Steadfast in Christ

When the Greek emperors ruling over Palestine wished to impose their gods on Israel, monotheistic Israel vehemently rejected their overtures. The First Reading’s (2 Macc 7: 1-2, 9-14) description of the bid to convert seven brothers (now the Saints Maccabees) and their mother (a foreshadowing of our Blessed Mother) [1] to idolatry is pregnant with meaning. One of the siblings says in no uncertain terms that they are “ready to die rather than transgress the laws of our fathers.” If the earthly king kills them, the King of the Universe will raise them up to an “everlasting renewal of life.” They regard sufferings as nothing because they regard God as their everything; and they do so with the hope of their resurrection to life!

How many of us do readily sacrifice vain human bonds and put God first in our life? On the contrary, we often take God for granted while eager to satisfy fellow humans, especially if there are material benefits at stake. We readily bend over backwards for fear of displeasing or antagonising friends and relatives, and glibly say ‘God will understand’. Such opportunism is most displeasing to the Lord for, taking Him for granted could eventually lead to denying Him, Jesus Christ, the God of Life and Resurrection.

On the other hand, believing in the living God involves a wholehearted acceptance of the revealed message. The Gospel (Lk 20: 27-38) underlines that “He is not God of the dead, but of the living; for all live to Him.” Even this may remain as words, words, mere words, if we do not open our minds and hearts to Him. In the world today, instead of subjecting ourselves to God and His teaching, alas, how many bend before human authority, misleading though their teachings may be; and how casually they do so – as though God does not exist!

While Maccabees speaks of the apparent riddle of the seven brothers, the Sadducees mentioned in the Gospel present a teaser. A woman marries seven brothers in succession and is childless: whose wife will she be in Heaven? It is to be noted that, as against the Scribes and the Pharisees, the Sadducees (who belonged to the higher echelons of the Jewish priesthood) did not believe in the resurrection; hence their question. But then, Jesus takes the opportunity to educate them on the resurrection and eternal life: they are both for real, yet it is not a material reality like the one lived on earth; the resurrected will be akin to angels!

Resurrection and Eternal Life may well be among the most difficult realities for the human mind to accept. In our positivist age, many wish to be known as men and women of science rather than of faith. In fact, there is no antagonism between religion and science, but there are many who wish to drive a wedge between the two. To every doubting Thomas, therefore, St Paul’s prayer in 2 Thess 2: 16 – 3: 5 is: “May the Lord direct your hearts to the love of God and to the steadfastness of Christ.”

[1] Although unnamed in 2 Maccabees, the mother is known variously as Hannah, Miriam, Solomonia, and Shmouni in the Catholic Church.

Banner: The Holy Seven Maccabees, their mother Solomonia, and their teacher Eleazar (Russian veil icon, 1525)

Lux in Domino!

October 30, 2022Save our Faith

The Pastoral Bulletin of our archdiocese is once again in the spotlight. This time around, using Cardinal Newman’s words ‘Lead, kindly Light’ for its title, the editorial (Vol. LX, No. 20, 16-31 October 2022) encourages Catholics to ponder on Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. Now, light is a universal symbol, possibly one of the most powerful across religions and cultures, so we might shortly be invited to ponder on what light means to the Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, and why not, to communists, anarchists and satanists as well! Such efforts at political correctness are sure to propel Renewal into the global spotlight.

The spotlight per se is not the issue; readers are afraid of the bulletin's current editorial policy blocking the Lord’s light. The main purpose of a pastoral publication is to be a beacon to the sheep, guiding them to the right pasture. On the plea of enlightening the sheep, the editor has steered them to other pastures instead. Is this the mandate the sacerdotal class has received from Our Lord Jesus Christ, who said, “I am the Light of the World. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness but will have the light of life.” (Jn 8: 12)?

The impugned editorial speaks for itself. In a brief introductory paragraph, the editor reports his Divine Master as only one among equals. The remainder of the two-page leading article is divided fourfold: “Celebrations surrounding Divali”, expatiating on the five days of the festival; “Symbolism of Divali”, unravelling four key figures; “Christian Attitude towards Divali”, which carries the editor’s self-invitation to share in the joy and celebration of the Hindu community; and, finally, “Christian Understanding of Light”, in which he barely touches on the issue of Christ’s light at baptism. Earlier, he put the dipa and the nur Allah on par with the Paschal Candle… An absolute melange!

What ought to be our attitude towards the non-Christian festival of lights? According to the editor, “Christians could visit their friends and neighbours during Divali. They need not participate in the religious and faith dimension of the festival but they can surely participate in the social and cultural dimension of the festival.” It isn’t a ‘must not’ (negative obligation) but a ‘need not’ (absence of obligation); so, one is not required to do the thing, especially if one does not want to, but can do it if one wants to. One is completely free to act at one’s own discretion, no holds barred.

Beneath that poorly disguised disclaimer lurks the editor’s tacit approval. Note how over half of the editorial is dedicated to the “religious and faith dimension of the festival” – precisely the thing that Christians “need not participate in”! The lay faithful for their part have traditionally engaged in “the social and cultural dimension”, incurring no censure, by cordially greeting neighbours and/or friends. As a friend of mine says, it is a pity that “good sense observed by the lay faithful since times immemorial is shockingly being violated now by some priests and nuns with all their theological preparation.”

The freethinking editor goes on to suggest as follows: “The Christian could move further from the mere ritual of the festival to a better knowledge and understanding of the festival. The Christian could discover the richness of the symbolism, which crosses the boundaries of religion.” For God’s sake, what boundary crossing is that? A euphemism for a vague, universalist mysticism supposedly superior to all religions? It suggests that pastors have tasted it, so as to feel stimulated to ‘shepherd’ the flock…, er, away from the reality of our religion and of the Living God! What a travesty of our Faith! Is there nothing sacred anymore?

The final step in the editor’s flawed catechesis is here: “Organize inter-religious prayer meetings”, using Diwali “as a forum and an occasion to express solidarity with our Hindu brothers and sisters. Hence, inspired [sic] and dialogue on symbolisms of the festival, people from different faiths could get themselves together for a better bonding and understanding as humans and citizens.” Leaving the broad use of ‘faith’ for another day, what you have there is a mirage!

The said instruction sends the sheep not just to unknown pastures; sadly, it sends them out to the deep sea without a compass! On the one hand, Nostra Aetete, which encourages the study of other religions, states that “dialogue and collaboration with the followers of other religions” has to be “carried out with prudence and love and in witness to the Christian faith and life”. On the other, who can deny that our very own pasture is still relatively unknown to our sheep – largely through the fault of the same priestly class? And how impressive is our “witness to the Christian faith and life”? “I am the Way, the Truth and the Life”: are they words, words, mere words?

Apropos Nostra Aetete, which motivated the establishment of the Secretariat for Non-Christians, later called ‘Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue’, may I point out that it was recently renamed ‘Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue’, and not Dicastery for Culture and Education, as the editorial states! And there is more. If one “need not participate in the religious and faith dimension of the festival”, why “organize inter-religious prayer meetings”? And, pray tell, what “people from different faiths could get themselves together for a better bonding and understanding as humans and citizens”? For better bonding as humans, there’s nothing better than plain old good sense; and as citizens, we go by the Constitution. So, something terribly wrong there; or maybe, as Lord Polonius says in Hamlet, ‘Though this be madness, yet there is method in it.”

We have detected the first part; but what about the ‘method’? Execution of new-fangled notions by clerics enjoys at least silent consent, if not total approval, from the ecclesiastical authorities; but for fear of opening a Pandora’s box, the laity have been kept in the dark, not to say left in the lurch. It is indeed the intricate art of the slow reveal, although it is already quite evident that a new religion or a new church is on the horizon. The rest of us, however, are confident that “nothing is covered up that will not be uncovered, and nothing secret that will not become known. Therefore, whatever you have said in the dark will be heard in the light, and what you have whispered behind closed doors will be proclaimed from the housetops.” (Lk 12: 2-3)

Is it not abundantly clear that Renewal is sponsoring an eclectic mix of religions? This Diwali, WhatsApp images declaring Jesus as the Light of the World – and yet with a ‘Happy Diwali’ greeting merrily tagged on – made the rounds. The editor of Renewal may not be directly responsible for this faux pas, but we can’t help but wonder if this kind of ‘renewal’ will soon be the order of the day! The incongruity of the message apart, does it not amount to misappropriating concepts from other religions and diluting our own? We can’t feast on such a ‘fruit salad of religions’, can we?

But then, that is how Syncretism works. A cross between two things is neither one thing nor the other; it can even cause strange occurrences like “photosynthesis of human living” [sic], to which the editorial makes a passing reference. Be that as it may, no photosynthesis can ever take place using earthen lamps! We always need the Light of the World.

Repentant and Ready

As the curtain gradually comes down on the liturgical year, the readings focus on the Last Things: Heaven, Hell, Death and Judgement. Unfortunately, there is a strange conspiracy of silence over those four realities associated with the end of the world. They are seldom mentioned in homilies, sermonettes or sermons, but it is in the fitness of things to exercise our minds and hearts in this regard. They form an integral part of our Lord’s command “Go into all the world and preach the Good News to everyone” (Mk 16:15), the Good News being that of our eternal salvation.

The First Reading (Wis 11: 22; 12: 2) expresses King Solomon’s faith and trust in God’s omnipotence. The son and successor of David bows in deep humility before the One for whom the world is but a speck. His creation continues to exist because He wills it. He lauds His mercy and love. By His infinite love, He corrects “little by little those who trespass”; He gives us a long rope but also warns us. He wants us to be happy through our participation in the divine life. Not even philosophers had come upon such a marvellous doctrine before.

If we pause to review how well we accept God’s gentle interventions, which come in least expected ways, we will see that He is kind and compassionate, slow to anger and abounding in love. His ways are so different from ours that we sometimes distrust them. His message may not be music to the ears but is the truth nonetheless. We ought to thank the Lord and praise His Holy Name, which, alas, the rich and famous sometimes fail to do.

Zacchaeus in the Gospel (Lk 19: 1-10) was an exception to that rule. A rich tax collector, he yearned for a divine encounter. He felt rewarded when Jesus visited his home. There were murmurs, because as per the Jewish law communicating with sinners meant impurity. To them, it was a scandal; to Zacchaeus it meant a change of heart. The people did not realise that the Son of Man had come “to seek and to save the lost”. Indeed, what a difference it made in Zacchaeus’ life! His act of renouncing material goods was a sign that he was ready to receive spiritual goods.

Don’t we have a standing invitation to redirect our gaze to Heaven? It pays a hundredfold to seek the Lord and His Kingdom. The peace and joy that fills us is invaluable; the treasure that awaits us in Heaven, incomparable. Hence, we should live dignified lives, worthy of the Lord’s call.

In that regard, St Paul’s message (2 Thess 1: 11; 2: 2) in the Second Reading today is ever relevant. Like us, the Thessalonians too lived in times of persecution and tribulation, which put their Christian vocation to the test. They believed the end of the world was imminent. The Apostle of the Gentiles moderates their euphoria and gives them hope of the time when Jesus comes again in His glory: those who once faced trouble for His sake will now find rest and consolation; they will be glorified, whereas their persecutors will go to their eternal damnation.

When we are assailed by temptations and fears, we must not be shaken. There are both true and false prophets in our midst; we must not rush or feel excited but be calm and discerning. We must work to let His Kingdom come here on earth. We must repent for our sins and be ready to receive our reward. For one thing is sure: God is in control of every situation and will not allow His Bride, the Church, to face defeat. Similarly, we have the reassuring words of Our Lady, Mother of Jesus and of the Church: “In the end, my Immaculate Heart will triumph.”

Prayer of the spiritually oppressed

Today’s readings especially bring hope to the oppressed. They speak of God’s ways as different from those of man. Those who trust in the Lord can rest assured that they will be protected on earth and rewarded in Heaven.

In the First Reading (Sir 35: 12-14, 16-18), the reassuring message is that God is fair, though not unduly partial toward the weak. He lends a listening ear to those who call on Him, responds to our prayers, and does justice to the righteous. This is a far cry from human justice, which is vitiated by relativistic thinking and prompted by friendships and self-interest.

When our miserable world speaks of justice or injustice, it is usually on the material plane. However, material oppression, be it physical or economic, is not only one that we ought to be concerned about. Man does not live by bread alone but by every word that proceeds from God’s mouth.

The oppression of the spirit is the worst form of oppression. The spiritually oppressed are those who find themselves unable to realise, or are prevented from realising, their raison d’être in this world: the realisation of God’s kingdom. Ironically, some of those who, by virtue of their holy office, are obliged to let God’s kingdom come, simply take God for granted.

Others assume a spiritual superiority vis-à-vis the man in the street. They may be so hard-hearted that they fail to empathise with the poor sinner who has had a change of heart. Hence, our Lord’s words of indignation are as follows: ‘Woe to you, teachers of the law, and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You shut the kingdom of heaven from men’s faces. You yourselves do not enter, nor will you let those who are trying to enter.' (Mt 13)

In the Gospel (Lk 18: 9-14), the Parable of the Pharisee assumes that he has a hotline with God. He despises the tax collector, who is at the receiving end of society.

Can the Pharisee’s mere observance of the letter of the law allow him to take the moral high ground? Perhaps the major difference with their counterparts in our times is that they take the moral high ground even when they blatantly break the traditional and written law. Like Satan in Paradise Lost, they say: ‘Evil, be thou my good.’

Thankfully, in St Paul (2 Tim 4: 6-8, 16-18), we have an advocate for the spiritually oppressed. He announces that when he was on the point of being sacrificed, the Lord rescued him from the lion’s mouth, from every evil, and gave him the strength to proclaim the Word fully—that all Gentiles may hear it!

Woe to those who seek to silence rather than proclaim the Word of God. This is the worst kind of oppression that the spirit can endure. For example, freedom of religion—to practise and preach—is a fundamental right, which is in peril in our country and in many other parts of the world.

Of course, those who have given their heart and soul to Jesus Christ will endure just anything with serenity and joy, and when their time is up, they will gladly say: ‘I have fought the good fight; I have finished the race; I have kept the faith. Henceforth, there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness.’

This moral certainty will be the crowning glory of the prayer of the spiritually oppressed.

Persevering in Prayer

Alexander Pope, one of Britain’s most famous Catholic poets, wrote, ‘Hope springs eternal in the human breast.’ This is now an oft-repeated quote, but just how many of us realise that prayer sustains hope? Today’s readings dwell on the need to pray at all times—a theme at the heart of Christian living. Saints and spiritual masters down the ages have discussed it at length.

The manner in which the First Reading (Ex 17: 8-13) describes the struggle between the Amalekites[i] and the Israelites may lead some to believe that prayer is a magical formula or that God has his favourites whom He grants all requests. Notably, while Moses directed Joshua, his successor, to engage Amalek in battle, he himself kept watch and prayed incessantly for the success of his nation’s efforts.

God does not save us unless we partake of our own salvation. Therefore, we must do what we can before expecting God and our fellow humans to help us. Moses held supernatural trust and confidence in the Lord. Aaron, his elder brother and first High Priest of Israel, and Hur, an Israelite leader, possibly of the tribe of Judah, who served as a companion to Moses and Aaron, helped him. Their collective effort teaches us that when we have done our best, God does the rest!

In the Gospel story of the Unjust Judge (Lk 18: 1-8), Jesus impresses upon his disciples the need to always pray without becoming weary. The parable bears a close resemblance to that of the Friend at Midnight (Lk 5: 8). Elsewhere, Jesus says, ‘Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and you shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.’ (Lk 11: 9). Yet, we should not take God for granted. We must ensure that our prayer is worthy and pleasing to God; we must pray in humility, faith, and perseverance.

That’s not all. A key aspect of prayer is to talk less and listen more; not try to bend God’s will to ours but our will to His. An indulgent parent may grant their child any request; but not God, who will concede only what is in our interest and in keeping with His omniscience. Hence, St. Augustine suggests that we pray as if everything depended on God and work as if everything depended on us. His wise counsel can bring us peace of heart.

In a godless world, many may doubt the efficacy of prayer, but they are the poorer for it. It is not a good idea to challenge God, who has us in His hand. Our pride prevents us from acknowledging God’s presence and works. Thankfully, those who are open to His loving kindness will stoutly say with Tennyson: ‘More things are wrought by prayer than this world dreams of’.

It is absurd to deny or forget that we are beneficiaries of God’s loving kindness. However, we are quick to say that corrupt men and women enjoy a great time on earth and demand that God show His justice forthwith! He will, in His time. Meanwhile, we must acknowledge the miracles He has wrought in our lives. God never forgets the labour of love done to honour Him. ‘He will see to it that justice is done for them speedily.’

In fact, the Evangelist makes a cutting retort to ungrateful humans: ‘When the Son of Man comes, will He find faith on earth?’ These words are an eye-opener to the present state of the world, whose words and actions often affront God’s Holy Name. Woe to us if our love for God has grown cold! In the Second Reading (2 Tim 3: 14–4: 2), St. Paul exhorts us to ‘remain faithful to what you have learned and believed, because you know from whom you learned it’.

The Sacred Scriptures and Tradition are our rock, guiding us to salvation through faith in Christ Jesus. We ought not to twist them and cosy up with the New World Order; rather, we are to use the Scriptures ‘for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training in righteousness’. The Apostle to the Gentiles urges us to ‘proclaim the Word; be persistent whether it is convenient or inconvenient; convince, reprimand, and encourage through all patience and teaching.” We are called to serve the Lord—to be ‘joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer” (Rom 12: 12).

Banner: Five saints depicted in the Eglise du Sablon, Brussels

[i] Amalekites were the descendants of Amalek, the grandson of Esau who was the twin brother of Jacob (later called Israel). The Amalekites became a nomadic tribe and the enduring enemy of the Israelites. This is remembered by the Jews to this day, but historically its occurrence is debatable. Hence, today, the battle is just symbolic of evil and perpetual hostility.

Laity and Clergy in Goa: Moods and Expectations (3/3)

October 10, 2022Save our Faith

As we bring the present set of sentiments to a conclusion, we reiterate that we wish to see our faith practised in accordance with Church doctrine. People are thirsty for the Living Bread and the Living Water; they feel repulsed when they get a snake or poison instead. As Jesus said, ‘And which of you, if he asks his father bread, will he give him a stone? or a fish, will he for a fish give him a serpent?’

It goes without saying that this blogpost, like all the previous ones, is about OUR Faith – and not others’ beliefs. We are not questioning the constitutional freedom of others to follow their own beliefs. And they too, like us, may not wish to see syncretic practices disfiguring or diluting both sides. In short, ‘good fences make good neighbours!’

Let’s, therefore, not mix spirits and create a strange concoction. The subject at hand is of supreme importance and never too much to dwell on. It’s a matter that impacts the foundations of our Faith and, consequently, Eternal Life, and so never too much to ponder on.

Which brings us to our request to the Authorities: feel the pulse of the laity. Or, as the Pontiff has said, listen to your people!

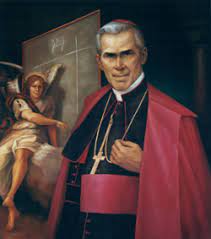

Much earlier, the Venerable Fulton Sheen did not hesitate to state something that, today, could appear “arrogant”: ‘Who is going to save our Church? Not our bishops, not our priests and religious. It is up to you, the people. You have the minds, the eyes, and the ears to save the Church. Your mission is to see that your priests act like priests, your bishops act like bishops, and your religious act like religious.’

It is in this spirit of reverent and filial appeal to His Eminence Cardinal Ferrão, that we say: Listen to our voice. Vox populi, Vox Dei!

Virgin Most Faithful, pray us! St Thomas the Apostle, pray for us! St Francis Xavier, pray for us! St Joseph Vaz, pray for us! Holy Souls of our ancestors converted to the Catholic Faith, pray for us! May God save our Faith!

And here we end our first catalogue of sentiments. Read on!

**** […] beautifully narrated but shocking. Are you sure it’s one of our priests or someone impersonating him to mar the reputation of the Catholic religion! […] If priests do not obey the Commandments, then what teaching would they give their flock? Where is our religion heading? [..] I sincerely hope and pray that the matter will be clarified by the ecclesiastical authorities in the archdiocese and by the CBCI. If not, I can just visualize the effect this will have on our youth… Prayer is our only weapon. – SP – My comment: The name of the priest and the proceedings are on record.

**** Concordo plenamente e reforço o que expressou no seu post.

**** […] What the priest is doing here seems to be of Syncretism (?) not of interfaith dialogue.

**** We have visited and greeted our Hindu friends for Ganesh Chaturthi even during the Portuguese days when we were children, much before we heard such big words as 'inter-religious dialogue'. But, of course, we did not fold our hands and pray in front of the idol of Ganesh and pose for photographs. If our dear priests (and nuns) could observe just this simple rule of good sense, they would avoid spreading error and creating controversy.

**** Who is this priest and where is this place? Can one worship two Gods? What’s this nonsense! What more is left? Such a shameful act! And that’s what makes God so angry. This priest should be suspended, as priests are in the form of Jesus Christ Himself, especially when they serve Mass at the altar.

**** It looks like a policy that ‘if you can't fight them, be with them. Don’t antagonize them’. Not joining them by changing to their faith is to live peacefully. – My reply: If we respect our identity, others will also respect us. Those who are not happy should leave the Church and join the other side. We can’t keep our legs in both the boats.

**** This is very sad and dangerous on their part. First it was priests singing bhajans and now this! I had in fact stopped going […] to people’s houses long ago as some of them expected [me] to bow before the idol.

**** How far some of our people go!

**** [‘Does our Sensus Fidei need Renewal?’] is relevant to caution our laity and priests. Well researched. – PRIEST

**** Já que aos padres não interessa proteger e disseminar, tem de ser os leigos a defender a Igreja Católica…. É pena que a nova geração dos padres não tenha queda académica no seu ADN. Acho que não temos pessoas para os orientar.

**** […] Agree with what you have stated. I too have interacted personally with some priests and expressed my strong concern in this regard. We have to be vigilant and alert and let the priest know of our deep concern and anxiety in such matters. They need to feel the pulse of the laity. I get the impression that instead of listening and acting appropriately they have…. [truncated message]

**** Excellent [ref. to ‘Does our Sensus Fidei need Renewal?’]. Remarkable, such extensively theologically researched… I too got enlightened with many of the Church documents. – PRIEST

**** Sadly, this issue is slowly distancing the Church leadership from the lay faithful and evils of pride and ego may only give Satan a broad entry.

**** […] I’m hoping our clergymen read this and get our Church back on track.

**** […] Read your response to Renovação’s tirade. […] If priests and their sheep really worshipped the idol it is preposterous. I got the forward about this event from a hard core ‘Believer’ who thus picked up one more stone against the Catholic Church. Your response to Renovação is sincere, highly well informed and extremely well written. You have spoken for the community. […]

Banner: https://www.historytoday.com/history-matters/strange-afterlife-pontius-pilate

Laity and Clergy in Goa: Moods and Expectations (2/3)

In continuation of yesterday’s post, here are the final lines of the PRIEST’s letter, saying that the Catholic priests have been “an object of acerbic criticism by probably some vested interests who have found the social media very handy for the dissemination of their bilious anger against Catholic priests and the Church in general.”

‘Vested interests’? A ruse to divert people’s attention from pressing issues! The enemies of the Church are not outside but inside. It is not only the ‘smoke of Satan’ that has entered the Church; it is Satan himself who is lurking in our midst, and many simply don’t wish to notice his presence.

Why blame the social media? Another convenient ruse. Doesn’t the Archdiocese have a Centre called the Diocesan Centre for Social Communications Media? Don’t priests individually use social media to disseminate news and views? And how much of it is the ‘Good News’? A case in point are the views expressed by the clergymen on this forum: often ambiguous, sometimes contradictory, rarely the full truth.

‘Bilious anger’? Nay, Righteous Anger! We are with the Priests as long as they are with God! Let’s speak the truth, and nothing but the truth. Facts are facts; against them, there can be no arguments. ‘Let your speech be yes, yes: no, no: and that which is over and above these, is of evil.’ (Mt 5: 37). That’s the people wish. Vox populi.

Some more comments below show the mood and expectations of the Catholic laity and clergy in Goa:

*** I have sent it to some senior priests. Can something be done or the priest corrected? … I sent it to some top clergy. Let’s pray that they take this seriously. I sent it to a Nirmala sister too. They didn’t answer me. But Sister was upset. She summoned me to Nirmala’s to speak to her… I told her the last post came from Canada and sent by a very good friend who was also an ex-student of Nirmala Institute of Education… And we are concerned about what’s happening… I told her that some lay people and priests too are upset with what’s going on. Inculturation is one thing, but this is crazy. To which she just kept quiet.

*** […] There is a thin line between respecting everyone’s faith and praying to other deities. Total breach of our First Commandment. Really sad.

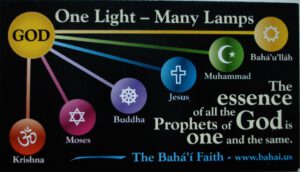

*** We had a conference for catechists recently at Joseph Vaz Centre, Old Goa, to explain the Pastoral Letter 2022 of our Bishop. The above image [‘One Light – Many Lamps’] was used in the presentation slide by the priest… Through the catechists, they are corrupting our children… Since they started such exercises, has the religious harmony increased or is it more vitiated now than earlier? […]

*** […] Wonder what we could do to educate our priests. I am game for anything.

*** What is happening! So sad. Hopefully there is a […] clarification from Church authorities.

*** Claro, como diz, uma coisa é o diálogo e bom convívio inter-religioso, outro é sincretismo… Ainda para mais, dada a idiossincrasia goesa.

*** […] There is no punishment by our Church. Christian politicians worship idols and break coconuts in front of them. Archbishop has not commented or excommunicated any of them. So, Catholics in general are not cautioned against the consequences. One priest's excommunication without much publicity would send a strong message down clergy and lay persons... It's ridiculous to see things happening around us ... Nowadays, I don't know if you have come across the streets in Panjim... There are these so-called fellowship groups, Born-again Christians going about talking about the Bible, convincing you about things in the Bible... They know the Bible so well that a fool can get mesmerized... I would say that's sheep stealing...

*** I agree with you 100%. I’ve said the same thing time and time again. I particularly condemn the blatant idol worship indulged in by many of our so-called ‘Catholic’ politicians…. But a priest doing the same thing is taking it to another level altogether… I'll be posting your article liberally, both individually and in various groups.

*** This interfaith dialogue has crossed boundaries.... Our priests (some of them) bend over backwards to please […] those who matter. We don't see them coming to our homes at Christmas time, and bowing in front of the crib, for example. If Goa has gone to the dogs, it's the Church to blame. […] I feel quite disgusted with this […] attitude of some of our religious starting with those at Archbishop House.

*** […] I’m aghast that a Catholic priest could do what he’s purportedly doing here. I hope there’s an explanation somewhere.

*** Very true. It violates the very First Commandment.

*** I came across your social media post ‘Elephantine Blunder’. […] The priests did not bow before the idol but prayed to God along with the family without invoking Ganesh. – My comment: That’s instant absolution! Which ‘god’ would he pray to other than the idol itself?

*** It may be for optics, which is also a blunder.

*** It is absolutely wrong to pray before other gods, I agree. However, social visits to people of other faiths during their festivals should be encouraged. It is also unfortunate that inter-religious dialogue has been limited only to organising prayer meets, with no room for inter-religious dialogue of life issues. We have so much in common to work for to establish justice and peace in our society. – PRIEST – My reply: Interaction on the social plane is fine but we can't compromise on the tenets of the faith. Such syncretic practices are an absolute no-no. – PRIEST: I agree.

Banner: https://lucascranach.org/en/DE_SKD_GG1941

Jesus, our Light and our Life

Today’s readings are about giving thanks, glory, and praise to the Lord our God for the wonders He has wrought in our lives… They are about remembering him with gratitude and never taking Him for granted… They are about doing our bounden duty and awaiting the crown of glory when the race is done.

The first and third readings talk about healing. In the First Reading (2 Kings 5:14-17), the Syrian general Naaman goes into the river Jordan, as recommended by prophet Elisha, and comes out clean, his flesh restored like that of a little child. He returns with a present to thank the man of God, who does not accept it, for he was not there to serve himself but the Lord. Extremely thankful, Naaman wishes to carry earth with which to build an altar for the Lord in whom he now believes, in his land of origin.

In the Gospel (Lk 17:11-19), only one of the ten lepers who were cleansed returned to thank Our Lord. An instance of kam’ zalem, voiz melo (once cured, one forgets the physician), a classic case of human ingratitude. The Master Physician notes that the lone grateful man whose faith had cured him is indeed a foreigner – a man from Samaria, a district that was anathema to Israel.

The two stories above are not about physical healing alone; they are about being liberated from sin, yet failing to proclaim the Good News to the world. How many of us who stop everything to ask God for healing and success also stop to thank God on receiving them?

The Anglican-turned-Catholic writer G. K. Chesterton, in his Autobiography, stresses ‘the idea of taking things with gratitude, and not taking things for granted.’ But alas, gratitude seems to be one of those rare commodities in our jet age. It is as if we expect everything as a right, and nothing as a favour. In our self-centredness, no gesture of kindness from another ever touches our hearts. Sometimes, a ‘thank you’ is a mere formality, and when it comes to God, hardly a necessity.

St Paul (2 Tim 2: 8-13) clinches it. He places before us the everlasting model that is Jesus Christ, our Lord. Our Lord is faithful even to the unfaithful – because He can’t be any different. What a noble lesson for humanity! The Apostle to the Gentiles, who, a little earlier in the letter to Timothy, had spoken of the good fight, the race, and about keeping the faith, now uses a fragment of a hymn from his area of evangelisation to convey the same message.

The point is: why do we sometimes deny Him? Why are we faithless and unfaithful? Is it mere weakness, or is it malice? Sometimes we unknowingly get caught up in the web of the evil one. Let us break free. Let us wake up and think. Let us rise and speak. The Word of God is not fettered. Have faith, Jesus is the Light of the World; those who follow Him will have the light of life.

Laity and Clergy in Goa: Moods and Expectations (Part 1/3)

Given below are some of the WhatsApp messages received from members of the laity and the clergy in response to our posts, ‘Elephantine Blunder’ https://bit.ly/3ClZHaP and ‘Does our Sensus Fidei need Renewal?’ https://bit.ly/3SM9zSr, dwelling on an issue that has wounded the core of our Christian being: relativism, syncretism, idolatry… by some of the very people who are supposed to – and claim to – respect and protect it. St Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologica says that violation of the First Commandment is ‘the most grievous sin’.

The present catalogue of sentiments does not include general messages of appreciation and support received. Writers’ names do not appear; in the case of Priest writers, the same is specifically mentioned. Some messages have been slightly edited, for clarity; and those straying into other areas have been left out altogether.

Meanwhile, it is reported that His Eminence Cardinal Ferrão has expressed consternation at the turn of events and has justified the laity’s angry outbursts. In his address to the Deanery heads of the Archdiocese, he allegedly condemned idolatry, appealing to his priests to exercise caution when on social visits to people of other faiths. On insisting that Christians use the word ‘Lord’ to refer exclusively to Jesus Christ, His Eminence purportedly said that he does not visualise a repetition of such ugly incidents in the future. Unfortunately, there is still no official confirmation of the sentiments expressed by our Cardinal.

It may be said that in face of such a heinous scandal, an oral warning to the Deans or to the entire Goan clergy is not enough. Verba volant; scripta manent! Spoken words fly away; written words remain. Hence, only a Circular issued to that effect by His Eminence condemning the scandal and explaining the doctrine of the Church regarding the sin of idol worship can set the record straight and bring the issue to a logical and just conclusion, not least because the Archdiocese’s official organ – Renovação /Renewal/ Novsornni – in a recent issue (16-30 September 2022) sang a different tune. This is our request.

To great evils, greater remedies! Here is a cancer that is not amenable to chamomile tea! The laity expect clear-cut directives; a stern rebuke to the perpetrators; and acts of reparation – all of which the Church habitually does in grave matters – indeed, grave as it, as the messages below bear out:

- ‘You did well, indeed, in just two words: “Elephantine Blunder”! Now that this topic has come up, let me say that on this particular Sunday [12/9/22] our priest explained at length all the mighty attributes of the 'lord': the fine eyes, trunk, the arms and the articles they are holding, the big paunch, the carrier-vehicle, the first transplantation surgery, and the broken tusk – and went on to say that all these attributes are already Catholic and we should have no qualms about it […] Lord, have mercy on us! …’

- ‘I totally agree with you. Thanks for raising your voice against paganisation in the Church.’

- ‘This is one of the reasons why other sects such as New Life, many self-proclaimed ministries, attack the Church, stating that she's impure. The Church is not impure, she is holy; but just because of some fallback/practices done by some of the religious ministry – such as this idolatry – she takes a hit. It is so sad. God bless us.’ – [Fwd]

- ‘[…] I have stopped looking at what they are doing and read and teach Jesus’ Gospel Word. Please follow and try to obey Jesus New Testament Word. If you don't mind, I will send you some Word from Jesus Gospel […] I have spoken to the [clergy] and find that they do not have the Holy Spirit to understand Jesus’ Gospel, so let us forgive them and work to understand Jesus’s Word for our own Salvation.’ – My reply: We can’t overlook what they are doing! They are supposed to show the way; they hold souls in their hands… Forgiveness is one side; Justice is the other. And this is what we want… God also wants us to be alert and stop being naïve. They are pulling the rug from under our feet... Counter-reply: The Devil also uses people in authority to build his own church.

- ‘Just because the position is facing the idol in no way does it mean he is praying to the idol. I would like to bring to your attention that Jesus narrated the three parables to the Pharisees who considered themselves better than the tax collectors and other sinners… Pictures deceive. I know very well that he has caused no scandal. Again, I say the prodigal son's parable was addressed to the pharisees who made life difficult for others.’ – PRIEST [Fwd] – My comment: The priest is clearly in prarthana position. And it is reported that he led the parish youth to pray and sing (hymns from Gaianancho Jhelo).

- ‘This is abominable. Who is this priest?’

- ‘[Your article] has been a big blow to false inculturation and to the pan-ecumenical revolution.’

- ‘To me, it looks as if Ghar Whapsi has begun in Goa.’

- ‘[...] a total abomination in the sight of our Living God. This is so utterly disgraceful... Bowing to [...] idols by a Catholic clergyman. Shame on him and the system he follows...’

- ‘Oh, my goodness! Where was this? That’s so alarming. This is actually against our First Commandment, is it not?’

- ‘[…] And since these are teachers/Shepherds who lead the faithful in idol worship they will be severely judged as Jesus has already stated. God! This is so scandalous and we thought only [...] were idol worshippers...’

- ‘[...] next time do not share items against the Church... By sharing we become part of those who are against us...’ – PRIEST [Fwd] – My comment: What a shallow remark! Well, this is not against the Church but against a scandal performed by a Priest, tarnishing the image of a true Pastor… Were the Popes who condemned Luther and the Modernists enemies of the Church?

- ‘It’s good that you called this out. About time that someone did it… Maybe you should send it to Dr Taylor Marshall!’

- ‘So, this is one of our own priests!... Really!!... And is our Archdiocese not aware? I wasn’t!... That amounts to testing Almighty God Himself… Shudder at the thought… We have no Moses anymore… It cannot be an accident that the very First Commandment covers this issue… it means that this is topmost on the list of God’s mind.’

- ‘You are so right to express your justified anger against this idolatry despite God's express Command. God must have mercy on us, before His wrath consumes us!...’

Finally, I transcribe part of a comment from a priest holding a high position in the Church:

- ‘[…] I agree with you a hundred per cent that the photograph that you have published shows a priest whose “prayer posture absolutely begs an explanation.” He is seen praying with his body turned towards the idol. As ambiguous and compromising as his prayer posture may be, would you like to think, even for a second, that he is saying something like, “O Lord Ganesha, please hear our prayer”? At least I would not.’ – PRIEST – My reply: ‘Thank you, […]! I don't wish to guess what the priest is saying, much less put words in his mouth. He will have to give an account to God. But a pic is worth a thousand words, hence the criticism on social media. It has its reason for being.’ – PRIEST: Agreed.

(To be continued tomorrow)

Banner: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/aaron-brother-moses-worshipped-golden-calf

Goencheo Mhonn'neo - II | Adágios Goeses - II

October 6, 2022Sayings and Proverbs,Goan Literature

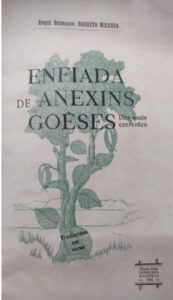

Neste número, em continuação do anterior (Revista da Casa de Goa, 2022, II Série, No. 17, pp. 35-38), divulgamos mais adágios seleccionados e traduzidos, do valioso repositório bilíngue (concani-português), Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, da autoria de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda.

Neste número, em continuação do anterior (Revista da Casa de Goa, 2022, II Série, No. 17, pp. 35-38), divulgamos mais adágios seleccionados e traduzidos, do valioso repositório bilíngue (concani-português), Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, da autoria de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda.

Entretanto, no texto que segue, note-se seis vocábulos portugueses concanizados: Entrudo; Páscoa; festa; cruz; experimentar; letrado. É que o português e o concani mutuamente se influenciaram.

| Tradução literal | Tradução livre | |

| Moddvol’achém moddém bâ’yr kaddlyâ bagôr, kãy colo’na. | Só quando vai-se enterrar

um mainato, se avalia se era ou não do próprio, a roupa com que em vida se vestia. |

Há oportunidades

que mostram realidades.

|

| Roddtyâ dadlyak ani hanstê baylek patiyevum na ye. | Do homem a chorar

e da mulher que ri, é bom desconfiar. |

|

| Anddir assá cheddó, sodunk bountá sogló vaddó. | Tendo o filho à ilharga, vagueia

a buscá-lo por toda a aldeia.

|

Quem não anda com tento e atenção,

não nota até no que está junto à mão. |

| Sat’tê fuddém xahaneponn kityak upcara na. | Ante o poder ou pressão,

não prevalece a razão. |

|

| Mas khailolém Intrudak, dênk ayló Pascanchyá-festak. | Comera carne

Na ocasião de Carnaval E teve arrôto No dia da Festa Pascal.

|

Atribuir, sem razão,

o resultado ou efeito a uma causa de ficção. Variante A coisa passou outr’ora, e vem tratar dela agora. |

| Dilolém naká, sanddlolém zay. | Não quer quando é of’recido,

E quer, quando está perdido. |

Quando tem, não aproveita,

rejeita a utilidade, e quando há falta, sente a sua necessidade. |

| Anthurun pormaném pãyem sôddche. | Conforme a cama

que possuir estenda os pés para dormir. |

Para governar-se sempre bem,

Tem que viver-se co’ o que tem. |

| Moddlolyá kursák kon mann di na. | A cruz, que se vê quebrada

por ninguém é respeitada.

|

A quem deixou de ser rico ou potente,

festas e adulações não faz a gente. |

| Goroz zaly, voiz meló. | Conseguido o objectivo

morreu o facultativo.

|

Obtido o favor

já não mais se lembram do seu benfeitor. |

| Experimentar zalyá sivay, letrad zay na. | Sem experiência ter

letrado não chega ser.

|

É sempre p’la observação

Ou prática, que das coisas Se tem a melhor noção. |

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 18, Setembro-Outubro de 2022, pp. 33-34)