Mario is Forever

When contacted by Dolcy D'Cruz of Goa's leading English-language daily Herald, for comments on the public screening of the documentary "The World of Mario... Seriously Funny!", https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Fj-KEN2kQI , researched and scripted by me for Doordarshan Goa, here is what I said, in reply to the journalist's questions:

On challenges faced

Mario had the world for his canvas, so the main challenge was to be able to truly cover his creative life in a short documentary.

Identifying the right talking heads and liaising with them was another challenge. His sister Fatima gave us valuable inputs. And we also got on board film-maker Shyam Benegal, Indian adman Gerson da Cunha, architect Gerard da Cunha who owns the Mario Gallery, and many others.

https://epaper.heraldgoa.in/oHeraldo?eid=1&edate=22/10/2024&pgid=52727&device=desktop&view=2

On his relevance

Mario is a curious case of a self-trained artist who had different styles, worked with different mediums, and across the print and electronic media.

It is a civic duty to pay homage to the greats of our land. Mario loved Goa and worked towards preserving our culture and heritage. Many tourists used to come here in the hope of finding ‘Mario’s Goa’ but often they were disappointed on seeing that Goa had changed a lot.

On a personal note

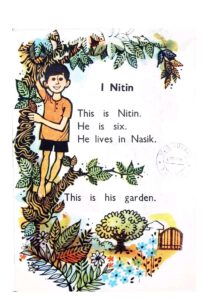

Working on Mario took me back to my Bal Bharati textbook. As kids, few must have known that the illustrations were done by a great Goan artist.  Then, I saw him and his dog in the pages of the Illustrated Weekly. Finally, I met Mario face to face for the first time in 1987, at the Gulbenkian in Lisbon. On his exhibition catalogue he scribbled, ‘For Oscar, Saudades, Mario’, and suddenly I felt I’d known him forever.

Then, I saw him and his dog in the pages of the Illustrated Weekly. Finally, I met Mario face to face for the first time in 1987, at the Gulbenkian in Lisbon. On his exhibition catalogue he scribbled, ‘For Oscar, Saudades, Mario’, and suddenly I felt I’d known him forever.

Also, he very kindly illustrated my dad Fernando de Noronha’s memoirs, Momentos do meu Passado, which he said had brought back nostalgic memories of his youth in Goa.

To me, those saudades remain – of a gentleman with a twinkle in his eye, an unassuming genius, a lovable character, just like all those that he has immortalized in his illustrations and cartoons.

-o-o-o-o-

Here are a few pictures of the event, which comprised the first public screening of the "Stories and Documentaries" series at DD Goa auditorium, inauguration of the digital screen and felicitation of the documentary team, and superannuation farewell of a DD Goa veteran:

Governor of Goa addressing the audience

Governor of Goa addressing the audience

Pics, courtesy: Bambino Dias, Thomas Rodrigues Lorraine de Noronha, Miguel Furtado and Emmanuel de Noronha

Passion and Glory

‘The greatness and the power and the glory and the majesty and the splendour’ that the Book of Chronicles (29: 11) speaks of as belonging to the Lord belong to us humans as well. The difference is that in God’s hands those values are transformative; in human hands, they turn ordinary and dull, and often degenerative.

Today’s Readings speak of the purpose of those values and how to avoid the most obvious pitfalls. The First Reading (Is 53: 10-11) is taken from the Fourth Song of the Servant, which begins thus: ‘Behold, my servant shall prosper; he shall be exalted and lifted up, and shall be very high.’ While this is sure to give every human a high, in the verses that follow, which make up today’s Reading, we see that glory comes with a price – also very high.

Isaiah’s Suffering Servant prefigured Jesus Christ. His Song indicated that He would be despised, rejected, esteemed not, afflicted, wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities, oppressed, stricken… And if this is not a description of Our Lord’s Passion, what is? He redeemed us through His Passion and Death. The Jews, too, traditionally believed that the Suffering Servant referred to the Messiah or Redeemer who was to come to Zion. But, irony of ironies, they rejected Him when He actually came!

Hence, in the Gospel (Mk 10: 35-45), Our Lord makes it amply clear that the Son of Man came to give His life as a ransom. He did not come to enjoy earthly glory but rather to suffer for the sins of humankind and raise it to a glory that is eternal. Here, two of His close disciples – James and John, sons of Zebedee – were hideously off the mark. They sought the highest ministerial berths from Him who they thought had come to rule over Israel! Our Lord obliged the Good Thief instead, who was crucified to His right hand….

However, handling the disciples’ feelings of self-importance with utmost care, Jesus didn’t say an outright no, but asked them what they wanted Him to do for them. And then came the full truth: ‘You do not know what you are asking.’ Which is often the case with you and me; we want gains without the pains. Yet, it was not for Jesus to grant their request, but for God the Father to decide. The high place they coveted would be ‘for those for whom it has been prepared.’

This is so much the story of our own lives. As the saying goes, man proposes; God disposes. Although there is nothing wrong in proposing, this must be accompanied by a wilful surrender to the divine will. God’s will can be way different from our own, so we must be ready to accept it, firmly trusting that it will work for our good. The golden rule, then, is to believe that ‘there is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens’ (Eccl 3: 1).

Setting the common good above everything could be another guiding principle. Also, we must ascertain that our goal has a higher purpose. This sanctifies what we desire – power and glory included. If it be for God, let it be done! That is what a 300,000-plus gathering meant to say when they sang ‘We want God’, on John Paul II’s first visit to his homeland, in 1979, shortly after he succeeded to the Chair of Peter. He invoked the power of the Holy Spirit to renew the face of Poland and liberate it from the bondage of communism and atheism.[1] The prayer was transformative.

That is a perfect illustration of what those in power should do. Jesus pointed out that, unlike the Gentile rulers who lord it over their people, Christians must rule through selfless service. ‘Whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be slave of all.’ There is no better example of this than Jesus Himself, who came not to be served but to serve, not to live but to give His life as a ransom for us.

Finally, the Second Reading (Heb 4: 14-16) makes it clear that we must envision the ‘throne of grace’, where Jesus is seated, at the right hand of God the Father. Our High Priest sympathises with our weaknesses, so we can easily draw near to His throne, trusting that we will receive mercy and find grace. Which is so much unlike the earthly seats of power that are hotbeds of inconsideration, corruption and degeneration. Thus, there is not a doubt that only those who have gone through the passion are deserving of the glory.

Banner: The Sagrada Familia Basilica, Barcelona https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sagrada-Familia

[1] https://breakingground.us/we-want-god/

Where to lay up our treasures

We all wish to be happy, don't we? And everything we do is in high hopes of achieving happiness. The problem is when we don’t know what true happiness looks like. We look around and see wealth and possessions, power and influence, health and beauty, fancies and pleasures, knowledge and skills, and mistake them all for happiness. No doubt, they are blessings and they do make us happy; yet something feels incomplete. For sure, when we leave God out of the equation, we fail to balance the formula of happiness.

King Solomon, arguably the author of the Book of Wisdom, states that wisdom clinches it: ‘I preferred [wisdom] to sceptres and thrones, and I accounted wealth as nothing in comparison with her. Neither did I liken to her any priceless gem, because all gold is but a little sand in her sight, and silver will be accounted as clay before her. I loved her more than health and beauty, and I chose to have her rather than light, because her radiance never ceases. All good things came to me along with her, and in her hands uncounted wealth.’

So, wisdom it is that we must seek out so as to attain happiness. Wisdom is the ability to see things, through prayer, the way God sees them; it is a spiritual gift that enables us to discern God’s plan. St Thomas Aquinas says it is both the knowledge of and judgment about ‘divine things’, and the ability to judge and direct human affairs according to divine truth.[1] Like Solomon, when we aim for the sky, all that is under it is ours for the asking: when we seek God – who is Wisdom – the rest is added unto us (Cf. Mt 6: 33).

The rule applies to everybody without exception: parents and children, teachers and students, managers and employees rulers and the people, statesmen and their advisors, scientists and researchers, all professionals, the clergy and the laity, The world will be a better place if we take wiser decisions. Domestic quarrels, public scandals, intercontinental wars are often a result of misinformed or confused minds groping in the dark. Alas, some of them may be downright malicious in what they do, but others simply use the wrong means to achieve their ends. For instance, some may naively think that just having wealth will bring them happiness....

Here is probably where that well-meaning man of the Gospel text (Mk 10: 17-30) failed miserably. He had approached Jesus with an all-important question: ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’ Jesus referred him to the commandments: he had observed them all! Moved by his uprightness, the Good Teacher declared: ‘You lack one thing. Go, sell what you have… and come, follow Me.’ At that saying, the man’s countenance fell; he went away sorrowful, for he had great possessions. That is, his love for money had proved to be greater than his love for God….

It is sad that the man turned away. That line about him speaks volumes about the folly of rejecting a divine invitation and about continuing to wallow in the mire of the world. It is not that we must give up everything and head to the nearest monastery; rather, even while we follow our calling, we ought to be ready to make one heap of all our winnings and never breathe a word about our loss. It must be God’s will all the way, in what we do, wish, say. Jesus has to be the be-all and end-all of our existence; He who is Wisdom Incarnate has to be our supreme ideal!

Does that seem to be a tall order? Nothing is too big for Him who is the ‘Light of the World’ (Jn 8: 12). Let us learn to trust in Him. By our presence and word, let us spread His light and dispel fear from our disbelieving world. ‘Do not worry beforehand about what you are to say,’ says St Mark elsewhere, ‘but say whatever is given you at that time, for it is not you who speak, but the Holy Spirit’ (Mk 13: 11). The Second Reading (Heb 4: 12-13) pertinently notes that ‘the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and spirit.’

After all, wisdom is one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit; and the word of God, like a learned judge, is unyielding. He discerns the thoughts and intentions of the heart, and before him none is hidden. In fact, ‘we are open and laid bare to the eyes of the one to whom we must present an account,’ says the Letter to the Hebrews. So, why dilly-dally? Let us first seek the kingdom of God, discern His plan, and live by it. Wisdom will then bear abundant fruit.

Is the spirit willing but the flesh weak? Don't worry; let our hearts leap with joy on hearing the good news of salvation. The Lord has promised that our detachment from earthly treasures and the enduring of persecutions for His sake will gain us eternal life. So, how about laying up treasures in heaven rather than on earth? And on this day that marks the last Marian apparition at Fátima, let us pray that the good old Miracle of the Sun, which inspired thousands way back in 1917, convinces the world that God exists and that His salvation is for real.

Banner: https://prunedlife.com/lay-up-treasures-in-heaven/

[1] https://www.catholic.com/magazine/print-edition/the-seven-gifts-of-the-holy-spirit

Saving Marriage and Family

In a way, today’s Readings are about the survival of humankind. They dwell on the institutions of marriage and family, both of which are fundamental to society. And society is not a mere collection of physical bodies but of souls, while marriage, family and society are, not humanly, but divinely instituted. Which explains why, in a godless world, marriage and family are the first targets of the evil one. Marriage is demeaned by divorce; family life, by individualism. Both deviations are toxic and can lead to the death of humanity.

The Readings of today could not be clearer. A comment on God’s creation of man and woman comes in the very second chapter of the Book of Genesis. The relevant text which makes up the First Reading (Gen 2: 18-24) highlights that, to make a helper fit for Adam, no beast nor bird was of avail. Finally, God made Eve, a woman, out of the man’s rib, causing Adam to remark: ‘This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh.’

A story we lapped up as children has now become the butt of criticism. In a so-called rational and secular world, are we, then, still to believe the traditional story of creation? Yes, for in the ultimate analysis there is no quarrel between religion and science: truth is one. The Biblical account is not a text of physics or biology all right; it does not have the answers couched in modern-day parlance. Similarly, the Big Bang theory, for example, is just that – a theory! Devoid of clinching evidence, it is at best a scientific story.

That is not all. Theories such as these are likely to remain inconclusive till the end of times, as a vindication of the omniscience, omnipotence and omnipresence of God. In this regard, Cardinal Ratzinger, in In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall, cites Albert Einstein, who said that in the laws of nature ‘there is revealed such a superior Reason that everything significant which has arisen out of human thought and arrangement is, in comparison with it, the merest empty reflection.’[1]

Some may demand to know why God created man and woman in the first place. He did so according to His wisdom and moved by genuine love. ‘God created man in His image; in the divine image He created them; male and female He created them’ (Gen 1: 27) And ‘therefore a man leaves his father and mother and cleaves to his wife, and they become one flesh’ (2: 24). God blessed them, saying, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it’ (1: 28). That was the divine sanction for marriage.

In the Gospel (Mk 10: 2-16) we see how Our Lord was especially attentive to the issue of marriage. The Pharisees, in a bid to test the Divine Master, quoted Moses, who had said it was lawful for a man to divorce his wife. Jesus retorted that the Prophet said so in view of their ‘hardness of heart’, or obstinacy. Then, condemning divorce in no uncertain terms, Jesus said: ‘What God has joined, let not man put asunder.’ The same applies to the family, which is in the throes of an unprecedented crisis created by sinister agencies.

Past Popes, in their encyclicals, allocutions, apostolic exhortations and other documents on the subject, staunchly stood by Our Lord’s teachings. But alas, by and by, the world began to rationalise and relativise those unequivocal teachings. Soon, the purpose of bringing forth new life, through man and woman’s participation in God’s creative love, got thwarted. Gender identity have got reinterpreted and gender roles challenged – yet another form of the proverbially ominous cry of the fallen angels: Non Serviam (‘I will not serve’). It is therefore important that the Church earnestly catechise the faithful on the nobility of marriage and family. Her efforts would go a long way towards reducing the number of annulments (hopefully, not a euphemism for ‘divorce’) granted by ecclesiastical tribunals.

It is a pity that, influenced by evil forces, the modern, rational man keeps making irrational decisions! Some of our sins cry to heaven for vengeance. As for God, in His eternal love for His supreme creation, He sent His Son to the world. Jesus deigned to become lower than the angels – He became man, and ‘by the grace of God tasted death for everyone,’ as the Second Reading (Heb 2: 9-11) reminds us.

Jesus is the New Adam; His Mother, the New Eve. We must turn to them in fervent prayer, to save the traditional institutions of marriage and family: ‘May the Lord bless us all the days of our life’ (Ps 127).

Banner: https://shorturl.at/Apnu2

[1] Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall (1990), transl. by Boniface Ramsey, O.P., p. 23.

God’s Spirit in our Hearts

While Moses wished all people were prophets and Jesus welcomes those that are in alignment with His commands, the Epistler St James comes down heavily on the worldly wise, for Heaven is what they risk losing.

The First Reading (Num 11: 25-29), taken from the Book of Numbers,[1] focusses on the string of complaints that the Israelites had about the hardships faced enroute and against Moses. When Moses finally threw up his hands, God directed him to select 70 elders to assist him in governance. At a ceremony held at the Tabernacle,[2] they were filled with Moses’ spirit, following which they began to prophesy. This act prefigured the Sacrament of Holy Orders.

The prophesying of old was replete with exotic and ecstatic manifestations. But the point here is that two elders, Eldad and Medad, who for unknown reasons did not attend the initiation, began to prophesy anyway. Of course, while not all are bestowed the gift of prophecy, God is free to grant it to whoever He deems fit. In other words, ‘the wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So is it with everyone who is born of the Spirit’ (Jn 3: 8).

But that did not prevent jealousy from raising its head. Moses therefore says to his aide Joshua, who was the complainant: ‘Are you jealous for my sake?’ These words can be disturbing if jealousy is equated with envy. While jealousy arises from love of persons or things we possess, envy is sorrow felt about something that others enjoy and we crave for. Interestingly, St Thomas Aquinas breaks jealousy down into ‘love of concupiscence’ (which is selfish) and ‘love of friendship’ (selfless).

To give Joshua the benefit of doubt, we may see his jealousy not as concupiscent, selfish love but as friendship,selfless love. Joshua was not competing with the duo but had objections to what he regarded as insubordination. Joshua’s attitude speaks volumes of his zeal for protocol, love for, respect to and obedience of authority. In our times, we could take this to mean lovingly upholding the perennial Magisterium of Holy Mother Church.

In fact, Joshua’s life was one of discipleship; and after the death of Moses, he led the tribes of Israel in the conquest of Canaan. For his part, Moses expressed the wish that all would receive the gift of prophecy: ‘Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets, that the Lord put his spirit upon them!’ Centuries later, the Christians were filled with the Holy Spirit at the first Pentecost.

That the Gospel text (Mk 9: 38-43, 45, 47-48) should bear a striking resemblance to happenings of some two millennia earlier only goes to show that human nature never changes. When John told Our Lord that he had forbidden a non-disciple from casting out demons in His name, Jesus very simply instructed him to refrain from doing so: ‘Do not forbid him; for no one who does a mighty work in My name will be soon after able to speak evil of Me. For he who is not against us is for us.’

Thereafter, praising innocence like that of a child he was holding, Jesus stated that whoever causes the little ones who believe in Him to sin, ‘it would be better for him if a great millstone were hung round his neck and he were thrown into the sea.’ Strong words, followed up by stronger ones: if one’s hand or foot or eye be the cause of sin, cut or pluck them off, He said – for it’s better to enter heaven maimed than to be in one piece and go to hell.

It is not that Jesus decries institutional or formal arrangements and acclaims informal ones; He only impresses upon His disciples not to be stiff and ‘square’ but, rather, to play it by ear. He urges you and me to set our minds and hearts on Heaven; after all, nothing else matters as much. We have to go about our daily chores happily and fulfil duties to the best of our abilities, but at the same time prize heaven above earth.

In this context, St James the Great in the Second Reading (Jas 5: 1-6) comes down heavily on the wealthy who are charmed by material riches, and, to satisfy their greed, grind the faces of the poor. Once again, sharp words addressed to the likes of them: ‘You rich, weep and howl, for the miseries that are coming upon you… you will eat your flesh like fire.’

One is reminded of Mephistopheles who says sadistically to Dr Faustus in Marlowe’s play of the same name: ’Tis too late, despair, farewell! Fools that will laugh on earth, most weep in hell.’ For sure, none of us wish to be counted among their number. Let us therefore quickly choose to have God’s spirit in our hearts and be at peace with our consciences by fulfilling God’s commands: the precepts of the Lord gladden the heart (Ps 18" 8).

[1] It is the fourth book of the Pentateuch, common to the Torah as well. Its name comes from the two censuses of the Israelites: one taken upon leaving Mount Sinai, and the other, when at the doorstep of the Promised Land of Canaan.

[2] Also called ‘Tent’, it referred to the portable sanctuary that Moses had built to be a place of worship for the Hebrew tribes during the period of wandering before their arrival in Canaan. The arrangement became redundant after the erection of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem in 950 BC.

Have we lost our Way?

The history of Christianity has had its ups and downs, its own share of joys and sorrows. Through it all, the coming of the Son of God into the world and His rising from the dead have become the bedrock of our faith and our only hope.

Jesus Christ conquered the world albeit His own had rejected Him. He was crucified; and as though one crucifixion was not enough, we keep crucifying Him every single day. And alas, it is shocking that Christ’s foremost representative on earth put a spin on His divine declaration: ‘I am the Way, the Truth and the Life. No one comes to the Father except through Me’ (Jn 14: 6).

Many ‘ways’?

Jesus has categorically stated that He is the only path to salvation and eternal life. Yet, on a recent visit to Singapore, Pope Francis, going against two millennia of Catholic teaching, put forth the idea that ‘every religion is a way to arrive at God…’. Not only did he say that there are different ‘ways’, he failed to name Jesus as being the God arrived at!

You and I believe that Christ is the only Way and the sole reason why we are Christians. Nonetheless, some fainthearted souls encountering newfangled ideas may suddenly see no point in trudging the challenging path of Christianity… They have just been tempted with a fruit bowl of religions, haven’t they? What, then, is the point of our faith, they might ask, if people of all beliefs can easily arrive at the Beatific Vision?

It is a pity that the tenets of our faith are being despised, not to say wilfully distorted by those at the helm. A foundational teaching has been very unceremoniously cast away! And we might soon begin to believe that agnostics and sceptics, atheists and satanists, too, are in the know of a secret way to Heaven! A sorry state of affairs that brings tears to one’s eyes…

In short, supernatural revelation has been brushed aside. Which straightaway makes divine grace non-existent, the Sacraments empty, evangelization meaningless, martyrdom and sainthood a fraud. What a far cry from what the Church has taught down the ages! This is a sure shot scheme to scatter the sheep, causing turmoil and distress in the fold.

Indefensible

It is anybody’s guess why the Pope made those outrageous public statements in the tropical island city-state of Southeast Asia. Was he playing to the gallery in a country with large pockets of at least five religions?

Instead, is he is not expected simply to proclaim Jesus? If the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church doesn’t show the way, who will?

Many theologians have dubbed those utterances heretical. And unlike diplomats and politicians who attribute their gaffes to a slip of the tongue, misreporting or mistranslation, the Vicar of Christ doubled down on what he said, showing no qualms about having contradicted the Son of God.

Some allege that only ‘traditional Catholic quarters’ have taken exception to the Pontiff’s statements. The fact of the matter is that it can by no means be seen as a dispute between conservatives and liberals, traditionalists and progressivists, for the Patriarch of the West has hacked at the very foundation of Christianity.

How were the Pope’s indifferentist views received by other religionists? Polytheistic religions may not find the views offensive but monotheistic religions find religious pluralism proposals subversive. The Pope’s efforts may even come to be regarded as veiled poaching.

Of course, there are those who have hailed his break from the traditional interpretation of Jesus’ seminal statement. Such thinkers should rather quit the Church and start their own club. When not even secular institutions, however liberal, will ever entertain fifth columnists, why should the Church permit misinterpretation or twisting of her doctrine?

Be that as it may, self-respecting Catholics should watch out for a fresh salvo of secularist/irreligious cannon fire at the Synod on Synodality coming up in October this year.

End Times

The march of events in the last decade have been quite mystifying. Who can tell what else is in store for us? But then, ‘there is nothing hidden that won't be revealed, and there is nothing secret that won't become known and come to light’ (Lk 8: 17).

We are faced with a pontificate that is arguably one of the most controversial in modern Christian history. Almost every second interview or encyclical of the present pontiff has been contested, be it by cardinals, theologians, or other specialists.

Under the circumstances, it is very important to consider if we have lost our way…

This chaos, humanly speaking, may sound the death knell for the Church. At this rate, she might be replaced by a human-centred, New Age religion and church far removed from Christ. The saving grace is that the Church founded by Jesus Christ is both human and divine, and we have Our Lord’s promise that the gates of hell will never prevail against her.

Similarly, from our Blessed Mother we have this assurance: ‘In the end, my Immaculate Heart will triumph.’ These words addressed to the shepherd children of Fátima in 1917 are a beacon of hope amid the present warmongering, both literal and metaphorical.

But none of that can justify self-complacency or passivity on our part. Rather, our response should consist of prayer and action. And teetering as we are on the brink of a world war, who knows if, when we least expect it, a one-world government and a one-world religion will be foisted on us as being a magic solution (similar to the vaccine against the once dreaded Covid-19 pandemic)!

In fact, in view of the unprecedented state of world affairs, many people have begun to wonder if we are living in the end times. Let us therefore continue to submit ourselves to the perennial Magisterium of Holy Mother Church, steadfastly following Him who is the Way, the Truth and the Life, and serenely awaiting the justice of God in the voice of history!

Banner: https://rb.gy/lxowxs

Walking in His Footsteps

It is amazing how the liturgical Readings very often map our thoughts and feelings, from day to day and week to week. God speaks to us in the midst of our daily life, our joys and aspirations, our trials and tribulations. The Holy Scriptures thus remain eternally relevant.

Today’s Readings speak of the battle of good and evil continually taking place in the private and public consciences. They forewarn us of the difficulties we would encounter, inviting us to reflect and change our ways for the better. What happened to Our Lord happens to each and every one of His followers. We must keep the faith and never trade it.

It is well known that a sinner, even if just contemplating to change his ways, soon becomes a prey for the devil. In the First Reading (Wis 2: 12, 17-20) the godless say to themselves, ‘Let us lie in wait for the righteous man, because he is inconvenient to us and opposes our actions; he reproaches us for sins against the law, and accuses us of sins against our training.’ The virtuous person is hated and his path paved with thorns.

The said Reading anticipates Our Lord’s experiences. He was Truth personified – and all the more prone to be tempted by the evil one. ‘For if the righteous man is God’s Son, He will help him and will deliver him from the hand of his adversaries.’ Don’t these words evoke the devil’s temptation of Our Lord on the mountain?

Of course, those words were fully realised later in the life of Our Lord: He was insulted, tortured and condemned to a shameful death.

In today’s Gospel (Mk 9: 30-37), Jesus says: ‘The Son of Man will be delivered into the hands of men, and they will kill him.’ Thankfully, He added: ‘after three days He will rise.’ His disciples did not understand the saying, and they were afraid to question him. What about us, at the end of two thousand years?

If we were to draw up a balance sheet today, we would undoubtedly say that the present situation leaves a lot to be desired. We are losing focus, losing track. For instance, recently, none other than Our Lord’s foremost representative on earth completely disregarded Our Lord's words about His being ‘the Way, the Truth and the Life’. (Read my blogpost titled ‘Have we lost our Way?’)

Finally, the Second Reading (Jas 3: 16; 4: 3) also hits the nail on the head when it says that ‘where jealousy and selfish ambition exist, there will be disorder and every vile practice.’ Today, St James pointedly asks world leaders, and us as individuals, groups and communities: ‘Where do the wars and where do the conflicts among you come from?’

Clearly, they come from our passions, which are futile if not managed properly. Jesus’ cousin concludes that, as a result of our warring passions, ‘you covet but do not possess. You kill and envy but you cannot obtain; you fight and wage war. You do not possess because you do not ask. You ask but do not receive, because you ask wrongly, to spend it on your passions.’

So, where do we go from here? We ought to go back to today's Gospel passage where Jesus presents the innocent child as a model. ‘Whoever receives one child such as this in my name, receives me; and whoever receives me, receives not me but Him who sent me.’ This may sound foolish to the world, but then, who can deny that worldly wisdom brings envy and selfish ambition whereas divine wisdom brings peace and righteousness? We may really not achieve it up to the hilt, but we will have made an attempt. And that is what pleases God.

Christian leaders and faithful need to serve our Divine Master and the community – and do so loyally, faithfully. The world prizes unbridled success – name, fame, popularity, power and influence – but in God’s eyes, there is no success without sincerity and devotion, loyalty and faithfulness. Life is not a numbers game; it matters not how many times we fall but how quickly we get up and walk in the footsteps of Him who is the Way, the Truth and the Life.

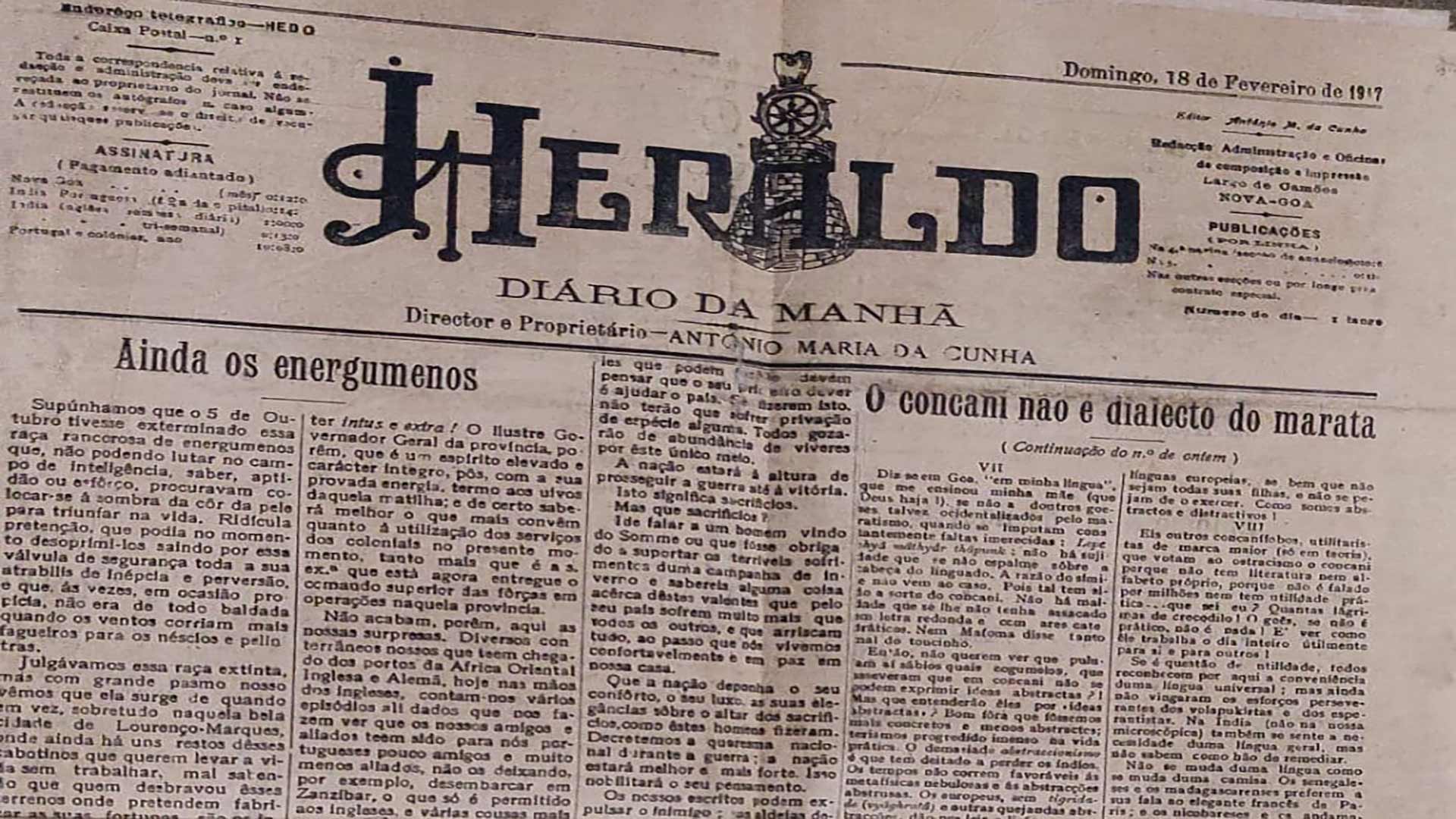

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 8

Part 8 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata" – Parte VIII

by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

(In Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2575, 18 February 1917, p. 1)

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

Here are other Konkaniphobes, major utilitarians (only in theory), who ostracise Konkani because it has no literature or alphabet of its own; because it is not spoken by millions nor has any practical use… what do I know? How many crocodile tears! A Goan, if not practical, is nothing! One must see how usefully he works all day for himself and for others!

If it is a question of utility, everyone recognizes over here the convenience of a universal language; but the persevering efforts of the Volapukists and Esperantists are still not vindicated. In India too (not in our microscopic one) the need is felt for a general language, but one knows not how to resolve it.

You can't change your language like the wind. The Senegalese and the Malagasy prefer their speech to the elegant French of Paris; and the Nicobarese and the Andamanese give more value to their speech than to the booming English of London. The Hottentots and the Zulus would not give up their sibilants and monosyllables for the best language in the world.

A self-respecting son does not subrogate his mother, however ugly, poor, ragged, pustulous, for a queen, beautiful as Venus, adorned with byssus and purple, with diamonds from Golconda, pearls from Ceylon and rubies from Pegu. He doesn't ‘kick’ her, as they say there; he doesn't reject her, loathe her; he hugs her, kisses her, helps her, boosts her, lavishes her with all the care and indulgence he is capable of. This is what St John Chrysostom teaches us, speaking of children, who in many ways are our teachers. Or else, the Son of God would not have said: Unless you become like little children, you will not enter the kingdom of Heaven.

I won’t be surprised if over there they know not that in Kanara there is a language, sandwiched between Malayalam (language of the Malabar) and Kannada; it has no literature, no alphabet of its own, is spoken only by five hundred thousand, is stuffed with Sanskrit, Kannada, Malabarian and Hindustani words. It is Tulu or Tulava, which bears more Portuguese terms and closer relations to Konkani than Kannada does. In the opinion of Caldwell and other grammarians, it is nonetheless one of the more developed of the Dravidian family. And till date no one has proposed that it be replaced by one of its more powerful neighbours that lend it their alphabet. On the contrary, Protestant missionaries promote it diligently, by publishing grammars, dictionaries, and other works.

If, however, Goa’s progress and happiness depend on Marathi being the vernacular and vehicle of primary education, may a Hercules arise who will do away with the Konkani hydra; and I will only have to sing his praises, mimicking Pasquin: Quod non fecerunt lusitani, fecerunt canarini.

And then, let's hope that some Nobel prizes will end up in our homeland, as did one, two years ago, in Bengal (to Sir Rabindranath), and that there will emerge an authentic genius, like Chandra Bose, who astonished scientists of Europe and America with those wonderful demonstrations of plant physiology.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, Sep-Oct 2024, pp __

Leap of Faith and Love

Last Sunday, a seventy-year-old shared with me some of her longstanding questions about religion and faith. She is presently beset with physical ailments, and finds it painful to turn them over in her mind. Hers has been quite a long journey, and fearing that it may end abruptly, she asks: ‘What does it take to be saved? Can I simply have faith in Jesus and be saved?’ While this is in itself a worthy act of surrender that will be pleasing to the Lord our God, there are a few nuances to be considered in this regard.

Quite remarkably, today’s Readings point exactly to what it takes to be saved. And this is no coincidence, for He who feeds the birds in the blue sky and the worms in the garden soil, always provides the answers we seek. And as I get down to writing this blogpost, I hear in the background this Merle Haggard song, which I dedicate to all who are on the journey of faith –

I come to the garden alone

While the dew is still on roses

And the voice I hear falling on my ear

The son of God discloses.

And he walks with me and he talks with me

And he tells me I am his own

And the joy we share as we tarry there

None other has ever known.

He speaks and the sound of his voice

Is so sweet, the birds hush their singing

And the melody that he gave to me

Within my heart is ringing.

Let us therefore remember that we are never alone; God is with us and speaks to us at all times, as he did to Isaiah of old. In fact, in the First Reading (Is 50: 5-9), the Prophet says, ‘The Lord has opened my ear, and I was not rebellious. I turned not backward… For the Lord God helps me; therefore, I have not been confounded; therefore, I have set my face like a flint, and I know that I shall not be put to shame; he who vindicates me is near.’

Indeed, whoever trusts in the Lord has nothing to fear. We may be surrounded by the snares of death and anticipate the anguish of the tomb; we may be in the throes of sorrow and distress, yet when we call on the Lord’s name, He will deliver us. He is gracious, compassionate; He protects the simple hearts and saves the helpless. The psalm antiphon therefore invites us to sing with confidence: ‘I will walk in the presence of the Lord in the land of the living.’ We are called to be ever conscious of and grateful for the Lord's presence in the humdrum of our lives; He knows and cares for our every need. No wonder the Psalmist is all praise for the Lord’s mercies.

Even so, often we are ungrateful, as the Jews were, to Jesus. He who had come down from Heaven and wrought signs or miracles, as expected, was rejected by His own. ‘Who do men say that I am?’ He asked. What is our answer to that question that Jesus asks in the Gospel today (Mk 8: 27-35)? Have we have built up a personal relationship with Jesus, as He journeys with us, quietly bearing all our burdens? Only Peter answered correctly – ‘You are the Christ’ – yet when the Master spoke of suffering and rejection and death on the Cross and of rising from the dead, Peter rebuked Him. And Jesus was quick to dub him ‘Satan’, whom he ordered to get behind Him.

This was the first time Jesus was presenting Himself as the Suffering Messiah. There was ample evidence that He was indeed the Son of God, whose horizon was none other than the heavenly kingdom. But the people did not quite understand; they wanted Jesus to care about their earthly kingdom and do away with the Roman subjugation of their nation. As a result, Jesus both disappointed the Jews and angered the Romans. He taught the disciples that the Son of Man would have to suffer many things – and so would those who wished to follow Him.

‘Whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake and the Gospel’s will save it’ can easily be put down as one of the greatest of the Kingdom paradoxes. Here is how worldly logic does not align with God’s wisdom; here is also how our faith does not align with reason. Not that they are intrinsically antithetical. Faith and reason are compatible, and so are science and religion, because truth is but one. Sadly, it is our egos that upset the apple cart; while in faith, we put our hope and trust in God, in reason we seem to trust more in our own powers, and only belatedly realise our folly.

Is Faith alone, then, our salvation? St James in the Second Reading (2: 14-18) states: ‘Faith by itself, if it has not works, is dead.’ Indeed, the Church rejects the ‘faith alone’ proposition, meaning that intellectual faith cannot save us. One needs to cooperate with God’s grace. Rather, our hearts have to move too. And this stirring will ensure that all that we do is out of love: corporal works of mercy[1] and the spiritual works of mercy[2]. That is to say, our faith must be wrapped up in love (charity or supernatural love of God). That is the right leap to take, and the time is now!

[1] Feeding the hungry; giving water to the thirsty; clothing the naked; sheltering the homeless; visiting the sick; visiting the imprisoned, or ransoming the captive; burying the dead.

[2] Instructing the ignorant; counselling the doubtful; admonishing the sinners; bearing patiently those who wrong us; forgiving offences; comforting the afflicted; praying for the living and the dead.

Goencheo Mhonn'neo - IX | Adágios Goeses - IX

Segue uma nona lista de adágios,[1] extraídos do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (1872-1935)[2].

- Concani | 2. Tradução literal | 3. Tradução livre

1. Xelyá angar bibó. | Xellia angar bibo.

2. Sobre o corpo são,

suco de anacardo

(p’ra causticação).

3. Ter injusto sofrimento

ou pena, sem fundamento.

1. Venttó laslyar, vôll vhossó na. | Vennto laslear voll vochona.

2. Uma corda torcida

estando até queimada,

a sua torcedura

não fica desvincada.

3. Apesar de estar punido,

não fica ele corrigido.

1. Duddú nant taném tarir poiló bossunk zay. | Duddu nant tannem tarir poilo bosunk zai.

2. Numa barca de passagem,

deve meter-se primeiro

quando alguém, para pagar

o nauta, não tem dinheiro.

3. Quem não tiver protecção

deve ir sempre, antes de outros,

fazer sua petição.

[1] Cf. oitava lista, Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 29, julho-agosto de 2024, p. 51.

[2] Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda, Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), com acrescentamento dos adágios na grafia moderna, pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, Sep-Oct 2024, pp __