Sonia - The Fado's New Fate

Sonia Shirsat is the Fado’s Lady Fate in Goa. On Valentine’s Day she swore her love for Portugal’s iconic melody. That the song has come to stay became obvious from the near-full Dinanath Mangueshkar auditorium that lapped up every bit of Mundo Fado II, Sonia’s first solo show on home turf.

Sonia’s voice is extremely well suited to the fado. Her talent first became evident at the ‘Vem Cantar’ contest (2002), through her superb rendering of Madre Deus’ ‘O Pastor’. Before long, ‘Barco Negro’’ sung by her also became a people’s favourite. And this time, a bright new ship – ‘M. V. Mundo Fado’, if you like! – dropped anchor in Panjim, from where it will again sail the Seven Seas.

Impressive is the line-up of fado greats that Sonia has performed with over the years. But more fulfilling must have been her own first solo concert, Mundo Fado, held in 2008, at Museu do Oriente, close to Alcântara docks, by the Tagus. She sang to a packed house, with guest artistes including Mestre António Chaínho, Manuel Leão, and Casa de Goa’s musical troupe, Ekvat!

Notice the poetry of that fabulous setting: the Orient, harking back to Goa; the proverbial waterfront, where the Fado originated amidst a sailor community; and the Tagus, from where all those intrepid ships once sailed “o’er seas hitherto not navigated… to seek out new parts of the world”….

So it was at Alcântara (‘the bridge’, in Arabic) that Sonia crafted her musical bridge with the fado world. Climbing onto the international stage is no mean task, especially for one not fully born into the genre. Sonia chose to cultivate it, chaperoned by her Lusophile mother Maria Alice Pinho, who belongs to a Goan generation raised on Portuguese music.

Mundo Fado II started off with an evocative instrumental medley by Sonia’s main accompanists, Flávio Teixeira Cardoso (Portuguese Guitar) and Pedro Miguel Soares Marreiros (Spanish Guitar) from Portugal. While they were at it, in walked Sonia draped in a designer gown and shawl. The backdrop was a quiet, understated, white with colour focus lights. Her first song was ‘Cansaço’ (‘Weariness’)… but needless to say both audience and artiste were zestful until the end!

There was a happy mix of familiar and not-so-familiar numbers. ‘Alfama’ (a tribute to Hotel Cidade de Goa’s restaurant of the same name where she is the lead artiste at the monthly ‘Noite de Fado’) was followed by ‘Amor de Mel’, Fado das Horas’, ‘Tive um Coração’, ‘Meu Amor Marinheiro’ and ‘Zanguei-me com o meu Amor’, among others.

Sonia’s show was marked by measured stylistic innovation. It featured the tabla (Mayuresh Dattaram Vasta), the flute (Marwino António da Costa) and the dhol (Santosh Sawant). And in a style all her own, the vocalist had none of that over-the-top emotionality of the Portuguese fadistas, nor did the tempo quicken as the show progressed; but she sang with passion, offering personal and historical snippets in her announcements.

Sonia infused the fado with new blood, giving the genre a fresh lease of life, and perhaps scope for another to emerge (in a Goan tradition of give and take, which people of good will must endorse). ‘Rua do Capelão’, a ‘modern fado Severa’, with flute and guitars, was a tribute to Maria Severa, 19th century Portugal’s best-known fadista. The popular ‘Cartas de Amor’ was backed by flute, tabla and Spanish guitar; and ‘Ave Maria Fadista’ by tabla and the guitars. It was most fascinating to see the Indian instrumentalists gel with their Portuguese counterparts in ‘Barco Negro’. The latter also took to ‘Doreachea Lharari’ and ‘Adeus Korcho Vellu Pavlo’ as fish to water.

Sonia hailed the mandó as ‘Goa’s fado’! And curiously, hiding behind the Konkani title of our best-known farewell song were Portuguese lyrics – the labour of love of a suave Goa enthusiast Manuel Bobone. The ensuing musical dialogue symbolised a confluence of the past and the future; and its melody is an apt signature tune for Sonia’s Luso-Goan musical experiment.

Mundo Fado II unwittingly commemorated the centenary of the modern fado, first recorded in 1910. And, putting behind its nearly five-decade long hiatus in Goa, Sonia gave a clarion call to young fado singers Danika da Silva Pereira, Manuela Lobo and Efigénia de Santana Miranda to rise to the occasion. She also expressed her camaraderie by inviting guest artistes Carlos Manuel Meneses and Allan Abreu (both Spanish Guitar), Daryl Coelho (Mandolin) and Franz Schubert Cotta (Portuguese Guitar) to be on stage with her. And early in the show, she recalled the musical moments shared with Orlando de Noronha and Dinesh K., both of whom couldn’t make it that day….

That’s ‘Team Sonia’ for you, poised to carve out a brilliant new fate for the Fado in Goa!

(Herald, Goa’s Heartbeat, 23 Mar 2011)

Surreal Tête-à-Tête

It was one of those nights when at first it looks as if nothing out of the ordinary is going to happen; but then, when one is already dead to the world – and can’t possibly expect anything to happen – almost everything happens.

Yes, in a dream anything can happen, triggered by a poignant scene witnessed earlier in the day, a gripping tale told or heard, or by interface of nostalgia and anticipation. For, as Eliot says in Four Quartets, “Time present and time past Are both perhaps present in time future, And time future contained in time past.”

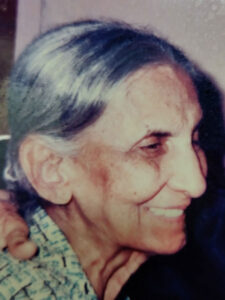

The tête-à-tête I had on the second night of the New Year gave me the sense that “all time is eternally present, All time is unredeemable.” Time past and time present did get inextricably mixed when I was greeted by my grandmother Leonor (1900-1992), of happy and adorable memory.

While in real life it was grandma who waited for reports from the world of light, now it was my turn to seek news from beyond the tomb… about the Light of the World.

I was helping out at the funeral of a close relative when suddenly my Avó took centre stage. This was uncharacteristic of her, as like Mary in the Magnificat she always kept a low profile. In a coffin she lay – moved, quite oddly, to a busy commercial establishment at the Panjim church square, which was once called Largo das Flores, the Flower Square. But there were no flowers anywhere, no candles, no voices of mourning – only the din of the madding crowd and the motors outside.

It wasn’t an upsetting sight to behold, because the old lady herself was relaxed, seemingly waiting for a visitor to arrive. She had closed her eyes: I reckon she found no sense in doing otherwise after glaucoma had struck her blind in the last four years of her life.

My Brazilian friend Aluísio used to say, “When God sends you an illness, be sure He will also make the bed.” So it was for Avó, who had been blessed with an extra sense. She could literally feel the presence of a person in the room, although this time around she had mistaken me for Fernando, her firstborn and my father standing by her cradle. The cause of the confusion? Maybe my voice which sixteen years down the line has, so they say, grown closer to my father’s. But soon she said, radiantly, “Ah! It’s you, Oscar!”

The exclamation caused a gush of memories, like her grandchildren whom she always welcomed home – me in particular, every single day, after that gruelling journey to Quepem and back.

“Absolutely delighted to see you, Avó,” said I, feeling that sixteen years had telescoped into a day. While in real life it was grandma who waited for reports from the world of light, now it was my turn to seek news from beyond the tomb… about the Light of the World. I just could not wait and so, like a stuttering rifle’s rapid rattle, I fired a few questions:

“Avó, does God exist? Have you met Him? Spoken to Him? Where is He?”

That is when I noticed her standing upright. There was behind her a glass door as clear as crystal and sporting a red-and-yellow horizontal band; which opened onto the footpath. In stoic silence, with her eyes still shut and her smile withdrawn, she faced my inquiry. I thought briefly that my references to the divine had been brash, and was going to apologise; but the very next instant, perhaps misreading her stillness as endorsement of my momentary unbelief, I prodded her with more questions:

“Where is He? Up there, or down here? Were you there?”

An inquisitorial Pilate got no answers from Jesus, did he? The same here; and, in addition, I was woken up. In vain did I try to recover that magical ambience of suspended consciousness, by burying my face deep in my pillow! There was also that enigmatic lady in a green sari, who was babbling a few nothings in her bid to liaise between my grandmother and me; but again, to no avail.

Fled was that vision, the saving grace being the sound of music about my ears: later I identified it as “Jezu, Ballka Pritichea” (‘Our Dear Child Jesus’) – a solemn polyphonic composition by our very own Fr. Vasco do Rego. (On waking up I was divided between that hymn and Fr Peter Cardozo's vivacious "Zoi Jezu, Amcheá Raza", meaning 'Hail, O Christ, Our King!'')

By now the sparrows outside had begun their chirpy melody, while the inside of me thumped like a drum. Hailing that hymn as a sweet reply to my impatient musings, I realised that it was nearing the Angelus, a moment very close to Avó’s heart. I was gradually coming to terms with my intimate reality, confident that it had disturbed no one, but soon thereafter, pretty shaken up was I when my firstborn, Fernando Jr., waking up as usual at seven o’clock, asked quite matter-of-factly, “Papa, whose funeral did you attend yesterday?”

(Herald, 9 February 2009)

The Place to Celebrate Christmas

Have you ever wondered about the best place to celebrate Christmas?

In my growing years I would often hear overseas relatives sing the praises of Christmas celebrations in Europe; it made me feel that something was amiss in Goa. And last Sunday, Zelia, a plump and contented lady, sixty-plus, living in a suburb of Lisbon, boomed in the churchyard, ‘Here it doesn’t feel like Christmas at all. Back home, you will find shop windows decorated by now, and people rushing about their Christmas shopping.’

No feelings of inadequacy on my part this time round. If that is what she feels, so be it, I thought, and it took me back twenty years to my own reservations about Lent in the Portuguese capital. I remember saying then to Mario el mexicano, a university pal and churchgoer, ‘Back home, we have the Way of the Cross from our city church perched on a hillock to the Archbishop’s Palace on another hilltop. It’s unmistakable; it really makes one feel it is Lent.’

People are entitled to their individual feelings, aren’t they? And God can touch the core of our being in any situation we may be. Ours is not a rectilinear world; and like the heavenly bodies we can go in curves, yet reach the destination the Creator has planned for us. After all, whatever our weaknesses – to quote Yeats, the Irish bard – He who is wrapped in purple robes, with planets in His care, ha[s] pity even on the least of things asleep upon a chair….

But for our part it is better not to lose sight of the Ultimate Reality. At Christmas, the crib, the star, the tree and the lights – however beautiful; the carols – howsoever melodious; the sweets, no matter how delicious – and the little joys they all afford us – should not be an end in themselves.

Rather, our crib and star competitions could help us promote healthy relationships; our tall and intensely decorated trees, to gaze heavenward; the shiny decorative lights we display in our homes, to reflect the state of our souls; the carols we sing, to foster peace, goodwill and harmony among us mortals; and all the eats and drinks that we prepare could well be an expression of the profound joy and love we share with our family and friends.

And what shall we say about the ever-present Santa Claus and his gifts?

A few days ago, a young television journalist interviewing passers-by in the street came up to me, thundering with great expectation, ‘Sir, tell us what Santa Claus means to you and your children!’ And perhaps to her surprise, I said, nonchalantly, ‘Very little.’

Santa Claus means very little to me and my family. This is one institution that has almost become an end in itself – hardly a reminder of the good old St Nicholas, and of Jesus Christ, alas, none at all! Santa has not sanctified but altogether commercialized and secularized Christmas. How I wish Santa had not sought to turn this feast of extreme tenderness, extremely banal.

We cannot let the Christmas mystery turn banal. No doubt, Jesus was born in a humble stable, into a poor family. Simple shepherds were the first witnesses to this event. But – as the Catechism of the Catholic Church points out – ‘in this poverty heaven’s glory was made manifest.’ And the Church never tires of singing the glory of this night:

The Virgin today brings into the world the Eternal

And the earth offers a cave to the Inaccessible.

The Angels and shepherds praise him

And the magi advance with the star,

For you are born for us,

Little Child, God eternal!

This verse from Kontakion of Romanos the Melodist sums up that Mystery-in-swaddling-clothes. And, as the Catechism further remarks, ‘from the swaddling clothes of his birth to the vinegar of his Passion and the shroud of his Resurrection, everything in Jesus’ life was a sign of his mystery’ – a mystery that certainly calls for deep contemplation.

It is of supreme importance, particularly to contemporary man, to note that the Christmas mystery is richer than the richest of shop windows. And we needn’t go to the ends of the Earth to realize this: When we participate in the Mass this day, with a pure and contrite heart, we will come upon the experience like a benediction. Then we shall see that our hearts are the best Crib for the Little Child, God eternal, to be born in and also the best place to celebrate Christmas!

(Published as Editorial, The Stella Maris Bulletin, December 2008; and reprinted by Herald, 22 December 2008, and Renovação, 1-15 January 2009)

THE MAESTRO’S TOUCH

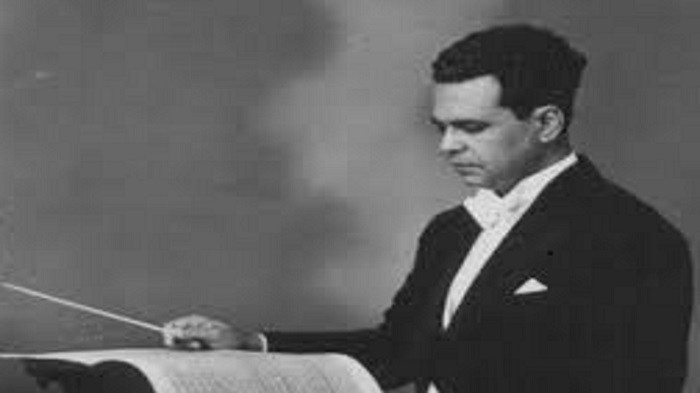

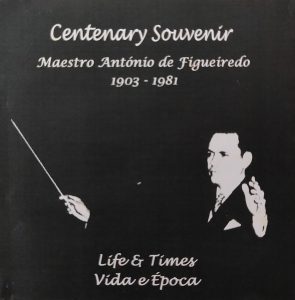

Three cheers to the first of our very own Von Trapps – on their comeback and creditable stage performance during the birth centenary celebrations of their patriarch António de Figueiredo. This Goan maestro was perhaps singly responsible for setting the Western musical scene in our land on a firm professional footing, way back in the mid-1950s. I heard he was quite a sensation in those days and exerted an important influence on the Goan people.

I heard he was quite a sensation in those days and exerted an important influence on the Goan people.

I vividly remember my parents recommending the Goa Philharmonic Choir and Symphony Orchestra, which was to perform under his baton at the Menezes Braganza hall, in 1973. It was a veritable feast for my senses as an eight year old, never mind the minimal acoustic conditions of the venue. The concert also proved to be the beginning of my love for western classical music, especially as a result of its many replays, possible for us as a family, thanks to my father who had taken the initiative to audio-record it on our spanking new Hitachi!

How I wish the local stations of All India Radio and Doordarshan had taped the proceedings of this birth centenary for the larger Goan family at home and abroad! And as a more eloquent public homage to the maestro, it would in the fitness of things to have Kala Academy’s open-air auditorium named after him who was the founder-director of the Academia de Música (now Kala Academy’s department of Western Music), and similarly, a prominent city and village street too; to have a bust of the maestro installed in the premises of the Kala Academy, scholarships instituted in his memory, and to entrust a musicologist with the job of writing a biography and putting together his musical works. The centenary CD released by his admirers is a step in the right direction, but only for starters!

How I wish the local stations of All India Radio and Doordarshan had taped the proceedings of this birth centenary for the larger Goan family at home and abroad! And as a more eloquent public homage to the maestro, it would in the fitness of things to have Kala Academy’s open-air auditorium named after him who was the founder-director of the Academia de Música (now Kala Academy’s department of Western Music), and similarly, a prominent city and village street too; to have a bust of the maestro installed in the premises of the Kala Academy, scholarships instituted in his memory, and to entrust a musicologist with the job of writing a biography and putting together his musical works. The centenary CD released by his admirers is a step in the right direction, but only for starters!

The concert also proved to be the beginning of my love for western classical music, especially as a result of its many replays, possible for us as a family, thanks to my father who had taken the initiative to audio-record it on our spanking new Hitachi!

(The Navhind Times, Panjim, 22 August 2003)

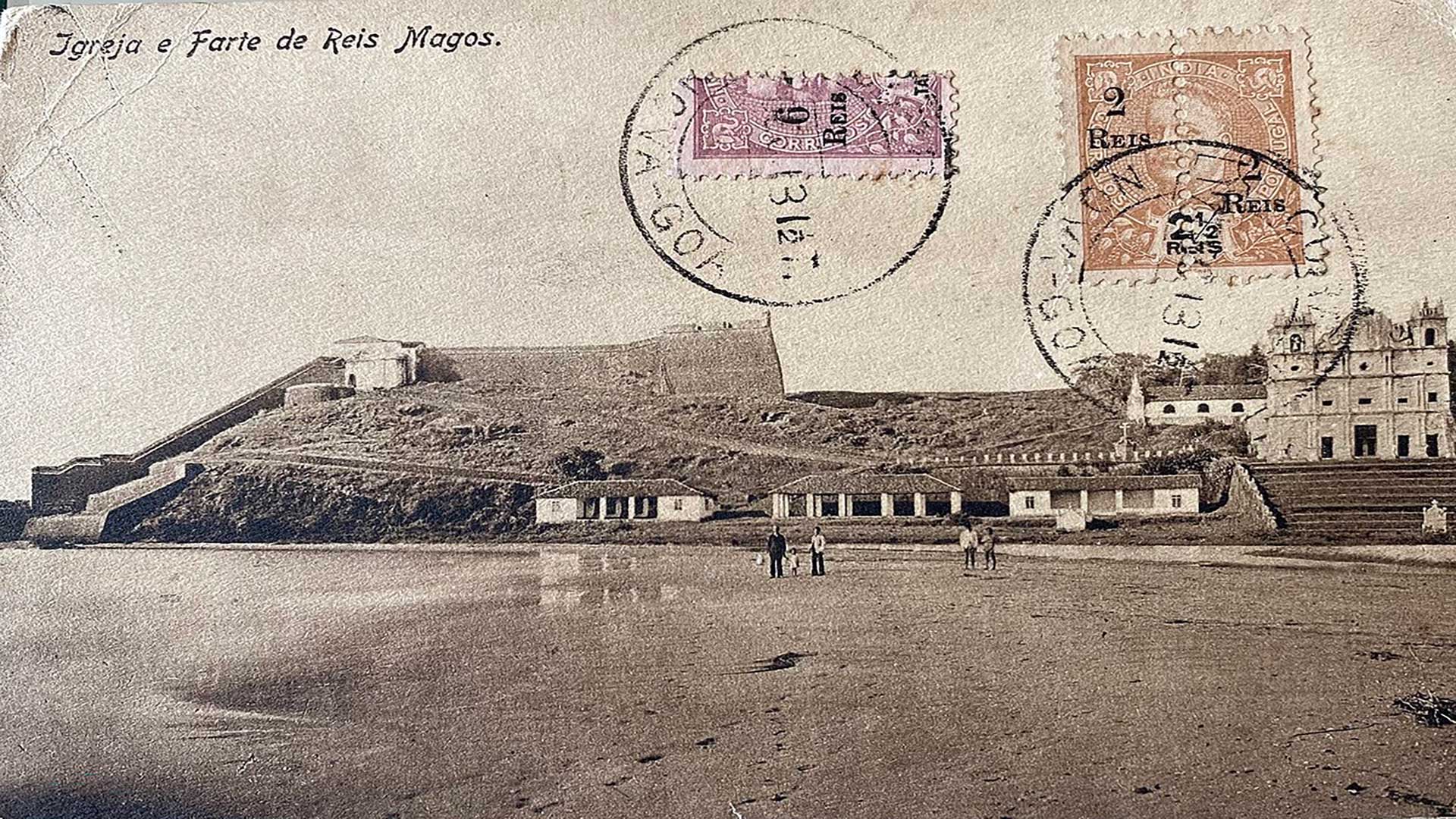

Fort and Church of Reis Magos

On the right bank of the Mandovi, facing Panjim's river front boulevard at Campal, stand a fort and church called Reis Magos (The Magi), landscaped by red rocks, yellow-green vegetation and a fishing village. The turreted walls and baroque façade in this chromatic setting come out soft in the morning rays, turn awesome at noon, and are a sight to behold when silhouetted by the setting sun or bathed by the moon.

Perched on the south-eastern edge of the Bardez tableland, the citadel was constructed in 1551, enlarged on different occasions, and finally re-erected in 1707. It is now X-shaped with two inner courtyards. Together with Gaspar Dias, its counterpart on the opposite shore, it was meant to provide the second line of defence for the capital should the enemy manage to sail past the Aguada and Cabo forts. Interestingly, the fort that acted as a minor jail until 1993 was where, over a century ago, Madhav Rao, the rajah of Sawantwadi stayed when on an official visit to Goa with a retinue of 1500 men, 1000 horses and 4 elephants.

A perennial nearby spring with abundant potable water catered to the fort; but to nourish the soldiery with "living water" the Franciscans erected a church alongside its walls in 1555. This three-storied edifice (the taluka's first), with its impressive light of steps, was part of their now extinct mission centre. Their college promoted Konkani studies, and produced eminent churchmen like Dom Matheus de Castro, Goa's first bishop. It was also there that both viceroys and bishops sojourned prior to assuming office upon their arrival in Goa, or after relinquishing it. Some of them lay buried within the church precincts; the walled parish graveyard nestling on an intermediate level between the church and the fort came much later.

This historic locale, called Verem, is now better known for its annual celebration of the feast of the Epiphany on 6 January. No viceroy, bishop or nobleman now attends; it is only three village boys in gala attire who still play the Magi. They descend from the ramparts (earlier they did it on horseback), carrying their precious gifts and the solemn Mass begins even amidst the din of the traditional fête outside. Only trinkets though they sold- and not gold, frankincense or myrrh in the tradition of the Magi the fair that was once worthy of the fort's enclosure has now become a roadside affair. But the joy it brings to all that throng to it! What form all these customs will take when the fort turns into a heritage hotel soon, only time will tell!

Banner: https://rb.gy/xjugos

First published in 'Heritage Point', Panjim Plus, 1-15 January 2002, p. 6

Yuletide Recollections

Solemnising the dogma of the Immaculate Conception at the city church (8 December) was a good spiritual preparation for Christmas just round the corner. The angelic music of the Salves at twilight prefigured the celestial choirs intoning "Gloria in Excelsis Deo" a fortnight later. Caroling house to house, late in the evening, was the order the season (the proceeds went to Mother Teresa's Asilo). City clubs like Nacional and Vasco da Gama organised carol singing competitions, balls and street dances. The household would be agog with the Crib, the Star and the Christmas Tree.

24th December: after the Midnight Mass, we used to head straight for the pillow to herald Pai-Natal (Christmas Father) in our sleep. We woke up the next morning, excited about the festa da família (family celebration) – more recently, a veritable family reunion at lunch or supper! We particularly relished the consoada (meaning, the season's sweets, in Goa) comprising traditional homemade delicacies that Avó (Grandmother) Leonor insisted on having for Christmas.

The days that followed, up to 6th January, feast day of the Reis Magos (the Magi, or Three Wise Kings) at Verem, saw Panjimites on their evening beat around the city. They invariably walked up to Timoteo's mechanised crib, or drove to Francisco Martins' at Ribandar. Other private houses and public squares used colourful lighting.

Once upon a time, that was my Christmas agenda. Much of it has gone but some of it has remained in the form of a musical reverie, thanks to Jim Reeves, my childhood star who still sings "Jingle Bells", "Silent Night", "Mary's Boy Child" and "White Christmas".

(First published in Panjim Plus, 16-31 December 2001)

The Fragrance of Carmel (Concl.)

Significance of the Carmelite way

There are many Carmelite Orders, both male and female, in the Catholic Church of the Roman and Eastern Rites. The original Carmelites were an Order founded on Mount Carmel, by Berthold, a Crusader from Calabria, about the year 1155 A.D. They constitute the Order of the Brothers of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Ordo Fratrum Beatissimæ Virginis Mariæ de Monte Carmelo, abbreviated O. Carm.) who were constrained to leave the area and settle in Europe.

There are many Carmelite Orders, both male and female, in the Catholic Church of the Roman and Eastern Rites. The original Carmelites were an Order founded on Mount Carmel, by Berthold, a Crusader from Calabria, about the year 1155 A.D. They constitute the Order of the Brothers of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Ordo Fratrum Beatissimæ Virginis Mariæ de Monte Carmelo, abbreviated O. Carm.) who were constrained to leave the area and settle in Europe.

Thereafter the Order underwent many reform movements, the most important one being the one initiated by Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross. They founded the Order of Discalced Carmelites (O.C.D.), also called Barefooted Carmelites, to differentiate them from their predecessors who were ‘calced’. There is also an Order of Cloistered Carmel nuns.

Interestingly, the Stella Maris Monastery presently on Mount Carmel in Palestine is considered the spiritual headquarters of the Carmelite Order.

The Carmelite charism is an important jewel in the Catholic crown. Here are some reasons why:

SPIRITUALITY: Centuries of Carmelite history shows us that longing and living for God is the essence of their spirituality. It is clear from the numerous exemplary lives of their confreres that it is indeed possible to encounter God very intimately. This is an experience attained through simplicity, detachment, contemplation, prayer and work, all of which produces an apostolic spirit, in many ways similar to the life led by Our Lady.

MODELS: The Carmelite Order has given several saints to the Catholic Church, among them mystic authors like Teresa of Ávila (1515-82) and John of the Cross (1542-91), who shine out as Doctors of the Church. Centuries later, Thérèse of Lisieux (1873-97, also known as Teresa of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face) whose highly influential model of sanctity marked by a simple and practical approach to the spiritual life also won her the title of Doctor of the Church.

Elsewhere in the world, the richness of the Carmelite spirituality was evidenced by Kuriakose Elias Chavara (1805-71), a Syro-Malabar priest of the Carmelites of Mary Immaculate (C.M.I), from Kerala, and by Edith Stein (1891-1942), a German Jewish philosopher who converted to Christianity and became a Discalced Carmelite nun.

LITERATURE: Several Carmelites have endowed us with the fruits of their study and contemplation, the chief among them being St Teresa of Ávila and St John of the Cross. To the former belong many poetical works and spiritual classics like The Way of Perfection and The Interior Castle, besides her engrossing autobiography; the latter author has to his credit poetic works like Spiritual Canticle and Dark Night of the Soul, and prose works like The Ascent of Mount Carmel, among others. Thérèse of Lisieux’s autobiography, The Story of a Soul, was published posthumously. In the monastery where she lived, Edith Stein was assigned the task of completing her autobiography, Life in a Jewish Family; she also wrote Finite and Eternal Being – An Ascent to the Meaning of Being and Science of the Cross, commenting on St John of the Cross and the Carmelite understanding of the depths of the soul.

MESSAGE TO THE WORLD: At the Apparitions in Fátima, whose full import the world is yet to understand, Our Lady of Mount Carmel appeared to Sister Lúcia holding the Brown Scapular. The famous visionary, who later became a Carmelite nun, stated that our Divine Mother wished everyone would wear it as a sign of their ‘consecration to her Immaculate Heart.’ For sure, the sacramental is a quiet and comforting reminder that Our Lady is always there for us.

There is therefore no doubt that we are in the presence of a prophetic Religious Order: The Carmelites!

The Fragrance of Carmel (Part II)

Pentecost, a red-letter day

According to a pious tradition, supported by the liturgy of the Church, on the day of Pentecost a group of men devoted to the holy prophets Elijah and Elisha embraced Christianity. They were disciples of St John the Baptist who had prepared them in view of the advent of the Saviour. They left Jerusalem for Mount Carmel and there they erected a sanctuary to the Virgin Mary, at the same place where Elijah had seen the Cloud. They called themselves Brothers of the Blessed Mary of the Mount Carmel.

According to a pious tradition, supported by the liturgy of the Church, on the day of Pentecost a group of men devoted to the holy prophets Elijah and Elisha embraced Christianity. They were disciples of St John the Baptist who had prepared them in view of the advent of the Saviour. They left Jerusalem for Mount Carmel and there they erected a sanctuary to the Virgin Mary, at the same place where Elijah had seen the Cloud. They called themselves Brothers of the Blessed Mary of the Mount Carmel.

These Brothers would suffer much at the hands of the Roman Emperor. At the time of the Muslim conquest of the Holy Land, the Crusaders freed them. And soon many pilgrims began joining the Order, among them St Cyril, St Angelo and St Simon Stock. Later, when the Brothers began to be persecuted once again, St Cyril, who was then the General, had recourse to Our Lady who spoke thus:

‘It is the desire of My Son and Mine that the Carmelite Order be not only a light for Palestine and Syria but that it may illumine the whole world. Hence, I attracted you to it and shall attract numerous children from all the nations of the world.’

Truly, the Order flourished in various countries. However, in the twelfth century there were many misunderstandings against it in the West.

St Simon Stock

In 1251, Simon Stock, weighed down by age and austerity – he had lived 20 years in the empty trunk of a tree, as penance – went to Cambridge to inaugurate a new Carmelite convent. Meanwhile, his soul suffered a lot in view of the opposition that his Order suffered in his country.

In 1251, Simon Stock, weighed down by age and austerity – he had lived 20 years in the empty trunk of a tree, as penance – went to Cambridge to inaugurate a new Carmelite convent. Meanwhile, his soul suffered a lot in view of the opposition that his Order suffered in his country.

On the night of 16 July 1251, at the height of his suffering, St Simon was praying hard; his fervent prayer was transformed into a marvellous hymn:

Flower of Carmel,

Tall vine blossom laden;

Splendour of heaven,

Childbearing yet maiden.

None equals thee.

Mother so tender,

Who no man didst know,

On Carmel's children

Thy favours bestow.

Star of the Sea.

Strong stem of Jesse,

Who bore one bright flower,

Be ever near us

And guard us each hour,

who serve thee here.

Purest of lilies,

That flowers among thorns,

Bring help to the true heart

That in weakness turns

and trusts in thee.

Strongest of armour,

We trust in thy might:

Under thy mantle,

Hard press'd in the fight,

we call to thee.

Our way uncertain,

Surrounded by foes,

Unfailing counsel

You give to those

who turn to thee.

O gentle Mother

Who in Carmel reigns,

Share with your servants

That gladness you gained

and now enjoy.

Hail, Gate of Heaven,

With glory now crowned,

Bring us to safety

Where thy Son is found,

true joy to see.

Amen. (Alleluia)

The Saint prayed and sang all night. At the first sign of dawn, Our Lady appeared to him, surrounded by the angels, dressed in the habit of the Carmel. She smiled and brought in her virginal hands the Scapular of the Order, with which she clothed the man of God, saying: ‘This is a privilege for you and all the Carmelites. Whoever dies wearing this scapular shall not fall into hell.’

Of course, we cannot be carried away by the false idea that the mere wearing of the scapular is sufficient to win us Heaven. It allows us to hope; we must live a Christian life, fulfilling the Commandments!

Saturday Privilege

In 1316, the Virgin appeared to Cardinal Tiago who, on the second day of the vision, was elected Pope bearing the name John XXII. She spoke to him of a Sabbatine or ‘privilege John XXII’, which was approved and confirmed by Pope Clement VII ("Ex clementi", 12/8/1530), Pope St Pius V ("Superna dispositione", 18/2/1566), Pope Gregory XIII ("Ut laudes", 18/9/1577), and others, and also by the Holy Roman General Inquisition under Pope Paul V (20/1/1613).

In 1316, the Virgin appeared to Cardinal Tiago who, on the second day of the vision, was elected Pope bearing the name John XXII. She spoke to him of a Sabbatine or ‘privilege John XXII’, which was approved and confirmed by Pope Clement VII ("Ex clementi", 12/8/1530), Pope St Pius V ("Superna dispositione", 18/2/1566), Pope Gregory XIII ("Ut laudes", 18/9/1577), and others, and also by the Holy Roman General Inquisition under Pope Paul V (20/1/1613).

Accordingly, ‘it is permitted to the Carmelite Fathers to preach that the Christian people may piously believe in the help which the souls of brothers and members, who have departed this life in charity, have worn in life the scapular, have ever observed chastity [according to one’s state], have recited the Little Hours [of the Blessed Virgin], or, if they cannot read, have observed the fast days of the Church, and have abstained from flesh meat on Wednesdays and Saturdays (except when Christmas falls on such days), may derive after death — especially on Saturdays, the day consecrated by the Church to the Blessed Virgin — through the unceasing intercession of Mary, her pious petitions, her merits, and her special protection.’ (Cf. summary approved by the Congregation of Indulgences on 4 July 1908).

(Talk delivered at Regina Angelorum Cultural Centre, Panjim)

Tomorrow: Significance of the devotion for our day and age

The Fragrance of Carmel (1)

Carmel is a mount that figures in the Old Testament. Devotion to Our Lady began there, indirectly, with Prophet Elijah (also called Elias); it culminated in the formation of the Religious Order of the Carmelites in the thirteenth century. It is a fragrance we are still enjoying!

In 1 Kings 19: 16B, 19-21, we meet Elijah, a prophet who lived in Israel nine centuries before Christ. He proclaimed Yahweh, the one true God of the Israelites, against Baal, a false god of the Canaanites. God worked miracles through Elijah as a sign that he was His favoured one. Because of the sins committed in Israel, the Prophet appeared before the evil king Acab and announced a terrible chastisement. There followed a drought throughout the kingdom.

First resurrection

Elijah withdrew to Sarepta and was helped by a poor and honest widow. She had only flour and oil for herself and her son to consume, after which they expected to die. But she counted the Prophet in and the reward was that flour and oil multiplied in the containers. This is a lesson in heroic faith and confidence that we must have in God.

But then, the son died and, all agonised, the woman said to the Prophet: ‘What did I do, oh man of God? Did you come to my house to remind me of my sins and kill my son?’ Elijah called out to God and the Lord heard his prayer: ‘the little boy’s soul returned to him and he won back his life.’ This was the first miracle of resurrection we see in the Old Testament.

Combative spirit

Combative spirit

After three years in which the kingdom was without dew or rain, Elijah was before the king again. The king asked him: ‘Are you the troublemaker in Israel?’ In a typical example of holy daring or courage, Elijah answered: ‘It is not me who disturbed Israel but you and the house of your father, by abandoning the Lord’s commandments and following Baal.’ Then, turning to the people, he said: ‘When are you going to stop making the mistake of turning to the Lord and to the idol of Baal all at once?’ If the Lord is God, follow him; if Baal is it, follow him.’

Elijah challenged the prophets of Baal to work a miracle. They failed. The people were dumbstruck. Elijah then worked a prodigious miracle on Mount Carmel, bringing fire from heaven for the holocaust, and wood and stones to erect the altar. And the 450 false prophets of Baal, the main responsible for the people’s sins, ‘and Elijah brought them down to the brook Kishon and killed them there.’ (3 Kings: 18: 40) – an example of combativeness for God, a trait lacking in modern man.

Prefiguring the Immaculate Conception

After this healthy and admirable eradication, Elijah began to pray on the Mount. After he implored God to stop the terrible drought, a little cloud began rising from the sea, which soon caused a great shower to fall (3 Kings: 18: 44). This little cloud is interpreted as the symbol of Our Lady and Her Immaculate Conception – because, just as the light and winged cloud rose from the salty sea, without a trace of its bitterness, the Virgin Mary emerged faultless and immaculate from the sea of fallen humanity. Elijah understood this symbolism and was the first to venerate Our Lady.

Elijah’s was snatched from this earth by a chariot of fire. Before that he threw his mantle upon Elisha, who then lived on Mount Carmel. Centuries later, Elijah appeared at the Transfiguration of Our Lord on Mount Tabor and it is believed that he (together with Enoch) will return at the end of the world, to combat the Anti-Christ.

(Talk at Regina Angelorum Cultural Centre, Panjim)

(To be continued: St Simon Stock and the Carmelites – Significance for our day and age)

Fresh Legal Insight

Legal System in Goa, Vol. 1, Judicial Institutions (1510-1982), by Carmo Souza, [Self-published, 1995] pp. 189; Rs 150

Carmo Souza's book on the legal system in Goa is a welcome addition to the literature on a subject hitherto found only in Portuguese. Originally his doctoral thesis submitted to the University of Poona, it traces the developmental history of the judicial system in Goa from 1510 to 1982. This had been singled out for praise by the then chief justice of India, Mr Y. B. Chandrachud, when he inaugurated the Goa bench of the Bombay High Court at Panjim, in 1982.

Logically, the present work should have been preceded by a study on the legislation and legislative institutions of the corresponding period, in an independent volume. This is now expected to be out shortly.

The present volume assumes importance for several reasons. The Portuguese were the first colonial power to set foot and control a vast Oriental empire. Once Goa became their headquarters, the Tribunal da Relação, or High Court, was established in the old city of Goa in 1544. It administered justice at the appeal level to all the Portuguese settlements from the Cape of Good Hope to the China seas. With them was formed the modern concept of international law in trade, commerce, and navigation.

In the introductory chapter, the author refers to old and modern judicial institutions in Portugal and compares them with those set up in the Estado da Índia. Chapter 2 gives a brief idea of the pre-Portuguese judicial system in Goa, including the Comunidades, and goes on to discuss twenty major offices and institutions that administered justice sectionally, that is, "taking into consideration the different interests and pressures rising in the cosmopolitan society created by a maritime empire.” That list includes, among others, the Tribunal da Relação (treated in detail in chapter 3) and the Holy Tribunal of the Inquisition which, says the author, quoting a contemporary (ex-) Jesuit historian, had “apparently won the confidence of the natives.”

Chapter 4 dwells on the tumultuous period from 1800 to 1961, which saw the advent of constitutionalism in Portugal. A new process began with the decrees of 1832/36. Goan territory expanded with the addition of the New Conquests, where the indigenous system of judicial administration was allowed to continue, and uniform dispensation of justice came only towards the end of the nineteenth century.

"Post-Liberation Judiciary” makes up the final chapter. It treats the dismantling of a “vibrant system”. Problems encountered in the transition phase are brought out.

('Panorama', The Navhind Times, 1 Oct 1995. For longer version of the review, see 'Long Arm of the Law', in Herald - The Illustrated Review, 15-30 June 1995)