Carta ao Primo Mário

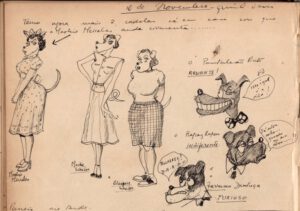

Mário Miranda, meu primo e grande amigo, o que é que eu posso dizer a teu respeito que as pessoas ainda não saibam? Quando nos deixaste, já eras quase mundialmente conhecido, assim como os teus trabalhos de caricaturista e os outros mais sérios. Mas é essa tua faceta de caricaturista que eu quero recordar aqui nestas poucas linhas.

Eras um artista nato e, até um certo ponto, um autodidata. Tinhas o condão de nos fazer rir e soltar umas boas gargalhadas, mesmo sem escrever ou pronunciar uma única palavra! Bastava-nos olhar para as tuas caricaturas para desatarmos a rir e de cada vez que olhávamos para elas, encontrávamos sempre novos motivos de riso.

Sempre foste de poucas palavras, mas, em compensação, tinhas um poder de observação fotográfico que, mais tarde, transferias para os teus diários. Eu ficava admirada com este teu dom e perguntava-me como é que o Mário consegue reter na sua memória tanta coisa e com tantos detalhes que ele mostra nos seus desenhos? Só um génio ou uma pessoa privilegiada o consegue e tu eras um privilegiado nesse aspecto e eu sempre te admirei muito por isso.

As tuas caricaturas são de um realismo tal, que as pessoas por ti caricaturadas parecem seres vivos em miniatura, prontos a saltar do papel para o nosso colo! E a semelhança é de tal ordem, que podem ser facilmente reconhecidas e identificadas, mesmo tratando-se de desconhecidos…

A propósito vou contar um pequeno episódio passado comigo. Havia um senhor cujo nome não me ocorre agora, mas que podemos chamar o senhor ABC e que tu representavas nas tuas caricaturas com uma certa frequência. Um belo dia em que eu estava em Damão fui visitar a senhora Dona Bolina, a tua avó materna e, qual não foi o meu espanto, quando eu ia a entrar e vi sair de lá esse tal senhor, que para mim era um ilustre desconhecido! Não resisti à curiosidade e perguntei-lhe se ele era, por acaso, o senhor ABC. E ele respondeu-me: “Sou!” e, acto contínuo, com um ar muito espantado, perguntou-me de onde é que eu o conhecia ao que lhe respondi que era do Diário do Mário!

Lina*

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* Maria Carolina Miranda Bordadágua n asceu em Pangim, Goa, em 1925, e ora vive em Lisboa. Fez o curso no Liceu Afonso de Albuquerque em Goa e o BA em Bombaim. Foi Professora de Português, Inglês e Francês no Liceu Nacional Afonso de Albuquerque. É viúva do Coronel do Exército António da Graça Bordadágua e mãe de Luís Filipe Miranda Bordadágua e de Maria Margarida Miranda Bordadágua.

asceu em Pangim, Goa, em 1925, e ora vive em Lisboa. Fez o curso no Liceu Afonso de Albuquerque em Goa e o BA em Bombaim. Foi Professora de Português, Inglês e Francês no Liceu Nacional Afonso de Albuquerque. É viúva do Coronel do Exército António da Graça Bordadágua e mãe de Luís Filipe Miranda Bordadágua e de Maria Margarida Miranda Bordadágua.

Reconhecimento: Artigo publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 12, Set-Out 2021.

A Road Well Taken

Selecting the right path, both literally and figuratively, is the central theme of American poet Robert Frost’s ‘The Road Not Taken’. The poem was prompted by the continual state of indecision faced by an English writer-friend of his. When the two went for walks, his friend always found it difficult to choose a route, and even after all that fuss was over, he sighed over the opportunities missed on the other route.

The poem popped into my mind as I was going through the Mass readings. We have Isaiah (6:1-2A, 3-8), Paul (1 Cor 15:1-11) and Peter (Lk 5:1-11), three Biblical heavyweights. Like Jeremiah last Sunday, they too faltered at first, then made a leap of faith. They received their calls quite differently but, animated by the love of God, they had the same goal in mind. And unlike the man in the poem, they never regretted the road they had taken. In fact, they were convinced, they persevered under trials, and received the crown of life.

Isaiah receives his prophetic call at the feast of Atonement. In the temple, he had visions of the heavenly court. He did not get to see God face to face; he only glimpsed the train of his garment and heard the quake and the smoke – signs of God’s presence. As he heard the angels sing the Sanctus (the same that we now hear at Mass) he began to feel anxious about his sinful state vis-à-vis God’s presence. He anticipated death but instead was healed by the touch of a burning coal. Fired thus with God’s spirit, he gave his fiat: ‘Here I am! Send me!’

Isaiah was ready to go as God’s messenger, and so was Saul after he became Paul. Initially a persecutor of the Christians, Paul’s dramatic encounter with Jesus on the high road to Damascus changed it all. He offered himself without reservation to God’s service. He undertook four missionary journeys and came to be called ‘Apostle of the Gentiles’. And as there were misgivings about Jesus’ death and resurrection, Paul proclaimed it as an undeniable fact and, for him, a life-changing experience. About the Resurrection, which is at the heart of the Christian message, Paul said emphatically that, without it, ‘our faith is futile’.

Whereas Isaiah was timid, and Paul who was conceited became humble after his personal experience of God, Simon Peter for his part was a rustic character. Jesus, however, did not look at his intellect but at his heart. A fisherman and unlettered though he was, Jesus made of him a fisher of men. Peter eventually became greater than all men of letters put together, schooled as he was in the knowledge and the love of God. He was in awe of Jesus, and on hearing His soothing words – ‘Do not be afraid. You will catch people from now on’ – Peter and his fellow fishermen James and John left everything and followed Him.

You and I, who are called to live out our baptismal vocation of priest, prophet and king, where do we stand? Do we believe that we should leave everything and follow Him? Or, do we, like the poet, see two paths, unsure which to choose?

Really speaking, Christians have only one path before them: to be messengers of God’s salvation and grace by the apostolate of presence. We are called to be the light of the world and the salt of the earth, such that the temporal is soaked in the Christian spirit. Indeed, we must not let ourselves be blinded by the city lights; we must not be lured by ideologies that lead us astray from the path of truth and justice; we must rather be committed to the only life-giver, Jesus Christ. He is the Way, the Truth and the Life. He shows us the road to Eternal Life. This cannot but be a road well taken.

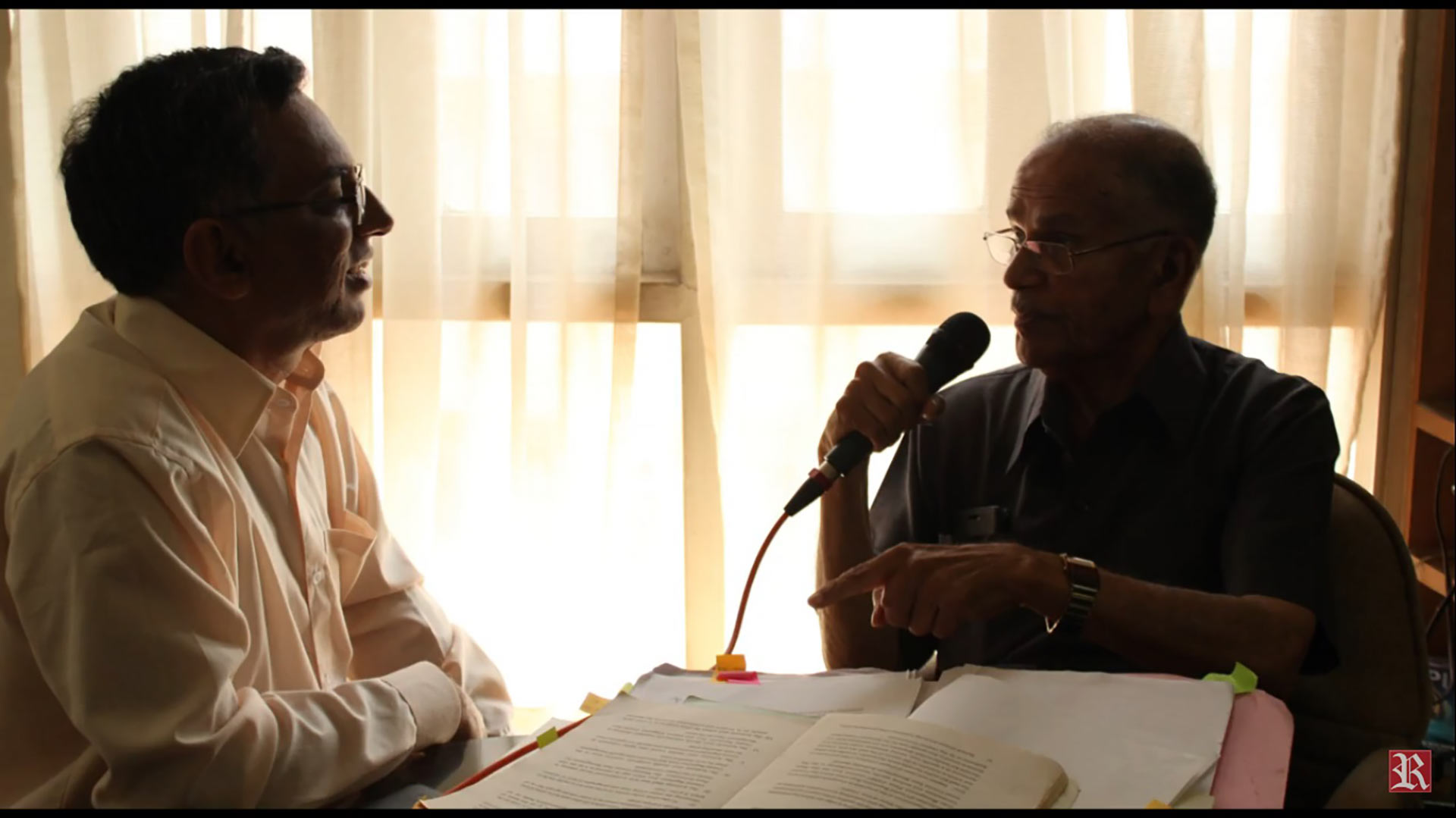

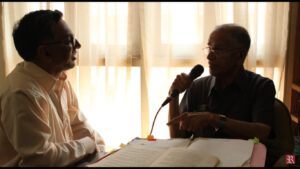

"My dream is to see Goa’s Civil Code extended to the Indian Union," says M. S. Usgaonkar

February 4, 2022Seabra,Y. V. ChandrachudInterview,Law

ON: What does the ‘dream’ that you talk of in the Preface to your book mean to you and to our territory?

MU: Well, before I talk about my ‘dream’ I would like to clarify that when Seabra’s Civil Code [1867] was published, it did not have the chapters that I am going to stress on, as these were fruits of the Republic in 1910. Thus, the Portuguese Civil Code was a product of the Constitutional Monarchy; the law of Marriage, the law of Divorce and the law for the protection of children were specialties produced by the Republic. The Portuguese Civil Code did not have the concept of divorce; it simply dealt with the absolute separation of property.

ON: According to you, why didn’t Seabra introduce Divorce and, instead, dealt only with Separation? Was it through the influence of the Catholic Church?

MU: I don’t think so… The concept did not exist at the time. Divorce evolved much later.

ON: So, in 1910 all communities had access to the law of divorce...

MU: Yes; but the Church prohibited it, because one of the Articles states: those marrying through the Church are not entitled to divorce. This provision was later stuck down by our Courts because one could not discriminate between two communities.

ON: Well, the Civil Code would not discriminate between communities, yet it appears that the usages and customs only of certain communities were safeguarded in the Code....

MU: This was not about the usages and customs; this was a part of the law. Divorce (earlier it was Separation) was made part of the special legislation that came into force in 1910, after the Republic.

ON: Could you throw light on the usages and customs that were safeguarded?

MU: They were excluded in 1880, that is, before the Republic.

ON: Some examples of what was safeguarded…

MU: For example, one could marry at a predetermined age, which was reduced. Later, this law was extended to the Catholics also, because they pointed out that there was a tradition or custom to marry at an early age and that was permitted by the State.

ON: What was the age?

MU: The girl could marry at the age of fourteen.

ON: And the boy?

MU: At the age of sixteen.

ON: Is it true that members of the Hindu community were permitted to have more than one wife?

MU: There was a restriction. It required the consent of the earlier wife; and she had to be childless. Only then the second marriage was permitted; but this was struck down by the Portuguese law in the year 1952, on the grounds that polygamy had long been abolished.

TRANSLATING THE CODE

ON: Let’s talk a little about your translation: how long did it take you?

MU: Not long… just twenty years.

ON: Twenty years!

MU: Well, the total number of Articles of the Civil Code is 2538. There is also the Civil Procedure Code and miscellaneous legislation regarding the usages, customs and others which total up to more than 4000 Articles.

ON: So, yours is a translation of the whole of the Portuguese Civil Code…

MU: Not only of the Code but also of other laws that were published later…

ON: … which are connected to the Civil Code and to the Civil Procedure Code…

MU: Yes, the Civil Procedure Code, too, which has 1580 Articles. The reason for translating both the Codes is that the Civil Code alone is not sufficient; the Civil Code provides only the substantive aspect of law, but the enforcement or implementation is done through the Civil Procedure Code. Courts and others must follow the Civil Procedure Code, so the Codes are complementary.

The Code of Civil Procedure was repealed in the year 1939; the whole of it was the work of Prof. Alberto Reis and it was in force at the time of Liberation… At a conference at Simla, organized by advocates from the Indian Union, I had the opportunity to highlight the advantages of the Portuguese Civil Code and how it serves to decide cases much faster.

ON: But in Goa today only a part of the Portuguese Civil Code is in use, isn’t it?

MU: It was in use, but later it was gradually substituted by corresponding Indian laws.

ON: Which are those laws?

MU: For example, the Transfer of Property Act, Contract Act which formed an integral part of the Civil Code stood pro tanto altered.

ON: So, today, the Code is in use mainly regarding family laws…

MU: Yes, the law of marriage and divorce is unaltered. Fortunately, what existed here was repealed neither by the Union of India nor by the State government, except that every time an Indian law was introduced, the respective provision of the Civil Code was repealed. For example, the law of pre-emption… when an individual sells his right without giving preference to the co-owner. This is not provided for in the same way under the Indian law. The problem which arose was to see whether this provision of Portuguese law prevails or not. The courts said that it does prevail since a similar provision does not exist in the Indian Civil Code.

ON: In Portugal, is the same Civil Code still in use?

MU: No, it was changed entirely, in 1966, influenced by the Germanic theory… When Napoleon Bonaparte prepared a Code and appointed persons, he said that the Code had to use simple language, such that the public could easily read it. In contrast, the Germanic jurists said that eventually only the jurists should read the Code and not the public.

GOAN CONTRIBUTION

ON: This Code is a Portuguese legacy, but Goa is also connected to the Code, through a Goan – Luiz da Cunha Gonçalves – who has contributed a lot, thanks to his Treatise on Civil Law... Would you like to throw some light on this jurist?

MU: Of course! He writes in the Preface to the first volume: “More than sixty years have elapsed since the publication of our Civil Code, but whereas in the interim period many treatises and commentaries have been published in the main countries of Europe, especially in France and Italy, here in Portugal the scientific work in this branch of legal science has been scarce, fragmented, superficial, nothing to compare even with the treatises of French classics, nothing on a par with the modern treatises. It was therefore imperative that alongside our Civil Code, one of the best in the civilized world, an intensive and extensive work should emerge, of the kind that I have referred to. Nobody will fail to acknowledge it, and convinced that I will be rendering good service to the Portuguese legal science and the country, I will not hesitate to try and execute the work, presuming that I will be helped by ingenuity and art.”

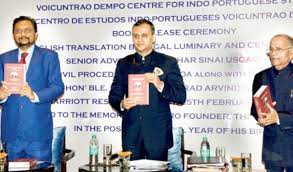

ON: It is evident from the host of names featuring in your book, right from the Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India, that your book and your translation of the Portuguese Civil Code did evoke a lot of interest…

MU: Yes, Justice Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Justice Couto and others have appreciated the translation. I can say that one who was really in favour of the Civil Code for Goa, Daman and Diu was Justice Chandrachud. He appreciated the law which existed, especially those three volumes, Marriage, divorce and Law for children, and he said thus: “The Uniform Civil Code remains today a distant world. In my view it would be a retrograde step if Goa, too, were to give up uniformity in its personal laws which it now possesses. Fortunately, as it appears now, the Portuguese followed a different policy in the matter of personal laws than the British. The Civil Code enacted by them covering inter alia family laws applied to all the communities living in this Union Territory except that the customs and usages of non-Christians were saved to a very limited extent. I am quite aware that the Uniform Civil Code of Goa, though it provides an ideal for the rest of the country, creates problems for the Union Territory of Goa itself. The special family laws operating in Goa which are different from those which operate in the rest of the country give rise to the peculiar inter-state conflicts of law. But this did not despair us because inter-state conflict of laws is one of the most perplexing aspects of American Federalism. The conflicts could be minimized by bringing the Portuguese Civil Code in line with some of the central statutes on the subject, at least in basic matters.”

ON: The Constitution of India states that the Civil Code ought to be introduced in India… You have been the Additional Solicitor-General of India. Do you think that the present social climate is favourable, and there have been efforts in that direction, or does the directive remain merely in the pages of the Constitution?

MU: Frankly speaking, till today no steps have been taken. It is an embarrassment to note that even after sixty years nothing has been done. However, the outcome of the Portuguese law was considered when there was a conference between Portugal and Goa, and judges and professors from different universities came here, and everybody spoke and appreciated the existence of the Civil Code. The conference took place when I was the Additional Solicitor-General of India.

ON: Oh! So, it was a very special event and an important step!

MU: After Independence or Liberation, as they call it, Parliament enacted a law, and it was mentioned that all the laws which are maintained are Indian laws. That was thus the first step for the maintenance of those laws – they could be repealed later, but fortunately till today the laws on marriage, divorce and [laws for] children have not been altered by the state. I have to say that there were efforts to discard it but what mattered was what the then Chief Justice of India Justice Chandrachud said: “It is heartening to find out that the dream of the Uniform Civil Code in the country finds its realization in the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu. How many outside are aware of this I cannot guess.”

DREAM

ON: Senhor Doutor, one last question: we have seen that the Civil Code is a legacy of the Portuguese. For your part, the translation of the Code is your legacy to the Indian Union.

MU: Yes, exactly. For as long as I live, it is my obligation to work to ensure that it shall continue.

ON: You were speaking of your dream: when would your dream be fulfilled?!

MU: My dream has three facets: first, the marriage must be compulsorily registered before the Civil Registrar, and this gives protection to the family. In the rest of India, this is done before the Hindu priest (Bhat), but it does not serve any purpose. Second, the regime of communion of properties, too, does not exist in the rest of India, and the third: reservation of the disposable share of legitimes is a system which maintains the balance, because half-share is reserved for the family and other half can be disposed of by the testator to whosoever he or she wants.

By introducing the legislation which is in force in Goa, Daman and Diu, justice can be done to all, and the interests of the children and wife can be protected. The concept of moiety which exists as per Portuguese law is recognized under section 5A of the Income Tax Act. This law is maintained by the Indian Union, and the payment of Income Tax by Goans is made, with due regard to the regime of communion of assets, as contemplated by the Portuguese Civil Code.

ON: But it seems that during the last two or three years there have been some problems in this respect.

MU: What problems?

ON: The Income Tax officers do not accept this concept of division of assets.

MU: It is not permissible to ignore the legislation; in fact, it is a violation of the law.

ON: They say that one cannot make a special provision only for Goa...

MU: They cannot be fail to comply with section 5A of the Income Tax Act. In fact, one of the Income Tax officers appreciated it and his subordinates did not want to accept it. He said thus: “If you do not accept, I will insist on making it applicable for the whole of India.”

ON: This brings us to our last question: the beautiful dream you have for India, when do you think it will come true?

MU: I do not know, but, frankly, I am trying to see that my dream is fulfilled. I will continue working till the end.

ON: Senhor Doutor, let me take leave of you, wishing you good health and many more years of work in this field. Thank you very much.

Acknowledgement:

(1) For original chat in Portuguese, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i62XuPeTQuc (2) Translated by Tolentino António Colaço (3) Chat show photographs by Emmanuel de Noronha (4) First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 13, Nov-Dec 2021, https://casadegoaorg.files.wordpress.com/2022/01/revista-da-casa-de-goa-ii-serie-n13-novembro-dezembro-de-2021.pdf

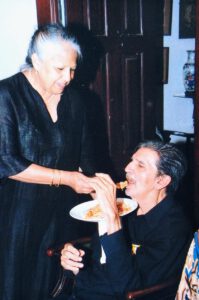

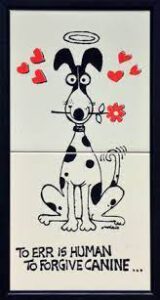

Último olhar às preciosas mãos

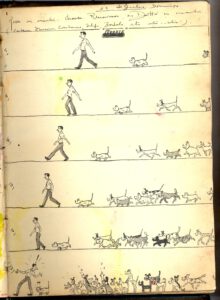

“Errar é humano, perdoar é canino”, dizia o Mário numa pequena publicação comemorativa dum Canil, algures na Índia, por ele ilustrada.

“Errar é humano, perdoar é canino”, dizia o Mário numa pequena publicação comemorativa dum Canil, algures na Índia, por ele ilustrada.

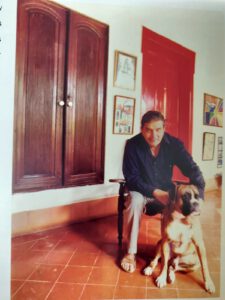

O amor e afeição que o Mário tinha para com os animais só se podia igualar com os sentimentos da Mãe dele. Lembro-me que em Borim depois de se atravessar a ponte metálica sobre o Zuari, a carreira, rumo a Pangim, parava por algum tempo para receber mais passageiros numa viatura já superlotada. Nessa paragem, além de vendedores de fruta, lanhas, bebidas gasosas e fios de zaiôs (uma variedade de jasmim) que vinham junto à viatura, também apareciam periquitos engaiolados. A minha Mãe comprava esses pássaros, soltava-os e devolvia as gaiolas ao radiante vendedor que podia apanhá-los e vendê-los novamente! Outrossim, no enclave de Cabinda, os nossos gatos siameses eram mimosiados com atum fresco do oceano Atlântico, que se arranjava raramente e com bastante dificuldade, enquanto o genro tinha que se contentar com nosso limitado estoque de sardinha enlatada! Isso porque em Angola faltava toda espécie de géneros alimentícios e de combustíveis, após a Revolução de 1974 em Portugal.

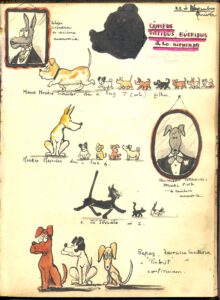

Em Loutulim, tínhamos um mini aviário, mormente para ovos. A maioria das galinhas eram batizadas pelo Mário. Uma delas, que aparecia sempre ao pequeno almoço, era a Madame Frufru. Quando uma dessas aves, ou um galo a mais, era transformado em caril de Goa ou dampaca de Damão, o Mário não tocava no prato. A desolação era também intensa quando algum dos nossos muitos caninos rendiam a alma ao Criador. Lembro-me vivamente quando o nosso altivo Rapaz Rodrigues Raposo e o ilustre Farrusco Santana Dentuça nos deixaram após bastantes anos de fiel e alegre companhia, incluindo nos passeios do Mário na aldeia. Recordo-me que naqueles dias tristes o Mário não fez nenhuma refeição, fechando-se no quarto, que mais tarde viria a ser o seu estúdio de trabalho.

Em Loutulim, tínhamos um mini aviário, mormente para ovos. A maioria das galinhas eram batizadas pelo Mário. Uma delas, que aparecia sempre ao pequeno almoço, era a Madame Frufru. Quando uma dessas aves, ou um galo a mais, era transformado em caril de Goa ou dampaca de Damão, o Mário não tocava no prato. A desolação era também intensa quando algum dos nossos muitos caninos rendiam a alma ao Criador. Lembro-me vivamente quando o nosso altivo Rapaz Rodrigues Raposo e o ilustre Farrusco Santana Dentuça nos deixaram após bastantes anos de fiel e alegre companhia, incluindo nos passeios do Mário na aldeia. Recordo-me que naqueles dias tristes o Mário não fez nenhuma refeição, fechando-se no quarto, que mais tarde viria a ser o seu estúdio de trabalho.

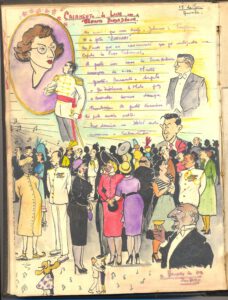

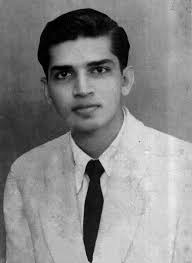

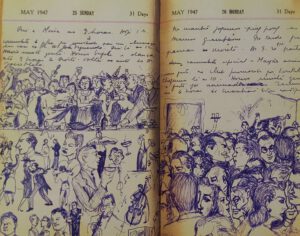

Esse mesmo amor o Mário dedicou à sua arte nata, que se desabrochou graças a embirração da nossa Avó paterna com os rabiscos dele nas paredes da casa. A Mãe, para acalmar os ânimos da sogra, deu um diário ao Mário, sugerindo que ele desenhasse todos os dias algum acontecimento interessante. Essa simples ideia materna foi o início, aos 7 anos, da carreira artística deste jovem envergonhado, de poucas palavras mas com piada, e com um dom de observação quase sobrenatural. Um dia o Mário disse-me: “O meu trabalho é uma constante oração”.

Esse mesmo amor o Mário dedicou à sua arte nata, que se desabrochou graças a embirração da nossa Avó paterna com os rabiscos dele nas paredes da casa. A Mãe, para acalmar os ânimos da sogra, deu um diário ao Mário, sugerindo que ele desenhasse todos os dias algum acontecimento interessante. Essa simples ideia materna foi o início, aos 7 anos, da carreira artística deste jovem envergonhado, de poucas palavras mas com piada, e com um dom de observação quase sobrenatural. Um dia o Mário disse-me: “O meu trabalho é uma constante oração”.

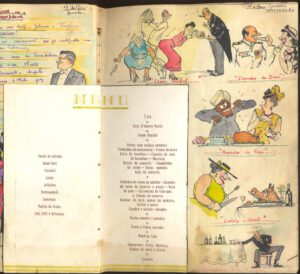

Os diários que a Mãe passou a oferecer-lhe no Natal de cada ano, mais tarde em papel de desenho, especialmente encadernado em Pangim, levando o ano e o nome na lomba, passavam de mão em mão dos primos, dos amigos e mesmo do Governador e Patriarca. Lembro-me do Patriarca D. José da Costa Nunes, que, segundo consta, deleitava-se com as caricaturas dos clérigos.

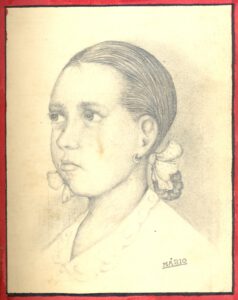

Quando jovem, o Mário tinha uma cabeleira bem espessa e um dos meus passatempos era fazer pequenas tranças do seu cabelo, enquanto ele registava acontecimentos no seu Diário. Nunca se aborreceu nem parou de desenhar. Nota-se que eu tinha apenas 5 ou 6 anos e ele estava já nos estudos universitários. Possuía o dom de trabalhar e conversar simultaneamente. Um dos outros passatempos, mas esse proporcionado por ele, era o piano, que aprendeu com a Mãe, e que eu ouvia com grande admiração. Imaginava-se pianista concertista fazendo vénias aos calorosos aplausos dos espectadores! Nunca pensou que iria fazer uma carreira como caricaturista, graças aos Diários que lhe abriram as portas.

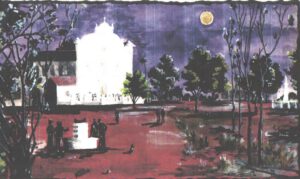

O Mário não foi apenas caricaturista. Tem uma imensidão de obras sem caricaturas. Quase no fim da vida produtiva, concordou que os pequenos traços com os quais criava imagens monumentais teriam sido uma autoterapia inconsciente. Nunca posso cessar de admirar o volume do seu trabalho. Se pensarmos nas 365 entradas no diário, ao longo de pelo menos 18 anos, temos 6,570 desenhos compostos de caricaturas, retratos, pinturas de paisagens e figuras a cores. Ele também redigia com bastante humor. Pena que o tempo não lhe permitiu desfrutar mais desse seu outro dom.

O Mário não foi apenas caricaturista. Tem uma imensidão de obras sem caricaturas. Quase no fim da vida produtiva, concordou que os pequenos traços com os quais criava imagens monumentais teriam sido uma autoterapia inconsciente. Nunca posso cessar de admirar o volume do seu trabalho. Se pensarmos nas 365 entradas no diário, ao longo de pelo menos 18 anos, temos 6,570 desenhos compostos de caricaturas, retratos, pinturas de paisagens e figuras a cores. Ele também redigia com bastante humor. Pena que o tempo não lhe permitiu desfrutar mais desse seu outro dom.

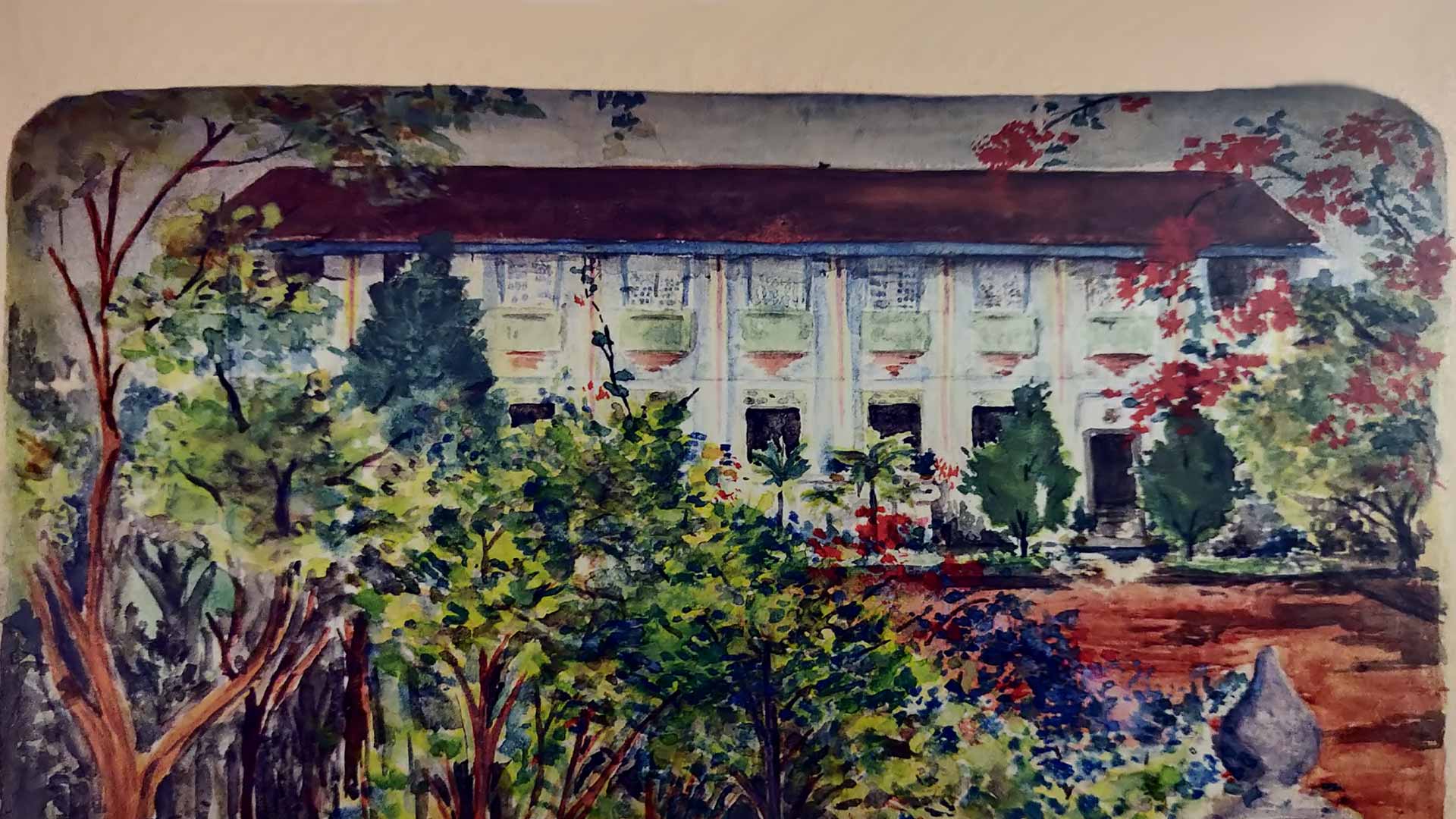

Desabafou um dia que queria ter tempo para fazer o que mais gostava: experimentar cores pintando a natureza em aguarela. Constantes prazos a serem cumpridos para o ganha-pão não o tinham ainda permitido esse luxo. A rigidez nas mãos impediram mais obras. Contudo, fez várias tentativas a lápis e aguarela, sendo cinzento claro a cor dominante, assemelhando nuvens, com pequenas manchas em rosa leve. Observação minuciosa desses borrões cinzentos, junto das manchas rosas, via-se o que parecia mini escaleres. Talvez recordação de Damão, sua terra natal. Não sei qual foi a sorte desses últimos trabalhos desse génio. Quiçá a mesma que dezenas deles tiveram quando o Tommy, o grande amigo canino, resolvia censurar aqueles que ele encontrava no chão do estúdio no apartamento em Bombaim, levantando a perna!

Desabafou um dia que queria ter tempo para fazer o que mais gostava: experimentar cores pintando a natureza em aguarela. Constantes prazos a serem cumpridos para o ganha-pão não o tinham ainda permitido esse luxo. A rigidez nas mãos impediram mais obras. Contudo, fez várias tentativas a lápis e aguarela, sendo cinzento claro a cor dominante, assemelhando nuvens, com pequenas manchas em rosa leve. Observação minuciosa desses borrões cinzentos, junto das manchas rosas, via-se o que parecia mini escaleres. Talvez recordação de Damão, sua terra natal. Não sei qual foi a sorte desses últimos trabalhos desse génio. Quiçá a mesma que dezenas deles tiveram quando o Tommy, o grande amigo canino, resolvia censurar aqueles que ele encontrava no chão do estúdio no apartamento em Bombaim, levantando a perna!

O último companheiro canino em Loutulim foi o Happy, nome dado pelo seu neto. Este, aliás alegre canino, traumatisado com a imobilidade do Mário, tentava saltar para junto do seu corpo, gemendo. Olhando pela última vez aquelas bonitas e preciosas mãos, ora atadas como que em prece, fiz com que o fiel amigo dele me acompanhasse para um passeio junto à Natureza, tanto apreciada pelo Mário, cogitando que afinal tudo o que é bom dura tão pouco.

Baizu, Biggle, irmã do Mário Miranda*

(Imagens: www.mariodemiranda.com)

* Maria de Fatima do R B M Figueiredo (1942-), natural de Bangalore. Meio século de trabalho: Portugal, Angola, Reino Unido, em diversas empresas particulares, consulado, embaixada e escritório de advogados. Actualmente em Goa com marido, no novo avatar como agricultores.

* Maria de Fatima do R B M Figueiredo (1942-), natural de Bangalore. Meio século de trabalho: Portugal, Angola, Reino Unido, em diversas empresas particulares, consulado, embaixada e escritório de advogados. Actualmente em Goa com marido, no novo avatar como agricultores.

The Splendour of our Vocation

Today we have a feast of scriptural texts about our prophetic vocation: Jer. I, 4-5, 17-19; I Cor. 12, 31-13 13; Lk 4, 21-30.

Years ago, I froze in my tracks when I heard God’s words to Jeremiah: ‘Even before I formed you in the womb, I have known you; even before you were born, I had set you apart, and appointed you a prophet to the nations.’ There is, undeniably, a rare touch of intimacy here that makes us feel special; but do those words also place a heavy responsibility on our shoulders, holding us accountable for our role as prophets?

On the other hand, without that bolt from the blue, wouldn’t we end up becoming complacent, lukewarm, mediocre? When God’s voice resounds in our minds and hearts, we are in awe of His majesty and mystery. His declarations also provide the shot in the arm that we so badly need, timid and weak as we are, and at risk, too, like Jeremiah was. God’s promise, then, to make of us ‘a fortified city, a pillar of iron with walls of bronze…’ feels so good and changes everything.

There is no denying that without aid from above, we are nothing. Notice the distressing experiences Jesus underwent in his hometown Nazareth. At first, ‘all agreed with Him and were lost in wonder, while He kept on speaking of the grace of God.’ They just stopped short of recognising His divine origin. And no sooner had they heard hard truths proceeding from the mouth of the Son of God, they became indignant and were even ready to throw Him down the cliff.

That’s a huge eyeopener; the nature of the public ministry and the ways of the world can indeed be baffling. Yet, we have to keep going; we have nothing better to do than what God has whispered in our ears. He expects no superhuman effort, nor should we expect to achieve success as the world looks at it; it just suffices to exercise our apostolate where we are planted. The only ammunition we need to carry is Love. No language, no prophecy, no knowledge, nothing can get round the devious ways of the world as love can.

St Paul’s ode to love is one of the most sublime of Christian texts and Jeremiah’s testimony one of the most impressive as regards the Christian vocation. Interestingly, they are both quoted at nuptial masses – for, after all, marriage is a very special vocation! It is no doubt fraught with risk and challenges, but then, very few are known to have given up before the miracle happened. Jesus too didn’t give up on His Bride, the Church. Why should we give up on the Church, our Mother, and all that she teaches us?

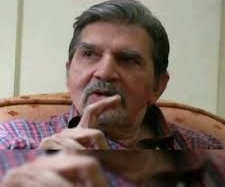

Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 6/6)

January 29, 2022Padma Vibhushan,Commander of the Order of Prince Henry,Padma Bhushan,Portugal's Medal of Cultural Merit,Awards,Goa State Cultural AwardBiography

Legacy

Money, power and fame meant little to Mário; he felt humbled by recognition coming his way. The Indian Government conferred two civilian honours upon him: the Padma Shri in 1988 and the Padma Bhushan in 2002. In 2007, he received the Goa State Cultural Award. In 2009, King Juan Carlos bestowed on him the Cross of the Order of Isabel the Catholic, Spain’s highest civilian honour; and Portugal knighted him as Commander of the Order of Prince Henry.

Despite his celebrity status Mário was a self-effacing person. Crafting a lighter finale to his twilight years, he returned to his watercolours and his piano. His sister Fátima notes that in his attempts at nature drawing, the dominant colour was a light grey, resembling clouds, interspersed with spots of light pink.[88] But he gave it up when he fell victim to Parkinson’s – stopping short of that one brushstroke that might create a blob and spoil the painting!

Although a little dispirited, Mário ploughed on. He rarely missed a music show or dining out; a sporadic religious event at home or a chance meeting with an old acquaintance could easily moisten his eyes. He kept in touch with old friends and new, remaining his shy and wry self to the very end.

The sad finish came but gently, in his sleep, on 11th December 2011. His earthly journey concluded with a requiem mass at the parish church of the Saviour of the World, Loutulim. He was cremated in Margão and his ashes strewn over the Zuari at Rachol.

Tributes kept pouring in. In 2012, Mário was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second highest civilian award. On his 90th birth anniversary, Bombay named a road junction after him and Google featured a doodle showcasing a typical Bombay neighbourhood scene in the rains. In 2017, when Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa visited Goa, the country’s Medal of Cultural Merit was handed to Habiba (d. 2021). This year, Jazz Goa is due to celebrate ‘World Goa Day’ with Mário’s iconic cartoons coming to life in song.

Mário was a man of few words; but no words will suffice to describe his ‘glocal’ art. Luckily, his creations speak for him; they are amusing, magical, even therapeutic, so to say, and of perennial relevance. ‘Whether he has drawn priest, poet, or peasant, he has revealed the innate Goanness in each. Behind every creation of his there lies a hidden, mysterious, delicious, and sometimes malicious humour,’[89] writes Vamona Navelcar. And, of course, beyond the Goanness lies the humaneness of a man who thought locally, acted globally.

Mário is undoubtedly Miranda, the highly regarded one: ‘Your name from hence immortal life shall have.’ In addition to efforts put in by private institutions in Goa,[90] a permanent State-sponsored set-up[91] is important, to ensure that Mário lives into the next generation. Goa owes it to the man whose work, according to José Pereira, is ‘the most accomplished interpretation yet’[92] of the Goan ethos. His was a popular and powerful presentation to a global audience. Many still travel from far and wide in quest of Mário’s Goa; all being well, they will always find both Mário and Goa!

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[88] As told by Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 22.5.2021.

[89] ‘The Flowering of Goan Art’, by Vamona Ananta Sinai Navelcar, in Goa: Aparanta – Land Beyond the End, ed. Victor Rangel-Ribeiro (Vasco da Gama: Goa Publications Pvt Ltd, 2008), p. 126.

[90] Private initiatives by Mário Gallery, Azulejos de Goa, Velha Goa and Sunaparanta Centre for the Arts.

[91] Note the fiasco at Reis Magos Gallery, cf. https://www.heraldgoa.in/Cafe/Brushing-aside-Mario-Miranda%E2%80%99s-works-at-Reis-Magos-Fort/123554 Retrieved on 22 Aug 2021

[92] ‘Foreword’, by José Pereira, in Goa with Love (Goa: Goa Tours, 1982), p. 4.

Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 5/6)

January 28, 2022Moda Goa,Lady Hamlyn Trust,Victor Hugo Gomes,Reis Magos Fort,Trikaal,Mario's book illustrations,Mário and the Goan Cause,Wendell Rodrigues,Museum of Christian Art,Gerard da Cunha,Ranjit Hoskote,INTACH,Shyam BenegalBiography

Reinventing himself

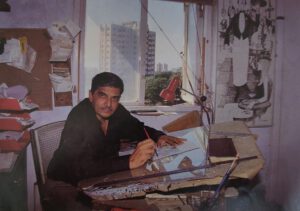

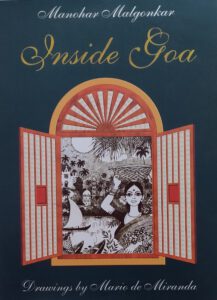

By his fiftieth year, Mário had developed an abiding interest in illustrating books. After Ruskin Bond’s The Room on the Roof, Uma Anand’s books for children,[69] and several business publications; Dom Moraes’ The Open Eyes: a Journey through Karnataka and A Family in Goa (1976); Manohar Malgonkar’s Inside Goa (1983), Lambert Mascarenhas’ In the Womb of Saudade (1994) and Mário Cabral e Sá’s Legends of Goa (1998) confirmed him in the art of book illustration.

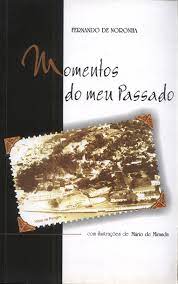

Now practically at the end of his career, doing illustrations for a book in Portuguese – Momentos do meu Passado (2002), by Fernando de Noronha – ‘brought back nostalgic memories of my youth spent in Goa,’ Mário said.[70] Victor Rangel-Ribeiro for his part recalls that when he proposed to the publishers that Mário be the illustrator for Loving Ayesha (2003), ‘first they said he would never agree; and when he agreed, they said he would be late with the drawings. He surprised us all by delivering the drawings on schedule.’[71]

Interestingly, Goa-based projects marked the beginning of Mário’s homeward journey. In 1979, the movie buff of yesteryear acted as a creative assistant for Sea Wolves, a war film shot in Goa. In 1985, Shyam Benegal’s film Trikaal based itself on snippets of the Miranda family history; it was shot in their heritage home and village, the film director deeply appreciative of India’s Latin character available only on its west coast.[72] The mansion, refurbished for the occasion, soon began to figure in coffee table books and glossy magazines.

Mário is possibly India’s only cartoonist whose sketches have been turned into murals. His first one came up in 1986, at Hotel Mayfair, in a quaint corner of Panjim. The next two locales were at Colaba: Café Mondegar, his favourite haunt, and Hotel Paradise.[73] Mário also honoured Goa’s Krishnadas Shama Library[74], Panjim’s municipal market complex,[75] and other locations in the country with his murals. The adaptation of Mário’s characters by Air India and by the Charles Correa-designed Kala Academy in Goa was yet another feather in his cap.[76]

In 1996, the Mirandas gave up their rented place at 7A, Oyster Apartments, Navy Colony, Colaba, and returned with their dogs, turtles, parrot and all to the same sleepy little village of Loutulim that was frozen in time almost just as Mário had left it half a century earlier. The homecoming far from ended his love story with Bombay, though; he continued infusing The Afternoon and The Economic Times with his brand of humour. And in the evening of his life the inveterate cartoonist was a welcome presence in Goa’s social and cultural circles as well.

The Goan Cause

Life had come full circle for Mário. ‘What I enjoy most is doing nothing, if I could… – back to the sossegado times!’ he said.[77] Yet he was always brimming with ideas; and even if a wee bit mystified by Goa’s half-hearted response to his work,[78] or so he thought, the quintessential Goan gentleman had many dreams to fulfil and promises to keep.

‘Goa has a different atmosphere from the rest of India. After all, Goa was with the Portuguese for 500 years…,’[79] said Mário. He planned to do a series of drawings ‘on my Goa, the Goa that I grew in, the past; the Goa which lots of people did not know existed.’ Considering it critically endangered, he wished to preserve it in his own way.[80] ‘Today, Goa is part of India, so naturally we will lose a lot and gain a lot,’ he said, hoping at the same time that ‘some of the heritage of the past remains and gives Goa this identity that I think it needs.’[81] According to art critic Ranjit Hoskote, Mário’s confluential, Indic and Iberian heritage, ‘gives him an amplitude of cultural references [and] a historically informed sensibility.’[82]

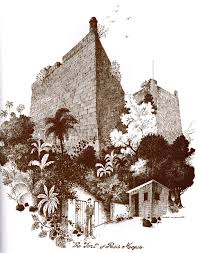

As the convenor of the Goa chapter of INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage), Mário was instrumental in getting the Gulbenkian Foundation to sponsor the establishment of a Museum of Christian Art at the Seminary of Rachol. He also secured funding from Lady Hamlyn Trust, London, for the restoration of the iconic Reis Magos Fort.[83] And even though daunted by politics and red tape, he lent his expertise to public institutions like Goa University, Kala Academy and Goa International Centre.[84] It is ironic that the consummate Goan artist who could make light of just any situation found little reason to smile when it came to the State handling of tourism, environment, animal welfare and heritage issues.[85]

Meanwhile, Mário encouraged fashion designer Wendell Rodricks to document the Goan costume, through the Moda Goa project;[86] and artist Victor Hugo Gomes to study Goa’s ethnography,[87] an experiment that led to the creation of the Goa Chitra Museum. As regards his own oeuvre, Mário was fortunate to see part of it documented in a large-sized book titled Mário de Miranda as well as displayed at Mário Gallery, by architect Gerard da Cunha.

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[69] The Room on the Roof was first serialised in the Weekly, in 1956; and Anand’s Dul-Dul, The Magic Clay Horse, The Adventures of Pilla the Pup, and Lumbdoom, The Long-Tailed Langoor) were published in the 1960s. Mário also worked on films for children, sometimes for free, Cf. Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op .cit.

[70] Mário’s statement to my father. Cf. Fernando de Noronha, op. cit.

[71] Email of 25.6.2021.

[72] Telephone conversation on 2.7.2021.

[73] https://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/art/his-drawings-had-a-special-quality-rk-laxman/article2707166.ece Retrieved on 8 August 2021. Mário chose not to sign the mural, possibly because the artwork was put together by students of J.J. College. Others were done by one Shetty, cf. Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[74] Façade mural and interior panels: project executed by Orlando de Noronha’s firm Azulejos de Goa, Panjim, in 2011.

[75] Executed by Panjim-based Rajesh Salgaonkar, 2005.

[76] Some undertaken by Deepak from Meerut, cf. Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[77] ‘Tale of Two Goans’, op. cit.

[78] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[79] ‘Tale of Two Goans’, op. cit.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Ranjit Hoskote, ‘The Art of Mario Miranda’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 81.

[83] In both projects he had the support of Bal Mundkur; Bartand Singh and Smith Baig of INTACH.

[84] Mário was declared Goa Today’s Man of the Year. Cf. interview with Alexandre M. Barbosa and Alister Miranda, in Goa Today, December 1998, pp. 18-23.

[85] Doordarshan National, Eminent Cartoonists of India, #04, op. cit.; Goa Today, ibid.

[86] https://www.firstpost.com/india/moda-goa-designer-wendell-rodricks-on-indias-first-costume-museum-and-his-vision-for-its-future-5510481.html Retrieved on 19 Aug 2021

[87] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/goa/dont-call-me-sir-call-me-mario/articleshow/11456423.cms Retrieved on 19 Aug 2021

Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 4/6)

January 27, 2022Nissim Ezekiel,Busybee,Laugh It Off,Midday,The Afternoon Despatch & Courier,Vinod Mehta,Mário's travels,Behram Contractor,A Little World of Humour,Fundação Oriente,Goa and Other WorksBiography

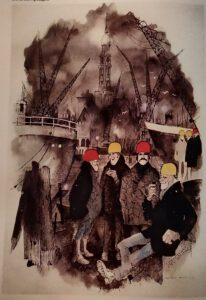

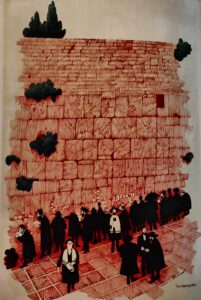

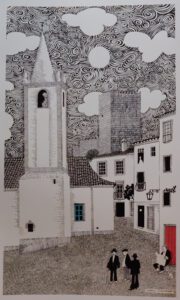

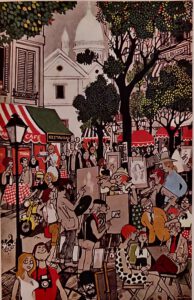

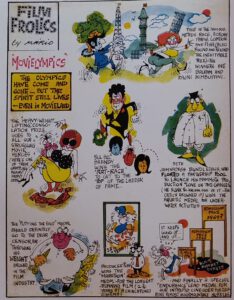

(L-R Dockworkers in Germany; Charley's Corner, NY; the Wailing Wall; a street in Portugal; open-air cafe in Paris)

Compulsive Traveller

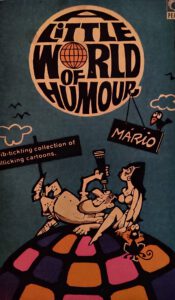

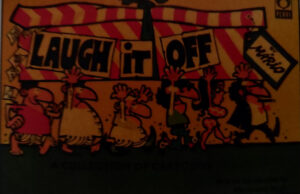

Mário was a persistent seeker of the funny side of life, as A Little World of Humour (1968) and Laugh It Off (1975) make it amply clear. He was never bored, even if stuck at an airport or a railway station; ‘watching people is an experience,’[53] he said. Bombay’s hustle and bustle had brought him face to face with crowds all right, but he only loved watching them, not being in them![54] He enjoyed walking around, be it in the village or the city; to him, walks were ‘life’s mini-journeys that could be turned into a movie’, says Rishaad.[55]

Mário was a persistent seeker of the funny side of life, as A Little World of Humour (1968) and Laugh It Off (1975) make it amply clear. He was never bored, even if stuck at an airport or a railway station; ‘watching people is an experience,’[53] he said. Bombay’s hustle and bustle had brought him face to face with crowds all right, but he only loved watching them, not being in them![54] He enjoyed walking around, be it in the village or the city; to him, walks were ‘life’s mini-journeys that could be turned into a movie’, says Rishaad.[55]

Mário drew from observation, from life, prompting Nissim Ezekiel to remark: ‘No escape if Mario is looking at you.’[56] In his illustrations always teeming with human specimens, each had their own story to tell. However, sometime later, began cherishing moments away from the madding crowd, say, by slipping into the anonymity of a movie hall.[57] Was it plain overload or a midlife crisis that had suddenly brought on the feeling that ‘life is not funny as all that’[58]?

Fortunately, there was an upside to the behaviour change. Mário got less and less interested in cartooning and more and more excited about capturing moods and ambiences for his pictorial travelogues.[59] He made no bones about his travel mania – ‘especially if someone else is footing the bill!’ as he would say in jest.[60]

In 1979, a year after a major trip to Germany, he quit the influential Times Group and joined a fledgling tabloid, Midday, under Contractor’s editorship. From 1985 onwards, he was a freelancer with the same editor’s The Afternoon Despatch & Courier: not only did his cartoons gel with Busybee’s humour, the paper’s relaxed pace permitted him and wife to travel and draw at will. Sometimes, Habiba and the sons joined him on cross-country jaunts, which were truly memorable, says Raul.

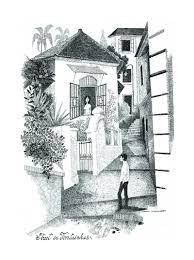

Mário’s wanderlust brought forth the sublime artistry of his pencil and brush, ink and paper – fascinating enough to fill a book. Generally, after he had spotted his themes, his pen would scribble just a few hasty lines, later turning them into finely detailed and nuanced sketches, thanks to the artist’s photographic memory for faces and buildings[61] (he especially loved old people and ruins). Mário’s traditional line art had by now got stylised into neat, black ink pen illustrations, sporting straight graphite lines with flat cross-hatching for tonal variations.[62] Mário said, ‘If you see my early work and compare it, you’ll see I always enjoy experimenting.’[63]

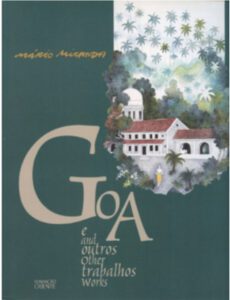

Over a span of three decades, Mário put up more than thirty solo exhibitions across the country[64] and the world.[65] Vinod Mehta saw no contemporary illustrator or cartoonist in India coming close to Mário’s command over the grammar of drawing; the alleged ‘lack of venom’ in his repertoire spoke for his ‘objective perspective’.[66] In the year 2000, Fundação Oriente in collaboration with the Indian Council for Cultural Relations organised a Mário retrospective titled Goa and Other Works[67], honouring the man who for years had served as a cultural link between Portugal and India (Figure 4).[68]

Over a span of three decades, Mário put up more than thirty solo exhibitions across the country[64] and the world.[65] Vinod Mehta saw no contemporary illustrator or cartoonist in India coming close to Mário’s command over the grammar of drawing; the alleged ‘lack of venom’ in his repertoire spoke for his ‘objective perspective’.[66] In the year 2000, Fundação Oriente in collaboration with the Indian Council for Cultural Relations organised a Mário retrospective titled Goa and Other Works[67], honouring the man who for years had served as a cultural link between Portugal and India (Figure 4).[68]

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[53] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[54] ‘The Last Interview’, op. cit.

[55] Personal interview, 9.7.2021.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Pritish Nandy, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/mario-miranda-the-man-who-made-miss-fonseca-famous/articleshow/11075146.cms

[58] Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 3 (Outtakes), 26.6.1991, op. cit.

[59] Germany in Wintertime (1980); Impressions of Paris (1985); Desenhos e Aguarelas (1987); Spain (2007), et al.

[60] ‘Tale of Two Goans’, op. cit.

[61] ‘The Last Interview’, op. cit.; for Mário sketching in loco, cf. Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 1 (Outtakes), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UBTrDEU9gEQ

[62] ‘The Last Interview’, op. cit.; for Mário at work in Bassein cf. Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit..

[63] ‘Tale of Two Goans’, op. cit.

[64] His first countrywide tour, ‘American Sketchbook’ (1975), included Panjim, Calcutta, Madras and New Delhi.

[65] In Paris, New York, Lisbon, East Berlin, Singapore, Muscat, Jerusalem and Macau, among others.

[66] Vinod Mehta, ‘Tomorrow is another day’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 140.

[67] [Lisboa]: Fundação Oriente, 2000.

[68] Mário was the local coordinator of Fadista Amália Rodrigues’ visit to Goa, in 1990, sponsored by Fundação Oriente, as a prelude to setting up office in Goa. Also cf. ‘From Lisbon with Love’, by Mário, in Goa Today, February 2001, pp. 18-19, describing his exhibition and stay in Portugal in the year 2000.

Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 3/6)

January 25, 2022R. K. Laxman,Victor Rangel-Ribeiro,Behram Contractor,Indian Institute of Cartoonists,Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian,Bal Mundkur,Rishaad de Miranda,Lilliput,Gerson da Cunha,Habiba Hydari,Mário's cartoon characters,Dom Moraes,Mário in Portugal,Bachi Karkaria,Mário and US cartoonists,Busybee,Bangalore,The Times of India,Alyque Padamsee,Raul de Miranda,Punch,Ronald Giles,Frank Simões,Jean de Lemos,United States Information Service,Alexyz,Nissim Ezekiel,Cocktail,Mário and Israeli cartoonists,Vinod Mehta,Mário and British cartoonistsBiography

Welcome Break

Mário’s diaries were sacrificed on the altar of newspaper cartooning. In 1959, the caricaturist flew to Lisbon on a Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian scholarship.[28] He toured the length and breadth of Portugal, distilling the essence of the Portuguese soul into his sketches and drawings. The experience brought a fresh perspective to his profession:[29] it whetted his appetite for travel and charted a path that would reveal itself with time.

It is unlikely that Mário would go out of his way to confer with the Portuguese cartoonists reeling under an authoritarian regime at the time. In London, later that year, he met with Ronald Giles, Raymond Jackson (Jak), Victor Weisz (Vicky), and memorably bumped into his all-time favourite Ronald Searle at a pub on Fleet Street! He was happy to do cartoons for the classic humour magazine Lilliput and for ITV, but featuring in Punch, the flag-bearer of humour magazines, really was the icing on the cake.

Mário’s passage to England was a turning point in his career. He earned money and friends; more importantly, Searle’s injunction – ‘Stay on in England, but stop copying me!’[30] – infused him with the confidence to go it alone. But then again, the dramatic regime change in Goa, on 19 December 1961, made him turn on his heels. He returned to Bombay on an Indian passport and rejoined the Times Group; but this time around, R. K. Laxman, the reigning deity of The Times of India, ‘subtly ensured that the pedestal was not for sharing,’ says journalist Bachi Karkaria.[31]

Appreciating the steady stream of cartoons that Mário had sent home while on his working holiday abroad, Bombay’s Cocktail magazine commented: ‘Mario is so well known that it’s difficult to say things about him that will not be superfluous. A man who can draw and depict the funniest in the most convincing manner, his Shammu has won the laughing interest of everyone. Every cartoon of his is a refreshing experience. He lampoons the frailties, foibles and social shortcomings of us all. His hilarious work is packed with characters from the contemporary scene and his greatest gift is that he makes us laugh at ourselves. His illustrations too have polished perfection and have been such a success that all our writers want Mario to illustrate their work.’[32]

In Mário’s absence, Jean de Lemos, an artist born in the Nilgiri heights, handled the bulk of illustration; they had a soft spot for each other and even exchanged sketches (Figure 3).[33] On his return, though, Jean learnt that Mário was getting engaged to Habiba Hydari,[34 a 24-year-old fine arts student-turned-air hostess whose ‘teenage gang’ had once been part of his circle.[35] Jean exited, but remained friends with Mário’s family.

On 10 November 1963, Mário and Habiba[36] got married in a civil ceremony, and set up home at Rockville. Their children, Raul,[37] a hairstylist, and Rishaad,[38] a designer-decorator, who live in Loutulim, remember their mother as ‘the boss’ and their father as a calm, liberal, and generous man.[39] Mário for his part rued the fact that he was usually too absorbed in his work to resolve pressing domestic issues with a firm hand.[40]

Versatile Artist

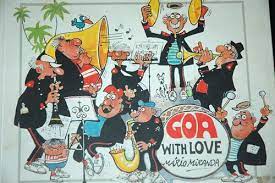

In 1964, Mário brought out a book of sketches, Goa with Love,[41] dedicating it to Habiba. His visibility was on the rise – in school textbooks, corporate calendars, advertisements and trendy magazines. Successive editors of the Weekly[42] held Mário in high esteem; and humourist Behram Contractor (alias Busybee), political commentator Vinod Mehta, poets Dom Moraes and Nissim Ezekiel, and admen Gerson da Cunha, Frank Simões, Bal Mundkur and Alyque Padamsee were among his closest friends. They churned out reams of prose and loads of ad copy; Mário read between the lines and came up with charming visuals.

Mário’s reading, now restricted to periodicals, stood him in good stead.[43] Victor Rangel-Ribeiro believes that the cartoonist’s stays overseas, ‘particularly the long months he spent in London, plus the fact that he was very well read in Portuguese as well as English literature, did give him a broader outlook than one normally found in members of the local press.’[44] But Mário wore none of that on his sleeve; in fact, he abhorred ‘intellectual talk’, his forte being ‘the accumulation of trivia judiciously and harmoniously composed,’[45] as Vinod Mehta puts it.

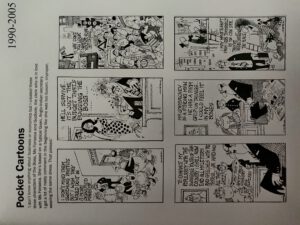

That is evident from Mário’s daily cartoon strips, some of which drew upon people he met in daily life: the archetypal secretary, Miss Fonseca; the Boss and his hapless minion Godbole; the fat, corrupt politician Bundaldass with his sidekick Moonswamy, and the bosomy Bollywood star Rajani Nimbupani.[46] Millions across generations grew up on those cartoon characters that were all the rage; they are now etched in the collective memory, even if the world’s ever-changing sensibilities tend to put a negative spin on some of them.[47]

Nineteen seventy-two was a landmark year: the United States Information Service (USIS) flew Mário to America, and Tel Aviv invited him to stop en route. He met Israeli cartoonists Kariel Gardosh, Shemuel Katz and Friedel Stern; and in the US he interacted with Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts; Herblock, editorial cartoonist of the Washington Post, Pat Oliphant of the Denver Post, Ed Fisher of The New Yorker and freelancer Al Jaffee. Mad magazine featured him, and back home Mário wrote a piece titled ‘Cartoons – American Style’[48] – a pointer to his writing talent[49] lost in the rough-and-tumble of editorial cartooning.

As India was beginning to see him in a new light, Mário lamented the tendency to seek validation from agencies abroad[50] and wept over his countrymen’s inability to laugh at themselves. He regularly discussed the state of the profession and, Alexyz recalls, he encouraged budding cartoonists. He inspired the formation of the Indian Institute of Cartoonists, Bangalore, and gifted them many of his priceless originals.[51]

Mário was among the handful of cartoonists[52] that ruled the roost in India, but alas, long years of caricature art had left him with little leisure to pursue what he liked best: sketching. The reprinting of Goa with Love in 1982 was thus as much a celebration of the fast-fading world of his youth as it was an evocation of the line art that had grown on him.

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[28] The scholarship possibly came as a result of Maria Zulema’s letter to Minister Pedro Teotónio Pereiras. Mário lived in a rented room on Rua Actor Isidoro. (Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.6.2021)

[29] Published in Diário Popular, cf. ‘M de Mário’, by Jorge Silva, in Macau, April 1993, II Series, No. 12, pp. 39-43.

[30] ‘The Last Interview’, op. cit.; FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.; ‘Tale of Two Goans’, op. cit.

[31] https://indianjournalismreview.com/2011/12/12/did-r-k-laxman-subtly-stifle-marios-growth/ Retrieved on 8 August 2021.

[32] Cocktail, January 1960, p. 5.

[33] Mário called her Chips; she called him Popat (Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021)

[34] Daughter of Iqbal Hydari, a senior executive of the Indian Railways and scion of the nobility of Hyderabad, and Rohaina Mohamedi, a painter.

[35] Mário’s circle included Lúcio Miranda, a third cousin, and Sarto Almeida, both architects. Cf. Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 17.

[36] He called her ‘Charlie’, and she called him ‘Joseph’.

[37] Married Magen Gilmore, who lives in the US with their daughter Gayle Zulema.

[38] Married to Sabine Frank, who lives with their children, Rafael and Samuel, in Austria.

[39] Personal interview on 9.7.2021.

[40] As told by Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021.

[41] There are at least three known editions of Goa with Love (1964, Times of India, Bombay; 1982, Goa Tours, Panjim; 2001, by M&M Publications, Reis Magos). In 1964, Mário also brought out ‘Goa Postcards’.

42] Khushwant Singh, M. V. Kamath and Pritish Nandy were the last three editors of the Weekly.

[43] All India Radio, Bengaluru, interviewed by Shylaja Gangooly, 27 Nov 1993. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kDDO3N4OVtA

[44] Email of 10.7.2021

[45] Vinod Mehta, ‘Tomorrow is another day’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 139.

[46] Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[47] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/sunday-times/kerala-to-us-cartooning-is-in-the-crosshairs/articleshow/69805457.cms Retrieved on 22 Aug 2021

[48] The Illustrated Weekly of India, 2 January 1974.

[49] Mário liked to write (B. Contractor and K. Singh encouraged him) but found it ‘a slow and irritating process’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zJB0u-_akA

[50] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[51] https://www.deccanherald.com/content/211335/cartoon-gallery-gets-mirandas-priceless.html

[52] K. Shankar Pillai, R. K. Laxman, O. V. Vijayan, Abu Abraham, Rajinder Puri, E. P. Unny.

Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 2/6)

January 25, 2022The Current,Loutulenses League,Goa Medical Ball,Momentos do meu Passado,Morarji Desai,Walter Langhammer,Policarpo Vaz,The Illustrated Weekly of India,Gerard da Cunha,D. F. Karaka,Dom José da Costa Nunes,Fernando de Noronha,C. R. Mandy,Polly VazBiography

The Artist as a Young Man

The Artist as a Young Man

It was during his college days in Bombay that Mário’s characters first strutted out of his diaries; he drew pocket cartoons and peddled them at Flora Fountain for pin money.[11] And at a medical ball held at Clube Vasco da Gama, Panjim, couples dancing the night away delighted in the frisky sketches of the faculty members that Mário kept drawing on the wall mirrors lining the ballroom.[12]

It is not that Mário always passed uncensured. One day, a priest from the village, whom he had depicted outside the local fish market, showed up at his house. Mário’s mother, after doing her best to placate the visitor, ended up going to see archbishop Dom José da Costa Nunes, who had once expressed his wish to meet the young artist. Mário was hesitant but once there, was relieved to see his diaries spark guffaws rather than a controversy. ‘That was the first time I was appreciated by someone I didn’t know,’ he said.[13]

Mário maintained a diary right through his years spent in British India with intermittent stays in Goa and Damão (Figure 2). The last three logbooks (1949-51),[14] now available in print, are a shrine of frolicky pictures of relatives and friends in Loutulim, Panjim and Margão.[15] To quote Nissim Ezekiel, ‘the buffoonery of his human figures is redeemed from grossness by their verve, their inner urge towards going places, getting somewhere. It is not always their fault that there is no place to go, nowhere to get except through the corridors of illusion.’[16]

That was Mário’s equivalent of the dark night of the soul! His lifestyle was a cause of concern to his by now widowed mother struggling to manage the household while at the same time providing for Pedro at Princeton University.[17] But then Mário had a change of heart: was it the showcasing of his watercolours and drawings by the 1950 Souvenir of the Bombay-based Loutulenses League[18] that did the trick?

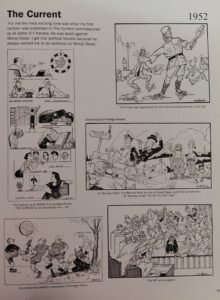

In 1951, seeing a bleak future for himself in Goa, Mário moved to Bombay. Though creative possibilities seemed unlimited here, he was jobless and quite badly off at first. That’s precisely when Policarpo (Polly) Vaz, a fellow hosteller at Rockville,[19] famously suggested to him to hand-craft picture postcards depicting the city monuments, offering to sell them at the hotel where he worked the night shift. Needless to say, the two became fast friends; and they had even thought of migrating to Brazil,[20] when Mário got a call from D. F. Karaka of The Current. The redoubtable editor, riveted by Mário’s diaries, commissioned him to cover a can-can dance scene at the Taj Hotel, and received such a rib-tickler that he promptly took him on as the tabloid’s regular cartoonist.

The young Goan created a stir in Bombay's journalistic circles when his cartoons first appeared in the press. Editor C. R. Mandy and art director Walter Langhammer soon invited him to The Illustrated Weekly of India. Before long, other Times Group publications,[21] too, began to use Mário’s drawings; they skilfully portrayed movement and sound, and often featured the cartoonist’s trademark dog.

Art of Cartooning

That was the year 1952. Mário had virtually stumbled into the profession of cartooning.[22] To an onlooker the job seemed easy, and everything grist to the mill – from the bureaucracy, fashions, business, and people’s habits, to the animal world, environment, music, society, and even politics – but really, finding humour was no mean task. ‘There are times when you don’t feel funny, or may not feel like laughing, but still have to produce a funny cartoon – like a clown who has got to make people laugh all the time, although he doesn’t feel like laughing.’[23]

Elaborating on his predicament, Mário said, ‘People expect me to come up with jokes and anecdotes to make others laugh. I can’t do that. I enjoy humour if it comes from someone else who knows how to tell a good joke…. I am not a naturally funny person; I may look funny, but I am not funny.’[24] And if a cartoonist’s defining quality it is ‘to detect funniness in people’s behaviour or physical features and draw it, it is equally important to be able to laugh with someone, not at someone, without being cruel,’ said Mário, adding: ‘Humour is something very personal, individual. What’s funny to me may not be funny to you. Sometimes I do something which I think is very funny – and it flops! And people asking you to explain a cartoon flattens it completely.’[25]

Past the initial scramble for work, Mário began to yearn for the blissful spontaneity of his diary sketching. Add to this the fact that political bigwigs were breathing down his neck, and Mário had a sure recipe for disenchantment. Bombay Presidency’s Home Minister Morarji Desai was among the first ones to let his irritation show – something that taught Mário early on that lampooning political animals involved high risk. When he toned down the humour to appease the readers, cartooning quite paradoxically became a ‘serious business’. ‘Cartoonists are very serious people, and cartoons, no laughing matter,’[26] he quipped.

Finally, Mário stopped pursuing individual politicians; he began to see himself as a social caricaturist more than anything else. He is on record as saying, ‘I am not even a cartoonist; I draw… give me a pen and blank paper and I will draw. I just love to draw.’[27]

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[11] ‘Tale of Two Goans: Mario Miranda & Wendell Rodricks’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5FDLGApfATc&t=5s

[12] Cf. Fernando de Noronha, Momentos do meu passado (Goa: Third Millennium, 2002), p. 146.

[13] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[14] Cf. The Life of Mário (1949, 1950, 1951) ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous), in 2016, 2012 and 2011, respectively. Fátima Miranda Figueiredo reckons that her brother’s diary sketches total up to about 6,750 over a period of 18 years (1934-1951).

[15] He frequented the houses of his relatives, Judge António Miranda and Captain Adolfo Menezes, in Panjim, and Judge Eurico Santana da Silva, in Margão; and often stayed overnight with friends in their hostels.

[16] Nissim Ezekiel, ‘No escape if Mario is looking at you,’ in Mário de Miranda, ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous, 2005), p. 276.

[17] As told by Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021.

[18] Souvenir of the Silver Jubilee of the Loutulenses League (Goa: Imprensa Nacional do Estado da Índia, 1950). Curiously, in the chapter titled ‘The Rising Generation’, Mário figures as an Arts graduate, not as an Artist.

[19] Polly was from Bastorá; other hostelites, Joe Albuquerque and Paulo Miranda, from Loutulim. Cf. Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 14.

[20] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 15.

[21] Femina; Filmfare; The Evening News and The Economic Times.

[22] Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[23] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 24; Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.