Lent: how and why

Why is the 40-day period leading to the commemoration of Jesus’s Passion, Death and Resurrection called ‘Lent’? ‘Lent’ was originally a secular word (from lencten, the Old English word for ‘lengthen’) referring to the lengthening of days in the season of spring. Over the centuries ‘Lent’ became synonymous with the liturgical period as this always fell during the springtime in Europe. Besides, it was an easier word than the official Latin Quadragesima, literally, 40th day before Easter.

That today the period from Ash Wednesday to Holy Thursday (afternoon) actually comprises 44 days is another thing. This mismatch is a result of the post-Vatican II reorganization of the liturgical year and calendar: considering that the rite of ashes had become very popular, even more than many other days of greater solemnity, it was decided to have Lent prefixed by the days from Ash Wednesday to Saturday. Minus those days, the number is 40.

Historically, Quadragesima is the bare minimum period of Lent. In earlier times there was a remote preparation comprising three weeks: the Septuagesima, the Sexagesima, and the Quinquagesima that acted as a bridge between joyful Christmas and sobering Lent. The ashes have now become a reminder that the first Sunday of Lent – the Quadragesima – is round the corner, to begin the commemoration of the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the wilderness.

That is how fasting has become inseparable from the penitential period. Earlier, fasting was throughout Lent except Sundays, in keeping with the primacy of this day as a joyful feast honouring the Resurrection of Christ. With the reorganization of Lent in 1969 it ceased to be a season of fasting. Presently, only two days – Ash Wednesday and Good Friday – are prescribed as days of fasting. For their part, Lenten Sundays play the role of shaping the week’s liturgical focus and provide the base of all the liturgy building up to Holy Week.

How long or short a period of Lent we have is finally a matter of individual choice; we know best why we abstain or refrain from certain foods; and how beneficial the season is going to be is finally left to me and my God to work out. However, if we are attuned to the liturgical seasons, we will already feel a pull towards Lent much before it actually begins; if fasting is not a matter of mere protocol we will happily go the extra mile. With the freedom we have received, we are, so to say, masters of our destiny.

Knowing the meaning and necessity of the Lenten season can help us guide our own destiny. St John Paul II summarized it well when he said: “Here then is revealed which, by its call to conversion, leads us through prayer, penance and acts of fraternal solidarity to renew or reinvigorate our friendship with Jesus in faith, to free ourselves from the deceptive promises of earthly happiness and once again to savour the harmony of the interior life in authentic love for Christ.”

That’s how and why Lent is considered a spiritual spring: we are renewed in fervour and become a vessel unto honour.

Love Him with all your heart

Lent 2020 - Day 4

“God will love you, of course, even though you do not love him, but remember if you give him only half your heart, he can make you only fifty percent happy.” - Fulton Sheen (1895-1979)

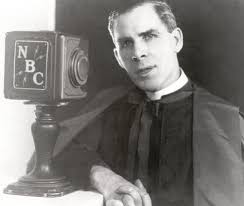

Here's yet another author that can keep us company through Lent. Celebrated Archbishop and highly acclaimed radio and TV star, Fulton Sheen's writings and recordings never fail to strike a chord.

While still a parish priest, Sheen taught theology and philosophy at the Catholic University of America. Starting from 1925, he wrote seventy-three books. In 1930 he began a weekly NBC Sunday night radio broadcast, The Catholic Hour, on which he once referred to Hitler as an “anti-Christ”. In 1946, Time magazine featured him on the cover and referred to “the golden-voiced Msgr. Fulton J. Sheen, U.S. Catholicism's famed proselytizer”, whose radio broadcast received 3,000–6,000 letters weekly from listeners.

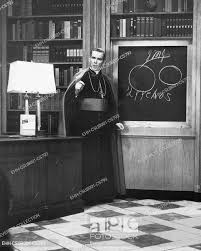

In 1940, Sheen celebrated an Easter Sunday Mass in 1940 in one of the first televised religious services. This put in motion a new avenue for his religious pursuits. In 1952, he moved to TV, presenting Life is Worth Living. It comprised unpaid Sheen simply speaking in front of a live audience without a script or cue cards, occasionally using a chalk board. Here he denounced the Soviet regime, saying, "Stalin must one day meet his judgment." The dictator died within a week.

Did Cardinal Spellman drive Sheen off the air when Life is Worth Living was at the height of its popularity? Sheen never talked about the situation; he even praised Spellman in his autobiography titled Treasure in Clay: The Autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen (1980) and made only vague references to his “trials both inside and outside the Church.”

In 1958, Sheen became national director of the Society of the Propagation of the Faith and, eight years later, Bishop of the Diocese of Rochester, New York. From 1961-68, Sheen’s final presenting role was on the syndicated The Fulton Sheen Program. Through his career, Sheen helped convert a number of notable figures to the Catholic faith. Each conversion process took an average of 25 hours of lessons, and reportedly more than 95% of his students in private instruction were baptized.

Just before his retirement, Sheen was appointed archbishop of the titular See of Newport, Wales. Two months before he died, when Pope John Paul II visited St Patrick's Cathedral in New York, he embraced Sheen, saying, "You have written and spoken well of the Lord Jesus Christ. You are a loyal son of the Church.”

Today, the Fulton J. Sheen Museum in Illinois houses the largest collection of Sheen's personal items and the Sheen Center for Thought & Culture, Manhattan takes his name. In 2009, his shows began rebroadcasts on the EWTN and the Trinity Broadcasting Network’s Church Channel cable networks. Sheen's contribution to televised preaching makes him one of the first televangelists.

Today, the Fulton J. Sheen Museum in Illinois houses the largest collection of Sheen's personal items and the Sheen Center for Thought & Culture, Manhattan takes his name. In 2009, his shows began rebroadcasts on the EWTN and the Trinity Broadcasting Network’s Church Channel cable networks. Sheen's contribution to televised preaching makes him one of the first televangelists.

The cause for Fulton J. Sheen's canonization was officially opened in 2002. He is now Venerable. And venerable is also his large body of writings and talks.

Accepting the Cross

"Each one of us has a cross to carry. Each one of us would like to be something he is not, to have something he has not, to be able to accomplish something he cannot. We need to let go of being what we are not, having what we have not, and accomplishing what we cannot; this is the way for all of us." - Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira (1908-1995), in 'Reflections on the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ' (https://www.tfp.org/lenten-reflections/)

In touch with the Society for the Defence of Tradition, Family and Property (TFP) for a decade (1989-1999), its Founder's spirituality came easily to mind in my quest for Lenten reading. Here are a few notes on the man whose life can't fail to touch a committed Christian:

Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira was a Brazilian intellectual and Catholic activist. At 24 he became the youngest congressman in Brazil's history and a leader of the Catholic bloc. Valuing his Catholic faith above all else, he turned his back on a political career and served the Church. He taught Modern and Contemporary History at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and was editor of the Catholic weekly Legionário. In 1951, he founded the magazine O Catolicismo and later was a columnist for Folha de S. Paulo, the city’s largest daily.

Dr Plínio (as he was fondly known) was an avowed Thomist, his political ideology anti-Communist. To counter the school of liberation theology and the Cuban revolution, he founded the TFP in 1960. He decried the reforms of the Second Vatican Council but remained devoted to the Chair of St Peter.

Dr Plínio is the celebrated author of fifteen books and over 2,500 essays and articles. Some of his works are: In Defence of Catholic Action (1943); Revolution and Counter-Revolution (1959), a seminal treatise that inspired the founding of autonomous TFP groups in several countries worldwide; The Church and the Communist State: The Impossible Coexistence; and Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites in the Allocutions of Pius XII, his swan-song.

Dr Plínio's writings have the mark of an intense interior life. He had deep confidence in the Blessed Virgin Mary. An unparalleled twentieth-century crusader for a Christian Civilization, and the final victory of good over evil, he believed in the words of Our Lady at Fatima: “Finally my Immaculate Heart will triumph!”

After Dr Plínio's death, there was a split in the TFP. Eight co-founders took charge of the organization while a large chunk led by Mgr. João Clá Scognamiglio Dias left to set up Heralds of the Gospel. The new group, open to the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, was recognized as an International Association of Pontifical Right, the first one established by the Holy See in the third millennium. They are now present in 78 countries.

Mgr. Dias eventually got back control of the TPF, now devoid of its former glory. Meanwhile, the original co-founders of the TFP set up Instituto Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira (IPCO) to carry on the Founder’s ideology and activity. IPCO is associated with the TFPs and similar organizations worldwide, like the TFP was before their division.

In 1989, the TFP paid tribute to their Founder in a book titled O Homem, Uma Obra, Uma Gesta. Dr Plínio has many other biographies, two main ones being The Crusader of the Twentieth Century, by Roberto de Mattei (1998) and Rencontre avec Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira - Défenseur de la Chrétienté, by Mathias Von Gersdorff (2019). Earlier, regretting the absence of an autobiography, IPCO published Minha Vida Pública (2015), an anthology of writings that throw light on the life and mission of the man.

Knowing Dr Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira’s ideals fills a Christian with hope. His profound analysis of history and world events and his supernatural approach to life - a loving acceptance of the Cross - can uplift the most disheartened soul. To me, a decade with Dr Plínio was worth a lifetime.

Heralds of the Gospel, https://www.arautos.org/

IPCO, https://www.pliniocorreadeoliveira.info/biografia.asp)

The Springtime of Lent

On the look-out for inspirational authors to read this Lent, I first thought of the old classics. But then I chanced upon a twentieth-century author: Therese Mueller, born in Germany, in 1905. An academic (economics and sociology) married to sociologist Franz Mueller, they were liturgical pioneers and involved in the Catholic youth movements in their country.

In 1940, the arrival of the Nazi regime interrupted their lives. The Mueller family migrated to the United States where people got interested in their faith experiences in Europe. Therese, with her sociological background, got vocal on how the liturgy could be taught and shared amidst a family. Her articles were compiled into a pamphlet titled Family Life in Christ (1941). Later she wrote Our Children’s Year of Grace (1943) and The Christian Home and Art (1950). These publications are an expression of her experiences as a wife and mother.

The Muellers eventually settled in St. Paul, Minnesota. Franz lectured at St Thomas University, while Therese taught part-time at St Thomas and at the College of St Catherine. The couple wrote and spoke about the Christian home as a crucial dimension for the liturgical life. Franz died in 1994 and Therese in 2002, leaving behind an eloquent life example of lay priesthood.

Here's an excerpt from Therese Mueller's Our Children’s Year of Grace (recently reprinted by Martino Fine Books, ISBN-13: 9781684222445), aptly describing the fruits of the springtime of Lent:

"We prepare for the renewal of our baptism, we suffer with Christ for our sins, we are buried with Him so that we may also arise with Him to a new life of grace and glory."

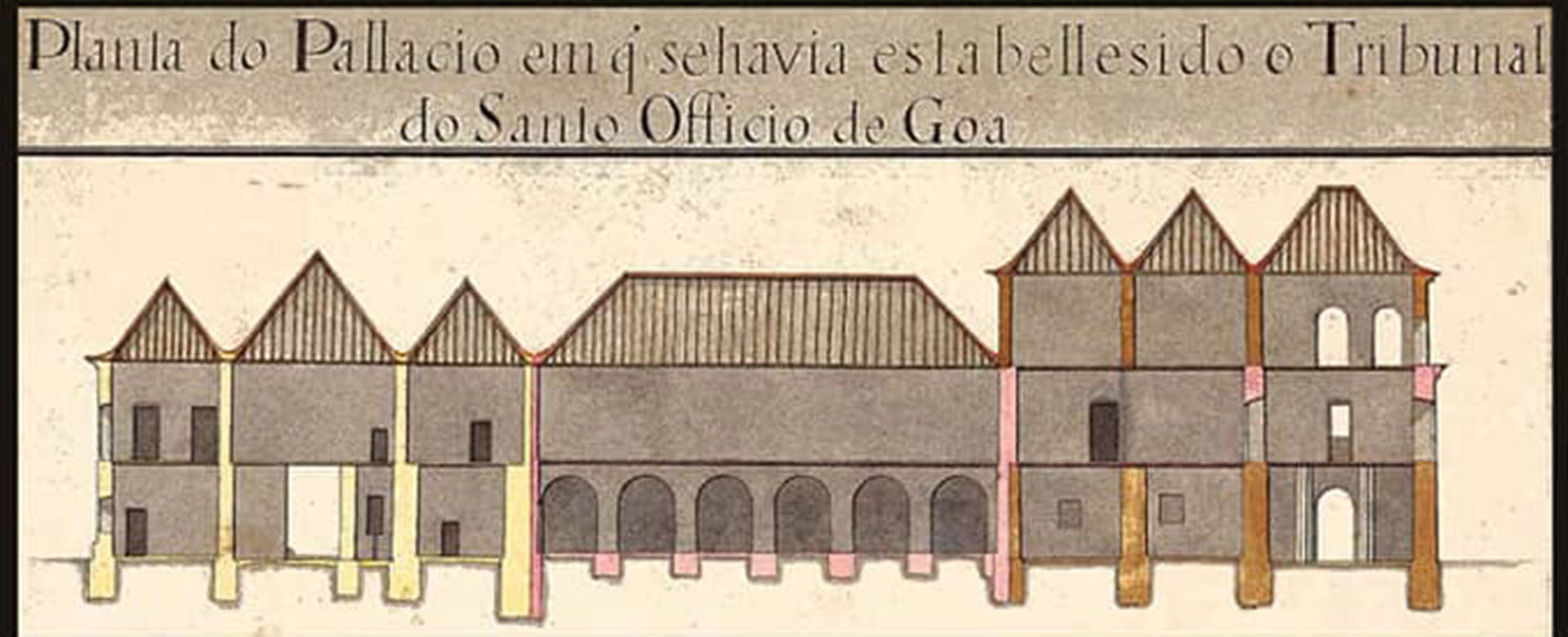

Why the Inquisition in Goa

At Instituto Camões, Panjim, Professor José Pedro Paiva of the University of Coimbra provided a lucid rationale for the establishment of the Tribunal of the Inquisition in Goa (1560-1812). His talk was titled "Reasons for the Founding of the Goa Inquisition in 1560". He stated, among other things, that even prior to the arrival of St Francis Xavier the Religious had endeavoured to establish the Tribunal in Goa.

For my part, convinced that no serious student of history should depend exclusively on Charles Gabriel Dellon's much-quoted account titled Relation de l'Inquisition de Goa (1687) and Bombay-based A. K. Priolkar's expedient interpretations of the Frenchman's allegations, I asked the erudite Professor where one would find fresh archival sources to counter their claims. He pointed to the Portuguese and Brazilian archives.

Without a doubt, the Tribunal, like every human enterprise, had its shortcomings; but having said that, by no means do Dellon and Priolkar deserve a clean chit. While the testimony of the former, who was tried and incarcerated by the Tribunal, is largely suspect, the latter's narrative fails to contextualize the institution, and his vitriolic language hardly behoves a researcher. It is curious to note that his work appeared in the year 1961, a watershed in the history of Goa and Portugal.

It is a pity that there has hardly been any comprehensive study of the Goa Inquisition, particularly in the English language. And alas, just as a big lie told frequently enough is finally believed, unsuspecting readers have found themselves trapped in a web of lies regarding the nature and purpose of the Inquisition. It is heartening that a younger crop of researchers has been shedding fresh light on the subject and overturning previous findings or misplaced conclusions.

Meanwhile, as the matter in question often boils down to the number of deaths at the stake, I was keen to know details of the same. The exact figure will never be known, since the relevant papers are unavailable, for reasons too complex to mention here. However, Professor Paiva authoritatively stated that, based on the lists of names available in Lisbon, the number of trials held in Goa, over a period of 250 years (1560-1812), are reckoned at 14,000 and the convictions at 800, the average thus being 3.2 deaths per annum.

Comparisons may be odious, but can we overlook the odious crime of human sacrifice perpetrated in Indian society outside the borders of Goa during that same historical period? Some of them had religious sanction, others were committed arbitrarily, but none gave any scope for self-defence or mercy. Similarly, who can deny that the number of convictions by criminal courts far exceeded the inquisition tribunal's annual average of convictions?

Finally, those numbers pale by comparison to the political and other inquisitions at work in the twenty-first century, many of which - please note - do not have even the semblance of a tribunal or a fair trial. Hence, a sense of history and fair play are a must to understand the rationale behind the Inquisition tribunal set up in Goa way back in the sixteenth century.

Herald at 120!

I'm a fourth-generation reader of Goa's first daily. As much as I grieved the loss of the Portuguese edition in 1983, I looked forward with great anticipation to Herald as we know it today. Its arrival was timed to more or less coincide with the Commonwealth Heads of Government Retreat in Goa, which the paper then covered most delightfully. Eventually, Herald acquired a great reputation, thanks to its sustained campaign for recognition of Konkani as official language and Statehood for Goa. The paper has since been firmly ensconced in the heart of every Goan. I sincerely hope that Herald will continue to earn the trust and confidence of its readers and writers and forever be a people's paper par excellence.

(Herald, 26 January 2020, p. 22)

Tribute to my Father

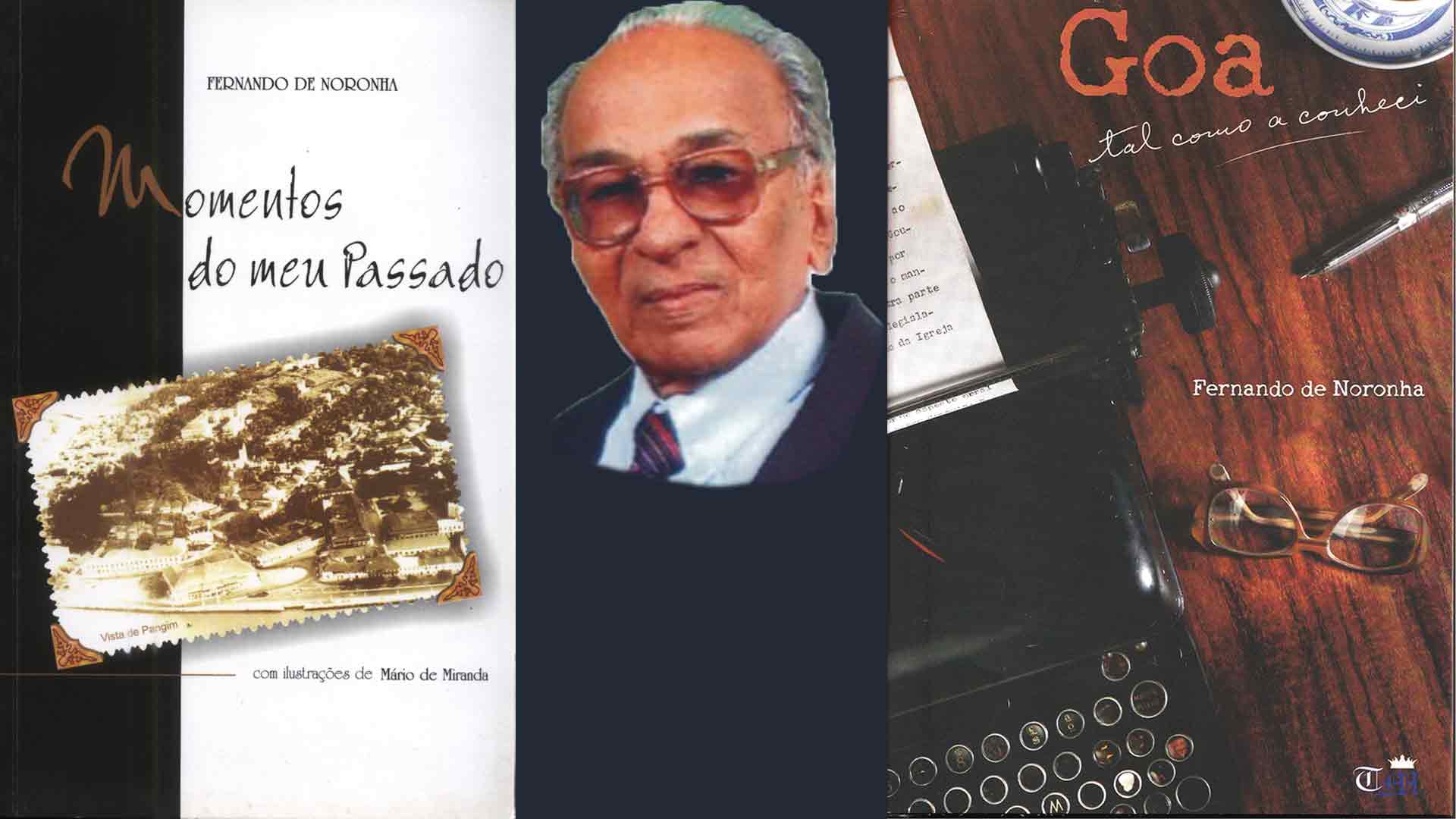

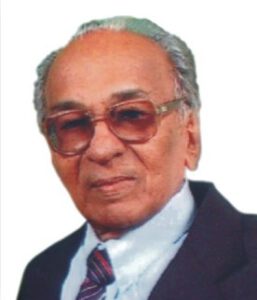

Early this month the social media was abuzz, in anticipation of the twenty-twenties; as for me, I was on a solo trip back to nineteen-twenty. As a child, this year had the earmarks of a happy milestone for me, yet it triggered anxiety for the future. My childhood was a shrine of happy pictures, yet the thought of that golden marker fading into the horizon would fill me with sadness. Why? Because while a young me was looking ahead to what would be, my father Fernando was already looking back upon what had been….

My lone source of anxiety for the future was that I was the eldest child, born in Papa’s forty-fourth year. I knew not how long I would have him: it was a worry I kept to myself so as not to dishearten him. But then, hardly anything disheartened him; he kept pace with his children and even his grandchildren’s progress, and enjoyed the sleep of the just. When he passed on, at 91, he was a grandfather to fifteen. His abiding trust in God was the secret of his longevity – as well as a salutary lesson on the futility of anxiety.

In my naiveté, 1920 still felt charming; as I grew older, I found Papa’s idealism, independence and integrity appealing. I looked up to him, especially because his life hadn’t been easy: the ‘roaring twenties’ of the West had played out quite differently in Portugal and Goa. Following a decade of political turbulence and galloping inflation, the country stabilised and the escudo roared upon the rise of Salazar the economist. Convinced that he was a man with ‘the right intention’, my father held him in esteem for his intellect and honesty – the antithesis of leaders in sham democracies.

After God, it was Goa uppermost in Papa’s mind. The Mass and the Bible alongside spiritual classics were his daily fare. To compensate for arid bureaucratic matters, he put his faith in reading, writing, teaching and music. Even while he took delight in the Romantics Eça, Camilo and Ramalho, he recommended some excellent Goan writers. Until his last breath he lapped up the masters of the Portuguese language, not forgetting two of our very own Goan purists, Costa Álvares and Filinto C. Dias.

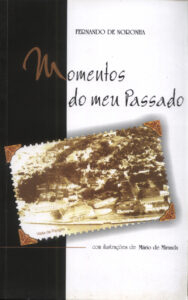

One gets a bird’s eye view of Papa’s outlook from his first book, Momentos do meu Passado (Moments from my Past). Much of it is what he used to recount animatedly at the dinner table or talk over with relatives and friends. He obliged us by writing this slim volume comprising ‘figures, facts and facetiae’: pen sketches of over thirty personalities from the Goan social and political milieu; some little-known facts of contemporary history; and a host of anecdotes dating back to his Lyceum days. In his words, he wished ‘to quench saudades of a not so distant past, when one lived in a happy and carefree manner unique to Goa.’

It took me some time to appreciate Papa’s simple and straightforward nature. And noticing how people would often agree but also end up severing ties with him, I learnt that truth can indeed puzzle, confound, hurt… Papa’s intermittent observations on public affairs are lost in the thicket of Heraldo and A Vida for, whilst a bureaucrat in two key departments during the Portuguese regime, he used pen names of which he kept no record. In 1967, his commitment to ferry people to the booths on the occasion of the Opinion Poll (16 January, his birthday and feast of St Joseph Vaz) fetched him a resounding office memo.

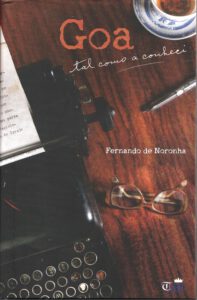

It warms the cockles of our hearts to see that Papa’s second book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), contains the essence of his views on people, events and ideas. Covering as he did twentieth-century Goa’s political and administrative affairs, society, culture, and religion, in a total of eighteen chapters, this offering is a testimony of love for the land and the people. It is also a tribute to the Portuguese language that was so dear to him. After opting to retire from public service, he taught that idiom at a city college and co-founded a weekly, A Voz de Goa. At Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church he prayed in that ‘language of the angels’ and put together a choir at Sunday mass.

Music was high up on his agenda ever since his father purchased a gramophone and a maternal uncle and self-taught violin virtuoso played along. An attractive feature of Papa’s day was his whistling and playing of the harmonica, providing the household with a kind of crash course in classical and semi-classical music. The mandó moved him very especially (he ensured that it featured at his children’s wedding parties) and so did two popular Konkani films of his time which, he said, ‘foster Goan patriotic feelings’. The Goan reality, however, was a far cry from what he had envisioned, so I can say with Wodehouse that ‘if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.’

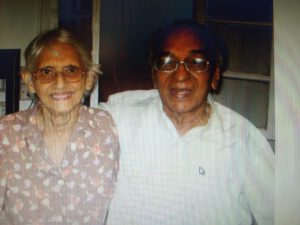

No tribute to our father would be complete without a reference to our dearest mother Judite da Veiga, who was the love of his life, the reason of his being. On his death bed I heard him thank her for half a century of togetherness. She, their five boys and families, was all that he ever wanted. We have lost him in body, not in spirit. He has become greater in death, our strength and consolation, our conviction that there can be no anxiety for the future….

Herald, 19.01.2020, published an abridged version

For this full version see Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), March-April 2020

https://issuu.com/casadegoa/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n3_-_mar-abr_2

When the soul feels its worth…

Does the run-up to Christmas sometimes feel like a wild-goose chase? When the painters don’t show up; the newest dress catalogue is a let-down; the much-awaited mechanized crib is a non-starter, and there’s no Christmas tree and star worth the name in the city shops... As if that weren’t enough, there’s no turkey in town, and we have to literally start chasing geese!

Does the run-up to Christmas sometimes feel like a wild-goose chase? When the painters don’t show up; the newest dress catalogue is a let-down; the much-awaited mechanized crib is a non-starter, and there’s no Christmas tree and star worth the name in the city shops... As if that weren’t enough, there’s no turkey in town, and we have to literally start chasing geese!

‘A poor life this if, full of care, we have no time to stand or stare,’ W. H. Davies would say. Alas, the weariness, the fever and the fret increases by leaps and bounds as we draw closer to Christmas. There’s a mad rush online, long queues at the mall, frightening street jams, hullabaloo at home. It is as though the celebration is an end in itself.

Isn’t Advent supposed to be a time of expectant waiting and preparation for the Nativity of Jesus? Flippant though it may sound, today it’s more about waiting for Flipkart orders to arrive and set the tone for the Christmas preparation. Where, then, is that time to stand and contemplate the Babe of Bethlehem?

They say the best part of the celebration lies in waiting for it; but that’s only for those who can wait! On four Sundays preceding Christmas, candles are lit, representing hope, faith, joy and peace, all part of a tradition rich in symbolism. Sadly, with a decline in our capacity for spiritual expectancy and enjoyment, we simply gloss over those milestones. We are a generation of instant, material gratification.

It would be interesting to figure out how to spend this time of the year more meaningfully. To my mind, the accent should be on being ourselves rather than doing a million things. For sure, we must have put up the crib, the tree, the decorations; we do need the bells, the light and the music; and without the gifts and the family dinner, Christmas may feel incomplete.

But then, these acts should be symbolic of our self-giving to the Child Jesus; they should not be about self-serving. Those acts should finally translate into works of love towards our fellow human beings, and not make us complacent.

Pope Francis’ recent exhortation on how to spend Christmas is reassuring: we have to incarnate Christmas. For instance, one way to personify the Christmas pine is to resist life’s vigorous winds. We will bring alive the Christmas decorations when an array of virtues adorn our life. Jingling bells must be an invitation to one and all to gather and feel as one.

There is no doubt that the angel, the star and the Magi are some of the most enduring images of the Christmas tableau. Like the angel who sang ‘Gloria in Excelsis Deo’, we have to be harbingers of peace, justice and love. We have to be a guiding star to persons seeking the true God. In all that we do, we have to do as the Wise Men did: give the best of ourselves to the Lord.

When our being is one harmonious whole, our voices will produce the joyous music of Christmas. We will become instruments of peace and harmony in society. We will be the light of Christmas, illuminating others’ path with kindness, patience, joy and generosity. Our life will be a gift to everyone in need. The season’s greeting cards will magically convey our tender love and care.

And when everything is said and done and our Christmas dinner is underway – shared with someone who has no dinner to share with us – we will experience the presence of the Divine Infant in our midst. That night will be an expectant waiting and preparation for a new dawn, a new hope, a new life... Then there’ll be no wild-goose chase; we will be at peace with ourselves, thankful to God for what we are and what He has given us. Focused on Christ, we will be the salt of the earth and the light of the world.

Eventually, thoughts of how life had been a mad, mad rush in the bleak mid-winter, that is, “till he appeared, and the soul felt its worth,” will warm the cockles of our heart. From then on, every day it will be Christmas.

(The Goan, 25.12.2019)

Simple and Sublime

The Christmas tableau is a heart-warming story in miniature. As a child I was moved particularly by those poor shepherds huddled up on the cold hills of Bethlehem; they were the only ones to hear “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” that mystical night. I was also enthralled by the Magi, whose regal aura perfectly balanced out the divine narrative. After all, Jesus not only descended from the House of David, he descended from Heaven and made his dwelling among us. Here was real majesty, with no hint of extravagance.

The Christmas tableau is a heart-warming story in miniature. As a child I was moved particularly by those poor shepherds huddled up on the cold hills of Bethlehem; they were the only ones to hear “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” that mystical night. I was also enthralled by the Magi, whose regal aura perfectly balanced out the divine narrative. After all, Jesus not only descended from the House of David, he descended from Heaven and made his dwelling among us. Here was real majesty, with no hint of extravagance.

With two thousand years of the Nativity behind us, we surely have the benefit of hindsight. The multitude then perhaps failed to appreciate the wondrous event; and the few enlightened ones were so meek and mild that the likes of Herod exploited the situation, apparently frustrating God’s plans for humankind. The king and his minions even drove Christ to his death but, thankfully, his resurrection soon became the very foundation of the Christian faith.

There was a mighty coherence to Jesus’ life story. His rise from the tomb established his reputation as a Man-God. Were it not for Easter, Christmas would have gone down in history as a non-event. In fact, the Bible does not specify Jesus’ date of birth; and in the first two centuries, none paid attention to it anyway, as birthday celebrations were considered a pagan custom. Saints and martyrs were remembered on their day of death, which marked their entry into Heaven. Hence, theologically, Easter ranks higher than Christmas.

However, considering the tender feelings that birth evokes, Christmas was poised to be a cherished day. Based on patristic sources that dated Jesus’ conception (and crucifixion) to 25 March, St Hippolytus of Rome (c. AD 204) was the first to explicitly assign Christmas to its current feast day. For their part, the Romans had long been observing 25 December as Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (‘birthday of the unconquered sun’), so when in AD 325 Constantine I, the first Roman Christian Emperor, declared Christmas a holiday, the relation between the rebirth of the sun and the birth of the Son of God became more than obvious.

Half a century later, Pope Julius I formalised the date; yet Christmas would continue to be celebrated in close association with the day of Jesus’ baptism (6 January) for a long time to come. On this day some Eastern Orthodox Christians still observe Christmas side by side with the (revelation of the Infant Jesus to the Magi), while in accordance with the Julian calendar, Greek and Russian Orthodox churches commemorate Christmas on 7 January.

Celebration of Christmas struck root in the medieval ages. It gained impetus with Charlemagne’s crowning on that day in AD 800. The century also saw the creation of a special Christmas liturgy, although not on a par with that of Good Friday and Easter. But by and by Christmas developed a unique, visible identity, not least with the pine tree planted by St Boniface, as a pointer to Heaven; the old tradition of carol singing that was lent a heavenly form by St Bernard of Clairvaux; the crib, invented by St Francis of Assisi as a means of imparting the Christmas story, and so on.

Curiously, the more Christmas gained acceptance, the more it began to vary across countries, social and political eras, and Christian denominations in the post-Renaissance period. With changing values and norms, new customs were born while some of the older ones just hung on: the eye-catching star, the bright little candles, the sweet-sounding bells, and the intimate, family dinner, to name just a few elements that over time ensured that the divine occurrence became instantly relatable across cultures.

Christ’s coming was a watershed moment in the history of the human race. But the tableau typical of post-industrial society is so highly romanticised that we miss out on the chequered history and rich symbolism of the Nativity. Millions attend Mass on the world’s most prominent holiday, only to top it up with a secular, not to say raucous, celebration. Here the divine protagonist is easily forgotten and Santa the antagonist highlighted. In short, we forget the reason for the season.

With half a century of Christmases behind me, I feel more and more concerned about our collective failure to grasp the mystery of the joyous occasion. How I yearn to approach the manger with the simple heart of the proverbial shepherd and the sublime mind of the famed Magi!

(Herald, 23.12.2019)

The Last Things – First!

“In all thy works remember thy last end, and thou shalt never sin.”

(Ecclesiasticus, 7:40)

When we lose a loved one, our hearts ache and a great unease pains our sense. Wrestle how we might, we come to accept the reality only after we have decided, like Keats in ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, that to them ‘now more than ever seem[ed] it rich to die, to cease upon the midnight with no pain’. Eventually, we gratefully recognize that history had been unfolding before our very eyes through God’s infinite wisdom, mercy and goodness. Peace descends on us and the former unease turns into a wish simply to remain spiritually united with the departed soul.

Taking in the inexorable mystery of death – and, specifically, the passing away of a near and dear one – is an important milestone in our lives. Helen Keller once said apropos the proper use of the physical senses: “Sometimes I have thought it would be an excellent rule to live each day as if we should die tomorrow. Such an attitude would emphasize sharply the values of life. We should live each day with a gentleness, a vigour, and a keenness of appreciation which are often lost when time stretches before us in the constant panorama of more days and months and years to come. There are those, of course, who would adopt the Epicurean motto of ‘Eat, drink, and be merry’, but most people would be chastened by the certainty of impending death.”

Many of us would also wish to gaze beyond our earthly life, seeking to understand what is to become of us after death. And should we wonder why we are born at all if we are to die some day, we will realize that there is more to life than just this earth. It requires only that leap of faith to see that, like matter, the soul changes its form but is never destroyed; that life returns to where it has come from: the bosom of the Lord!

Communion of Saints

Catholic doctrine has comforting answers to the eternal questions of Life and Death: it would be of immense spiritual profit if we learnt them in time, so that whether or not we gain this whole, wide world, we might be poised to earn the next!

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) teaches us that, living or dead, when in a state of grace we live in Christ as ‘saints’; that there is the church of heaven and of earth, where the saints live in communion with each other and with God, much in the manner of the Triune God!

The CCC emphatically says, “What is the Church if not the assembly of all the saints? The communion of saints is the Church,”[1] and goes on to explain that the term has two closely-linked meanings: communion in holy things and in holy persons.[2]

The communion in holy things or spiritual goods comprises (1) the faith received from the apostles and kept alive through prayer; (2) the sacraments, most importantly the Eucharist; (3) the charisms, or graces that the Holy Spirit distributes among the faithful for building up of the Church; (4) our possessions, which are, really speaking, the Lord’s goods under our stewardship; and, finally, (5) love, whereby if one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honoured, all rejoice together.

The communion in holy persons refers to the life that the saints of heaven and earth live in common. While some of Christ’s disciples are still pilgrims on earth, others have died and are being purified; yet others are already in glory, contemplating God in full light. The exchange of spiritual goods, while it helps the departed to attain the Beatific Vision, also makes their intercession for us effective. Finally, being more closely united to Christ, they fix the whole Church more firmly in holiness.

In his book True Spiritualism, Fr. C. M. de Heredia, S.J., calls the Communion of Saints “a Divine Corporation, a great communism in which all the saints in heaven and all the souls in purgatory and all the children of the Church on earth form one vast family, of which Christ is the head, and participate in all spiritual goods that are in common.” The early Christians in Jerusalem “had but one heart and soul; neither did any one of them say that, of the things which he possessed, anything was his own; but all things were common to them. [...] And those who had houses and lands sold them and laid the price at the feet of the Apostles who distributed them to every one according to their needs.” (Acts 4: 32, 34) The Communion of Saints is this same idea “raised to the heavenly sphere, embracing both planes of existence, enveloping the finite world and entering into the infinite, the idea that makes common property not so much of earthly as spiritual goods.”[3]

Vocation of the Church

The CCC says, “If we continue to love one another and to join in praising the Most Holy Trinity – all of us who are sons of God and form one family in Christ – we will be faithful to the deepest vocation of the Church.”[4]

What is the deepest vocation of the members of the Church? It is to know God, love Him and serve Him. So it behoves us to learn how to do all these things! We should (re-)arrange our worldly priorities so that God becomes the centre of our lives and is forever praised in all that we do. On balance, this is what holds out the eternal reward after our life in this valley of tears!

“It has been alleged oftentimes,” says De Heredia, “that the Church has taught that in this world there is nothing but misery, and that she is not for this life but for the next. Well do we know how erroneous that is! As the soul is greater than the body even in this life, so does it follow that the pleasures of that soul are greater than the pleasures of the body. It is the Church which teaches us how to be happiest in this life and happiest in the next. The philosophy that reduces the world’s playthings to their proper perspective and makes man at once great in the accomplishments of earth and at the same time divinely indifferent to them is hers. [….] No hedonist, no aesthete, however rapturous his pagan worship of beauty, can equal the Catholic even in pursuit of earthly happiness.

“But immeasurably beyond these sources of joy, the Catholic has his firm hope in the everlasting happiness of heaven. He has his trust in a God who loved man so much that He came to earth and died for him. The light of Paradise is in his eyes. The beauty of God illuminates his soul. The caresses of his Heavenly Father are on him. And he has his belief in the power and companionship of the Communion of Saints.”[5]

Last Things First!

The communion of saints is a marvellous reality.[6] But this can be fully appreciated only against the background of eschatology, the teaching about the ‘Four Last Things’: death, judgement, heaven and hell. These apply to the individual, while the resurrection of the bodies and the final judgement at the second coming of Christ are for the human race as a whole.

Knowledge about the ‘Last Things’ is best not left for the last moment (as St Francis of Assisi says, “We shall die sooner than we expect”). We are duty-bound to see that the ‘communion of saints’, ‘the forgiveness of sins’, ‘the resurrection of the body’, and ‘the life everlasting’ from the ‘I Believe’ are not mere words but operating realities! We must understand that the ‘hour of death’ that the ‘Hail Mary’ reminds us of is not just another moment in a distant, even undefined, future but could come sooner than later! And we who recite the ‘Our Father’ and assist at Mass would do well to learn what is meant by the ‘Kingdom’ and ‘Eternal Life’! Such fundamentals of our faith have to be transferred from the tomes of theology to the homes of everybody – meditated upon, discussed, internalized, and acknowledged in our daily life. Or even a prayer, like the following one to St Joseph, composed by none other than Pope Pius X, points to the true worth of those concepts.

O Glorious St. Joseph, a model for all who are devoted to labour, obtain for me the grace to work in a spirit of penance, for expiation of my ma ny sins; to work conscientiously, putting the call of duty above my inclinations; to work in recollection and joy, deeming it an honour to employ and develop through labour the gifts received from God; to work with order, peace, moderation, and patience, never shrinking out of weariness and trials; to work, above all, with purity of intention and with self-detachment, having ever before my eyes death and the account that I will have to render of time lost, talents wasted, good omitted, and vain complacency in success, so baneful to God’s work.

ny sins; to work conscientiously, putting the call of duty above my inclinations; to work in recollection and joy, deeming it an honour to employ and develop through labour the gifts received from God; to work with order, peace, moderation, and patience, never shrinking out of weariness and trials; to work, above all, with purity of intention and with self-detachment, having ever before my eyes death and the account that I will have to render of time lost, talents wasted, good omitted, and vain complacency in success, so baneful to God’s work.

All for Jesus, all through Mary; all after thy example, O Patriarch St Joseph! This will be my watchword in life and in death. Amen.

This is eschatology made simple... eschatology in action! We are gently reminded that this world and the next are seamlessly woven into one whole; that what we do now – and how we live and work – determines our later fate.

It is easy to see that the Last Things are relevant not only to the afterlife but also immensely so to our present life. By letting us realize our final end, they bring about the required change in our worldview. They determine our dreams and aspirations as well as our response to earthly trials and temptations; they shape the nature of our hope and our way of life. They teach us why it is natural to seek first the kingdom of God and its justice; and how to be in the world and not of it.

It is surprising that we Catholics seldom talk actively about the Last Things. It is as though a conspiracy of silence is militating against our understanding them fully, thus even giving Eternal Life a semblance of fiction. Alas, we fail to realize that, by ignoring this real important aspect of our Christian existence, we let pessimism and despair cloud our consciousness. This is truly asphyxiating for the Catholic soul.

On the other hand, the greater our engagement with the Last Things the better it is for God’s people. A culture of hope and consolation is fostered, lending that much-needed supernatural quality to our being. We begin to live an integrated Catholic life. The communion of saints in heaven and earth is made active, and the Kingdom comes.... All good enough reasons to put the Last Things first!

(Renovação/Renewal, Goa, 16-31 August 2011)

[1] CCC 946

[2] The communion of saints is not linked to ‘spiritism’ (contact with the dead), which is disallowed by the Church.

[3] C. M. de Heredia, True Spiritualism, P. J. Kenedy & Sons, New York, 1924, p. 9-10

[4] CCC 959

[5] Op. cit., p. 28-29

[6] Whoever doubts this may refer to a simple little book, Read me or Rue it, by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P., TAN Books, 1992 (First published in 1936, with approval from His Eminence the Cardinal Patriarch of Lisbon): It carries captivating true stories about the Poor Souls in Purgatory.