Easter, a joy for ever

After a slew of emotions that we experienced through the forty days of Lent, finally that time of the year has arrived when we have much to rejoice over! The Lord is risen: it’s Easter! Alleluia!

How did the Resurrection come to be called ‘Easter’? The ninth-century monk Venerable Bede says the name derives from Eostre, the spring month named after the pagan goddess of fertility. Others say the root of ‘Easter’ goes back to Old English, with a Germanic root related to the cardinal direction East, and yet others point to the Latin aurora, dawn. So, ‘Easter’ is only a colloquial substitute for ‘Pasch’! Be that as it may, Lent is indeed be a springtime for the soul and, if Christ be the Sun, Easter is easily a new dawn for the Christian world.

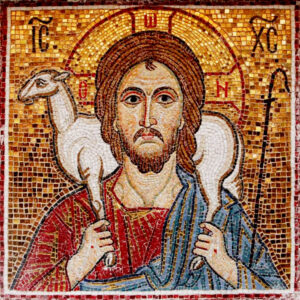

But, hugely more important than etymology is Christ We know that Christ was on a visit to the City of David, to celebrate the Jewish Passover, when He was summarily arrested and crucified. Looking back, there was no longer any use for the animal sacrifice: Christ Himself had become the Paschal Lamb. Then, with His glorious Resurrection on the third day, He introduced humankind to a New Passover, which we call Pasch or Easter.

We know that Christ was on a visit to the City of David, to celebrate the Jewish Passover, when He was summarily arrested and crucified. Looking back, there was no longer any use for the animal sacrifice: Christ Himself had become the Paschal Lamb. Then, with His glorious Resurrection on the third day, He introduced humankind to a New Passover, which we call Pasch or Easter.

Whether the ‘third day’ was meant to be a period of seventy-two hours or less is of no consequence! At any rate, the Resurrection was an unprecedented happening. The earth-shaking event established Christ’s divinity and validated all His claims and promises. Humankind had indeed met face to face with the True God. No wonder it led to the establishment of a new religion – Christianity.

Whereas our ancestors in faith met God in person and witnessed the Resurrection, many may wish to know the practical significance of the happening to our day and age. Indeed, to us, Easter is a complete gamechanger; its joy transforms us and the way we look at life. And who can fail to appreciate Christ’s message of love and compassion? Has it not made the world a better place to live in? And although physical suffering proper to the human condition lingers on, humankind has been freed from the oppression of sin.

Finally, Christ’s Resurrection is a guarantee of our eternal salvation and that we will be raised from the dead at His Second Coming. St Paul says, ‘If there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ has not been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is empty and our belief comes to nothing.’ (1 Cor 13-15) Hence, Resurrection is the cornerstone of our faith. Its commemoration is no hollow ritual but a meaningful commemoration; it is not just another day but a watershed in the history of salvation.

We say we are an Easter people and Alleluia is our song! This line attributed to St Augustine and popularised by St Pope John Paul is an apt description of our Christian identity. We are to be recognised not by the dress we wear or the food we eat, but by the way we conduct ourselves – with joy; by the way we treat one another – with love; and by the way we relate to our God – body and soul, with hope, praise and thanksgiving.

Easter brings us hope. With its splendour before our eyes, no matter what the circumstances, Easter is a joy for ever.

From Palms to The Passion

It is interesting to note the Liturgy of the Word on Palm Sunday, also referred to as Passion Sunday. While the first two readings and the psalm – Is 50: 4-7; Ps 21: 8-9, 17, 18a, 19-20, 23-24; Phil 2: 6-11 – remain the same for cycles A, B and C, the Gospel changes from year to year, highlighting the three Synoptics: St Matthew (26: 14-27, 66), St Mark (14: 1-15, 47), and St Luke (22: 14-23, 56), respectively. They give an account of the Last Supper, the Agony in the Garden, the unfair Trial, the Way to Calvary, and the Crucifixion and Death.

Thus, St John is the only evangelist who does not figure on Palm Sunday. The Beloved Disciple – who offers a selective and somewhat different perspective on the Divine Master, more theological and mystical – is very especially reserved for Maundy Thursday (Jn 13: 1-15) and Good Friday (Jn 18: 1-19, 42), besides two weekday readings. While the Gospel of Thursday focusses on the Last Supper, that of Friday is a Passion narrative that begins with Gethsemane and ends with our Lord’s Death on the Cross.

That much for the readings. Now, as regards the designation of the sixth Sunday of Lent: it is officially called ‘Palm Sunday’, recalling the day when Jesus arrived to a hero’s welcome for the Passover in Jerusalem. No wonder, Chesterton’s ‘Donkey’ was ecstatic: ‘There was a shout about my ears, And palms before my feet,’ he said. But what determined the choice of that beast ‘with a monstrous head and sickening cry’, ‘the tattered outlaw of the earth’?

Jesus had walked up to Jerusalem in the past. Although the Synoptics speak of just one Passover, St John states that He celebrated three Passover Feasts in the city of David. Yet, this time he chose to use a donkey, to enter in peace, as a king traditionally did, into a city that was his very own – unlike a conquering king that arrived on a warhorse. Jesus borrowed a colt, which was soon thereafter returned to its owner, fulfilling many Old Testament allusions, the most important being 'Behold, O Jerusalem of Zion, the King comes onto you meek and lowly riding upon a donkey.' (Zech 9: 9)

But what were the crowds so excited about that they should thus cheer Jesus? Pope Benedict XVI, in his book Jesus of Nazareth, states that ‘Jesus had set out with the Twelve, but they were gradually joined by an ever-increasing crowd of pilgrims.’ On the way, the blind Bartimaeus who was cured clinched it; he became a fellow pilgrim on the way to Jerusalem. The miracle filled the people with hope that Jesus might indeed be the new David for whom they were waiting.

Jesus was not going to re-establish the Davidic kingdom – far from it! He had always said that his kingdom is not of this world. Yet, the disciples’ act of enthusiastically seating Jesus on that beast of burden was ‘a gesture of enthronement in the tradition of the Davidic kingship’; the pilgrims who, infected by that enthusiasm, joined in spreading out their garments and waving out palms, mirrored a tradition of Israelite kingship; and their exultant cries, though reported differently by the Evangelists, all point to the Old Testament. Still, those players were blissfully unaware that they had fulfilled the Scripture.

The most important part of Scripture, however, was played out by Jesus Himself. He who had come to celebrate the ‘Passover of the Jews’, as the Synoptic Evangelists call it, was in truth observing ‘the Passover of His death and Resurrection’, as St John the Evangelist puts it, for this is what the Saviour said to His disciples: ‘I have been very eager to eat this Passover meal with you before my suffering begins. For I tell you now that I won’t eat this meal again until its meaning is fulfilled in the Kingdom of God.’ (Lk 22:15-16). Jesus fulfilled the Passover by becoming the Sacrificial Lamb.

Our Saviour’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem quickly led to His sorrowful Passion on Calvary. And that is how ‘Palm Sunday’ becomes synonymous with ‘Passion Sunday’ in the Liturgy of the Word.

Has our Lenten spirit slackened?

Is the deletion of Passiontide from the liturgical calendar a sign that our Lenten spirit has slackened? Do we therefore need to step up our acts and symbols to drive its point home?

The fifth Sunday of Lent was traditionally called ‘Passion Sunday’, marking the beginning of ‘Passiontide’. During this two-week long period, which comprised the ‘first’ and ‘second’ Passion Sundays, the Church would intensify her preparations for the Holy Triduum and Easter celebrations. However, with the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council, ‘Passion Sunday’ was practically done away with; the name is, at best, second to the official designation ‘Palm Sunday’, which marks the beginning of Holy Week.

Thus, not only Passiontide as a distinct liturgical season within Lent but, eventually, even the term ‘Passion Sunday’ came to be abolished. This was done ostensibly because the notion of the Passion, that is, the suffering and death of Jesus Christ, is already contained within the forty days of Lent. It was also thought to be potentially confusing and distracting to have a season within a season.

Critics of the abolition, however, point out that such an approach is not consistent across the 1970 Roman Missal, for instance, at Advent.[1] They also opine that ‘the overly-rationalist logic of the [post-Vatican liturgical] reform came up against the traditional piety and practice of the Church.’[2] Even so, from Monday of the fifth week of Lent onward, the Church tries to preserve the liturgical and devotional intensity of the old Passiontide through liturgy, hymns and rubrics, but refrains from explicitly stating so.

Critics of the abolition, however, point out that such an approach is not consistent across the 1970 Roman Missal, for instance, at Advent.[1] They also opine that ‘the overly-rationalist logic of the [post-Vatican liturgical] reform came up against the traditional piety and practice of the Church.’[2] Even so, from Monday of the fifth week of Lent onward, the Church tries to preserve the liturgical and devotional intensity of the old Passiontide through liturgy, hymns and rubrics, but refrains from explicitly stating so.

This goes to prove that there is an unstated need for intensification of the Lenten fervour over a period longer than just a week. Earlier, the most obvious example of a more sombre mood was the veiling of statues and images, which remains an optional practice in the current Roman Missal. Another was the feast of the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary on the first Friday of the Passiontide, now transferred to September. Various other practices occurred during the final two weeks of Lent, such as Stations of the Cross and the Tenebrae services. In short, Passiontide was meant to be a special penitential period where the faithful focussed more intensely on Jesus’ bitter passion and fostered in us sorrow for our sins.[3]

Meanwhile, the traditional Roman Missal (as well as several other Christian denominations) observes this special time in the Church’s calendar quite austerely. It is one of the many treasures of the traditional rite that can be regarded as a feast for the soul; their solemnity, beauty, and spiritual benefits are undeniable. As part of the ongoing reassessment of the liturgical reforms, Pope Benedict XVI, himself an architect of Vatican Council II, states:

‘In the history of the liturgy there is growth and progress, but no rupture. What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful. It behoves all of us to preserve the riches which have developed in the Church’s faith and prayer, and to give them their proper place.’[4]

In times gone by, civil law would unite with Church law to ensure that the faithful understood and gave due importance to Lent. Today, the secular world unites with watered-down ecclesial practices, wittingly or unwittingly making sure that only a few consciously live through Lent. Our bustling lifestyles and the dazzling city lights conspire to dish out utterly Godless experiences that leave us morally and spiritually crushed – ‘snuffed out like a wick’.

But let us not be disheartened. Let us devise a Lenten routine that will advance our individual and collective spiritual growth through spiritual reading, appropriate music, meditation, prayer, confession, the Holy Eucharist, fasting and almsgiving. Let not the Passiontide ebb within us. And then, in a couple of weeks, when we look back on how we had let the austerity of Lent wage war on our sensual appetites, we will surely feel a regeneration of body and soul, and what is more, witness the birth of an authentic joy with which to welcome the feast of Easter.

[1] Special Mass propers were assigned to the last few days of Advent (17th-24th December), to give extra emphasis to the end of this season and assist the faithful to prepare for the celebration of the Lord’s first coming. Clearly, the Council did not think this extra emphasis affected the unity of Advent, or could have been confusing for the faithful. Why, then, did they think that keeping Passiontide would affect the unity of Lent or be confusing? Cf. https://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2021/03/the-fate-of-passiontide-in-post-vatican.html Accessed 2 April 2022

[2] https://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2021/03/the-fate-of-passiontide-in-post-vatican.html Accessed 2 April 2022

[3] https://aleteia.org/2017/03/30/what-is-passiontide/

[4] Benedict XVI, Letter on the occasion of the publication of the Apostolic Letter “motu proprio data” Summorum Pontificum, on the use of the Roman liturgy prior to the Reform of 1970. 7th July 2007 (http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/letters/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_let_20070707_lettera-vescovi.html) Accessed 2 April 2022

[Banner: Dreamstime.com]

God’s Infinite Love and Mercy

The readings of the fifth Sunday of Lent (Is 43: 16-21; Phil 3: 8-14; Jn 8: 1-11) invite us to be humble, show love and mercy to our neighbour and, in turn, experience God’s loving kindness. They illustrate the same challenge and hope that we daily encounter in the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.’

Who can deny that by our modern, rationalist approach to life we are easily given to pride and pessimism? This is the bane of our times. But, as Christians, we cannot allow ourselves to lose hope; the Israelites hoped in God and He rescued them from Babylon. And does He not rescue us from the vagaries of our individual and collective lives? He is a great, big, wonderful God, always opening up 'a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert.' He bids us to refrain from dwelling on the past, on the things of old; he wants us to become a new people, for whom He will do marvellous new things.

It is obvious that God is not dead; He is present in history and continues to fulfil His work of salvation in the Church and the world at large. He knows each and every one of us so intimately and loves us so tenderly that only an unfeeling person will fail to reciprocate. For his part, St Paul says, ‘Once I found Christ, all those things that I might have considered profit, I reckoned as loss… garbage.’ The Apostle of the Gentiles employs superlatives only to better express the absolute value that is Christ, the Son of the Living God.

Knowing Christ is by far the highest ideal that a Christian can desire. It is not a mere intellectual knowledge of Him but a personal relationship with Him. that. Notice how Saul who was once a persecutor of Christ turned out to be one of His greatest advocates, Paul: he who was a sinner was completely transformed by his faith in Christ. Likewise, Jesus who has crossed from death to life helps us cross from a life of sin to a life of grace. Let us praise and thank Him for kindly conquering us.

Finally, the Gospel passage: a luminous example of how God welcomes us with arms open wide. The moment He finds even a hint of repentance in our hearts, His healing power is at work in us. The adulterous woman’s dramatic encounter with Jesus is an example of God’s infinite love and mercy. Jesus does not condone her act – ‘Sin no more’, He tells her, in no uncertain terms – but He forgives her fault. Our Creator, who knows best how we are engaged in a hard battle against sin, is always there for us.

What a lesson that is for us who take the moral high ground! Are we not swift to detect the speck in another’s eye while failing to see the log in our own? About the Scribes and Pharisees who brought that woman to Jesus, says Fulton Sheen in his Life of Christ: ‘So set were they on their barren controversy with the Messiah that they did not scruple to use a woman’s shame to score a point.’ That is the bitterest degradation a woman could suffer. The charge being almost irrefutable, how would Our Lord choose between the Law of Moses, which ordered death by stoning, and His own prescription of love and mercy?

It was a tricky matter. The Roman rulers reserved the right to impose a death penalty, whereas by the Mosaic Law an adulterous woman was to be stoned by the people. Which of the laws would Jesus apply to her? Either choice would be an affront to the other. Further, if Jesus had condemned the woman, they would say He was not merciful; if He had condoned her act, He would be contravening the Mosaic law. And what is more, by disobeying this divine directive, He would be negating His own divinity. Hence, their knotty question: ‘What do you say about her?’

As the popular saying goes, ‘Those who live in glass houses should not throw stones.’ Jesus expressed it in more challenging terms: ‘Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.’ Who was fit enough to defend or execute the Mosaic Law? They were sinners, yet accusers; whereas Our Lord, the only Innocent One, refrained from accusing. His mission was to save the soul. He had said in the Sermon on the Mount, ‘Pass no judgement, and you will not be judged, for as you judge others, so will you yourselves be judged, and whatever measure you deal out to others will be dealt back to you.’

Then again, there is the question of gender discrimination (glaring to our modern eyes): what about men involved in that reprehensible act? Why would they go scot-free? These and many other issues only Jesus, who was man and God, could resolve: He had come not to destroy the law but to perfect and fulfil it!

Today, Jesus invites us particularly to check the state of our souls rather than comment on our neighbours’. Let us admit to our sinfulness and be committed to change our miserable lives; and should we wish to fix our broken world, let love, fraternal correction and mercy be our tools. God will then put His finishing touches to our efforts, with His infinite love and mercy.

(Banner: Rubens, 'Christ and the woman caught in adultery')

Our Cause of Rejoicing

Perhaps no other parable is as striking and moving as the Parable of the Prodigal Son. It is the third and last of a set of parables on mercy. The two that precede it are the parables of the Lost Sheep and of the Lost Coin. While these two represent a sinner’s search for the Heavenly Father, the story of the Prodigal Son shows how the Father searches for and receives a contrite sinner – not commending his sins, for sure, but forgiving them. That is why the parable strikes a chord with everyone.

The Parable has been variously titled the ‘Parable of the Two Brothers’ or ‘Two Sons’ or yet the ‘Lost Son’. But that is to look merely at the human side of the story. By thus limiting its scope we are likely to turn a deaf ear to the true message of what is by now a very familiar tale. So, it is hugely important that we look at it as a harbinger of hope and joy.

Hope and joy cannot spring from, or be sustained by, human endeavours alone. For instance, despite the inherent drama of the parable in hand, it would be just another story if divested of its divine radiance. It is, therefore, not farfetched to alternatively title it the ‘Parable of the Loving Father’ or of the ‘Forgiving Father’ – or even of the ‘Prodigal Father’, in the best sense of the term, that is, one who loves bountifully! After all, divine love and forgiveness are ever-fresh even two millennia after Jesus made it known.

The present parable tells of the younger of the two sons who, by demanding the share of inheritance due to him, infringed tradition and offended his father. He squandered his wealth in loose living and, only when in dire straits, retraced his steps, mentally prepared to work as a servant in his father’s house. Much against his expectation, his father not only welcomed him with open arms but also treated him as a beloved son – as if nothing had happened. No doubt the mother is sorely missing from the scene; but perhaps that is only to show her love is encompassed in God's omnipotent goodness.

It is obvious that the young man considered that he deserved stringency, not mercy. On the other hand, Pope John Paul II, in his encyclical Dives in Misericordia, says that his father’s joyful response indicates that ‘even if he is a prodigal, a son does not cease to be truly his father's son; it also indicates a good that has been found again, which in the case of the prodigal son was his return to the truth about himself.’

What a soul-stirring finale that would have made except that the elder brother literally spoilt the party. On the face of it, he was not wrong. Had not the Benjamin received his share and left the father’s house merry as a bird? Had not his actions disgraced the family? While this is undeniable, is it not equally true that the habitually decorous elder brother was now being self-righteous, resentful, selfish, jealous, and merciless? He may have adhered to the letter of the law, but not its spirit!

We can identify ourselves with the Parable because we are like either of the sons. The Encyclical notes that the younger son ‘in a certain sense is the man of every period, beginning with the one who was the first to lose the inheritance of grace and original justice.’ We may smugly condemn the younger one – he has done something awful that none can accuse us of! We do not forget his flaws, much less appreciate his regrets. We fail to thank God that no such slip-up has landed us in a bad situation. We fail to realise that we ‘all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God’.

The good news is that we can change it for the better if we walk back towards our father – the only perfect character in the Parable. He was sinned against by both his sons, but holds it not against them. He represents God the Father who is always happy to find His lost sons – you and me; and to call upon others – symbolised by the elder son – to partake of that joy. The Parable is a fitting response from Jesus to those who had criticised Him for accepting tax collectors and other public sinners at His table. But then, had God kept a record of our sins, who would survive? So, let’s go ahead and ‘forgive those who have sinned against us.’

That God treats us with love and mercy calls for great rejoicing; it is a crowning of our poor little spiritual journey. That is why the fourth Sunday of Lent is called Laetere Sunday, from the words ‘Laetare Jerusalem’ (‘Rejoice with Jerusalem’, Is. 66:10) in the Latin introit for the Mass of the day. This is a refreshing change in the midst of the sombre mood of Lent. That the Gospel has revealed the Father’s infinite love and mercy and the possibility of our reconciliation with Him and our neighbour is the ultimate reason for our joy.

Três poemas de R. V. Pandit

À espera de Rama

As minas Fizeram de Goa Não sei o quê. As pedras Em ouro transformadas? Não sei. Mas uma coisa eu sei – Homens, que anos atrás Eram de oiro, Hoje estão feitos pedras Como a Ahilia[1] À espera de Rama!!

Inimigos pela língua?

Tu e eu Irmãos somos… Inimigos tornámos23 Por causa da língua!

O Goês

Homem de Goa Tu és como a jaca Com uma coroa de espinhos Como Jesus Cristo. Mas por dentro são bagos Cheios de mel, de amor. Tu és assim! Tu és assim Ó homem de Goa.

A poesia de Raghunath Vishnu Pandit (1917-1990), conhecido como R.V. Pandit, é caracterizada pelo uso do verso livre; e, pela objectividade no tratamento do assunto e economia da linguagem, torna-se, às vezes, aforística.

A poesia de Raghunath Vishnu Pandit (1917-1990), conhecido como R.V. Pandit, é caracterizada pelo uso do verso livre; e, pela objectividade no tratamento do assunto e economia da linguagem, torna-se, às vezes, aforística.

Escreveu os seguintes livros de poesia: Ailem toxem gailem [Cantei tal como senti]; Mhojem utor gavddiachem [Falo tal como um gauddi[2]]; Urtolem tem rup dhortolem [Formas que ficam]; Dhortorechem kavan [Cântico da terra]; Chondravoll [A Lua][3]; e, mais tarde, Reventlim Pavlam [Passos na areia], Lharam [Ondas], além de livros de prosa. A sua obra demonstra entranhado amor a Goa e marcado interesse pelo bem-estar dos extractos mais desfavorecidos da sociedade goesa.

Dedicando-se ao estudo do folclore, publicou dois volumes de histórias tradicionais concanins – Gôdd gôdd kanniô [Contos doces] – e uma versão para crianças de alguns episódios do Ramaiana e Mahabarata. Em 1975, o seu livro Doriá Gazota [O Rugir do Mar] ganhou o prémio da Sahitya Akademi (Academia indiana de Letras). Em 1982, foi recipiendário do galardão Padma Shri do Governo da Índia.

Como fotógrafo amador, Pandit captou de forma excepcional a vida de Gandhi, de quem era sequaz. Foi sócio efectivo do Instituto Menezes Bragança, em Goa, e recebeu o grau de doutor honoris causa de três universidades.[4] É um dos poucos poetas da língua concani e marata com obras traduzidas em português e inglês.[5]

Segundo A Literatura Indo-Portuguesa,[6] de Vimala Devi e Manuel de Seabra, os poemas de Pandit eram vertidos para português pelo próprio; no entanto, todos que encontrámos são da tradução de Mucunda Quelecar[7]; e a tradução inglesa da autoria de Thomas Gay[8]. Na transliteração para caracteres romanos dos seus poemas, que escrevia em devanagárico, teve a ajuda do jornalista Felício Cardoso.[9] E a tradução livre transforma-nos todos em novos poemas.

As três peças que figuram acima tratam de temas candentes do período pós-1961:

O primeiro poema refere-se à transformação da vivência goesa na sequência da exploração das minas de ferro e manganês, a que se procedeu, vigorosamente, a partir dos anos sessenta do século XX. Só após algumas décadas é que o território se apercebeu das nefastas consequências da actividade mineira.

O segundo é um poemeto com um quê de autobiográfico, pois no movimento que precedeu ao histórico Opinion Poll (escrutínio da opinião), em 1967, Pandit bateu-se pela integração de Goa no estado vizinho do Maharashtra de língua oficial marata. Foi por isso hostilizado por escritores goeses da língua concani que eram a favor de estatuto político independente para Goa dentro da União Indiana.[10] Essa rotura com os “irmãos” do idioma goês ter-lhe-ia inspirado esse poemeto.

O terceiro poema é o seu cântico de louvor à índole do povo goês.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Ahilia petrificou-se quando amaldiçoada pelo marido Gautama, tendo mais tarde mudado de estado com um simples toque dos pés de Rama, príncipe de Ayodhya e herói do poema épico Ramaiana.

[2] Os gauddi, considerados os mais antigos habitantes de Goa, provêm da raça proto-australóide.

[3] Edições de autor, publicadas no mesmo dia (26 de janeiro de 1963), em Goa.

[4] Embora a sua habilitação académica não passasse do bacharelato em Letras (B.A.), recebeu esse reconhecimento de universidades filipina, brasileira e americana (Cf. António Pereira, The Makers of Konkani Literature (1982), p. 230; Konkani Vishvakosh, Vol. II, p. 629).

[5] Voices of Peace (Goa, 1967) e The Tamarind Leaf (Goa, 1967). Os seus poemas em tradução portuguesa estão compilados nos n.ºs 119 (1978), 122, 123 (1979) do Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança.

[6] Lisboa: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1971.

[7] Segundo informações prestadas por Madhav Borcar, poeta goês da língua concani, Mucunda Quelecar (1904-?) (vulgo Mukund[a] Kelekar) tinha conhecimentos profundos do concanim, português, francês, latim e inglês. Escrevia regularmente para O Heraldo e A Vida e, em inglês, para The Navhind Times. Foi professor de português e de matemática num liceu particular em Pangim. Traduziu para o concani os contos de Stefan Zweig.

[8] Thomas Gay, de nome completo, Thomas Edward Waterfield Gay (1905-2001) (sendo este último o apelido de sua mãe, adoptado em 1955), alto funcionário do Quadro dos serviços civis britânicos na Índia (Indian Civil Services, ICS). Segundo nos disse Borcar, Gay limava os poemas traduzidos por Pandit em inglês.

[9] Informação prestada por Borcar. O contista e jornalista Felício Cardoso (1932-2004) lançou as bases da nova sintaxe do concani, no período do pós-1961. O seu jornal Sot fundiu-se com o diário A Vida, formando, mais tarde, o jornal Divtti, de que Cardoso foi director associado.

[10] Informação prestada pelo padre Mousinho de Ataíde.

Reconhecimento: Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisboa, Série II, No. 13, Novembro-Dezembro de 2021

Encounter with God

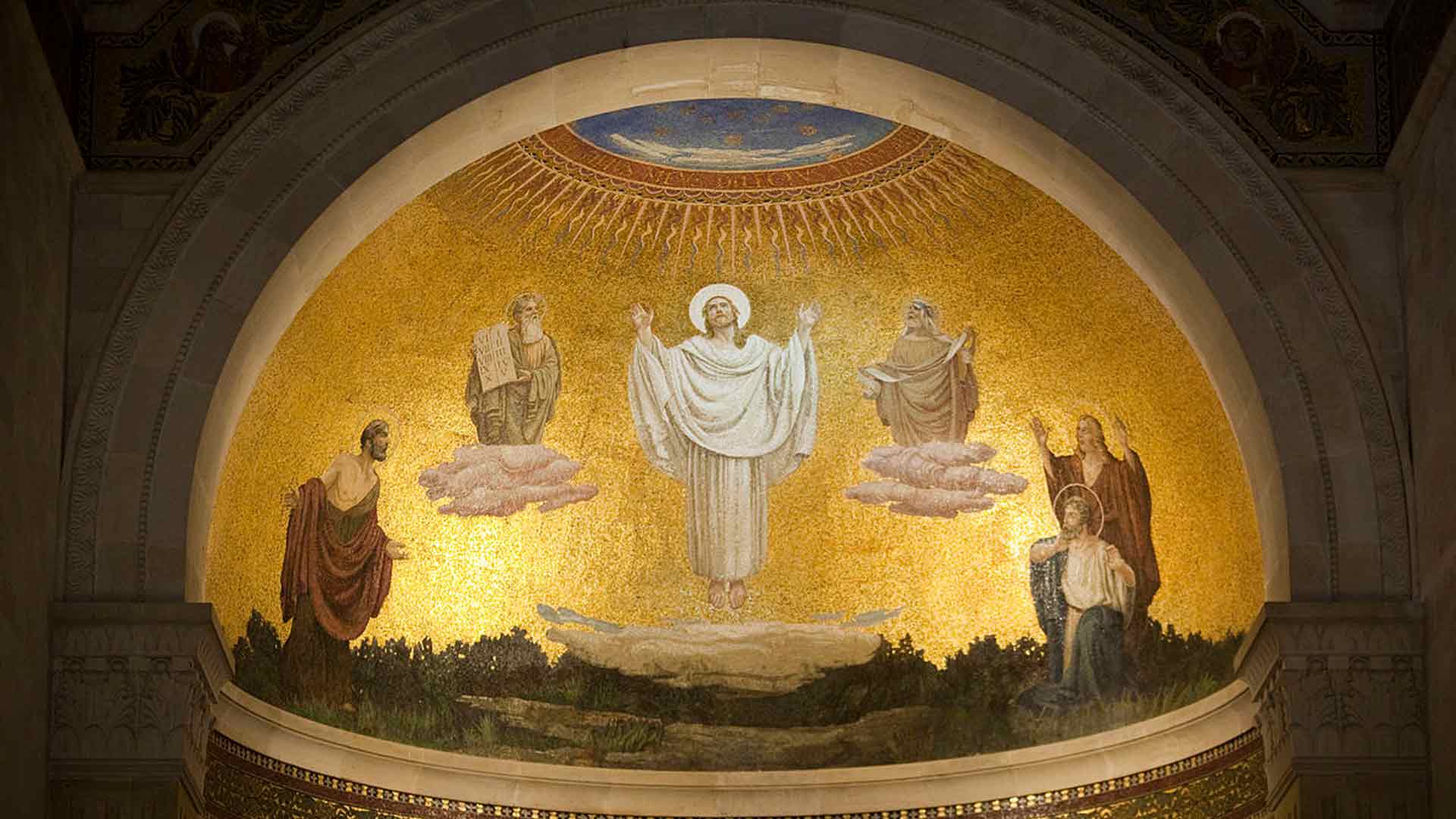

The Gospels of the first two Sundays of Lent were devoted to the Temptation in the Desert and the Transfiguration: in the former, the Son of God laid bare His spiritual fibre, while in the latter, the Father expressed His total trust in His Son. Convinced that we have seen the True God, we today focus on the need for an ever-closer encounter with Him.

God has chosen you and me to follow Him; it is up to us to respond. Moses did so by approaching the burning bush; and on behalf of doubting Thomases of all times, he bade God to better identify Himself. God called Himself ‘I am’ – employing a simple but remarkable verb that pinpoints the core of existence. Closer to our times, French philosopher Descartes famously declared, ‘I think, therefore I am’; which A L Thomas presented as: ‘I doubt, therefore I think, therefore I am.’

Be that as it may, God’s description strikes much deeper: ‘I am who I am.’ You can’t push the boundaries any further. That is because God was present at the beginning of time; He is present now, and ever shall be. In fact, He it is who made Time with a capital T – and, very tenderly, still makes time for us every day! He revealed His greatness and transcendence to Moses but was never aloof. On the contrary, sensitive to the problems of the Israelites, He liberated them from their desperate situation in Egypt.

But if you’ve been wondering why He doesn’t do the same in our day and age – see how criminals have a field day, and despots, none to question them! – be sure that God has not abdicated his responsibilities; He is in our midst and keeps His promises. Chances are we fail to see God in everyday happenings – in the bustle of lives, we hardly make time for Him!

Jesus is the new and greater Moses. He is the Son of God who has spoken to modern man. He is the ‘I am’ variously qualified: ‘I am the Bread of Life,’ He said; ‘I am the Light of the World’; ‘I am the Door’; ‘I am the Good Shepherd’; ‘I am the Resurrection and the Life’; ‘I am the Way and the Truth and the Life’; ‘I am the Vine’. He is indeed the Messiah, the Saviour of the World, always there for us.

How about a closer encounter God! Like Moses, we too will see the burning bush if we care to do a little bit of soul-searching – by believing, hoping and trusting in God; by loving Him, praising Him, blessing Him, glorifying Him, worshipping and giving Him thanks. Constancy in prayer, fasting, almsgiving, and receiving Our Lord in the Eucharist will make of us living tabernacles of God’s Holy Presence.

‘We’ve got a great, big, wonderful God,’ haven’t we? Let’s cultivate a sense of wonder and gratitude! We’ve had the grace to be born in the Christian fold – let’s value our identity! We’re called to be the light of the world and salt of the earth – let’s show it in real terms!

On the other hand, let’s not be reluctant to speak of God and for God. Let’s not fall into the temptation to disown the True God and embrace false gods. It will mean a breach of the First Commandment, a mortal sin, and an outrage crying out to Heaven!

At any rate, every saint has had a past and every sinner has got a future. We are those sinners; we have fallen short of the glory of God. Yet, calamities and disgraces that come our way (be it the war or even the covid-19 pandemic) are not punishments but only a natural consequence of the faulty exercise of our free will. They are at best a heavenly reminder of the urgent need for repentance and inner conversion.

Finally, even if God remains a fascinating mystery to our limited minds, we can rest assured that He is a God who blesses, forgives, heals, redeems and crowns us with love and compassion. With humility, contrition and good courage we can have a change of heart, a deeper union, and a fuller communion with Him who is, was and ever shall be – the Lord our God!

Um punhado de terra

|

(Um conto de Jess Fernandes, traduzido do concani por Óscar de Noronha) História que se passou anteontem à tarde. Veio visitar-me um amigo muito íntimo: Cirilo! Deixara Goa há muitos anos, passando a viver no estrangeiro, onde casou e fez a vida. Como diz o ditado, estamos aí onde nos enchemos a papinha! O rapaz era muito bem instruído. Pretendia trabalhar na sua terra, fazendo algo com as suas próprias mãos. Mas aqui nunca lhe apreciaram os préstimos. Pelo contrário, foi esmagado tal qual uma mosca que pousa sobre a mesa. Quando partia para o estrangeiro, choraram muito os seus pais. Era seu único filho e queriam-no sempre consigo, diante dos seus olhos. Depois de o filho partir, o pai, cismando em como o havia educado e a razão pela qual ele fora embora, fechou os olhos. Os seus últimos sacramentos administrei-lhos eu, José, como se tratasse de meu pai. Cirilo voltou após uns anos de ausência. A mãe não podia conter a sua alegria. E viera com muito dinheiro. Pascu, pai do Cirilo, fora manducar[i]. O terreno à volta da casa, o qual não pudera comprar, comprou-o Cirilo, com o suor do seu rosto. Consertou a casa; e a várzea que a mãe cultivava comprou-a ao mesmo proprietário, além dum pequeno valado que lhe pertencia: fê-lo porque a esse prédio de dois mil e quinhentos metros quadrados estavam ligadas muitas das nossas memórias. Ficávamos aí a brincar, fazendo armadilhas para apanhar passarinhos; e pescávamos no riacho que corria aí perto. Era aí que resolvíamos os nossos grandes e pequenos problemas, partilhando as nossas dores e alegrias. Lá no valado não medravam grandes árvores frutíferas, excepto as seis de mirabolão[ii]. As suas nozes, nunca as colheu o proprietário: comiam-nas os transeuntes. Por isso, fora baptizado de ‘valado dos transeuntes’. Na verdade, estava eu de olho nesse valado. E disso sabia bem o Cirilo. Por isso, antes de falar ao proprietário, consultou-me sobre o assunto. Mas eu reflectidamente disse que não, pois a bagatela que ganhava mal dava para fazer face às despesas. E que ocupação a minha! A de simples amanuense. Também meu pai o era, sob o regime português em Goa; e após a sua morte consegui esse lugar, para o qual o regedor da aldeia, grande amigo do meu pai, propusera o meu nome ao Governo. A mãe de Cirilo fez-se dona da várzea e do valado, porém, poucos anos viveu a desfrutar desse papel. Um certo dia, partiu para onde estava o seu marido na eternidade, e deixando sozinho o filho Cirilo. Após a morte da mãe e até o momento em que Cirilo continuou em Goa, a minha mãe tratou-lhe como filho. E este, quando estava prestes a partir para o estrangeiro, abraçou a minha mãe, e, muito comovido, disse: ‘Mãe, como é que lhe vou pagar todos esses favores? Se o José tivesse uma irmã, far-me-ia seu cunhado. Mas também ele, coitado, é filho único, tal como eu!’ Aquele desabafo tendo cortado o coração à minha mãe, também chorou amargamente. Puxou-lhe para o seu peito e, afagando a sua face, disse: ‘Porque querias ser seu cunhado, meu filho? Tu és irmão dele e meu filho mais novo, querido!’ Nós os três passámos uns momentos a fitar um ao outro e debulhámo-nos em pranto. Antes de partir, o Cirilo confiou a sua várzea a um vizinho e a casa a um primo afastado, a quem pediu que arranjasse inquilino. Aliás, o Cirilo tencionava entregar tudo isso à minha mãe, porém, dada a distância de meia hora que separavam as nossas casas, reconheceu que isso não nos seria possível. Tínhamos uma única várzea e um só prédio ligado à casa. Para além de cuidar dos nossos bens, a minha mãe não tinha possibilidades de zelar pelos interesses do Cirilo. Algum tempo depois de Cirilo ter saído Goa, a família do seu parente passou para essa casa. Escrevi a esse respeito ao Cirilo; e o parente fez o mesmo. Só de pensar que o seu primo iria olhar bem da casa, pois gastara oitenta mil rupias nas benfeitorias, encheu de satisfação o coração de Cirilo. Esta história passou-se há quinze, ou mais, anos. Entretanto, Cirilo deu uma saltada até Goa e, sem pretensões, acabou por casar com uma prima direita minha. Um dia, disse a brincar à minha mãe: ‘Mãe, olhe que ganhei! Não só sou teu filho; até me casei com a filha da tua irmã. Portanto, tanto sou teu filho como teu genro.’[iii] Nem sentimos que haviam passado esses dias de grande alegria. Terminadas as férias de dois meses, Cirilo seguiu para o estrangeiro. Passaram mais uns anos. Nasceram-lhe aí um rapaz e uma rapariga. Era amorosa a sua vida de família e corria-lhe tudo muito bem. No mês de Natal, e no dia em que o céu azul de Goa viu, orgulhosamente, nascer o sol da liberdade, o seu coração pulou de alegria. Cirilo reuniu os goeses da diáspora e dedicou-lhes uma festa. Pensou que Goa e os goeses veriam melhores dias. De quinze em quinze dias escrevia-me a pedir informações sobre como andavam as coisas em Goa, onde não tinha outros interesses senão a sua quinta, a sua várzea e a minha pessoa. Um dia, foram promulgadas em Goa as leis do inquilinato e do mundcarato[iv], as quais mudaram de todo o modo da vida goês. De uma pancada, reduziram os pequenos proprietários a mendigos de rua; e aqueles que o senhorio havia abrigado no seu prédio tornaram-se donos deste. O caso do latifundiário é outro cantar: Deus sabe como eles adqui Lembro-me do que se passou no dia em que apareceram as tais leis. Os meus dois manducares colheram os cocos do palmeiral e venderam-nos sem minha licença. E depois de gozar bem das lanhas, espalharam as suas cascas por todo o lado. Quando lhes arguí, os homens teceram uma filosofia, citando as novas leis, como falsos proprietários de palmo e meio. Depois de me queixar contra eles à polícia, foram manietados. Estiveram presos por quatro dias; foi-lhe sacudido o pó dos seus costados, e foram libertados: esta é outra história! Logo que Cirilo teve conhecimento da nova legislação, regressou a Goa! Mas deixou-se cativar com umas historietas tanto pelo cultivador da várzea como pelo ocupante da sua casa. Um dia, quando passei pelo escritório dum primo, apercebi-me das trafulhices do parente de Cirilo. Longe dele, um empregado dessa repartição contou-me umas anedotas. Informei o Cirilo e fiquei a aguardar a sua chegada. Entretanto, tive de me deslocar de serviço até Delhi, onde demorei um mês e meio. Nesse interregno ouvi dizer que o parente consertara a casa. Quando a visitei após o meu retorno, notei que o homem, gastando rios de dinheiro, transformara a casa por completo. Explicou-me o parente que, como nunca havia pago renda ao Cirilo, empregara esse mesmo dinheiro nas benfeitorias. Mesmo que com essas palavras parecesse decidido a levar tudo, fiquei com certas dúvidas. Dei um relato completo ao Cirilo, urgindo com ele que voltasse logo a Goa. Cirilo chegou precisamente no dia em que estávamos, eu e a minha família, na vila de Mapuçá, a assistir a cerimónia do crisma do meu afilhado. Com umas poucas peças de roupa na maleta, saiu a dizer, ‘Vou a Pangim e volto amanhã.’ Quando voltámos à tardinha, tivemos notícias sobre Cirilo. Aguardei a sua chegada, até às 10 horas da noite. Ontem da manhã não fui ao serviço; também a minha mulher decidiu, de repente, ficar em casa, de licença. Ontem, mais ou menos a um quarto para as seis da tarde, chegou Cirilo à nossa casa. Estava completamente fora de si. Olhando para o seu traje e o seu rosto apercebi-me de muita coisa, pois notei-o a lacrimar. E logo que me viu, derramou lágrimas abundantes. Sem dizer patavina, abraçou-me forte e chorámos os dois. Não foi preciso que me dissesse coisa alguma por palavras. Depois de um grande silêncio, falou. Abriu o seu coração, ficando patente a agitação lá dentro de si: o cultivador da sua várzea tornara-se proprietário! Segundo as novas leis estatais, tinham sido marcados os preços por metro quadrado. Foi uma ninharia o preço que o prédio rústico obteve. Se o pagamento fosse feito de uma só vez, eram trinta e cinco poiçás por metro quadrado; quem o fizesse em prestações, pagava sessenta poiçás por metro quadrado. Ora, não era habitual achar nem sardinha nem arenque por trinta e cinco ou sessenta poiçás; porém, o manducar cultivador acha terreno, ou pelo menos a forma de pagar em prestações. Uns anos antes, Cirilo comprara a mesma várzea por uma rupia o metro quadrado e depois de todos esses anos, qual o preço que cobrou? Receberia pelo menos os juros correspondentes ao dinheiro despendido? Hoje em dia, um agricultor possui ainda sete, ou até oito, várzeas; segundo a lei do mundcarato, a várzea do senhor passou para o manducar. A bem falar, o agricultor devia ter direito a certa várzea ou a uma só várzea, e ainda essa pertencente ao senhor com muitas várzeas. Esse primo tornou-se dono da casa e prédio do Cirilo, tendo já registado os mesmos em seu nome, na Repartição de Agrimensura. Assim, o Cirilo ficou proibido de entrar na sua própria casa, que comprara com tanto esforço! Mal soube da vinda de Cirilo a Goa, o primo contractou uns brigões e capangas e postou-os à porta da casa. Cirilo sentiu-se ameaçado. O primo e um dos maltrapilhos haviam registado o valado dos transeuntes em seu nome. Promulgado o registo na agrimensura, o primo tornou-se dono, ficando claro que a papelada que havia enviado ao Cirilo era forjada. Daqui em diante, para conseguir algo, seria preciso subir e descer os degraus do tribunal… e a justiça, estava ela à mão? Só atravessando sete mares… Com efeito, a lei expulsou um filho amado de Goa e do país. Sentia-se estrangeiro na sua própria terra… Hoje, ao meio-dia, Cirilo recolheu num saco plástico um punhado de terra lá da sua várzea. Curvando-se, e com os olhos cheios de lágrimas, beijou o solo. Depois, despediu-se de todos e subiu para o avião, voo esse que pôs termo à sua relação com esta terra.… para sempre! |

[i] Lavrador que mora, sob certas condições, no prédio rústico dum proprietário.

[ii] Anvalló, em concani.

[iii] Primos direitos são considerados ‘irmãos’, e daí Cirilo ter-se considerado irmão de José e filho da mãe deste.

[iv] O sistema relativo ao manducar.

Notas Biográficas

Jess Fernandes, de nome completo Menino Jesus de Maria Fernandes, nasceu em 1941, em Quepém, Goa. Tirou o 7.֯ ano do Liceu e fez a carreira de paramédico nos Serviços de Saúde, em Goa. É poeta, contista e dramaturgo da língua concani, e autor de 38 livros. Traduziu em concani vários livros do Velho Testamento e espera publicar brevemente a sua autobiografia.

Jess Fernandes, de nome completo Menino Jesus de Maria Fernandes, nasceu em 1941, em Quepém, Goa. Tirou o 7.֯ ano do Liceu e fez a carreira de paramédico nos Serviços de Saúde, em Goa. É poeta, contista e dramaturgo da língua concani, e autor de 38 livros. Traduziu em concani vários livros do Velho Testamento e espera publicar brevemente a sua autobiografia.

Reconhecimento

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisboa, Série II, No. 16, março-abril de 2022

Bridging humanity and divinity

The readings today bring into sharp focus the relation between humanity and divinity. Whereas ‘Christ assumed a true human body by means of which the invisible God became visible,’ (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 92), ‘the human person is the summit of visible creation in as much as he or she is created in the image and likeness of God.’ (63) ‘Endowed with a spiritual and immortal soul, intelligence and free will, the human person is ordered to God and called in soul and in body to eternal beatitude.’ (352) That’s a bridge between humanity and divinity.

Christ who is divine deigned to become human; isn’t it only fitting that we who are human should strive towards the divine? Our fallen condition makes that aspiration seem beyond us. That’s a cross that we have to carry, but we have also to persevere, trusting that the final victory will be ours. In the words of the popular hymn ‘Old Rugged Cross’: ‘I'll cherish the old rugged cross / Till my trophies at last I lay down / I will cling to the old rugged cross / And exchange it some day for a crown.’ That’s when we will have fulfilled our vocation and mission as Christians.

In our pilgrim journey, we are often assailed by doubt. ‘How am I to know that I shall possess [this land]?’ asked Abram. Trials and temptations were his cup of woe, as they are ours today; but he remained faithful to God, and we should do likewise. After all, God extends His hand to us all the time; we should gauge his love and say, ‘The Lord is my light and my salvation.’ A wonderful antidote to all temptations, this psalm should forever be on our lips.

In the second reading, St Paul declares that for many ‘their God is their stomach; their glory is in their shame.' Sounds so contemporary! Indeed, aren’t we anxious about sowing, reaping and gathering into barns? If we think it natural to be ‘occupied with earthly things’, how much more should we be occupied with our supernatural destiny! Being made in the image and likeness of God ‘our citizenship is in Heaven, and from it, we also await a Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ.’ If anyone else claims to speak words of salvation, be sure their ‘fruits [are] like honey to the throat / But poison in the blood.’ We can’t really stomach them, for we are made for God.

Jesus came into the world with the Good News of Salvation. But alas, the people of Israel were deaf to His message and blind to His miracles. On Mount Tabor, disciples Peter, John and James heard Jesus talking in glory to Moses and Elijah. Jesus’ imminent departure from this world was at the top of the agenda, but at the top of Peter’s mind was just the pleasure of being there on the Mount. When a cloud overshadowed the trio, and they were afraid, the Father’s voice spoke these ineffable words: ‘This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to Him!’

The Transfiguration is a major feast in the Catholic Church; is it the same in our hearts? St Thomas Aquinas considered it to be one of the greatest miracles in that it complemented baptism and showed the perfection of life in Heaven. St Pope John Paul II introduced it as a ‘luminous mystery’ in the Rosary. But does the miracle transfigure us – turn us into something more beautiful and elevated?

On that Mount, Jesus became the visible bridge between God and man; do we act as bridges or as walls in our society? God the Father clearly indicated that His Son’s mission is higher than that of Moses and of Elijah. How far have we taken this message to the people around us?

That God appeared in person and spoke live is proof that ours is not a God of the dead but of the living: Moses and Elijah, who died centuries ago, are seen in the presence of God. It is a vindication of the Eternal Life promised to all who die in the faith. What an awesome God we serve. ‘Now more than ever seems it rich to die’!

God's Grace: go get it this Lent!

The secular world has given Lent a bad name by making it look like a season of deprivation. It has artfully concealed the fact that deprivation is a thing of its own making, the outcome of a sinful existence. Isn’t sin rampant and yet seemingly non-existent? In the modern world shattered by sin, alas, the absence of God’s grace is its greatest deprivation.

Against that sordid background, how soothing a balm is the liturgical season of Lent! We are invited to return to God, to walk in His path, and to savour His mercy and love. We ought to seize these forty days and renew our faith in the God who saves. We can never forget that the Father sent his Son to restore His covenant with the world; and that relationship is still alive. Lent is therefore a time of great hope, joy and thanksgiving.

The first reading on this first Sunday of Lent (Year C) is taken from Deuteronomy (26: 4-10), the fifth book of the Old Testament. The book comprises Moses’ sermons to the Chosen People as they stood on the threshold of the Promised Land, after a long exile in Egypt. These addresses recall Israel’s past and assert the identity of the Israelites; they also recap the laws that Moses had conveyed at Mount Sinai, stressing that their observance was essential to the people’s wellbeing.

In today’s excerpt we see that Moses calls the Israelites to offer their first produce to the Lord of Heaven and Earth to whom everything belongs. How deeply pertinent to our day and age! We too ought to offer the best of ourselves to God. Such acts of praise and thanksgiving would be perfect antidotes to modern man’s tendency to pose as all-knowing and all-powerful. It’s time we reset our priorities and put God first in our lives.

In the second reading, St Paul (Rom 10: 8-13) echoes those thoughts. The Son of God is the Saviour of the World. And, clearly, ‘if you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead, you will be saved.’ Thus, Christian faith is about trusting in God’s omnipresence, omniscience and omnipotence; it is about adhering to the Risen Christ. He invites everyone; ‘the same Lord is Lord of all and bestows his riches upon all who call upon Him.’ So, let every knee bow and every tongue confess that Jesus is Lord.

The Gospel (Lk 4: 1-13) shows how the evil one deplored the truth that Jesus is Lord. He thought it fit to test Him in the wilderness after Jesus had suffered deprivation of food, water, sleep, and human company. He was disappointed on seeing that the Son of Man had ample provision of the Spirit of God. But then, why did the Holy Spirit lead Jesus to be tempted at all! He did so that His victory might be even the greater. And behold His rejoinders: ‘Man shall not live by bread alone but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God’ – ‘You shall worship the Lord your God, and Him only shall you serve’ – ‘You shall not tempt the Lord your God.’

Here in India, we would call that a ‘tight slap’. Yet, the temptation in the desert was not an isolated incident; it was very much the beginning of Jesus’ struggle with the prince of darkness, and it only ended on Calvary!... And be sure that the evil one is still around, testing you and me in the tangle of our lives. He tempts us with money and comforts, power and influence; it is almost as if the world is in his clutches. He brazens it out in ways unknown to us naïve children of the light! Not even our baptism in Christ protects us from his icy fingers; the first sacrament is rather the start of a hard journey that tests our faithfulness. But why worry when He is there, ‘My refuge, my stronghold, my God in whom I trust’! (Ps 90: 1-2)

This Sunday of Lent let us acknowledge that the battle with forces of evil is an undeniable reality. (Our hearts go out to the people of Ukraine who have been countering the enemy with fortitude – Amen!) We must diligently put on the armour of God, be filled with the Holy Spirit and stand against the wiles of the devil. We have the sacraments, particularly the Eucharist, which will empower us. For our part, we must renounce evil, sin and Satan – and embrace good, grace and God. Let’s go get it this Lent!

riram esses prédios rústicos de grande extensão! Mas lá porque foi incorrecto um indivíduo não justifica que seja punida toda a sua classe.

riram esses prédios rústicos de grande extensão! Mas lá porque foi incorrecto um indivíduo não justifica que seja punida toda a sua classe.