St Joseph Vaz's Letter of Bondage

Remembering Prima Maria

November 1987. I was all of twenty-two years old and had landed in Lisbon. Shortly after this I phoned a relative for whom I’d carried a little parcel from her sister Genoveva (to whom I became a sobrinho by marriage but remained first a primo, via Curtorim). Her name was Rita Maria Gomes. I’d never met her before; yet she sounded so warm that I promptly accepted her lunch invitation. Her brother Nicolau stopped over to collect the item, early the next morning, shaking me out of my jet lag: he was my only visitor at Hotel Berna, Campo Pequeno, where I’d put up in the first three days of my year-long stay in Portugal.

After my maiden Sunday Mass na terra de Camões, I headed for Carcavelos, half an hour’s journey by train from Cais do Sodré. Usually shy at a first meeting, I was nonetheless eager to see my mother Judite’s “Guirdolim cousins”.

At Oeiras, on a near-empty platform, Primo Amâncio Frias Pinto and I easily spotted each other. As he comfortably drove me home in his white Renault 10, his down-to-earth style put me at ease. And then, when Prima Maria and the family welcomed me, I noticed the glow on her face: she had taken a shine to Judite’s son. My gracious hostess had very thoughtfully invited three primos still new to me: Noémia and her children Lena and Stuart. I instantly identified the senior one (now a much-loved Tia) as daughter of Primo ‘Picu’ Stuart, who I’d been very fond of as a child… Now here was a heady mix of Neurá and Curtorim/Guirdolim, and it made my day!

I have no photographs of that memorable coming together. That was altogether another age, the pre-digital age! I vividly remember, however, that the apartment was bathed in sunlight. Prima Maria had the table laid de rigueur and served a full course meal. It wasn’t easy, but she did it! And, yes, she kept up an animated conversation, centred on Goa, our relatives and friends.

It was still a bright and pleasant afternoon when Prima Maria suggested we take a stroll in the colourful feira nearby. And soon it began to feel like home. When evening came and Primo Amâncio (who’d been my father Fernando’s contemporary at Casa de Estudantes) dropped me off to the station, I felt a sudden pang of saudade…

..........................................................................

August 2018. Years after my unforgettable passage to Portugal, I met the simpático casal at their ancestral house at Ararim, Socorro – which, meanwhile, I’d become familiar with as the home of my wife Isabel’s maternal aunt Bernadete married to Terêncio Frias Pinto. Prima Maria made a few more trips to Goa, travelling solo after her husband’s demise. Last year, we crossed paths at Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church. That’s when I quickly fixed up a lunch appointment; and unable to meet up at home, we decided on a thali at the Fidalgo.

How can we forget the people who’ve made us happy at some time or other in our lives? I’m glad I started off by recalling the lovely moments spent with her family – oh my God! – three decades ago...

As for her, she was soaked in memories. She smiled wistfully, reminiscing about her spinster days in Goa and as a young wife in Mozambique, and gave me the lowdown on her life as a widow.

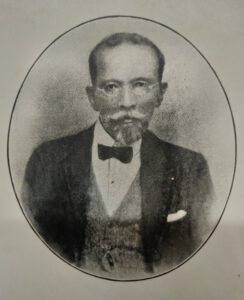

A grandmother of two, pretty even at eighty, Prima Maria was proud of her Gomes ancestors who made it big in Portugal. She spoke ardently about the Veiga-Gomes kinship, and – surprise of surprises – she pulled a neat set of notes and sepia out from her handbag to confirm that the doctor-politician Pestaninho da Veiga (1849-1901), the physician-writer A. X. Heráclito Gomes (1864-1934), and the poet Mariano Gracias (1871-1931), who died in Lisbon, were indeed first cousins! Prima Maria was thus a third cousin of my mother’s; her children Rui and Lara, and I, sit a step below.

Needless to say, formal relationships are not everything; it’s the level of friendship that counts. For instance, when the infant Maria Rita da Veiga, died of bronchopneumonia, a day prior to the arrival of a baby in the Gomes household, this new-born was baptised Rita Maria. The noble gesture speaks volumes of the oneness of spirit that proceeds from life built around shared values! In any case, a rarity in our day and age, this episode endeared the new Maria very especially to my mother who, aged 3½ years, had been confused and shaken by the disappearance of her immediate junior sibling.

There are, on the other hand, myriad incidents over which one has no control whatsoever; one gets to join the dots only much later. Consider my mother’s passing, at the age of 83½ years, precisely on Rita Maria’s eightieth birthday! Doesn’t this say something about the communion of saints that often goes unnoticed even by practising Catholics?

Life never ceases to amaze us. Prima Maria, despite her aches and pains, travelled to Canada, New Zealand and Australia – aching to connect with friends and relatives – whereas I’d failed to get in touch with her brother Heráclito in Porto. I’d thought of him, even in the midst of São João celebrations there, but it had remained just that – a thought… That I finally got to meet him, thirty years later, on Facebook, is another matter entirely! We now stand in awe of this gift from cyberspace.

My first – and last – lunch invitation to Prima Maria inevitably ended, but not before my mobile phone camera – sensing our connectedness – clicked away, trying to discover facial resemblances between kith and kin… And it was saudade once more…

Still a sunny afternoon, much like the one at Carcavelos, I drove Prima Maria to ‘A Pousada’, a pensão she was staying at, in the city’s charming São Tomé ward. We said our goodbyes, and I left. When I called up after a month, I got no answer… Heaven knows why!

Até sempre, Prima Maria!

Celebrating Braz and Jazz

"Raga Rock" was a much-deserved tribute to Goa-born Braz Gonsalves. Thanks to this presentation by Panjim-based Communicare Trust run by Nalini Elvino de Sousa, Goa got to sing paeans to a Jazzman who keeps a low profile after decades of showmanship in the Indian metros.

At the Kala Academy, on 14 June, I was charmed by the sight of a senior citizen at the entrance, welcoming guests with a gracious smile. Many passed him by, unsuspecting that he was Braz Gonsalves himself. For sure, many jazz aficionados have heard of the man and enjoyed his music; very few would have met him in person.

A few minutes later, the very same man wearing his trademark flat cap stole the show. At 86 years of age, he regaled a packed auditorium with his magical, golden saxophone. He was joined by his good ol’ boys: Louiz Banks (who formed the great Indo-Jazz Ensemble, with Braz); Karl Peters, India’s foremost bass guitarist, and drummer Lester Godinho, not forgetting his own, musically talented wife Yvonne ‘Chic Chocolate’ Vaz, daughter Sharon, son-in-law Darryl Rodrigues, and the youngest – and perhaps the most talented of them all – his grandson Jarryd Rodrigues. “Grandfather meets grandson,” boomed Banks, who also remarked that “the legacy of Braz Gonsalves is in the safe hands of his grandson Jarryd.” They made an amazing duo.

What a spectacular evening of jazz! And the music will play on, if the revelations on stage are anything to go by: Jazz pianist Jason Quadros, Portuguese-born soprano Maria Meireles, Anthony Fernandes (bass) and the ‘cool’ Coffee Cats comprising Ian de Noronha (keyboards, bass and melodica), Neil Fernandes (guitar and vocals), Jeshurun D’Cruz (drums), Jarryd Rodrigues (alto and soprano saxophone), Gretchen Barreto (vocals), Ajoy D’Silva (trumpet), and Lester D’Souza (tenor sax).

The music segment (vocals and instrumentals) was preceded by a musical skit in which sixteen children recreated the story of Braz Gonsalves’ life which began in Neurá-o-Grande, a village my ancestors hail from. And that was an added reason for me to celebrate Braz and Jazz!

Signs of our Times

Until 1961, official and commercial signage was, quite understandably, in Portuguese. Read more

Until 1961, official and commercial signage was, quite understandably, in Portuguese. Read more

Good Friday Procession in Panjim

The 3 o’clock, Good Friday service at the city church of the Immaculate Conception comprises a poignant Crucifixion tableau.

Soon thereafter, a procession of Senhor Morto (Dead Lord) on an andor (black canopied wooden platform carrying a life-size statue of Our Lord who died on the Cross) starts off, with a statue of Our Lady in trail. It wends its way through the main thoroughfares (the church square, a section of 18th June, Pissurlencar, past Azad Maidan), making a major halt to pray at the chapel formerly attached to the mansion of a Portuguese noble family. The cavalcade then proceeds via M. G. Road and Dr D. R. de Sousa, past the Garcia de Orta Garden, and up the church stairway.

The pious march takes approximately 90 minutes. It is animated by five decades of the Marian rosary recited over speakers fitted at several points; and by Lenten hymns sung by a choir to the accompaniment of a brass band. The circuit is marked by over ten descansos (halts). At these points, penitents, all of them de rigueur, in funereal attire, flock to the two statues. Members of other religious faiths also pay their respects; many watch in awe or stand at attention (I noticed a policeman saluting).

One such halt is at a quaint chapel traditionally called 'Capela de Dom Lourenço', located behind what is now the iconic Hotel Mandovi. In times past, the chapel was part of the manor belonging to Dom Lourenço de Noronha, a Portuguese nobleman, who had acquired a large estate in the then incipient city centre. After the palatial mansion was razed, the chapel was handed over to the care and possession of the city church. Alas, the venerable structure is in a state of disrepair.

On the said route, two Hindu families (Caculó and Neurencar) traditionally offer garlands. Businesses brighten up their establishments, or simply light candles and burn incense on the adjoining pavements.

In a coda to the baroque event is a sermon (Sermão da Soledade de Maria) at a stair landing: here, from a balcony that serves as a makeshift pulpit, a priest extols the virtues of Mary and highlights her present solitude. The congregation listens in silence even while vehicle noises spoil the ambience.

The statues return to the church for final veneration. By 8 o’clock, they call it a night!

Latter-day Lessons from Lent

A very important person who passed away recently is reported to have reflected profoundly on life and death, on his sick bed. Some others dismiss the story as a sham. At any rate, as the Italians say, si non è vero, è ben trovato – even if it’s not true, it’s well said. Reflections on the mystery of life and death hold important lessons for the human soul.

As Christians, we should be concerned about the life we lead, for upon that will depend our fate in the afterlife. It’s futile even for a churchman to bend over backwards to “save” a departed soul whose fate is practically sealed; and no amount of adulation can change their post-history. It is equally absurd to try and “modify” the image they’d carved for themselves. In short, it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of the needle than for history to be rewritten convincingly and abidingly by PR men. Truth always prevails.

Lent is an apt time to reflect on our personal history and on meta-history. The season reminds us that we are dust and to dust we will return; it points to our impermanence and to the limited time at our command. But, alas, as Helen Keller notes, “Most of us, however, take life for granted. We know that one day we must die, but usually we picture that day as far in the future. When we are in buoyant health, death is all but unimaginable. We seldom think of it. The days stretch out in an endless vista. So we go about our petty tasks, hardly aware of our listless attitude toward life.”

It is undeniable that each day brings us closer to death; then, why not prepare for it while it’s time! There should be no regrets when the hour strikes. Étienne de Grellet says very evocatively: “I shall pass this way but once; any good that I can do or any kindness I can show to any human being, let me do it now. Let me not defer nor neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again.” Truly, if we have lived with loving kindness, at the end of our earthly journey we will not fret about how history will remember us. In the memorable words of King Dom Pedro of Brazil, we will die in peace, “serenely awaiting the justice of God in the voice of history”.

But isn’t all this easier said than done? Yes; as frail human beings, we’re prone to fail. Hence, the accent should be on mending our ways and getting back on track. On the very first day of Lent, the Holy Scripture counsels us: “Rend your hearts and not your garments” (Joel 2:12). It’s a clear invitation to look inside ourselves and pluck out the evil lurking there. A time-tested prescription for a change of heart is prayer, fasting and alms-giving, provided we don’t practise our piety before fellow humans in order to be seen by them; or look dismal when we fast, like the hypocrites do; and, when giving alms, don’t proclaim it from the rooftops.

But that’s not all. In our Information Age, we might well summon up another pertinent Biblical prescription: “Let what you say be ‘yes, yes’ or ‘no, no’” (Matt. 5:37) This Biblical instruction rounds it up for our social media-savvy generation for whom praying, fasting and giving alms may not be an issue at all but taking a position may feel politically incorrect. For instance, a Christian who has had the impudence to refer to the sufferings of a politico, a mere mortal, on a par with those of Christ may well have betrayed Christ for thirty pieces of silver.

Steve Jobs, the man who hyped the Apple bite in the digital age, is also credited with a soulful quote recorded in his last days. He is said to have dubbed the modern, consumerist individual a “twisted being”. This is nothing new; it comes across as a newfound truth only because a latter-day ‘saint’ uttered it. The more important point to take in is that we shouldn’t leave plain truths such as these to startle us at the eleventh hour, when all along we’d learnt that our real treasure lies in Heaven.

We Christians who have gone through Lent year after year should have known better. Our catechesis should have set us thinking not only about life but about the afterlife as well. All things considered, Death lets us appreciate the meaning and purpose of Life – and this is perhaps one of the most important lessons we can draw from Lent.

First published in Renovação, 1-15 April 2019

and in The Stella Maris Bulletin, Lent 2019

Santos Passos in Panjim

The ceremonies of the Santos Passos (‘Holy Steps’, in Portuguese) – a representation of the holy steps of Christ’s Passion – date back to the early days of Christianity in Goa.

While the Holy Week services comprise the most intense moments of the Lenten observances, many churches spread them out over the 40 days of Lent.

At the church of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception, Panjim, a huge black screen is put up every year, on the first Sunday of Lent, at the archway leading to the chancel. As a little child, I was overawed but also curious to know from my Dad the meaning of the Latin expression inscribed very high up: “O mors, ero mors tua” means "Oh death, I will be your death".

Only much later, I got to appreciate John Donne’s poem, “Death, be not proud”, which ends with the line “Death, thou shalt die”. The words are from Hosea 13: 14.

Similarly, in John 11: 25-26, Jesus said, “I am the Resurrection and the Life; he who believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and whoever lives and believes in me shall never die.”

Inside the chancel of the Panjim city Church of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception, or say, behind the black curtain, the tableau changes every Sunday. Here are scenes of the first four Sundays of Lent.

- The Agony in the Garden 2. Jesus is condemned by Pilate 3. The Flaggelation 4. The Crowning with thorns 5. Condemnation by Pilate

The sixth Sunday of Lent is observed as Palm Sunday, alternatively called Passion Sunday. At this church, the scene is festive in the morning. By afternoon, the mood changes. After the evening Mass, the tableau portrayed is that of Jesus carrying the Cross. At other churches in Goa, this tradition of this tableau could be different. In fact, old parish churches in North, Central and South Goa have other peculiar traditions in this regard.

The larger-than-life size statue follows a procession of the faithful, down the zigzag stairs of the city church. The procession wends its way through the city streets, much like the procession on Good Friday, and returns to the church by Angelus time.

The Migrant

Short Story by Maria do Céu Barreto, originally written in Portuguese as "O Migrante". Translated by Óscar de Noronha, in Under the Mango Tree: Stories Stories from Goa © Fundação Oriente (Goa).

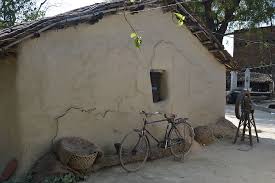

Vinod just couldn’t sleep. He tossed and turned in his bed and lay on his back again, just unable to doze off. He thought it better to keep his eyes open and treasure in his heart the little room he shared with his brothers, all of them younger than him. Through the gaps, the faint light of dawn was already visible inside the hut. He knew it was time to be on his feet yet kept lazing in his straw bed for a few minutes, thinking about his impending adventure.

What would Goa, where he was going to hunt for a job, be like? He was told by his country-cousins there that the land was bathed by the sea and its blue waters mirrored the clouds. There were long, seemingly endless, beaches of white sand. He rejoiced at the thought that it must be a very beautiful location indeed. He had seen the sea in the movies; now he would get to soak in its waters.

But then, he wasn’t going to Goa for its beauty. A job, however modest, is what he was looking for. He was gutsy and painstaking; work never intimidated him. Even as a little boy he had helped out in the fields. His father had tried to make sure his children would have a decent future; he had taken a bank loan and spent it all on those fields. But alas, the soil had been ungrateful; the gods did not help, despite the family puja every morning. The hot sun had burnt up all the plantations that he had seen grow. The rain gods had abandoned them. Only wealthy farmers had managed to live through the drought: they had the money for irrigation and to buy electric pumps to draw groundwater. Debts were mounting with every passing month, and one day when he came home, he found his father's body hanging from the ceiling. Unable to pay off the loan, he had committed suicide, like many other peasants in despair.

But then, he wasn’t going to Goa for its beauty. A job, however modest, is what he was looking for. He was gutsy and painstaking; work never intimidated him. Even as a little boy he had helped out in the fields. His father had tried to make sure his children would have a decent future; he had taken a bank loan and spent it all on those fields. But alas, the soil had been ungrateful; the gods did not help, despite the family puja every morning. The hot sun had burnt up all the plantations that he had seen grow. The rain gods had abandoned them. Only wealthy farmers had managed to live through the drought: they had the money for irrigation and to buy electric pumps to draw groundwater. Debts were mounting with every passing month, and one day when he came home, he found his father's body hanging from the ceiling. Unable to pay off the loan, he had committed suicide, like many other peasants in despair.

Vinod rose from his straw bed resolutely. He sat in the doorway to take in the morning air. He looked around. It was all arid. There was no other way out; he had to set off, to help his mother support the little ones, who were still asleep. The school was two kilometres away and they walked to and fro every day. Poor little chaps! Mother tried to persuade him to stay on. She needed him; it would be hard to bear it all alone. He put across his point of view in the best way he could, asking her to pray to the gods as she always did, without ceasing. And then, no more hesitation; his fate was sealed. But today he had still to fetch water from the well – his last chance to help out. With the little liquid left over from the previous days, he had a wash and, as usual, went to the bushes to answer Nature’s call. Toilets were a rare sight in the rural set-up. All governments had promised to build lavatories; those were only election campaign promises, forgotten as soon as the aspirants rose to power.

It was still very early in the morning, yet he wasn’t among the first ones to turn up at the well. There was already a queue for men and another for women. The menfolk usually drew the water and the women headed home with those pots held on their heads. Vinod was glad to see this line-up of women draped in multihued saris; they talked, giggled and looked askance at the boys. Lakshimi was there too. She had captured his heart and, by the looks she gave, his passion for her seemed to be reciprocated. How good it would feel to be back from Goa with money and to marry her! He had heard of many such success stories. He too would do well; he sensed success from deep within his soul.

It was still very early in the morning, yet he wasn’t among the first ones to turn up at the well. There was already a queue for men and another for women. The menfolk usually drew the water and the women headed home with those pots held on their heads. Vinod was glad to see this line-up of women draped in multihued saris; they talked, giggled and looked askance at the boys. Lakshimi was there too. She had captured his heart and, by the looks she gave, his passion for her seemed to be reciprocated. How good it would feel to be back from Goa with money and to marry her! He had heard of many such success stories. He too would do well; he sensed success from deep within his soul.

Back from the well, he saw his mother preparing breakfast at the firewood stove. She handed him a plate of roti and bhaji. He ate every bit, for he couldn’t say when his next meal would be. By now his siblings had woken up and were gearing up for school. Vinod thought of taking the eldest one with him to Goa one day, and then maybe the whole family! At construction sites there was always employment for everyone.

The train was due to leave at noon, and it would be two hours before he got to the station. He thought it better to start out before he had a change of mind. He had written to some of his village friends in Goa but hadn’t heard from them. He hoped at least one of them would pick him up from the station; it would be a relief if they got him accommodation, even if only for a week. His mother handed him whatever she had saved up for emergencies – a thousand rupees, quite a fortune, he thought. He tucked it away, picked up his suitcase, and humbly kissing his mother’s feet bid her farewell.

“God be with you, my son,” said his mother, embracing him. “Krishna will protect you.”

He couldn’t pluck up his courage to hug his siblings, who had started to cry. He patted them on the head and left for the station. He turned round before the last bend of the road: his mother and brothers were there waving at him. He paused for a moment and waved back. He was all alone now.

Vinod heard the whistle in the distance. The train had arrived, a little late as usual. The passengers stood where they thought their wagons would stop and were ready to pick up their suitcases. Travelling as he did, third class, Vinod had no reserved seat. He had to be in readiness, too, as it would now turn quite messy with people jostling for the best of places. As soon as the train halted, he picked his suitcase and dashed off to grab a good seat, and grab one he did. He placed his luggage on the rack and stretched his legs. He was very tired. Lack of sleep, anxiety, tension... Now he was sure to drift off. A few minutes after the train was in motion and had gathered speed, Vinod leaned on the headrest and shut his eyes.

He could not say how long it had been – maybe all night and a good part of the day – but when he woke up he found the landscape had changed. He tried to strike up a conversation with his fellow passengers.

“Have we reached?” he asked a young man who was going to Goa, or so he thought.

“Not yet. It’s still a little too early. We will get there by evening,” said the young man.

He wished to ask him a few more questions about Goa but noticed that he had dozed off. With a few more hours to go, he thought of walking up and down the corridor but feared for his seat. Patience! He would have to remain seated there throughout. He noticed some passengers preparing to eat their home-packed breakfast and, famished as he was, avoided looking at the foodstuff. Just then, a co-passenger invited him to share his breakfast, an offer he gladly accepted.

What a long journey it was! He closed his eyes again, knowing well he would not get even a wink of sleep amid the bustle of hawkers. The train had halted at a station and the peddlers were crying their wares – food, fruits, artefacts, and other items. They did everything to draw the attention of the passengers and win them over. Vinod smiled. He hoped to have Lakshimi by his side on his next trip. A slim and pretty girl she was, whose long hair, charcoal-black eyes and tanned skin made his heart stop. He had not bid her goodbye, for in the village boys seldom talked to girls without their parents' permission. And badly off as he was, they would ignore him. But everything would change when he returned with his pockets stuffed with cash. Where would he celebrate his marriage? Back at his native place for sure, in keeping with tradition. All expenses would be borne by the bride's parents. He would not ask for a dowry; he knew that her parents did not have the means and he had no intention to get them into debt, like many families did…. But would she wait for him until he came back?

Vinod fell asleep, lulled by these thoughts and unmindful of the noise. On waking up, all he saw was lush green countryside and water, water, water everywhere. There were lakes and rivers, and as the train carried on, he saw waterfalls too. He had never encountered anything like this before; he was sure it was Goa. Half an hour later he felt the train grind to a halt. The whistle blew; they were at Vasco da Gama, the port city of Goa.

Vinod fell asleep, lulled by these thoughts and unmindful of the noise. On waking up, all he saw was lush green countryside and water, water, water everywhere. There were lakes and rivers, and as the train carried on, he saw waterfalls too. He had never encountered anything like this before; he was sure it was Goa. Half an hour later he felt the train grind to a halt. The whistle blew; they were at Vasco da Gama, the port city of Goa.

A motley crowd welcomed their friends and relatives. Vinod felt his ears numbed by the numerous languages he heard: it was a real Babel. He even heard some words in his language! Was it his friends? He saw none; it was hard to locate people amidst the chatter. He let the other passengers exit first; he was not in a hurry. Then, all of a sudden, someone called out his name.

“Here, here we are!” Turning around he spotted Rama and Vishnu, his childhood friends. A strange joy seized his heart: he was no longer alone. They hugged him; they were thirsting for news from their land, family, friends, but Vinod, not in the mood for all that, promised to field questions a little later. He noticed that they looked very different, well dressed and cheerful as they were. Obviously, life had not treated them badly. He was happy for them.

“You’re staying with us tonight! Mother is waiting for you. Let’s see, if you like, you can even stay longer, until you get a job,” said Rama.

Vinod was thrilled. He did not know what to say.

“How are we going? Shall we take a rickshaw?” he asked.

“No, no, we’ll take our motorbikes.” Vinod was amazed. Their bikes? How did they manage to buy bikes? Questions and questions that would have to wait for answers…

On arriving at Rama’s house, Vinod found the pleasant aroma of food engaging his senses. It was a small house compared with the others around there, but it had electricity, piped water and even a gas stove – luxuries for people from poor, parched areas.

“Miss our land and our friends so much!” Rama exclaimed at the post-dinner chat. “No doubt it’s great out here, you know! Communities live in peace; no one interferes with you. Yet, it’s not the same as your own land. It’s a different culture; language and food are so different. To fit in, we’ve had to learn the local language, so much so that many of us speak better than the locals do!”

“And do the locals treat you well?” inquired Vinod.

“Well, they bear with us. They feel we are robbing them of their jobs and that in future they’ll be outnumbered by the migrant population. Maybe they will; I don’t know. However, they shouldn’t forget that we’ve helped them develop this state. We do all the hard work, so I think we’re a part of this land, although they don’t think so. They are proud of their half-Western culture and dub us ghanti and shower insults, which we pay no heed to… To make sure we do well, we must avoid squabbles.”

“And why can’t they get those jobs?” Vinod retorted.

“They can, except that they don’t want to work hard; they try to find jobs that won’t have them dirty their hands. The educated lot opt for the civil services or private company jobs. They think this fetches them better security and better respect. And those who don’t get such jobs or aren’t happy with what they have, simply migrate. I know families and families that have migrated.”

“They can, except that they don’t want to work hard; they try to find jobs that won’t have them dirty their hands. The educated lot opt for the civil services or private company jobs. They think this fetches them better security and better respect. And those who don’t get such jobs or aren’t happy with what they have, simply migrate. I know families and families that have migrated.”

“Where do they go?”

“Don’t ask! Maybe Dubai, England, Canada… I think there are Goans scattered around the world.”

“Are they happy?”

“Hard to say…. They earn better and enjoy a better quality of life… And who knows, maybe they even suffer humiliations like we do and are treated as second-class citizens.”

“And they sure miss their land,” observed Vinod.

“Of course, they do. They celebrate their respective village religious festivals, cook typical Goan dishes and even have exclusive Goan associations, where they meet regularly. You see, no one can forget their own little land.”

“So they are like us!” exclaimed Vinod.

“Yes; only that we are migrants and they are emigrants.

”Vinod was very tired and, by now, dying to go to bed, but the conversation was so interesting that he decided to linger.

“I don’t understand how you guys have all these things at home, and bikes too.”

“That wasn’t easy. We had to work hard. Of course, we have to also be in the politicians’ good books. At election time they grant whatever we ask for, in exchange for votes. The larger the family, the greater the bargaining power. For instance, you are alone and won’t get much, but if you tag your family along, you’ll get much more.”

“And how did you secure this place?”

“That wasn’t difficult. In fact, one has only to build a hut in some vacant space, live there and in time government legalises everything.”

“Incredible!” said Vinod. “I think coming here was the right thing to do. I’ll bring my family here as soon as I can.”

Just then they overheard some commotion outside. “What’s that?” said Vinod. “Who’s fighting?”

“Not to worry! That’s Vishnu; he drinks every night and creates a racket in the neighbourhood. He spends all his earnings on drinks. He has three children, and, to support the family, his poor wife works at several households. This is a real hazard in Goa. Alcohol and drugs are easily available. There’s a bar every few hundred metres. That’s a great temptation. Make sure you don’t fall into this trap, for then it’s tough to get out of it. We’ve come here to make money and have to focus on that.”

“Rama, thanks for the warmth and advice… I won’t do any such thing. I’ve suffered enough back home; I’ve seen misfortunes caused by the lack of money. The first thing I’ll do now is look for a job.”

“I’ll help you if you like. I know the builder of the nearby constructions. If I recommend your name, he’ll find you a job.”

“Yes, please do.”

Vinod thanked him once more and went off to bed. The morrow would be another day. So far so good! The future was in God’s hands. He smiled and fell asleep with these thoughts. Was he dreaming of Lakshimi?

Glossary

Roti: An Indian unleavened flatbread made from wholewheat flour and water that is combined into a dough. It is rolled out and cooked on a griddle over a flame.

Bhaji: A vegetable preparation

Puja: Prayers

Ghanti: Lit. From across the ghats. Coll. Outsider. A derogatory term directed at people, especially non-Goans who come to Goa, whether they are from across the ghats or not.

Relics of St Anthony in Goa

The pilgrimage of the holy Relics of St Anthony covers India from 19 February to 20 March this year. This is being held to mark St Padre Pio’s 100 years of stigmata, the 50th anniversary of his death as well as that of the Capuchin presence at St Pio Friary, Navelim.

It may be noted that St Anthony, born Fernando Martins de Bulhões (1195-1213), in Lisbon, Portugal, worked and died a Franciscan friar in Padua, Italy. Hence the respective countries know him alternatively as 'St Anthony of Lisbon' and 'St Anthony of Padua'. This is perfectly legitimate for, in the Catholic hagiological tradition, a saint's place of birth, work and death are equal in importance.

St Anthony was noted for his powerful preaching, expert knowledge of Scripture, and undying love and devotion to the poor and the sick. He was one of the most quickly canonized saints in church history. He is a Doctor of the Church and regarded as patron saint of lost things.

In the year 1525, the religious Order of the Franciscans to which St Anthony belonged had a major offshoot in the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (Latin: Ordo Fratrum Minorum Capuccinorum; post-nominal abbreviation, O.F.M.Cap.)

Fast forward to the twentieth century. Francesco Forgione (1887-1968) joined the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin. He assumed the name 'Pio' (Pius, in Italian) and later came to be known as Pio of Pietrelcina, his birthplace. A mystic, he eventually became famous for exhibiting stigmata (that is, appearance of bodily wounds, scars and pain in locations corresponding to the crucifixion wounds of Jesus Christ, such as the hands, wrists and feet). He was beatified (in 1999) and canonized (in 2002) by Pope John Paul II. A religious sanctuary takes his name at San Giovanni Rotondo, province of Foggia, Italy.

The present pilgrimage of the relics of the Saint marks an important milestone in the history of the Religious Order. It equally helps keep their use in perspective and promote the faith of the people. As St Jerome wrote in his 'Letter to Riparius', “We do not worship, we do not adore, for fear that we should bow down to the creature rather than to the Creator, but we venerate the relics of the martyrs in order the better to adore Him whose martyrs they are.”

This is something that in our jet age some may find quite strange. But then, don't we treasure objects that once belonged to a loved one – be it a piece of clothing or even a lock of hair? And don't museums scout for and showcase items that belonged to the rich and famous - be it a writing pen or a gun or even a bullet that might have killed the person concerned? Similarly, Catholic believers treasure the relics of saints.

At the church of the Alverno Friary, Monte de Guirim, my family and I were among thousands venerating the fragment of petrified flesh embedded at the heart of a golden reliquary bust of St Anthony. And when a tiny silver reliquary caught our eye, they informed us that it contained the Saint’s smallest rib bone, otherwise designated for veneration only by the sick. Whereupon we kissed the reliquary most reverently.

At the church of the Alverno Friary, Monte de Guirim, my family and I were among thousands venerating the fragment of petrified flesh embedded at the heart of a golden reliquary bust of St Anthony. And when a tiny silver reliquary caught our eye, they informed us that it contained the Saint’s smallest rib bone, otherwise designated for veneration only by the sick. Whereupon we kissed the reliquary most reverently.

The Alverno Friars exhorted pilgrims to pray ardently even as an impromptu procession wended its way to the hilltop. Most people chose to listen to and sing hymns playing on the public address system, as a form of prayer. It took us a good 1½ hours to inch forward to the chapel housing the Relics. These will spend the second half of Saturday and the whole of Sunday, 4 March, at the Navelim friary.

Before we close, here's a nugget of information: the Friary is named after a similar house of the same Order, situated on Mount Alverno, Ontario. Although education is the main activity of the friars, they are also engaged in preaching the Word of God, spiritual assistance, other pastoral ministry in the chapels and parishes nearby. The friars are also chaplains to several convents in the neighbourhood. The Friars run a social welfare centre each at Guirim and Sangolda.

My family and I loved and felt blessed by the experience of resting our eyes on the Relics of St Anthony!

Who will do the kator re bhaji?

‘Kator re bhaji’, meaning ‘Be bold; go ahead and do it!’, is not just another idiomatic expression in Konkani; it went down in history after a Goan, Caetano Vitorino de Faria of Colvale, Bardez, was heard prodding his son, Abbot José Custódio, who was with his nerves on edge at the pulpit in the royal chapel in Lisbon. Much later, Faria Jr., who studied the power of suggestion, came to be regarded as the ‘Father of Hypnotism’.

Meanwhile, they say that Faria Sr. and a few others had plotted to oust the Portuguese and establish a republic in Goa, in 1787. Had they succeeded, Goa would probably have seen the establishment of a republican regime two years before the French republic came about with its motto Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité…. (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity).

Today is the 26th of January. How does the common man regard this day? As a holiday, of course! Others look at it as the Republic Day of India, even while unsure of what a republic really means! So let us see what it is, and how it is different from a democracy pure and simple….

A democracy is people’s rule, or – in Abraham Lincoln’s memorable words – “a government of the people, by the people and for the people”. A republic is a “rule by elected officials” (as opposed to hereditary rulers).

Well, all republics are democracies, but not all democracies are republics. For example, a ‘direct’ or ‘pure’ democracy (that in which the people vote directly on every issue) is not a republic; whereas a ‘representative’ democracy (one in which the people elect representatives to study and vote on issues on their behalf) is another name for a republic.

Where does India fit in all this? India gained independence from Britain on 15th August 1947; but few may know that the King of England continued to be at the helm, thanks to the Government of India Act of 1935 that remained in force for some time to come! Why? Simply because Free India still did not have a constitution! So, on 28th August 1947, a committee was appointed, with Dr Ambedkar as chairman, to draft a constitution. This became effective from the 26th day of January, 1950.

Thus, whereas Independence Day celebrates India’s freedom from British rule, Republic Day celebrates India’s constitution. Interestingly, 26th January was chosen as the D-day because, twenty years earlier, on that very day, the freedom movement spearheaded by the Indian National Congress had declared Purna Swaraj (complete freedom) as its objective. The 26th of January was dedicated to fully honouring that freedom, with the rule of law.

The Preamble of the Indian Constitution states that India is, among other things, a “democratic republic”. Thank God, there are internal checks and balances that prevent it from turning into a dictatorship. However, some would have it that India is indeed a democracy, a plutocracy, a kleptocracy and a mobocracy, all rolled into one! If that is so, who is responsible for this state of affairs? You and I! And thanks to its economic and technological progress, India today is a Netocracy as well. This is the great new reality. Remember, social networking is said to have clinched Obama’s recent victory; similar political trends are noticeable in the Indian context as well.

In 1950, India’s many monarchs gave in to the supremacy of the people. Democracy shaped in the form of a republic became the spirit of India. But the moot question is: Where do we, the people, stand today? Have we really grown and blossomed as a republic?

The republican system is not new to India. Our villages with their ganvkari were indeed little republics, each of them self-sufficient in goods and services. Under the Portuguese they came to be preserved as Comunidades, whereas in British India it is unfortunate that the system vanished into thin air.

Where do the precious values of those institutions stand today, in our fast-moving world steeped in materialism and consumerism? Today, India will flaunt her might at the Parade in New Delhi; but has the common man in India any might to parade? Can we in all honesty celebrate the sovereignty of the people of India? Aren’t the people usually taken for granted?

While we thank the Almighty for the positives that the country has seen, including its proud position in the comity of nations; it is also important to look at the abysmal lows that we have touched: the newspapers are brimming with news that makes us hang our heads in shame.... So, really, the speechifying must stop – I must stop – and we must ensure that we work concretely towards refreshing changes in the country. And to see that the Republic of India truly turns around, it is for you to bell the cat; it is for you, the younger citizens, to do your bit of the kator re bhaji!

(Republic Day speech, 2013, Prerana, Vol. XV, 2012-17)