Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 8

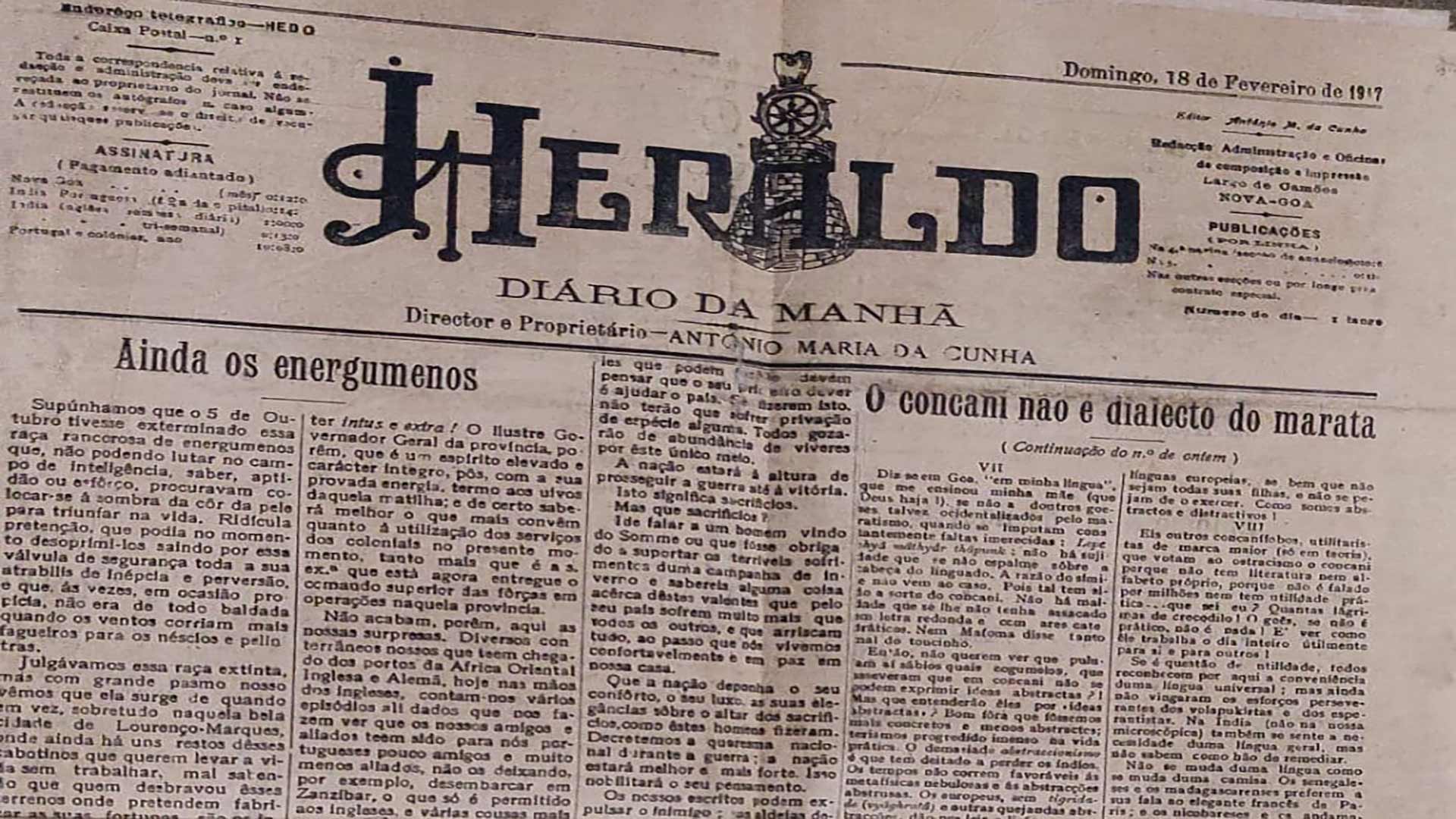

Part 8 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata" – Parte VIII

by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

(In Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2575, 18 February 1917, p. 1)

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

Here are other Konkaniphobes, major utilitarians (only in theory), who ostracise Konkani because it has no literature or alphabet of its own; because it is not spoken by millions nor has any practical use… what do I know? How many crocodile tears! A Goan, if not practical, is nothing! One must see how usefully he works all day for himself and for others!

If it is a question of utility, everyone recognizes over here the convenience of a universal language; but the persevering efforts of the Volapukists and Esperantists are still not vindicated. In India too (not in our microscopic one) the need is felt for a general language, but one knows not how to resolve it.

You can't change your language like the wind. The Senegalese and the Malagasy prefer their speech to the elegant French of Paris; and the Nicobarese and the Andamanese give more value to their speech than to the booming English of London. The Hottentots and the Zulus would not give up their sibilants and monosyllables for the best language in the world.

A self-respecting son does not subrogate his mother, however ugly, poor, ragged, pustulous, for a queen, beautiful as Venus, adorned with byssus and purple, with diamonds from Golconda, pearls from Ceylon and rubies from Pegu. He doesn't ‘kick’ her, as they say there; he doesn't reject her, loathe her; he hugs her, kisses her, helps her, boosts her, lavishes her with all the care and indulgence he is capable of. This is what St John Chrysostom teaches us, speaking of children, who in many ways are our teachers. Or else, the Son of God would not have said: Unless you become like little children, you will not enter the kingdom of Heaven.

I won’t be surprised if over there they know not that in Kanara there is a language, sandwiched between Malayalam (language of the Malabar) and Kannada; it has no literature, no alphabet of its own, is spoken only by five hundred thousand, is stuffed with Sanskrit, Kannada, Malabarian and Hindustani words. It is Tulu or Tulava, which bears more Portuguese terms and closer relations to Konkani than Kannada does. In the opinion of Caldwell and other grammarians, it is nonetheless one of the more developed of the Dravidian family. And till date no one has proposed that it be replaced by one of its more powerful neighbours that lend it their alphabet. On the contrary, Protestant missionaries promote it diligently, by publishing grammars, dictionaries, and other works.

If, however, Goa’s progress and happiness depend on Marathi being the vernacular and vehicle of primary education, may a Hercules arise who will do away with the Konkani hydra; and I will only have to sing his praises, mimicking Pasquin: Quod non fecerunt lusitani, fecerunt canarini.

And then, let's hope that some Nobel prizes will end up in our homeland, as did one, two years ago, in Bengal (to Sir Rabindranath), and that there will emerge an authentic genius, like Chandra Bose, who astonished scientists of Europe and America with those wonderful demonstrations of plant physiology.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, Sep-Oct 2024, pp __

Leap of Faith and Love

Last Sunday, a seventy-year-old shared with me some of her longstanding questions about religion and faith. She is presently beset with physical ailments, and finds it painful to turn them over in her mind. Hers has been quite a long journey, and fearing that it may end abruptly, she asks: ‘What does it take to be saved? Can I simply have faith in Jesus and be saved?’ While this is in itself a worthy act of surrender that will be pleasing to the Lord our God, there are a few nuances to be considered in this regard.

Quite remarkably, today’s Readings point exactly to what it takes to be saved. And this is no coincidence, for He who feeds the birds in the blue sky and the worms in the garden soil, always provides the answers we seek. And as I get down to writing this blogpost, I hear in the background this Merle Haggard song, which I dedicate to all who are on the journey of faith –

I come to the garden alone

While the dew is still on roses

And the voice I hear falling on my ear

The son of God discloses.

And he walks with me and he talks with me

And he tells me I am his own

And the joy we share as we tarry there

None other has ever known.

He speaks and the sound of his voice

Is so sweet, the birds hush their singing

And the melody that he gave to me

Within my heart is ringing.

Let us therefore remember that we are never alone; God is with us and speaks to us at all times, as he did to Isaiah of old. In fact, in the First Reading (Is 50: 5-9), the Prophet says, ‘The Lord has opened my ear, and I was not rebellious. I turned not backward… For the Lord God helps me; therefore, I have not been confounded; therefore, I have set my face like a flint, and I know that I shall not be put to shame; he who vindicates me is near.’

Indeed, whoever trusts in the Lord has nothing to fear. We may be surrounded by the snares of death and anticipate the anguish of the tomb; we may be in the throes of sorrow and distress, yet when we call on the Lord’s name, He will deliver us. He is gracious, compassionate; He protects the simple hearts and saves the helpless. The psalm antiphon therefore invites us to sing with confidence: ‘I will walk in the presence of the Lord in the land of the living.’ We are called to be ever conscious of and grateful for the Lord's presence in the humdrum of our lives; He knows and cares for our every need. No wonder the Psalmist is all praise for the Lord’s mercies.

Even so, often we are ungrateful, as the Jews were, to Jesus. He who had come down from Heaven and wrought signs or miracles, as expected, was rejected by His own. ‘Who do men say that I am?’ He asked. What is our answer to that question that Jesus asks in the Gospel today (Mk 8: 27-35)? Have we have built up a personal relationship with Jesus, as He journeys with us, quietly bearing all our burdens? Only Peter answered correctly – ‘You are the Christ’ – yet when the Master spoke of suffering and rejection and death on the Cross and of rising from the dead, Peter rebuked Him. And Jesus was quick to dub him ‘Satan’, whom he ordered to get behind Him.

This was the first time Jesus was presenting Himself as the Suffering Messiah. There was ample evidence that He was indeed the Son of God, whose horizon was none other than the heavenly kingdom. But the people did not quite understand; they wanted Jesus to care about their earthly kingdom and do away with the Roman subjugation of their nation. As a result, Jesus both disappointed the Jews and angered the Romans. He taught the disciples that the Son of Man would have to suffer many things – and so would those who wished to follow Him.

‘Whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake and the Gospel’s will save it’ can easily be put down as one of the greatest of the Kingdom paradoxes. Here is how worldly logic does not align with God’s wisdom; here is also how our faith does not align with reason. Not that they are intrinsically antithetical. Faith and reason are compatible, and so are science and religion, because truth is but one. Sadly, it is our egos that upset the apple cart; while in faith, we put our hope and trust in God, in reason we seem to trust more in our own powers, and only belatedly realise our folly.

Is Faith alone, then, our salvation? St James in the Second Reading (2: 14-18) states: ‘Faith by itself, if it has not works, is dead.’ Indeed, the Church rejects the ‘faith alone’ proposition, meaning that intellectual faith cannot save us. One needs to cooperate with God’s grace. Rather, our hearts have to move too. And this stirring will ensure that all that we do is out of love: corporal works of mercy[1] and the spiritual works of mercy[2]. That is to say, our faith must be wrapped up in love (charity or supernatural love of God). That is the right leap to take, and the time is now!

[1] Feeding the hungry; giving water to the thirsty; clothing the naked; sheltering the homeless; visiting the sick; visiting the imprisoned, or ransoming the captive; burying the dead.

[2] Instructing the ignorant; counselling the doubtful; admonishing the sinners; bearing patiently those who wrong us; forgiving offences; comforting the afflicted; praying for the living and the dead.

Goencheo Mhonn'neo - IX | Adágios Goeses - IX

Segue uma nona lista de adágios,[1] extraídos do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (1872-1935)[2].

- Concani | 2. Tradução literal | 3. Tradução livre

1. Xelyá angar bibó. | Xellia angar bibo.

2. Sobre o corpo são,

suco de anacardo

(p’ra causticação).

3. Ter injusto sofrimento

ou pena, sem fundamento.

1. Venttó laslyar, vôll vhossó na. | Vennto laslear voll vochona.

2. Uma corda torcida

estando até queimada,

a sua torcedura

não fica desvincada.

3. Apesar de estar punido,

não fica ele corrigido.

1. Duddú nant taném tarir poiló bossunk zay. | Duddu nant tannem tarir poilo bosunk zai.

2. Numa barca de passagem,

deve meter-se primeiro

quando alguém, para pagar

o nauta, não tem dinheiro.

3. Quem não tiver protecção

deve ir sempre, antes de outros,

fazer sua petição.

[1] Cf. oitava lista, Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 29, julho-agosto de 2024, p. 51.

[2] Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda, Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), com acrescentamento dos adágios na grafia moderna, pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, Sep-Oct 2024, pp __

Ephphatha… be opened!

Last Sunday, we saw how God expects us to give ourselves over to Him; today we see Him as a merciful Healer who gives Himself over to us. Truly liberating is this attitude of trust and give-and-take. It liberates us socially, psychologically, spiritually. It is refreshing, vivifying, life-giving. It makes us free in Christ.

Freedom and happiness are among the soul’s deepest yearnings. They were ours for free until the fall of our first parents. Then, God made several covenants with man, but they too failed to yield enduring results. Prophet after prophet cried out in the wilderness. So it was with Isaiah; in his ‘little apocalypse’ he dwells on God’s final judgement upon nations hostile to Israel (chapter 34) before he talks of the country’s final salvation (chapter 35).

Today’s First Reading (Is 35: 4–7) is filled with the blessing of salvation. It addresses our fearful hearts. ‘Be strong, fear not!’ says the Lord. So, fortitude is what we must summon up in the face of ostracism, persecution, infirmity, discouragement and disappointment. God promises to cure the blind, the deaf, the mute, the lame. He who is the undisputed Creator of the universe will also let waters break forth and cool the sands of the burning desert.

The good news is that God’s richly metaphorical language translates into very concrete things. We are those weaklings that need His support; the earth is that victim of human recklessness, and which He alone can restore to pristine glory. Miserable as we are every step of the way, we long for His fatherly care and support. He comes to our aid and vindicates us. The Psalmist (145: 6c-7, 8-9a, 9b-10) has it on record that ‘it is the Lord who keeps faith forever.’ And, of course, if God is for us, who can be against us? (Rom 8: 31)

That is what we see in today’s Gospel (Mk 7: 31-37). Our Lord travels through Tyre and Sidon, rich cities (and regions) on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, in modern-day Lebanon. He took that circuitous route to the Decapolis, a group of ten Greek city-states now located in Jordan, Israel and Syria. He left Galilee because of the fierce dislike that the Pharisees had for Him. He took advantage of his self-imposed exile to instruct His disciples and to announce the Good News to the Gentiles.

In some city of the Decapolis, Jesus was presented with a deaf-mute. They wanted Him to lay His hands on him. Taking him aside from the multitude, Jesus put His fingers into his ears; and with His saliva, He touched the man’s tongue. Then, looking up to heaven, Jesus sighed and said to him: ‘Ephphatha’, that is, ‘Be opened.’ Never mind if that sounds too emphatic to our ears, Our Lord’s gentleness sufficed. It may be noted that He looked up to His Father and very typically ‘charged them to tell no one’ what miracle they had witnessed.

Only St Mark recounts this episode. Scripture scholars say that, instead of merely signaling or uttering a word, Jesus made it a point to touch the ailing organs, as a sacramental sign. And why did He charge them not to tell anyone? This is that ‘Messianic secret’, stated by Matthew and Luke, too, but almost institutionalized by Mark! This Evangelist reports that Jesus forbade the devil from revealing his identity; those healed, from reporting the cure; and the disciples, from revealing to strangers what they had learnt from their Master.

Let us understand that those instructions were designed to rule out wrong notions about Jesus’ ministry. He did not wish to be seen as a political liberator but as a liberator of consciences. He moved the hearts and minds of people and touched the deepest recesses of their souls. He provided them with means to achieve spiritual serenity, not political peace. The cures he wrought were messianic signs, given in response to what the Jews had always expected from a long-awaited Messiah…. But ironically, they saw the signs but did not recognize the Messiah!

The Second Reading (Jam 2: 1-5) is taken from James. He is not to be mistaken for James the Great, brother of John the Evangelist and first apostle to be martyred; nor for the other, lesser apostle of the same name, son of Alpheus. The epistler James, a relative of Jesus and usually called ‘brother of the Lord’, was close to the Apostles but began to believe in Jesus’ divinity only after the Resurrection. He was chief of the Jewish Christian community of Jerusalem.

Finally, the Letter once written to ‘the twelve tribes of the Diaspora’ – more specifically, to the Judeo-Christian members of those diasporic tribes – enjoined them to treat the rich and the poor, the healthy and the sick, the educated and the uneducated with the same graciousness: all had to experience the love of God. The said Letter is now addressed to you and me, with an emphatic message – Ephphatha – a clarion call to open our minds and hearts to the Lord our God and, filled with gratitude for the many blessings and graces received, announce His Good News from the rooftops!

In letter and spirit

At the end of a week when Our Lord repeatedly rebuked the Scribes and Pharisees – ‘Woe to you, hypocrites’; ‘Woe to you, blind guides’, and so on – and then put before his disciples the delightful imagery of the Bridegroom who arrives at an hour we least expect, and the Master who, on seeing that a servant has squandered the talent, casts him into the outer darkness where men will weep and gnash their teeth; this Sunday we are warmly encouraged to conform to God’s law, which always turns to our moral and spiritual advantage.

But how will such a call be picked up by the contemporary world in which pride and individualism reign, where every one considers themselves to be the law, or above it? Of course, such thoughts seem to arise mostly where God’s law is concerned; human laws – even if illicit or immoral – are followed blindly. We fail to see that, while humans make laws to suit individuals, lobbies, or regimes, God’s laws are above board and apply to both prince and pauper. Yet, we find fault with these – for God is up there, silent, as though inexistent, whereas humans down here are vociferous and exacting...

The First Reading (Deut. 4: 1-2, 6-8) rails against such inversion of principles and values. It highlights the importance of lovingly obeying God’s commandments; keeping them does not make us blind but wise and understanding. None should tinker with the law, reinterpret it, and much less dare to twist it. The Lord is very clear: ‘You shall not add to the word which I command you.’ Integrity should be our watchword. We must seek to follow God’s law in letter and spirit, with sincerity of mind and heart.

The Gospel (Mk 7: 1-8, 14-15, 21-23) clinches it. The Pharisees and the Scribes object to the disciples eating with hands unwashed, foolishly believing they would catch Jesus on the wrong foot. But Our Lord comes down heavily on them, quoting Isaiah, whom the scholars ought to have known: ‘These people honour me with their lips, but their heart is far from me; in vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the precepts of men’. Jesus further charged them, saying: ‘You leave the commandment of God, and hold fast the tradition of men.’

Obviously, Jesus had nothing against tradition as long it was in keeping with God’s law – and it did not become the law! In fact, only God and religion can be higher than tradition, which has the unique ability of putting the spotlight on the truth, goodness and beauty of God’s law. Or, as the Second Reading (1 Jam 1: 17-18, 21-22, 27) points out: ‘Every good endowment and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights with whom there is no variation of shadow due to change’ (emphasis ours).

What exalted words that expose the inanities we so often hear: that the Church must ‘move with the times!’ But how? By accepting the false standards of the world, by falling in love with its ways, by falling prostrate to it? Isn’t all of this happening in the name of adaptation, and isn’t that how Christian civilization is being put through a process of paganization? What a far cry from what Pope Leo XIII teaches in Immortale Dei, that wonderful Encyclical on the Christian constitution of States:

‘There was once a time when States were governed by the philosophy of the Gospel. Then it was that the power and divine virtue of Christian wisdom had diffused itself throughout the laws, institutions, and morals of the people, permeating all ranks and relations of civil society. Then, too, the religion instituted by Jesus Christ, established firmly in befitting dignity, flourished everywhere, by the favour of princes and the legitimate protection of magistrates; and Church and State were happily united in concord and friendly interchange of good offices.’[1]

A word to the wise is enough. You can apply the papal concern to the abysmal state of affairs in the countries and continents you live in. In the name of Enlightenment celebrating reason and downplaying faith, the world began rejecting many traditional religious and political ideas that held society together. Under the pretext of secularization, which started with the French Revolution, all -isations flourished, except Christianisation. In the guise of an equal society, some became ‘more equal than others’, and in the name of emancipation, in the May ‘68 civil unrest in France, for example, it was forbidden to forbid!

The world can easily turn topsy-turvy when God is left out of the picture. It is not without reason that St James calls God the ‘Father of lights’ – He is indeed the true Enlightenment! And when Moses called upon his people to be a ‘great nation’ – a model in the sight of the peoples – he was probably referring to Greece, holder of a great artistic and philosophic culture, and to Rome, which enjoyed wide political power. But neither country could hold a candle to Israel, who had ‘a god so near to it as the Lord our God is to us, whenever we call upon Him.’

We are the new chosen people of God. We must ‘receive with meekness the implanted word, which is able to save your souls.’ But we must also ‘be doers of the word, and not hearers only,’ earnestly observing His law in letter and spirit.

[1] https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_01111885_immortale-dei.html

Lord of All History

The First Reading taken from the Book of Joshua and St John’s Gospel text today are well aligned. They impress upon us the supreme concern to worship the One and Only God of History. The Jews were called to do this then; we are to do it now and always.

Joshua was the leader of the Israelite tribes after the death of Moses. He conquered Canaan and distributed its lands to the twelve tribes. His story is told in the Book of Joshua –the sixth book of the Old Testament – which is the story of Israel from the conquest of Canaan to the Babylonian exile.

Realising that he was ‘going the way of all the earth’ (23: 14), Joshua addressed the tribes a second time, at Shechem. He recalled how God had formed their nation and appealed to his people to shun all the false gods that their ancestors had worshipped. The people solemnly promised to worship ‘the Lord our God who brought us and our fathers up from the land of Egypt, out of bondage, and who did those great signs in our sight.’

This is a lesson for all times. Your ancestors and mine who became Christian did so by the grace of God. As Jesus says in the Gospel today (Jn 6: 60-69), ‘No one can come to me unless it is granted him by the Father.’ Our ancestors responded to the call and we, like the Israelites of old, remain eternally grateful. We are also called to remain faithful, to not vacillate but trust in the Lord always. No pagan festival should ever tempt us to break the First Commandment. The Lord our God and Creator of the Universe is the Lord of History. ‘He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together’ (Col 1:15-17).

Coincidentally, while the First Reading is taken from the concluding chapters of the Book of Joshua, the Gospel text is the conclusion of the Bread of Life discourse. Joshua was at the end of his life, and Jesus, ending the second year of His ministry. At this point, many disciples had found the Master’s doctrine a bitter pill to swallow: ‘This is a hard saying; who can listen to it?’ Not paying heed meant not believing that He was the Son of God. No wonder Jesus said, ‘Then what if you were to see the Son of Man ascending where He was before?’

Jesus knew that they hankered after ‘signs.’ And what about us? We tend to think there are fewer miracles today than in the past (when, for sure, there are more miracles than we even get to know of). Anyway, how many ‘signs’ do we need to believe in Him who often cured – and still cures – the humanly incurable; raised to life the dead, and Himself rose on the third day…? Let us not pamper our senses, or test God, by looking for miracles. Let us remember that nothing can surpass the Lord’s Resurrection, which is the bedrock of our faith.

In fact, we must be unreservedly proud of Our Lord who is the Way, the Truth and the Life. His Body and Blood are a guarantee of life eternal. With Him we have everything; without Him, nothing. Hence, when asked if the rest of the disciples too would go the way of other apathetic ones, Peter replied: ‘Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life; and we have believed, and have come to know, that you are the Holy One of God.’ Indeed, ‘it is the spirit that gives life, the flesh is of no avail’; and the words that the Lord our God speaks to us are spirit and life.

Knowing that He would be returning to the Heavenly Father, Our Lord instituted the Holy Eucharist and the Priesthood, besides giving us the commandment of love. He also left us the Church, which is now and forever His visible Body, the visible sign of God’s kingdom on earth. And to Peter, the disciple with the winning answer, he said, ‘You are Peter, and on this rock, I will build my Church” (Mt 16:18). He also called his Church a sheepfold, stating that ‘there shall be one flock, one shepherd’ (Jn 10:16).

However, more pertinent this Sunday is the metaphor of the bride, for St Paul in the Second Reading applies the imagery and symbolism of marriage to Christ and the Church. While the Apostle exhorts wives to be subject to their husbands – ‘for the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the Church, His Body, and is Himself its Saviour’ – he more importantly commands us believers, who are the Church, to be subject to Our Lord the Bridegroom.

The secular world may not care much for what is to come, just as much as the ‘wisdom of the world is foolishness in the sight of God’ (1 Cor 3: 19). It behoves us, then, to never stop loving Christ and the Church. We must enjoy a holy pride in the now bicentennial and eternal institution. Whereas the world grudgingly recognises her role in the formation of civilisations, and even attempts to pull the rug from under her feet, we Christians must cling to the central figure in all of history. For, as Pope Benedict XVI once put it, ‘the fate of history, our fate, depends on one individual: Jesus of Nazareth.’ He is indeed the Lord of all History.

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 7

Part 7 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata – VII", by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

Published in Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2575, 18 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha and published in

Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 29, July-August 2024, pp 29-31

Lepechyâ mâthyâr thâpunk: there is no dirt that does not spread over the flounder’s head. This is said in Goa, ‘in my language’, which my mother (may she rest in peace!) has taught me, even it is not that of other Goans perhaps westernised by Marathism; when unwarranted faults are constantly imputed. The reason for the simile is beside the point. For such has been the fate of Konkani. No evil has been left unattributed to it in print and with a professorial air. Not even Mohamed has so viciously bad-mouthed bacon.

Do you not see, then, that the place is swarming mushroom-like with learned men, who state that in Konkani one cannot express abstract ideas? But what do they mean by ‘abstract ideas’? If only we could use more of concrete rather than abstract language; we would have made much progress in practical life. Too much of abstractionism is what is destroying the Indians. The present times are not conducive to nebulous metaphysics and abstruse abstractions. The Europeans, without tigritude (vyaghratā) and other such abstractions, provide us with laws and lessons.

But is it true that the spoken language of the Goan Christians has not a word to denote abstract ideas? And the current and past preachings, do they only deal with concrete things about the cult of linga, yoni, xaxti, Betalla, king cobra? And so many manuals and devotionals, besides books and newspapers that are published, especially in Bombay, don't they contain abstract ideas?

And the Christian catechism? Surely, that's not Marathi. A philological authority has already stated that pottárth, alpabhojan, sadaiv, and other such terms do not exist in Marathi and Sanskrit or do not have the connotations that we assign them. Now, the catechism has hundreds of words like those to designate dogmas and mysteries, virtues and vices, gifts and fruits of the Holy Spirit, dispositions for the sacraments, etc. Are they all concrete words?

Hence, I would have liked to be in Goa and at a public contest see who has abstract ideas, whether a Christian lad with just the knowledge of the Konkani catechism, or a Hindu lad, of the same age, with wide knowledge of Marathi. I do not for a moment hesitate to say that the Christian would carry off the palm.

The reason is obvious to those who know what generally professed Hinduism is. It is in essence more elastic than rubber. That is why it does not have a catechism, a code of doctrines and precepts. Ask a cultured Hindu to state in a few words what he should believe and practice in accordance with his religion, and see the result. It would not be the same with a Buddhist or a Jain. An orthodox Hindu is he who accepts the Vedas in theory, even if he has not seen them, and caste distinctions in practice, even if he cannot explain himself. The rest hardly matters. Philosophers and theosophists have mercilessly rattled the Vedas with their doctrines, but did not openly repudiate them. And that was enough.

If, to express abstract ideas, the Marathists constantly turn to Sanskrit vocabulary, does not Konkani have the same right? Or is Sanskrit the monopoly of the Bhonsles, and no other can touch it? European languages have equal right at least to Greek and Latin, even though they are not all their children; and they do not hesitate to exercise it. How abstract and distracting we can get!

Bread of Wisdom

This Sunday, the Readings and the Psalm focus on wisdom. We get to see how worldly wisdom is no wisdom at all, and how divine wisdom has provided food for thought since times immemorial.

In the First Reading (Prov. 9: 1-6), wisdom is personified by a woman who has built her house on seven pillars. She gears up for the inauguration by slaughtering her animals and mixing her wine. (‘Mixing’, because with the process of distillation still unknown, the potency of wine was increased by the addition of herbs and spices). After she has set her table, she sends out her maids to call the meek and humble of heart to partake of her bread and wine. Whereas she has invited ‘whoever is simple’, she exhorts whoever is ‘without sense’ to walk in the way of wisdom. That is to say, one is expected to be simple, but never naïve.

The Psalm (33: 2-3, 20: 11-15) reminds us that the wise bless the Lord at all times, give him glory and praise. The humble are always happy to hear about God; they revere Him and the saints and feel blessed. The Lord calls us his ‘children’ and also counsels us to live devoutly, guarding our tongue and lips from falsehood. He lets us in on this secret of a long and happy life, which, alas, only the wise understand. We are told that it is not enough to shun evil but also proactively seek to do good. And, even while we engage in war to defend truth and justice, we must continually strive after peace: a lesson that only the truly wise imbibe.

In the Second Reading (Eph 5: 15-20), St Paul too exhorts us to tread life’s path wisely. This involves keeping good company and never wasting one’s time. Of course, understanding the will of God is the touchstone. The Apostle to the Gentiles views wine and song with scepticism, for both tend to slacken the will and cause reason to falter. He therefore recommends that talking and feasting be focussed on the Lord. Finally, the aim is to extol Him and at all times to give Him thanks.

To achieve the goal of a proper moral formation, the Angelic Doctor St Thomas of Aquinas points to the theological virtues – faith, hope, and charity. While they all happen through union with God, it is through charity, or love, that our will and faculties are aligned to the supernatural end. Our life’s efforts are a waste of time if we do not cultivate the virtues; in fact, everything is futile unless centred on God. And once God becomes the alpha and omega, the cardinal virtues of temperance, fortitude, prudence and justice come into play. Temperance and fortitude moderate the passions; prudence enlightens reason, and justice regulates the will.

That may seem like a roadmap to virtuous Christian living, yet it is not enough. ‘A virtue is a habitual and firm disposition to do the good’ (CCC 1803) but it is carried forward not by itself but by the gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord (cf. CCC 1830-1831). And sustaining it all is the Holy Eucharist, rightly called ‘the source and summit of the Christian life’ (CCC, 1324). Herein we encounter the bread which Jesus has given ‘for the life of the world’ and so, ought to occupy a central place in our day-to-day life.

From the Gospel text (Jn 6: 51-58), the fourth instalment of the Bread of Life discourse, we know how many Jews abhorred Our Lord’s teaching on his Body and Blood. On the other hand, much that is said about the Eucharist may now seem obvious to us, for we have been taught that the Sacrament is Our Lord’s redemptive Sacrifice at Calvary; that the Bread is Our Lord’s Body and the Wine is His Blood; that Jesus’s presence therein is real, and that partaking of it is a sure means of growing closer to Him. But then, have we had the opportunity to systematically reflect and internalise the doctrine? This is of the essence.

In conclusion, while a little beyond today’s text from the Book of Proverbs, a contrast is established between a wise lady and a foolish woman; and the Second Reading juxtaposes the sagacity of Christian life with the stupidity of godless living, the Gospel effectively draws our attention to the wisdom of Our Lord’s words – ‘I am the living bread that came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever’ – vis-à-vis the world’s reckless materialism. The saving grace is that wisdom has come to us in the Incarnation of the eternal Word of God, Jesus Christ Our Lord.

Banner: https://rb.gy/py45eb

Goencheo Mhonn’neo - VIII | Adágios Goeses - VIII

Segue uma oitava lista de adágios,[1] extraídos do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (1872-1935)[2].

Concani | Tradução literal | Tradução livre

Unn dudatçó gôntt guilunk nuzó, ani bayrui galunk nuzó. | Hun dudhacho ghontt gillunk nozo, ani bhairui ghalunk nozo.

Um gole de leite quente,

(tomado sem reflectir,)

não se sabe se o deve

deitar fora ou engolir.

Há muitas vezes embaraços

que metem em tal situação,

que não se sabe, no momento,

como sair da entalação.

Variante

Quando alguém é dependente

de dois rivais, em questão,

fica indeciso p’ra dar

Sua franca opinião.

Kaddi báil ghovachi, gori báil povachi.[3] | Kalli bail ghovachi, gori bail povachi.

A mulher preta é

do esposo somente.

mas a mulher clara

é de toda a gente.

A mulher feia é só do homem,

com quem está desposada,

mas sendo a mulher bonita,

é por todos requestada.

-o-o-o-o-

[1] Cf. sétima lista, Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 27, março-abril de 2024, p. 47.

[2] Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda, Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), com acrescentamento dos adágios na grafia moderna, pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

[3] ‘Povachi’ = do povo.

(In Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 29, Julho-Agosto 2024, p. 51)

Bread and Faith

Today’s Readings are yet another affirmation of our ancestors’ faith and trust in the Lord’s never-failing love and care. He is indeed a Provider par excellence; He sustains us, and never lets us down. May generations believe that He is our everything, and nothing shall we want!

In the First Reading (1 Kings 19: 4-8), the Prophet Elijah, threatened by king Ahab and queen Jezebel, feels forsaken and desperate. He goes into exile and, when exhausted from walking no end, sits under a broom tree, crying, ‘It is enough; now, O Lord, take away my life.’ He would have readily died in the desert where his ancestors had wandered for forty years; but God had a different plan. The angel of the Lord urged him to rise, feed himself and get going. The prophet then went to mount Horeb (also called Sinai), where he spent forty days and forty nights.

They say, man proposes; God disposes. Elijah’s cry ‘Satis est, Domine, satis est,’ was also the cry of so many holy men after him, including our own St Francis Xavier. But then, God turned the situation to Elijah’s advantage. The prophet felt spiritually renewed on God’s mount. That was the soil that his ancestors had stepped on and were given the Torah, of which Elijah was presently the depositary and interpreter. It was the site where God had appeared to Moses; and Elijah was now defending the principles of the Mosaic Covenant, against the prophets of Baal, who were on the royal payroll.

In the Gospel (Jn 6: 41-51) we have the New Testament counterpart of several episodes of the Old Testament. The Bread of Life discourse that began on the seventeenth Sunday of this year is now in its third instalment. Today, we hear Jesus say, ‘I am the Bread which came down from heaven.’ The message that the angel gave Elijah a millennium earlier is now perfected. Truly, ‘the grass withers, the flower fades, but the word of our God will stand forever’ (Is 40: 8).

Picking up from we left off last Sunday, we know from today’s Gospel text that the Jews murmured at Jesus, because of His unprecedented claims. They checked His credentials – ‘Is not this Jesus, the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know…’? – but somehow, they failed to discern His divine origin. Jesus, the Son of God, did not stop to placate the people but went ahead and reiterated His message, saying: ‘No one can come to Me unless the Father who sent Me draws him; and I will raise him up on the last day.’

Jesus wanted to let the people know that they needed a special grace to come to Him. It was not a privilege that they could bestow upon themselves; rather, God had to favour them with the required grace. It did not come easy. Hence, Jesus did not labour the point but rather restated it very categorically: ‘I am the Living Bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever.’

The Living Bread is not our everyday physical bread, which anyway cannot sustain us; it is spiritual bread that is life-giving… Next Sunday, Jesus will go a step further and explain that, really speaking, the bread He gives for the life of the world is His flesh. This is not a message for the faint-hearted but for those who have total faith and trust in the True God. It preannounces the institution of the Holy Eucharist – that ineffable Sacrament in which Our Lord gives Himself to us as the heavenly Food and Drink.

We Catholics must consider ourselves extremely privileged and thankfully share in such an exalted Mystery. We who have been thus ‘sealed for the day of redemption’ ought not to disappoint the Holy Spirit of God. In fact, in preparation for that day, St Paul in the Second Reading (Eph 4: 30; 5: 2) exhorts us to give up all bitterness, wrath, clamour, slander, malice; and to be kind, tender-hearted, forgiving and imitators of God. Finally, he says, we must ‘walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave Himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God.’

Does that smack of weakness? Not at all. And what Jesus said to St Paul, He says to us today: ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness’ (2 Cor 12: 9-11). All that we need to do is to believe in the Real Presence of the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist. Lo and behold, He who ‘died’ two millennia ago is still the Living Bread. He is alive!... And our faith, how alive is it?

Banner: https://rb.gy/xgxi7l