When I met Abade Faria...

I lived next door to Abade Faria for thirty years. As a child, I remember asking my father what that name meant. Keen on passing on informatio n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

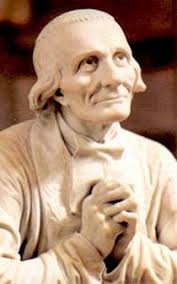

Abade Faria is that very striking statue in the heart of Panjim. I couldn’t have met the man himself: José Custódio de Faria was born in 1756, at his mother’s house in Candolim. His father was from a less known village, Colvale. As I came of age, I learnt that he was the son of a priest and a nun… Hold on! They were ‘normal’ people, Caetano Vitorino de Faria and Rosa Maria de Souza, who got married, had a child, and then broke up. The father took holy orders at the then Chorão seminary while the mother joined St Monica, Asia’s largest nunnery, at Old Goa.

The father-son duo then travelled to Lisbon, and onward to Rome, where Faria Jr. was ordained a priest and the father-son duo did their doctorates in theology. On their return to Lisbon, the father was left harbouring nativist ideas; the son, seeking a safe harbour, proceeded to France, in 1788.

That’s how the name ‘Abbé Faria’ makes sense. The French word for ‘priest’ is still in vogue in the English-speaking w orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

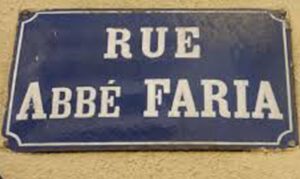

In 1988, as I arrived in France, Faria’s poignant story raced through my mind like a film. It was exactly two centuries since the only Goan who participated in the Revolution had stepped into Paris. Alas, I found no trace of his addresses in that magnificent global city. So I was hopeful about seeing the Abbé next in the luminous port city of Marseilles. My joy knew no bounds when I finally sighted a street named after him.

There I was quizzing a few pedestrians on that sleepy thoroughfare. When the very first speaker confessed his ignorance, I was crestf allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’

allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’ s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

My third and final encounter was most memorable. When I fired my standard question – ‘Who is this Abbé Faria?’ – the man playfully shot back at me, saying, ‘He was an Indian – like you!’ And with a smile playing on his lips, he vanished into thin air, while I was stuck in a hypnotic state!

Back in Goa, my interest in Faria redoubled. One fine afternoon, very significantly, the fourth of July, my fiancée came along to see my friend Abade Faria in Colvale. Just locating his family estate in that northernmost village of Bardez took us longer than getting there all the way from Panjim. It felt as though we were searching for something in pitch darkness, no flashlights in hand, when really it was broad daylight… What an exploration indeed!

Renowned historian J. N. da Fonseca, who purchased the Faria estate in the nineteenth century, built a house there, possibly on the ruins of the hypnotiser’s family house. Only the private chapel was spared.

When I was working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m

working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

So, you see, it was great getting to know Abade Faria – my civic duty, to say the least. You too can trail him now. Begin today, on his 200th death anniversary.

(Herald Café, 20 September 2019, p. 1)

https://www.heraldgoa.in/Cafe/WHEN-I-MET-ABADE-FARIA%E2%80%A6/151383

Why I grieve for Brazil

Who could remain unruffled in the face of the fires raging in the Amazon? My heart went out to Brazil as I watched that footage on television. I was equally distressed last year, when flames consumed that country’s oldest and most important historical and scientific museum.

A lot more connects me as a Goan to the vibrant South American nation, a cultural melting pot many times larger than my land.

The Goan connection

As a Goan, I grieve at the way things turned out for the Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, on that fateful night of 2 September 2018. Founded in 1818, by king Dom João VI of Portugal, the museum housed precious collections of natural history and science built up over a couple of centuries. The edifice was earlier the home of the Portuguese royal family in exile (1808-1821), and thus had a close bond with Goa. Even after the Brazilian imperial family took over (1822-1889) Goa continued to enjoy relations with that country.

With the monarchy gone, the old royal museum moved into the palace. When I saw the blaze, I had a flashback of that king who had settled in his American colony following the Napoleonic invasions; of his young son, Dom Pedro IV (1798-1834), whose heart bled for Portugal; and, finally, of an eminent Goan, Bernardo Peres da Silva (1775-1844), who, as a friend of the latter, must have stepped into the palace several times to discuss the sad state of affairs in their tiny nation across the Atlantic.

Peres da Silva belonged to the first batch of Goa’s deputies to the Portuguese Parliament. On his first two stints, he couldn’t take his seat for the Absolutists had dissolved the Cortes. In 1822, a circuitous trip via Mozambique and Rio de Janeiro, by force of circumstances, delayed his arrival in Lisbon. In 1827, he went on self-imposed exile to Plymouth (England) and sailed thence to Rio. He returned to Portugal only after Dom Pedro IV had reclaimed the crown from his younger brother Dom Miguel.

In Diálogo entre um doutor em philosophia e um portuguez da Índia (Rio de Janeiro: Tip. Nacional, 1832), the first-ever publication by a Goan in Brazil, Peres da Silva espoused the Liberal cause. He dedicated that political essay to the youth of Portuguese India. He was rewarded for his loyalty by being appointed Prefeito dos Estados da Índia. The response to his mixed bag of reforms in Goa was altogether another matter. A coup ousted the colony’s first and last native civil governor, who was indeed a unique gift from the Emperor of Brazil and Regent of Portugal, Dom Pedro IV, to Portuguese India.

The human connection

The human connection

Well, a lot more connects me as a Goan to the vibrant South American nation, a cultural melting pot many times larger than my land. However, given that the house is presently on fire, I’d restrict myself to ecological parallels. For instance, the Western Ghats are to Goa what the Amazon is to Brazil: rainforests both, which together with their global counterparts fulfil forty per cent of the earth’s oxygen needs.

It is, then, as a human that I grieve for the inferno that set off in the Amazon on 23 August 2019. Representing over half of the planet's rainforests, it is the world’s largest and most bio-diverse tract of tropical jungle, with an estimated 390 billion individual trees divided into 16,000 species. The Amazon basin has an area of 7,000,000 km2, of which eighty per cent (5,500,000 km2) is wooded. Although its name is synonymous with Brazil, the Amazon does not belong to Brazil alone. It is perhaps less known that, while 58.4% of the rainforests are within the Brazilian borders, the rest is shared by eight countries: Peru (12.8%), Bolivia (7.7%), Colombia (7.1%), Venezuela (6.1%), Guyana (3.1%), Suriname (2.5%), French Guyana (1.4%), and Ecuador (1%).

Out of those nine, only French Guyana is not an independent state but an overseas department and region of France. Bordering Brazil to the east and Suriname to the west, it is the only territory of the mainland Americas fully integrated in a European country. Hence, the Amazon’s well-being is the duty of France too. But alas, wildfires apart, deforestation for farming is one of the most serious threats to the woodlands – and, what’s more, all nine jurisdictions are guilty of the crime.

When I grieve for Brazil – the world in miniature – I also grieve for the world as a whole.

If so, why is Brazil alone under the scanner? Its main accuser, France, is at fault, too – in fact in Europe and America. It didn’t do enough for the Notre-Dame, one of the greatest specimens of world cultural heritage: the cathedral lost its roof, spires and more. Yet, the haughty French are shouting it from the rooftops that Brazil lacks commitment to the Paris Agreement. Clearly, while wildfires keep ravaging every forested region of France, French lessons in fire-fighting are just out of place!

Without exonerating Brazil’s acts of commission or omission, sources affirm that media coverage of the Amazonian fires has been misleading. It’s also difficult to believe La France. By her distinctive subtilité, she is known to skew public opinion, as she did, notoriously, in the then war against Iraq. Two centuries ago, an imperialistic France caused the Portuguese monarch to flee to Brazil. And now they’re questioning Brazil’s sovereignty over the rainforests! For sure, no country should take the high moral ground when they’re hiding charred skeletons in their cupboards.

Invaluable heritage

So, when I grieve for Brazil – the world in miniature – I also grieve for the world as a whole. I grieve for the intentional or unintentional pillage, be it cultural or environmental, of our global village. I finally remind myself that “playing with fire” is more than an idiomatic phrase; it’s indeed a sharp pointer to the invaluable, irreplaceable character of our shared, global heritage.

Pastor's Day Musings

Curiously, despite the passage of years, the idea of a Priest that first pops up in my mind is the very same one that I gathered from my father half a century ago. In those days, parents and children spent quality time together, talking earnestly about real issues, religion at the head. My father made it a point to convey his idea on how a priest should be viewed: it was obviously an upshot of his long experience with priests amidst family and friends.

Papa didn’t discuss the universal priest; he had in mind products of Rachol seminary, many of whom he knew personally. In his recent book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), published posthumously, he refers to that institution as “an excellent ornament of our archdiocese”, “an institution of such noble traditions” that produced “priests of high intellectual and spiritual merit.” He states that a large number of those cultured and virtuous priests exercised their office in Goa and in mission stations; some of them were philosophers and theologians, journalists and writers, sacred orators, canonists and moralists, teachers and public men; some others, men of edifying piety or sanctity acknowledged by the people and the Church…”

One of Papa’s favourite anecdotes was about Dom José da Costa Nunes, who held Goa in high esteem, especially for her historical and cultural past. One day, the redoubtable Patriarch of the East Indies said in a private conversation: “Goa’s clergy are cultured and pious… Here, even an obscure parish priest from the New Conquests, for example, comes forth to discuss with the Patriarch, citing, if need be, an encyclical by Pope Paul III!..”

It goes without saying that Papa was in awe of the greatest Goan exemplars of sanctity – Joseph Vaz and Agnelo de Souza – and, what is more, imagined the clergy of his day to be inching forward in the Saints’ footsteps. I guess that in the evening of his life he’d begun to sense that this was not in sight; yet, he yearned for a quick and distinct change of tide. Usually, his portrayal of a priest would close with the words: “um santo padre” (a holy priest). That was a finale we could easily anticipate.

Looking back, I would say that Papa protected his children from the knowledge of any unedifying behaviour from pastors. When confronted with information that we children had gathered, he would make little of it. And Mama would second his opinion, by saying: “Quem sabe!” – Who knows! Once it was about a Jesuit whom he held in esteem for his intellectual prowess, and presuming that his spiritual life was on par. I seized the opportunity and sought to know how Papa bore such an exalted idea of every priest. He said, quite simply: “We’ve always seen priests in a good light. By and large, our priests have been above reproach.”

Papa had a definite opinion on the apologetics and polemics of his times. His very own priest uncles, Castilho and Elínio, had been in that league. At the dinner table, he sometimes recounted stories of the journalistic antics of anti-Catholic, Portuguese republicans of the early twentieth century and how a good number of Catholic priests and laymen had combated them. However, Papa’s musings in his book end on a plaintive note: “With Vatican Council II, polemics was replaced by dialogue between religions and cultures. And with this new way of looking at things, the old type of Catholic apologist or polemist quietly faded away.”

Papa had a definite opinion on the apologetics and polemics of his times. His very own priest uncles, Castilho and Elínio, had been in that league. At the dinner table, he sometimes recounted stories of the journalistic antics of anti-Catholic, Portuguese republicans of the early twentieth century and how a good number of Catholic priests and laymen had combated them. However, Papa’s musings in his book end on a plaintive note: “With Vatican Council II, polemics was replaced by dialogue between religions and cultures. And with this new way of looking at things, the old type of Catholic apologist or polemist quietly faded away.”

And how do I end my musings on Pastor’s Day 2019? I wish our priests many fulfilling years in the Vineyard of the Lord… My children’s father may be unable to exert the same influence as did their grandfather… Let it be. Much water has flowed under the Mandovi Bridge since the days when we would sit together and ponder… After all these years all I wish, with teary saudade, is to see the vindication of the essential parts of my father’s image of the Pastor.

(Renovação, 1-15 Sept 2019, p. 14)

Dr Adélia Costa: Goa's angel of mental health

She was Goa’s best known neuropsychiatrist. The first to turn the spotlight on mental health in our land, she served the community professionally for half a century. She now lives a quiet retired life amidst close family in Miramar.

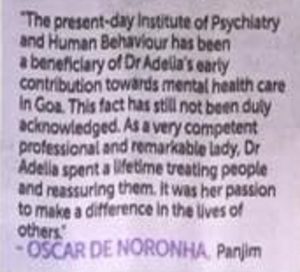

Few would know that Maria Adélia Peres e Costa, who turns 90 today, is Goa’s first neuropsychiatrist. After graduating from the Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa, she pursued specialised studies in Lisbon, becoming the first lady neurologist in Portuguese territory. On her return to Goa in 1958, she was appointed the first director of the freshly set up state-run Abade Faria hospital, now Institute of Psychiatry and Human Behaviour.

A research paper in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry states that the young director was appalled at antiquated methods of handling lunatics and bizarre practices of interning political prisoners alongside those patients! She highlighted the anomalies and suggested corrective measures, in a report that the Portuguese local government promptly accepted. At once deputed to source modern equipment and medicines from France, she returned with many goodies for the so-called “children of a lesser god”.

They eagerly waited to meet that doctor who spoke little but did a lot, that healer whose initial reserve quickly gave way to a smile and some curative banter.

Brand-new infrastructure alone can do no wonders, much less do away with stigma attached to a mental hospital. So it was the range of humane practices inspired by Dr Adélia that finally led to an attitudinal change in the staff and the public. Patients were brought out from custody to an open and friendly environment. The hospital staff became skilled at grooming the inmates and administering standard medications. Relatives and friends, too, eventually began to minister to their kin with tender love and care. A gentle revolution in healthcare got started.

By March 1962, however, Dr Adélia had sensed that the gentle revolution would not be sustainable. The resolute lady was on her final round of the hospital wards while, thousands of miles away, Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest exposing Nurse Ratched’s antics in an Oregon psychiatric hospital, was making waves for all the right reasons.

Meanwhile, Dr Adélia flew out to Portugal, this time to study psychiatry, and on her return set up private practice in Panjim. Before long, Dr Adélia became a household name, a name synonymous with mental health. Her residence and clinic was always teeming with patients, many of them from beyond the borders of Goa. They eagerly waited to meet that doctor who spoke little but did a lot, that healer whose initial reserve quickly gave way to a smile and some curative banter. Never mind the labels “nervanchi dotor” and “pixianchi dotor” contrived by the man in the street, medical cases were sure to find ethical solutions at the hands of this angel of mental health.

Dr Adélia had the makings of a model physician. Not only was she on top of the latest news and trends in medicine, she worked tirelessly, disregarding her personal ups and downs. That she could recall case histories with ease spoke volumes about her commitment. A cool head, a good listener, she was empathetic to the mental and material needs of the patients, and they never felt rushed. Even as it was striking that she always put on the white coat, it was even more so that she meticulously filed her patient treatment cards to the very end. She exuded self-confidence, yet humility was her abiding trait. And all of this came from her passion to make a difference in the lives of others.

There was an obvious connection between Dr Adélia’s faith and her life as a medico. She has been a contemplative in action

In addition to being a remarkable professional, Dr Adélia is a remarkable senhora. While fully dedicated to her clinical responsibilities, she also saw to her other obligations. After a hard week’s toil she would drive down to Loutulim in her Fiat and, later, a first-generation Maruti-Suzuki (both in classy shades of green) to spend weekends with her mother. And amidst all the chores, she still found the time to read and have a chat. And yes, she stopped to pray. She was more than just a Sunday Catholic. Her participation in the early morning Way of the Cross at the city church on Good Friday is one picture that has stayed with me since I first saw it.

There was an obvious connection between Dr Adélia’s faith and her life as a medico. She has been a contemplative in action, living out beautifully what the twentieth-century savant Alexis Carrel called “a journey of the soul towards the realm of grace.” May that marvellous cycle live on. A role model for many, Dr Adélia has spent an entire lifetime alleviating human suffering, by treating and reassuring others. She can feel blessed with the assurance that she lives in their grateful hearts and minds.

(An abridged version of this article was published in The Goan, Panjim, 27 August 2018)

http://epaper.thegoan.net/1792134/The-Goan-Everyday/The-Goan-Everyday#page/4/1

Breadcrumbs and Raindrops

Frustrating shortages of fuel, electric power, food items and even water – you and I have seen them all, but none as acute and protracted as the present one. It’s been a rough time, without water and home-cooked food... No water, despite the copious rain; no food, despite loads of raw materials at home.

If I remember right, the water scarcity scenario in Goa goes back to the 1980s. My father was indignant. No doubt Goan households had always depended on private or public wells; and Panjim, on two excellent springs (Boca da Vaca and Fénix) and retail sales of water from house to house. But, right from the 1950s, thanks to the commissioning of Opa, the capital enjoyed potable piped water round the clock. In the 1970s, however, water rationing began – the same way as commodities at ‘fair price shops’. And by the 80s, the situation was almost back to square one. Ironically, the capital city was the first to experience parched throats.

On such occasions my father’s pointed comment used to be: ‘We have joined the national mainstream!’

Much as water rationing enervated him, poor Papa would be ready with his kit – pipes, barrels, et al. – and rise to the occasion every single morning. Overhead tanks didn’t exist in the old Indo-Portuguese houses then. On days when there was no supply at all, it felt odd to hire men to fetch water from a well in the Garcia de Orta municipal garden nearby. When not even men were available, we boys did it ourselves: we carried buckets and cans across the street, much like those rural Indian women you see on TV today, trudging distances for the same purpose. On such occasions my father’s pointed comment used to be: ‘We have joined the national mainstream!’

Dear Mama would panic about having to feed seven mouths and more. No water, no cooking! And those were the days when relatives from far-flung villages, on expectant visits to charming Panjim, would sometimes drop by without notice – it was the done thing, you know! At seeing us waterless, their faces would go pale. Generally, minutes after waxing eloquent on the joys of village life, they would get down to brass tacks, thinking of ways to sort out the problem. Quite often, on subsequent visits to the city, they would bring us a few cans of water, all the way from their homes in Curtorim and Loutulim...

Down the years, through a reckless movement from a rural to a semi-urban/urban status across the length and breadth of our idyllic territory, some capital errors (pun intended) spread like an inflammation to the countryside. Who would think that in the cities, private and public wells would be filled up to make for a bonus patch of land? And who would imagine that villages would no longer hold their ancestral wells dear to their hearts? Panjim was once a hub of malaria: it hardly had potable water for its residents but enough freshwater for mosquitoes to breed in! Today, malaria and several other diseases are widespread. Clearly, ‘The Wise Fools of Moira’ (cf. Lucio Rodrigues, in Soil and Soul) and their counterparts from other villages – once upon a time, inheritors of a traditional wisdom – had sadly given in to the disastrous model of ‘development’ espoused by our ‘smart’ city kids.

It’s pertinent to note whether we are becoming smarter or dumber by the day. Or are we just getting “smart” and acting dumb? Looks like there’s a method to the madness! Consider how the ‘Traffic Safety Week’ is religiously observed every year, its main outcome being the sale of helmets and other accessories. Likewise, a water crisis born of laxity and poor accountability generates a super sale of well water and packaged water! As a corollary, eateries make a fast buck – while households remain paralysed, not for any lack of kitchen raw materials but simply for lack of water. Don’t these business feats speak volumes?

There’s no scorching summer or any disturbing drought, yet a water crisis of sorts.

Goa is fast turning into a land of shocking contrasts – ‘joining the national mainstream’, as my father would quip. The country is rich, yet the people continue to die in poverty. There’s no scorching summer or any disturbing drought, yet a water crisis of sorts. Citizens are fighting an artificial drought, yet those more equal than others have more than enough liquid to swim in. I picked up 70 litres of packaged drinking water from Mapusa and filled up our tanks with 3500 litres of well water transported by tankers, yet on my mad rounds to track down the ‘ubiquitous’ tanker, I saw restaurants and hotels functioning normally. Shocking contrasts indeed!

To be reduced to breadcrumbs and raindrops is worse than a dog’s life. But, unlike Hansel and Gretel, this trail of breadcrumbs won’t be washed away by the raindrops!

Ontem estive na Madragoa…

From now on this line is gonna be on the lips of music aficionados: ‘I was at Madragoa yesterday…’

Madragoa is a popular ward of Lisbon, close to the mouth of the Tagus. They say it's named after the Madres of Goa (the Monica Sisters of the old city of Goa) who'd invested in real estate there. Except that the ‘Madragoa’ here is not the well-heeled quarter of lovely Lisboa but a music set-up at the Centre for Indo-Portuguese Arts (CIPA) in pretty Panjim! And at Goa’s Madragoa there’s fado and mandó!

The fado and the mandó are two delightful musical genres. Interestingly, both were born in the nineteenth century, one in the dockyards of Lisbon, and the other in the salons of Salcete. Did the twain ever meet? Yes, they did – here in Goa. It is not so well known that the venerable Tipografia Rangel has to its credit the publication of one of the earliest pages of the fado in Goa… But let’s leave that for another day.

Yesterday was the premiere of the world’s first fado and mandó house. Madragoa – Casa do Fado e Mandó (House of Fado and Mando) opened not to a trumpet blast but to the exquisite strumming of two guitars and the thump of the ghumot, the Goan percussion instrument par excellence. The instrumentalists were none other than Orlando de Noronha (Portuguese guitar) and Carlos Meneses (fado guitar), accompanists to one of India’s most gorgeous vocalists: Sonia Shirsat, who – surprise of surprises – doubled as a ghumot player.

It is not so well known that the venerable Tipografia Rangel has to its credit the publication of one of the earliest pages of the fado in Goa… But let’s leave that for another day.

The show began, very appropriately, with an instrumental fado titled ‘Madragoa’, composed by Orlando de Noronha, who conceived the idea of the house. It was followed up with a charming repertoire of fado and mandó: ‘Rua do Capelão’, ‘Não rias’, ‘Sogllem mhojem vidu’ and ‘Lisboa, não sejas francesa’ in the first half. The second half featured ‘Lágrima’, ‘Fala da mulher sozinha’, and two inevitable numbers, ‘Casa Portuguesa’ and ‘Adeus korcho vellu pavlo’. Earlier, they played Portuguese guitarist José Nunes’ ‘Rapsódia’, once upon a time the signature tune of Renascença (All India Radio, Panjim’s weekly programme in Portuguese), bringing back memories of the seventies, eighties and nineties.

Pleasant memories were what the spectators were found exchanging during the brief intermission, while they relished Indo-Portuguese delicacies served with love: pãezinhos com chouriço do Reino, rissóis de camarão, fofos de bacalhau, croquetes, torradinhas com patê and pastéis de nata. And they got to leisurely sip a glass of sangria as well.

The perceptive audience carried home aural images of the fado and the mandó. Then, on social media and elsewhere, they shared the joys of Indo-Portuguese culture with friends and family, saying, ‘Ontem estive na Madragoa!’

But men and women do not live by bread alone. What they equally lapped up at Madragoa was the ambience. The backdrop to the fado and mandó room is a large mural depicting a mix of Panjim, Lisbon and Coimbra cityscapes. A narrow street called Rua da Saudade; row houses painted in blue, white, yellow and red; a chapel at the end of the street; and a clock tower overseeing the goings-on in the lyrical neighbourhood.

The perceptive audience carried home aural images of the fado and the mandó. Then, on social media and elsewhere, they shared the joys of Indo-Portuguese culture with friends and family, saying, ‘Ontem estive na Madragoa!’

Blessed by the Star

It is common for Catholics in India to assume that Independence Day was timed to coincide with the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven. This is simply not true. Whereas the state of India was released from British rule on 15 August 1947, the ancient Marian belief was dogmatically defined three years later, on 1 November 1950. Read more

Celebrating Braz and Jazz

"Raga Rock" was a much-deserved tribute to Goa-born Braz Gonsalves. Read more

Three Founders in a Row

It struck me that we have three Saint founders of religious congregations whose feasts we celebrate on three consecutive days. And all of them have a presence in Goa: