Where are the Fishers of Men?

On the third Sunday in Ordinary Time, Isaiah points to Our Lord as the Light of the World; St Matthew recounts the first days of Christ’s ministry in the wake of the arrest of St John the Baptist; and St Paul exhorts the Corinthians to remain one in mind and heart.

In the First Reading (Is 8: 23 – 9: 3), God in His goodness promises to break “the yoke of [Israel’s] burden, and the staff of his shoulder, the rod of his oppressor”: He would let it triumph over the Assyrians, as He had done against the Midianites, using men armed with clay pots, torches and trumpets!

However, what Isaiah said about Zebulun and Naphthali[1], both located in Galilee, is even more significant. This region had a large, non-Jewish, immigrant population; hence it was called “of the Nations” or “of the Gentiles”. Although the Galileans were considered of dubious ancestry, uneducated, and seditious, they were in fact more faithful to God than others who worshipped false gods. God rewarded Galilee by allowing it to host the Lord of lords and King of kings, who would be a Light to the Nations.

In the Gospel (Mt 4:12-23) we see the realisation of the Isaian prophecy. Bethlehem, where Jesus was born, and Nazareth, where He grew up, were towns in Galilee. It was here that Jesus undertook His three-year ministry. Upon John the Baptist’s arrest, Jesus settled in the fishing village of Capernaum, “in the territory of Zebulun and Napthali”. He soon attracted Peter and his brother Andrew, James and his brother John, all humble fishermen, whom he would make “fishers of men”. And “He went about all Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and preaching the gospel of the Kingdom and healing every disease and every infirmity”. He urged them to “Repent, for the kingdom of Heaven is at hand” (Mt 4: 17), thus establishing a link with the teaching of His Forerunner.

But what is “repentance”? And is the kingdom of Heaven still “at hand”? Repentance is a change of mind and heart; it is a flight from sin to God. On the other hand, hardening our hearts to God’s call is tantamount to playing into the devil's hands. “The kingdom of God [or ‘of Heaven’, to the Jews] means, then, the ruling of God in our hearts; it means those principles which separate us off from the kingdom of the world and the devil; it means the benign sway of grace; it means the Church as that Divine institution whereby we may make sure of attaining the spirit of Christ and so win that ultimate kingdom of God where He reigns without end in ‘the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God’ (Rev. 21: 2).”[2]

Thus, repentance and the Kingdom of God are not passé but vital to our everyday life. They must be at the top of our minds, especially considering that enemies of the Church are lurking in the shadows. It may come as a shock – but it is a fact – that Rome is under siege, and so are you and I. Vatican observers state that the highest authorities, enchanted by the world, are playing into the hands of the evil one. Such reports are dubbed ‘conspiracy theories’ by those who wish to anaesthetize us.

However, who can deny that idolatry, indoctrination, deception, division, and demoralisation are the handiwork of the devil? That theological errors abound, moral teaching is being undermined, and tragically, inter-religious ecumenism is being given the advantage over evangelisation, are signs of the times. If this is not the self-demolition that Pope Paul VI spoke of half a century ago, what is?

The situation has never been so bad. Therefore, what St Paul said in the Second Reading (1 Cor 1: 10-13, 17) is now relevant to a much higher degree: we must be “united in the same mind and the same judgement.” In the early days, philosophical schools caused discord; in our day and age, Humanism borders on the very denial of God.

On the other hand, in these trying times, where are the “Fishers of Men”? To neutralise nefarious influences, it is essential that the powers that be uphold the Apostolic Tradition, that is, “the transmission of the message of Christ, brought about from the very beginnings of Christianity by means of preaching, bearing witness, institutions, worship, and inspired writings. The apostles transmitted all they received from Christ and learned from the Holy Spirit to their successors, the bishops, and through them to all generations until the end of the world.”[3] That is what true Fishers of Men ought to do, Ad Gentes: to the nations.

[1] Names of two of the twelve sons of Jacob who eventually formed the twelve tribes of Israel; they were brothers of Joseph, whom some of the siblings sold into slavery into Egypt, because they hated him. Only the tribes of Judah and Benjamin survived.

[2] Pope, H. (1910). Kingdom of God. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved January 20, 2023 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08646a.htm

[3] https://www.vatican.va/archive/compendium_ccc/documents/archive_2005_compendium-ccc_en.html (Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Part One, Chapter two, question 12)

Banner: https://www.wallpaperflare.com/man-standing-on-boat-throwing-net-backlit-dawn-dusk-fisherman-wallpaper-alxue

A Noiva

January 20, 2023Translation,Short Story

Vhokol - um conto de Olivinho Gomes traduzido por Óscar de Noronha - A Noiva

As férias judiciais atrasam os trâmites dos processos. Igualmente, o tabelião da comarca fica atarefado com montes de escrituras e doações, a distribuição das diligências e a sua devida passagem para o papel na forma legal deixa o pessoal muito atarefado.

Os tribunais haviam reaberto apenas na véspera. E numa cidade como Margão, onde o meu cartório era o único, estava eu ocupadíssimo, como sempre, quando se deu o incidente que ora vou contar.

Devia ser por volta do meio-dia e meio. Logo em frente ao meu cartório parava um carro do qual saía um cavalheiro jovem e janota. Veio pressuroso até a minha porta e pediu-me licença para falar. Notando esse quê de urgência, disse-lhe que entrasse.

Tendo ouvido tudo o que me contou, vi-me obrigado a interromper o trabalho e acompanhá-lo. Em poucos minutos, contou-me a história de uma senhora, que disse ser sua prima direita. Vivia enclausurada em casa e ora desejava lavrar a declaração da sua última vontade. Como não regulava bem, era necessário cumprir de imediato o seu desejo, de contrário enfurecia-se e era capaz de tudo. Queria ela que eu viesse urgentemente à sua casa.

Fui com Caetano, de carro. A casa situava-se num bairro interior da aldeia da Raia. Levou-nos meia hora a percorrer esse caminho, de voltas e reviravoltas, para chegar ao destino.

Como é que descrevo essa habitação? Não era uma simples casa; era um palacete. Sabe Deus de que século! E parece nunca ter sido tratada. Estava bem nos tempos passados uma construção embrenhada no meio de árvores de teca. Ora, via-se pedaços do reboco de cal caídos no chão, que deixavam expostas as pedras vermelhas. O resto da casa estava às escuras, parecendo prestes a ruir.

Subimos a escadaria meia quebrada e com limos. Caetano gritou por alguém. Apareceu então uma empregada, que trazia na mão uma vela acesa. Com as janelas todas fechadas, era escuro o interior do casarão. Eu, levando a pasta na mão, e com o mínimo de falas, fui pela casa adentro, junto com Caetano, à luz dessa vela.

Caetano arredou a cortina dum compartimento, que não era muito grande; deu-me para passar aí uma rápida vista de olhos. Quando me dei conta da situação, caiu-me o coração aos pés. Nessa casa, toda fechada, ficavam acesas o dia inteiro as velas dos candelabros da parede. Sobre uma mesa lá no canto estavam colocadas umas coisinhas. Aqui e acolá, estavam dispersos frascos de perfume, ganchos de cabelo, pentes, toalhas, lenços, espelhos... e numa cadeira encontrava-se sentada uma senhora, que fitava, murcha, e vestida de branco. Era o traje do seu noivado, que com o tempo se tornara amarelado, desbotado, manchado. Tinha aliás, o seu rosto, crestado pelas rugas, empoado. Calculo que ela não devia passar dos quarenta e tal anos. À sua volta, as aves haviam construído ninhos cobertos com as suas penas.

Apesar de ter entrado no quarto com Caetano, em bicos dos pés, os meus passos causaram-lhe sobressalto. Os seus olhos arredondados, sempre a fitar, mediram-me. Embora parecesse aliviada com a minha chegada, abriu ainda mais os olhos e, de súbito, soltou uma gargalhada danada, e gritou:

- Ha... ha… ha… lá vem o meu noivo. É esse mesmo, esse mesmo. É com ele que me vou casar. Vem ao pé de mim, meu senhor, meu amor. Estou à tua espera, ha… ha… ha...

Cobri-me de suor frio ao ouvir esse riso louco que me eriçou o pelo. Fiquei de alerta. A minha longa experiência de advogado e tabelião público não permitiria que me deixasse levar pela emoção. Ainda assim, senti-me um tanto atrapalhado e com a língua presa.

Procurei acalmar-me, e depois de me recompor, interpus as mãos dela nas minhas, e disse, carinhosamente:

- Não se preocupe, D. Rosa, sou o notário Armando Gomes da Costa. Diga-me, por favor, o que pretende; não se atrapalhe…

Mal ouviu essas palavras, mudou de semblante. Corou, e já não parecendo a mesma, segredou a sua vontade: a de passar as suas propriedades para o nome de Caetano, seu primo direito. Nada disse sobre o porquê e como. Autorizou-me a consultar Caetano. E disse terminantemente que queria que eu lavrasse aí e agora o seu testamento…

Ainda bem. Estava morto por sair da sua presença. E fi-lo juntamente com Caetano.

Sentámo-nos num quarto lá dentro. Na verdade, todos os compartimentos eram lúgubres, porém, este era melhor do que os outros, pois tinha pelo menos uma janela aberta. Logo que nos sentámos, a empregada serviu-nos o almoço e a seguir Caetano contou-me a história da sua prima Rosa.

Rosa Esmeralda das Dores da Silva, filha única, foi alvo do carinho e amor dos seus pais. Era bem-parecida, prendada, inteligente e afectuosa. Aos dezasseis anos de idade, passou no exame de acesso à universidade, seguindo depois para Bombaim para prosseguir os estudos superiores, pois, na altura, não havia colégios universitários em Goa. Era então uma moça que dava nas vistas; não havia rapaz que não se sentisse atraído por ela. Por outro lado, ela não caía por todo e qualquer, nem era de dar muita confiança.

Em Bombaim, matriculou-se no National College, de Bandrá, e fixou moradia na casa de algum conhecido. Em pouco tempo circulava o seu nome pela boca do povo. Era a primeira aluna da turma; como dançarina, não havia igual; e na beleza, era deslumbrante. Muito moço havia estalado os lábios. Como regra, escrevia para casa pelo menos quinzenalmente.

Sucedeu que, após uns sete ou oito meses, uma carta sua entristeceu os pais. Estes, porém, não tinham a coragem de contrariar a filha. Eis o que Rosa lhes escreveu: que viera a conhecer um simpático moço com quem andava enamorada. O rapaz era oriundo do norte da Índia, provavelmente, do Punjabe. As cartas dos seis meses que se seguiram só contavam maravilhas do rapaz: dos bailes a que assistiram, das praias balneares que frequentaram, dos filmes que viram; ao mesmo tempo que pedia novas remessas de dinheiro.

Passado algum tempo, chegava uma carta ainda mais triste. O rapaz, deixando o colégio e a cidade de Bombaim, regressara à sua terra natal, sem a Rosa saber a quantas andava. Numa palavra: ele a havia deixado. Correu ainda que Rosa pretendera suicidar, tendo alguém impedido de o fazer. Foi quando o pai foi buscar a filha de Bombai, e ela passou o ano inteiro em casa. Era manifesta a mudança que sofrera: já não tinha a antiga alegria de viver. Até parecia cansada da vida!

Apesar disso, daí a tempos, com renovado entusiasmo, regressou a Bombaim. Criou novas amizades. Aliás, era esse o seu intuito: travar novas relações, que, na verdade, teve com vários. Parecia-lhe de todo impossível deixar a vida da paródia, a que estava já habituada. Uma vez adquirido um hábito, sobretudo mau, ele torna-se um vício. Mas no meio de toda essa vida desregrada nunca teve sequer um cheirinho da felicidade, pela qual estava sequiosa depois do malogro do seu primeiro amor. Há rapazes que estimulam as emoções femininas, aproveitam-se delas, para no fim as deixar desapontadas. Ser vítima de semelhante infortúnio é o flagelo da moça. Por outro lado, quanto mais ela se defende de tais ciladas, mais cresce a estima e a consideração das pessoas. Mas, no verdor da juventude, poucos se apercebem disso, como também não conseguem discernir entre a paródia ingénua e a maliciosa.

Não deixei que continuasse o sermão.

- Tudo o que diz é pura verdade, senhor Caetano. Mas a mim interessam só os pontos essenciais, ou seja, os passos principais da vida dela. Conte-me só isso, pois quero avançar o testamento. Se não, ela lança-se contra mim…

- Peço desculpa, senhor doutor! Como dizia… é verdade.... – continuou Caetano, retomando o fio da história:

- À Rosa apetecia lançar o barco da vida no alto-mar, sem vela, nem remos, nem leme, ao mesmo tempo que, no meio das águas tumultuosas, procurava ancorar nalgum porto. Por fim, com vista num moço, escreveu a dizer: este é o meu noivo de certeza. Correu que era de Mapuçá; rapaz bem posto, de boas famílias.

O rapaz veio até a Raia para se apresentar aos pais de Rosa. Saiu aprovado. Foi marcado o casamento para daí a um ano, a 15 de janeiro de 1943.

Rosa regressou de Bombaim um mês antes do casamento, tendo completado o bacharelato em letras. Sentia-se tranquila, esperando passar alegremente o resto da vida na companhia do marido. Seria uma vida despreocupada, pois a riqueza da família lhes bastava para mais duas gerações. Importava-lhe apenas deixar o passado e pôr os olhos na construção do futuro. O noivo estava em Bombaim; e, em Goa, talhavam-se as roupas de casamento. Entretanto, o noivo anunciou por carta que chegaria no dia 13, o que deu lugar a dias de grande alegria para todos.

Quando viram que estava iminente o casamento da amimada filha única do batecar, também os manducares do prédio rural deram início a festejos. As suas vojem, dennem e denngui – consoadas – encheram a casa do proprietário. Como o pai da noiva já não pertencia aos vivos, os manducares mais velhos tomaram sobre si os arranjos do casamento, o que facilitou bastante a vida da bhattkan.

Quando o noivo veio à Raia, todo o prédio se encheu de contentamento. Encontrou-se com a noiva, com que acertou tudo: daí a dois dias iam-se casar, sendo a missa às dez da manhã, na igreja da Raia. Assente isso, declarou que seguia a Mapuçá.

Continuaram os preparativos pela noite fora. A manhã do casamento raiou no meio de alegre bulício. Minha prima direita, ora uma bela recatada, que vestira com grande ânimo o seu traje de noiva, estava já pronta. Que linda que ela parecia no seu vestido, bem-talhado e engomado, branco como a neve! Era o seu dia de maior júbilo. E chegou a hora da saída…

Ora, devia faltar um quarto para as dez. Aparecia o carteiro com um telegrama que tomámos como de felicitações. Era para a Rosa. Fui eu a abri-lo e logo ela o arrancou da minha mão. Mal o leu, de acabrunhada pôs-se a dar socos no peito e a chorar aos brados. Estava estonteada; revirou os olhos; começou a tremer; desmaiou, e antes que a segurássemos, caiu ao chão.

O telegrama dizia o seguinte: “Não posso vir ao casamento. Esqueça-me.” O remetente: Eduardo (nome do noivo). Trazia o endereço de Bombaim. E que remédio, se uma traição dessas estava reservada à minha prima direita!

Quando voltou ao siso, Rosa não pôde mostrar a sua linda cara. Estava fora de si. Desde então tem estado encerrada nesse quarto fechado, com a mente também fechada. Mesmo assim, não perdeu a esperança que tinha no seu noivo. Todo e sempre, vestida de mulher prometida em casamento, tem estado à sua espera. Até hoje. Toma banho em dias alternados e traja o mesmo vestido de noiva, e, toda empoada, fica aí sentada a essa mesa e a aguardar a chegada do noivo. De facto, está fora de si. Às vezes, num ímpeto, levanta-se e põe-se a andar; brama ou guincha, fala em voz alta, ou à toa. Só Deus sabe que pensamentos a atormentam! Desse noivo cruel, porém, nunca mais se soube o paradeiro. No meio dessa chocante marcha de eventos, morreu-lhe a mãe, ficando Rosa sozinha, a chorar as mágoas da vida. Dêmos graças a Deus que ela não tenha suicidado, embora a vida lhe tenha sido um lento suicídio.

Com essas palavras, terminava Caetano essa história dramática, que me golpeou o coração. O desgosto da Rosa tornou-se meu também. Ninguém sabe o que pode resultar das nossas acções e quão amargo pode ser o fruto: só de pensar nisso quase que me ia passar despercebida a diligência que ali me havia levado.

Não lhe consegui lançar novamente um olhar. Estava eu a verter lágrimas. Que rapariga modelar, educada num ambiente de alegria, e que ora se encontrava nesse infeliz emaranhado da vida! Haviam-se passado anos e ela envelhecera prematuramente. Não se podia prever a hora em que apagaria essa vela mortiça, deixando a casa às escuras. Por isso, almejava ela reavivar essa vela, o que tornava urgente esse testamento.

Lavrei rapidamente o testamento e com gentileza obtivemos a sua assinatura. E travando a catadupa de lágrimas, com um coração pesado e a mente reflectindo sobre as malhas da vida, saí do sítio o mais depressa possível. Ficou, porém, comigo a imagem triste dessa eterna noiva que nos tempos que já lá vão foi tão bela: ela destroça-me o coração e me persegue eternamente.

Notas Biográficas

Olivinho Gomes (1943-2009) foi concanista de renome, alto funcionário público, e, mais tarde, professor catedrático de concani, na Universidade de Goa. Autor de mais de 40 livros, poeta, contista e tradutor, verteu a Mensagem de Fernando Pessoa e Os Lusíadas de Luís de Camões para a língua concani, respectivamente, sob os títulos de Sondex e Lusiyatonn.

Traduzido do concani e publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 20, Jan-Fev de 2023

Primordial Light

Last Sunday marked the Baptism of Our Lord. Historically, Jesus began His public ministry after His Baptism at the age of 30. Therefore, it is only fitting that the readings of the second Sunday should touch upon the primordial light of Christianity.

In the First Reading (Is 49: 3, 5-6), who is that “Servant” chosen to unite the scattered tribes of Israel and to enlighten the world with His Word? The Old Testament refers to several as “Servants of the Lord”: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Joshua, Isaiah, Job, Nebuchadnezzar, and even God’s chosen people, Israel, often called 'Jacob'.

While it is no wonder that that title should refer to Israel, it has eventually come to represent Jesus Christ more specifically: “I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth.” Although he was “crushed for our iniquities,” as Isaiah had said (cf. Is 53) that he would be, Christ accomplished His salvific mission. Christianity is the world’s largest and most widespread religion, with over two billion followers representing one-third of the world's population. However, since the light of divine revelation is still waiting to envelop the world, there is no room for complacency. Rather, it behoves us to be God’s instruments and say: “Here I am, Lord! I come to do Thy will.” (Ps 40)

In fact, it is the vocation of every Christian to walk in the footsteps of Christ and do His will without fear or favour. If God is for us, who can be against us? (Rom 8:31) The Psalm teaches us that He is always by our side, stoops down to us, hears our cry, and turns our cry into a song. What is more, He asks not for sacrifice and offerings but for a listening ear and a willing heart. If we only delight in His law from the depth of our hearts – where God’s law is engraved – we will see that He is our only hope and salvation, and proclaim His justice in the great assembly.

In this regard, St Paul set a noble example to all generations in the Second Reading ((Cor 1: 1-3). In his self-introduction to the Corinthians, he announced that God had called him to be an apostle. He dared to establish a community in a city steeped in corruption and urged sinners to become saints. Thus, the local church of Corinth was a symbol of the creation of the universal Church. He warmly encouraged his people to persevere in holiness, for God is holy. What a lesson to be learned by those who easily get discouraged and begin to falter!

Holiness is a sweet challenge, and only a life of faith, hope, and charity can help us attain it. To this end, we must be alter Christus, ipse Christus – another Christ, Christ Himself! St John the Baptist, who knew the path to salvation, never ceased to say, ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord’. Although he was unworthy to untie the Lord’s sandals, he baptised Him in the Jordan, “that He might be revealed to Israel”.

Interestingly, Jesus and John, though close relatives, did not know each other closely; one had grown up in Galilee and the other in the desert. Nonetheless, John instantly saw that Jesus was the Messiah when the Holy Spirit descended and remained on Him, as preannounced to him by the Heavenly Father.

“The Holy Spirit had rested upon Jesus, not only to bear witness outwardly to the grace which abounded within Him, but to exercise an active influence over Him,” says the Abbé Constant Fouard in his classic work La Vie de N.S. Jésus-Christ (1880). “And therefore, so soon as the Christ had received this consecration He was ‘led by the Spirit’, St Matthew recounts; ‘led on into the wilderness,’ says St Luke; ‘sent out’, borne away, driven ‘into the desert’, according to St Mark”[1]. Over there, as is well known, the Son of God emerged eminently triumphant from a threefold attack waged by Satan. We should also marvel at how He emerged unscathed, “for having taken no part in the perversion of our humanity”[2].

On Jesus’ return from a forty-day stay in the Judean wilderness, where he had prayed and fasted, in close preparation for His public ministry, St John the Baptist saw Jesus coming toward him. It was here that the Precursor presented Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world, as revealed in today’s Gospel (Jn 1: 29-34) tells us. To the Jews pursuing John, it was evocative of the oracle uttered by Isaiah: “The lamb standing dumb before his shearers, the Man of Sorrows, Who shall bear the sins of the people” (Is 53: 3). In other words, John was referring to his cousin Jesus as the One who would be immolated on the Cross, not as a mere symbol of the traditional paschal lamb.

“And I have seen and borne witness that this is the Son of God,” the Baptist stated very confidently. Should not you and I too respond to the primodial light of our own baptism and bear witness to Jesus Christ, that He may always be “a light to the nations” and His “salvation may reach to the end of the earth”?

[1] Cf. Jesus Christ the Son of God, by Abbé Constant Fouard, translated from the French by George F. X. Griffith; published by Longmans, Green & Co. and reprinted by Don Bosco, Goa, 1960, p. 83.

[2] Op. cit., p. 84.

Choques e Surpresas Culturais | Culture Shocks and Surprises

Editorial*

Enquanto vos saudamos pelo Ano Novo, também vos agradecemos o apoio à Revista da Casa de Goa, que traz novidades, também na presente edição!

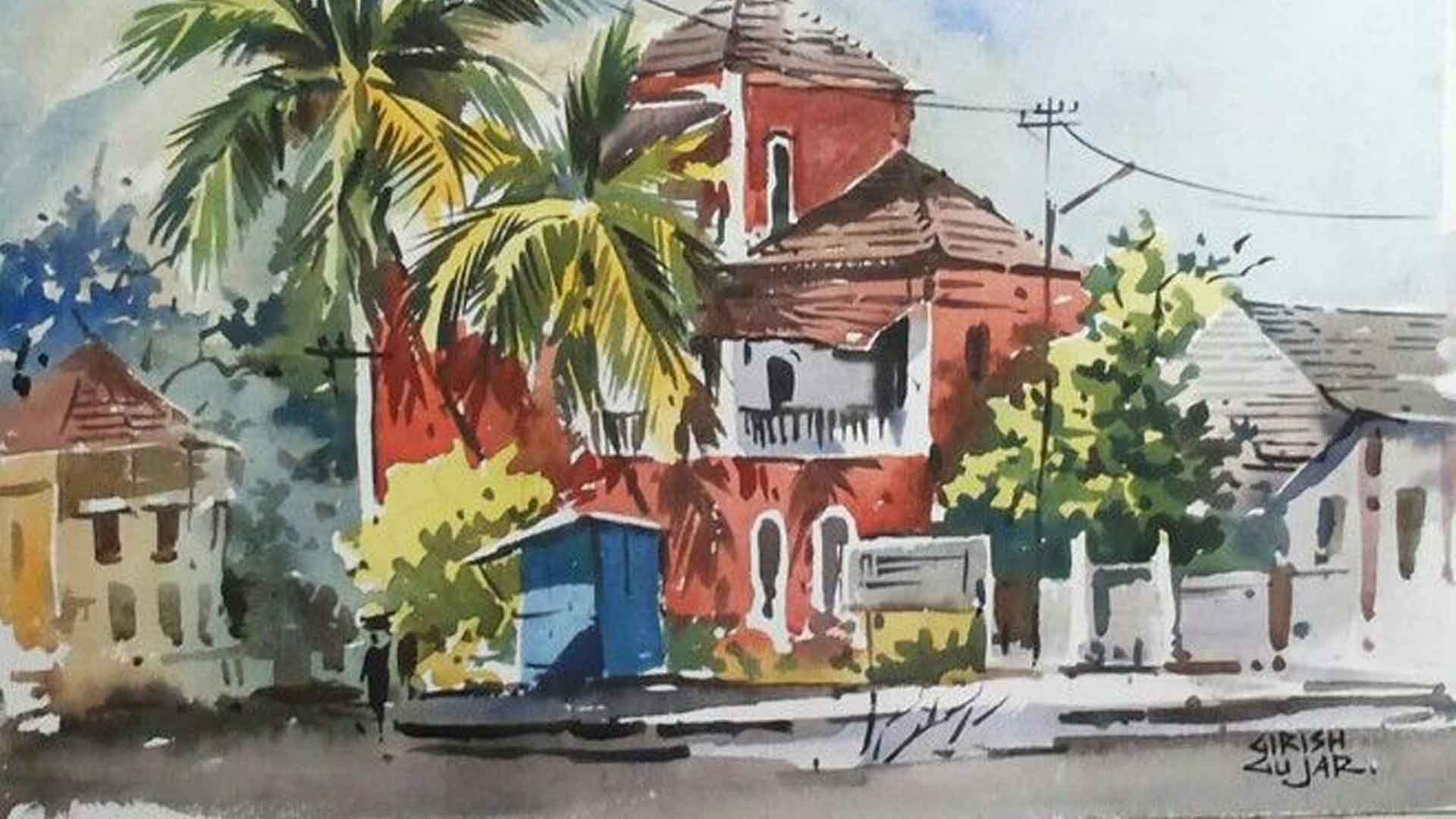

Neste número é inaugurada uma secção de Arte, com a colaboração de três residentes de Goa, os primeiros dois oriundos da União Indiana: Payal Kakkar, artista fotográfica, que explora temas desde o património arquitetónico até a paisagem e conservação do meio ambiente; Girish Gujar, aguarelista e professor de arte; e Clarice Vaz, que ora passa a ser nossa colaboradora residente. A todos três, as nossas boas-vindas!

Ao exímio trabalho desses três artistas que focam o legado artístico de Goa juntam-se, sem ter sido este o intuito, dois dos nossos colaboradores regulares, Francisco da Purificação Monteiro, que disserta sobre as igrejas de Diu, as quais apelida de “património esquecido, em grande estado de degradação”; e Mário Viegas, que se refere à casa de um dos mais célebres Deputados às Cortes Portuguesas, Francisco Luís Gomes: “um imóvel quase abandonado”. São como que as últimas novidades da cultura luso-indiana.

Esse estado de coisas leva-nos a questionar a política cultural dos dois países, a Índia e Portugal. Deixemos por ora a gerência interna e falemos do intercâmbio: teriam sido sinceros os Acordos assinados pelas duas partes? Continua a haver a necessária vontade política na execução das multifárias convenções? Porque tanta assincronia a causar choques culturais? É claro que urge repensar as iniciativas oficiais, sendo ainda mais importante atentar ao nosso modo de pensar, e, em particular, aos princípios e opiniões dos nossos intelectuais ou académicos sobre o assunto em apreço.

Nesse sentido, é imprescindível a leitura do ensaio intitulado “Será a cultura GEM vítima de disparate académico?” Philomena e Gilbert Lawrence analisam discursos académicos rivais em relação à cultura colonial de Goa, East India e Mangalore (daí o acrônimo GEM), territórios outrora sob a égide de Portugal. Apontam para autores lusocêntricos, “que glorificam o imperialismo colonial e exageram o impacto colonial positivo no ethos dos nativos”; os indocêntricos, que “demonizaram o imperialismo colonial e exageraram seu impacto negativo nas práticas culturais dos nativos”; e os goanocêntricos, que “têm uma visão mais amena da colonização e descrevem os colonizadores como “benfeitores e pragmáticos”.

Num mundo globalizado em que não é estranho nutrir uma perspectiva mesclada, o livro intitulado Um estranho em Goa, do escritor angolano José Eduardo Agualusa, é objecto de um ensaio de Júlia Serra, que se surpreende com “esse registo cruzado de elementos, provenientes de culturas e histórias diferentes”; e fala de Goa na lusofonia, a qual continua “em reconstrução de uma identidade”, num caminho sem fim.

Temos ainda o ensejo de apreciar mais um ponto de vista sobre a relação luso-goesa, na crónica “Uma passagem por Portugal”, de Radharao Gracias, que, na sua primeira visita ao país nota paralelos com Goa e enaltece as qualidades dos dois povos que mutuamente se enriqueceram. Enquanto Gracias canta um hino ao Pastel de Nata, será que, para sobremesa, também vos ofereço “A Noiva”, um conto em concani, de Olivinho Gomes, em tradução de Óscar de Noronha? Mas, cautela, ficou comigo “a imagem triste dessa eterna noiva que nos tempos que já lá vão foi tão bela: ela destroça-me o coração e me persegue eternamente”.

Se, por um lado, visitantes goeses encantam-se com Portugal, por outro, duas crónicas nesta edição indicam como os emigrantes goeses se comovem quando de visita a Goa. Armand Rodrigues, que do longínquo Canadá visitou a terra dos seus antepassados, descreve um resort único em Goa, o qual tem à testa “um goês que se mudou conscientemente do seu lar adoptivo em Vancouver para a casa ancestral de sua família, transformando-a em um jardim do Éden em miniatura”. Queiram conhecer esse local idílico em Loutulim, aldeia no sul de Goa; e depois, “vagueando pelas terras do Norte”, na companhia de Mário Viegas, conheçam, entre outros locais, Arambol, uma das praias do hipismo, e o histórico Forte de Tiracol.

Na “Rota aérea para o Paraíso”, desfrutamos de uma vista panorâmica de Goa dos anos sessenta: através dos olhos de Ralph de Sousa, testemunhamos o boom do turismo, a chegada dos hippies e de voos fretados vindos da Europa directamente para o aeroporto de Dabolim, no concelho de Mormugão, o qual, diga-se de passagem, com a vinda do novo aeroporto em Mopa, no concelho de Perném, está a viver os seus últimos dias.

Na secção de entrevistas, Ruta Vedpathak Borkar conversa com cinco goeses que estudaram na Universidade de Puna, dantes conhecida como a Oxford do Oriente. E, para terminar, a secção de Notícias fala-nos das actividades do Ekvat, grupo de danças e cantares da Casa de Goa; de um lançamento de livro da autoria de Francisco Xavier Valeriano de Sá, sócio da Casa de Goa; e de “O Clube”, documentário da autoria de Nalini Elvino de Sousa e Pedro Pombo, o qual retrata a vida da diáspora goesa na Tanzânia. Aproveitamos para vos pedir mais informações sobre o que se passa na vossa área de residência ou de trabalho, sobre a temática Goa-Portugal. E continuemos a reflectir sobre os caminhos que poderá vir a percorrer a cultura luso-goesa.

* Texto revisto. Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 20, Jan-Fev 2023

Editorial*

Let me extend New Year greetings to all you dear readers and thank you wholeheartedly for supporting Revista da Casa de Goa, which comes to you with news and views in yet another edition!

This issue carries an Art section, thanks to the collaboration of three residents of Goa, the first two being settlers here: Payal Kakkar, a photo artist exploring themes ranging from architectural heritage to landscape and environmental conservation; Girish Gujar, watercolourist and art teacher; and Clarice Vaz, who is now a resident contributor. To all three, a hearty welcome!

Unwittingly, these three excellent artists who focus on the artistic legacy of Goa are joined here by two of our regular writers, Francisco da Purificação Monteiro, who writes about the churches of Diu, dubbing them “forgotten heritage, in a great state of degradation”; and Mário Viegas, who refers to the “almost abandoned property” of one of the most famous of the Goan Deputies to the Portuguese Parliament, Francisco Luís Gomes. They are like the latest shocks of Luso-Indian culture.

This state of affairs leads us to wonder about the cultural policy of India and Portugal. Leaving aside their domestic policies for the moment, let us talk about their high-level exchanges: how sincere were they when they signed agreements? Is there still that much-needed political will to implement those varied conventions? Why the asynchrony causing culture shocks? It is imperative to reassess official initiatives, and even more so, pay attention to our rationale, and, in particular, to the principles by which our intellectuals or academics are guided and the opinions they hold on the subject.

In this regard, the essay titled “Is GEM culture a victim of academic baloney?” is vital. Philomena and Gilbert Lawrence analyse rival academic discourses on the colonial culture of Goa, East India and Mangalore (hence the acronym GEM), territories once under the aegis of Portugal. They point to Lusocentric authors, “who glorify colonial imperialism and exaggerate the positive colonial impact on the natives’ ethos; Indocentric authors, who “demonized colonial imperialism and exaggerated its negative impact on the natives’ cultural practices”; and the Goacentric authors, who “have a kinder view of colonization and describe the colonizers as “benefactors and pragmatic”.

In a globalized world where it is not strange to nurture a mixed perspective, the book entitled A Stranger in Goa, by the Angolan writer José Eduardo Agualusa, is the subject of an essay by Júlia Serra. She is surprised by “this cross register of elements, coming from different cultures and histories”; and speaks of Lusophone Goa, now on the endless path of reconstructing its identity.

We also have the opportunity to appreciate another point of view on the Luso-Goan relationship, in “A Passage through Portugal”, by Radharao Gracias. On his very first visit to the country, he notes parallels with Goa and praises the qualities of the two peoples that have mutually enriched each other. While Gracias sings a paean to Pastel de Nata, for dessert may I also offer you “A Noiva”, a short story in Konkani, by Olivinho Gomes, translated into Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha? But, please note, “the sad image of that eternal bride who in times gone by was so beautiful remained with me: she breaks my heart and haunts me eternally”.

If, on the one hand, Goan visitors are enchanted by Portugal, on the other hand, two features in this issue show how Goan emigrants are moved on their visit to Goa. Armand Rodrigues, who from faraway Canada visited the land of his ancestors, describes a unique Goan resort headed by “a Goan who has consciously relocated from his adopted home in Vancouver, back to his ancestral family home, which he has transformed into a miniature garden of Eden.” Please visit this idyllic spot in Loutulim, a village in South Goa; and then, “wandering through the North”, in the company of Mário Viegas, you will get to know, among other places, Arambol, a public bathing beach, and the historic Fort of Tiracol.

In “Skyway to Paradise”, we enjoy a panoramic view of Goa: through the eyes of Ralph de Sousa, we witness “the tourism boom that started in the early sixties, with hippies coming and followed by chartered flights arriving from all over Europe directly to Dabolim airport,” situated in the taluka of Mormugão; which, with the coming of a new airport at Mopa, in Pernem taluka, is now on its last legs.

In our Interview section, Ruta Vedpathak Borkar chats with five Goans who studied at the University of Poona, once known as the “Oxford of the East”. And in the News section we hear about the activities of Ekvat, Casa de Goa’s song and dance group; a book launch by Casa de Goa associate Francisco Xavier Valeriano de Sá; and “O Clube”, a documentary by Nalini Elvino de Sousa and Pedro Pombo, which portrays the life of the Goan diaspora in Tanzania. We take the opportunity to ask you for more information about what is going on in your area of residence or work, focussed on the Goa-Portugal theme. And let us continue to reflect on the paths that Luso-Goan culture could eventually take.

* Revised text. First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 20, Jan-Feb 2023

Luminous Epiphany

In places where the Solemnity of the Epiphany has been moved from 6 January to the Sunday falling between 2 and 8 January (both days inclusive), the readings are quite different from those that celebrate it as originally set.

Three parishes in the archdiocese of Goa celebrate the feast on the traditional day: the church of Reis Magos (The Magi), in Verem, Tiswadi; the chapel of Our Lady of Remédios (Cures) in Cuelim, Mormugão; and the church of Our Lady of Bethlehem, in Chandor, Salcete; where little boys play the Wise Men who followed a wondrous star to Bethlehem and paid homage to the Infant King.

The Epiphany (from the Greek ‘manifestation’) is an ancient feast that predates the celebration of Christmas on 25 December. It was central to Christian life because, although Jesus was born unsung, His manifestation to the Magi illuminated the mystery of Christmas.

The early Church combined the visitation of the Magi with the Nativity, the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan, and the Wedding at Cana, all of which pointed to Jesus as the Son of God. Only centuries later, at the Council of Tours in 567, the Church set Christmas day on 25 December, the Epiphany on 6 January, and named the twelve days between the two feasts as the Christmastide, with the latter solemnity marking the grand finale. The remaining feasts are spread out.

The day’s readings highlight an incomparably sublime event in the history of humankind: the manifestation of Jesus Christ. In the First Reading (Is 60: 1-6), while the prophet Isaiah looks at battered Jerusalem, he envisions it as the quintessential city that will be the Bride of the Lord. The city would manifest its glory, and the peoples of the world would flock to it with gifts, the same as the Magi would bring to the Babe of Bethlehem centuries later. Most importantly, by the end of times, 'all nations shall fall prostrate before you, O Lord,' as the Psalm says.

While the Gospel (Mt 2: 1-12) echoes Isaiah’s prophecy, it also quotes the chief priests and scribes as saying to king Herod that it was indeed written by the prophet (Micah 5: 1-2; 2 Sam 5: 2): 'And you, O Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who will govern my people Israel.'

That reference is significant, for Jesus would give up on the fortress Jerusalem and choose to be born in humble Bethlehem. The temple authorities were well aware of the coming of the Messiah, yet rejected Him.

Herod’s wily ways should be noted: he was all sweetness and bade the Magi to let him know where the Babe lay. Almost in the same breath, he ordered the killing of infants under the age of two. This is a great lesson for us who are naïve vis-à-vis the world. Although the world enjoys the benefits of Christian civilisation, it is bent on paganising the Mystical Body of Christ.

What about us Christians? Are we alert and zealous to stand up and speak up? Are we imbued with the Good News and desist from entertaining fake news? Church leaders ought to see through the devious ways of the secular, and often anti-Christian, political establishment, and refrain from partying with the impostors.

We Christians must emulate the Magi of yore and reject the world's Herods. Those noble pilgrims from the Orient, astrologers and/or philosophers conversant with Hebraic messianic beliefs, were the first Gentiles to adore Jesus; they accepted Him while the authorities cunningly rejected Him, a pathetic drama that is still unfolding in our times. They offered Him gold, in acknowledgement of the royalty of Jesus; frankincense, as a reference to His divinity; and myrrh (not mentioned by Isaiah), pointing to Jesus's suffering humanity.

St Paul in the Second Reading (Eph 3: 2-3, 5-6) states that the Gentiles are indeed 'fellow heirs, members of the same body, and partakers of the promise in Christ Jesus through the Gospel.' This is in stark contrast to the narrow and exclusive Jewish idea of Salvation. The Chosen Race had clearly failed God, so the Church is now the chosen race, royal priesthood, and holy nation. It makes you and me privileged bearers and proclaimers of His luminous message. Our task is to put the lamp on a stand, such that it gives light to all in the house! Instaurare omnia in Christo.

Banner: http://www.catholicstpeter.com/Epiphany/slides/adoration__of__the_magi-_fra_angelico.html

Under Two Holy Names

The New Year will be brought in with much fanfare the world over. The faithful will drive enthusiastically to church in their best outfits to pray for a worthy year ahead. Although it is the beginning of a civil year, we ought to honour it because Time belongs to God.

There is also a Christian facet to it. It is the Octave of Christmas and the first day of the Gregorian calendar as introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, replacing the Julian calendar whose algorithm had miscalculated the date of Easter.

Although the Gregorian calendar is now used in most parts of the world, some churches not affiliated with Rome still follow the Julian calendar. Ukraine is an example. A few years ago, in a bid to distance itself from the Russian Orthodox Church, Zelenksky’s country fell in line with the Church in the West and began celebrating Christmas on 25 December, instead of 6 January.

The first day of the civil year is also dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary in celebration of her unique privilege and title as Mother of God. Accordingly, the readings dwell on the Mother of Jesus and on the Holy Name of Jesus.[1] The Feast highlights Mary's role in the economy of Salvation and helps us place our problems and concerns under her mantle.

The Catholic Church also celebrates the World Day of Peace[2] on the first day of the first month of the year.

In today's First Reading (Num 6: 22-27) one of the five books (Pentateuch) dictated by God to Moses. Called so because it begins by listing the numbers of a census of the Hebrew people, the Book represents a march of God’s people across the desert wilderness between Egypt and Canaan. During this march, the participants gathered experiences that eventually impacted their future. God asked Moses to request Aaron, a fluent speaker, to address the Pharaoh.

Aaron, along with Moses, delivered God's message to Pharaoh: 'Let my people go, so they hold a festival for me in the wilderness'. When Pharaoh refused, demanding to know who the Lord was, Aaron performed miracles (turning his staff into a snake) to show God's power, but Pharaoh remained stubborn, increasing the Israelites' burdens.

The blessing is a general priestly blessing for the wellbeing of Israel. It is often seen as being fulfilled in the Birth of Jesus. The mystery of the Incarnation was a fulfilment of a long wait; it was a manifestation of God’s benevolence and love for humankind, His supreme creation. His Son liberated us from the old law and from sin; we have also secured His blessings, the privilege to be called God’s children (rather than creatures) being the highest one for Christians.

Of course, none of this would be possible without the willing collaboration of the Blessed Virgin Mary. She is thus, very naturally, the Mother of God and Mother of the Church, which is the Body of Christ on earth.

This is why St Paul in the Second Reading (Gal 4: 4-7) says: 'God sent forth His Son born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons.' His words highlight the human side of the Son of God, that He became man to first save the Chosen People, that He was formed by the religion of his ancestors (to us, the Old Testament), and that in time He perfected the law, whereby all men and women of goodwill would be saved.

Finally, in the Gospel (Lk 2: 16-21), the poor shepherds were the first to receive the Good News of Salvation. They met Mary and Joseph, with the Divine Babe lying in a manger. They soon understood the magnificent Hymn of the Angels, Gloria in excelsis Deo et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis, and became the first proclaimers of the Word made Flesh. They were adopted as children of God.

The fact that, at the end of the Octave, Jesus was circumcised and given His Holy Name, as preannounced by the Angel Gabriel to Mary, justifies the celebration of His Holy Name together with Mary’s title as Mother of God. It also explains why 1 January was observed as the Feast of the Circumcision of Jesus, with a Marian orientation predating it, since the 13th century. However, this feast day was cancelled by Pope John XXIII’s General Roman Calendar of 1960 and simply called the Octave of the Nativity.

Like Mary, we too need to treasure all these things, ponder them in our hearts, and be ever more faithful to Holy Scripture and Tradition. The Blessed Virgin, who had a unique understanding of Jesus's divinity and mission from the beginning, understood the full import of her Son’s words after the Resurrection and Pentecost.

We too ought to bide our time and put His Holy Name upon our world, pray for God’s blessing, and discern our vocation. Above all, by God’s grace, we ought to eschew sin, cease to be slaves of the world, and happily be sons and heirs. The affirmation of their Christian past and inheritance by European and American leaders signals a new grace that is entering our hedonistic world.

Banner: https://daylesford.org/the-solemnity-of-mary/

---

[1] The feast of the Maternity of the Blessed Virgin Mary was first granted to the dioceses of Portugal and Brazil and Algeria in 1751 on the petition of King José I of Portugal. By 1914, the feast was established in Portugal for celebration on 11 October and was extended to the entire Catholic Church by Pope Pius XI in 1931. The 1969 revision of the liturgical year changed it to 1 January.

[2] Pope Paul VI established it in 1967, inspired by Pope John XXIII’s Encyclical Pacem in Terris (1963) and with reference to his own Populorum Progressio (1967).

The Three Christmas Masses

December 25, 2022Mass Readings

Did you know of the three Christmas Masses – Midnight; Dawn; Morning – each with its own liturgy?

The Midnight Mass is also called ‘the Angel's Mass’; the second, ‘the Shepherd's Mass’; and the third, ‘King's Mass’.

Although all readings are on the theme of hope, light, and salvation, each of the three Masses has its own focus and all of them are worth reflecting upon.

The First Reading is always from the Book of Isaiah, who is the Prophet par excellence of the Messiah and the Good News. The Second Reading of the first two Masses comprise passages from St Paul’s Letter to Titus whereas the Morning Mass is taken from the Letter to the Hebrews. The Gospel of the first two Masses is from St Luke, while the daytime Mass reads from St John.

The Lectionary carries a note: 'For pastoral reasons, one or other of the three Masses may be used at any hour.'

MIDNIGHT MASS

Why a Mass at midnight? It is traditionally believed that Jesus was born at midnight. The physical darkness is a reminder of the spiritual darkness we are steeped in, a darkness that only Christ the Light of the World can dispel.

The First Reading (Is 9: 2-4, 6-7) states: 'The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light.' The prophecy is specific to Israel, whose king, Ahaz, had entered into alliances with kings instead of with the King of Kings. Isaiah announced to the hapless nation that the royal line would produce a descendant that would save them. Ahaz’s son Ezekiah was indeed a righteous king, but the adjectives describing him – 'Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace' – are infinitely more apt for Jesus Christ the Messiah, a descendant of the Royal House of David.

The Gospel account (Lk 2: 1-14) is about the humble birth of Our Lord, proof enough that His government would be of the spiritual realm. That 'there was no place for them in the inn' tells us of how the rich and mighty would reject Him, as they still do. It is no wonder that the poor shepherds were the first to be invited to visit the Divine Babe in Bethlehem.

After the Fall, there was a chasm between God and man. The Son of God came to overcome that barrier, yet we vacillate when it comes to things divine. Nowadays, when in the name of secularism, the world is steeped in irreligion and passions, let us heed St Paul’s advice to Titus (2: 11-14): '… live sober, upright and godly lives in this world, awaiting our blessed hope, the appearing of the glory of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ.'

In this dark world, then, Christmas comes with a message of light and hope for humankind.

DAWN MASS

The Mass at dawn commemorates the shepherds’ early and eager visit to adore the Lord in the manger. As natural light increases at dawn, those who believe in the Lord are blessed with His gift of light.

In the First Reading (Is 62: 11-12), Isaiah announces the good news of salvation to the daughter of Zion, that is, Jerusalem, or the Jewish people. As the luminous Psalm says, 'This day a new light will shine upon the earth: the Lord is born to us.' This light will shine on the just, and joy will belong to the upright of heart.

The Gospel (Lk 2: 15-20) tells us that the lowly – represented here by the shepherds, who were considered the scum of the earth – are the upright of heart: they see with eyes of faith, and they glorify and praise God. Like little children, it is the lowly who are apt to inherit the kingdom of God.

Yet, we are never worthy. As St Paul says to Titus (3: 4-7): 'When the goodness and loving kindness of God our Saviour appeared, He saved us, not because of deeds done by us in righteousness, but in virtue of his own mercy.' Our baptism, then, is the dawn of a new life of the spirit.

DAY MASS

The third and final Christmas Mass is celebrated in broad daylight, symbolising the promised Son of God Who has been revealed to the world. The Gospel reading is a standing invitation to all nations to worship the new-born King of Kings, hence the name ‘King's Mass’.

The First Reading (Is 52: 7-10) announces the Good News to Israel, and eventually, to 'all the nations; and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of the world.' How happy we should consider ourselves to be included in that number, thanks to the Apostles who visited our subcontinent way back in the first century (Kerala, Tamil Nadu) and later, other proclaimers of the Word, from the 16th century onwards (Goa and surrounding areas).

The Gospel (Jn 1: 1-18) strikes a somber note, that is, nevertheless, thought-provoking: 'The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world, He was in the world, and the world was made through Him, yet the world knew him not.'

How true that is of our world two millennia after the Birth of Jesus. We know Him not, and those who are privileged to know, care not! 'He came to his own home, and His own received Him not.' Jesus came to save Israel, and they rejected Him; He wants us to announce the Good News to the world, and what do we do?

How can we despise God Who has stretched out His hand to humankind?

The Second Reading (Heb 1: 1-6) emphasizes how 'in many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets; but in these last days He has spoken to us by a Son… He reflects the glory of God and bears the very stamp of his nature, upholding the universe by his Word of power.' Let us acknowledge Him duly and gratefully.

RESOLUTION

This Christmas let us reflect on the power and glory of God and how we are privileged to inherit His light on earth and everlasting life in Heaven. Let us rise above matter and embrace the spirit; let us look beyond the physical and gaze at the supernatural; let us put the pettiness of the world behind us and live like angels on high.

Thanks to the Holy Catholic Church, the ineffable mystery of Christmas stays with us through the year.

Awaiting that Wondrous Birth

December 18, 2022Mass Readings

"Behold, a young woman shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel."

We find those reassuring words in the First Reading (Is 7: 10-14). Isaiah said these things to king Ahaz, a young and evil king of Judah (731 BC to 715 BC) responsible for introducing idol worship and sacrilege against the temple of the Lord (2 Kings 16; 2 Chron 28). The Prophet wanted to win Ahaz back to the Lord by announcing the coming of a son named Ezekiah, who would save Israel. However, Ahaz despaired of God’s help and, putting his trust in kingly alliances, caused the kingdom’s decline and destruction.

Ahaz’s son Ezekiah became one of Judah’s most blessed kings. He reversed his father’s ungodly policies and restored the kingdom. He is seen as an initial fulfilment of the coming of the Messiah, Jesus. Isaiah’s words prefigured Jesus Christ, marking the beginning of messianism.

Can there be a clearer sign that Jesus was the One referred to in those words of the Prophet Isaiah? Some versions even translate ‘young woman’ as ‘virgin’. Who other than Jesus can claim virgin birth? What woman other than Mary ever gave birth as a virgin? Was it not clear that this was the Messiah that Israel had long been awaiting?

However, how many Ahazes in our midst and, sadly so, within the Church itself, have facilitated the entry of the “smoke of Satan” through a crack, as a Pope pointed out in the 1960s!

For our part, we have to “let the Lord enter! He is the king of glory,” the Psalm sings. St Paul in the Second Reading (Rom 1: 1-7) says that we are “called to belong to Jesus Christ.” This is an unparalleled privilege and supreme honour, yet how reluctantly we wear the badge! In some countries, atheism reigns; in others, indifferentism (the belief that God is indifferent to religious differences) rules the roost. Soon, such attitudes led to the renouncing of religious symbols in Catholic institutions in the name of "political correctness". It is another way of saying "God is dead".

Even in this blessed season of Advent, we find ourselves so engrossed in worldly things that we forego the birth of our Savior! It is disastrous that at Christmas, held with pomp and splendour, Christ is only a pretext for a mundane celebration. Should not the Scripture readings of this liturgical season and the Gospel (Mt 1: 18-24) of today, which dwells on the wondrous Birth of Our Lord, have moved our hearts?

In the context of Jesus’ birth, Mary had already been betrothed to Joseph when she received the divine call to be the Mother of Jesus. In those days, betrothal meant that the pair were husband and wife in all legal and religious aspects, except for actual cohabitation. So, even before they came together, Mary was with child through God’s design.

Thus, Jesus’ birth occurred in accordance with the Isaian prophecy. Yet, it was not without a trace of suspicion; and if we fast-forward to our times, some may be tempted to irreverently think of Mary as an unwed mother. However, it was clearly not so. God, in His infinite wisdom, had provided for Jesus to be born before the couple had come together, to make it clear that He was the “child of the Holy Spirit.” The virgin birth claim would have failed if Jesus had been born after the couple’s cohabitation.

No doubt, Joseph himself had reservations about Mary, who was with child; he even wanted to “quietly send her away.” Eventually, he believed the angel’s words: “Do not fear to take Mary your wife, for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Spirit; she will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus.” This was so unlike King Ahaz, Jesus' ancestor from the House of David, who became a victim of his own scepticism.

Thanks to Joseph the Silent Saint and Mary, who conceived without Original Sin, the world is blessed to have the Son of God become man to save us. For sure, the earth never saw anything more wondrous than the birth of Our Lord and Saviour.

Therefore, as we enter the last leg of our Advent journey, let us focus on our internal rather than external joy of anticipation. Let us, like people with clean hands and a pure heart, who desire not worthless things, await the divine event (cf. Ps. 23: 4), and let us wholeheartedly collaborate with God in His plans of salvation.

Joy beyond compare

December 11, 2022Mass Readings

If celebrating the halfway mark helps boost our spirits, then Gaudete Sunday does just that. Therefore, let us rejoice not only because Christmas is near but also because we have persevered in preparing for the Lord’s coming.

This Sunday draws its name from the Latin Missal’s introit, which reads: “Gaudete in Domino semper,” meaning “Rejoice in the Lord always.” Besides the pink or rose of the candle and of the priestly vestments symbolising joy, the readings, imbued with a supernatural joy, help us bide our time to contemplate the Babe of Bethlehem.

However, can we really rejoice with the enveloping world of war, disease, corruption, climate change, suffering, and unrest? Will it be possible to rejoice only in Messianic times?

In the First Reading (35: 1-6a, 10), Isaiah speaks of the time when nature will rejoice and sing with strength at the coming of the Lord of Creation to save those who had longed for Him and suffered for the sake of His Holy Name.

On the other hand, we can experience joy even though we live in this valley of tears. It is not a superficial joy brought in with festoons, but a supernatural joy that comes with faith. This joy is not a mere sensation but an act of the will—not dependent on what we feel but on what we consciously wish to feel. Truly, Christian joy is guided by our conviction that God moves and controls all history; it is not contingent on the ups and downs of daily life. By His Incarnation, we know that He is there for us and saves us: easily a cause for rejoicing, isn’t it?

In the Second Reading (Jam 5: 7-10), the Apostle[1] addresses Christians of Jewish origin. It is more of a moral teaching than a doctrinal teaching. He preaches patience, akin to that of a farmer awaiting “the precious fruit of the earth,” or a woman expecting a baby. His wise counsel is to “establish your hearts”; to “not grumble against one another”; and to “take the prophets who spoke in the name of the Lord” as role models. Simple yet effective advice. If we conduct ourselves in keeping with our faith and cultivate prudence and resignation, we will soon be on the highroad to holy joy.

Of joy, we have a harbinger in St. John the Baptist, one of the many prophets who spoke in the name of the Lord. In the Gospel (Mt 11: 2-11), Jesus says that John is “more than a prophet. This is he of whom it is written, ‘Behold, I send my messenger before Thy face, who shall prepare Thy way before Thee.’" Yet, the Forerunner of Christ, wanting to be doublesure, demands to know if Jesus is indeed the Messiah that they were waiting for. His humble ministry did not match that of the fiery, conquering Messiah expected by many.

For his part, the Messiah defines his scope of action and directs John’s gaze to how He (Jesus) fulfilled the Isaian prophecy. He had given sight to the blind and let the lame walk; He had cleansed the lepers, cured the deaf, and raised the dead. The poor in spirit acknowledged those wonders; others, finding no place for the Lord, went on from smugness to spiritual blindness and hard-heartedness.

Where do we stand? Do we realise that Jesus is the Messiah as announced by Isaiah and John? Are we poor in spirit? Do we acknowledge our spiritual need for God, like the poor shepherds did as they kept watch over their flocks by night? It is no wonder that they were chosen to be the first to hear the Good News and received it with joy.

Owing to the shepherds’ proverbial joy, the third candle of Advent is called the Shepherd’s Candle. As we light it today, may we receive the grace to be increasingly hopeful and better prepared to meet the Lord. Our joy will be beyond compare.

---

[1] “Brother [cousin] of the Lord” (Gal 1: 19), a man of great reputation but barely mentioned in the Gospel. He began to believe in Jesus only after the Resurrection and a few years after Pentecost was a leader responsible for Christian communities having a majority of Jews in Palestine, Syria and Cilicia (present-day Turkey) (cf. Acts 15: 13-29) Of all the apostles, he was the most attached to Jewish traditions – the extreme opposite of St Paul.

Panjim Church to me

In reply to a quick question from Dolcy D'Cruz of Herald, Panjim, last night... Thank you, Dolcy!

The city church has been part and parcel of my life for as long as I can remember. It is an architectural gem, perhaps best remembered for its iconic zigzag stairway.

However, my relationship with my parish church was on another plane. On Sundays, my family and I were regulars at the Mass held in Portuguese. It is also there that we attended Easter and Christmas services.

Come December, we awaited the Feast of the Patroness with great anticipation. It provided an excellent spiritual preparation for Christmas, for the angelic music of the Salves at twilight heralded the celestial choirs singing "Gloria in Excelsis Deo" a fortnight later. The church was thus my spiritual powerhouse. I still feel a strong pull even though I no longer live in the city centre.

On the other hand, I feel sorry to see the church helplessly serve as a backdrop for cultural events and photoshoots. There is scant respect shown to the sacred nature of the church complex. You find tourists dressed inappropriately, lingering on the stairway or ambling into the church premises. Who is going to stop this menace?