Mauzó recebe o galardão Jnanpith

July 5, 2023Jnanpith,Goa,Literatura goesa,Konkani,Mauzo,ConcaniReport,Translation

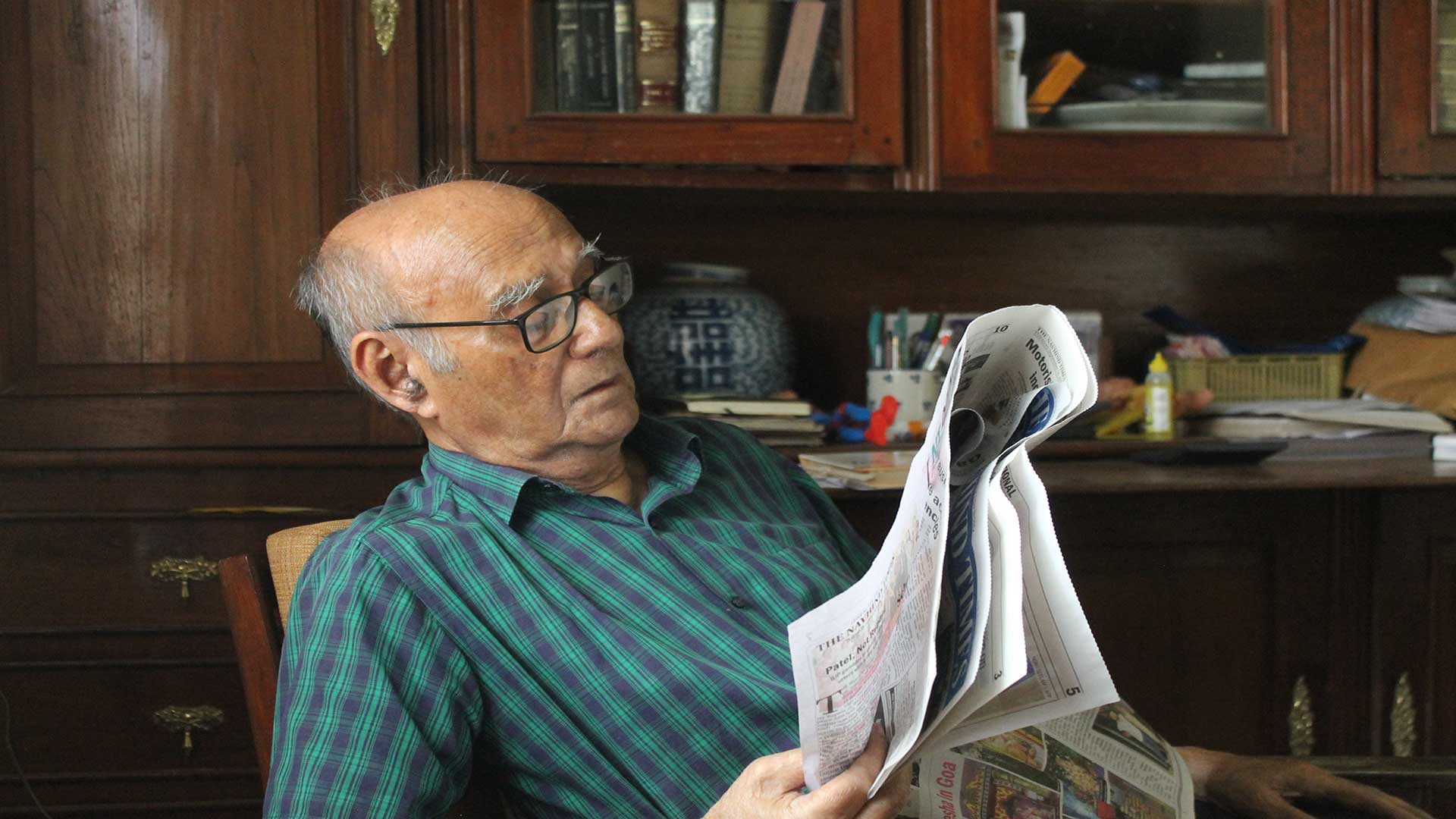

“My language has never let me down," says Writer Damodar Mauzo

"A minha língua nunca me decepcionou," disse o escritor Damodar Mauzó.

Reportagem de Brian de Souza | Traduzido do inglês por Óscar de Noronha*

No seu discurso de aceitação do galardão Jnanpith, Damodar Mauzó discorreu sobre as suas inspirações criativas; sobre o que lhe representa o concani; e a necessidade de criar uma atmosfera que garanta a liberdade de expressão.

“Inspiro-me na minha terra natal, no meu povo e na minha língua”, disse Damodar Mauzó no seu discurso de aceitação do prestigiado prémio literário Jnanpith que lhe foi conferido, relativo ao ano de 2022.

Mauzó recebeu o galardão após a leitura da citação, numa cerimónia muito concorrida, realizada no Raj Bhavan, residência oficial do governador de Goa, P. S. Sreedharan Pillai, em maio de 2023.

“Na expressão das minhas ideias, a minha língua nunca me decepcionou”, reiterou Mauzó, de 78 anos, no seu discurso. Essas palavras captaram a essência da sua longa caminhada com a língua concani, que disse que ama e a qual, “por sua vez, muito me ama”.

Então, por que escreve Mauzó? Disse sucintamente: “Escrevo porque tenho algo diferente a contar e/ou a contar algo diferentemente”.

É apenas o segundo escritor da língua concani a receber este prémio; o primeiro foi o falecido Ravindra Kelekar, quem Mauzó cortesmente reconheceu como seu mestre. Kelekar liderou o movimento literário goês no pós-1961.

A obra literária de Mauzó é vasta e inclui vários géneros. Na sua carreira de 50 anos, publicou 6 colecções de contos, quatro romances, dois esboços biográficos, livros infantis e um grande volume sobre a saga do concani, no qual descreve as dificuldades sofridas à conta dos sequazes da língua durante o regime colonial português.

Mauzó publicou a sua primeira colecção de contos, Ganthan, em 1971, porém, foi só em 1983 que alcançou fama pelo país inteiro, com o romance Karmelin, sem dúvida, a sua obra mais conhecida, com a qual venceu o prémio da Sahitya Akademi. Nesse romance, Mauzó destaca as lutas de uma goesa que, para o seu ganha-pão, se desloca para o Médio Oriente. Escrito no auge da emigração goesa para o Golfo Pérsico, foi bem recebido e traduzido para 14 idiomas. É uma obra seminal sobre a experiência goesa nessa parte do mundo.

Dizendo-se um leitor voraz, Mauzó também prestou homenagem, entre outros, a escritores como Mahasweta Devi, José Saramago e M. T. Vasudevan Nair, os quais disse admirar. Também reconheceu a influência de Saratchandra Chattopadhyay, escritor bengali, que, segundo Mauzó, falou da sua dívida para com os necessitados (“suas lágrimas e desamparo”), que dão tudo, mas não recebem nada, e de Charles Dickens, que citou para “afirmar a sua crença (de Mauzó) no amor e na compaixão”.

A musa criativa de Mauzó foi sempre o homem comum goês, retratado tão eloquentemente no romance Karmelin, enquanto os temas das suas obras incluem o género, a casta, a religião e outros aspectos da condição humana. Como parte desses temas, a sua obra investigou a migração, o turismo e a mineração, que até hoje têm relevância em Goa, pois são questões debatidas no domínio público.

Mauzó referiu-se ao percurso literário do concani que, segundo ele, “sofreu golpes tremendos às mãos da sua história”. Isso também é algo que ele experimentou em primeira mão como membro do comité director do Konkani Porjecho Awaz (Voz do Povo Concani) de Goa, pois sofreu várias pauladas da polícia enquanto se debatia para que o concani viesse a ser conferido o estatuto de idioma oficial.

Enquanto as suas realizações literárias o colocaram sob os olhares da opinião pública, a sua paixão pela liberdade de expressão também veio a conferir-lhe grande projecção quando veio à tona uma ameaça à sua vida, após o assassinato da jornalista-activista Gauri Lankesh. Mauzó era então dirigente do Dakshinayan Abhiyan, um movimento lançado contra a discriminação de castas e ataques à intelectualidade e ao racionalismo.

Nada disso teria diminuído o espírito de Mauzó, pois continua a escrever e aparecer regularmente em festivais literários, incluindo o GALF (Festival de artes e literatura de Goa), do qual ele é co-fundador e co-curador.

Nascido em 1944 na Goa portuguesa, ora Estado da Índia, Mauzó fez os seus primeiros estudos, até o primeiro grau, em português, conjuntamente com os estudos primários em marata, tendo depois ido para Bombaim, onde se formou pelo PA Podar of Commerce. Começou a escrever no final da adolescência e continua a fazê-lo, não conhecendo outra ocupação além da loja que dirigia até recentemente.

Era mesmo de esperar que, ao encerrar o seu discurso, Mauzó, ou Bhaiee, como é carinhosamente apelidado esse lutador apaixonado pela liberdade de expressão, se pronunciasse sobre esse direito humano vital. Servindo-se da analogia das rodovias, que ora estão a ser construídas pelo país, afirmou que também há necessidade de “uma rodovia que suavizará o ritmo acelerado da literatura, eliminando obstáculos mentais dos escritores, fortalecendo as pontes de traduções e criando uma atmosfera encorajadora para a liberdade de expressão”.

* Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisboa, No. 23, Serie II, Julho-Agosto de 2023, pp 45-48 https://rb.gy/8qj52

God above Self

Placing God above ourselves in word and deed is a sign of our openness to His presence and action in our lives. When we receive God’s representatives, we welcome God Himself; when we place ourselves at their service, it is the Almighty that we serve. In fact, we cannot do without Him: a reminder to the contemporary world that has closed in on itself.

The First Reading (2 Kings 4: 8-11, 14-16a) introduces us to Elisha and to an unnamed, wealthy woman who served him and, upon discerning his holy vocation, sheltered him. Elisha, who was himself the son of a wealthy landowner, had left hearth and home on being selected to succeed Elijah in the prophetic mission. He spent time with Elijah on Mount Carmel; later, he served as royal advisor and became known throughout the kingdom as a wonder worker – not least among the wonders being the blessing of a child to his long childless benefactress.

However, the focus is not on accomplishments but on total trust in God and commitment to His message. This is a point that Our Lord highlights in the Gospel (Mt 10: 37-42) when He says that those who love their kith and kin more than they love Him are not worthy of Him; those who love their life are bound to lose it whereas those who lose it for Jesus’ sake will find it. Whoever takes exception to the Lord’s words knows neither the ways of the world nor the ways of Our Lord: The world appears sweet but is deceitful, whereas Jesus, who comes across as harsh, is truthful.

Jesus is no politician currying favour with His people. He is incredibly frank, straightforward, even blunt – but never false. He does not promise us a bed of roses; on the contrary, He invites us to take up our crosses. He does not encourage us to seek service but to serve as He did, unto death. He does not point to a highway but to the narrow path to Heaven. Had we – not individuals alone but countries as a whole – wholeheartedly embraced the philosophy of the Gospel, the world would have been a better place to live in.

Pope Leo XIII in his memorable encyclical Immortale Dei (1885) [1] reminds us of how once upon a time the world had found favour with God: “There was once a time when States were governed by the philosophy of the Gospel. Then it was that the power and divine virtue of Christian wisdom had diffused itself throughout the laws, institutions, and morals of the people, permeating all ranks and relations of civil society. Then, too, the religion instituted by Jesus Christ, established firmly in befitting dignity, flourished everywhere, by the favour of princes and the legitimate protection of magistrates; and Church and State were happily united in concord and friendly interchange of good offices. The State, constituted in this wise, bore fruits important beyond all expectation, whose remembrance is still, and always will be, in renown, witnessed to as they are by countless proofs which can never be blotted out or ever obscured by any craft of any enemies. Christian Europe has subdued barbarous nations, and changed them from a savage to a civilized condition, from superstition to true worship. It victoriously rolled back the tide of Mohammedan conquest; retained the headship of civilization; stood forth in the front rank as the leader and teacher of all, in every branch of national culture; bestowed on the world the gift of true and many-sided liberty; and most wisely founded very numerous institutions for the solace of human suffering. And if we inquire how it was able to bring about so altered a condition of things, the answer is beyond all question, in large measure, through religion, under whose auspices so many great undertakings were set on foot, through whose aid they were brought to completion.”

Contrast the Pope’s prophetic words with our condition today. The world is in a shambles, with atheism, materialism and individualism reigning supreme. No wonder, Russia has spread its errors across the world and is now attacking Ukraine for petty gains; France, formerly considered the eldest daughter of the Catholic Church, has been facing unrest; and in our country, the social and political scene is unbelievable – so enormous that our Shepherds finding themselves speechless have left the sheep to be devoured by the wolves. Against the particularly devastating scenario in Manipur, Archbishop Peter Machado of Bangalore has been the lone voice crying in the wilderness – God bless him! Meanwhile, the encouraging words from the state's new dispensation for the services traditionally rendered by the Christian community have provided human solace to the archbishop. Proof that the Lord keeps His promises and never abandons those who decidedly stand by Him.

Against this dismal background only the Gospel can give us hope, set us free. St Paul in the Second Reading (Rom 6: 3-4, 8-11) invites us to reflect on the fact that with baptism in Christ we die to sin and are on the path to our final glorification. Therefore, putting God above everything is a good idea. We could well say that only devponn (divinity) can protect our munisponn (humanity), only godliness can save our humaneness. That is Jesus’ radical call for discipleship. So, let us shed our natural approach to life and live supernaturally, putting God first in everything we do. Such a worldview may alienate those kith and kin accustomed to overrating the world; but it will surely keep us at peace with God. We ought to allow nothing to come between us and our God and Saviour, to whom we owe our very existence.

Banner: https://givenscreative.com/2022/11/a-week-of-challenge-servanthood-before-self/

Truth and Trust

Isn’t it ironical that everyone believes that truth must prevail but few are ready to hear the truth (especially when it concerns themselves) and act on it? Scientist, politician and layman alike want to change the world ‘for the better’, yet few have the courage to confront the real truth. Maybe we just don’t trust that the truth will keep us afloat – save us – or maybe we are simply too lazy to change our crooked ways. At any rate, we fail to stand by what is good, right and true and succumb to the forces of darkness. Such lack of integrity will sooner rather than later destroy the social fabric and, what is more, sever our ties with God.

In the First Reading (Jer. 20: 10-13), we see Jeremiah entrusted with a very difficult mission: to announce to unfaithful Jerusalem that it was soon to be torn apart. The people responded with a smear campaign; even friends issued threats and awaited the Prophet’s fall. But Jeremiah was unshakeable: “The Lord is with me as a dread warrior; therefore, my persecutors will stumble, they will not overcome me.” He notes how God “tries the righteous” and comes to their rescue. A lesson in perseverance in the face of opposition.

How many of us stand our ground when it comes to defending the Verum, Bonum, Pulchrum – Truth, Goodness, Beauty? For instance, everyone is quick to criticise a corrupt politician but they mellow in their sight if not melt down at the first sign of trouble. Every one of us has a calling to be prophetic. Jesus shows us the role of prophecy in the church, our churchmen repeat the injunction again and again but how many walk the talk, or simply call spade a spade? There were times when the church hierarchy, from the Pope downwards, authentically stood up to the secular powers and asserted God's law. That had a ripple effect in society and kept it running like a well-oiled machine.

In the Gospel (Mt 10: 26-33), Jesus sends forth His disciples to fearlessly proclaim His doctrine. He promises to expose what is hidden and announce what is merely whispered: He calls us to be upfront about God and His dominion over Creation. However, He cautions His disciples against satanic forces that can destroy body and soul; yet there is none to fear but God who alone has authority over all things. In short, Jesus calls us to be proactive, to acknowledge and stand by Him – for, then, He will stand by us, when we go to our eternal reward. And woe to him who denies Him, for they will be paid back in the same coin.

Expanding the ideas of eternal life and damnation, St Paul in the Second Reading (Rom. 5: 12-15) speaks of how sin and death entered the world through Adam and how humankind was redeemed through the supreme sacrifice of the Second Adam, Jesus Christ. Whereas Adam’s act led to our separation from God and set off our condemnation, Jesus’ Resurrection brought hope of reconciliation with God and ensured our salvation. This is the supreme reality, in the face of which everything else pales out into insignificance.

Today we are invited to examine our lives: to what extent do we believe in the existence of God? How far are we ready to overcome all odds and affirm our faith? To what extent do we trust in the Announcer of the Good News – and in Him alone? Do we suffer from a trust deficit in things that really matter? Or do we at times suffer from overtrust? At any rate, it matters who and what we trust. In the era of fake news, it matters what we finally believe and trust.

At the end of a terrible week that saw Titan go the way of the Titanic, let us realise, before it is too late, that Jesus alone is the Way, the Truth and the Life. When we trust in Him without reserve, there is no titan to fear. Note how the fishing boat trapped in that fierce storm in the Sea of Galilee did not sink as the supposedly unsinkable did the submersible went down in the North Atlantic: rather than the size of the craft or the material used it was the presence of the proverbial Pilot Jesus Christ that made all the difference.

Doctrine to the winds?

It is of the essence to look at Catholic doctrine as one whole; by looking at it piecemeal we may end up distorting it, just as by interpreting it loosely we may sooner or later water it down completely.

Here is a case in point: as seen on Corpus Christi Sunday, Jesus’ words (Jn 3: 16-18) – “God so loved world that He gave His Only Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have eternal life” – mean that outside the Church there is no salvation. And this is what the Catholic Church has taught down the ages.

As pointed out in our reflection last Sunday, the Catechism of the Catholic Church states that “those who, through no fault of their own, do not know the Gospel of Christ or his Church, but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart, and, moved by grace, try in their actions to do his will as they know it through the dictates of their conscience – those too may achieve eternal salvation” (CCC 847).

In short, Baptism is necessary for salvation of anyone who has heard the Good News and has had the possibility of asking for Baptism.

Risk of Concessions

On the other hand, concessions could lead the faithful to believe that anything goes. One such of my worst fears came true yesterday when I happened to attend the anticipated Sunday Mass at a chapel. The priest stated quite nonchalantly: “There is no need for baptism; living the Christian values is enough.”

In one stroke he had let the congregation know that they need not have come to church at all; just living a good life at home or elsewhere would suffice! Should we, then, dismantle our baptismal fonts?

When approached after Mass, the cleric tried to wriggle out from it at first but before long he admitted that his words were meant to appease a certain section… In the process, he had not only taken the congregation but even Our Lord Himself for granted. Thus, in a bid to sound politically correct, he had no qualms about being evangelically incorrect.

Who can deny the possibility of a non-sacramentally baptised person being saved, under the circumstances foreseen by the Catechism? But is it a cakewalk? If salvation of the baptised is difficult – for we have to pass through the narrow door – it is much more so for the non-baptised who have no access to the sacraments and other ordinary means of sanctification that God has provided to his Church!

That is why Pope Pius IX in his encyclical Quanto conficiamur moerore (10 August 1863), on promotion of false doctrines (cf. paras. 7, 8, 9, 11, 13), condemns those who believe that “good hope at least is to be entertained of the eternal salvation of all those who are not at all in the true Church of Christ” (Syllabus of Errors, 1864, para 17)

Newfangled Approach?

When a clarification was sought, the priest waxed eloquent about a “new approach” devised by the Church and, right or wrong, cited the present Pope. But then, the important point to remember is that no approach, whether old or new, is entitled to throw doctrine to the winds.

According to the so-called new approach, then, is the sacrament of Baptism only a dispensable ritual and no guarantor of supernatural life? Or am I to believe that supernatural life is nonexistent, or maybe unimportant, provided we have a good life? And should I stop believing that baptism has made me a child of God and Heaven more easily accessible?

In fact, without Baptism, we would have no access to any of the other sacraments either. More specifically, Holy Orders would be out of bounds: mustn’t priests, then, be in awe of the first Sacrament rather than make slighting references to it?

And what about the priest’s privilege to forgive sins and celebrate Mass? And if there were no Sacrament of Penance, would penitents be able to regain the grace lost through sins?

It is therefore not for nothing that St Paul has said that through baptism we “put on Christ”; and St Thomas teaches that the sacrament “configures” us to Christ!

Pray for Priests

For the above reasons and many more, let us hold the Sacraments in the highest esteem. No better person than the priest, who acts in Persona Christi, to set the example. He should by no means balance himself on the razor’s edge, lest he leave the parishioner confused and demoralised, if he has cared to listen to the homily.

I write this with a heavy heart but in the spirit of “bear[ing] one another’s burdens and so fulfil[ing] the law of Christ” (Gal. 6:1-2). Hence, I would like to end with Pope Benedict XVI’s prayer for Priests:

Lord Jesus Christ, eternal High Priest, you offered yourself to the Father on the altar of the Cross and through the outpouring of the Holy Spirit gave your priestly people a share in your redeeming sacrifice.

Hear our prayer for the sanctification of our priests. Grant that all who are ordained to the ministerial priesthood may be ever more conformed to you, the Divine Master. May they preach the Gospel with pure heart and clear conscience.

Let them be shepherds according to your own Heart, single-minded in service to you and to the Church and shining examples of a holy, simply and joyful life.

Through the prayers of the Blessed Virgin Mary, your Mother and ours, draw all priests and the flocks entrusted to their care to the fullness of eternal life where you live and reign with the Father and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Banner: https://truthout.org/articles/the-shutdown-as-shock-doctrine/

Adoring the Real Presence

All of us at some point or other must have wondered as to why we Catholics consume the Body and Blood of Christ! Today, the Solemnity of Corpus Christi (Latin for “Body of Christ” and short for Dies Sanctissimi Corporis et Sanguinis Domini Iesu Christi, or “Day of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Jesus Christ the Lord”) provides an answer to our concerns. It celebrates the Real Presence of the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus in the Holy Eucharist instituted on Maundy Thursday. On this day, with the shadow of the Cross by now on the liturgy, the Church is at a loss to express her joy at this ineffable gift; hence, a special feast.

This feast has an interesting history. Whereas from the earliest centuries, the Church believed that the elements used in celebrating the Eucharist changed into the Body and Blood of Christ, it was only at the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) that the doctrine was termed as "Transubstantiation". In the year 1226, canoness and mystic Juliana of Liège had visions of Our Lord, who asked her to work towards the institution of such a feast but this happened only twenty years later and only locally. In 1263, at Bolsena, Italy, when a consecrated host that bled onto a corporal at the altar was considered a Eucharistic Miracle, by St Thomas of Aquinas, at his behest Pope Urban IV issued a papal bull Transiturus de hoc mundo (1264) (unprecedentedly) declaring a universal feast: that of Corpus Christi.

However, both before and after this watershed year, there was continued scepticism about the Body and Blood consumed in Holy Communion. Back in Jesus’ time, the Jews considered the very proposal a gross violation of the Mosaic law, but Jesus insisted that only “He who feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood has life eternal, and I will raise him up on the last day.” Early Christians were accused of cannibalism, so much so that, while persecution by Jews and Romans alike was rife, the faithful felt compelled to celebrate the Holy Eucharist in the privacy of their homes or in the catacombs.

Nonetheless, Jesus who is at the centre of all history had to be right. Note how Jesus’ radicality was born with Him in the manger (feeding trough) in Bethlehem (literally, ‘house of bread’), and was confirmed at the Last Supper when He declared unequivocally that He is the Bread of Life. On hearing objections, He did not soften his language but reinforced it. Obviously, taking Jesus at His word, the Church teaches that the Eucharist is not symbolic but real, in fact, “the source and summit of Christian life”. It is said that just as death came into the world by eating the forbidden fruit, eternal life is restored by eating the Bread of Life. If His flesh is food, by the same logic, His blood is drink.

Meanwhile, the First Reading (Deut. 8: 2-3, 14-16) speaks of manna – a perishable bread! Moses told his people that by this God made them know “that man does not live by bread alone, but that man lives by everything that proceeds out of the mouth of the Lord” (which, in the New Testament, is also Jesus’ wise retort to Satan in the wilderness). Moses was only exhorting his people to remember God not only in bad times – when they need His help – but also in good times, when they tended to forget Him.

In the Second Reading (1 Cor 10: 16-17), St Paul too highlights the sublime mystery that is the Holy Eucharist. He shows the sheer incompatibility of the Christian eucharistic feast and pagan sacrificial banquets. The Eucharist is truly sacrificial in nature and bears the Real Presence of Christ. The Apostle of the Gentiles draws our attention to the power of the Eucharist – that “because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of one bread.” The Israelites of old merely consumed the offerings; Christians who consume the Body and Blood of Christ gain eternal life.

Finally, Joan Carroll Cruz's Eucharistic Miracles and Eucharistic Phenomenon in the Lives of the Saints (Tan Books: 1991) and others on the same topic will let us see, concretely, how "real" the Presence is. While the Holy Trinity is a central tenet of our faith, as we saw last Sunday, the Holy Eucharist, being a real communion with Christ, is a central feature of ecclesial life and most worthy of perpetual adoration.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3H5f7oePQE

The Holy Trinity, a deep Mystery!

Close on the heels of Sunday of the Holy Spirit comes Sunday of the Holy Trinity, this latter being the central mystery of our faith and life (CCC 234). We believe in One God, who is not alone, solitary, but a Trinity, a Triune God, a divine family of life and love. As the Father sent His Only Son, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, Jesus Christ, to be born in the world; and, in turn, Jesus Christ, who upon ascending to the Father, made sure that the Third Person, the Holy Spirit, would descend upon the world, it is but natural that we acclaim them all together today – in the Solemnity of the Holy Trinity.

The First Reading (Exod 34: 4-6, 8-9) takes us back to the beginning, to witness Moses’ encounter with God the Father. God rightly introduces Himself as “merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness.” This delightfully accurate self-description so comforts Moses that he promptly invokes his “stiff-necked people” (a true description of the miserable human race) who, by relapsing into idol worship, had provoked Moses into breaking the tablets inscribed with the Decalogue. Moses calls upon God to pardon their iniquity and their sin, and take them for His inheritance, or say, forgive their shortcomings, restore them to health and become beneficiaries of His love.

The Gospel (Jn 3: 16-18) refers to the Second Person, in the words of none other than Jesus Himself: “God so loved world that He gave His Only Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have eternal life.” Here we have an endorsement of God’s love and the promise of eternal life to those who believe in Him. In the words of bishop St Cyprian of Carthage (3rd century AD), salus extra ecclesiam non est, or extra Ecclesiam nulla salus, which means that outside the Church there is no salvation.

So, what about “he who does not believe”, as Jesus put it? God’s love expressed through Jesus – who died to save us – is so great that we lose our salvation if we do not stand by Him and embrace the Faith. This is what the Catholic Church has traditionally taught. The present Catechism of the Catholic Church, quoting Vatican II document Lumen Gentium, explains: “Those who, through no fault of their own, do not know the Gospel of Christ or his Church, but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart, and, moved by grace, try in their actions to do his will as they know it through the dictates of their conscience – those too may achieve eternal salvation.” (CCC 847) Food for thought and discussion beyond the Reading of the day!

The Second Reading (2 Cor 13: 11-13) speaks of the Holy Spirit. St Paul teaches us to greet one another saying, “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all.” Familiar words. That’s how the Apostle of the Gentiles ends his letter to the Corinthians; and that’s how we begin the liturgy of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. So routinely do we pronounce these words that we fail to appreciate their deep meaning.

The fact is that none can claim to have fully understood the Holy Trinity. But, as the Catechism says: “God has left traces of his Trinitarian being in his work of creation and in his Revelation throughout the Old Testament. But his inmost Being as Holy Trinity is a mystery that is inaccessible to reason alone or even to Israel's faith before the Incarnation of God's Son and the sending of the Holy Spirit (CCC 237). The Father is revealed by the Son; the two are revealed by the Spirit (CCC 238-248) The whole divine economy is the common work of the three divine persons. (CCC 258) The ultimate end of the whole divine economy is the entry of God's creatures into the perfect unity of the Blessed Trinity. (CCC 260)

So, how do we proceed from here? Even before trying to delve into the Mystery, we must acknowledge how privileged we are as Christians to have been let into what is indeed the Mystery of the intimate life of God. It is profound, simply overwhelming, incomparable! If we have not fully understood it – and we never will – there is nothing to fear. St Augustine tried to reason out, but to no avail; there is that famous story of how a little child set his questions at rest…. So, out of the mouths of babes...!

On the other hand, what the mind cannot do, our hearts can – faith can! How does a mother understand her baby who only babbles? She does it with love. And that is how, even with reference to everyday things, we may understand the working of the Trinity, "God has left traces of his Trinitarian being in his work of creation". One popularly quoted instance is the flame of fire, which has three attributes (heat, light and shape) and yet is one; and can never be a flame of fire if one of them is missing! The same trinitarian spirit must inspire our domestic life.

Today provides us with an opportunity to meditate upon this fundamental Mystery of our faith and love and to initiate a personal relationship with each of the three Persons of the Holy Trinity!

Pentecost and Proclamation

Today, the eighth Sunday of Easter, we celebrate Pentecost, or say, the fiftieth day after Easter. It marks the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the disciples. The intimate connection between the two feasts will be lost on us if we do not look at its pre-Christian background.

In the old Jewish tradition, the feast of Shavuot was the fiftieth day after the Pesach (Passover). This was held to commemorate the liberation of the Jews from slavery in Egypt. On this occasion, many Jews from countries around the Mediterranean came on pilgrimage and stayed on till the Shavuot. This was at first an agricultural feast (a thanksgiving for the first fruits of the wheat harvest) but later came to be related to the receiving of the Law by Moses on Mount Sinai.

On the other hand, a new tradition began when the Resurrection coincided with the day of the Passover. In fact, the Resurrection replaced the Passover, for precisely by His death and resurrection, Jesus offered the world freedom from death and sin. Similarly, fifty days later, or say, coinciding with Shavuot, Jesus sent down the Holy Spirit upon His disciples. Thus was Shavuot Christianised and called Pentecost, Greek for ‘fiftieth day’.

So much for the relation between the old and the new.

In the first Reading (Acts 2: 1-11), St Luke describes the marvel of Pentecost. The disciples and others were gathered to celebrate Shavuot when there was a rush of a mighty wind and tongues as of fire came to rest on each of them. While the wind represents the breath of God blown into the disciples, the fire represents the courage and enthusiasm that filled the disciples.

Concretely speaking, the Pentecost represents the foundation day of the Church. On this day, Jesus sent down the Holy Spirit to guide and inspire the disciples on their mission to preach the Gospel, just as He had promised them before he ascended to the Father. “As the Father has sent me, even so I send you,” says the Gospel (Jn 20: 19-23; a longer form of which was read on the Second Sunday of Easter).

To effectively carry out missionary work, each member of the community received (and still receives) one or more gifts and charisms. There are seven gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord. Whereas gifts are “permanent dispositions which make man docile in following the promptings of the Holy Spirit” (CCC 1830) given primarily for the purpose of personal sanctification, charisms (e. g. healing) are special gifts given for the common good, or say, the good of the Church (cf. CCC 798 ff).

. Significantly, on the Birthday of the Church, there were people separated by languages, cultures, races and nations (all symbolised by the expatriate Jews present over there): they now formed the new People of God.

So, how important, really, is the Holy Spirit? St Paul, in the Second Reading (1 Cor 12: 3-7, 12-13) says that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except by the Holy Spirit”. It is the same Spirit that fills us with charisms, and lets us serve, each according to our gift. While the charisms and services are varied, it is the same Lord. “To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good.” Which implies that our life must be dedicated to the Truth that is God and to the service of the community.

This community is fundamentally the Church. Jesus is the tree or the body, and, correspondingly, we are the branches or the members. The Holy Spirit keeps us united and drinking of the same belief in the True God.

Can there be any doubt, then, that the Church is a divine rather than a human institution? The Holy Spirit gives it life. The same baptism of fire that the apostles received we too do receive through the Sacrament of Confirmation. The gift of tongues symbolises the fact that the Church goes out to the peoples of the world and adapts to their culture while doing what she has been called to do: most clearly proclaiming Our Lord Jesus Christ and Him alone. That is how intimately the proclamation of the Gospel is related to the Pentecost.

A hymn for Pentecost: https://youtu.be/5GrQJGQWfd8

A Gentleman Judge turns 90

The uproar about who will judge the judge is never about the Judge-with-a-heart. Wouldn’t the world be a poorer place without judges to hear disputes and settle people’s differences? The rhetoric, therefore, is aimed at judges who are unfair, whereas judicial officers who have performed their duties to a tee ought to have our gratitude and praise.

Goa’s judicial system has produced many distinguished judges. Álvaro de Noronha Ferreira, who turns 90 today, is a more recent addition to the roll of honour. After graduating from the Panjim Lyceum, he secured a licentiate in Law, with a specialisation in Political and Economic Sciences, from the historic University of Coimbra. He returned to Goa, in 1957, to serve his land, and did so with distinction, retiring as District and Sessions Judge, in 1993.

The political transition of 1961 impacted the careers of entrants into the judicature. Not only did they have to quickly adapt to a dual (civil and common) law system; for the administration of justice in the initial years, they had to even grapple with dual languages (Portuguese and English). Nonetheless, Dr Noronha Ferreira, or simply, Dr Ferreira, as he is referred to by the older and younger generations of the legal community, respectively, discharged his functions with independence, impartiality, integrity, propriety, equality, competence and diligence (cf. Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct, 2002) – to the satisfaction of litigants, lawyers and the general public.

In a book titled In Black and White, brought out on the occasion of Dr Ferreira’s 80th birthday, lawyers and judges have narrated stories illustrating Dr Ferreira’s qualities of head and heart: his knowledge, realism, poise, and sense of humour. Humility is yet another of his widely recognised virtues. It is on record that, on delivering judgements in open court, he would candidly say to the advocate of the losing side: “Mr X, I am not convinced of your client’s case; if you think I am wrong, do file an appeal.”

That is to say, Dr Ferreira did not pretend to be a know-all; he put the lawyers at ease and conducted proceedings with cordiality and dignity; and the litigants for their part found in his polite, baritone voice a promise of justice delivered without fear or favour. It brought positivity to the courtroom and credibility to the judicial process.

So much for Dr Ferreira’s public persona. Is he any different in his personal capacity? I can say that he is one and the same person – married to the truth! His wife, Satya Costa, who quit her job as an assistant professor of Chemistry at the University of Lisbon, has stood solidly behind him; “clothed with strength and dignity… she speaks with wisdom, and faithful instruction is on her tongue” (Prov. 31:10) Their children, Filipe, a PhD in robotics; Carlos, a gastroenterologist in Lisbon; Teresa, a neurologist with the Goa Medical College; and Jorge, a lawyer practising in the capital city, together with their families, carry on the Noronha Ferreira legacy of truth and public service.

Until his retirement, Dr Ferreira’s other interests, like history, economics, numismatics, music, horticulture, were on the back burner. Thankfully, he has remained an avid reader and engaging conversationalist. Blessed with a fund of anecdotes and a memory for detail, he is a colourful raconteur among family and friends. He is discreet by nature and training but does not fail to call a spade a spade, for instance, when it comes to a point about Goan history or in defence of the common good. A stickler for punctuality, he is always ready to go.

Dr Ferreira comes across as one who has internalised the verum, bonum, pulchrum and, by grasping the mysteries of the human heart, has refined the act of judging. His remarkable resilience springs from his innate trust in Divine Providence in all situations of life. By his rich experience of law and life, he carried out his post-retirement assignment as chairman of the Goa Public Service Commission, with wisdom. He has helped with the Lok Adalat, arbitration proceedings, settlement of disputes through conciliation, and gave legal advice to all and sundry who approached him.

Dr Ferreira is a role model for the ages. Thanks to the benchmarks he has set, members of the legal fraternity encourage one another to “be like Dr Ferreira!” A gentleman judge like him is for ever.

Photo credits: Carlos Noronha Ferreira

Ascension: Heaven and Earth drawn near

Even just the last two mysteries of the life of Jesus – the Resurrection and the Ascension – are sufficient to convince us that Jesus is God. The Resurrection shows that Jesus not only rose from the dead but also never died again. In his new, glorified body, Jesus revealed Himself at many locations, over a significant forty-day period. Now, before the apostles’ very eyes, He ascended to His Father, and has been there ever since.

The two mysteries are not only embedded in Scripture, they are recognised by several non-Christian historical sources as well. Even some writers hostile to Christianity attested to the historicity of Jesus and the Resurrection, among them, Stoic philosopher Mara (c. 73 AD) in a letter to his son Sarapion; the Greek-writing Jewish priest Flavius Josephus in his book Jewish Antiquities (c. 93 AD), the influential Roman historian and senator Tacitus in his Annals (c. 116 AD); another Roman historian, Suetonius, in his Lives of the Twelve Caesars (c. 121 AD); and the Talmud (c. 400 AD), a collection of ancient Jewish laws.

If about the Ascension, there seems to be only Scriptural testimony, it is possibly because the eleven apostles alone were privy to the marvel. St Matthew (28: 16-20) and the Acts of the Apostles (1: 1-11) – both of which form the Gospel and the First Reading of today; St Mark (16: 15-20) and St Luke (24: 46-53) (earmarked for Years B and C of the liturgical year) talk about the Ascension. Curiously, the Old Testament too refers to the Ascension, in Psalm 68: 18, a reference that St Paul has used to great effect. In the Second Reading today, we read a passage from his letter to the Ephesians (1: 17-23).

Here is how The Catholic Encyclopaedia describes the glorious Ascension: “Although the place of the Ascension is not distinctly stated, it would appear from the Acts that it was Mount Olivet, since after the Ascension the disciples are described as returning to Jerusalem from the mount that is called Olivet, which is near Jerusalem, within a Sabbath day’s journey. Tradition has consecrated this site as the Mount of Ascension and Christian piety has memorialized the event by erecting over the site a basilica. St Helena built the first memorial, which was destroyed by the Persians in 614, rebuilt in the eighth century, to be destroyed again, but rebuilt a second time by the crusaders. This the Moslems also destroyed, leaving only the octagonal structure which encloses the stone said to bear the imprint of the feet of Christ, that is now used as an oratory.

“Not only is the fact of the Ascension related in the passages of Scripture cited above, but it is also elsewhere predicted and spoken of as an established fact. Thus, in John 6: 63 Christ asks the Jews: ‘If then you shall see the Son of Man ascend up where He was before?’ and in 20: 17, He says to Mary Magdalen: ‘Do not touch Me, for I am not yet ascended to My Father, but go to My brethren, and say to them: I ascend to My Father and to your Father, to My God and to your God.’ Again, in Ephesians 4: 8-10, and in Timothy 3: 16, the Ascension of Christ is spoken of as an accepted fact.

“The language used by the Evangelists to describe the Ascension must be interpreted according to usage. To say that He was taken up or that He ascended, does not necessarily imply that they locate heaven directly above the earth; no more than the words ‘sitteth on the right hand of God’ mean that this is His actual posture. In disappearing from their view ‘He was raised up and a cloud received Him out of their sight’ (Acts 1: 9), and entering into glory He dwells with the Father in the honour and power denoted by the Scripture phrase.”

To positivists and rationalists who may mock the doctrine of the Ascension, the all-important twentieth-century author of Miracles , C. S. Lewis, states interestingly that after the Resurrection, it may have been that Jesus, “a being still in some mode, though not our mode, corporeal, withdrew at His own will from the Nature presented by our three dimensions and five senses, not necessarily into the non-sensuous and undimensioned but possibly into, or through, a world or worlds or super-sense and super-space. And He might choose to do it gradually. Who on earth knows what the spectators might see? If they say they saw a momentary movement along the vertical plane – then an indistinct mass – then nothing, who is to pronounce this improbable?”

In the universality of its observance, the Ascension ranks with Christmas, Easter, and the forthcoming Pentecost. The Ascension completes a glorious cycle which began with the Incarnation; so, it makes perfect sense that Jesus who deigned to come into the world should, at the end of his mission of reconciling man to God, return to the bosom of the Father. His momentous last words on the occasion bear this out. For our part, we must bear Him witness throughout our pilgrim journey on earth, also gratefully acknowledging that, through His Ascension, Heaven and Earth have drawn near.

Banner: https://rb.gy/bahmj

Pondering God’s commandments, with love

As we inch towards the Ascension and Pentecost, we see heartening changes in the incipient Christian community. In the First Reading (Acts 8: 5-8, 14-17), we meet Philip, one of the seven deacons. He is presently in Samaria, where his preaching fell on good soil. The people were in awe of his words and miracles, and relieved on being delivered of evil spirits. On hearing that encouraging update in Jerusalem, apostles Peter and John were dispatched double quick to lay their hands over the Samaritans and pray that they too receive the Holy Spirit.

Samaria awaited a Messiah but was traditionally considered idolatrous ever since a temple to Baal was erected there by King Ahab. So, why was the region suddenly privileged to be in the forefront of evangelisation? Philip had ventured there because Jesus Himself had preached in the area (cf. the story of the Samaritan woman at the well) and wished that the Gospel be taken there after His ascension. Thus, Jesus implied that the Good News of Salvation was meant to reach one and all. It is doubly significant that Philip, not an apostle but a deacon, whose main job was to relieve the apostles of menial chores, became the first foreign missionary in Christian history.[1]

The act of reaching out to Samaria has since had far-reaching implications. The church in Samaria was to Jerusalem what a local church today (say, the archdiocese of Goa and Daman) is to the universal church. The arrangement throws light on the very meaningful hierarchical structure that has governed the Church for the last two millennia; it speaks volumes for the issuance and teaching of doctrine centrally, from the headquarters in Rome, so that all of Christendom is of one mind; and finally, it points to the communion of saints, or say, the fellowship of those united with Christ across space and time.[2]

For Christ to be present with His people across space and time is no mean feat; but to God nothing is impossible. It is a fulfilment of what Our Lord had promised in his farewell discourse, just before His Passion and Death. He had said that after His Ascension, the Holy Spirit would be with the Christians till the end of times; the Spirit of truth would pick up from where He had left off, to illumine and strengthen all the faithful. There is no denying that, inasmuch as we keep the commandments, we grow in wisdom and stature, and live in spiritual unity and love of God. God is then always in our midst.

But, really speaking, who has the strength to keep the Lord’s commandments? Only those who love Him will do so, says Jesus, quite plainly, in the Gospel today (Jn 14: 15-21). Yes, it demands total commitment – difficult, but not unreasonable or impossible. Don’t spouses, children, bosses, friends, clubs, expect the same? Don’t we, then, respect rules and keep promises; and when we don’t, we quit – or are obliged to quit? Why, then, should a relationship with the divine be any different? In fact, our commitment should have been infinitely stronger; but alas, it isn’t, simply because for far too long we have been accustomed to taking God for granted. ‘God will understand’ is a lame explanation, and a convenient ruse to flout rules and break promises.

Concretely, let us look at the First Commandment: "You shall worship the Lord your God and Him only shall you serve." It summons us to believe in God, to hope in Him, and to love Him above all else. "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul and with all your strength" (Deut. 6:5). Adoring Him, praying to Him, offering Him the worship that belongs to Him, fulfilling the promises and vows made to Him are acts of the virtue of religion.

On the other hand, superstition is a departure from the worship that we give to the true God. It is manifested in idolatry, as well as in various forms of divination and magic. Similarly, atheism is a sin against the first commandment, since it rejects or denies the existence of God.[3] Yet, what is the in-thing? To keep God out of one’s day-to-day dealings, if deemed socially and/or politically expedient. This is the antithesis of the First Commandment that we are expected to profess and practise; what the score will be on the remaining nine is anybody’s guess!

St Peter in the Second Reading (1 Pet 3: 15-18) therefore counsels us to revere Christ as Lord; defend those who are on God’s side; do the right thing, in the right way, so that none can point an accusing finger at us. “For it is better to suffer doing right, if that should be God’s will, than for doing wrong,” he adds. We ought to muster courage by summoning up the memory of Our Lord’s undeserved death for our sins. As regards us, we run the risk of being hated or even put to death for siding with God, but we may rest assured that we will be made alive in the spirit by the same God who has conquered sin and death: Jesus Christ our Lord.

A tall order? If we listen to God’s commandments – with our minds and hearts – pondering what they mean to us here and now, we will invariably be assisted by the Holy Spirit. As Jesus has cautioned, the dark world of unbelief is incapable of understanding and accepting the Spirit of truth – which will be accessible only to those who love and revere Him!

[1] Philip famously converted an Ethiopian eunuch, thus inducting a black into the church at a very early stage. Then he proceeded to evangelise other areas up to Caesarea; Greece, Syria and Phrygia.

[2] Those living are said to constitute “the church militant”, while the dead who are in Heaven, “the church triumphant”, and those in Purgatory, “the church suffering”. Yet the three groups are in communion of the Spirit.

[3] Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P7G.HTM