Herald at 120!

I'm a fourth-generation reader of Goa's first daily. As much as I grieved the loss of the Portuguese edition in 1983, I looked forward with great anticipation to Herald as we know it today. Its arrival was timed to more or less coincide with the Commonwealth Heads of Government Retreat in Goa, which the paper then covered most delightfully. Eventually, Herald acquired a great reputation, thanks to its sustained campaign for recognition of Konkani as official language and Statehood for Goa. The paper has since been firmly ensconced in the heart of every Goan. I sincerely hope that Herald will continue to earn the trust and confidence of its readers and writers and forever be a people's paper par excellence.

(Herald, 26 January 2020, p. 22)

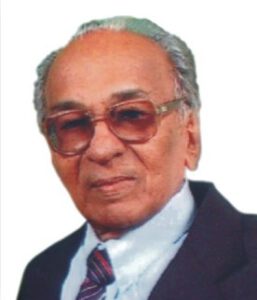

Tribute to my Father

Early this month the social media was abuzz, in anticipation of the twenty-twenties; as for me, I was on a solo trip back to nineteen-twenty. As a child, this year had the earmarks of a happy milestone for me, yet it triggered anxiety for the future. My childhood was a shrine of happy pictures, yet the thought of that golden marker fading into the horizon would fill me with sadness. Why? Because while a young me was looking ahead to what would be, my father Fernando was already looking back upon what had been….

My lone source of anxiety for the future was that I was the eldest child, born in Papa’s forty-fourth year. I knew not how long I would have him: it was a worry I kept to myself so as not to dishearten him. But then, hardly anything disheartened him; he kept pace with his children and even his grandchildren’s progress, and enjoyed the sleep of the just. When he passed on, at 91, he was a grandfather to fifteen. His abiding trust in God was the secret of his longevity – as well as a salutary lesson on the futility of anxiety.

In my naiveté, 1920 still felt charming; as I grew older, I found Papa’s idealism, independence and integrity appealing. I looked up to him, especially because his life hadn’t been easy: the ‘roaring twenties’ of the West had played out quite differently in Portugal and Goa. Following a decade of political turbulence and galloping inflation, the country stabilised and the escudo roared upon the rise of Salazar the economist. Convinced that he was a man with ‘the right intention’, my father held him in esteem for his intellect and honesty – the antithesis of leaders in sham democracies.

After God, it was Goa uppermost in Papa’s mind. The Mass and the Bible alongside spiritual classics were his daily fare. To compensate for arid bureaucratic matters, he put his faith in reading, writing, teaching and music. Even while he took delight in the Romantics Eça, Camilo and Ramalho, he recommended some excellent Goan writers. Until his last breath he lapped up the masters of the Portuguese language, not forgetting two of our very own Goan purists, Costa Álvares and Filinto C. Dias.

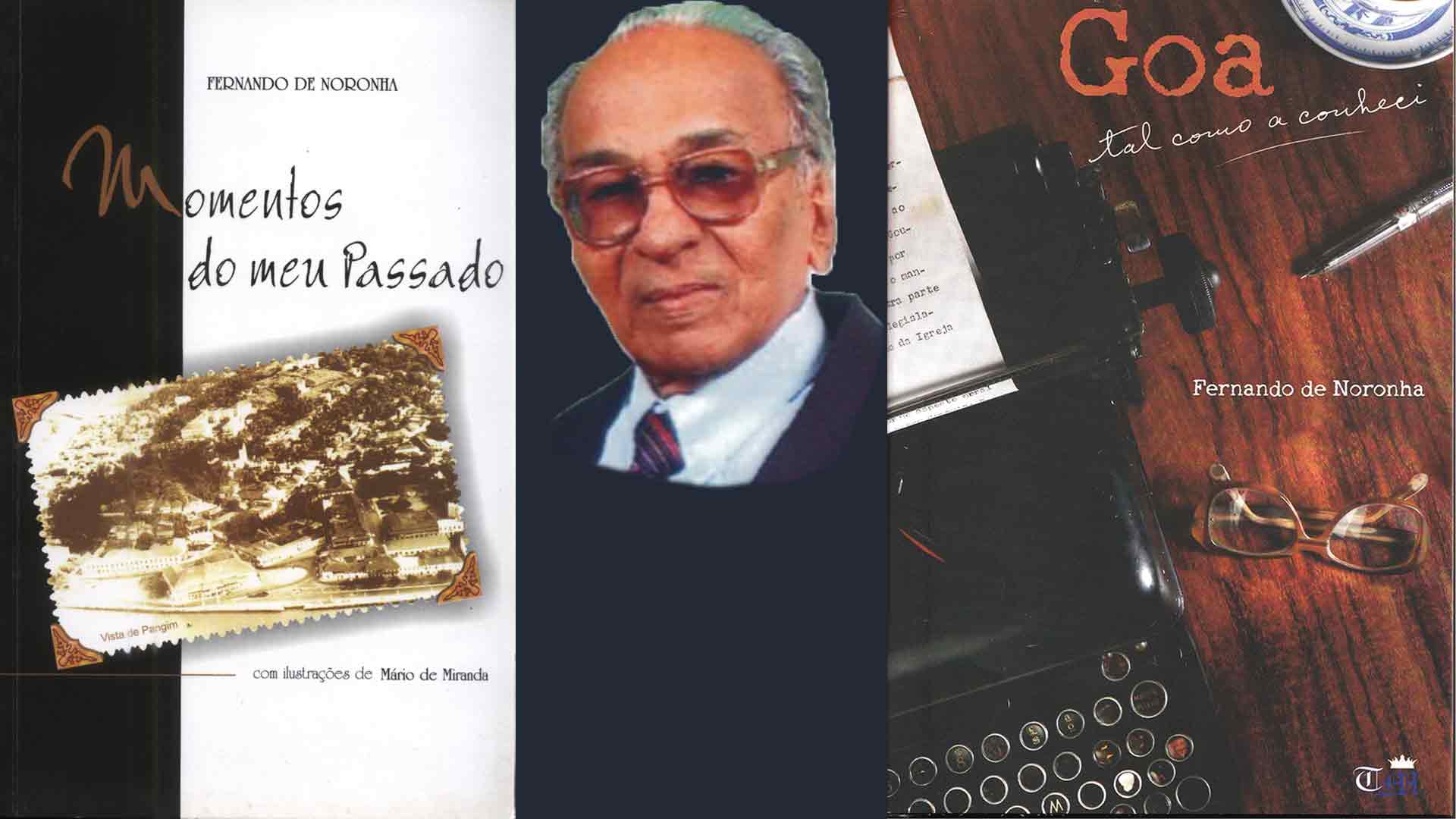

One gets a bird’s eye view of Papa’s outlook from his first book, Momentos do meu Passado (Moments from my Past). Much of it is what he used to recount animatedly at the dinner table or talk over with relatives and friends. He obliged us by writing this slim volume comprising ‘figures, facts and facetiae’: pen sketches of over thirty personalities from the Goan social and political milieu; some little-known facts of contemporary history; and a host of anecdotes dating back to his Lyceum days. In his words, he wished ‘to quench saudades of a not so distant past, when one lived in a happy and carefree manner unique to Goa.’

It took me some time to appreciate Papa’s simple and straightforward nature. And noticing how people would often agree but also end up severing ties with him, I learnt that truth can indeed puzzle, confound, hurt… Papa’s intermittent observations on public affairs are lost in the thicket of Heraldo and A Vida for, whilst a bureaucrat in two key departments during the Portuguese regime, he used pen names of which he kept no record. In 1967, his commitment to ferry people to the booths on the occasion of the Opinion Poll (16 January, his birthday and feast of St Joseph Vaz) fetched him a resounding office memo.

It warms the cockles of our hearts to see that Papa’s second book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), contains the essence of his views on people, events and ideas. Covering as he did twentieth-century Goa’s political and administrative affairs, society, culture, and religion, in a total of eighteen chapters, this offering is a testimony of love for the land and the people. It is also a tribute to the Portuguese language that was so dear to him. After opting to retire from public service, he taught that idiom at a city college and co-founded a weekly, A Voz de Goa. At Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church he prayed in that ‘language of the angels’ and put together a choir at Sunday mass.

Music was high up on his agenda ever since his father purchased a gramophone and a maternal uncle and self-taught violin virtuoso played along. An attractive feature of Papa’s day was his whistling and playing of the harmonica, providing the household with a kind of crash course in classical and semi-classical music. The mandó moved him very especially (he ensured that it featured at his children’s wedding parties) and so did two popular Konkani films of his time which, he said, ‘foster Goan patriotic feelings’. The Goan reality, however, was a far cry from what he had envisioned, so I can say with Wodehouse that ‘if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.’

No tribute to our father would be complete without a reference to our dearest mother Judite da Veiga, who was the love of his life, the reason of his being. On his death bed I heard him thank her for half a century of togetherness. She, their five boys and families, was all that he ever wanted. We have lost him in body, not in spirit. He has become greater in death, our strength and consolation, our conviction that there can be no anxiety for the future….

Herald, 19.01.2020, published an abridged version

For this full version see Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), March-April 2020

https://issuu.com/casadegoa/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n3_-_mar-abr_2

When the soul feels its worth…

Does the run-up to Christmas sometimes feel like a wild-goose chase? When the painters don’t show up; the newest dress catalogue is a let-down; the much-awaited mechanized crib is a non-starter, and there’s no Christmas tree and star worth the name in the city shops... As if that weren’t enough, there’s no turkey in town, and we have to literally start chasing geese!

Does the run-up to Christmas sometimes feel like a wild-goose chase? When the painters don’t show up; the newest dress catalogue is a let-down; the much-awaited mechanized crib is a non-starter, and there’s no Christmas tree and star worth the name in the city shops... As if that weren’t enough, there’s no turkey in town, and we have to literally start chasing geese!

‘A poor life this if, full of care, we have no time to stand or stare,’ W. H. Davies would say. Alas, the weariness, the fever and the fret increases by leaps and bounds as we draw closer to Christmas. There’s a mad rush online, long queues at the mall, frightening street jams, hullabaloo at home. It is as though the celebration is an end in itself.

Isn’t Advent supposed to be a time of expectant waiting and preparation for the Nativity of Jesus? Flippant though it may sound, today it’s more about waiting for Flipkart orders to arrive and set the tone for the Christmas preparation. Where, then, is that time to stand and contemplate the Babe of Bethlehem?

They say the best part of the celebration lies in waiting for it; but that’s only for those who can wait! On four Sundays preceding Christmas, candles are lit, representing hope, faith, joy and peace, all part of a tradition rich in symbolism. Sadly, with a decline in our capacity for spiritual expectancy and enjoyment, we simply gloss over those milestones. We are a generation of instant, material gratification.

It would be interesting to figure out how to spend this time of the year more meaningfully. To my mind, the accent should be on being ourselves rather than doing a million things. For sure, we must have put up the crib, the tree, the decorations; we do need the bells, the light and the music; and without the gifts and the family dinner, Christmas may feel incomplete.

But then, these acts should be symbolic of our self-giving to the Child Jesus; they should not be about self-serving. Those acts should finally translate into works of love towards our fellow human beings, and not make us complacent.

Pope Francis’ recent exhortation on how to spend Christmas is reassuring: we have to incarnate Christmas. For instance, one way to personify the Christmas pine is to resist life’s vigorous winds. We will bring alive the Christmas decorations when an array of virtues adorn our life. Jingling bells must be an invitation to one and all to gather and feel as one.

There is no doubt that the angel, the star and the Magi are some of the most enduring images of the Christmas tableau. Like the angel who sang ‘Gloria in Excelsis Deo’, we have to be harbingers of peace, justice and love. We have to be a guiding star to persons seeking the true God. In all that we do, we have to do as the Wise Men did: give the best of ourselves to the Lord.

When our being is one harmonious whole, our voices will produce the joyous music of Christmas. We will become instruments of peace and harmony in society. We will be the light of Christmas, illuminating others’ path with kindness, patience, joy and generosity. Our life will be a gift to everyone in need. The season’s greeting cards will magically convey our tender love and care.

And when everything is said and done and our Christmas dinner is underway – shared with someone who has no dinner to share with us – we will experience the presence of the Divine Infant in our midst. That night will be an expectant waiting and preparation for a new dawn, a new hope, a new life... Then there’ll be no wild-goose chase; we will be at peace with ourselves, thankful to God for what we are and what He has given us. Focused on Christ, we will be the salt of the earth and the light of the world.

Eventually, thoughts of how life had been a mad, mad rush in the bleak mid-winter, that is, “till he appeared, and the soul felt its worth,” will warm the cockles of our heart. From then on, every day it will be Christmas.

(The Goan, 25.12.2019)

Simple and Sublime

The Christmas tableau is a heart-warming story in miniature. As a child I was moved particularly by those poor shepherds huddled up on the cold hills of Bethlehem; they were the only ones to hear “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” that mystical night. I was also enthralled by the Magi, whose regal aura perfectly balanced out the divine narrative. After all, Jesus not only descended from the House of David, he descended from Heaven and made his dwelling among us. Here was real majesty, with no hint of extravagance.

The Christmas tableau is a heart-warming story in miniature. As a child I was moved particularly by those poor shepherds huddled up on the cold hills of Bethlehem; they were the only ones to hear “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” that mystical night. I was also enthralled by the Magi, whose regal aura perfectly balanced out the divine narrative. After all, Jesus not only descended from the House of David, he descended from Heaven and made his dwelling among us. Here was real majesty, with no hint of extravagance.

With two thousand years of the Nativity behind us, we surely have the benefit of hindsight. The multitude then perhaps failed to appreciate the wondrous event; and the few enlightened ones were so meek and mild that the likes of Herod exploited the situation, apparently frustrating God’s plans for humankind. The king and his minions even drove Christ to his death but, thankfully, his resurrection soon became the very foundation of the Christian faith.

There was a mighty coherence to Jesus’ life story. His rise from the tomb established his reputation as a Man-God. Were it not for Easter, Christmas would have gone down in history as a non-event. In fact, the Bible does not specify Jesus’ date of birth; and in the first two centuries, none paid attention to it anyway, as birthday celebrations were considered a pagan custom. Saints and martyrs were remembered on their day of death, which marked their entry into Heaven. Hence, theologically, Easter ranks higher than Christmas.

However, considering the tender feelings that birth evokes, Christmas was poised to be a cherished day. Based on patristic sources that dated Jesus’ conception (and crucifixion) to 25 March, St Hippolytus of Rome (c. AD 204) was the first to explicitly assign Christmas to its current feast day. For their part, the Romans had long been observing 25 December as Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (‘birthday of the unconquered sun’), so when in AD 325 Constantine I, the first Roman Christian Emperor, declared Christmas a holiday, the relation between the rebirth of the sun and the birth of the Son of God became more than obvious.

Half a century later, Pope Julius I formalised the date; yet Christmas would continue to be celebrated in close association with the day of Jesus’ baptism (6 January) for a long time to come. On this day some Eastern Orthodox Christians still observe Christmas side by side with the (revelation of the Infant Jesus to the Magi), while in accordance with the Julian calendar, Greek and Russian Orthodox churches commemorate Christmas on 7 January.

Celebration of Christmas struck root in the medieval ages. It gained impetus with Charlemagne’s crowning on that day in AD 800. The century also saw the creation of a special Christmas liturgy, although not on a par with that of Good Friday and Easter. But by and by Christmas developed a unique, visible identity, not least with the pine tree planted by St Boniface, as a pointer to Heaven; the old tradition of carol singing that was lent a heavenly form by St Bernard of Clairvaux; the crib, invented by St Francis of Assisi as a means of imparting the Christmas story, and so on.

Curiously, the more Christmas gained acceptance, the more it began to vary across countries, social and political eras, and Christian denominations in the post-Renaissance period. With changing values and norms, new customs were born while some of the older ones just hung on: the eye-catching star, the bright little candles, the sweet-sounding bells, and the intimate, family dinner, to name just a few elements that over time ensured that the divine occurrence became instantly relatable across cultures.

Christ’s coming was a watershed moment in the history of the human race. But the tableau typical of post-industrial society is so highly romanticised that we miss out on the chequered history and rich symbolism of the Nativity. Millions attend Mass on the world’s most prominent holiday, only to top it up with a secular, not to say raucous, celebration. Here the divine protagonist is easily forgotten and Santa the antagonist highlighted. In short, we forget the reason for the season.

With half a century of Christmases behind me, I feel more and more concerned about our collective failure to grasp the mystery of the joyous occasion. How I yearn to approach the manger with the simple heart of the proverbial shepherd and the sublime mind of the famed Magi!

(Herald, 23.12.2019)

The Last Things – First!

“In all thy works remember thy last end, and thou shalt never sin.”

(Ecclesiasticus, 7:40)

When we lose a loved one, our hearts ache and a great unease pains our sense. Wrestle how we might, we come to accept the reality only after we have decided, like Keats in ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, that to them ‘now more than ever seem[ed] it rich to die, to cease upon the midnight with no pain’. Eventually, we gratefully recognize that history had been unfolding before our very eyes through God’s infinite wisdom, mercy and goodness. Peace descends on us and the former unease turns into a wish simply to remain spiritually united with the departed soul.

Taking in the inexorable mystery of death – and, specifically, the passing away of a near and dear one – is an important milestone in our lives. Helen Keller once said apropos the proper use of the physical senses: “Sometimes I have thought it would be an excellent rule to live each day as if we should die tomorrow. Such an attitude would emphasize sharply the values of life. We should live each day with a gentleness, a vigour, and a keenness of appreciation which are often lost when time stretches before us in the constant panorama of more days and months and years to come. There are those, of course, who would adopt the Epicurean motto of ‘Eat, drink, and be merry’, but most people would be chastened by the certainty of impending death.”

Many of us would also wish to gaze beyond our earthly life, seeking to understand what is to become of us after death. And should we wonder why we are born at all if we are to die some day, we will realize that there is more to life than just this earth. It requires only that leap of faith to see that, like matter, the soul changes its form but is never destroyed; that life returns to where it has come from: the bosom of the Lord!

Communion of Saints

Catholic doctrine has comforting answers to the eternal questions of Life and Death: it would be of immense spiritual profit if we learnt them in time, so that whether or not we gain this whole, wide world, we might be poised to earn the next!

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) teaches us that, living or dead, when in a state of grace we live in Christ as ‘saints’; that there is the church of heaven and of earth, where the saints live in communion with each other and with God, much in the manner of the Triune God!

The CCC emphatically says, “What is the Church if not the assembly of all the saints? The communion of saints is the Church,”[1] and goes on to explain that the term has two closely-linked meanings: communion in holy things and in holy persons.[2]

The communion in holy things or spiritual goods comprises (1) the faith received from the apostles and kept alive through prayer; (2) the sacraments, most importantly the Eucharist; (3) the charisms, or graces that the Holy Spirit distributes among the faithful for building up of the Church; (4) our possessions, which are, really speaking, the Lord’s goods under our stewardship; and, finally, (5) love, whereby if one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honoured, all rejoice together.

The communion in holy persons refers to the life that the saints of heaven and earth live in common. While some of Christ’s disciples are still pilgrims on earth, others have died and are being purified; yet others are already in glory, contemplating God in full light. The exchange of spiritual goods, while it helps the departed to attain the Beatific Vision, also makes their intercession for us effective. Finally, being more closely united to Christ, they fix the whole Church more firmly in holiness.

In his book True Spiritualism, Fr. C. M. de Heredia, S.J., calls the Communion of Saints “a Divine Corporation, a great communism in which all the saints in heaven and all the souls in purgatory and all the children of the Church on earth form one vast family, of which Christ is the head, and participate in all spiritual goods that are in common.” The early Christians in Jerusalem “had but one heart and soul; neither did any one of them say that, of the things which he possessed, anything was his own; but all things were common to them. [...] And those who had houses and lands sold them and laid the price at the feet of the Apostles who distributed them to every one according to their needs.” (Acts 4: 32, 34) The Communion of Saints is this same idea “raised to the heavenly sphere, embracing both planes of existence, enveloping the finite world and entering into the infinite, the idea that makes common property not so much of earthly as spiritual goods.”[3]

Vocation of the Church

The CCC says, “If we continue to love one another and to join in praising the Most Holy Trinity – all of us who are sons of God and form one family in Christ – we will be faithful to the deepest vocation of the Church.”[4]

What is the deepest vocation of the members of the Church? It is to know God, love Him and serve Him. So it behoves us to learn how to do all these things! We should (re-)arrange our worldly priorities so that God becomes the centre of our lives and is forever praised in all that we do. On balance, this is what holds out the eternal reward after our life in this valley of tears!

“It has been alleged oftentimes,” says De Heredia, “that the Church has taught that in this world there is nothing but misery, and that she is not for this life but for the next. Well do we know how erroneous that is! As the soul is greater than the body even in this life, so does it follow that the pleasures of that soul are greater than the pleasures of the body. It is the Church which teaches us how to be happiest in this life and happiest in the next. The philosophy that reduces the world’s playthings to their proper perspective and makes man at once great in the accomplishments of earth and at the same time divinely indifferent to them is hers. [….] No hedonist, no aesthete, however rapturous his pagan worship of beauty, can equal the Catholic even in pursuit of earthly happiness.

“But immeasurably beyond these sources of joy, the Catholic has his firm hope in the everlasting happiness of heaven. He has his trust in a God who loved man so much that He came to earth and died for him. The light of Paradise is in his eyes. The beauty of God illuminates his soul. The caresses of his Heavenly Father are on him. And he has his belief in the power and companionship of the Communion of Saints.”[5]

Last Things First!

The communion of saints is a marvellous reality.[6] But this can be fully appreciated only against the background of eschatology, the teaching about the ‘Four Last Things’: death, judgement, heaven and hell. These apply to the individual, while the resurrection of the bodies and the final judgement at the second coming of Christ are for the human race as a whole.

Knowledge about the ‘Last Things’ is best not left for the last moment (as St Francis of Assisi says, “We shall die sooner than we expect”). We are duty-bound to see that the ‘communion of saints’, ‘the forgiveness of sins’, ‘the resurrection of the body’, and ‘the life everlasting’ from the ‘I Believe’ are not mere words but operating realities! We must understand that the ‘hour of death’ that the ‘Hail Mary’ reminds us of is not just another moment in a distant, even undefined, future but could come sooner than later! And we who recite the ‘Our Father’ and assist at Mass would do well to learn what is meant by the ‘Kingdom’ and ‘Eternal Life’! Such fundamentals of our faith have to be transferred from the tomes of theology to the homes of everybody – meditated upon, discussed, internalized, and acknowledged in our daily life. Or even a prayer, like the following one to St Joseph, composed by none other than Pope Pius X, points to the true worth of those concepts.

O Glorious St. Joseph, a model for all who are devoted to labour, obtain for me the grace to work in a spirit of penance, for expiation of my ma ny sins; to work conscientiously, putting the call of duty above my inclinations; to work in recollection and joy, deeming it an honour to employ and develop through labour the gifts received from God; to work with order, peace, moderation, and patience, never shrinking out of weariness and trials; to work, above all, with purity of intention and with self-detachment, having ever before my eyes death and the account that I will have to render of time lost, talents wasted, good omitted, and vain complacency in success, so baneful to God’s work.

ny sins; to work conscientiously, putting the call of duty above my inclinations; to work in recollection and joy, deeming it an honour to employ and develop through labour the gifts received from God; to work with order, peace, moderation, and patience, never shrinking out of weariness and trials; to work, above all, with purity of intention and with self-detachment, having ever before my eyes death and the account that I will have to render of time lost, talents wasted, good omitted, and vain complacency in success, so baneful to God’s work.

All for Jesus, all through Mary; all after thy example, O Patriarch St Joseph! This will be my watchword in life and in death. Amen.

This is eschatology made simple... eschatology in action! We are gently reminded that this world and the next are seamlessly woven into one whole; that what we do now – and how we live and work – determines our later fate.

It is easy to see that the Last Things are relevant not only to the afterlife but also immensely so to our present life. By letting us realize our final end, they bring about the required change in our worldview. They determine our dreams and aspirations as well as our response to earthly trials and temptations; they shape the nature of our hope and our way of life. They teach us why it is natural to seek first the kingdom of God and its justice; and how to be in the world and not of it.

It is surprising that we Catholics seldom talk actively about the Last Things. It is as though a conspiracy of silence is militating against our understanding them fully, thus even giving Eternal Life a semblance of fiction. Alas, we fail to realize that, by ignoring this real important aspect of our Christian existence, we let pessimism and despair cloud our consciousness. This is truly asphyxiating for the Catholic soul.

On the other hand, the greater our engagement with the Last Things the better it is for God’s people. A culture of hope and consolation is fostered, lending that much-needed supernatural quality to our being. We begin to live an integrated Catholic life. The communion of saints in heaven and earth is made active, and the Kingdom comes.... All good enough reasons to put the Last Things first!

(Renovação/Renewal, Goa, 16-31 August 2011)

[1] CCC 946

[2] The communion of saints is not linked to ‘spiritism’ (contact with the dead), which is disallowed by the Church.

[3] C. M. de Heredia, True Spiritualism, P. J. Kenedy & Sons, New York, 1924, p. 9-10

[4] CCC 959

[5] Op. cit., p. 28-29

[6] Whoever doubts this may refer to a simple little book, Read me or Rue it, by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P., TAN Books, 1992 (First published in 1936, with approval from His Eminence the Cardinal Patriarch of Lisbon): It carries captivating true stories about the Poor Souls in Purgatory.

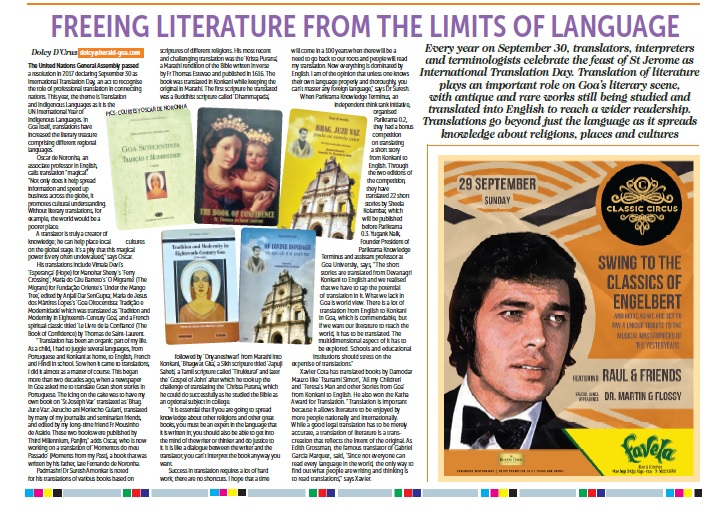

A Life in Translation

Quasi-Memoir-1

I was clueless as to 30 September, International Translation Day, instituted two years ago. I got the lowdown from that enterprising, Herald journalist Dolcy D’Cruz: for the purpose of a feature to mark the occasion, she'd sought to know what translation meant to me and how I went about my activity.

‘Translation is a magical thing,’ I said to her, almost instinctively. ‘Not only does it help spread information and speed up business across the globe, it promotes cultural understanding.’

At the back of my mind were Tolstoy and Dostoevksy, Verne and Dumas, Anderson and Grimm, authors whose native languages I didn’t know. And I shed a tear for those who had to depend on renderings of Shakespeare, Dickens and Twain, and why not, Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie and P. G. Wodehouse. I was lucky to read them all in the original, as I was, when it came to my father’s recommendation of a Portuguese staple diet: Júlio Dinis, Garrett, Camilo, Eça, Ramalho, Aquilino, for a novice; and my additions: Pessoa, Torga, Namora, Agustina, Lobo Antunes, and Saramago (with a pinch of salt).

Literary translations have made the world richer. And it’s not literature alone that has depended on translations; even the most disparate subjects like history, medicine and everything in between have benefited from them. If in the early twentieth century, seminarians in our archdiocese had to depend on Latin texts, it wasn’t only because that’s the official language of the Church; there were no translations available in the vernacular!

Even more picturesque was my doctor aunt’s story about the use of French manuals at the Goa medical school, as late as the 1950s: students had soon cultivated the art of reading them aloud in twos or threes, and straight in Portuguese. That was magic!

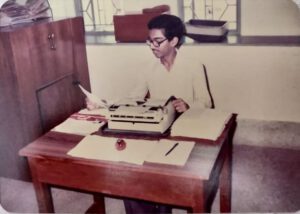

Early days

As aural memories came gushing, I began to realize that translation had indeed been an organic part of my life. As a child juggling several languages, from Portuguese and Konkani at home, to English, French and Hindi at school, oral translations happened almost as a matter of course. I would reproduce in Portuguese information that I’d received in English, and vice-versa. Mixing of lingos and literal translations were a big no-no, whereas idiomatic language was warmly encouraged.

Yet, translation per se was never the main concern; the accent was on reading good literature and relishing good conversation; it was about having a dictionary at hand and looking up the meaning of an unfamiliar word; it was about finding le mot juste. It was no cakewalk but, looking back, the long walk was so worth it. And a job well accomplished always translated into joy.

After my father’s remark, ‘Languages are an asset; master them while you’re young,’ the next best thing that stuck in my head was Bacon’s famous quote: ‘Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.’ This was like a command from on high. Or for that matter, F. J. Sheed’s dictum that ‘… minds feed on minds, you cannot nourish your mind with a chop,’ struck me as very sensible.

After handling English texts, ‘ex officio’, on school days, I would spend bits of late Sunday mornings decoding Portuguese texts under my father’s tutelage. By the end of high school, I had begun devoting an hour or so to transcribing All India Radio afternoon news bulletins for O Heraldo. And why? Now it just seems so funny: I’d found this arrangement vital since Goa’s first daily, which was on its last legs, no longer subscribed to news agencies and was starving for news. I also thought it would reassure my father who, after retiring prematurely, lent a hand at the paper – for the love of the Portuguese language and practically for free.

In the public domain

That happened to be my first stint with translation outside the domestic sphere. I didn’t think any good would come out of all that. But, three years later (1983), when I least expected it – I was in the first year of college – the then Jesuit priest Teotonio R. de Souza invited me to work as a research assistant at the newly established Xavier Centre of Historical Research of which he was the director. My task was to create summaries in English of the Mhamai Kamat papers written in Portuguese and French. I was also pleasantly surprised that he’d entrusted me two of his research papers for translation. That we argued playfully about his views is quite another matter entirely!

After my MA at the University of Bombay (1985-87) and a language and culture course at the Universidade de Lisboa (1988), I had a short stint as a lecturer in Portuguese at Dhempe College, Panjim, chiefly, to replace my father who was down with malaria. After a few months, I hesitantly took up an interpreter’s job at the Embassy of Brazil, lured by the national capital. On arriving there, however, I was stunned to see that I would be assisting an eighty year old: Pylades Prata Tibery, a Brazilian national of Greek and Italian ancestry, introduced himself as a ‘juiz de gado’ (cattle judge).

Tibery and I crisscrossed the subcontinent, by road and rail, trailing the Nellore buffalo – a breed that, according to the garrulous old man, Brazil had imported from India in the early twentieth century. Our activity was interspersed with a generous exchange of notes on European and Brazilian Portuguese. While the English of his school days was amusing, even more so were his colourful descriptions of ‘convivial society’ expressed in his native Brazilian.

Well, I could hardly be buffaloed by a more outlandish task even if handsomely paid, as indeed I was. It marked the beginning and the end of my honeymoon with translation/interpretation as a full-time job... On my return to Goa, I took up teaching as a career. After the initial hiccups, I found fulfilment in interpreting my students’ thoughts and feelings, and translating their ignorance into knowledge, their anxieties into hope, and their ambitions into reality! Translating and interpreting could now only be side gigs, mostly to oblige friends and family. For instance, I liaised at a couple of wine festivals and carried out humdrum legal translations, among other things. Even these I could no longer endure when I finally had my eyes set on translating literary, historical and spiritual texts. That would surely be a balm to my spirits.

Literary translation

Sometime in 1995, a brief encounter with Editor Arun Sinha of The Navhind Times provided that go. Keen on setting up a literary page to step up his paper’s Sunday magazine, ‘Panorama’, he suggested I work on Goan short stories written in Portuguese. I did produce quite a few translations, but alas, inevitable changes on the home front constrained me to discontinue the series.

But in spite of everything, mine has continued to be a life in translation, of which the Herald article gives a glimpse (see the link below).

(To be continued)

Aquela doce palavra ‘Fátima’…

Era eu ainda menino quando ouvi da boca da Avó Leonor a história de Nossa Senhora de Fátima. Nessa altura, foi o enredo, ou seja, a descrição pastoral, que deveras me impressionou; e também o facto de a Mãe de Jesus ter pedido a recitação diária do Terço e que os maus se tornassem bons para poderem alcançar o Céu.

De vez em quan do ia lendo umas publicações sobre Fátima que tínhamos na nossa biblioteca em casa – uma delas, Fátima, Altar do Mundo, de João Ameal. Atraía-me esse fantástico subtítulo – “Altar do Mundo” – bem como as lindas fotografias a preto e branco.

do ia lendo umas publicações sobre Fátima que tínhamos na nossa biblioteca em casa – uma delas, Fátima, Altar do Mundo, de João Ameal. Atraía-me esse fantástico subtítulo – “Altar do Mundo” – bem como as lindas fotografias a preto e branco.

Uma outra publicação que costumava folhear era o Souvenir publicado em Goa por ocasião do cinquentenário das Aparições de Fátima (1967). Tinha artigos da autoria de escritores goeses – inclusive hindus – escritos em português, inglês e concani.

Nesse opúsculo vi pela primeira vez uma foto memorável de que falava meu pai: a Imagem da Virgem Peregrina a atravessar o rio Mandovi, a caminho da Velha Cidade, no dorso dum gasolina que se apresentava em forma dum grande cisne branco fabricado por artistas goeses. E, desembarcando junto ao Arco dos Vice-reis, essa imagem seguiu em magno cortejo até o local onde iriam ser rezadas, simultaneamente, 153 missas, a representar as Ave-Marias do Rosário! Que imponente cena! Nessa visita que se realizou de 29 de Novembro a 12 de Dezembro de 1949 a Imagem percorreu o território de Goa.

Daí a vinte e cinco anos, ou seja, em 1974, foi anunciada uma outra visita da Imagem. Desta vez, houve grande polémica na imprensa local. Não me lembro qual foi o argumento principal; sei só que se tratava de um debate entre duas gerações de clérigos goeses. Porém, quando chegou a Imagem houve grande concorrência dos fiéis. Com os meus 9 anos de idade fiquei com esta dúvida: como é que podia haver duas opiniões sobre a visita da Mãe de Jesus?!

9 anos de idade fiquei com esta dúvida: como é que podia haver duas opiniões sobre a visita da Mãe de Jesus?!

Entretanto, constituíam já uma tradição consagrada as chamadas procissões de velas, que se realizavam na capital, em Maio e Outubro. Era entoado um e outro cântico em português. Embora parecesse um simples ritual herdado a Portugal, para mim era esse país era o “povo escolhido” dos tempos modernos (já que o antigo não se portara bem!)

Também meu pai, de saudosa memória, sem nunca se esquecer do sentido mais amplo da mensagem de Fátima, parecia frisar o lado português do grande acontecimento que se tinha dado em Fátima, exprimia esse sentir no seu poema “Portugal e Fátima”, que veio publicado n’O Alcoa, de Alcobaça:

Portugal e Fátima Primeira Grande Guerra… Só sangueira, Luto e desolação por toda a Terra!… Angustiada, aparece, pois, na Serra A nossa Virgem Mãe numa azinheira (Cova da Iria); e diz com emoção que vão cessar as hostilidades (é a bonança a seguir a tempestades). Anima o mundo à sua reconstrução. E a Portugal diz:- Eis que te darei Dois jovens que guiarão nessa peleja: Um, que traz veste da cor de cereja; E o outro, de quem muito justamente d’rei: Tem muito sal na fala e afasta o azar.– E assim foi, pois: seguira-se uma era De real prosperidade e paz sincera, Por cerca de meio séc’lo, sem armar… Tal como não há rosas sem espinhos, Não podem faltar cravos nem cravinhos Que perturbem a vida nacional Neste sempre querido Portugal! Mas, haja o que houver, disse a Senhora de Fátima que é sua protectora nata:- “Meu Coração, pois, triunfará”. E, quem acreditar não poderá?

Em 1987, tive o ensejo de visitar Portugal. Fui a Fátima, onde vi peregrinos de joelhos; e uns a cantar e outros a chorar… Emocionante! Impressionou-me bem o recinto do Santuário e a vasta praça pública mas fiquei triste por ver uma intensa actividade comercial ao redor!

Entretanto, fui reflectindo sobre o facto de Fátima não ser um mero sítio ou história: os três pastorinhos eram afinal personagens ímpares no palco internacional e arautos da mensagem divina que merecia bem ser escutada pelo Planeta Terra.

Depois que voltei a Goa, em 1988, estive em contacto com a Sociedade Brasileira de Defesa da Tradição, Família e Propriedade, que tinha acabado de publicar o livro intitulado As Aparições e a Mensagem de Fátima nos manuscritos da Irmã Lúcia, de autoria de António Augusto Borelli Machado. Este livro teve depois uma edição inglesa, feita em  Goa. Eram os anos do desmoronamento do Império Soviético e outros acontecimentos apocalípticos cuja explicação completa se encontrava na mensagem de Fátima.

Goa. Eram os anos do desmoronamento do Império Soviético e outros acontecimentos apocalípticos cuja explicação completa se encontrava na mensagem de Fátima.

Tornei-me ainda mais devoto da Senhora de Fátima. Mas enquanto eu fitava a sua dimensão universal, Nossa Senhora olhava, com carinho maternal, para a minha vida pessoal: ajustar-me-ia com a Isabel, nascida em 13 de Maio, e levando por isso os nomes Maria e Fátima!

Cinco anos depois, casámos nesse dia. No fim da missa do casamento a Isabel fez (e eu renovei) a Consagração a Nossa Senhora segundo o método de S. Luís Maria Grignion de Montfort!

Uma e outra pessoa, católica mas também supersticiosa, nos tinha recomendado não casar no dia 13, sexta-feira. Mas pusemo-nos, a Isabel e eu, incondicionalmente a favor dessa data.

Um ano e meio depois sucedeu-nos algo que essas pessoas devem ter tomado como plena justificação dos seus palpites. Nascia-nos um menino – Fernando – que, pouco depois, começou a ter problemas bastantes graves! Pensámos, porém, que Deus podia mandar uma prova dessas a qualquer pessoa; com que direito poderíamos ser uma excepção? O importante era Deus estar connosco, como realmente esteve, e continua a estar!

No hospital, onde passámos os primeiros três meses da vida do Fernando, cheguei a ler, com grande consolação e deleite espiritual, o livro Fatima, de William Thomas Walsh. Foi um dos poucos livros que pude ler durante o período da crise por que passámos, a Isabel e eu, junto com a família inteira.

Tomámos tudo isso como uma prova da nossa fé; e tínhamos já recebido a resposta a todas as dúvidas suscitadas no interim: era a Senhora de Fátima que nos vinha ajudar a encarar de forma sobrenatural a vida, esta nossa peregrinação na terra.

Fernando não se curou completamente mas sucedeu algo que a medicina não achava possível... Está estável, com uma alegria de viver, e é devoto de Nossa Senhora!

Uns anos depois nasceu-nos o Emmanuel, que leva o nome do Esposo de Maria Santíssima: José! E quando nasceu a Vera, uns dias após a morte da Vidente Lúcia, foi ela baptizada também com esse nome de luz.

Eis algumas facetas da nossa relação com a Mãe Celeste… E eis porque ainda nos fala ao coração aquela doce palavra Fátima.

(Em conversa com Cristina Arouca, em 2012)

(Em conversa com Cristina Arouca, em 2012)

Ver:

Fátima no Mundo, de Manuel Arouca e Cristina Arouca Editora Ofício do Livro, 2016) https://www.amazon.com/F%C3%A1tima-Mundo-Portuguese-Manuel-Arouca/dp/9897414320) Fátima e o Mundo, documentário, Ep. 611, Dezembro de 2016: Fátima e a Ásia e a Oceânia. https://www.rtp.pt/play/p2909/e263645/fatima-e-o-mundo

The Two Abbés

Who in Goa hasn’t seen that striking bronze figure of a tall man in a flowing robe, with a lady tumbling down at his feet? Sculpted by Ramachondra Panduronga Kamat and erected next to the Adil Shah Palace, the statue is now in its seventy-fifth year. It was a tardy tribute to a nineteenth-century Goan celebrity – Abade Faria – considered the ‘father of modern hypnotism’.

For every passer-by that admires that lofty monument, there are thousands the world over who would be reminded of a literary character of the same name: Abbé Faria from Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte-Cristo. This adventure novel was published a century before that statue was put up in Panjim.

Are the Abade and the Abbé one and the same person? Faria is a surname; abade and abbé mean ‘abbot’ in Portuguese and French, respectively. The historical Faria only served as a literary inspiration for the celebrated French writer. Some parallels are obvious between the two figures but not all of them do justice to the flesh and blood Faria.

The real Faria was born José Custódio de Faria, in Goa, then Portuguese India. After eight years of priestly studies and a doctorate in Rome, he lived in Lisbon for the same number of years. Finally, he settled down in Paris, where he spent over thirty years, with a year or so in Marseilles and Nimes. In France he was referred to as Abbé Faria.

Dumas’ learned Abbé is a linguist, philosopher, and a strong-willed man. Our Abbé was proficient in philosophy, theology, history, and he intuitively discovered hypnotism; he knew Konkani, Portuguese, Latin and French; and was a resolute man. The physical attributes of the two are similar, except for their height.

The novel is set in the bay of Marseilles, where the fictional Abbé is imprisoned; the real Abbé worked in that port town as a professor of philosophy, in 1811. The former is nicknamed ‘Mad Monk’ by the prison staff; quite intriguingly, our Abbé too was derided by doctors, writers and fellow pastors for his ideas on hypnotism, in Paris (1813-19). Similarly, the Abbé’s description of lodging and boarding in jail could well be a mirror image of the real Faria’s living conditions at the Orties convent. Dumas’ inspector of prisons would be the equivalent of an actor, Potier, who lampooned our Abbé in Jules Verne’s fateful play, Magnétismomanie.

Coming now to Abbé Faria’s tunnelling for three long years: it could be interpreted as the real Abbé’s quest for ideas and materials in support of his theory of sommeil lucide (lucid sleep). When they died of fulminating apoplexy, in their sixties, both characters had their books still unpublished. The real Faria’s book De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man) came out posthumously; the remaining three volumes were untraceable, much like the jailed Abbé’s book that was never found.

While Dumas’ Abbé is an Italian, born in Rome; the Goan Abbé was born in the ‘Rome of the East’. The hero, Dantès, once journeyed to India, whereas José travelled from India to Europe, and never went back to his homeland. Interestingly, the fathers of both have important roles in their sons’ lives. Could Dumas have known that José’s father in Lisbon was under house arrest for his nativist ideas, and that many of the conspirators of 1787 in Goa met with a fate worse than death? Apparently, José’s father and Dumas himself were both republicans at heart.

Finally, the treasure that the Abbé highlights in the novel could be a pointer to the treasure that the historical Abbé Faria endowed us with, in the form of hypnotism: this has long been an invaluable aid to the physical and mental well being of humankind.

It is sad that Faria fans find it hard to separate fact from fiction: shrouded as he is in deep mystery, the real Faria comes out largely disfigured. But given that historians and medicos took no steps to fix that shortcoming, how can one fault Dumas for taking artistic licence? After all, the man who died, disdained and forgotten, on 20 September 1819, was kept alive in the pages of The Count of Monte-Cristo. It now behoves us to put the historical Faria on a pedestal much higher than the one on which he is placed in Panjim’s main square.

Three Cheers to Abade Faria!

Three episodes among many others in the life of Abade Faria call for resounding cheers. The first is that he grew up under very unusual and trying circumstances, yet came out a champion. Born Joseph Custódio de Faria, in the year 1756, his parents Caetano Vitorino de Faria, who hailed from Colvale, and Rosa Maria de Souza, from Candolim, separated canonically within ten years of marriage. Thereafter, the husband took holy orders in the then seminary of Chorão; the wife joined St Monica, Asia’s largest nunnery, as a lay sister of the white veil. And the three were never together again as a family.

In such a situation, José Custódio came across as an oddity. He must have had a lot of explaining to do wherever he went. In those days, how was it to be raised by a single parent? This aspect of Goa’s forgotten celebrity hasn’t received attention from historians and psychologists. At fifteen, José Custódio travelled with his dad to Lisbon, en route to Rome. Priestly studies awaited him at the Pontifical Urban University. And both father and son secured doctorates in the Eternal City. The young man left no stone unturned in his solitary yet creative life.

The second reason to celebrate Abade Faria is that he sailed uncharted seas. He spent eight years (1780-88) with his nativist father, who was considered the ‘patriarch and patron’ of the Goan community in Lisbon. Then, Faria Jr. went to France, in search of greener pastures. His arrival coincided with the political turmoil of the Revolution, when royalists and clergy alike were getting a raw deal. He bided his time until 1795 when he placed himself at the head of a revolutionary battalion and marched against the National Convention. The five-member Directory that seized power ended the Reign of Terror; they also relaxed the measures that had been instituted against exiled priests and monarchists. Fr. José Custódio de Faria thus had the curious distinction of being the one and only Goan participant in the French Revolution.

By now, the Goan cleric was ‘Abbé Faria’ to everyone. ‘Abbé’ is French for priest or abbot; in Portuguese they wrongly called him ‘Abade’ (abbot), which he was not! As though compensating for that mistranslation, the father’s clarion call in Konkani was properly captured by bystanders: “Hi soglli bhaji… Kator re bhaji!” – ‘Strawheads all, chop them off!’ And that’s how a concerned father rescued his preacher son awestruck in the pulpit, before the Queen and the nobility gathered in the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

There is no hard evidence to support that claim but the senior Faria’s alleged cry has long been part of the Goan lore. I have a hunch that this set the ball rolling for an unprecedented career for the junior Faria. That legendary transformation brought about by half a dozen, suggestive words uttered by a devoted father must have rung in the son’s ears for a long time to come. It may be facile to connect the episode to the theory of hypnotism by suggestion that Abade Faria pioneered, but here it goes nonetheless!

After a stint as professor of philosophy in the port city of Marseilles in 1811, the Abbé finally settled down in Paris where he gave sessions of hypnotism. He died there in 1819, but not before rejecting Mesmer’s animal magnetism and expounding a new theory of hypnotism. Faria put the subject on a sound footing, coining the term sommeil lucide (lucid sleep). He dwelt on this at length in his magnum opus, titled De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme, that is, ‘Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man’, which was published posthumously. And it is a pity that the remaining three volumes never saw the light of day.

Abade Faria made a seminal contribution to the field of science. Hypnosis soon became a vital aid to physiology and medicine, and is still so to psychiatry, psychoanalysis and surgery. No doubt, the discoverer was initially derided by doctors, writers, and pastors, but the scientist came out victorious. Today, he is universally regarded as the ‘father of modern hypnotism’.

Three cheers, then, to the greatest untrained Goan scientist of all times, on his 200th death anniversary today!

(The Goan, 20 September 2019)

http://epaper.thegoan.net/2335415/The-Goan-Everyday/The-Goan-Everyday#page/10/1

When I met Abade Faria...

I lived next door to Abade Faria for thirty years. As a child, I remember asking my father what that name meant. Keen on passing on informatio n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

Abade Faria is that very striking statue in the heart of Panjim. I couldn’t have met the man himself: José Custódio de Faria was born in 1756, at his mother’s house in Candolim. His father was from a less known village, Colvale. As I came of age, I learnt that he was the son of a priest and a nun… Hold on! They were ‘normal’ people, Caetano Vitorino de Faria and Rosa Maria de Souza, who got married, had a child, and then broke up. The father took holy orders at the then Chorão seminary while the mother joined St Monica, Asia’s largest nunnery, at Old Goa.

The father-son duo then travelled to Lisbon, and onward to Rome, where Faria Jr. was ordained a priest and the father-son duo did their doctorates in theology. On their return to Lisbon, the father was left harbouring nativist ideas; the son, seeking a safe harbour, proceeded to France, in 1788.

That’s how the name ‘Abbé Faria’ makes sense. The French word for ‘priest’ is still in vogue in the English-speaking w orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

In 1988, as I arrived in France, Faria’s poignant story raced through my mind like a film. It was exactly two centuries since the only Goan who participated in the Revolution had stepped into Paris. Alas, I found no trace of his addresses in that magnificent global city. So I was hopeful about seeing the Abbé next in the luminous port city of Marseilles. My joy knew no bounds when I finally sighted a street named after him.

There I was quizzing a few pedestrians on that sleepy thoroughfare. When the very first speaker confessed his ignorance, I was crestf allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’

allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’ s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

My third and final encounter was most memorable. When I fired my standard question – ‘Who is this Abbé Faria?’ – the man playfully shot back at me, saying, ‘He was an Indian – like you!’ And with a smile playing on his lips, he vanished into thin air, while I was stuck in a hypnotic state!

Back in Goa, my interest in Faria redoubled. One fine afternoon, very significantly, the fourth of July, my fiancée came along to see my friend Abade Faria in Colvale. Just locating his family estate in that northernmost village of Bardez took us longer than getting there all the way from Panjim. It felt as though we were searching for something in pitch darkness, no flashlights in hand, when really it was broad daylight… What an exploration indeed!

Renowned historian J. N. da Fonseca, who purchased the Faria estate in the nineteenth century, built a house there, possibly on the ruins of the hypnotiser’s family house. Only the private chapel was spared.

When I was working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m

working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

So, you see, it was great getting to know Abade Faria – my civic duty, to say the least. You too can trail him now. Begin today, on his 200th death anniversary.

(Herald Café, 20 September 2019, p. 1)

https://www.heraldgoa.in/Cafe/WHEN-I-MET-ABADE-FARIA%E2%80%A6/151383