Goencheo Mhonn'neo - I | Adágios Goeses - I

July 13, 2022Sayings and Proverbs,Goan Literature

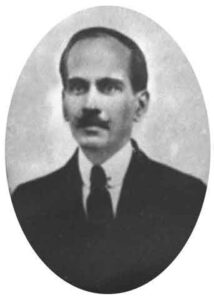

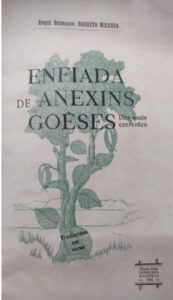

É possível que a literatura oriental seja ‘o mais precioso repositório de adágios e provérbios, como o é de fábulas e de contos populares,’ afirma João de Figueiredo[i] no prefácio à Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda.

Filho do grande literato Jacinto Caetano Barreto Miranda, de Margão, além de trabalhar como chefe da impressão da Imprensa Nacional, em Nova Goa (Pangim), colaborou na imprensa local com prosa e verso. De entre a sua obra poética, encontram-se Coisas sabidas (1923), Disparates em verso (s. d.), e ainda um e outro trabalho inédito.[ii]

Na Enfiada, vêm à luz 200 ditos regionais, que nas palavras de Barreto Miranda são ‘flores do folclore de Goa’. Recolheu-os, em primeira mão, na conversação da gente, traduzindo a maioria deles em duas versões, literal e livre, ambas transcritas mais adiante. Não se trata, pois, de provérbios, máximas ou sentenças, o que seria de sabor clássico, mas, simplesmente, de adágios, ditados, ou rifões, de sabor popular.

Dir-se-ia que esse trabalho prima pelo seu valor sociológico e poético. Uns anos antes, monsenhor Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado publicara, pioneiramente, em Coimbra, Florilégio de provérbios concanis (1922), contendo 2177 provérbios. Mas havia, sem dúvida, espaço para mais gente na seara.[iii] Barreto Miranda publicou anexins, dos mais correntes, no Heraldo, diário panginense, porém, numa altura em que poucos teriam dado conta do serviço que estava a prestar à terra.

Ainda por cima, traduziu os adágios, primorosamente, em verso, pondo-os assim em pé de igualdade com a sabedoria comum dos povos e a literatura universal.

Ainda por cima, traduziu os adágios, primorosamente, em verso, pondo-os assim em pé de igualdade com a sabedoria comum dos povos e a literatura universal.

Ora, quanto à ortografia e pronunciação dos vocábulos concanis, transcrevemos a seguir, como informação de utilidade, e não menos de curiosidade, as palavras de Barreto Miranda:

‘A escrita do concani – cuja ortografia em caracteres romanos, por não estar ainda bem definida – foi feita, para facilitar o leitor, possivelmente, conforme a fonologia popular em voga.

‘Relativamente à pronunciação: por não haver no alfabeto romano fonemas com que se possam exprimir precisamente certas palavras concanis, servimos da geminação de letras – letras cacuminais – as quais têm de ser fortemente articuladas com a ponta da língua, para dar o som aproximadamente natural da pronúncia concani. E para fácil enunciação, devem as palavras pronunciar-se em sílabas separadas. Para exemplo: melyá – kaddlyar – dounddolyá – vaurtolyak – devem ler-se assim: me-l-y-á – kadd-ly-ar – do-un-ddo-ly-á – va-ur-to-ly-ak.’[iv]

Não subscrevo de todo o sistema ortográfico seguido pelo estimado autor da Enfiada, limitando-me a observar que, quase um século após essa sua advertência, e apesar de, no enretanto, ter havido várias tentativas no sentido de uniformizar a ortografia e pronunciação da língua concani (sendo uma delas segundo o sistema Jonesiano, apresentada por monsenhor Dalgado), a situação continua no mesmo pé. Mas isso pouco retira o valor à Enfiada de Barreto Miranda.

Tradução literal | Tradução livre |

|

Melyá bagór sorg melâ na. |

Não se chega a ver o céu sem morrer. Não se alcança qualquer bem ou ventura sem passar por trabalhos e amargura. |

Tondd aslyar vatt assá. |

Quem boca tiver, tem via que quer. Chega para onde quiser, no país desconhecido, quem sua língua souber. |

Boreak guelyar fattir yetá. |

Por ir alguém fazer o bem, mais das vezes o mal lhe advém. |

Tenkdênn momv kaddlyar, tonddant poddâ na. |

Nunca a boca saboreia quando se quer apanhar, com cambo, o mel da colmeia. É melhor por si fazer, p’ra, o que se deseja, obter. |

Dounddo’lyá fatrár pãyon dovorçó nay. |

Não deixar nunca o pé assente sobre uma pedra movediça, (por se deslocar facilmente). É sempre acto de imprudência meter-se em negócio incerto ou coisas de contingência. |

Dongrá-vôylim zaddâm Dev ximptá. |

As plantas dos oiteiros (desprezadas p’la humanidade) são por Deus regadas. Aos que não têm lar, nem pão, sempre a Providência toma sob a sua protecção. |

Dholé add, sounsar padd. |

Fora da vista (e cuidado) o mundo fica arruinado. Quando o dono está ausente, as coisas, que lhe pertencem, são roubadas livremente. |

Muclyém zot vetá taxem, fattlém zot vetá. |

A junta de bois de traseira segue conforme anda a primeira. Do que o de diante faz, segue o exemplo o de traz. |

Dek’lem moddém, ailém roddném. |

O ensejo de encarar o cadáver, fez chorar. As ocasiões provocam acções. |

Borém corchém ani fattir gueuchém. |

Fazer o bem e afinal receber p’lo dorso o mal. |

[i] Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes, traduzidos em verso, de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), p. VI.

[ii] Cf. “A Evolução do Jornalismo na Índia Portuguesa”, de António Maria da Cunha (in Índia Portuguesa, volume 2, Nova Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1923); A Literatura Indo-Portuguesa, de Vimala Devi e Manuel de Seabra (Lisboa: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1971); Dicionário de Literatura Goesa, volume 1, de Aleixo Manuel da Costa (Macau: Instituto Cultural de Macau e Fundação Oriente, s.d.); Dicionário de Goanidade, de Domingos José Soares Rebelo (Alcobaça, 2012). Embora o Dicionário de Literatura Goesa se refira a um inédito intitulado “Frutos sem sabor”, disse-me Jacinto Barreto Miranda, sobrinho do Poeta, que não consta nenhum manuscrito desse nome no espólio do tio.

[iii] Thomas Stephens (c.1549-1619), missionário jesuíta inglês residente em Goa, publicara alguns adágios goeses na sua Arte da Lingoa Canarim, os quais foram traduzidos livremente pelo orientalista J. H. da Cunha Rivara (1809-1879), na segunda edição dessa gramática por ele publicada, em 1857. Isso para não falar de conjuntos posteriores, traduzidos em português e em inglês, estes por V. P. Chavan (Konkani Proverbs, 1900); S. S. Talmaki (Konkani Proverbs and Idioms, 1932), António Pereira, jesuíta goês, (Konknni Oparichem Bhanddar, 1985), e, mais recentemente, por Edward de Lima (Konknni Oparincho Kox: A Book of Konkani Proverbs, 2017); ou ainda os publicados em outros lugares de expressão concani, tal como nos estados indianos de Karnataka e Kerala.

[iv] Enfiada, pp. X-XI.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 17, Julho-Agosto 2022)

Being a Good Samaritan

Who can deny that the world would be a better place if we followed God’s commands to the hilt? No doubt, sincere people take to them like fish to water; they don’t find them difficult to follow, ignore them, play up or spurn them. The natural moral law is etched in our minds, and we know it by heart. As the First Reading (Deut. 30: 10-14) says, ‘The Word is very near you: it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it.’ In the modern lingo, we are hardwired to love God’s law and must beware of worldly-wise, pirated software designed to infect the system!

God is not crazy or eccentric; His law is not ‘out-there’, unusual and unconventional. He has had covenants with us, but alas, we have failed to honour them! In days of old, God spoke directly to His people or to a prophet. But then, being invisible had its flip side: God began to seem distant, so He sent His Only Son to be born of a Virgin. Jesus walked the earth, spoke the language of the land, worked miracles to everyone’s amazement, and died for our sins in an unprecedented outpouring of love. The essence of his parting words was that we love God and neighbour.

But isn’t that easier said than done? In the Gospel (Lk 10: 25-37), a Jewish scripture scholar, after admitting that one can inherit eternal life only by loving God (Deut 6: 5) and neighbour as oneself (Lev 19: 18), demands to know who is our ‘neighbour’. His question makes sense for, to the Jews, only a member of their religion or race was a ‘neighbour’. The scholar probably wished to hear a novel definition that would navigate through issues like religion and ethnicity (Jews/Gentiles) gender and class (clean/unclean). Instead, Jesus responded with a parable that unimaginably expanded the scope of the term; and He topped it up with a question that dispelled all doubts!

In that touching and famous Parable of the Good Samaritan – which St Luke alone reports – he who attended to that half-dead man, with compassion, was from a region that the Jews looked down upon because of their mixed ethnicity and worship outside Jerusalem. Nonetheless, Jesus introduces us to an individual Samaritan whose behaviour is a far cry from that of the Jewish priest and the Levite (temple assistant from the Hebrew tribe of Levi). Were these two too busy to stop and help, or were they merely playing it safe, for touching a dead man would prevent them from carrying out their temple duties?! Or maybe not, for Jesus talks about their going down from Jerusalem (temple) to Jericho (home), and not the other way around.

While Jesus leaves the backstory a complete mystery, we can rest assured that God had moved the Samaritan to set an example to generations to come!

Which brings us to the Second Reading (Col 1: 15-20) in which St Paul emphasises that Jesus alone can inspire and help us humans to love and serve. The Apostle to the Gentiles portrays Christ as the mediator between Creation and Redemption: He who was present at the time of the creation of the world will also be the One through whom the world will be redeemed.

Shouldn’t He, then, be the focus of our life? Our life makes sense only through Him. Note the multiple repetitions of the word ‘all’ in the passage: the writer wishes to emphasise the fact that there is nothing outside Him who is the Way, the Truth and the Life. He is the be-all and end-all of our existence. This reality can never be emphasised enough, lest we begin to sacrifice the truth of the Gospel to the distorted values of the contemporary world.

The values of the contemporary world are centred on money, power and influence. They hold us in bondage; they prevent us from reaching out to others in love, as Jesus did. Subservience to the material world is a despicable form of bondage from which only God’s laws can liberate us. Hence, Jesus alone is deserving of our trust and confidence; He alone is our model for doing things through love. So, it is not good businessmen but Good Samaritans who are God’s instruments of hope – "Fools for Christ" (1 Cor 4: 10), in this mad, mad world!

However, being a Good Samaritan does not mean being naïve; it does not demand suspension of our critical faculties. In the near-Godless world we live in, steeped in malice and misunderstanding, Good Samaritans must indeed act with discernment. Be it at home or at work; in a school or a hospital, in the street or on the battlefield – reaching out to our neighbour is of the essence. One sure way of achieving this by warding off pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath, and sloth. When we evict those seven trespassers, God comes into our minds and hearts, moving us to be Good Samaritans in a way that is most pleasing to Him.

Mudança... unforgettable vacation in Goa! (2)

This is the second and final part of the testimonies translated from my podcast Renascença Goa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=24yo5MFthrg and published in Revista da Casa de Goa.

We first have GABRIEL DE FIGUEIREDO, who lives in Melbourne, Australia. He recalls the days that he spent his holidays at Colva beach and in his native village of Loutulim, both in the taluka of Salcete.

We first have GABRIEL DE FIGUEIREDO, who lives in Melbourne, Australia. He recalls the days that he spent his holidays at Colva beach and in his native village of Loutulim, both in the taluka of Salcete.

What I understand by mudança: for us kids, mudança was a change of environment - it was going from the city of Panjim, where we lived during school days, to the village of Loutulim and Colvá to spend the holidays and refresh the “soul”. Until about 1964, our Aunt Margarida used to arrange a little house in Colvá for us to spend the month of April, to enjoy the fresh sea air and take a bath, or swim in the sea waves. Our uncles Sebastião (from Margão) and Francisco (from Benaulim), together with their families, used to join us to spend their April holidays there. I don't know why after 1964 we stopped going to Colvá – maybe the owner of the house had changed.

What I understand by mudança: for us kids, mudança was a change of environment - it was going from the city of Panjim, where we lived during school days, to the village of Loutulim and Colvá to spend the holidays and refresh the “soul”. Until about 1964, our Aunt Margarida used to arrange a little house in Colvá for us to spend the month of April, to enjoy the fresh sea air and take a bath, or swim in the sea waves. Our uncles Sebastião (from Margão) and Francisco (from Benaulim), together with their families, used to join us to spend their April holidays there. I don't know why after 1964 we stopped going to Colvá – maybe the owner of the house had changed.

Well, as ours was a musical family, after returning from the beach to the little house, it was time for solfeggio, singing and violin. Apparently, it was here that my father, António, started writing Mandó arrangements after his return to Goa on completion of his training in orchestra conducting at the University of Paris.

Well, as ours was a musical family, after returning from the beach to the little house, it was time for solfeggio, singing and violin. Apparently, it was here that my father, António, started writing Mandó arrangements after his return to Goa on completion of his training in orchestra conducting at the University of Paris.

When we returned to Loutulim to spend the month of May, we had access to home-grown mangoes, jackfruit, cashews, etc. Even in Colvá and also in Loutulim, as there was no electricity supply at the time, Aladdin or Petromax lamps were used at night to give enough light to read. And I read a lot of books those days, more in English than Portuguese, because my maternal grandfather had a book-case full of Reader's Digest, National Geographic, novels like The Saint (Leslie Charteris), Sherlock Holmes, etc. Around 25 May, a feast of Enthronement of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Mary used to be celebrated, along with uncles and cousins who also came to spend a few days with us.

Those were days full of happiness and games. The mudança in October was only to Loutulim, taking advantage of the mid-term vacation that coincided with the Divali festival. We used to hold a novena to Our Lady of Sorrows in the second half of October, with a Rosary sung in Latin and Konkani, on alternate days, the ‘Salve Rainha’ followed by ‘Virgem Mãe de Deus’, both sung in Portuguese.

In those days, it was customary for all uncles and cousins to come to spend holidays with us in Loutulim, until the last day of celebration. It was ten days of absolute happiness. Well, after my father passed away in November 1981, this tradition of the month of October came to disappear, unfortunately. My brother Vicente makes an effort to maintain the tradition of Enthronement, along with my sisters Teresa and Celina, inviting cousins and their families (now extending to a few generations) to sing a litany in May, when they go to Loutulim for a mudança when possible.

In those days, it was customary for all uncles and cousins to come to spend holidays with us in Loutulim, until the last day of celebration. It was ten days of absolute happiness. Well, after my father passed away in November 1981, this tradition of the month of October came to disappear, unfortunately. My brother Vicente makes an effort to maintain the tradition of Enthronement, along with my sisters Teresa and Celina, inviting cousins and their families (now extending to a few generations) to sing a litany in May, when they go to Loutulim for a mudança when possible.

Our next guest is SAADIA FURTADO, from Chinchinim. She remembers spending holidays in Fatrade beach in Varca village.

Our next guest is SAADIA FURTADO, from Chinchinim. She remembers spending holidays in Fatrade beach in Varca village.

In Goa, the word Mudança is used in a slightly different manner from its original meaning: it means mental rest accompanied by physical relocation. In general, one would go for a mudança during a weekend or when there were public holidays. People from inland areas went to the beach to enjoy the fresh air and to bathe in the sea. It was a healthy practice. One could also go for a mudança by going to a relative's or friend's house or live in a rented house in places where there are fountains and springs which have sources of medicinal properties in water, especially in the case of patients with high blood pressure!

In Goa, the word Mudança is used in a slightly different manner from its original meaning: it means mental rest accompanied by physical relocation. In general, one would go for a mudança during a weekend or when there were public holidays. People from inland areas went to the beach to enjoy the fresh air and to bathe in the sea. It was a healthy practice. One could also go for a mudança by going to a relative's or friend's house or live in a rented house in places where there are fountains and springs which have sources of medicinal properties in water, especially in the case of patients with high blood pressure!

I fondly remember our mudança to Fatrade Beach at Varca, during the months of April and May. There I spent a few days in the company of my parents and relatives. It was a mudança that helped us rejuvenate.

I fondly remember our mudança to Fatrade Beach at Varca, during the months of April and May. There I spent a few days in the company of my parents and relatives. It was a mudança that helped us rejuvenate.

Nowadays, we talk about, that is, when someone goes from one state or country to another for about a week or a fortnight. This meaning is considered different from the term mudança in Goa.

Finally, FAUSTO COLLAÇO, who lives in Margão, goes down memory lane to the holidays spent at his ancestral villages of Raia and Benaulim.

The covid-19 pandemic and its mutant waves heckle us. When talking about holidays, the only holidays we could think of at the moment is to stay at home and spend the holidays there. However, this compulsory retreat takes us back nostalgically to the holidays we used to spend during our childhood, in Goa – the Goa that was for us and the tourist, a Paradise!

When children, we enjoyed semestral holidays. They lasted for over a month each time and so, offered the right opportunity for some holidays during which we stayed over at our grandparents' place in the village! On my mother's side it was the beautiful village of Benaulim and on my father's side it was Raia.

Coming to Benaulim was for us, setting foot on a Fairyland of boundless freedom and fun! My grandparents' place was a confluence of all people - cousins, uncles and aunts, granduncles and aunts, domestic help and, beyond the walls of the house, family friends and the entire village of Benaulim – from the smallest to the greatest! The chapel in the neighbourhood, tolled its bells morning and evening, proclaiming as though, the dawn and dusk! The children whiled away their time at play and also planning out small skits and recitals which accompanied the dinner of the older people at home. They in turn, were an ocean of love and affection! My grandmother used to bring to the table savoury traditional dishes, pickles and desserts. There was always abundant seasonal fruit like mango and jackfruit.

The evenings were often spent in walks by the beach where one would always meet up with friends. We went on occasional picnics in family or in groups. The picnics were naturally regaled with singing and guitars strummed by my uncle Joaquim or other friends. At sunset, the little feet happily plodded back home where, in those bygone days, one was welcomed to the shimmer of kerosene lamps!

The evenings were often spent in walks by the beach where one would always meet up with friends. We went on occasional picnics in family or in groups. The picnics were naturally regaled with singing and guitars strummed by my uncle Joaquim or other friends. At sunset, the little feet happily plodded back home where, in those bygone days, one was welcomed to the shimmer of kerosene lamps!

The ensuing holidays were spent in Raia – my father's ancestral village. It was a particularly quiet and peaceful village. Our house stood in the remote interior, in a ward called 'Santemoll'. It was calm and far from the bustle of the city. Once there, one only heard sounds of nature: birds chirping, distant joyful shrieks of children playing, the bellow and the moo. A river flowed luxuriously a little distance away. Other familiar sounds were the honking of the door-to-door bread or fish vendors and the tinkling of the postman on his cycle. He always had a smile, was cheerful and courteously greeted us while even waggling a tad of Portuguese!

Here too, we enjoyed seasonal fruit and, towards the end of May, heralded by lightning and intimidating thunder, came the showers – initially a light drizzle which soon swelled into a heavy downpour! The gutters gurgled noisily and the fields flooded up with rainwater. The weather cooled, grasses and weeds sprouted here and there. There was a burst of green everywhere! The ploughman plunged into work toiling the fields with a pair of oxen and a wooden plough, swinging into action his strong and able arm, with a dextrousness defined by many years of experience! He transformed the field into a veil of greenery undulating in the breeze - an enchanting sight for the locals and tourists alike!

Such was the idyll of village life in Goa and of our holidays in the villages! Today, consequent to changing times, they're quite different and are on their way to even greater transformation. One hopes, however, that this idyll which was the life and the land of Goa, will never be lost altogether.

------

Acknowledgement: Many thanks to the three guests for their respective translations published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 17, July-August 2022. The third text was further edited by the respective author for this blogpost.

On the mission field

Today’s Readings grab our attention: the First, by Isaiah’s colourful imagery (Is 66: 10-14); the Second, by St Paul’s passionate testimony (Gal 6: 14-18); and, of course, the third by Jesus’s stirring voice (Lk 10: 1-12, 17-20). Close on the heels of last Sunday’s Gospel passage, which invited us to be resolute in disseminating God’s Word, Our Lord brings into sharp focus the mission of His disciples – which is our mission too!

Coincidentally, in India, 3 July is the Solemnity of St Thomas, the Apostle. The readings proper to the occasion are from Acts 10: 24-35; Heb 1: 2-3 or Pet 1: 3-9; and Jn 20: 24-29, whose last sentence from the mouth of Jesus is ‘Blessed are those who have not seen, and yet believe’. However, we are going to comment on the readings proper to the universal Church; by God’s grace, they also fit like a glove, dwelling as they do on the life of a missionary, which St Thomas was one par excellence.

A fragment of today’s Gospel reading rings in the ear of every believer: ‘The harvest is plentiful, but the labourers few.’ How many did Jesus commission? Some codices say seventy, others seventy-two: both figures are right, as they represent the pagan communities (70 in the Hebrew text, 72 in the Greek) mentioned in Genesis 10.

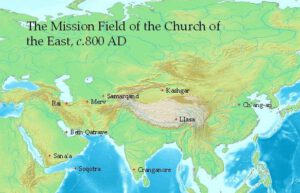

St Luke is the only Evangelist who makes a mention of this number, suggesting that Jesus would not limit Himself to the twelve tribes of Israel (denoted by the Apostles) but would reach out to all communities and nations. One of them, St Thomas, travelled to South India and died there. And as members of the Church today, it is our responsibility, until the end of the world, to evangelise like them, without fear or favour.

It is noteworthy that Jesus spoke to the seventy-two after He had spoken to the Twelve (see Lk 9). Thus, the Gospel was proclaimed first in Israel and thence to others. Jesus commanded the disciples to go ahead of Him into every town and place. That He sent them out ‘as lambs in the midst of wolves’ spoke volumes of the trials and tribulations awaiting them in a hostile world. Yet, He bid them to carry no purse, no bag, no sandals, and to salute none along the way: He expected them to trust in Him alone.

The disciples also received some practical tips from the Divine Master. They were not to waste time in elaborate greetings, so typical of Oriental cultures, but to focus on announcing the Good News without delay. The disciples were to eat, drink and accept accommodation as provided to them, for the labourer deserves his wages; but they were not to have expectations or make demands – for God would sustain them. They had to reach out to the sick – not only physically but spiritually – by giving them the hope of eternal salvation.

Jesus made an interesting distinction between what was to be the disciples’ behaviour in a household and in a town per se. Not only would their greetings differ, but their attitude as well. If an individual or his household refused the disciples, the latter’s response would be milder than when a town rejected them. In the latter case, Jesus recommended that they shake off the dust of their feet. He promised them authority over the enemy and that their names would be written in Heaven. The disciples fulfilled their mandate diligently and, no wonder, they returned with joy.

If Our Lord’s occasionally tough language does not match that goody-goody image of Him, let’s remember Jesus was not a goody-goody; He called a spade a spade, was earnest about his Father’s holy business and brooked no nonsense. Thus, the peace His disciples carried went beyond mere greetings of good health and prosperity; it was a messianic peace. And the hard-hitting words that Jesus and His disciples uttered were but messianic lamentations, for the fate that awaits detractors is one worse than Sodom’s.

If Our Lord’s occasionally tough language does not match that goody-goody image of Him, let’s remember Jesus was not a goody-goody; He called a spade a spade, was earnest about his Father’s holy business and brooked no nonsense. Thus, the peace His disciples carried went beyond mere greetings of good health and prosperity; it was a messianic peace. And the hard-hitting words that Jesus and His disciples uttered were but messianic lamentations, for the fate that awaits detractors is one worse than Sodom’s.

Jesus expects us to adopt a like posture; we are not to trivialise God. St Paul, who witnessed similar crises in the communities he tended, concludes his letter to the Galatians, by stating that salvation lies only in the Cross of Christ: ‘I do not wish to take pride in anything except in the cross of Christ Jesus our Lord,’ he said unequivocally. This is an eye-opener for us who we must learn to guard against sacrificing the truth of the Gospel to materialistic values and goals. Let us not doubt, let us not harden our hearts when we hear the Lord’s words.

We who have had the fortune of meeting our awesomely loving God must proclaim His works. The prophet Isaiah fashioned most beautiful images to give us an idea of God’s unfathomable love: it is like that of a mother for her child; of a husband for his wife; of a bridegroom for his bride. We too must acknowledge God’s omnipresence, omniscience and omnipotence. We must strive to be true disciples of Christ, the salt of the earth and light of the world. We must not hide the light under a bushel but set it upon a lampstand so that it radiates light to all in the world.

If we announce what God has done for our souls with true missionary zeal, the world will cry out with joy and sing glory to His name!

Mescla de memórias e expectativas

Editorial

Editorial

Esta edição da nossa Revista é uma mescla de memórias e expectativas. Reflectimos sobre o que fomos, somos e podemos vir a ser. Aliás, o hábito de pensar foi sempre uma marca da nossa sociedade, tanto em Goa como na diáspora. E isso se torna premente na hora que passa, por razões que, pelo menos em parte, estão elucidadas por José Maria Miranda, no artigo ‘Elections in Goa’, e por Leslie St Anne, em ‘Cry, my beloved Goa’, título que lembra o dum famoso romance sul-africano, situado no prelúdio do apartheid.

Este ano, a chuva da monção (ilustrada pela nossa capa) como que prenunciou a nomeação de monsenhor Filipe Néri António Sebastião do Rosário Ferrão, Arcebispo de Goa e Damão, para o cardinalato. A notícia caiu como maná sobre essa Arquidiocese de tradições pluricentenárias, cujo titular justamente goza do título honorífico de Patriarca das Índias Orientais, existente desde o ano de 1886, e oxalá assim continue. Na verdade, como se explica que da minúscula Goa tenha saído um número bem significativo de Cardeais? É pergunta que faz o nosso editor associado José Filipe Monteiro, tornando-se, portanto, obrigatória a leitura do seu artigo intitulado ‘Goa e os Príncipes da Igreja’.

Ainda quanto às tradições de Goa, uma delas é a Mudança. Não se trata de transição política (embora esteja a tornar-se rotineira), mas, sim, de como nos tempos que já lá vão se passava as férias, nos campos e nas praias em Goa: falam delas Gabriel de Figueiredo, Saadia Furtado e Fausto Collaço, no podcast de Renascença Goa, nosso novo parceiro editorial. É assunto agradabilíssimo, como também o é esse renovado interesse que se nota, em Goa, pela música portuguesa, nomeadamente, o Fado. Este é cantado a todo vapor por jovens como Shrusti Prabhudesai que, de facto, pouco ou nada sabem da mudança de regime político que se operou na sua terra há sessenta e um anos.

É aconselhável, porém, que as novas gerações saibam toda a verdade histórica. É sinal de sociedade democrata e vibrante. Nesse contexto, é oportuna a apresentação de um opúsculo centenário, intitulado ‘Os [H]Indus e a República Portuguesa’, da autoria do Juiz António de Noronha, que foi Presidente da Relação de Goa. Foi um livro muito controverso, e, ora traduzido por Ave Cleto Afonso, continua a sê-lo. Entretanto, o recenseador José Filipe Monteiro diz de sua justiça: a verdade, sem exageros.

Se um livro pode marcar uma geração, muito mais se dirá de um indivíduo ou grupo de pessoas. E é louvável quando se trata de gente que se esforçou no sentido de fortalecer, e nunca deixar ruir, a nossa sociedade. Nesse sentido, destacamos duas figuras, uma de antanho e outra da contemporaneidade: a de Albino Pascoal da Rocha, médico, que morreu ao serviço da Pátria, em Moçambique, pela pena de Mário Viegas; e a de Júlio Aguiar, activista social e ambiental que cedo pagou o tributo à Natureza, e ao qual Francesca Cotta presta homenagem.

De entre crónicas, temos ainda ‘The Miracle Boy’, em que António Gomes relata com saudade um acontecimento da sua infância. E em ‘On a sentimental journey’, Ralph de Sousa lança um olhar nostálgico sobre as embarcações chegadas a Goa das sete partidas do mundo. E falando ainda de mar, Júlia Serra, na sua crónica intitulada ‘Figuração do Mar na literatura e nas viagens no Oriente’, refere-se ao ‘Oriente, tradicionalmente tão desejado, apesar das dificuldades de navegação “por mares nunca dantes navegados”.’ E remata essa secção a crónica hilariante de Radharao Gracias: ‘What’s in a name?’ Tudo isso a não perder!

Ora, temos duas novidades que valem por deliciosa sobremesa: o nosso editor associado Valentino Viegas traça o perfil de ‘Ave Cleto Afonso: um fervoroso defensor de Kônkânní’, apresentando uma publicação deste (‘Kônkânní – a língua de Goa e a alma do seu povo’), que valeu como ‘brado’ no quinquagésimo quinto aniversário do Opinion Poll, o crucial escrutínio de opinião que se realizou em Goa, no ano de 1967. É uma efeméride que urge comemorar, de modo especial, na hora que passa!

Temos ainda mais uma novidade em forma de livro: Once upon a time in Goa, da autoria de Joaquim Correia, um português apaixonado pela investigação musical nas antigas colónias portuguesas, o qual ora se debruça sobre a música e dança em Goa e na diáspora. E temos ainda a companhia do Poeta Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda e a sua Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, da qual respigámos uma dezena de adágios e rifões. Duas obras que nos podem acompanhar no café da manhã, ou no serão da tarde à indo-portuguesa!

Com toda essa mescla de memórias e expectativas ficam também os nossos votos de boa leitura, nos dias de chuva ou de sol, dependendo de onde nos encontramos na diáspora!

Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 17, Julho-Agosto de 2022

Stuti and the Strings

June 29, 2022Goan Music,Interview

This is a translation of a chat I had with Fr Eufemiano Miranda, founder of Goa String Orchestra and Stuti Chorale Ensemble, on my podcast Renascença Goa. Click here for the original chat in Portuguese.

O.N. Father Miranda, to begin with, tell us something about how these two entities were born, and for what purposes!

E.M. Well, I first started the Goa String Orchestra… that was some time in 2003, when here in Goa we had a choir coming from King’s College, England. They presented a beautiful programme at the church of St Francis of Assisi… And then I thought to myself: we in Goa who always say we are the Italians of the East… we have nothing organized, be it a small orchestra, a small choir… None of that. It was worth having something.

At that time, there were some young people who had graduated in violin, viola, cello. And there were also teachers, among them Myra Shroff, who has taught almost a whole generation of students; and she would always say to me: ‘ah, can’t we have a little string orchestra?’ And I would say, ‘why not?’ So, with whatever we had, I started an orchestra.

Well, it’s not enough just to bring together the members of an orchestra; you have to have a dynamic person behind it, to give it life, to give it movement. And at that time, I started the Goa String Orchestra with Mr Nigel Dixon, who was then with the Kala Academy.

O.N. Very good. That was around 2003. And years later…?

E.M. And later on, there were people who watched our shows and enjoyed what we performed; and there were people who wanted to sing – people with good voices – and with these people I started the Stuti Choral Ensemble, in 2009. It has always been my goal to keep the tradition of classical music alive in Goa…

O.N. Father, you are the driving force behind both these entities…

E.M. Well, I like to use a simpler word: I am a coordinator. My job is to say to these musicians: ‘Come here, let’s make music’; and with their collaboration, I do my work.

O.N. Father, you are much more than that… you have an important voice in both entities, both figuratively and literally speaking, because you also sing!

E.M. Ah, yes! I sing, I enjoy, I enjoy singing. I sing tenor.

O.N. And how many members does Stuti and Goa String Orchestra consist of?

E.M. At Goa Strings, I have a few who, I would say, are regular artists… these would be about 10. Every year there are students who graduate, and I keep calling them; and I like to form a string orchestra with some 18 members or so…

O.N. So, Stuti always has Goa Strings for musical backing…!

E.M. No, no; each entity works independently, but, as you know, in Goa it is difficult to organize concerts in two modalities, choral and instrumental; and so, I prefer to call the choir and orchestra to present a programme together.

O.N. And so far, you must have done at least twenty-five programmes, both inside and outside Goa…!

E.M. That’s it! When Stuti was formed, we immediately got a call from the Bangalore School of Music for a Christmas programme. And it was going to be our first opportunity to perform in public, outside of Goa. We got good reviews in the Bangalore papers. I would say this gave us new motivation.

Well, we always work within our means. For example, at the moment, I am working with a person, a good friend of mine, Antonio Calisto Vaz, and I have asked him to direct the Stuti Choral Ensemble. But I consider it a divine grace that I have conductor Parvesh Java with me.

Fostering Goan Musical Talent

O.N. In the general plan of both Stuti and the Strings Orchestra, what role does the Goan musical repertoire play?

E.M. As I have always said, my ideal is to preserve Goan music. Evidently, we have music from the Christian community of Goa, both religious music and folk music. In my orchestra programme I always wanted to have Goan music played by the orchestra, and we had to present programmes: so, what would we present? My brother, Francisco Miranda, who is a priest and good musician, and I chose “Diptivont Sulakini”: it was so beautiful! I wrote an introduction; he wrote that for two flutes and strings, and accompanied by small Indian timpani (kansaddi), because, as you know, that is a typical Goan music. It’s a Western melody, I would say, but not entirely Western, but not an Eastern melody either, but it’s typically Goan, and one that can be perfectly performed to the Indian rhythm, let’s say. Then I could perfectly play it using the tabla and kansaddi. And we did that under the baton of Nauzer Daruwala. It was really beautiful…

O.N. Well, what adds value to your work, Father, is that you not only perform, but also take the trouble of working on arrangements and harmonies…

E.M. That’s it! We are a group, let’s say, that sings stylized music, in four voices. It is necessary to harmonize that to four voices. If an orchestra is going to play that, it needs to be harmonized for five strings, so the very fact that our group, both instrumental and choral, is a stylized, erudite group, we have to make this music, whether folk or religious, more stylized. After all, what was that music from Europe? Pablo de Sarasate, for example, wrote the Spanish dances: it’s music from Spain that he stylized. The same with Brahms who did the Hungarian dances; Dvorak wrote the Slavonic dances. My way of thinking is this: why can’t we do the same?

O.N. And how do you solve logistical problems?

E.M. I always say to my choir and orchestra members: look, we have to make music for music’s sake, art for art’s sake. Our rehearsal time is 6.30 p.m. to 8.00 p.m. I am very grateful to Kala Academy for giving us the facility to use the rehearsal room once a week…every Wednesday.

O.N. So, what plans for the near future?

E.M. I don’t have big plans. We want to continue to do the work that we are doing, that is, to value music from Goa and to have a group here that is a voice that represents Goa, and in the event of having to present a programme, we would be ready to present a small one, anywhere…

O.N. …like musical ambassadors of Goa!

E.M. We would like to be that!

Western Classical Music Scene in Goa

O.N. Father Miranda, how do you see the western classical music scene in Goa?

E.M. Well, first of all, I would say that to have a taste for Western classical music, you need to have a certain preparation, you need to have a certain musical education. In Goa, there are people who enjoy classical music. And it all depends on people, taste, education and promotion… it all depends on the family… I mean, I really like classical music, but why is that? Because when we were little – we are eight brothers and sisters – my father was very fond of classical music. It was at a time when there was nothing, nothing... when we were little children, there was only a gramophone... and then he would play, he liked to play that, and talk about that music... Well, there was music that we liked and some other that we didn’t like. But my father always instilled in us this taste for music… ‘That’s a beautiful Beethoven melody; that’s a beautiful Mozart melody’, he said… and he sang it himself. There is, therefore, the cultural climate of the family that contributes greatly to the promotion of classical music.

In the seminary, music was and still is a subject. You have to study music and pass in that subject, if not, one wouldn’t be ordained... My other brothers who went to high school at that time had a music academy there. There was choral singing there, in high school. Home and school: all this contributed to my brothers’ and my liking for classical music.

But the taste for classical music is not so widespread throughout Goa. We like to listen to it, but we don’t bother to appreciate it so much: that’s what’s lacking among us.

O.N. Father, you have been part of Kala Academy’s advisory board for a few years… What is left to be done before we seen an improvement in the level of teaching and musical culture?

E.M. Well, I would say that we need, first of all, a person with the highest musical academic training… A good musician has to know how to write the music, harmonize the music; a good musician must also know how to compose music and then he must also eventually know how to direct, and encourage others to sing and play. There are so many aspects. To do so, you have to have a degree at a higher institute of music…

Contribution of the Goa Church

O.N. Well, what is the Seminary’s contribution towards the promotion of sacred music and towards the development of the musical sense of the Goans?

E.M. Ah, I would say in my day it was western music all the way; and Gregorian music… All that was part of the curriculum. I don’t know how it is nowadays.

I had good teachers… I had a teacher called Father João Baptista Viegas: he was self-taught; he was a good musician and he himself learned to play the violin and teach music from Dominic Pereira. This was a great musical figure, a violinist from Porvorim; he was a family friend of Dominic Pereira’s. He learned from him, and he played the violin himself. It was a pleasure to see how Father João Baptista played the violin and taught the students.

Then, at Rachol Seminary, I had maestro Camilo Xavier: he had passed through Rome where he learned music and did a lot for the cause of music in Goa.

Now, the Seminary, where priests are trained in music, has contributed a lot. I would say, a musical culture was developed through the Goan clergy.

Well, the Church has always had the liturgy in mind... the priests and musical formation in function of the liturgy. Hence, in order to dynamize the masses artistically, the liturgical services, the liturgical acts, music was taught to the students and the priests.

Culture always starts with religion; religion a key to culture. This contributed a lot to, let’s say, a musical atmosphere that exists in Goa, through the priests. There are also lay people – so many lay people who have learned music and made their contribution. But then, that’s the role of the priests: each one in their respective parish builds the infrastructure of a parish choir. And the church choir is the group that gives musical support when the whole assembly sings.

O.N. But it’s not just the liturgy, it’s not just the parish; but in society, too, there are examples of how the church has contributed to Christianize certain local songs and dances…

E.M. Yes, it’s always so. In society there is always an interaction. There are the principles of the church… well, why can't you give it a very typical Goa look? For example, khell tiatr, which has music… it is always the music of the Christian community… let’s not forget that… so I would say religion has played an important and fundamental role in the formation of typical Goan music…

O.N. Exactly! And what are the initiatives of the modern church in Goa, towards dynamizing musical talent?

E.M. The Church of Goa has taken great care to see that the parts of the Mass, or liturgical acts, which include antiphons, and other musical things have musical backing. Hence, new melodies and arrangements are composed and new musical groups formed.

O.N. They say that our Gaionancho Jhelo is one of the best here in India…

O.N. They say that our Gaionancho Jhelo is one of the best here in India…

E.M. Yes, because Gaionancho Jhelo, above all, comprises many new lyrics and old lyrics, and everything is well tucked in a bouquet of very beautiful lyrics for use by the liturgy…

The Goan Motet

O.N. We cannot end without a word about the motet… Father, may I know what is the originality of the Goa motet!

E.M. First of all, the motets of Goa were composed in the same spirit in which the motets of Europe were composed. The motet of Europe was a song whereby people sang and at the same time reflected and ruminated on the biblical text relating to the respective feast. But in Goa the motets were limited to the Lenten season.

Now the Goa motets are not very difficult; they are beautiful and very well made. People who can read music can meet, and easily perform a motet. The musical accompaniment always includes violins, clarinets and the double bass…

O.N. In Europe, they were a capella…

E.M. Yes, but not all. For example, “Jesus, joy of man’s desiring”, by Bach, is a motet, as you know, from the feast of the Visitation of Our Lady…. The melody was simple. Bach’s contribution comprised the introduction that he wrote, and then he wrote an interlude and the final part, and that turned out into such a big piece. Therefore, it was a motet of the Visitation feast of Our Lady.

These motets of ours are just the same: a small musical motif, which has an accompaniment, and introduction of musical instruments; then they are sung, that is, repeated, then there is an interlude, and an ending. That’s it – the structure is very similar to that of the Western music motet, from the cathedrals of Europe.

O.N. Father, I’m afraid we’ve reached the end of our chat. Sorry to have to stop. But, before we close: you will certainly agree that the harvest is great, but the workers few…. What is your message to our people? What’s your plea?

E.M. First of all, thank you very much for this opportunity to speak here in your studio…

My message would be as follows: we are very proud to be musicians. Let’s uphold this tradition; let’s work in order that our new generation, our next generation, learn from what we do.

Now, there are so many young people in our parishes, whether or not they have a musical education, let’s give them the opportunity to be part of the choir, go there and learn a musical instrument, and come with that instrument to the church, and eventually on to the platforms offered to them.

My Stuti Choral Ensemble as well as the Goa String Orchestra will always be a platform for those who want to sing, each according to their ability… Come, you are always welcome!

I would love parents to take this task of taking their children to schools and showing them good musical programmes in our cities or elsewhere, such that younger people gain a taste for that, and then we would have a new generation of people.

O.N. Thanks again, Father Eufemiano, and long live the Goa String Orchestra and the Stuti Choral Ensemble! Thank you very much!

E.M. Thank you!

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa - II Série - N15 - Março Abril de 2022

All for the greater glory of God

What is our response to God who has lovingly revealed Himself in myriad ways on three successive Sundays? The Mass readings of today are an apt reminder of what should be our posture vis-à-vis the purpose of our existence.

In the First Reading (1 Kings 19: 16B, 19-21), we meet Elijah, a prophet who lived in Israel nine centuries before Christ. He defended Yahweh, the one true God of the Israelites, against Baal, a false god of the Canaanites. God worked miracles through Elijah as a sign that he was His favoured one. He was bodily assumed into heaven on a chariot of fire; and at the time of the Transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor, he too appeared, along with Moses. It is said that he will return before the last day, as a harbinger of the Saviour.

Before his departure, Elijah had made sure that Elisha would step into his shoes as prophet. The cloak thrown over Elisha symbolised the transfer of Elijah’s very persona, with all the rights and charisms of his vocation. Elisha spent some time on Mount Carmel (hence, a favourite with the Carmelites) where Elijah had once lived and challenged the prophets of Baal. Not everything that these two distinctive figures did is documented, but one thing is sure: they were clear about what was expected of them and faithfully carried out their missions.

How beautifully this links to the Gospel (Lk 9: 51-62), which urges each one of us to readily respond to God’s call, like Elisha did. Here, Jesus presents us with three injunctions, veritable pearls of wisdom; though not uttered in quick succession, in real time, St Luke stringed them together thematically. When Jesus was refused accommodation by a Samaritan village, in keeping with the customary animosity with the Jews, our Saviour commented on it pointedly, in three pearls of spiritual knowledge.

How beautifully this links to the Gospel (Lk 9: 51-62), which urges each one of us to readily respond to God’s call, like Elisha did. Here, Jesus presents us with three injunctions, veritable pearls of wisdom; though not uttered in quick succession, in real time, St Luke stringed them together thematically. When Jesus was refused accommodation by a Samaritan village, in keeping with the customary animosity with the Jews, our Saviour commented on it pointedly, in three pearls of spiritual knowledge.

The first of the pearls is a lament on how ‘foxes have dens and birds of the sky have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to rest his head.’ That is, while the least of creatures, if worldly-wise, are well received, those who have an other-worldly outlook, even if thinking logically and acting fairly, are made to feel unwelcome.

That is how fallen man behaves; hence the second pearl, in the form of a piercing arrow: ‘Let the dead bury the dead,’ says Jesus, and bids us to single-mindedly get going with God’s business. And then comes the third pearl, as a tough challenge: ‘No one who sets a hand to the plough and looks to what was left behind is fit for the kingdom of God.’ Jesus warns us against pinning our hopes on the world; we rather be steadfast in divine matters.

Meanwhile, will we ever overcome our innate love for the world and all that is in it? Is it possible to tread the path that Jesus points to? Will its difficult terrain not cause us untold hardship and misery?

We have it on excellent authority that God has called us for freedom – and only He can set us free! St Paul in the second Reading (Gal 5: 1, 13-18) says, ‘For freedom Christ set us free; so, stand firm and do not submit again to the yoke of slavery.’ The Apostle of the Gentiles, who had freed the Galatians from the oppressive Mosaic law, wanted them to hold fast to their newfound, Christian freedom that liberates one not only from the yoke of law but from the yoke of sin as well. Alas, how we underestimate that freedom!

On the other hand, how are we to conduct ourselves? Like Elisha, of course! He who heeded God’s call asked for time only to slaughter his oxen and burn the very plough. Elisha was in the right frame of mind; he trusted the Lord and renounced everything. For our part, how about asking for the gift of discernment to help us separate the wheat from the chaff?

Not that it will set us rolling on a comfortable highway; life will mostly likely remain the same narrow path it always is, filled with trials and tribulations. But surely, our slow and steady daily grind will liberate us from the yoke of egos and taboos; our suffering will gradually score a victory over evil tendencies, purify and sanctify us. And when we have run the race, having kept the faith, we will gladly have followed Jesus, who is the Way, the Truth and the Life.

Finally, if all of the above seems silly or extreme, consider why we find the world in a shambles today! It is because we have lost sight of the primary reason of our being, that is to seek God and know Him, to love God and serve Him, ‘above all nature and all created things.’ We have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. Let us, then, quickly turn around and live our lives ad majorem Dei gloriam – as the motto of Ignatian spirituality says – for the greater glory of God!

Bread Broken, Wine Shared

In June we celebrate three important solemnities – Pentecost; Holy Trinity; and the Body and Blood of Christ. These solemnities held on three consecutive Sundays form a kind of triptych drawing our attention to those central mysteries of our faith. The first solemnity helps us see the Holy Spirit at work in the Church; the second focusses on the Triune God whose Source is the Father; and the third highlights the Son’s Real Presence in the Eucharist. These solemnities are all so rich in meaning that if only we stopped to understand their significance, our faith could easily take on a deeper reality.

Today’s Solemnity, which used to be called Corpus Christi (Latin for ‘the Body of Christ’), is now known as the Body and Blood of Christ, more in keeping with the Eucharistic theology. Really speaking, the solemnity falls on a Thursday after that of the Holy Trinity; but, in India, both solemnities have been moved to the Sunday following, to enable a more worthy celebration. Similarly, the shadow of the Cross falling on the liturgy left little scope to celebrate the institution of the Eucharist on Maundy Thursday. Hence, way back in the 13th century, the Church had found it appropriate to bathe the solemnity in the paschal joy.

It is common knowledge that the pivotal Thursday of Jesus’ final Passover comprised a meal to mark the Jewish thanksgiving to God for delivering the people from slavery in Egypt. That meal, which has come to be known as the Last Supper, instantly assumed a new meaning when Jesus proclaimed a new commandment of Love; instituted the Priesthood; and established the Sacrament of Holy Eucharist. Thus, over and above the thanksgiving, the Eucharist is our participation in Jesus’ eternal Priesthood and a re-enactment of His Sacrifice on Calvary.

The multifarious connotations of the Eucharist are reflected in the day’s Readings. In the First Reading (Gen 14: 18-20), we meet a mysterious figure, Melchizedek, king of Salem (presumed to be Jerusalem) and priest of God Most High, on his way to bless Abraham who was returning from a just war. In his thanksgiving to God, Melchizedek offers bread and wine, a common food and drink for the Jews. Christian tradition sees Melchizedek as prefiguring Jesus, who is Priest, Prophet and King; and his offering, in the mould of the Eucharistic Sacrifice.

The Second Reading (1 Cor 11: 23-26) refers to the Eucharist instituted by our Lord. St Paul’s writing of circa A. D. 55 predates the Gospels and is the oldest testimony relating to the Last Supper. Jesus breaks the bread, symbolising His Body, and raises the Cup, symbolising His Blood. He does this for us in love beyond compare and bids us to repeat it as a memorial. So, there is an ineffable union with Jesus Who is present at every Eucharistic celebration.

Finally, St Luke’s Gospel (9: 11-17) talks about the remarkable meal that fed five thousand who had gathered to listen to Jesus. This is evocative of two passages from the Old Testament: the feeding of the Israelites in the desert and of Elisha’s feeding a hundred people with twenty loaves. They herald the Eucharist as food and medicine for the body and soul.

A deeper reality underlies the Holy Eucharist: the miracle of Transubstantiation. When the priest consecrates the Bread and Wine, ‘there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood.’ (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1376) The species do not change in appearance but turn into the very essence, reality and matter of the Lord’s Body and Blood. It is the Lord’s Real Presence – dwelt on by the encyclical Mysterium fidei.

The Eucharist is indeed a ‘mystery of faith’. St Thomas of Aquinas states that this ‘Sacrament of sacraments’ (CCC 1330) ‘cannot be apprehended by the senses but only by faith. Before him, St Cyril of Alexandria had advised: ‘Do not doubt that this is true; instead accept the words of the Saviour in faith; for since He is truth, He cannot tell a lie.’ (cf. CCC, 18) To those who seem unconvinced, the ‘Eucharistic Miracles’ are most likely to provide satisfactory proofs (cf. Eucharistic Miracles and Eucharistic Phenomena in the Lives of Saints, by Joan Carroll Cruz)

As we take a leap of faith and humbly surrender ourselves, the Lord of the Eucharist will reveal Himself to us sooner rather than later. The Eucharist, so rich in symbolism, will bring meaning to our lives. And as we gradually enter into full communion with Him and open ourselves to His Mystery, God will protect the sacred mystery of our lives. In the words of Pope Benedict XVI in his apostolic exhortation Sacramentum caritatis, ‘It is through the working of the Spirit that Christ himself continues to be present and active in his Church, starting with her vital centre which is the Eucharist.’ That's a wonderful lesson from June’s Mystery triptych!

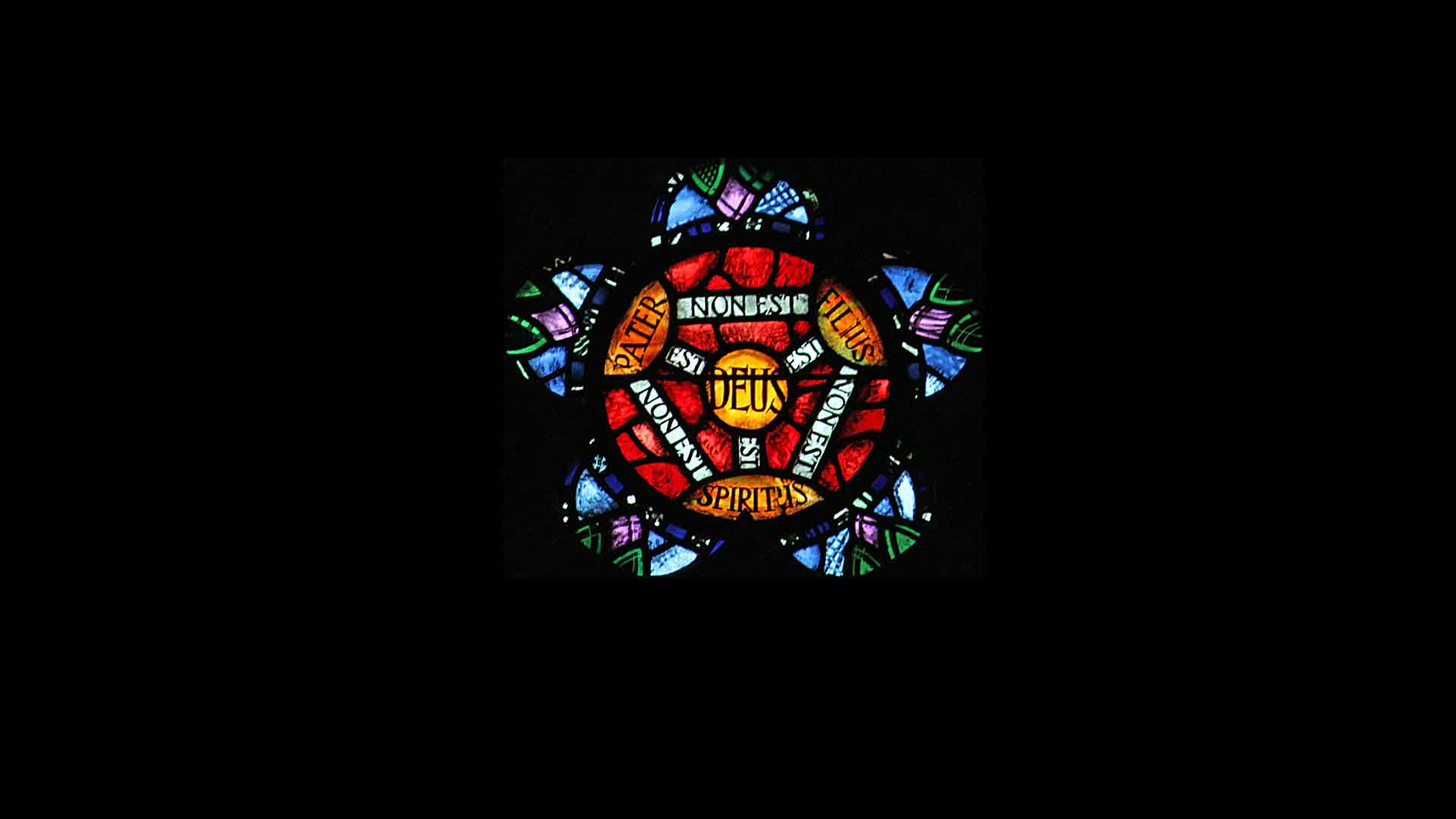

Discovery of God

On Pentecost Sunday, we gladly encountered the Holy Spirit. Now it is only natural that the Most Holy Trinity should be in full view. This is the Solemnity we celebrate today.

It may come as a surprise to many that it is not the Incarnation, nor even the Resurrection, but the Holy Trinity that is Christianity’s central mystery, from which flow all the other mysteries of our faith. It is a mystery that has existed since the beginning of times but has unfolded only gradually.

For instance, the Old Testament has references to the Three Persons but stops short of stating a Trinitarian doctrine. In the New Testament, Jesus pointed to His Father who loves us and desires our salvation; He presented Himself, the Son, as the Way, the Truth and the Life; and, before His departure from the world, He announced that the Holy Spirit would reside in our souls as a Guest. Yet, a doctrine of the Triune God was far from clear and remains to date just that: a mystery, a belief beyond our ability to understand unless God bares it to us.

None can deny, however, that the Trinity has been progressively revealed to humankind down the ages. It was not disclosed all at once, not only because of the finiteness of human minds, but because God patiently waits for us to exercise our freedom and come forward to learn about the intimate life of God. It is never an imposition; it is rather an invitation to establish personal ties with the three divine Persons.

That is what happened after Jesus. The early Christians felt it necessary to decode the Risen Lord’s instruction to make disciples of all nations, baptising them ‘in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit’. They also pondered St Paul’s blessing – ‘The grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all’ – now recited in the introductory rites of the Holy Mass. By and by, Biblical references to Father, Son and Holy Spirit were put together as a cohesive doctrine.

In spite of all that welcome research, the Holy Trinity remains the most difficult theme of our faith. Today’s Readings bear it out: they give only a glimpse, not a precise understanding of the mystery.

In the First Reading (Prov 8:22-31), we hear Wisdom rather than God the Father speak. Anyway, God – who has defined Himself as ‘I am who I am’ – is Himself Wisdom, and is it not more graceful to be introduced by another than to introduce oneself? So, it is age-old Wisdom presenting the Eternal Father to us. More importantly, we learn how He is not a distant God but One who delights in communicating with humankind.

In the Second Reading (Rom 5:1-5), St Paul talks of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, who gives us peace that no other can give. He also refers to the Father in whose glory we can hope to share by the merits of His Son’s Death. However, this supreme sacrifice has not eliminated human suffering from the face of the earth. The Apostle of the Gentiles urges us, therefore, to rejoice, for indeed, suffering produces endurance, character, and finally the hope of receiving a priceless grace: total communion with God.

In the Gospel (Jn 16:12-15), Jesus introduces to us the Holy Spirit, to whom He has entrusted the continuation of His mission till the end of times. The Son of God says, ‘I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now’; He leaves it to the Spirit of Truth to make things clear to those who yearn for the truth. And, whereas many things may forever remain a mystery, it behoves us to keep exploring that which has been revealed. At any rate, we who are created in the image and likeness of God have an infused knowledge and intuitively commune with the divine Family of Three.

What is the significance of today’s Solemnity? It reinforces our understanding of the Trinity. Our baptismal entry into this divine community deepens every time we gather around the Eucharistic Table. Today’s Liturgy is set to make us passionate about discovering our God. Our God is not a solitary Being lost in the dark and infinite space but a communitarian God of life and love, a model for the human family.

What is the significance of today’s Solemnity? It reinforces our understanding of the Trinity. Our baptismal entry into this divine community deepens every time we gather around the Eucharistic Table. Today’s Liturgy is set to make us passionate about discovering our God. Our God is not a solitary Being lost in the dark and infinite space but a communitarian God of life and love, a model for the human family.

No minds however great and no words however eloquent will adequately express this most complex of all Christian concepts and doctrines. The most popular story illustrating this fact is taken from thirteenth century Italian Dominican Jacobus de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea. Accordingly, St Augustine was walking by the shore, meditating on the problem of how God could be three Persons all at once, when he notices a little child scooping water from the sea into a small hole he had dug in the sand. When asked what he was doing, the child answered: ‘I’m emptying the sea into this hole.’ ‘What! The sea is too large for the hole,’ retorted Augustine. And pat came the child’s reply: ‘Indeed. But it is easier for me to empty the sea into this hole than it is for you to grasp the mystery of the Holy Trinity.’

At the time, St Augustine was working on De Trinitate (On the Trinity). He completed it, although not to his heart’s content, but never stopped discovering our many-splendoured God. Shouldn’t we take a leaf out of his book?

Ecstatic and fiery at Pentecost

After the Ascent came the Descent. Jesus ascended to the Father on the fortieth day after Easter; ten days later He sent forth His Spirit upon the Apostles, Mary, and other followers of Jesus, about 120 of them who had huddled up at the Cenacle in Jerusalem, for fear of the Jews. They had been continually praying for nine days since the Ascension. (Note that this marvellous event led to the idea of a novena as days of prayer leading up to a feast; and, in particular, the Novena to the Holy Spirit in the run-up to the Pentecost).

How delightful it must have been! That morning, God had timed the descent of the Holy Spirit to coincide with Shavuoth (Acts 2:1–31), which traditionally heralded the wheat harvest. In time, Shavuoth came to mean the seven weeks since the Passover; it was finally replaced by ‘Pentecost’ (from the Greek word pentēkostē, '50th'), which comprises the dramatic arrival of the Holy Spirit, as noted in the First Reading (Acts 2: 1-11). A sound from Heaven, like the rush of a mighty wind, filled all the house. Interestingly, spirit means both ‘breath’ and ‘wind’ in the Hebrew culture!

Even more striking were the tongues ‘as of fire’ that came to rest on each one of those Galilean disciples. Thus ‘ignited’, they began to speak in foreign lingoes, to the bewilderment of the motley crowd from every nation under the sun, who had gathered there on the occasion of the Jewish festival. That is the miracle of Pentecost, which indicates that God wishes to be followed and praised by people from every land and clime – unlike Jewish converts of old who had to promptly renounce their native language and culture.

The Second Reading (Cor 12: 3-7, 12-13) speaks of how the disciples built the Church. As St Paul says, ‘To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good... For by one Spirit we were all baptised into one body – Jews or Greeks, slaves or free – and all were made to drink of one Spirit.’ That is to say, Christians contribute their time and talent for the benefit of the community.

In the day’s Gospel (Jn 20: 19-23), the Holy Spirit gives the apostles gifts and fruits necessary to fulfil the great commission of going out, preaching the Good News of Salvation and being the light to all nations. The power to forgive sins is the greatest gift to the Church, which is never free from sinners.

The Church thus built is the ‘Mystical Body of Christ’, mystical because, in Fulton Sheen’s words, ‘this Body is not physical like a man, nor moral like a bridge club, but heavenly and spiritual because of the Spirit which made it one.’ That it is ‘Christ’s prolonged Self’ can be proved from the Voice from Heaven that said, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ ‘When the Body of Christ was persecuted, it was Christ the Invisible Head Who arose to speak and to protest,’ writes Sheen in his Life of Christ.

The Church thus built is the ‘Mystical Body of Christ’, mystical because, in Fulton Sheen’s words, ‘this Body is not physical like a man, nor moral like a bridge club, but heavenly and spiritual because of the Spirit which made it one.’ That it is ‘Christ’s prolonged Self’ can be proved from the Voice from Heaven that said, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ ‘When the Body of Christ was persecuted, it was Christ the Invisible Head Who arose to speak and to protest,’ writes Sheen in his Life of Christ.

Can there be any doubt that the Church born at Pentecost is the Church we belong to? She enjoys four distinctive marks of life: unity; catholicity; holiness; and apostolicity. The Church is animated by one Spirit; she absorbs and redeems humanity without distinction of race or colour; she is holy as a whole, even if her individual members are diseased; she is apostolic, because she took roots in Christ and her ministry derived from the apostles by a continuous succession.

The deeper significance of Pentecost is that Jesus, who once ‘emptied Himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men’, thereby received His fullness and was glorified. He now lives, teaches, governs and sanctifies us, better than He did in Judea and Galilee – for, as Son of God seated at the right hand of the Father in Heaven, He can reach out to the whole world better than He could when He walked the earth as Son of Man.

Pentecost was an important event in the history of the primitive church and continues to be so in our own times too. After Peter preached his first homily to the Jews and others, showing how Joel had prophesied the coming of the Holy Spirit, about 3,000 people – cut to the heart by the Crucifixion and enthused by the Resurrection of Our Lord – asked for baptism. Within a few decades important congregations were established in major cities of the Roman Empire. It is not difficult to understand how, centuries ago, our own ancestors, attracted by the Mystical Body, the Bride of Christ, converted to the Christian faith.

What about today? The stronger our adherence to the Church, the quicker will be the spread of Christianity. Can we imagine ourselves being born outside the Church? No. Let us, then, honour the glorious birthday of the official Church. It is a gentle movement of hearts that still brings together people formerly separated by languages, cultures, races and nations, and will culminate in the Second Coming of Christ. Let’s commit ourselves to putting our lamps on a high stand such that it shines upon all that are in the house. Reaching out to people from the seven corners of the world is a continual challenge. Let’s be ablaze with love of God and neighbour, and pray, ‘Send us, O Lord, your Spirit, and renew the face of the earth!’