A Goan at the UN

Seminário Patriarcal de Rachol salva precioso património

O edifício do Seminário Patriarcal de Rachol da Arquidiocese de Goa, construído pelos jesuítas no século XVII, guarda um precioso património. Em algumas das suas robustas paredes encontram-se pinturas que retratam cenas bíblicas, a vida dos santos, e elementos da doutrina católica. São reproduções de quadros de artistas renascentistas: Rubens, Rafael, Miguel Ângelo e Caravaggio.

Outras pinturas dizem respeito aos Patriarcas da Arquidiocese e a fundadores de ordens religiosas. Vêem-se também obras de Ângelo da Fonseca, conhecido como o “Pai da Arte Cristã Indiana”.

Trata-se de mais de 150 pinturas executadas por artistas locais entre os séculos XVII e XX, em três formas: frescos, telas e óleo sobre madeira.

Por falta de recursos humanos e financeiros, essas pinturas foram deteriorando ao longo dos tempos. A partir do ano de 2017, graças à iniciativa do Reitor Dr. Padre Aleixo Menezes e à boa-vontade de Caterina Goodhart, directora da Escola de Conservação de Quadros e Molduras, de Londres, vários goeses e estrangeiros por ela treinados, ajudaram a restaurar as obras de arte, no âmbito do projecto intitulado “Restauradores sem fronteiras”, iniciado pela profissional londrina.

Até hoje estão restauradas as seguintes pinturas e imagens:

- Retratos dos Patriarcas Mateus de Oliveira Xavier, Teotónio Vieira de Castro, José da Costa Nunes e José de Vieira Alvernaz;

- Tela da autoria do general José Francisco de Assa, a qual retrata o Rei Dom Sebastião, que facultou a construção do Seminário;

- Uma outra, setecentista, representando a levitação de S. Francisco Xavier, no acto de administração da Sagrada Comunhão;

- Retratos de Maria Madalena, Santo António e o Menino Jesus, em estilo flamengo.

As obras do Seminário não só valem em si mas também por serem trabalhos de artistas locais. Reforçam a história e identidade artística do território, além de serem um óptimo meio de transmitir a Fé. Nas palavras do padre Victor Ferrão, professor do mesmo seminário, são elas uma “imagem do céu na Terra” e constituem uma “Bíblia visual” nas paredes.

(in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Fev de 2021)

Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

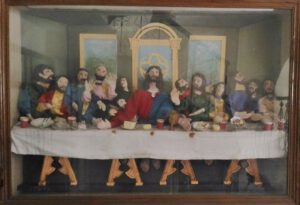

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

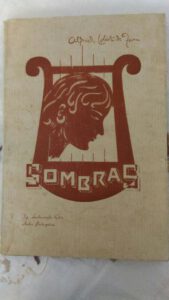

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

Looking back, looking forward

As the clocks ticks away, I can't help looking back on the year that was: a year full of ups and downs and challenges at every nook and corner. That an infinitesimal virus could hold the world hostage goes on to show how helplessly small proud humans truly are in the order of the universe. We are invited to appreciate the mystery of life and to realise that God is the overarching reality.

Here we are, on the threshold of 2021! There is a lot to be thankful for and a lot to be hopeful about. As we look back on 2020 and forward to 2021, St Paul helps put things in perspective: "We know that God causes all things to work together for good to those who love God." (Rom 8:28)

That's so very true. When we love God all things begin to fall in place, all things begin to make sense.

Happy New Year to all my esteemed readers!

Porque não vem a morte…

Um conto de Damodar Mauzó

Um conto de Damodar Mauzó

Traduzido do concani por Óscar de Noronha

É meio-dia. O sol, qual inimigo implacável, agride brutalmente a pele. O chão cá abaixo, o céu lá acima, e ardem as criaturas como as brasas do fogão a lenha! De todo o lado, um calor de escaldar.

Já lá foi o mês de maio, e o de junho está quase no fim, porém, não há sinal da monção. O solo quente, seco e mirrado de sede, olha súplice para o céu. Não há uma só nuvem no firmamento. Volve então os olhos queixosos, mas ai, não era capaz de verter uma só lágrima.

As mangueiras, as jaqueiras, as árvores de gralha e as palmeiras – murcharam todas elas, coitadas. Queimaram-se as folhas; as sobreviventes estão crestadas. E as arvoretas! Ora bem, vivem porque não lhes veio a morte…. Se é esse o estado das árvores, nem queira saber o que é da erva e do arbusto! Há muito que a erva se desenraizou, e ora lá se vê só areia. E os arbustos? Encontram-se no seu lugar umas esguias estacas.

As várzeas confundem-se com as hortas. Os poços secaram um por um; e as lagoas ressecaram. Até a sua lama se transformou em pedregulho. Os seres humanos da região safaram-se para terras longínquas. Os pássaros migraram para outros países. Pereceu o gado. Tudo que sobrevive espera a morte.

Nesse sol abrasador do meio-dia, passa por lá uma cobra-d’água levando consigo o seu rebento. Vai em ritmo acelerado. Faria algum sentido sair a essa hora? De mais a mais, é cobra, cuja natureza é de se arrastar pelo chão. Devia-lhe arder o corpo; pelos vistos, a cobra-d’água não se dá conta disso. Vai andando, com os olhos postos no filho. Quem visse essa cena não deixaria de lhe chamar louca. Mas... quem vai reparar nisso?

A cobra-d’água atravessa várzeas, hortas e valados. Deparando com um coqueiro, à sua sombra faz uma breve pausa; suspira e põe-se de novo a caminhar com o filhote. Ela própria não deve saber para onde vai.

A certa altura, encontra uma várzea. Ó minha mãe! Que tamanha que ela é! Mas evitando pensar nisso e de se deter na soleira, desce do valado e percorre os cômoros da várzea. Ó senhora minha! Quem a visse agora, não deixava de lhe dizer com dó: "Cobra-d’água, por que andas à soalheira do meio-dia? Contas pelo menos chegar ao outro lado? Cuidado com a tua vida! Melhor era voltares atrás para este valado. Fica ao pé desta árvore-de-gralha até à tardinha!…" Mas a cobra-d’água não se dispunha a ouvir. Nem tomaria a peito esse conselho. Quando muito, diria de passagem: "Olha, não há tempo para descansar! E que importa que eu morra no caminho? Ora, só porque a morte não vem..."

Essa várzea tem até os cômoros já desmoronados. Só se faz sentir a areia, essa areia quente! Lembra-se de quando, à cata de um rato, entrara na casa do José, vendedor de grão assado. Ficara num canto a observá-lo. O José havia deixado ao lume uma grande panela de barro, em que metera areia. Sobre esta, depois de bem aquecida, vazara grão, e ora... ao caminhar, arrepiou-lhe o corpo de se imaginar ela própria o grão sobre a areia!

‘Ai-ai!’ suspirou a cobra-d’água ao ver um valado que, à borda, tinha um anacárdio – árvore de bibó! Ansiando por um pouco de sombra, acelerou o passo e chegou-se ali. Subiu com algum esforço e meteu-se debaixo da árvore. Ó senhor! Onde está o seu filho? Até há pouco estava com ela. Aflita, voa pelo trecho do valado, quando afinal estava mesmo lá em baixo. Julgando que tinha dificuldade em subir, a cobra-d’água saltou, para prestar ajuda. Caramba! Porque está assim inerte? Ela só dá com o caso quando lhe toca com a cara….

Com a morte na alma, subiu de novo ao valado. Não tinha o mínimo de forças para levantar o corpo do filho. Sentou-se debaixo da árvore, a pensar. Passaram-lhe então pela mente um incidente após o outro.

Quando vivia o marido, não faltava nada à cobra-d’água; satisfazia-lhe todas as necessidades. E como adorava ele os filhos! Mas… não era essa a vontade divina. Um dia, o marido teve de sair à busca de alimento. Como tivesse muita sede entrou numa pia anexa a uma casa, à procura de água. Estava lá um caldeirão. Ó que sede de água! Desejando satisfazê-la, meteu a cabeça nessa panela. Entretanto, um malvado quebrou-lhe a coluna vertebral com uma paulada nas costas. Mesmo assim, a cobra-d’água, às escondidas, arrastou-se até à casa. Tentaram de tudo para a salvar, mas...

Ora, a cobra-d’água sentia vontade de morrer... Que tinha mais a fazer na vida? Mas não podia ser! O marido, à beira da morte, havia-lhe aconselhado a tomar conta dos filhos. Por isso, viveria só por amor aos dois. Porém, foi cruel o destino! Ambos –

Já o verão estava no fim, sem que houvesse o menor indício de chuva. Secos os poços e ressequidas as lagoas, nem para mezinha havia sequer uma gota de água. Nessas circunstâncias, a cobra-d’água superou todos obstáculos para cuidar dos filhos. Privou-se a si própria, mas não os filhos. Donde é que lhes arranjaria água dado que à própria terra escasseava? Entretanto, de sede morreu-lhe uma criança; e ficaram elas duas, a mãe e uma outra. Esvaziara-se toda a região. Haviam partido as serpentes, as cobras de rato e todas outras. Ficara só a pobre cobra-d’água, na expectativa de que viesse a chuva sem mais delongas. E só quando não podia mais, abandonou os seus bens, pegou no filho e partiu... E agora, este mesmo filho deixou-a!

A cobra-d’água derramou duas lágrimas.

‘Porquê choras, cobra-d’água querida?’ – de repente, ouviu ela uma voz, afectuosa, que lhe fez lembrar a do marido – e logo rolaram mais duas lágrimas.

‘Por amor de Deus, não chores assim!'

A cobra-d’água, cismada, lançou um olhar ao redor. Não estava ninguém no valado; além da árvore de bibó, nem uma planta sequer. Então, seria mesmo o bibó–?

‘Sim, sou eu mesmo, o bibó, que te estou a falar. Porque choras?’

Fitando a árvore, com os olhos marejados de lágrimas, e a sentir-se já um tanto aliviada da dor, soltou um grande suspiro e contou-lhe a sua história. Comoveu-se muito o bibó! Mas que podia ele fazer? Suspirou e guardou uns momentos de silêncio. Perguntou-lhe então a cobra-d’água: 'Ó bibó, estás aqui só, não estás? Isso não te aborrece?’

‘Que remédio? Dantes, tinha a companhia das trepadeiras e dos arbustos, e ali na borda estava uma palmeirinha. Mas... mas hoje, estou cá sozinho, a contar os dias. Quando me lembro dessa palmeirinha, fico triste! Nem coco verde chegou a dar; entretanto, foi-se embora, coitada!’

‘Não leves a mal esta pergunta, bibó!... O que te faz viver?'

Dentro em pouco, respondeu o bibó: ‘A minha vida já não faz sentido. Sei muito bem que mais dia, menos dia, hei-de morrer. Estou vivo, cobra-d’água... estou vivo somente porque não vem a morte!...’

O bibó vive porque não lhe vem a morte! Também eu vivia porque não me vinha a morte? Não! Vivia mas era por causa dos meus filhos – e sim, quem tenho eu agora? Porquê viver?

‘Entendo. Ó cobra-d’água, já sei o que estás a pensar. Ouve bem! Existem muitas criaturas no mundo. Umas estão desapontadas; outras sentem-se livres por terem já cumprido os seus compromissos, os seus deveres. Estas não pensam na morte; vivem pacatamente, aguardando a sua hora… E tu não deves morrer! Ouve lá! Existe uma lagoa a umas sete ou oito léguas a leste daqui. É pequenina. Vai tu ficar nesse lugar. Ninguém conhece o sítio, e não me parece que chegue lá alguém! Vai lá viver. Pronto, tens de viver, pelo menos porque te não vem a morte.”

Levantou-se a cobra-d’água; olhou para o bibó e começou a lacrimar.

‘Cobra-d’água, queiras fazer-me um favor!’

‘Diz, bibó, diz! Estou às ordens. Queres que eu fique aqui mesmo?’

'Não, cobra-d’água. Se ficares aqui, não viverás. Tens de ir mesmo. Mas antes disso, faz-me este favor...’ disse o bibó, emocionado. ‘Há mais de um mês que não vejo nenhum ser vivo. Hoje vieste tu. Seria um favor se por uma última vez serpeasses, à vontade, sobre o meu corpo…'

A cobra-d’água subiu num instante. Chegou até ao topo, trepando-lhe o ombro e enrolando-se-lhe à mão. E desprezando a sua própria dor, brincou e dançou, antes de descer da árvore. O bibó ficou muito contente. Então, a cobra-d’água volveu um derradeiro olhar ao filho e uma comovente despedida ao bibó, e pôs-se em direcção a leste.

O mesmo impiedoso sol. Chega o final da tarde, mas a terra está quente na mesma. O grande astro, a caminho do ocaso. Chega a tardinha. Põe-se o sol e some-se. Os seus raios vermelhos espalham-se pelo chão. A terra, que sempre a esta hora se apresentava tal qual uma noiva, parece hoje muito enferma. A cobra-d’água volta a andar e sempre a lamentar esse triste estado ambiental. Passa o lusco fusco e vem a noite, e ainda a aurora. Entretanto, a cobra-d’água, sonolenta, não se atreve a repousar: que será dela se inesperadamente cair num sono profundo? Tinha de chegar quanto antes àquela lagoa…. Ó esperança, já algum dia esqueceste alguém?

Mais um meio-dia; e o mesmo calor ardente! A cobra-d’água segue o seu caminho, sem o mínimo de descanso. Passa o meio-dia e vem o crepúsculo… Que é isso? Como secaram assim as plantas! De todos os lados parecem elas uns postes desnudados, e ainda no meio delas, umas plantas viçosas! Espanta-se a cobra-d’água, mas não se deixa ficar por lá.

… Era esta a tal lagoa! Haviam sobrevivido as plantas, só por estarem à sua margem! Seja como for, a cobra-d’água chegou! E então, que límpida essa água! Fica a cobra d’água a admirá-la por uns momentos. Logo depois, saindo do seu transe, vai até à beira da água. E quando a ia tocar com a sua língua sequiosa, lembrou-se do marido. Morrera precisamente ao beber água!... E dos filhos – haviam deixado o mundo angustiados por falta de água para beber!... E morre o bibó por não haver água – anseia morrer, mas vive só porque lhe não vem a morte.

Escurece. Com passos suaves, vem a noite. A cobra-d’água avança. Mergulha-se na água; há dias que não a via! Bebe até dizer basta; dança, brinca, nada, cai de sono… e dorme.

Splash! Splash! Desperta a cobra-d’água, intrigada com esse som logo à aurora, e vê lá gente! Cheia de medo, afunda rapidamente a cabeça; e quando a retira, vê um jorro de água a encher um camião-tanque. Assusta-se! Em tempos, vira bombear a água duma várzea. Que raio de seres humanos! Só Deus sabe como descobriram essa lagoa! Irão levar esta água e dentro em pouco não haverá mais! E… e… depois –

Baixa o nível da água; reduz-se a metade; e logo resta lá muito pouca… E –

‘Ei! Vejam aí, uma cobra-d’água!' grita alguém.

‘Traz-me um pau!... Anda cá….'

A cobra-d’água cerra os olhos. Tem saudades do marido e sente-se feliz por saber que vai ter morte igual à dele. Tem saudades também dos filhos – foi bom terem partido antes dela! E aquele bibó! Deve estar ainda a aguardar a morte! Porque não vem a morte….

‘Ai!’

'Valente! Foi um golpe de mestre!

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 7, Nov-Dez 2020

Moronn Iena Mhunn...

Damodar Mauzo-hachi lhan kotha. Devanagarintlem Romi lipiantor korpi: Óscar de Noronha

Damodar Mauzo-hachi lhan kotha. Devanagarintlem Romi lipiantor korpi: Óscar de Noronha

Donpar zal’li. Vot samkem dusman zal’le bhaxen angache kuddke kaddtalem. Ponda zomin ani voir vell. Randnicher dovoril’lia dhondsavari soglle jiv hulpatale. Charui vatten rokhrokh.

Mai ken’na kobar zalo. Jun-ui sompot aila. Pavsachem nanv nam. Dhortori taplea. Udkak haphaplea. Tanen tanelea. Aaxen babddi mollbak dolle laita. Punn mollban ek kup legit dixtti podna. Roddkuri portota ti. Punn golloitli mhollear dollean ek olem dukh legit iena.

Ambe, ponnos, vodd, madd soglle babdde bhavun geleat. Panam zoddleat. Ani zancher asat tim korpun geleat. Ani zhaddam! Moronn iena mhunn jietat. Vhoddlea rukhamchi oxi ghot. Magir tonnanchi and zhompachi khobor kitem vicharta! Tonnan dhortorek ken’na sodil’li. Tea zagear fokot renv dixtti poddta. Ani zhompam? Tanchea zagear distat ubeo boddio.

Xetam ani mollam ekuch distat. Bhãio ekan’ek poddong poddleat. Tollim sukun geleant. Thõicho rebo legit sukun fator zala. Ganvant ravpi moniszat ganv soddun pois gelea. Sovnnim sogllim dusrea dexant geleant. Gorvim sogllim morun geleant. Jogun vattavn uril’lea jiv moronnachi vatt polloitat.

Ani oslea vellar, donparchea kaddar ek henvallem aplea pilak borobor ghevn khõi tori veta. Soddsoddit cholta tem! Oslea vellar ani cholpachi mannsuki asa? Tantun henvallem tem! Sogllem ang bhuiek ghasun cholop tachem. Ang samkem lasta astalem. Punn henvalleak tachi jannvik asa-xi disona. Tem pilak samballit fuddem sorot asa. Konnui polloit zalear taka pixant kaddle bogor ravcho na. Punn… asa konn taka polovpak thõi?

Xetantlean, molleantlean, banda voilean tem cholta. Modinch madd dislo mhonntokir tem savllent khinnbhor ravn huskare soddta ani pilak ghevn fuddem cholpak lagta. Khõi veta tem tachem takach khobor asona.

Veta veta taka ek xet lagta. Avoi mhojea! Kedem vhoddlem xet hem. Punn ievzupak vell na ani votant ubem ravpachi mannsuki na. Bandha voilem denvun tem atam merê voilean cholpak lagta. Avoi avoi! Taka pollovpak thõi konnui asto tor tachi kakllut korun sanglem bogor na ravto – ‘Henvallea, aslea donparchea koddar kiteak veta tum? Poltoddin pavxi tori mu-go? Jiv vochot tuzo. Fattim sor ani hea bandhar io. Sanz meren rav hea vodda kuxik!...’ Punn henvallem tem aikupak naxil’lem. Tem ullovnnem monaruch ghenvchem naxil’lem tem. Choddxem zalear vetam vetam sangtem – ‘Arê, baba, suseg ghevpak vell konnak asa? Ani veta veta melem mhunn porva konnak asa? Atam moronn iena mhunn….’

Hea xetacheo merôi-bi kosol’leat. Fokot renv lagta angak. Hun’hunit renv! Henvalleak iad zata – ek dis chonnekar Juze-lea ghorant undrachea pilak dhorpak mhunn gel’lem tem! Thõi tannem kuxik ravn polloil’lem Juzen ek vhodd matie budkulo ujear dovril’lo. Tantun renv ghal’li. Ti tapt’kir tannem tantunt chonnem votil’le ani magir… choltam choltam ang xirxirl’lem tachem. He hun’hunit renvent apunnui bi tea chonnea bhaxen –

Hush’sh’! Henvallem huskarlem. To polloi bandh. Bandha degeruch ek zhadd asa bibeachem. Savlli tori mellteli matxi. Henvallean chal soddsoddit keli ani tem bandhar pavlem. Nett korun voir choddlem. Rukha ponda gelem. Arê, pil khuim? Arechea! At’tam axil’lem. Akant ailo tacher. Dhanvlem tem bandhar savn. Polloit zalear sokoluch asa tem pil. Voir choddpak zaina zatlem oxem mhonnun henvallean sokol uddki marli. Ab’ba! Hem ozun oxem oggi kiteak poddlam? Angak thond thenkov’n polloi zalear –

Dukhi monan henvallem voir sorlem. Tea pilak ghevn voir choddpa itli legit xokt tachea angant naxil’li. Tea rukha ponda tem boslem. Ievjita ievjita taka ek ek gozal iad zavpak lagli.

Tea pilacho bapui astana henvalleak khãich unnem naxil’lem. Magta tem to haddun ditalo taka. Kitlo mog axil’lo tacho bhurgeancher! Punn… Devachean tem polleunk nozo zalem. Ek dis to khavpak sodunk mhunn bhair gel’lo. Thõi to tanen tanel’lo mhunn udok sodunk laglo. Eka ghora kuxik manneant ek bhann axil’lem. Tanel’lo jiv! Pottbhor udok pit’lom mhunn tannem tokli bandda bhitor ghali. Itlean eka duxtt monxan tache fattir boddi marli. Fatticho manddko moddlo tacho. Tosoch lip-lipot to ghora ailo. Khub upai kelo – punn…

Henvalleak dixil’lem atam apnnei morchem…. Kitem korchem asa jitem ravn? Punn na! Morta astana ghovan taka sangil’lem, hea bhurgeank bore bhaxen voir kadd. Hoi! Hea don bhurgeam khatir mhaka jitem ravunkuch zai. Punn noxibuch futtkem! Donui –

Gim somplo punn pavsuch na. Bhãio sukleo. Tollim attlim. Vokhdak legit udkacho themb na zalo. Oslea vellar torektora korun henvallean pilank poslim. Khasa apunn upaxim ravlem. Punn tankam pottak marli nat. Punn zhõi dhortorekuch udok mellna thõi ti tori khõichean ditli? Udok udok mhonnit ek pil gelem. Urlim dogam. Pil ani avoi. Sogllo ganv rito zalo. Sorop, divodd, soglle gele. Ul’lem tem henvallem. Babddem az na faleam pavs aile bhogor ravcho na mhunn axen ravil’lem. Punn samkench ranv nozo zalem toxem tem uttlem. Santtlim-pottli soglli udovn, pilak ghevn tem bhair sorlem…. Ani atam tem pilui bi taka soddun gel’lem.

Henvalleachea dollean don dukham gol’ lim.

‘Roddta kiteak go tum, henvallea!’ okosmat avaz ailo, maiest avaz. Henvalleak ugddas ailo – aplea ghovacho. Ani tachea dolleantlean anikui don dukham ghollim.

‘Oxem roddunaka pollov’ia!’

Henvallean ojapan polloilem. Bandhar tor konnuch na. Ek zhadd legit na. Fokot bibea zhadd soddlear. Bibea zhadd tor nhoi mu?

‘Hoi. Hanvuch to bibo uloitam. Tum roddta kiteak?’

Bhoril’lea dolleamnim henvallean tea rukhak polloilem. Tachem dukh ekdom lhov zal’le bhaxen taka dislem. Ek vhodd suskar soddun henvallean soglli gozal taka sangli. Bibo! Vaitt dislem taka aikun. Punn kortolo kitem? Suskaro soddun to oggich ravlo. Henvallean vicharlem: ‘Bibea, tum ektoch hanga asa? Tuka vaz iena?’

‘Kitem kortolom? Poili mhojea sangatak vali axil’leo. Zompam axil’lim. Te deger ek kovathoi axil’lo. Punn… punn az hanv hanga ekttoch asam. Dis meztam. Tea kovatheachi iad zali mhonnttokir vaitt dista mhaka. Azun bondde legit ievunk naxil’le taka. Gelo bhavddo!’

‘Vichartam mhunn ragar zanv naka, bibea. Tum jieta kiteak?’ henvallean vicharlem.

Kãi vell ogi ravn bibean zap dili, ‘Mhoje jinnent atam kãi orth na. Hanv boro zannam, faleam ek dis hanv mortolonch. Hanv jietam, henvallea, mhaka moronn iena mhunn jietam –‘

Bibo moronn iena mhunn jieta! Ani hanvui moronn iena mhunn jietalem? Na! Hanv jietalem mhojea bhurgeam pasot – punn atam mhozo konn asa? Hanv kiteak jievum?

‘Mhaka kolltta. Henvallea, tuje vichar mhaka kollttat. Mhojem aik. Hea sonvsarant zaite jiv asat. Khub zann nirxeleat. Zaite zann apnnalim kortubam, apnnalem kortovio korun meklle zaleat. Punn te mornnacho vichar korinat. Te ogi bosun jietat. Mornnachi vatt polloit. Tuvem morunk favna. Mhojem aik. Hangasan udentek sat att konsar ek tollem asa. Lhan’xench asa. Tum thõi vochun rav. Azun meren thõi konn pavunk na. Ani konnui pavotxem disona. Tum thõi rav. Chol, atam tunvem moronn iena mhunn tori jievunk zai.’

Henvallem uttlem. Bibeak polloun tache dolle bhorun aile.

‘Henvallea, mhojem ek kam’ korxit?’

‘Sang, bibea, tum sangta tem aikotam hanv. Sang, hanv hangach ravum?’

‘Na, henvallea, hanga ravlear tum jievchem na. Tuvem vochumkuch zai. Punn voch’chem fuddem mhojem ek kam kor…’ bibeacho avaz katortalo. ‘Mhoino zalo, mhoje sori konnuch jiv ievunk na. Az tum ailam. Upkar korun mhojea angar ekuch favt meklleponnan bhonv….’

Sor’sor korun henvallem voir choddlem. Tengxer pavlem. Khandar choddlem. Hatacher bhonvlem. Aplem dukh visrun tem khell’lem. Nachlem. Magir sokol denvlem. Bibo khuxalbhorit zalo. Ek favt aplea pilak dollebhor polloun ani bibeacho ontoskoronnpurvek nirop ghevn henvallem udentek thondd korun cholpak laglem.

Tench rokhrokhit vot. Sanjevell zait ailea punn bhuim titlich hun asa. Vell ostontek lokla. Korta korta sanjevell zata. Vot denvta. Na zata. Tambddim kirn’nam dhortorecher pattollttat. Sodam hea vellar voklevori dispi dhortori az hantunnar poddil’lea vaittkara bhaxen dista. Soimek ail’li hi avkalla polloit henvallem fuddem sorta. Tinsanz zata. Rat sorta, fantodd zata. Henvalleak jem ieta. Punn nhid kaddpachi mannsuki na. Nhidlear thõich sust nhid lagli zalear? Poilim tea tollea kodden pav’ia. Aast! Tinnem konnak soddlam?

Porot donpar! Porot rokhrokh! Mat legit suseg ghenastanam henvallem vatt cholta. Donpar sorta. Tillsanz zata ani… Arechea! Tim zhaddam oxim koxim zogleant? Charui vatten sukheo boddio koxim zhaddam ani modinch panchvea pananchim zhaddam koxim? Ojapan henvallem fuddem sorta.

… Hench tem tollem! Tollea degevoilim zhaddam him, mhunn togleant borim! Zanv! Pavlem nimannem kodden. Ab’ba! Ani udok tori kitlem nivoll! Kãi vell ojapbhorit zavn henvallem thõich ubem ravta. Magir ekdom’ zagear ievn fuddem sorta. Udka moreant ieta. Tanel’li jib udkak tenkovpak taka iad ieta ghorkarachi. To udok pietnach mel’lo! Bhurgeanchi – udkak vollvollun tanni sonvsar sodil’lo! Ani bibo udok nasun morta – morn’nachi vatt polloita, moronn iena mhunn jieta!

Kallok zata. Rat mond pavlamnim ieta. Henvallem fuddem sorta. Udkant veta. Kitlea disanim tem az udok polloita. Pottbhor pievn gheta. Nachta, khelltta, penvta. Ani dolle jemetat. Henvallem nhidta.

Gasgass! Gasgass! Fanteaparar ho avaz koslo mhunn tokli voir kaddun polloi zalear monxam dixtti poddtat. Bhievn henvallem tokli bhitor ghalta. Portun tokli voir kadd zalear udkacho ghogo vanvta ani tem udok eka truck-hacher ttank’ient poddta. Henvalleak sot’tt zata. Tannem adim polloil’lem xetant pump lavn udok uspitat tem! Padda poddum he monis zatichem. Khõichean tankam hi khobor kol’li Dev zanna! Atam hem udok te vhortole. Il’lem il’lem korun somptolem hem udok! Ani… ani… magir –

Udok denvta. Ordhem zata. Thoddem urta. Ani – ‘Arê, tem polloiat. Henvallem!’ konn tori add’dota.

‘Boddi hadd re ti!... Tum oso io…’

Henvallem dolle dhampta. Taka ugddas ieta – ghovacho. Ghovachench moronn apnnakui ietlem mhunn khinnbhor borem dista. Bhurgeancho ugddas ieta – borem zalem, poilim gelim tem! Ani to bibo! Azunui to moronnachi vatt pol’loit astolo! Moronn iena mhunn….

‘Ã…’

‘Xabass, dhopkeak uddoilem mure!’

(Poilem xap'la Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 7, Nov-Dez 2020)

“The Fado in Goa is going to be a revolution!”

You can listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUDFr-Lauqo

O.N.: Let’s begin our chat with an incident that occurred in November 2017, that is, two months ago. Sónia, you received the Ustaad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar (National Youth Award) from the Government of India, in the traditional music category, which included Mandó, Dulpod, Dekhnni, Konkani Tiatr music and even… the Fado!!!

S.S.: That’s true!!

O.N.: That’s a great achievement, for it was finally Sónia who made sure that the Fado entered the history of India, and it is now registered as part of the Indian traditional music category...

S.S.: … traditional music of Goa!

O.N.: Congratulations!!

S.S.: Thank you!!

O.N.: It is well known in Goa that you recently launched a very interesting project called ‘Fado de Goa’. Could you enlighten us on this?

S.S.: The project ‘Fado de Goa’ started in the beginning of 2017 and was a result of another project from the year 2016 called ‘Fado in the City’ – a series of 10 concerts, at various venues in Goa. The idea was to take the Fado to audiences that had never heard, never attended a concert of Fado. At the ‘Fado in the City’ concerts we’ve always had people that neither spoke nor had any family member that spoke Portuguese. And I think this was the winning point of ‘Fado in the City’. And from there appeared the second project, ‘Fado de Goa’…

O.N.: And thanks to this new project, ‘Fado in the City’ could well be rechristened ‘Fado in the City and Countryside’!!

S.S.: Absolutely! ‘Fado de Goa’ is a different project. These are not concerts but Fado classes. With sponsorship by the Taj Group of Hotels and Resorts we conduct Fado classes. What is interesting is that in Lisbon, which is the land of the Fado, there are no Fado classes, no Fado schools, no Fado teachers. There are Fado singers, obviously, because it is in their blood and soul, and the Fado is in the Lisbon air! But here in Goa, we need classes of Fado… especially the present generation needs it, for they don’t have the contact that Goa earlier had… That’s because Fado has existed in Goa since the 1800s. We have books that prove that the Fado was already here in the 19th century. Fado was born in Lisbon around the 1830s or 40s, and arrived in Goa as early as the 1890s, or maybe even earlier.

O.N.: But can we be sure that it was Goans who used to sing the Fado, or was it the Portuguese that lived here?

S.S.: The Goan people! Because the booklets that I have, which were printed and published here by Tipografia Rangel, in Bastora, have lyrics and notations of the Fado as well as the Mandó. So, it had to be for people that spoke Konkani.

O.N.: Yes. And just out of curiosity, what were the titles of these fados?

S.S.: There was one titled “O Órfão” (‘The Orphan’) and another, “Fado”.

O.N.: You mean, it had the lyrics as well as music notations…

S.S.: Yes, the lyrics and the music notations! They were booklets for music students to play and sing fado, mandó and other forms.

O.N.: Interesting!

S.S.: Yes, indeed! So we know that the fado has been living here for all this time. Thus, it is one of the forms of traditional music of Goa.

O.N.: And have these fados been performed in Goa? For example, how would it feel to sing “O Órfão” today?

S.S.: I don’t know if they could be performed in our time, as the language has also evolved. We are talking of a time span of 200 years back from now. Even in Portugal the spoken language is way different today. And in the fado, lyrics have evolved, the manner of writing the stanzas as well as performing the fado, has changed. So, while I’m not sure if those fados could be performed today, yes, an attempt could be made to modify those old lyrics. Maybe! Who knows!

O.N.: Right! One never knows how it will play out… Well, let’s talk now about the Fado classes. What fados are the students learning to sing?

S.S.: In the classes that we have had it was not only singing that was taught but also theory about the Fado, because there is a misconception in Goa that any song in Portuguese is a fado. Which is not so! So, we had to teach the rules of the fado, its history and origin, famous Fadistas – Maria Severa, Amália... of course – the instruments used in the Fado, the places where fado is sung live, areas of the Fado in Lisbon, like Alfama, Bairro Alto and Mouraria; the various categories of fado, what exactly is traditional fado, and such topics. So, it is theory as well as Fado singing that is taught…. We’ve already had four groups, the first being in Margão, the second in Panjim, the third in Vasco da Gama and the fourth again in Margão.

O.N.: So there has been interest...

S.S.: Yes! And now they’ve invited us to have a batch in Mapusa plus a second batch in Vasco da Gama.

O.N.: And what are the age groups?

S.S.: We’ve had batches of about 30 students and in Vasco we ended up having 60 students. From school children up to grandparents!! At times it was such a cute sight!... There were members of the same family, like parents and children, siblings, cousins; we even had a pair comprising a grandfather and his granddaughter… studying together for the final exams. Because there is an exam for all students, written as well as orals.

O.N.: What is the duration of the course?

S.S.: The course is of 10 weekly classes. But at times we had to postpone classes due to school exams or feasts; we’ve had breaks. So considering everything, I would say it takes about 15 weeks. At the end of this, a ceremony is held where the students are presented a certificate. There are no ranks or grades given; the certificates simply say that the student has completed the course held by Fado de Goa. Because in Lisbon itself, there are no formal courses of Fado, and we are no authority to grade...

O.N.: Who else is associated with the project? For sure, you have a team…

S.S.: Oh, for sure! Absolutely required. The main support comes from the Taj Group of Hotels, who under their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to protect a dying art form have chosen the Fado in Goa... Our team comprises Musician Carlos Manuel Meneses, who is present at all the classes, to accompany the students as they learn. We have an administrator in Marlene Meneses, who coordinates the groups, admissions, communication, etc. We have other musicians, like Orlando de Noronha and Dr Alan Abreu; and we have heads of Fundação Oriente (Goa), Instituto Camões; Spic Macay, which works to protect the classical music of India and are going to include the Fado in that list. So that’s our steering committee. We have meetings to decide and steer the project.

O.N.: So it is really a large-scale project...

S.S.: Yes, indeed! We hope to discover 100 fadistas in Goa!!

O.N.: Excellent! And for sure you hold the key to that…. Well, talking of the Fado, you must have musicians, too... What about training musicians?

S.S.: Yes, we do need to! From among the students of our four batches, after the exams, we’ve selected students to go to the next level. They are students with potential to sing and who we will train to become fadistas to sing on stage, not merely at parties… and that is where we require musicians. We hope to have a workshop – not finalised when! – of Guitarra Portuguesa (Portuguese Guitar) as well as Viola de Fado (Fado Guitar), for sometimes we can sing the fado without the Portuguese Guitar but we can’t do without the Fado Guitar! It is easy, because here in Goa we have so many extremely talented musicians who already play the classical guitar, and only need to learn the technique of accompanying the fado. That’s all.

O.N.: Very well! So, we wish you, Sónia, all the best in the project, which doesn’t look like a mere project but an adventure with the Fado!...

S.S.: A revolution!

O.N.: A revolution, indeed! We wish you all the best in this adventure and revolution!

Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 7 (Nov-Dec 2020)

Pangim da minha infância

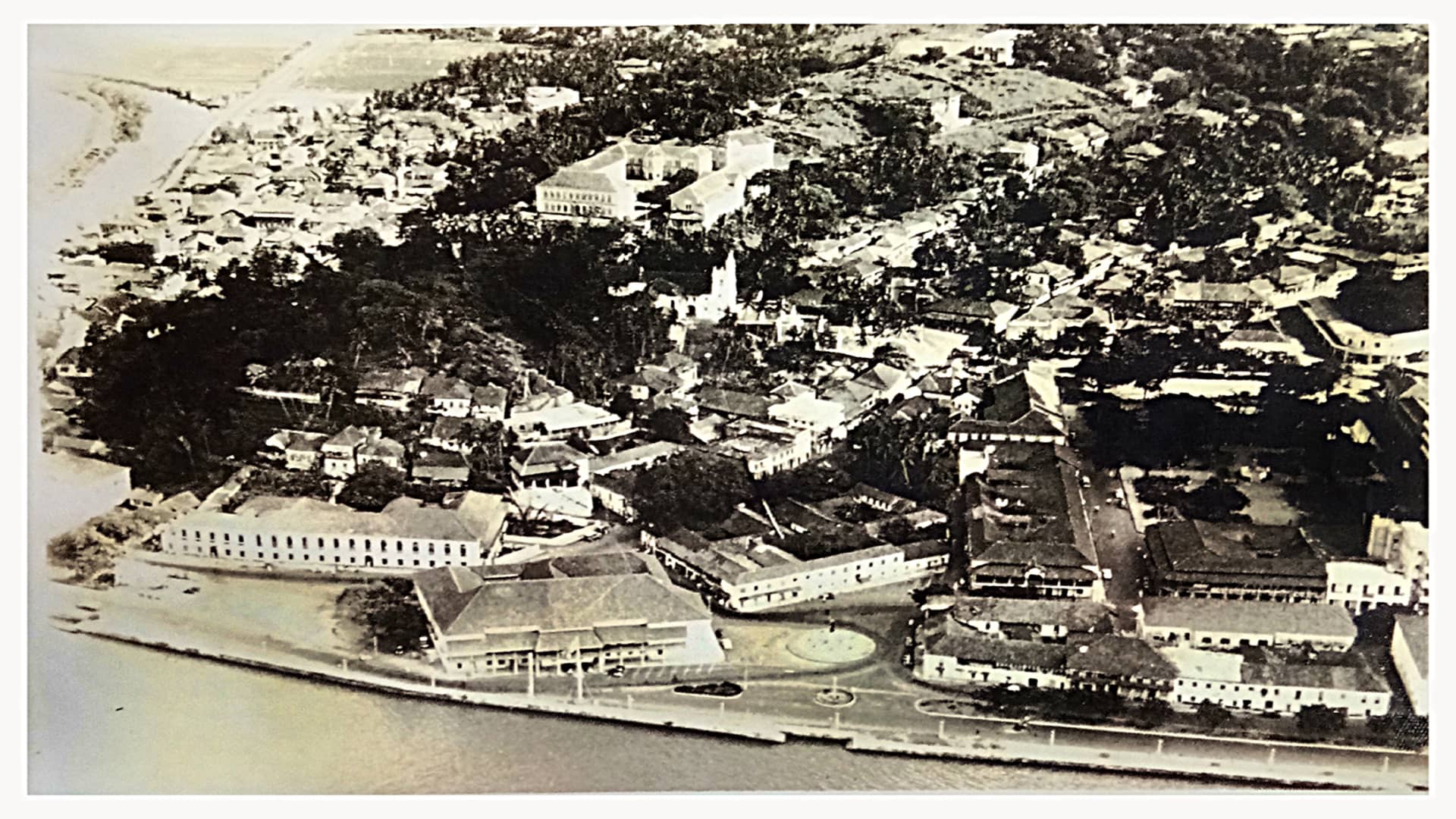

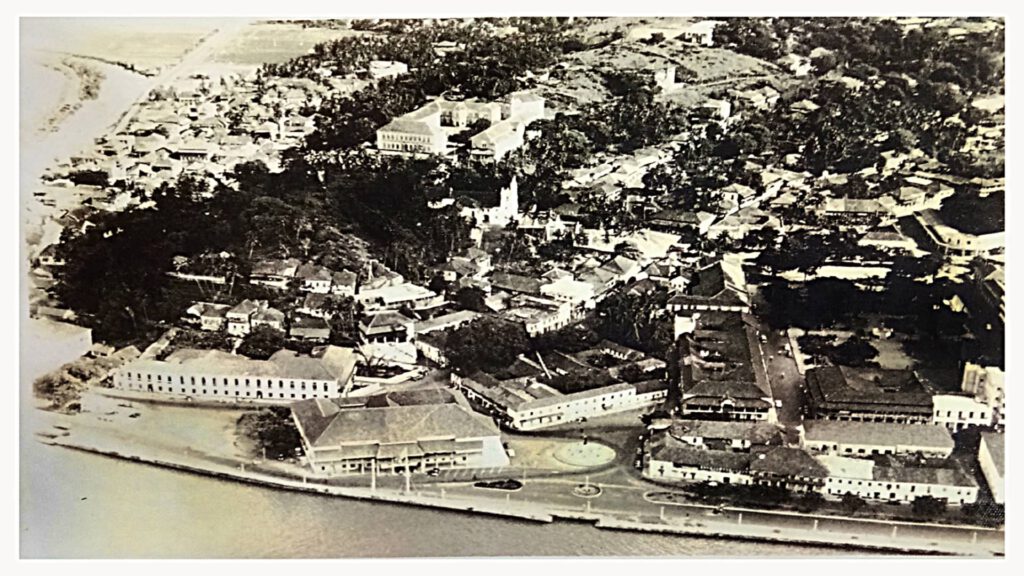

Nas décadas de 60 e 70 do século XX, a cidade de Pangim era a imagem da calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro. Estendia-se da Rua de Ourém ao Hospital Militar (na direcção leste-oeste) e da avenida marginal ao Altinho e Batulém (na linha norte-sul). Como jardim à beira-mar plantado, a quem o suave Mandovi pautava o ritmo da vida, Pangim tinha uma identidade própria e um encanto muito seu.

Vivia eu no coração de Pangim, ao pé do antigo Palácio do Idalcão e sob o olhar hipnótico do Abade Faria. Raiava o nosso dia com o chilrear dos pássaros, seguido da sonora sereia do barco de Bombaim a atracar no cais da Alfândega. A essa hora, o vaivém apressado da multidão, a algazarra dos bagageiros e a buzina dos táxis na Avenida Vasco da Gama (hoje D. B. Marg) eram um chamariz para uma boa parte dos 40.000 pangimnenses ainda envoltos em sono; um impulso matinal para as suas tarefas, sobretudo a escolar.

Era como se o frenesi da metrópole indiana tivesse acabado de desembarcar na capital goesa! Essa onda pressurosa propagava-se um pouco por toda a parte, a começar pela Avenida Dom João de Castro e a Rua Afonso de Albuquerque (ora M. G. Road), as principais artérias, dominadas pela burocracia e pelo comércio. Com a partida daquele barco, no meio da manhã, a cidade voltava à calmaria; almoçava e dormia a sesta, e pelas 4,00 horas retomava a batalha quotidiana que só terminava por volta das 8,00 da noite.

Uma vivência orgânica, não muito diferente da do campo! À devida hora vinha à porta o pão e o peixe fresco; iam às compras os empregados domésticos, que se prezavam de ser íntegros, temendo não tanto a polícia como a Deus! O trânsito era ligeiro – motocicletas, bicicletas, até carroças, e automóveis, do popular Volkswagen ao luxuoso Cadillac. Estes eram os últimos abencerragens da bonança que resultara, paradoxalmente, do Bloqueio Económico de 1955, e ora simbolizavam o nosso cosmopolitismo.

Disse um escritor japonês que Pangim era a “most unIndian of all Indian cities.” Referia-se certamente à tradicional arquitectura indo-portuguesa, desprovida de arranha-céus e da imundície e do caos que caracterizavam os centros urbanos do subcontinente. Mas teria ele dado conta da arquitectura espiritual do povo? Este não era de grandes ambições e vivia numa mediania. O roubo era raro, e raríssimo o homicídio ou o suicídio. Não havia indícios de sectarismo ou de violência, pois reinava a consciência e a benevolência, ou aquilo a que chamamos munisponn: se à porta humildemente batesse alguém, sentava-se à mesa com a gente – como canta o fado; e no conforto pobrezinho do lar havia fartura de carinho, e bastava pouco para alegrar a existência do citadino.

Pois é, a cidadezinha daquela época tinha um só diário em português (O Heraldo) e em inglês (The Navhind Times); uma só emissora (a All India Radio); um só salão (o do Instituto Menezes Bragança), onde actuava a única academia de música; um único hotel de categoria (o histórico Mandovi); uma só loja de gelados (o Esquimó); um só restaurante sul-indiano (o Shanbhag); um único hospital geral (o da Escola Médica); um único cine-teatro (o Nacional); uma só livraria (a Singbal); uma única biblioteca de fôlego (a Central); uma só grande praça pública (o Azad Maidan); um só campo de jogos público (no Campal); um só amplo jardim (o Garcia de Orta), onde, à tarde, convergiam crianças e adultos, ficando aqueles a saltitar pelos canteiros e estes a conversar amenamente num canto.

Desse jardim guardo várias memórias: a da música executada no seu artístico coreto e a dos slogans – “Tujem mot konnank? – Don panank!” – que eu ingenuamente gritava, nas vésperas do Opinion Poll, em 1967. Lembro-me dos cafés e bares em redor e do jornal em cuja Redacção se ouvia um aflitivo dize-tu-direi-eu, nem por isso resolvendo os problemas da carestia e escassez, da pobreza e embriaguez, estas comuns, por sinal, no bairro pitorescamente denominado Tambddi Mati (Terra Vermelha), tanto por falta de asfalto nas ruelas como pelas lampadazinhas vermelhas nos alpendres!

Enfim, Pangim não era nenhum jardim de virtudes. Até pensara em mudar de cidade, por não suportar a insularidade e me sentir everybody’s business; mas em vez disso mudei de ideia, por recear que entretanto a cidade da minha infância se transformasse num pequeno Bombaim, e nós, em nobody’s business! Mas não havia remédio; a cidade estava já em franca expansão: as casas cediam o lugar a blocos de apartamentos; era construída uma ponte sobre o Mandovi e uma praça de automóveis no pântano do Pattó. Por outro lado, estava incompleta a rede de esgotos; havia falhas na electricidade, e era racionada a água canalizada. O ar era puro; mas ai que, na monção, Pangim de repente era Veneza!...

Ora, fui aprendendo a amar a cidade e a gente. Éramos poucos, éramos irmãos – e saudáveis as relações entre os vizinhos, independentemente dos seus credos. Naqueles tempos, os cavalheiros tiravam o chapéu às senhoras e paravam para dois dedos de conversa! Os baptizados, aniversários e funerais eram eventos de vulto. Não havia televisão; para dissolver o tédio bastava um passeio pela praia do Miramar ou de goddia-gaddi até ao Campal, ao pôr-do-sol. O arraial nas Fontaínhas, o desfile do Carnaval e os bailes nos clubes Nacional e Vasco da Gama vinham a seu tempo. Dir-se-ia o mesmo da Via Sacra; da procissão das velas que do Paço Patriarcal descia até ao ex-libris da igreja matriz; e das novenas e festas religiosas. De tudo isso nascia o espírito de família e a alegria de viver em Pangim.

No afrouxar forçado dos meses da covid-19, voltei a descobrir o rosto da minha cidade. Se em tempos nos faltavam coisas que os outros tinham em abundância, hoje, sentindo novamente aquela calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro, vejo que nos não faltara nada…. Não admira, pois, que Pangim tivesse sido sempre a menina dos olhos de todos os que se prezavam de ser goeses!

Foto de Pangim, gentilmente cedida por Willy Goes

Publicado na secção portuguesa do magazine dominical do diário Herald

Our ancestors respected nature and lived in harmony with it!

“Our ancestors were more sensible. They respected nature and lived in harmony with it,” says Scientist António Mascarenhas, formerly of National Institute of Oceanography, Goa, while assessing the state of the Goan environment, in an interview with Óscar de Noronha.

For original interview in Portuguese

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BvDOm45GCQ&t=759s

O.N. – What are the issues afflicting Goa's natural environment at this time?

A.M. – There are several issues, right from our forest heritage to more serious ones, such as the improper exploitation of our mining resources, the levelling of khazans (wetlands) to build housing complexes; the contamination of our rivers – and now also the attempt to nationalize them, and so on. But to me, the conservation of the dune-beach ecosystems is the most serious issue that exists.

O.N. – What’s the reason for that?

A.M. – Well, any human action on the landscape results in two types of impacts: reversible or irreversible. Now, the disappearance of the frontal dunes causes the beach to recede, making the coastline much more vulnerable to the action of the sea.

O.N. – So, in order to properly address the environmental status of our territory, we must qualify these matters, mustn’t we?

A.M. – For sure! Google Earth shows where Goa stands! Let’s, then, do a fly-by, say from our beaches to the Western Ghats, across the khazans that are our rice paddy fields. We will see the kind of impact that the different areas of the territory have suffered. For example, if a forest is destroyed, the system can be rejuvenated; and a contaminated river can be oxygenated; even khazans converted into a housing area is recoverable. But the destruction of the coast is almost always irreversible.

O.N. – What examples do you have of this in Goa?

A.M. – Well, in Sinquerim and Candolim, the beach retreated due the impact of the River Princess ship that was stuck there for twelve long years! The dunes were flattened also to make place for hotels and residences. The fact is that the dunes do not get replenished easily; sometimes the sand takes decades to come back. Of course, to speed up the process, the beach can be nourished, by filling up the affected parts with new sand. This process also occurs naturally during the period after the monsoon, between September and March. For example, in Baga, Morjim and Querim, a sandy tip is formed. The tip is caused by the sand transported by the coastal current that enters the river or estuary, and is then pushed counterclockwise by the sea. Further north, the dunes disappeared to make way for shacks, with the exception of Mandrem, Morjim and Galgibaga…

O.N. – The case of Galgibaga, in the taluka of Canacona, is different, isn't it?

A.M. – Yes. This area is protected by the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) law, and is considered a breeding ground for turtles, one of the four sites in Goa. Hence, urban development in this place is completely forbidden. And thus the beach has remained well preserved. But on those dunes, there are small little houses that function as restaurants. The National Green Tribunal has ordered their demolition.

O.N. – As far as I know, the dune protection in Miramar was one of the first environmental campaigns that you undertook, in 2007, well over a decade ago...

A.M. – That's right. I was part of the Goa Coastal Zone Management Authority, and am at present a member of the Goa Biodiversity Board. One of the projects we proposed was to save these frontal dunes. Some sites have been indicated where you can replicate that experience of dune reconstruction. Miramar beach is already being considered for this.

And talking of Miramar: here you find a semi-circular sand deposit, in the form of a sand bar, perhaps one of the few its kind in the world. It accretes and gets washed out, and then the sand comes back during the monsoon. It is an annual phenomenon and has been going on for centuries. The feast of the church of St. Lawrence, on the Sinquerim hilltop, from where you can see the silting, coincides with the opening of the sand bar…. I don’t know the connection.

O.N. – That was one reason why Albuquerque had to wait until the end of the monsoon to win Goa back... Here we see a connection between a natural phenomenon and a historical occurrence….!

A.M. – That's right. There is that 'tongue of sand’ at the site, now known as the Aguada sandbar. Here the navigation channel is very narrow and, after the monsoon, it opens up naturally. Unfortunately, the authorities are thinking of dredging the channel, and that’s going to be a real tragedy. Scientist C. S. Murthy has described the functioning of this area. The currents go south to north while on the other side they flow from north to south. On the coast, the currents run from south to north, from Caranzalem to Miramar; and from north to south, from Campal to Miramar. This process is responsible for the formation of the tongue of sand in Miramar. During the monsoon, when the waves caused by the winds from the west reach Miramar, they cause sand erosion; and later, when the good weather returns, the currents get normalized, helping to rejuvenate the beach. This has been an annual process noticed for decades.

O.N. – And does that protect the coast?

A.M. – Well, it was wrongly assumed that the coast would be protected with the construction of a barrier or wall made of large basalt stones brought perhaps from Maharashtra. But this wall has caused the beach to disappear and today we only have those stones left there. This human action on the beach has had consequences just in front of the old Medical School. The Campal stream flows out here. At this point a sandbar has emerged, blocking the passage of the said stream.

O.N. – By and large, is the ecology of the capital city at risk?

A.M. – The danger is not of very great proportions but it is also not something that can be ignored. For example, saline water enters and flows up to where the Fire Brigade is currently located. Despite this, there are many who have an interest in reducing the status of the stream to that of a nullah, a mere drain. The geological maps of the Survey of India of 1965 prove that there is movement of the tidal waters. Therefore, the stream is comes under the purview of special laws relating to the preservation of coastal zones. On the other hand, if it is reduced to the status of nullah, the said area will be outside the scope of those laws.

O.N. – There was destruction of the dunes when the area of Caranzalém was urbanized... What irreversible effects are we witnessing today?

A.M. – Well, in the 1990s the Caranzalém swamps began to disappear, which today are the largest urban area located in the wetlands in Goa. Before this, in the 1970s, the largest area that suffered destruction was where the bus terminus of the capital is located. Today, the high-rise buildings there have their foundations as though floating in the groundwater. These waters are now contaminated. All the wells in the city suburbs have no potable water – whereas I have a fresh-water well at my house in the village of Raia.

O.N. – And for that matter, what is your say on the Mandovi, which is the hope of salvation not only for the capital but also for the territory?

A.M. – It so happens that the neighbouring state Karnataka, where the Mandovi is born, has been trying to divert the water at the very source. The case is in court. Meanwhile, today, Mandovi's condition is nowhere near the same as that of Delhi's Yamuna or Bangalore's Ulsoor Lake. It is less oxygenated but, fortunately, not only does the monsoon refresh the river but also its connection to the sea neutralizes all harmful influences.

O.N. – You have been a scientist at the National Institute of Oceanography... What is the relationship between oceanography and the ecology of the hinterland?

A.M. – Let me explain: The oceans are controlled by the tides twice a day. The water levels rise and fall. The same happens in rivers. In Goa, the impact of the sea is felt up to the remote village of Savoi Verem, in the taluka of Ponda, and up to the village of Macazana of the taluka of Salcete there is appreciable amplitude of tides and saline influx. So, the ocean is connected with the smallest stream. This is confirmed by mangroves, which indicate the presence of saline water. In fact, the area that goes from Cortalim to Macazana, passing through Curtorim and Rachol, has large mangrove swamps. The same can be said of the area between Carambolim and Agaçaim, passing through Azossim, Mandur and Neura.

O.N. – Which is the regulatory authority for wetlands?

A.M. – Well, it is interesting to note that all khazans belong to our Comunidades (agricultural communities). But presently the recently formed Wetland Authority of Goa is in charge. The khazans function as reserves of drinking water. Hence it is essential that our Comunidades are aware of the issues and assert themselves.

O.N. – It seems that the mangroves have helped to afforest the territory…

A.M. – That's right. But this too has to be controlled because mangroves are "colonizers". For example, in Panjim, a mangrove has appeared in an area that was traditionally a salt pan. Likewise, the floodplains at lower levels are now invaded by these trees; and this prevents farmers from cultivating the fields.... These mangroves have engulfed the Linhares Bridge from Panjim to Ribandar and are thus destroying the identity of the historic bridge. And to complicate matters further, there is a garbage treatment plant in the middle of the same mangrove lagoon. These are matters that call for attention.

O.N. – You are a recipient of the ‘Green Heroes’ award from TERI (Tata Energy and Resources Institute), New Delhi. You write regularly for the newspapers, popularizing many of the subjects we’ve talked about today… Is the level of public participation in these matters something that satisfies you?

A.M. – I’m neither satisfied nor frustrated. For 36 years I worked at the National Institute of Oceanography in Goa, a public funded organization. Salaries are paid by the Public Exchequer; hence my primary duty is to meet the needs of society in general and, in particular, to contribute to the conservation of nature.

Of course, public participation in these matters could have and should have been better.... We have the obligation to know the functioning of natural ecosystems: the functioning of the coast and the hills that are found in the hinterland. But it seems that today we suffer from information overload. There are many who do not read, there are others who read but do nothing, and only a few who do act proactively.

But the important thing is that to have proper planning and coordination between the authorities. To manage these issues, a cross-sectoral approach is indispensable. And there should be no politicking. The whole matter must be treated as a sacred cow: the mangroves, dunes, marshes, tidal areas, beaches are all sacred. They are exclusively under the responsibility of Coastal Regulation Zone I (CRZ I), but there have been deviations, there have been transgressions…

O.N. – You’ve travelled through Europe. What initiatives have you noticed?

A.M. – For example, in 2007, I visited the University of Algarve, as a fellow of Fundação Oriente. The sand dune systems there have been recreated. On the beach of Tavira, in a part of the marsh called Ria Formosa, there are now long dune areas; these have been artificially reconstituted but work naturally. Some wooden bridges have also been built that help visitors move to the beach without trampling the frontal dune. Faro beach is a good example of conservation of the fore dunes.

We have similar examples In France. The beach nourishment technique is employed for sand restoration purposes, and this controls erosion. Also erection of wooden fences blocks wind borne sand; and over time these sandy deposits become the frontal dunes.

That's precisely what we propose for Miramar Beach. Well, it also helps to have plantations on the dunes: they help stabilize the dunes.

O.N. – It is obvious that much depends on the political will and public participation in safeguarding our heritage...

A.M. – Yes, there’s no doubt about that. I would be happy if the authorities and the general public were convinced of the great importance of the conservation of natural systems, in particular the coastal area, our beaches and the dunes. These are the first line of defence against the incursions of the sea. If we save the dunes, the population will be saved in the event of an attack from the sea. The tsunami of the year 2004, which devastated parts of Tamil Nadu, has already proven this theory right. I always say that the population was decimated not by the tsunami but by our recklessness in provoking the forces of nature, with construction of urban structures in inappropriate places. In this respect, our ancestors were more sensible. They respected nature and lived hand in hand with it. Thus, from Canacona to Pernem, they were always safe and sound.

O.N. – Well, it was a pleasure talking to you. Thank you for the panoramic view that you gave us on a topic of great importance to our beloved Goa. Thank you.

A.M. – Thank you! Thank you very much!

(First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, II Serie, N.º 6, Set.º-Out.º de 2020)

https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:80665fef-61a8-44bb-988a-e697ace84c22

As realidades da nossa identidade

As minhas primeiras palavras são de agradecimento pelo honroso convite que me foi feito de integrar o conselho editorial desta dinâmica Revista, e de saudações aos leitores. Aceitei-o de bom grado por se tratar de um elenco de obreiros culturais com quem doravante poderei colaborar mais estreitamente. E, pela obra feita, os meus parabéns e votos de longa vida à Casa e à sua Direcção.

Para além desses laços que me unem à Revista da Casa de Goa, é a própria terra e cultura de Goa que me acenam. Vivo no meu torrão natal, porém, não pretendo conhecê-lo melhor do que outros que não têm esse ensejo. E nem se pode dizer que os que se ausentam por força das circunstâncias têm menos amor à terra dos seus antepassados. No nosso caso, o que vale é ter o coração sempre a bater por Goa.

Mais. Não é somente o sangue que determina a cidadania cultural. Goa, que conheceu outros povos e culturas, poderia comprovar que no decurso da sua longa história foram muitos que se apaixonaram por ela. Ainda hoje, há pessoas que têm um enternecedor amor, dir-se-ia mesmo uma ligação espiritual com ela. A nós cumpre enaltecer e perpetuar o que há de nobre nesse talismã que se chama Goa.

Podemos dizer, sem receio de errar, que Goa é ao mesmo tempo terra e estado de espírito. E quem somos nós? Na feliz frase de António Colaço, “somos uma pequena e grande família. Não há aqui hindus, moiros ou cristãos. Há só Goeses”. Importa salvaguardar a nossa irmandade, deixando-a viva tanto em Goa como em Lisboa, enfim, em todos os lugares onde se encontram os Goeses, desde os tradicionais kulls ou clubes nas metrópoles indianas até às associações culturais e desportivas dos goeses espalhados pelo mundo.

Neste particular, devem Goa e Lisboa assumir um papel de liderança. Essa liderança se impõe pelo facto de serem elas os pilares da universal Casa e Espírito de Goa. Graças a Lisboa, a minúscula Goa foi em tempos o ponto de encontro do Oriente e Ocidente: aí se fundiram as culturas lusa e indiana; aí dois mundos se trocaram; aí se deu aquilo que Gilberto Freyre designou de “milagre sociológico”. Goa e Lisboa foram mesmo precursores da globalização.

Fica assim bem clara a acção pioneira que tiveram Goa e Lisboa no conhecimento mútuo das sociedades e culturas. Em ambas as cidades o elemento local se tornou universal, e vice-versa. Como agentes de transformação dos povos que mal se conheciam; como modelos de paz e amor fraterno, Goa e Lisboa têm os seus nomes escritos em letras douradas. Só que jamais se pode falar de amchém bhangarachém Goem – “nossa Goa dourada” – nem Lisboa se pode gabar de capital cultural sem problemas.

Nessas voltas que o mundo dá, festejemos a nossa identidade, cantando os louvores à língua e literatura, música e arquitectura, indumentária e culinária, às nossas seculares instituições e tradições, mas reconheçamos também as novas realidades…. Aquilo a que chamamos Goa, existe ela na realidade, ou é uma simple miragem? Se existe, até quando será ela goesa? E esse espírito, estaria ele claro ou cada vez mais nebuloso?

Nesse sentido, urge uma conscientização e relevante acção. Consistiria em viver com amor ao torrão natal; valorizar o seu património; salvar o meio ambiente; cultivar as terras com engenho e alegria; e acima de tudo, participar activa e patrioticamente na governação, com plena consciência dos valores subjacentes à cultura goesa.

Nesta Revista e noutros lugares, enquanto delineamos o nosso ideal, trabalhemos com os corações unidos em volta desta louvável causa comum.

(Editorial na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Serie, N.º 6, Set.º-Out.º de 2020)

https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:80665fef-61a8-44bb-988a-e697ace84c22