Goa. It is another matter that their interest began to wane, and indifference turned into state hostility, to some extent, at least on paper. This brought the first modern literary period of Konkani literature to an inglorious end.

In the eighteenth century, literary production in Goa was conspicuous by its absence, due to the shutdown of the printing press. As a result, not only did Konkani get relegated to the background, but Goa itself became a backwater. Even so, there was not a doubt about Konkani’s linguistic status until the year 1807, when John Leyden dubbed it a dialect of Marathi. His ideas began to gain currency in British India. When those echoes reached Portuguese India, Konkani was excluded from the curriculum of the first state-owned schools set up in 1831. By now, in the new Liberal regime, it suited Goan Catholic elite to adopt Portuguese as their cultural language, while the Hindu elite continued to seek refuge in Marathi and turned to Portuguese in the following century.

Meanwhile, in 1858, J. H. da Cunha Rivara’s famous essay on the Konkani language (Ensaio histórico da língua concani) decried Goa’s contempt of its native language and defended its dignity. His realisation was perhaps a byproduct of a new Orientalist consciousness, which prized the rediscovery of indigenous languages. But alas, it is Marathi and not Konkani that drew the benefit. In 1869, at the behest of Goa’s official translator Suriagy Ananda Rao, the state government banned the use of Konkani, while Marathi ruled the roost at the Panjim Lyceum.

A decade later, when R. G. Bhandarkar in Bombay reiterated Konkani’s dialect status (cf. Wilson Philological Lectures, 1877, a series of seven lectures on the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages), scholars favouring the dialect theory slightly outnumbered those favouring the language theory. But a fitting reply awaited Bhandarkar in 1881, when José Gerson da Cunha systematised and coordinated the arguments of the language theory in his Konkani Language and Literature. Nonetheless, in 1905, the Linguistic Survey of India, published by the British Government, buttressed the dialect myth.

Divided Goa

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

While the Konkani movement was thus gaining momentum within the community in Bombay, back in Goa, Thomaz de Aquino Mourão Garcez Palha and Fernando Leal, two mestiços (persons of mixed blood, Portuguese and Goan), who had probably caught the Orientalist bug, began a crusade for the “resurrection of Konkani”. They were supported mostly by members of the Goan Catholic elite.

As regards the Hindu elite, in 1916, when the ayurvedic physician Dada Vaidya (Ramachondra Panduronga Vaidya) spoke in Konkani at Goa’s first Provincial Congress, Marathi writer Xamba Suriarao Sardesai shouted him down and followed it up with a two-part article disparaging the Konkani movement. The division of Goan society was complete, not only between educated Christians and Hindus, but also within the Hindu community.

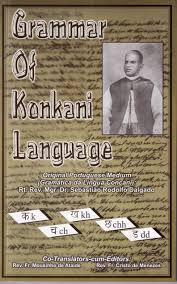

By February 1917, therefore, the stage was set for Dalgado’s intervention from distant Lisbon. The tireless Goan Catholic missionary was now on a mission to prove Konkani’s credentials as a language. He had published a Konkani-Portuguese dictionary in Bombay (1893), and a Portuguese-Konkani dictionary in Lisbon (1905), both of which used the Devanagari and Roman scripts. The university professor and Fellow of the Portuguese Academy of Sciences was an authority on the influence of Portuguese on Asian languages, and his thoughts kept returning to Konkani. Significantly, his last unpublished work was a Konkani Grammar, which Fr Mousinho de Ataíde translated into English in Dalgado’s death centenary year, 2022.

Decisive entry

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s entry was decisive. It was a watershed moment in the history of Konkani Studies. Portuguese-language newspapers in Goa as well as bilingual papers in Bombay began to comment on Dalgado’s efforts in the field. After him, Jules Bloch showed how distinct Marathi was from Konkani; S. M. Katre paralleled Bloch’s book by writing The Formation of Konkani, and together with V. P. Chavan, helped further Konkani’s position as a separate language.

Varde Valaulikar’s writings continued Dalgado’s work of demonstrating Konkani’s individuality. Curiously, Shenoi Goembab began by writing in Marathi, and after switching to Konkani, first wrote in the Roman script. Seven of his twenty-nine books are in the Roman script. In fact, there was no Konkani worth the name in the Devanagari script in Bombay, and much less in Goa.

Perhaps Dalgado and Valaulikar never met or exchanged correspondence, but they shared the same vision. Valaulikar, who knew Portuguese, must have read Dalgado’s rejoinder to Xamba Sardesai. While Valaulikar carried out a literary crusade in Bombay, Dalgado’s academic legacy was kept alive by his pupil Mariano Saldanha in Lisbon. Dalgado died in 1922, and Shenoi Goembab in 1946. In 1952, Mariano Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth All-India Konkani Porixod held there. As a votary of the Roman script, Saldanha’s address was printed in the Roman script.

By the 1950s, the demand for linguistic states had gained significant momentum, leading to the creation of the Telugu-speaking Andhra out of the State of Madras. Much earlier, the Indian National Congress had organised its provincial committees along linguistic zones, signalling an early form of the concept. Dalgado and Valaulikar’s vision of Konkani in the Devanagari script dovetailed into that concept, whereas Saldanha envisioned the Roman script for Konkani in Goa. It did not materialise in the post-1961 scenario, for obvious reasons.

Goa post-1961

It was an entirely new ballgame after Goa got into the Indian Union. Maharashtra had laid claim to Goa, deeming Konkani a dialect of Marathi. The Goan elite, which was once divided between Portuguese and Marathi, leaving Konkani to fend for herself, now realised that only Konkani could help preserve their identity. It was a David and Goliath situation, in which Konkani won because the language was on the people’s lips and nobody could take it away. Its literature was perhaps not on a par with best in the country, but it had a strong foundation built by Dalgado and Valaulikar.

Hence, while Valaulikar is regarded as the Father of Modern Konkani Literature, Father Dalgado, by his fundamental contribution to the development of the language, ought to be regarded as the Grand Father (pun intended) of Modern Konkani. Their impact was felt at the time of the Opinion Poll and when Sahitya Akademi recognised Konkani as a literary language; when Goa achieved statehood and Konkani became the state language, and when Konkani was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution.

Thereafter, Konkani came into a privileged position, as never before. It would seem like a time to consolidate had arrived. For instance, in the Konkani world beyond Goa, it would pay dividends to make the most of the multi-script situation; but that was not to be. In Goa, the issue of script remains Konkani’s Achilles heel. The sooner this is resolved the better, to ensure the interests of all the user communities; their wellbeing is bound to produce positive results for the popularity and expansion of the language. The more the scripts the better.

Case for the Roman script

It is also a time for some reflection. Has the shared legacy created by Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab been put to creative use? It would be interesting to consider what their response would be to our globalised world. How would they respond to demands for recognition of the Roman script in today’s multilingual and multicultural world? Would they consider it an opportunity to woo back Konkani speakers at home and in the diaspora, and to win new speakers from across the big wide world? Would they appreciate the possibility of Konkani finally becoming at once a means of communication and identity marker?

After all, living languages are dynamic, and no script is perfect. Goykanadi was the earliest known native script that Konkani used, before it was supplanted by others. Similarly, the earliest known script for the English language was the Anglo-Saxon futhorc. From the seventh century onwards, the Latin alphabet began to replace the futhorc, though they coexisted for a time in England.

It is the same in India. The Latin or Roman script is not to be considered foreign; it is as Indian as the English language in the country. If the English language can be made official, so can the Roman script, or any other for that matter, if numbers and the volume of work justify it.

Not to let script remain a divisive issue, would Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab, then, consider letting Goa be the first state in the Indian Union to successfully resolve a multi-script situation? Any script that has worked in the past ought to work in the future. This applies to the Roman script as well. Surely, Dalgado’s mission was to save the language over and above the script.

A Distinguished Goan Scholar

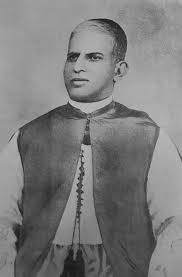

After one has met a grand old man born just two decades after the Sepoy’s Mutiny, history cannot but look like a thing of the present. He migrated to Lisbon in the year of the Great Depression. He spent his post-retirement years in Goa and died several months after Portugal formally recognised the Indian takeover of his native land. He was a near-centenarian, but that is the least of his claims. He made history in more ways than one.

Dr. Mariano Saldanha (1878-1975) of Ucassaim was a physician-turned-indologist who studied history, language, literature, and culture. He was the nephew of Fr Gabriel de Saldanha, the author of the classic História de Goa. In 1905, he graduated in medicine and pharmacy from Goa’s iconic medical school. After a few years of professional practice, he left for Portugal to study Sanskrit under Mgr. Dalgado at the University of Lisbon. It was not unusual then for a man of science to show an interest in the humanities, but his was a total switch.

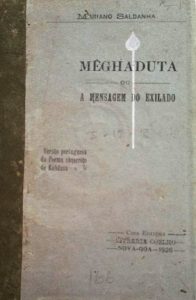

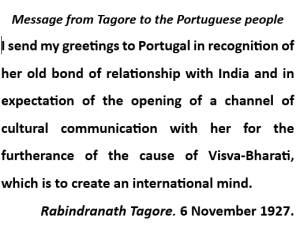

On his return in 1915, he taught Marathi and Sanskrit at the Panjim Lyceum and translated Kalidasa’s Meghaduta into Portuguese. In 1929, he was back in Lisbon, now a professor of Sanskrit at his alma mater. He proudly carried a message of friendship to the Portuguese people from Tagore, whom he visited in Shantiniketan. In 1946, he was appointed as the deputy director of Escola Superior Colonial’s Institute of African and Oriental Languages. He taught Konkani there until his superannuation in 1948.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

On the milestone anniversary of this distinguished scholar, we recall his precious contribution. Mariano Saldanha’s affinity to history and languages was evident from an early age. He pursued fundamental research in the Konkani language in Lisbon. He spent countless hours in libraries, archives, and museums, sifting through books and manuscripts with a scrupulous eye for the smallest clue.

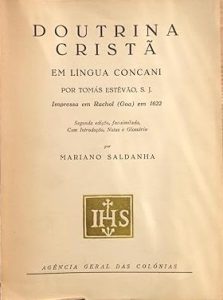

In 1945, Professor Saldanha produced an annotated facsimile edition of Thomas Stephens’ Doutrina cristã em língua concani (Christian doctrine in Konkani, 1622). In 1950, he unearthed sixteenth-century Konkani and Marathi manuscripts in Braga’s public library. The love of truth drove him forward not only to discover but also to share the fruits of his discovery. He did so even with his ideological dissenters, such as A. K. Priolkar.

In 1952, Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth Konkani Parishad. Being a strong votary of Konkani in the Roman script, his address was published accordingly. Curiously, this is his only text written in Konkani. When he sensed the political winds of change, he began to emphasise Goa’s distinctiveness in the Indian subcontinent, through its language, Konkani; the Lusitanian influences on its culture; the roots of Western music; its pioneering printing endeavours, and its Christian Puranic literature.

After his death, his family gifted his large book collection to the Xavier Centre of Historical Research. His microfilms and manuscripts show his discipline and patience. He was a member of several academic bodies and published his writings in journals and newspapers. They depict him as a thorough academic researcher, an exacting reviewer, and a formidable polemicist.

However, nothing prevented the good old bachelor from being patient with the youngsters. Maria Helena Saldanha de Santana Godinho told me of how she used to lap up information and pearls of wisdom from her granduncle. While, thanks to his prodigious memory, he recounted stories with ease, she happily fit those anecdotes about Akbar, Shivaji, and other Indian greats, in her school answers.

At age 6, this writer had an unforgettable first encounter with the then-nonagenarian professor. He had unveiled the bust of world-renowned oncologist Dr. Ernest Borges, his grandnephew, at Asilo Hospital, Mapuçá, and addressed the gathering. It was an emotional moment. After the ceremony, the Professor was asked if he would mind a slight delay in his ride home. His stern reply was, ‘Yes, I mind.’ But then, the delayed laughter said it all.

For their part, the citizenry today should mind that the memory of Goan notables is often taken for a ride. They deserve better from our civic, academic, and governmental bodies if we are to achieve a seamless transition from the past into the present.

Banner: Dr Mariano Saldanha delivering the presidential address at the Fifth Konkani Parishad, Bombay, 1952

This article was first published in Herald, Panjim, on Dr Mariano Saldanha's 50th anniversary of death, 23 Oct 2025

The Red Line

Is God someone who takes the fun out of our situation? Two of the three readings of today are indictments of our behaviour, and one prescribes a treatment.

The First Reading (Amos 6: 1.4-7), originally meant for the upper crust of the kingdoms of Judea and Israel,[1] is also a message for all people, whether in Goa or California. In a passage reminiscent of the Woes listed by St Luke, the prophet Amos decries those who only live to eat, drink, and make merry; who ‘lie upon beds of ivory and stretch themselves upon their couches’, and show least concern for their suffering brethren. They are beneficiaries of God’s largesse, yet ‘not grieved over the ruin of Joseph’ (a reference to the ten tribes of Israel with whom Joseph’s name became synonymous).

The Gospel (Lk 16: 19-31) puts it all in a parable that is unique to the Evangelist St Luke. An unnamed rich man who cared for none but himself is tormented in Hell, whereas poor Lazarus (not the one raised to life in John’s Gospel), who was at his mercy on earth, now enjoys the Beatific Vision. It is not an indictment of riches, but of our wretched attitudes. Deposuit potentes: God puts down the mighty from their seats,’[2] or, as Mephistopheles says in Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus: ‘Fools that will laugh on earth must weep in hell’.

In the midst of it all, the rich man requests God to forewarn his family that Hell is for real: ‘lest they also come into this place of torment’. This was perhaps his only charitable thought, whereas Lazarus (meaning ‘God is my help’ in Hebrew) had the Lord to turn to. Indeed, God is ‘just to those who are oppressed’, ‘who gives bread to the hungry’, ‘who sets prisoners free’, ‘who gives sight to the blind, who raises up those who are bowed down’, ‘who loves the just’, ‘who protects the hungry’, ‘He upholds the widow and orphan but thwarts the path of the wicked’ (cf. today’s Psalm 145: 6-10).

Can God who cares for us be against human enjoyment or amusement? All He asks of us is not to cross the red line between right and wrong. In this sense, every day of our life is a reenactment of the dilemma of the Garden of Eden. Hence, in the Second Reading (1 Tim 6: 11-16) St Paul exhorts us to ‘aim at righteousness, godliness, faith, love, steadfastness, gentleness’—six basic virtues. There is no need for highly wrought theology but for an open heart to understand all of that. Highlighting God’s kingship vis-à-vis the sinful practice of paying tribute to false gods, he urges us to ‘fight the good fight of the faith’ and praise the Lord ‘Who alone has immortality and dwells in unapproachable light.'

In time, we realise that God does not take the fun but the sin out of our situation! He has given us the Scriptures and the Commandments to guide us, and the Sacraments to strengthen and help us to stay within the lines. If we obey, we have everything to gain, if not, everything to lose in the life hereafter. But that’s not all. We have to reach out, show concern for others, and be proactive. Lukewarmness and indifference can be lethal.

Jesus who has said, ‘I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life’ (Jn 14: 6), and ‘I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full’ (Jn 10:10) promises us not temporary but eternal joy as only He can.

Banner: By MOSSOT - Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15941723

[1] After the death of king Solomon, the United Kingdom of Israel, whose capital was Jerusalem, was divided into the northern kingdom (Israel) with Samaria as its capital, and the southern kingdom (Judea) with Jerusalem as the capital.

[2] These words belong to the Blessed Virgin’s Magnificat (Lk 1: 46-55).

Desdobrando Goa | Unfolding Goa

Editorial

https://online.fliphtml5.com/bcbho/hzql/#p=1

A nossa minúscula Goa tem o condão de se desdobrar em diversas Goas. Existe a Goa da história e a da contemporaneidade, a Goa geográfica e a dos corações espalhados pelo mundo, a Goa real e a dos nossos sonhos. Há, portanto, diversas Goas. E dentro de cada uma existem engrenagens sociais, económicas, políticas e culturais, sempre a rodar. Quem imagina conhecer as múltiplas Goas vive a fábula indiana dos Cegos e o Elefante.

Todavia, a Revista da Casa de Goa empenha-se por interpretar essas Goas aos leitores. É o caso da presente edição, que começa por falar de Pangim, a poética capital goesa, que dantes teve outros nomes: Nova Goa e Cidade de Goa. O nosso editor associado José Filipe Monteiro conta a interessante história de como, no século XIX, esse modesto bairro da aldeia de Taleigão passou à capital do império português oriental.

Por mera coincidência, outro editor associado, Valentino Viegas, recorda na sua crónica os “doces anos” que viveu em Pangim e em calções percorreu os seus cantos e recantos. E, que maravilha, ficarem de repente, lado a lado, a grande e a pequena história da Índia Portuguesa.

Não é, porém, maravilha a situação que de momento se vive em Goa. Leia-se o artigo intitulado “Será Goa a próxima Ayodhya na Índia?”, de Ivo de Noronha. Goa, aliás, destacada pelo modelo de coexistência pacífica que representa entre as diversas comunidades e pelo seu forte senso de identidade cívica, enfrenta hoje um desafio tão subtil quão insidioso.

Em situações dessas, é tão reconfortante lembrar, como o faz David Pinto, no seu artigo “Globalização em Goa: a contradição asiática”, que essa mesma Goa foi na verdade uma das primeiras sociedades multiculturais e globais de todos os tempos. Acrescenta que, ainda no século XXI, viver em Goa “proporciona uma experiência diferente da de qualquer outra parte da Índia”.

Nota-se esse tipo de pioneirismo na recente nomeação papal do padre jesuíta Richard Anthony D’Souza como Director do Observatório do Vaticano. Prova de como um goês naturalmente se torna cidadão do mundo. Na secção de notícias, damos pormenores dessa honrosa atribuição.

É afinal a sua cultura multissecular que define Goa. Veja-se o caso de Manohar Rai SarDessai, cujo “papel cultural híbrido, ao navegar pelas complexidades da identidade pós-colonial em Goa” é objecto de estudo de Anthony Gomes, no artigo intitulado “Vozes da identidade goesa”. O autor refere-se à literatura mundial que o poeta traduziu para concani; o seu papel no enriquecimento da paisagem literária regional, na promoção do diálogo cultural e na articulação da identidade cultural goesa.

Por sua vez, Júlia Serra foca outro poeta contemporâneo, José Rangel, que reuniu parte da sua obra em Toada da Vida e Outros Poemas. Os seus poemas são de índole diversa: para além do misticismo religioso do Oriente e do dinamismo do Ocidente, há referências a línguas, à procura da identidade, à cultura, à paisagem confrontada com o arranha-céus, à vida nos cabarets; e reflexões sobre o bem e a graça divina, sobre o profano e o religioso, e sobre o amor cantado nas diversas dimensões.

Recuando um pouco, Philomena e Gilbert Lawrence evocam a figura de Luís Vaz de Camões, que em Goa escreveu grande parte d’Os Lusíadas; e traçam paralelos com a vida do eminente Winston Spencer Churchill: foram ambos militares de duas potências coloniais na Ásia.

Ainda hoje continua esse diálogo intercivilizacional iniciado há cinco séculos. Por exemplo, a Fundação Oriente desempenha uma vasta rede de actividades, registadas aqui por Paulo Gomes, seu Delegado em Goa, a oriental Lisboa.

Por outro lado, neste mês, na capital portuguesa, realiza-se LisGoa, um encontro de líderes empresariais de Goa, como destacado no suplemento especial a esta edição.

Não termina ali a panorâmica histórica e cultural de Goa. O conto em concani, ambientado no remoto concelho de Satari, transporta-nos para uma Goa de outrora, dir-se-ia, pré-portuguesa, pois distam muito os costumes desse povo, daqueles que são correntes nas partes cristianizadas de território. “A Árvore de Fruto Amargo”, de Prakash Parienkar, transliterado do concani em caracteres devanagáricos para romanos e traduzido para português pelo editor associado Óscar de Noronha, vai acompanhado também do link do respectivo filme.

Rematamos a apresentação desta edição convidando os leitores à nossa secção de arte. Girish Gujar e Govit Morajkar, respectivamente, em aguarela e pintura, chamam a nossa atenção a dois locais em Goa; o caricaturista Alexyz tece uma crítica aos problemas de Goa contemporânea, enquanto Clarice Vaz e Edgar João apresentam Goa como o eterno idílio.

E não vamos sem registar que na capa desta edição temos a Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Imaculada Conceição, o ex-libris da cidade de Pangim; e na contracapa, o link da Global Goan, nossa Revista parceira, cuja leitura calorosamente recomendamos aos Goanófilos.

-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-

Our minuscule Goa has the power to unfold into several Goas. There is the Goa of history and the Goa of contemporary times, the geographical Goa and the Goa of hearts scattered around the world, the real Goa and the Goa of our dreams. There are, therefore, several Goas. And within each of them are social, economic, political and cultural gears that continue to turn. Those who claim to know them all live out the Indian fable of the Blind Men and the Elephant.

Nonetheless, Revista da Casa de Goa strives to interpret these Goas for its readers. The present edition is a case in point. It begins by talking about Panjim, the poetic capital of Goa, which previously had other names: New Goa and City of Goa. Our associate editor José Filipe Monteiro recounts the interesting story of how in the nineteenth century this modest ward of the village of Taleigão grew into the capital of the Portuguese Oriental empire.

Coincidentally, another associate editor, Valentino Viegas, recalls in his column the “sweet years” he spent in Panjim, and in shorts explored its nooks and crannies. And, how wonderful to suddenly see, side by side, the macro and the micro history of Portuguese India.

However, the living situation in Goa is not all that wonderful. Read the article titled ‘Will Goa be India’s next Ayodhya?’, by Ivo de Noronha. In fact, although known as a model of peaceful coexistence among different communities, and for its strong sense of civic identity, Goa faces a challenge that is as subtle as it is insidious.

In situations like these, it is so heartening to recall, as David Pinto does in his article ‘Globalisation in Goa: The Asian contradiction’, that Goa was indeed one of the first multicultural and global societies of all times. He adds that, even in the 21st century, living in Goa ‘provides an experience different from that in any other part of India.’

This type of pioneering spirit shines through Jesuit priest Richard Anthony D'Souza’s recent papal appointment as Director of the Vatican Observatory. A Goan quite naturally becomes a citizen of the world. In the news section we have more details of that honourable selection.

After all, it is Goa’s centuries-old culture that defines it. Look at Manohar Rai SarDessai, whose ‘role as a cultural hybrid navigating the complexities of identity in postcolonial Goa’ is the object of study by Anthony Gomes in his article titled ‘Voices of Goan Identity’. The author refers to the poet’s translations of world literature into Konkani and his role in enriching the regional literary landscape, promoting cultural dialogue, and articulating the Goan cultural identity.

Júlia Serra, for her part, focusses on another contemporary poet, José Rangel, who compiled part of his work in Life’s Refrain and Other Poems. His poems are diverse in nature: in addition to the religious mysticism of the East and the dynamism of the West, there are references to languages, the search for identity, culture, the natural landscape vis-à-vis the skyscrapers, life in cabarets; and reflections on goodness and divine grace, on the profane and the religious, and on love sung in its various dimensions.

Rewinding a little, Philomena and Gilbert Lawrence evoke the figure of Luís Vaz de Camões, who wrote a large part of The Lusiads in Goa, and they draw parallels with the life of the eminent Winston Spencer Churchill: both were soldiers of two colonial powers in Asia.

This inter-civilisational dialogue, which began five centuries ago, is still on. For example, the Orient Foundation engages in a wide range of activities, listed here by Paulo Gomes, their delegate in Goa, the oriental Lisboa.

On the other hand, LisGoa, a meeting of business leaders from Goa, is due to be held in the Portuguese capital this month, as highlighted in the special supplement to this edition.

The historical and cultural overview of Goa does not end there. The short story in Konkani, set in the remote taluka of Satari, transports us to a Goa of yesteryear, one might say, pre-Portuguese, as the people’s customs there are very different from those in the Christianised parts of the land. Prakash Parienkar’s ‘The Bitter-Fruit Tree’, transliterated from Konkani in the Devanagari to the Roman script and translated into Portuguese by associate editor Óscar de Noronha, also carries a link to the respective film.

To conclude our presentation of this edition, we draw our readers’ attention to the art section. Girish Gujar and Govit Morajkar, in watercolour and painting, respectively, put the spotlight on two locales in Goa; cartoonist Alexyz critiques issues of contemporary Goa, while Clarice Vaz and Edgar João present Goa as the eternal idyll.

And we cannot resist pointing out that our cover features the Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, Panjim’s most famous landmark; and our back cover has the link to Global Goan, our partner magazine, a must-read for every Goa-phile.

Tough Choices

Are you astounded by the ways of the world and believe that the corrupt go unscathed? Well, those who imagine they have God in their pockets are sadly mistaken. Not only has God foretold how we humans will evolve, He has numbered the hairs on our head. Most of all, He has listed, and will one day reveal, our acts of commission and omission.

Consider the prophet Amos, who shines in history as a prophet of social justice. He preached in the northern kingdom, which was at once a place of material prosperity and spiritual ruin. With venality on the rise, the rich were getting richer and the poor, poorer.

To make matters worse, there was there was corruption in the religious sphere too: pagan shrines were mushrooming, idolatry was thriving, and the Chosen People showed a sense of superiority. No wonder, the (false) leaders of the people rejected Amos and his fulminations against Israel and her neighbours; his announcements of divine retribution, and finally even the messianic hope he offered.

Today, in the First Reading (Amos 8: 4-7), Amos warns those who ‘trample upon the needy and destroy the poor of the land’. In contemporary terms, that refers to crooks who snatch bread from the tables of simple, credulous citizens, and rather than be sent to jail are sent to Parliament! Amos also warns those who, in the privacy of their homes or institutions, tell lies, bully and beat, exploit and cheat, drink and debauch, and without any qualms of conscience go out and preach.

In contrast, those who trust in God and work for His kingdom have not a care in the world. As the Psalm states, ‘He raises up the lowly from the dust; from the dunghill He lifts up the poor to seat them with princes, with the princes of His own people.’

So far so good. What is unsettling, however, is that in the Gospel (Lk 16: 1-13) Jesus appreciates the shrewd steward’s efforts to provide for his future. Was the Master commending the ‘dishonest steward’? It may seem so, but it is not the steward’s expediency but his decisiveness that Jesus extols. He indicates how ‘the children of this world are wiser in their own generation than the children of light.’

Who can deny that evil is more active than good and the worldly-wise more diligent than the spiritual-minded? That sounds a clarion call to God’s people to turn dynamic and combative! You and I need to show greater enthusiasm for God’s kingdom and go forward together with our united strength. Letting ourselves be ruled by evil doers is the price we pay for our lukewarmness. What use is it to complain thereafter? That is why Jesus wishes to rouse the honest ones from their slumber and call for resolute action.

Look at our country and our state. What does it profit us to complain about our representatives, when it is we who have elected them? We’d found them dishonest in small ways, hadn’t we, but we looked the other way, didn’t we? When we fail to stand on principle and cling to our foundational truths, we are fated to suffer their dishonesty in big ways!

That is the natural consequence of sitting on the fence. It never pays to sacrifice our principles, our doctrine, on the altar of convenience. ‘No servant can serve two masters… you cannot serve both God and mammon.’ If only children of light were faithful to God as those of darkness are faithful to mammon!...

In the Second Reading (1 Tim 2: 1-8), St Paul urges ‘that supplications, prayers, intercession, and thanksgivings be made for all men, for kings and all who are in high positions, that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life, godly and respectable in every way.’ This feels so topical, yet eternal, doesn't it? It addresses an issue that people across the board feel deep down, even if some don't admit it.

Finally, as Pope Benedict XVI has said, ‘it is a matter of choosing between selfishness and love, between justice and dishonesty and ultimately, between God and Satan.’[1] That’s our ultimate choice in life.

[1] Pope Benedict XVI, Homily, Suburbicarian Diocese of Velletri-Segni, 23 September 2007 https://www.vaticannews.va/en/word-of-the-day/2025/09/21.html

The Cross: our Badge of Honour

Christianity is full of paradoxes. One of them is the Cross, which has been transformed from a symbol of disgrace into a symbol of honour. In the Roman Empire, dying on the cross was a brutal punishment reserved for slaves and lowly criminals; however, through Jesus Christ’s Passion, Death and Resurrection, it became a symbol of hope and love.

On 14 September, we celebrate the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. It is a manifold commemoration: that of the discovery of the True Cross by St Helena on her pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the year 326 AD; the dedication of the church of the Holy Sepulchre built by her son, the first Christian Roman Emperor, Constantine the Great, and consecrated on 13 September 335 AD; and the public veneration of the Cross there the following day.

Much later, Emperor Heraclius won back from the Persian Emperor Khosrow II the True Cross that the latter had captured on the occasion of his conquest of Jerusalem in 614 AD. The Byzantine emperor elevated the said Cross at Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, and later brought it to Jerusalem in 629 AD.

Considering the central role of the Cross in the Christian faith, the Sign of the Cross has become a distinctive gesture of devotion. Christian households usually have a crucifix (a cross with the body of Christ on it) hanging on the wall. ‘Exaltação da Cruz’ (Exaltation of the Cross, in Portuguese) is even taken as a baptism name. All of which speaks of how the Cross is exalted above all other symbols in Christianity.

This year, the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross falls on a Sunday. This happens on an average once in seven years. Hence, a new set of Readings on the 24th Sunday of Ordinary Time of this year.

In the First Reading (Num 21: 4b-9) we see the punishment meted out to the Israelites who had rebelled against God instead of being grateful to Him for rescuing them from slavery in Egypt. They were bitten by fiery serpents, and perished. So, God instructed Moses to create a bronze serpent figurine and hoist it on a pole or staff; whoever looked upon the bronze serpent, survived.

In reality, the bronze serpent was the prefiguration of the Lord Himself, who would hang on the Cross for our sake centuries later. This is clear from Jesus’ words to Nicodemus in the Gospel text (Jn 3:13-17): ‘No one has gone up to heaven except the One who has come down from Heaven, the Son of Man. And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, so that everyone who believes in Him may have eternal life.’

The Ascension would not have happened without His Passion, Death, and Resurrection, all of which was an act of loving reparation for the sins of humankind: ‘For God so loved the world that He gave His only Son, so that everyone who believes in Him might not perish but might have eternal life.’

The Gospel text further states in no uncertain terms that ‘God did not send His Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through Him.’

St Paul makes this clear in today’s Second Reading (Phil 2: 6-11) when he says that Christ ‘emptied Himself, taking the form of a slave, coming in human likeness; and found human in appearance, He humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross. Because of this, God greatly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, of those in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.’

Therefore, we must never feel embarrassed by the Cross. In fact, we must put it back where it belongs: in the Catholic educational institutions that have removed it in the name of ‘political correctness’ and in the clinics and hospitals that have replaced it with the Rod of Asclepius.[i] We must bring back the solid crucifix into our ultramodern churches that have fallen for minimalist crucifixes, or the Risen Christ with the cross in the background, or even just the Risen Christ – as though the Crucified Christ were something to be ashamed of.

Finally, today and always, we must make it a point to exalt the Cross in our homes and in society at large. In concrete terms, we must take up our cross and follow Him (cf. Mt 16: 24). The Cross is the ultimate example of love. We must make it a point to exalt the Cross in our hearts: it is our badge of honour.

[i] The Rod of Asclepius symbol is a medical symbol depicting a single snake coiled around a staff or rod, representing healing, medicine, and the Greek god of healing, Asclepius.

Jesus lambasts hypocrisy

The Bible is not a collection of feel-good stories that might give false hope and ultimately disappoint us. It is a collection of books that reveal God’s sincere and longstanding relationship with humankind. The Word became flesh in Jesus, who then refined the teachings of the Old Testament, making them comprehensible to modern man. For its part, the New Testament is a perfect guide for imperfect people like you and me, helping us to live rightly, as Jesus did.

Take the case of the Book of Sirach, from where the First Reading (3: 17-20, 28-29) is taken. Written circa 180 BC, it is the only book of wisdom literature whose author is known by name: Jesus Ben Sirach, a Hellenistic Jewish scribe. It is warmly recommended for its instruction and edification. Its rich, practical teachings are presented in a fatherly and persuasive manner.

Shining as it does by its supernatural motivation, its advice differs from, say, that of Bacon’s Essays, or Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. So, when Sirach tells you to ‘perform your tasks in meekness; then you will be loved…’, it’s not a manipulative strategy to find acceptance in the world. The words that follow ‘loved’ are important: ‘loved by those whom God accepts.’

In other words, the approach is other-worldly. God’s acceptance or ratification is what matters – an aspect so important to stress upon in an age when ‘anything goes.’ For example, if wanting to pass off as ‘broad-minded’ individuals, elders may fail to reprimand youngsters. Similarly, politicians of all hues bend over backwards to please (and in recent times, even Opposition members have shown much skill in backbends and forward bends). The bend is always on the side their bread is buttered...

As if that wasn’t bad enough, ‘men of God’ have followed suit. And what can be worse than the hypocrisy of the ‘men of God’? Some of them feed off the people’s adulation, while others curry favour with political animals… Just another move, and they’ll have crossed over to the other side and worship false gods. That’s precisely what happened in Goa yesterday (

If we’ve got any self-respect left, our archdiocese ought to feel distressed with the arrival of another edition of the ‘elephantine blunder’ of 2022 https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2022/09/13/elephantine-blunder/

In concrete terms, how can a priest engage in idol worship, imagining it to be some kind of innocuous ‘outreach’? If they argue that ‘those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick’ (Mt 9: 12), for goodness’ sake, where’s the medicine?... When Jesus was invited by shady characters – public sinners – He went, knowing full well that they didn’t have the right intentions. But then, He didn’t jump on the bandwagon; rather, confronting the majority, He announced the Good News straight on. That’s a medicine indeed; if we don’t give out our medicine, we could end up drinking their poison!

In today’s Gospel text (Lk 14: 1, 7-14), Jesus advises us to sit in the lowest place, so that when the host comes, he may say, ‘Friend, go up higher’. This may seem like a tactic to climb the ladder of success in this world, but it’s not! In fact, Jesus wants us to transpose the situation to Heaven. For in God’s eyes, ‘He who exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted.’ This is a lesson in authentic, not false, humility.

Further on, Jesus exhorts us to love and care especially for the poor, the weak, and the voiceless. By advising the Pharisee to invite people such as these, and not the rich and famous alone, to his dinner or banquet, He teaches a lesson in selflessness and total trust in the eternal reward that awaits us in Heaven: ‘You will be repaid at the resurrection of the just.’

None of that is difficult for those who truly believe and trust in the Lord our God. That is also the message of the Second Reading (Heb 12: 18-19, 22-24), which juxtaposes the experience of the old and the new covenants. Whereas formerly God made covenants with His people in the midst of the great theophany of the Sinai (God’s visible manifestation to humankind there), in the latter days God made a covenant in the city of the living God. And where once there was fear, now there is love.

Where, then, is there place for hypocrisy in God's economy? None. In fact, Jesus reserves his harshest condemnation for religious hypocrites, such as the Pharisees. He decries their outward show of righteousness as a "whitewashed tomb" and warns that hypocrites will face severe punishment. Their place, then, could well be Hell.

Who will be saved?

Recently, when Israel began to pound Gaza, in a bid to forcefully occupy it, a quote from Zephaniah 2: 4 came up for discussion: ‘For Gaza shall be forsaken, and Ashkelon a desolation: they shall drive out Ashdod at the noon day, and Ekron shall be rooted up.’ Is the prophecy applicable to the present times?

Gaza is in Palestine; the remaining three cities, in Israel. Israel began its offensive against Gaza last Thursday. Yesterday, Yemen's Houthi forces targeted Ashkelon with drones and missiles. What will happen to Ashdod and Ekron (Tel Miqne), both in Israel? How it will all pan out is anybody’s guess.

Meanwhile, it is curious to note how modern Israel seems keen on rewinding Biblical history in its favour. The country is a far cry from the Biblical Israel. How, then, can they insist on the status quo ante? Canaan was for the Chosen People, an enviable position they lost as a result of disobeying God’s commands down the ages. We Christians, for our part, know that the erstwhile Chosen People’s problems are of their own making…

As the First Reading (Is 66: 18-21) states, the Jewish people had been expected to ‘gather all nations and tongues… that have not heard [God’s] fame or seen [His] glory’. They were enjoined to ‘declare my glory among the nations…’ and bring them ‘as an offering to the Lord, upon horses, and in chariots, and in litters, and upon mules, and upon dromedaries, to my holy mountain Jerusalem.’ How much of this did the Jewish people do to glorify the true God?

Whereas they failed to acknowledge that Jesus is the Son of God, and to go out to the whole world and proclaim the Good News, now they line up, like self-proclaimed heirs and beneficiaries who unashamedly gather after a person’s death, to claim the former land of Canaan as their inheritance. Their gods are Baal and Mammon; their instruments of worship, drones and missiles! That’s the measure of their iniquity.

In the Gospel (Lk 13: 22-30), the Son of God, whom God the Father sent to earth as a final act of redemption, stated in no uncertain terms: ‘Many, I tell you, will seek to enter [the kingdom of God] and will not be able.’ This is a word of caution to all who go on with life as if the earth is their final destination: let them not be alarmed when the hour inexorably strikes! At that point, of what use will it be to say, ‘We ate and drank in your presence, and you taught in our streets.’ He will retort: ‘I tell you, I do not know where you come from; depart from Me, all you workers of iniquity!’

Alas, they will weep and gnash their teeth on seeing Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and all the prophets in the kingdom of God, and be thrust out. Even if pagan nations unite against Jerusalem, God will defeat them and use them for His glory. Thereafter they will share the former privileges of the Jew: ‘Men will come from east and west, and from north and south, and sit at table in the kingdom of God.’ The glorious task of evangelisation will be entrusted to them.

Is Israel, then, fated to perish? My interlocutor pointed out that the Lord says, ‘How can I give you up, Israel? How can I abandon you?... My heart will not let me do it. My love for you is too strong.’ (Hos 11: 8) For sure, we have a most faithful and loving God; He is just and full of mercy. The book’s narrative arc maintains that even if God’s people had deserted the Lord, in the end God’s constant love would prevail and win the nation back to Himself, restoring the relationship. This has been the message of prophets like Jeremiah and Ezekiel, too.

But can the Lord be put to the test? It is futile to think that God being so good will not condemn us definitely. After all, Hell is for the condemned. Why can’t Israel, too, learn a lesson or two from the centuries gone by? They – and we – would do well to take a leaf from the Second Reading (Heb 12: 5-7, 11-13): ‘Have you forgotten the exhortation which addresses you as my sons? … My son, do not regard lightly the discipline of the Lord… The Lord disciplines every son whom he receives… For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant; later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.’

The kingdom of God belongs to such as these who will let themselves be disciplined by the Lord our God. They will show love; they will be grateful; they will serve and be saved.

The Peace We Seek

A prophet finds no acceptance in his own home or country. It could be so for many reasons, one being that true prophets speak the full truth. They do so to guide, warn, or offer hope. But, as the saying goes, the truth hurts, and the prophets end up alienating people. And if they be rich and powerful people, prophets will soon be at the receiving end of all sorts of punishments. It has been so since times immemorial, and is true even in our world that swears by openness, transparency and democracy.

It is therefore not surprising that the prophet Jeremiah in the First Reading (Jer 38: 4-6, 8-10) suffered what he did at the hands of the powers-that-be. It was the year 588 BC, when the king of Babylon had besieged the holy city of Jerusalem. God’s spokesman, finding it suicidal to resist the enemy, advised the country to surrender. His message, however, was not music to the ears of the political leaders. They first tried to prevent him from being in touch with the people. Then, egged on by the puppet king Zedekiah, they condemned him to death. Zedekiah was fated to be the last king of Judah before its destruction by the Babylonian Empire.

Meanwhile, Ebedmelech the Ethiopian prevailed upon the king to reverse his decision. Accordingly, Jeremiah was lifted out of the miry cistern of Malchiah. Ebedmelech, whose name meant Servant of the King, was evidently a believer in Israel’s God. He was an honourable man, the likes of which are rare. Really, how many men of character like the African who saved Jeremiah can we find in our midst today?

Alas, crisis of character is the bane of our times. There is an undeniable decline in moral principles and ethical behaviour, and a visible erosion of trust in institutions and leaders. Those in power are expected to protect and save, but they turn into predators instead. Their egoism and greed has become the defining characteristic of our days. Was it because we have had it easy for too long that we have even forgotten God our Provider? As Michael Hopf, a US Marine veteran, puts it memorably in his book Those Who Remain: ‘Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. And, weak men create hard times.’

‘Strong men’ is obviously what Our Lord wants to make of us when in the Gospel text (Lk 12: 49-53) He declares: ‘I have come to cast fire upon the earth… Do you think that I have come to give peace on earth? No, I tell you, but rather division.’ This again is not good news to our generation that is so accustomed to sermons on forgiveness, love and peace alone, not war and retribution.

Could Our Lord ever be wrong? He spoke of ‘division’ in lieu of ‘peace’. Does that seem incompatible with Our Lord’s title of ‘Prince of Peace’? Fr Anton Huonder, Jesuit missiologist, ascetical writer, and renowned preacher of The Spiritual Exercises, states: ‘Certainly, the Saviour wanted to bring peace to men of goodwill, those who submit themselves to the yoke of His law; He wants to give them, not the peace that the world dreams of, but His peace, which the world cannot give.’ Hence, neither at home nor in society should we aim to please everybody, satisfy all tastes, wear a mask, make a pact with error and vice, harmonise irreconcilable dissonances. Instead, we must look for an authentic expression of peace, which is in keeping with God's law.

For that matter, in the world of politics, can we go by the promises of peace made by leaders, be it Trump or Putin, Netanyahu or Khamenei? Look at how ‘Pursuing Peace’ melted down in Alaska yesterday. The peace our statesmen present is not true peace; they neither know nor wish to know how to achieve it. It suits them to pose as ‘pacifists’ whereas all they ever want is personal glory and (maybe) monetary advantages for their country. The late Brazilian Catholic thinker Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira clinched it: ‘Peace [is] a cause much too beautiful, much too just and much too noble to be left in the hands of pacifists.’

To conclude, there is nothing else left for us to do but to ‘run with perseverance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before Him, endured the Cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God.’ That’s the message of the Second Reading (Heb 12: 1-4) today. And there is none else that we can trust but Him who gave Himself up for our salvation.

Jesuit Fr Douglas Rowe’s hymn puts it very heart-warmingly: ‘No one can give to me that peace which my Risen Lord, my Risen King can give’. Indeed, that’s the one and only peace we ought to seek.

Faith conquers all

It is sad how in the world today human reason or knowledge rather than faith in God is generally at the top of the order. Accordingly, people of faith are perceived as weak while those with worldly knowledge are celebrated. People with minds trusting in human agencies strut around as if they have seen it all, done it all. Thankfully, today’s Readings lend us a fresh perspective.

In the First Reading taken from the Book of Wisdom (18: 6-9), the writer refers to the fact that Abraham and his descendants were aware of the night when their people would be freed from slavery in Egypt. That night would mark the ‘deliverance of the righteous and the destruction of their enemies’. But then, did they acquire that knowledge on their own merits? No; it was revealed to them by God, because of their faith in Him.

In whatever we do, whether big or small, we must rely on divine providence; pray, and give thanks at all times. For their part, the Israelites offered sacrifices ‘in secret’, in the privacy of their homes. But that was not all. With one accord they agreed to abide by the divine law and were ready for ‘blessings and dangers’ alike. Life would be less stressful life if we too, as per the Ignatian formula, prayed as if everything depended on God and worked as if everything depended on us. ‘God knows best’ could well be our motto.

It is this type of faith that the Second Reading (Heb 11: 1-2, 8-19) defines as ‘the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.’ That is how our ancestors lived: always trusting in the Lord. That is how Abraham went out and lived in a foreign land, no questions asked; and Sarah, though sterile, received power to conceive. When a sense of adventure and openness is informed by a deep faith, God makes the seemingly impossible possible!

In fact, in chapter 11, the writer revisits the whole of salvation history from the faith perspective. He also introduces us to a number of individuals and events that bear out the power of faith. That is not to say that having faith frees us from trouble, sickness, criticism, attacks, danger, and the like. What it really does is strengthen us in the belief that, no matter what happens, we enjoy the benefit of God’s protection.

Similarly, all that we have prayed for or expected may not happen on earth. After all, we are exiles in this valley of tears. So, it is in Heaven, a ‘better country’, our final destination, that we shall receive our eternal reward. Heaven is the place God has prepared for us, just as He once prepared the Promised Land of Canaan for His Chosen People. Thus, setting our eyes on Heaven is not escapist but realistic; no wonder it ensures health of mind and body.

In that regard, the opening words of the Gospel text (Mt 12: 32-48) carry a hugely refreshing message to our world drowned in anxiety: ‘Fear not, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom.’ So, let's not to rely on what the world has to offer; let's not to set our hearts on things that do not satisfy! Instead, ‘let your loins be girded and your lamps burning, for the Son of man is coming at an hour you do not expect.’

The said Gospel chapter has a series of parables on Our Lord’s exhortation to vigilance. We have to wait for the Second Coming, bide our time, and keep the faith. Such advice is ingrained in our religion. Therefore, however learned we may be, or no matter what we have achieved in life, there is nothing comparable to divine power and providence. As A. G. Sertillanges (1863-1948), the redoubtable French Dominican priest, philosopher, and apologist, puts it, ‘Reason ambitions only a world; faith gives it infinity.’ Indeed, faith conquers all.

Banner: https://shorturl.at/PIB5u