Fatima, alive and tender

Today is the 104th anniversary of the Apparitions of Our Lady of Fátima. It is also the 75th anniversary of the crowning of the Statue and the 40th anniversary of the attempt on the life of Pope John Paul II at St Peter’s Square.

In the words of the Rector, while the silver and gold of that crown represent the joys of life, the bullet fitted therein represents our life’s sorrows.

The four-hour ceremony on this rainy morning at Fátima began with a multilingual recitation of the Holy Rosary and ended with Holy Mass presided over by Cardinal José Tolentino de Mendonça.

It was a touching testimony of love from pilgrims (number restricted to 7500, in keeping with covid-related SOPs) to their Mother, Queen of Heaven and Earth, who is always alive and tender.

Novos temas, novos rumos

May 11, 2021Maureen Alvares,Goa,Sheela Kolambkar,Revista da Casa de GoaGoan Culture

Editorial

Como que num piscar de olhos chegámos ao 10.º número da nossa querida Revista. Queira Deus que a possamos acompanhar durante o tempo que for necessário. Não é só um projecto gratificante; é um trabalho importante – dir-se-ia, premente – nos tempos conturbados em que vivemos. Por isso, vivat, crescat et floreat são os nossos votos.

Nunca foi tão urgente, como o é agora, recuperar o passado para o bem do tempo presente e garantia do futuro. Na verdade, está em jogo a vivência goesa, esse modo de estar tipicamente indo-português. Infelizmente, com a velocidade estonteante em que gira o nosso mundo pessoal e colectivo, pouco tempo nos resta para reflexão, para não falar de acção. Por isso, importa que a nossa agenda seja a de reunir o pessoal e pôr mãos à obra.

O acto de reunir os Goeses dispersos pelo Mundo nunca superou, na nossa Revista, aquilo que presenciamos na presente edição, que tem colaboradores das diásporas luso e anglo-goesas. Temos de tudo: uma lenda de Goa pré-cristã e animista, tal qual narra Celina Velho e Almeida, residente em Goa, até à história duma intriga, pouco conhecida, que se passou em Goa, na época da Segunda Grande Guerra, a qual é contada pelo novo colunista, Armand Rodrigues, que vive no Canadá.

Também pouco conhecida da geração moderna é a história da grande aventura que foi a primeira travessia aérea Lisboa-Goa, relatada aqui com pormenor pelo goês lisboeta Francisco Monteiro. De igual modo, o casal Philomena e Gilbert Lawrence, nossos novos colaboradores, de Nova Iorque, dão uma vista panorâmica da secular ligação entre o povo goês e a Grã-Bretanha, que começou com a breve ocupação de Goa pela tropa inglesa, no fim do século XVIII, e continuou com o recrutamento comercial de goeses por aquele país.

Os nossos leitores irão também deliciar-se com três micro-histórias de Goa, não de somenos importância: José Venâncio Machado, radicado em Portugal, lembra-se com emoção das 153 missas celebradas simultaneamente no largo que estadeia entre a Sé e a Basílica, na Velha Cidade de Goa; Ralph de Sousa relata com verve o vaivém silencioso e apressado de gentes nos transportes fluviais de Goa; e Francisco Monteiro retrata a figura de Paulino Dias, uma das maiores figuras da literatura indo-portuguesa, a quem apelida de “poeta da mitologia hindu”.

Ainda no campo literário, temos Sheela Kolambkar, escritora goesa da língua concani, hoje estabelecida em Bombaim, cujo conto, além de transliterado em caracteres romanos, é também traduzido em português pelo signatário destas linhas; e, mais além, Maureen Álvares, numa entrevista comigo, fala do estado actual da língua e cultura portuguesa no território goês.

Para terminar, no contexto da notícia do lançamento do livro Nacionalidade e Estrangeiros, de Edgar Valles, e a crítica feita por José Filipe Monteiro ao livro Entre dois impérios, de Filipa Lowndes Vicente, volto a realçar que nesta edição da nossa Revista vemos ampliada a nossa visão do Goês como verdadeiro cidadão do Mundo.

Como pano de amostra da nova vitalidade que nos brinda enquanto chegamos à bonita idade de dez edições temos a parceria entre a nossa Revista e The Global Goan, sediada na Oceania. Na verdade, “se mais um mundo houvera, lá chegara”.

É claro que, ao fim e ao cabo, o importante não é chegar algures mas, sim, fazer algo de bom e belo. Eis a Revista da Casa de Goa, a menina dos nossos olhos, que tem o condão de produzir novos temas e novos rumos. Mas não paremos por aí. Olhemos atentamente para os gravíssimos problemas da actualidade goesa e sejamos o fulcro dum plano de acção conjunta da nossa comunidade espalhada pelo mundo, em prol da nossa sempre amada Goa.

(Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 10, Maio-Junho 2021)

Lenten Traditions in Goa

March 21, 2021Santos Passos,Fr Joe Rodrigues,Vatican Council II,Alcântara Barros,Fr Vasco do Rego,Lenten Procession at Goa Velha,Manuel Morais,Fr. Lino de Sá,Fr Romeo Monteiro,Fr Santana Faleiro,Mandó,Motetes,Raimundo Barreto,Fr. Lourdino Barreto,Varela Caiado,Fr. Bernardo CotaInterview,Lenten Traditions

ON: What do you have to say about Goa's rich tradition of Lenten music?

JLP: Well, the Motetes (Motets) are Goa’s “classical” Lenten music. They began appearing by the middle of the 19th century. They were sung on the occasion of the Santos Passos (Holy Steps of the Cross) and also during the Sacred Triduum, that is, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday. This is Goan Lenten music par excellence. Enter Vatican II in the 1960s and as a result we now have many Lenten hymns – liturgical songs to be sung in church – all composed in the Konkani language, beginning from the year 1965.

ON: What might the earlier Lenten music have been, before the Motets came about in the middle of the 19th century?

JLP: I have no idea. They must have been only hymns in Latin because the liturgy was in Latin. The Parish Schools, for example, began in Goa way back in the 16th century. No Konkani music or hymns were taught there. It was only Latin. The students of our parish schools learnt even choral songs. They could sing in polyphony and they sang serious classical music, like Palestrina and later Perosi and others.

ON: The church Mestres (music teachers) must have also contributed a lot…

JLP: Yes, the Mestres of our Churches, who were also music teachers in our parish schools, used to compose a lot of music in Latin, especially Masses. I am from Benaulim and I met one or two Mestres in my childhood – one was Sabino Rebello and the other was some Roque whose surname I forget, who was the Mestre of St John the Baptist Church, Benaulim.

ON: Are there any studies on the Motets and the religious music of Goa?

JLP: Yes, there are certain studies made on the Motets. To my knowledge, one by Fr. Lourdino Barreto and the other by a Portuguese musicologist, Prof. Manuel Morais. Fr. Romeo Monteiro has published a booklet on this.

ON: Come to think of it, the Motet and the Mando belong to the same period!

JLP: Exactly, the Motet and the Mando came up in the second half of the 19th century. It was perhaps the fruit of what we could call a “compositional spurt” among Goan composers. At least for some hundred years in Goa, motets were composed in Latin. Perhaps in the nineteen fifties or a little earlier, they began composing motets in Konkani, like “Vell Mhozo Paulo” …

ON: Who composed it?

JLP: Look, we have a curious fact here. Manuel Morais has already found a number of motets, both in Latin and in Konkani, but there is no name of the composer!

ON: What could the reason be?

JLP: What he says is that perhaps the composers were few and widely known and hence there was no interest in knowing who had composed them.

ON: Let’s say, the composer of “Sam Francisku Xaviera”…

JLP: Raimundo Barreto! He is widely known for his iconic composition “Sam Francisku Xaviera”. I don’t know of any other composition by him. He probably has some.

ON: Would there be a way of collecting all the motets?

JLP: Yes. There are bound to be other motets, in private collections. Perhaps these Mestres, no longer alive today, have left in their trunks some other motets that are not known; but I doubt we shall ever know the names of the composers. That will be very difficult to find.

ON: So, at least regarding motets, we have surprises awaiting us…

JLP: I think so too.

ON: Let’s hope so! And now, let’s talk about music composed after the Vatican Council…

JLP: There are a number of composers, starting with Fr. Vasco do Rego. He was the pioneer of liturgical music in Konkani here in this diocese. We had religious songs in Konkani, even Lenten songs, which were not motets, like “Deva doiall kakutichea”, “Jezu mhojea tujer hanv patietam”. They are penitential hymns which most probably are one or even two centuries old. But the post-Conciliar impetus was given by Fr. Vasco do Rego. He composed many Lenten hymns and he was followed by others.

ON: And who would the others be?

JLP: Fr. Bernardo Cota, Fr. Lino de Sá, Fr. Santana Faleiro, Fr. Joe Rodrigues (this one is a junior priest, but has a couple of compositions)…

ON: And there must have been lay people…

JLP: Yes, there were lay people, too, like Alcântara Barros … and there was one who had been the Mestre of Verna church: I don’t remember his name.

ON: And Varela Caiado?

JLP: Well, I know Varela Caiado as the organist of our Cathedral in Old Goa. I don’t know him as a composer. I have no idea of any compositions by him. But he was a first-rate musician. He was the organist of our Cathedral: this is all I know of him.

ON: Are there productions of Lenten music brought forth by the Diocesan Commission for Sacred Music?

JLP: Yes, there are. I think there are at least two publications of Lenten sheet music, some loose leaflets, besides one or two audio compact discs.

ON: What would be some peculiarities of the Lenten rituals in Goa?

JLP: Well, we have traditions in Goa that are not followed elsewhere. First, the Santos Passos procession is something typical of Goa, and perhaps of a few other parishes which were part of the Diocese of Goa in times gone by, like Belgaum, Sawantwadi, Karwar: these places, which now belong to other dioceses, were part of the Archdiocese of Goa; so the Santos Passos are to be found there too. If one goes to Central India or South India or North India, no, no Santos Passos there. We have inherited this from Portugal, where the tradition still exists.

Here in Goa, the Santos Passos are an interesting event…. There are ‘two Goas’: North Goa and South Goa. In North Goa, Santos Passos are celebrated on every Sunday of Lent. If on the first Sunday of Lent one dwells on the Condemnation of Christ, the second Sunday is the Ecce Homo, on the third Sunday we have the Lord carrying the Cross, on the fourth Sunday, the Lord meeting his Mother on the way to Calvary, and so on: each Sunday offers a meditation on one of the Passos or steps of the Way of the Cross. They are not the fourteen stations, but just a few of them.

In South Goa, it is only one Sunday. For example, in Benaulim, it is the fifth Sunday, in Loutulim it is the third Sunday, and so on. Here you have only one procession of the Santos Passos, incorporating one or two or three Passos of the Way of the Cross.

Another tradition in Goa, both in North and South Goa: a child sings a Veronica hymn… Earlier on, the songs were only in Latin, but now there are Veronica songs in Konkani too.

ON: And the Procession of the Franciscan Saints?

JLP: Well, the Procession of the Terceiros: this too comes from Portugal! Here in Goa we know them as Terciários. In Portugal they are known as Franciscanos Terceiros or Franciscans of the Third Order. I wouldn’t know in which part of Portugal, but they still hold this procession of the Franciscan Saints over there. Here the procession is held only in one place: Goa Velha.

ON: But I’ve heard that Rome is the only other place where such a procession is held…

JLP: I’ve heard that too. If it’s true, I wouldn’t be able to say in which parish of Rome it is held. But I can tell you that there are a couple of parishes in Portugal where such a procession of Franciscan Saints is held: fourteen, fifteen andores (litters) are taken in procession, just like in Goa. But here, no longer are they Franciscan saints alone. There are other saints: Saint Joseph Vaz, the Patron of our Archdiocese, has already been added to the saints here. Don’t be surprised if one day the procession adds in Mother Teresa, Saint Teresa of Kolkata….

ON: But how did a Lenten procession of Franciscan Saints come about in the taluka of Ilhas or Tiswaddi, which was evangelized by the Dominicans?

JLP: Well, this procession, which takes place on the Monday following the Fifth Sunday of Lent, began in the Pilar Monastery, at a time when the Franciscan Capuchos lived there. When the Monastery was shut down, all those saints or images were lodged at the Parish Church of Goa Velha… Note that Pilar still belongs to the parish of Goa Velha, and it is this same parish that holds the procession every year.

ON: As we come to the end of this chat, may I ask you for a message for the season of Lent!

JLP: My message as a priest is that we should live the spirit of Lent as it should be: a spirit of penance, saying no to ourselves, all right, but not with ashes on our heads or sitting on sackcloth as they did in the Old Testament. Ours is a more joyful Lent, because the penance I make, I make it with love and with joy: I am anticipating the joy of the Lord’s Resurrection!

For the original audiovisual version in Portuguese, see Renascença Goa at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXlnAoKU42M

English translation by the interviewee, at my request.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), Series II, Issue 9, March-April 2021 and here with a few additional inputs from the interviewee.

Nillu - 1

March 16, 2021Short Story,Transliteration

Sheela Kolambkar-hachi lhan kotha (poilo bhag).

Devanagarintlem Romi lipiantor korpi: Óscar de Noronha

Thodde lok zolmak ietnach almpeddearxe ietat. He lok astat jevnnak mar ani dhortorek bhar mhonnttat polle tosle…. Te kam’dhondo kãi korinat. Tori punn tanchem pott bhorta. Bekar asa mhunn khobor astana tachem logn zata. Tankam bhurgim zatat. Bhurgim xiktat, vhodd zatat. Oxem toren dixtt lagsarko tancho sonvsarui bin zata. Ek poiso zoddi nastanam. Koso to Devakuch khobor! Zonn eke chonchik Devan chorov ghotto dil’lo asta khoim! Toslo to chorov, kãi hat-pãi haloi nastana jea lokamchea thonddant apxinch poddta te lok kitle sukhi! Ani thoddo lok mormorsor kam’ kortat, punn tea lokank dhod ek jevonn susegad bosun jevonk mellna. Kortele kitem? Kormacheo goti ani muien gil’lo khoim hoti, tosleantli khobor!

Toslea almpeddear monxam bhitorlo ek monis mhollear Nillu. Horxim tagelem nanv Nilkant punn Gõykarache nanvanchi vidornam korche sonvoiek lagun to zalo Nillu. Ani Nillu-le avoi-bapui gorib axil’lean soglle taka Nilluch mhonnunk lagle. Zantte-nentte, soglleancho to Nillu axil’lo. Nillu zor ekadrea bhattkarager zolmak ail’lo zalear Nillubab zatlo axil’lo. Ghoddie to Portugez xikil’lo ani khõiui empregad bin axil’lo zalearui to Nillubab zavpacho. Punn to zalo almpeddear ani Nillu to Nilluch ul’lo.

Nillu chear choliamvelo cholo. Mhunn avoi-bapailo khub’ apurbaiecho. Tagelea avoi-bapaili goribkaiechi poristiti asun legit tannim taka laddan vaddoilo. Soglleank ukddea tanddlachem xit ani ho apurbaiecho ekloch put mhunn haka barik tanddlachem xit. Avoi-bapain kel’li tachi sovõi il’li legit vochunk nam. Tachi bail taka barik tandllachem xit tache purtench korun vaddtali.

Nillu nanvapramann nilloch. Mhollear kallokitt. Ghos koso. Tangelem kens legit thondda mukhar matxe dhove distale, hache velean polloiat. Taddmadd koso lambuch lamb. Angan dhondio naslo tori barikui bin nhoi. Niktto valo nesoun ani hatant dhanddo diun, kor’kor’avazacheo vhanno ghalun taka khõicheai sanvari ponda ubo kel’lo zalear lok taka devcharuch mhonttale axil’le. Thond chovkonni. Chovkonni chereacher il’lixi khaddki. Sokoilo vhontt dantani chabun chabun sodanch thambddo gunj zaun astalo. Nillulo vhontt jitlo chodd thambddo, titleo tachekodden hun’hunit gozali asat mhunn somzuchem. Soglleant sobit axil’le tagele dolle. Chokchokit toxe dhoveful. Tantunt sodanch bhurgeancho koso gollgollit nirmoll hanso. Dantui tagele dhoveful. Mogre kolle koxe. Eke vollsorent gunthil’le. Atam zantto zal’lean tagele kens sap dhove zaleat. Ani fottochi negative koso to dista.

Hanvem Nilluk lhan astana pollel’lo toso to asa. Tantunt il’loi forok nam. Fokot kes pikleat. Kes tache matxe lamb-chipchipit tel laun to te porte volloita. Kasatto marun nexil’lem, nill ghalun nillsar dhovem kel’lem tambddea kanttachem puddvem. Tacher khomis. Hem khomis puddvea bhitor ani voir judi oso tagelo bhes. Tachekodden ek Raleigh saikol axil’li. Ho lamb, ti matxi mhotvi. To saikolicher bostalo tem pollovpasarkem. Saikoli poros paim lamb zal’lean te dhomprakodden katkonant dhoddun taka pedalam marchim poddtalim. Saikol choloitanam judi varo bhorun pankhatto koxi foddfoddtali. Ani pãiakodden puddveacho xev varem bhorun furfurtalo. To saikol choloitana rodamcho ani puddveachea forforpacho ek comik avaz ietalo.

Nillule dant dhoveful’ axil’lean tache dost tachi moskori kortale. ‘Makodchap dantmanjnan haka aple jahirati khatir apoun vhorunk zai axil’lo. Poilim hagele dant dantmanjan lavun kalle kalle dakhoile mhonntokoch pod’dobhor kainch dischem nam. Fokot monxachi ek akrtai distoli. Ani magir to dant dhuta tem dakhouchem mhonntokoch dhul’le dhoveful’ chokchokit dant’ – oxem te fokannanim mhonntale.

Nillu lhan astana konnetori bhavixia sangil’lem khõi. Ho cholo zomnir ken’nach cholcho na, sodanch vahanantlean bhonvtolo. Khõichea tori eka sinemant pollel’lem: osoch ek niktoch zolmol’lo bhurgo asta. Jyotixi bhavixia kortat, hagelo ixariacher vahana dhanvtolim mhunn! Avoi-bapui khub khuxi zatat, choleachi khub apurbai kortat. Rokddoch taka zantto zal’lo dakhoila. Ani to zal’lo asta ek traffic polis. Tagelea ixariacher gaddio dhanvtat. Tannem rav mhonttokich gaddio ravtat.

Nillu-lem bhavixia oxech toren khorem zal’lem. To vahanantlean bhonvtalo. Ektor to saikolicher astalo. Saikolicher na ten’na konnache tori gaddient astalo. Choddxa bhattkarank to zai axil’lo; ektor tankam ganvaveleo gozali Nillukoddlean somzotaleo. Na-zalear apleo khobri, aplim vhoddponnam dusreakodden pavovpak tankam Nillucho upeog zatalo ani magir he bhattkar aple vangdda aplea mezar taka vaddtale.

Punn ek, jevle uprant Nillu kennach konnager ravi naxil’lo. Bail vatt polletoli, jevle bogor tixttot ravtali oxem sangun to bhattkarale gaddient bosun bod’dod ghora ietalo, ani susegad tannun ditalo.

Nillu sokallim cha ghevn zo bhair sortalo, to Gopi-lea shopar vetalo.Gopi Nillu-lo dost. Dogui vangddach xiktale. Dogui vangddach xalla chukovn chinche bottam, boram, toram paddunk vetale. Dogui vangddach Saraswati pujnak boria-boria ghorantlea porsamnim vochun borim-borim fulam chorun haddtale. Ani dogui vangddach sigar oddunk xikil’le. Gopin magir aplea bapaili kens kap’pachi kola xikun ghetli. Ani bapailem shop to cholovpak laglo.

Nilluk bapain ghor soddun kãi dovorlem na. Nilluk oddi-oddchonnik Gopich upkara poddtalo. Mhunn sokallim cha piun Nillu bhair sortalo to bod’dod Gopilea shopar ietalo. Thõi taka akh’khea Ponnjent kal kitem kitem ghoddlem tachi khobor melltali. Kal konnager kitem zalem, khõichi choli konnaborabor firta, konnalea ghorant zogddim zalim, khõichea ghova-bhailank poddna, kal konn konnak ghevun khõichea sinemak ghel’lo, voinibaien novea modelachim kanknnam kelim, tantunt tika xettin kitlem fottoilem, bi soglleo gozali tantunt astaleo. Osleo thoddeoxeo legit gozali taka mell’lear puro. Magir tea gozalink mitt, mirsang, mosalo lavn teo ruchik koso korcheo hem Nilluk xikovpachi goroz naxil’li.

Ponnjechea bhattkaramlea ghoranim Nilluchi bhumika Sanskrut nattkantlea vidushkachi astali. Hea bhattkarank hansovpachem, tanche dosh tankam hansot sangpachem, khõiche-i bai-baiechem na zalear tai-baiechem kam moneani korpachem, Satianarainachi puja zali zalear chukonastanam soglleank prasad vanttpachem kam’ Nillu bes borem kortalo. Prasadacho donno konnak chukonaxil’lo ani Nillun dilebogor ekaporos chodd donnem konnak mellonaxil’le. Samradhna asot zalear Nillu vaddunk fuddem. Kitem-i randil’lem unnem zait zalear tem xem-pon’nas lokank polloun vaddpachem kam’ Nillu bes borem kortalo. To top bhorun gheun ietalo ani zonn ekleak vichartalo, “Tuka zai? Naka nhoi?” Oxem apunnuch mhonnun, zai naka hachi vatt pollenastanam fuddem vetalo.

Sokallim dha-ank sumar Nillu nusteachea bazarant pasoi marun ietalo. Konn nustekan kitem nustem ghevun khõi boslea hem to herun dovorun doriadeger konna-i vangdda zankddam marit ubo ravtalo. Title mhonnsor khõichoi tori bhattkar gaddi ghevun nustem vhorunk ietalo.

‘Kitem Sada-baab! Aiz nustem vhorunk tum aila? Rav, rav! Tu denv’ naka. Hanv astana tum kiteak husko korta? Tum hangach rav. Hanv tuje khatir nustem ghevun ieta.’

Oxem mhonnun Nillu nustem ghevun ietalo. Magir Nillun sangil’lem poixe bhattkar ditalo. Ani Nillu panch dha rupia unnem korun te nusteakanik ditalo. Ani uril’lea poixanchem apnna khatir nustem ghevun ghora vetalo.

Deddak sumar to ghora pavtalo. Bail babddi xit bi korun ho nustem ghevun ietlo mhunn vatt polletali. Nustem uzravun tachem humonn zatasor Nillu nhanvunk vetalo. Bhãichea udkacheo panch-sov kollxe angar votun ang puxit bhitor ietalo. Bailen mirio kaddun dovril’lem puddvem nestalo. Puddveacho ek xev khandar udovn tulloxik udok ghaltalo. Ani magir bailen vaddun dovril’lem barik thandllachem xit jevunk bostalo.

Nilluli bail sadi axil’li. Hanstea mukhachi, addve kens volloun supare iedo ambaddo ghaltali. Tigelea hea ambaddeacher ful na oxem kennach zalemna. Logn korun haddil’li ten’na tigelo ambaddo nal’la iedo zatalo. Ghovak Dev somzun ti Nillulo sonvsar kortali. Konnaleo gozddeo xivun ditali, lonnchim korun, papod korun viktali. Divalle, chovthik vojim dhaddunk avoiank adhar kori. Aianom, stradhdhank sovaixinn mhunn rav. He bhaxen koxtt korun, konna mukhar hat kori nastona, ghovalo sonvsar choloitali. Nillulea avoi-bapai fattlean barik thanddllachea xitache Nilluche laad bailenuch puroile. Goddie Nilluli bail ghovale chod laad kortali dekhun Nillu kosloch kamdhondo kori naslo zanv-ie.

Hanvem poilinch sanglam, Nillu bhattkaramlo viduxok axil’lo mhunn. Sadabab ho Ponnjecho ek bhattkar. Hea bhattkarak xembor khepe mutunk vochpachi sovõi axil’li. Nillun ek khepe taka vicharlem: “Sada-bab, tuji voj kutriachi kai kitem?”

“Kiteak re”?”

“Na! Tum portu-portun mutunk veta mhunn vicharlem.”

Sada-bablea choleak Apa Kamotichi choli khubuch manil’li. Punn Sada-bab ani Apa Kamat bhitorlean ekamekale dusman, ten’na soirik zullpak kotinn axil’lem. Sada-babalea cholean apli avodd aple avoik sangli. Avoik-vhonibaik choli posont axil’li. Tinnem kitem korchem? Tinnem Nilluk afvhonno dhaddlo. Taka soglli gozal sangli. Nillun tika sanglem, “Vhonibai, tum bhienv naka. Hanv kitem korpachem tem dist kortam.” Nillu gelo thet Apa Kamotiger. Apa Kamat ani tageli bail bi astani Nillun mhollem, “Kitem, choliele laddu atam kenna ditlim tumi?”

“Are, hanvui tench mhunntam. Cholielem logn korunk zai. Nillu, tum boro-so bhurgo suchoi pollov-ia.” – Apa Kamotili bail.

“Sadababalo cholo asa nhoi? Kai boro xikil’lla sovril’lo.”

“Tu sarko asa mure? Sadabab baab kitem mhoje choliek sun korun ghetlo? Amche sombondh tuka khobor nat?” – Apa Kamat.

“Punn tu vochun Sada-babak vichar tori! Vicharunk kitem poixe poddtat vhoi?” – Nillu

“Hanvoi tench mhonntam. Choli borea ghorant poddtoli ani tumchi dusmankaiui somptoli.”

Magir Apa Kamat khoinchenuch ek dis Nillu vangdda Sada-babager gelo. Tannem utor ghalem. Ani Apa Kamoti sarko monis matso nomtem ghevun aplea dharant aila hem polloun Sada-babanui khuxalbhorit zavun Apa Kamotinle choliek sun korun ghetli.

Lhanponnant amkam Nillu avoddtalo. Kiteak, to tosleoch gozali sangtalo. Ami bhurgim thondd uktem korun tageleo khobri aikotalim. To sangi –

“Zanna mugo, lhan astana hanv Pednea ajieger gel’lom. Tenna light bin naxil’li. Ani Pednea vochunk akho dis lagtalo. Ghorant ponntteo na zalear petrolache kovde astale. Hanv ailam mhunn ajien vodde korpak ghetle. Oxi randon, randni samkar aji boslea. Randni kuxik hanv boslam. Aji vodde tollta. Randche kuddint ek il’lexem zonel. Randta astana chodd zal’lem udok bin aji hea zonelantlean bhair uddoitali … zalear… aji vodde tolltali. Itlean boddiebhaxen ek itlo hat tea zonelantlean bhitor sorlo. Fattofat avaz ailo. ‘Mhaka ek voddo di ge!’ Aji distuch vollkoli konnacho to! Tinnem kitem kelem, dovleant hunhunit tel ghetlem ani tem tea hatar ghalem, hat axil’lo bhutacho! Tem bobo huieli marit dhanvlem. Tacho avaz aikun bhõian mhoji sap’p gulli zali. Hanv Ram, Ram, Ram mhonnunk laglom. Ajien mhaka magir sanglem, ‘Bhutank ken’nach bhievchem nhoi. Bhutank zoxim ami bhietat toxinch bhutam amkam bhietat. Tum tankam bhiexit zalear tim tuka chodd bextaitat.’

“Zanna mugo, lhan astana hanv Pednea ajieger gel’lom. Tenna light bin naxil’li. Ani Pednea vochunk akho dis lagtalo. Ghorant ponntteo na zalear petrolache kovde astale. Hanv ailam mhunn ajien vodde korpak ghetle. Oxi randon, randni samkar aji boslea. Randni kuxik hanv boslam. Aji vodde tollta. Randche kuddint ek il’lexem zonel. Randta astana chodd zal’lem udok bin aji hea zonelantlean bhair uddoitali … zalear… aji vodde tolltali. Itlean boddiebhaxen ek itlo hat tea zonelantlean bhitor sorlo. Fattofat avaz ailo. ‘Mhaka ek voddo di ge!’ Aji distuch vollkoli konnacho to! Tinnem kitem kelem, dovleant hunhunit tel ghetlem ani tem tea hatar ghalem, hat axil’lo bhutacho! Tem bobo huieli marit dhanvlem. Tacho avaz aikun bhõian mhoji sap’p gulli zali. Hanv Ram, Ram, Ram mhonnunk laglom. Ajien mhaka magir sanglem, ‘Bhutank ken’nach bhievchem nhoi. Bhutank zoxim ami bhietat toxinch bhutam amkam bhietat. Tum tankam bhiexit zalear tim tuka chodd bextaitat.’

(Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 9, Março-Abril 2021)

A Goan at the UN

February 27, 2021Goan environment,Ligia Noronha,Peter Ronald de SouzaEnvironment,Global Goan

Seminário Patriarcal de Rachol salva precioso património

January 15, 2021Reitor Padre Aleixo Menezes,de Londres,Património religioso,Rachol,“Restauradores sem fronteiras”,Ângelo da Fonseca,Caterina Goodhart,Escola de Conservação de Quadros e Molduras,Goa,Seminário Patriarcal de Rachol,Londres,José Francisco de AssaRachol,Heritage

O edifício do Seminário Patriarcal de Rachol da Arquidiocese de Goa, construído pelos jesuítas no século XVII, guarda um precioso património. Em algumas das suas robustas paredes encontram-se pinturas que retratam cenas bíblicas, a vida dos santos, e elementos da doutrina católica. São reproduções de quadros de artistas renascentistas: Rubens, Rafael, Miguel Ângelo e Caravaggio.

Outras pinturas dizem respeito aos Patriarcas da Arquidiocese e a fundadores de ordens religiosas. Vêem-se também obras de Ângelo da Fonseca, conhecido como o “Pai da Arte Cristã Indiana”.

Trata-se de mais de 150 pinturas executadas por artistas locais entre os séculos XVII e XX, em três formas: frescos, telas e óleo sobre madeira.

Por falta de recursos humanos e financeiros, essas pinturas foram deteriorando ao longo dos tempos. A partir do ano de 2017, graças à iniciativa do Reitor Dr. Padre Aleixo Menezes e à boa-vontade de Caterina Goodhart, directora da Escola de Conservação de Quadros e Molduras, de Londres, vários goeses e estrangeiros por ela treinados, ajudaram a restaurar as obras de arte, no âmbito do projecto intitulado “Restauradores sem fronteiras”, iniciado pela profissional londrina.

Até hoje estão restauradas as seguintes pinturas e imagens:

- Retratos dos Patriarcas Mateus de Oliveira Xavier, Teotónio Vieira de Castro, José da Costa Nunes e José de Vieira Alvernaz;

- Tela da autoria do general José Francisco de Assa, a qual retrata o Rei Dom Sebastião, que facultou a construção do Seminário;

- Uma outra, setecentista, representando a levitação de S. Francisco Xavier, no acto de administração da Sagrada Comunhão;

- Retratos de Maria Madalena, Santo António e o Menino Jesus, em estilo flamengo.

As obras do Seminário não só valem em si mas também por serem trabalhos de artistas locais. Reforçam a história e identidade artística do território, além de serem um óptimo meio de transmitir a Fé. Nas palavras do padre Victor Ferrão, professor do mesmo seminário, são elas uma “imagem do céu na Terra” e constituem uma “Bíblia visual” nas paredes.

(in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Fev de 2021)

Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

January 15, 2021O Heraldo,‘Página dos Novos’,Portugal,Rosa Lobato de Faria,Indo-Portuguese poetry,Morgadio of Nerul,Lyceum in Goa,Leão Fernandes,Carmo Azevedo,Egipsy de Sousa,Panjim,António Maria da Cunha,Goa,Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria,Carnaval,Prazeres da Costa,Salvador FernandesPersonality,Interview

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

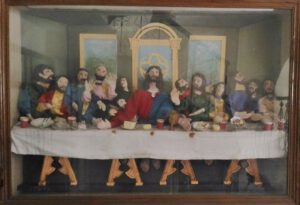

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

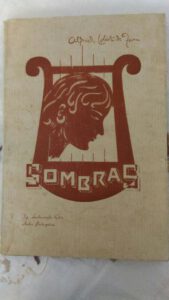

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

Looking back, looking forward

As the clocks ticks away, I can't help looking back on the year that was: a year full of ups and downs and challenges at every nook and corner. That an infinitesimal virus could hold the world hostage goes on to show how helplessly small proud humans truly are in the order of the universe. We are invited to appreciate the mystery of life and to realise that God is the overarching reality.

Here we are, on the threshold of 2021! There is a lot to be thankful for and a lot to be hopeful about. As we look back on 2020 and forward to 2021, St Paul helps put things in perspective: "We know that God causes all things to work together for good to those who love God." (Rom 8:28)

That's so very true. When we love God all things begin to fall in place, all things begin to make sense.

Happy New Year to all my esteemed readers!

Porque não vem a morte…

November 22, 2020Goan Konkani short story in translation,Konkani-Portuguese literary translationShort Story,Translation

Um conto de Damodar Mauzó

Um conto de Damodar Mauzó

Traduzido do concani por Óscar de Noronha

É meio-dia. O sol, qual inimigo implacável, agride brutalmente a pele. O chão cá abaixo, o céu lá acima, e ardem as criaturas como as brasas do fogão a lenha! De todo o lado, um calor de escaldar.

Já lá foi o mês de maio, e o de junho está quase no fim, porém, não há sinal da monção. O solo quente, seco e mirrado de sede, olha súplice para o céu. Não há uma só nuvem no firmamento. Volve então os olhos queixosos, mas ai, não era capaz de verter uma só lágrima.

As mangueiras, as jaqueiras, as árvores de gralha e as palmeiras – murcharam todas elas, coitadas. Queimaram-se as folhas; as sobreviventes estão crestadas. E as arvoretas! Ora bem, vivem porque não lhes veio a morte…. Se é esse o estado das árvores, nem queira saber o que é da erva e do arbusto! Há muito que a erva se desenraizou, e ora lá se vê só areia. E os arbustos? Encontram-se no seu lugar umas esguias estacas.

As várzeas confundem-se com as hortas. Os poços secaram um por um; e as lagoas ressecaram. Até a sua lama se transformou em pedregulho. Os seres humanos da região safaram-se para terras longínquas. Os pássaros migraram para outros países. Pereceu o gado. Tudo que sobrevive espera a morte.

Nesse sol abrasador do meio-dia, passa por lá uma cobra-d’água levando consigo o seu rebento. Vai em ritmo acelerado. Faria algum sentido sair a essa hora? De mais a mais, é cobra, cuja natureza é de se arrastar pelo chão. Devia-lhe arder o corpo; pelos vistos, a cobra-d’água não se dá conta disso. Vai andando, com os olhos postos no filho. Quem visse essa cena não deixaria de lhe chamar louca. Mas... quem vai reparar nisso?

A cobra-d’água atravessa várzeas, hortas e valados. Deparando com um coqueiro, à sua sombra faz uma breve pausa; suspira e põe-se de novo a caminhar com o filhote. Ela própria não deve saber para onde vai.

A certa altura, encontra uma várzea. Ó minha mãe! Que tamanha que ela é! Mas evitando pensar nisso e de se deter na soleira, desce do valado e percorre os cômoros da várzea. Ó senhora minha! Quem a visse agora, não deixava de lhe dizer com dó: "Cobra-d’água, por que andas à soalheira do meio-dia? Contas pelo menos chegar ao outro lado? Cuidado com a tua vida! Melhor era voltares atrás para este valado. Fica ao pé desta árvore-de-gralha até à tardinha!…" Mas a cobra-d’água não se dispunha a ouvir. Nem tomaria a peito esse conselho. Quando muito, diria de passagem: "Olha, não há tempo para descansar! E que importa que eu morra no caminho? Ora, só porque a morte não vem..."

Essa várzea tem até os cômoros já desmoronados. Só se faz sentir a areia, essa areia quente! Lembra-se de quando, à cata de um rato, entrara na casa do José, vendedor de grão assado. Ficara num canto a observá-lo. O José havia deixado ao lume uma grande panela de barro, em que metera areia. Sobre esta, depois de bem aquecida, vazara grão, e ora... ao caminhar, arrepiou-lhe o corpo de se imaginar ela própria o grão sobre a areia!

‘Ai-ai!’ suspirou a cobra-d’água ao ver um valado que, à borda, tinha um anacárdio – árvore de bibó! Ansiando por um pouco de sombra, acelerou o passo e chegou-se ali. Subiu com algum esforço e meteu-se debaixo da árvore. Ó senhor! Onde está o seu filho? Até há pouco estava com ela. Aflita, voa pelo trecho do valado, quando afinal estava mesmo lá em baixo. Julgando que tinha dificuldade em subir, a cobra-d’água saltou, para prestar ajuda. Caramba! Porque está assim inerte? Ela só dá com o caso quando lhe toca com a cara….

Com a morte na alma, subiu de novo ao valado. Não tinha o mínimo de forças para levantar o corpo do filho. Sentou-se debaixo da árvore, a pensar. Passaram-lhe então pela mente um incidente após o outro.

Quando vivia o marido, não faltava nada à cobra-d’água; satisfazia-lhe todas as necessidades. E como adorava ele os filhos! Mas… não era essa a vontade divina. Um dia, o marido teve de sair à busca de alimento. Como tivesse muita sede entrou numa pia anexa a uma casa, à procura de água. Estava lá um caldeirão. Ó que sede de água! Desejando satisfazê-la, meteu a cabeça nessa panela. Entretanto, um malvado quebrou-lhe a coluna vertebral com uma paulada nas costas. Mesmo assim, a cobra-d’água, às escondidas, arrastou-se até à casa. Tentaram de tudo para a salvar, mas...

Ora, a cobra-d’água sentia vontade de morrer... Que tinha mais a fazer na vida? Mas não podia ser! O marido, à beira da morte, havia-lhe aconselhado a tomar conta dos filhos. Por isso, viveria só por amor aos dois. Porém, foi cruel o destino! Ambos –

Já o verão estava no fim, sem que houvesse o menor indício de chuva. Secos os poços e ressequidas as lagoas, nem para mezinha havia sequer uma gota de água. Nessas circunstâncias, a cobra-d’água superou todos obstáculos para cuidar dos filhos. Privou-se a si própria, mas não os filhos. Donde é que lhes arranjaria água dado que à própria terra escasseava? Entretanto, de sede morreu-lhe uma criança; e ficaram elas duas, a mãe e uma outra. Esvaziara-se toda a região. Haviam partido as serpentes, as cobras de rato e todas outras. Ficara só a pobre cobra-d’água, na expectativa de que viesse a chuva sem mais delongas. E só quando não podia mais, abandonou os seus bens, pegou no filho e partiu... E agora, este mesmo filho deixou-a!

A cobra-d’água derramou duas lágrimas.

‘Porquê choras, cobra-d’água querida?’ – de repente, ouviu ela uma voz, afectuosa, que lhe fez lembrar a do marido – e logo rolaram mais duas lágrimas.

‘Por amor de Deus, não chores assim!'

A cobra-d’água, cismada, lançou um olhar ao redor. Não estava ninguém no valado; além da árvore de bibó, nem uma planta sequer. Então, seria mesmo o bibó–?

‘Sim, sou eu mesmo, o bibó, que te estou a falar. Porque choras?’

Fitando a árvore, com os olhos marejados de lágrimas, e a sentir-se já um tanto aliviada da dor, soltou um grande suspiro e contou-lhe a sua história. Comoveu-se muito o bibó! Mas que podia ele fazer? Suspirou e guardou uns momentos de silêncio. Perguntou-lhe então a cobra-d’água: 'Ó bibó, estás aqui só, não estás? Isso não te aborrece?’

‘Que remédio? Dantes, tinha a companhia das trepadeiras e dos arbustos, e ali na borda estava uma palmeirinha. Mas... mas hoje, estou cá sozinho, a contar os dias. Quando me lembro dessa palmeirinha, fico triste! Nem coco verde chegou a dar; entretanto, foi-se embora, coitada!’

‘Não leves a mal esta pergunta, bibó!... O que te faz viver?'

Dentro em pouco, respondeu o bibó: ‘A minha vida já não faz sentido. Sei muito bem que mais dia, menos dia, hei-de morrer. Estou vivo, cobra-d’água... estou vivo somente porque não vem a morte!...’

O bibó vive porque não lhe vem a morte! Também eu vivia porque não me vinha a morte? Não! Vivia mas era por causa dos meus filhos – e sim, quem tenho eu agora? Porquê viver?

‘Entendo. Ó cobra-d’água, já sei o que estás a pensar. Ouve bem! Existem muitas criaturas no mundo. Umas estão desapontadas; outras sentem-se livres por terem já cumprido os seus compromissos, os seus deveres. Estas não pensam na morte; vivem pacatamente, aguardando a sua hora… E tu não deves morrer! Ouve lá! Existe uma lagoa a umas sete ou oito léguas a leste daqui. É pequenina. Vai tu ficar nesse lugar. Ninguém conhece o sítio, e não me parece que chegue lá alguém! Vai lá viver. Pronto, tens de viver, pelo menos porque te não vem a morte.”

Levantou-se a cobra-d’água; olhou para o bibó e começou a lacrimar.

‘Cobra-d’água, queiras fazer-me um favor!’

‘Diz, bibó, diz! Estou às ordens. Queres que eu fique aqui mesmo?’

'Não, cobra-d’água. Se ficares aqui, não viverás. Tens de ir mesmo. Mas antes disso, faz-me este favor...’ disse o bibó, emocionado. ‘Há mais de um mês que não vejo nenhum ser vivo. Hoje vieste tu. Seria um favor se por uma última vez serpeasses, à vontade, sobre o meu corpo…'

A cobra-d’água subiu num instante. Chegou até ao topo, trepando-lhe o ombro e enrolando-se-lhe à mão. E desprezando a sua própria dor, brincou e dançou, antes de descer da árvore. O bibó ficou muito contente. Então, a cobra-d’água volveu um derradeiro olhar ao filho e uma comovente despedida ao bibó, e pôs-se em direcção a leste.

O mesmo impiedoso sol. Chega o final da tarde, mas a terra está quente na mesma. O grande astro, a caminho do ocaso. Chega a tardinha. Põe-se o sol e some-se. Os seus raios vermelhos espalham-se pelo chão. A terra, que sempre a esta hora se apresentava tal qual uma noiva, parece hoje muito enferma. A cobra-d’água volta a andar e sempre a lamentar esse triste estado ambiental. Passa o lusco fusco e vem a noite, e ainda a aurora. Entretanto, a cobra-d’água, sonolenta, não se atreve a repousar: que será dela se inesperadamente cair num sono profundo? Tinha de chegar quanto antes àquela lagoa…. Ó esperança, já algum dia esqueceste alguém?

Mais um meio-dia; e o mesmo calor ardente! A cobra-d’água segue o seu caminho, sem o mínimo de descanso. Passa o meio-dia e vem o crepúsculo… Que é isso? Como secaram assim as plantas! De todos os lados parecem elas uns postes desnudados, e ainda no meio delas, umas plantas viçosas! Espanta-se a cobra-d’água, mas não se deixa ficar por lá.

… Era esta a tal lagoa! Haviam sobrevivido as plantas, só por estarem à sua margem! Seja como for, a cobra-d’água chegou! E então, que límpida essa água! Fica a cobra d’água a admirá-la por uns momentos. Logo depois, saindo do seu transe, vai até à beira da água. E quando a ia tocar com a sua língua sequiosa, lembrou-se do marido. Morrera precisamente ao beber água!... E dos filhos – haviam deixado o mundo angustiados por falta de água para beber!... E morre o bibó por não haver água – anseia morrer, mas vive só porque lhe não vem a morte.

Escurece. Com passos suaves, vem a noite. A cobra-d’água avança. Mergulha-se na água; há dias que não a via! Bebe até dizer basta; dança, brinca, nada, cai de sono… e dorme.

Splash! Splash! Desperta a cobra-d’água, intrigada com esse som logo à aurora, e vê lá gente! Cheia de medo, afunda rapidamente a cabeça; e quando a retira, vê um jorro de água a encher um camião-tanque. Assusta-se! Em tempos, vira bombear a água duma várzea. Que raio de seres humanos! Só Deus sabe como descobriram essa lagoa! Irão levar esta água e dentro em pouco não haverá mais! E… e… depois –

Baixa o nível da água; reduz-se a metade; e logo resta lá muito pouca… E –

‘Ei! Vejam aí, uma cobra-d’água!' grita alguém.

‘Traz-me um pau!... Anda cá….'

A cobra-d’água cerra os olhos. Tem saudades do marido e sente-se feliz por saber que vai ter morte igual à dele. Tem saudades também dos filhos – foi bom terem partido antes dela! E aquele bibó! Deve estar ainda a aguardar a morte! Porque não vem a morte….

‘Ai!’

'Valente! Foi um golpe de mestre!

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 7, Nov-Dez 2020

Moronn Iena Mhunn...

November 15, 2020Short Story,Transliteration

Damodar Mauzo-hachi lhan kotha. Devanagarintlem Romi lipiantor korpi: Óscar de Noronha

Damodar Mauzo-hachi lhan kotha. Devanagarintlem Romi lipiantor korpi: Óscar de Noronha

Donpar zal’li. Vot samkem dusman zal’le bhaxen angache kuddke kaddtalem. Ponda zomin ani voir vell. Randnicher dovoril’lia dhondsavari soglle jiv hulpatale. Charui vatten rokhrokh.

Mai ken’na kobar zalo. Jun-ui sompot aila. Pavsachem nanv nam. Dhortori taplea. Udkak haphaplea. Tanen tanelea. Aaxen babddi mollbak dolle laita. Punn mollban ek kup legit dixtti podna. Roddkuri portota ti. Punn golloitli mhollear dollean ek olem dukh legit iena.

Ambe, ponnos, vodd, madd soglle babdde bhavun geleat. Panam zoddleat. Ani zancher asat tim korpun geleat. Ani zhaddam! Moronn iena mhunn jietat. Vhoddlea rukhamchi oxi ghot. Magir tonnanchi and zhompachi khobor kitem vicharta! Tonnan dhortorek ken’na sodil’li. Tea zagear fokot renv dixtti poddta. Ani zhompam? Tanchea zagear distat ubeo boddio.

Xetam ani mollam ekuch distat. Bhãio ekan’ek poddong poddleat. Tollim sukun geleant. Thõicho rebo legit sukun fator zala. Ganvant ravpi moniszat ganv soddun pois gelea. Sovnnim sogllim dusrea dexant geleant. Gorvim sogllim morun geleant. Jogun vattavn uril’lea jiv moronnachi vatt polloitat.

Ani oslea vellar, donparchea kaddar ek henvallem aplea pilak borobor ghevn khõi tori veta. Soddsoddit cholta tem! Oslea vellar ani cholpachi mannsuki asa? Tantun henvallem tem! Sogllem ang bhuiek ghasun cholop tachem. Ang samkem lasta astalem. Punn henvalleak tachi jannvik asa-xi disona. Tem pilak samballit fuddem sorot asa. Konnui polloit zalear taka pixant kaddle bogor ravcho na. Punn… asa konn taka polovpak thõi?

Xetantlean, molleantlean, banda voilean tem cholta. Modinch madd dislo mhonntokir tem savllent khinnbhor ravn huskare soddta ani pilak ghevn fuddem cholpak lagta. Khõi veta tem tachem takach khobor asona.

Veta veta taka ek xet lagta. Avoi mhojea! Kedem vhoddlem xet hem. Punn ievzupak vell na ani votant ubem ravpachi mannsuki na. Bandha voilem denvun tem atam merê voilean cholpak lagta. Avoi avoi! Taka pollovpak thõi konnui asto tor tachi kakllut korun sanglem bogor na ravto – ‘Henvallea, aslea donparchea koddar kiteak veta tum? Poltoddin pavxi tori mu-go? Jiv vochot tuzo. Fattim sor ani hea bandhar io. Sanz meren rav hea vodda kuxik!...’ Punn henvallem tem aikupak naxil’lem. Tem ullovnnem monaruch ghenvchem naxil’lem tem. Choddxem zalear vetam vetam sangtem – ‘Arê, baba, suseg ghevpak vell konnak asa? Ani veta veta melem mhunn porva konnak asa? Atam moronn iena mhunn….’

Hea xetacheo merôi-bi kosol’leat. Fokot renv lagta angak. Hun’hunit renv! Henvalleak iad zata – ek dis chonnekar Juze-lea ghorant undrachea pilak dhorpak mhunn gel’lem tem! Thõi tannem kuxik ravn polloil’lem Juzen ek vhodd matie budkulo ujear dovril’lo. Tantun renv ghal’li. Ti tapt’kir tannem tantunt chonnem votil’le ani magir… choltam choltam ang xirxirl’lem tachem. He hun’hunit renvent apunnui bi tea chonnea bhaxen –

Hush’sh’! Henvallem huskarlem. To polloi bandh. Bandha degeruch ek zhadd asa bibeachem. Savlli tori mellteli matxi. Henvallean chal soddsoddit keli ani tem bandhar pavlem. Nett korun voir choddlem. Rukha ponda gelem. Arê, pil khuim? Arechea! At’tam axil’lem. Akant ailo tacher. Dhanvlem tem bandhar savn. Polloit zalear sokoluch asa tem pil. Voir choddpak zaina zatlem oxem mhonnun henvallean sokol uddki marli. Ab’ba! Hem ozun oxem oggi kiteak poddlam? Angak thond thenkov’n polloi zalear –

Dukhi monan henvallem voir sorlem. Tea pilak ghevn voir choddpa itli legit xokt tachea angant naxil’li. Tea rukha ponda tem boslem. Ievjita ievjita taka ek ek gozal iad zavpak lagli.

Tea pilacho bapui astana henvalleak khãich unnem naxil’lem. Magta tem to haddun ditalo taka. Kitlo mog axil’lo tacho bhurgeancher! Punn… Devachean tem polleunk nozo zalem. Ek dis to khavpak sodunk mhunn bhair gel’lo. Thõi to tanen tanel’lo mhunn udok sodunk laglo. Eka ghora kuxik manneant ek bhann axil’lem. Tanel’lo jiv! Pottbhor udok pit’lom mhunn tannem tokli bandda bhitor ghali. Itlean eka duxtt monxan tache fattir boddi marli. Fatticho manddko moddlo tacho. Tosoch lip-lipot to ghora ailo. Khub upai kelo – punn…

Henvalleak dixil’lem atam apnnei morchem…. Kitem korchem asa jitem ravn? Punn na! Morta astana ghovan taka sangil’lem, hea bhurgeank bore bhaxen voir kadd. Hoi! Hea don bhurgeam khatir mhaka jitem ravunkuch zai. Punn noxibuch futtkem! Donui –

Gim somplo punn pavsuch na. Bhãio sukleo. Tollim attlim. Vokhdak legit udkacho themb na zalo. Oslea vellar torektora korun henvallean pilank poslim. Khasa apunn upaxim ravlem. Punn tankam pottak marli nat. Punn zhõi dhortorekuch udok mellna thõi ti tori khõichean ditli? Udok udok mhonnit ek pil gelem. Urlim dogam. Pil ani avoi. Sogllo ganv rito zalo. Sorop, divodd, soglle gele. Ul’lem tem henvallem. Babddem az na faleam pavs aile bhogor ravcho na mhunn axen ravil’lem. Punn samkench ranv nozo zalem toxem tem uttlem. Santtlim-pottli soglli udovn, pilak ghevn tem bhair sorlem…. Ani atam tem pilui bi taka soddun gel’lem.

Henvalleachea dollean don dukham gol’ lim.

‘Roddta kiteak go tum, henvallea!’ okosmat avaz ailo, maiest avaz. Henvalleak ugddas ailo – aplea ghovacho. Ani tachea dolleantlean anikui don dukham ghollim.

‘Oxem roddunaka pollov’ia!’

Henvallean ojapan polloilem. Bandhar tor konnuch na. Ek zhadd legit na. Fokot bibea zhadd soddlear. Bibea zhadd tor nhoi mu?

‘Hoi. Hanvuch to bibo uloitam. Tum roddta kiteak?’

Bhoril’lea dolleamnim henvallean tea rukhak polloilem. Tachem dukh ekdom lhov zal’le bhaxen taka dislem. Ek vhodd suskar soddun henvallean soglli gozal taka sangli. Bibo! Vaitt dislem taka aikun. Punn kortolo kitem? Suskaro soddun to oggich ravlo. Henvallean vicharlem: ‘Bibea, tum ektoch hanga asa? Tuka vaz iena?’

‘Kitem kortolom? Poili mhojea sangatak vali axil’leo. Zompam axil’lim. Te deger ek kovathoi axil’lo. Punn… punn az hanv hanga ekttoch asam. Dis meztam. Tea kovatheachi iad zali mhonnttokir vaitt dista mhaka. Azun bondde legit ievunk naxil’le taka. Gelo bhavddo!’

‘Vichartam mhunn ragar zanv naka, bibea. Tum jieta kiteak?’ henvallean vicharlem.

Kãi vell ogi ravn bibean zap dili, ‘Mhoje jinnent atam kãi orth na. Hanv boro zannam, faleam ek dis hanv mortolonch. Hanv jietam, henvallea, mhaka moronn iena mhunn jietam –‘

Bibo moronn iena mhunn jieta! Ani hanvui moronn iena mhunn jietalem? Na! Hanv jietalem mhojea bhurgeam pasot – punn atam mhozo konn asa? Hanv kiteak jievum?

‘Mhaka kolltta. Henvallea, tuje vichar mhaka kollttat. Mhojem aik. Hea sonvsarant zaite jiv asat. Khub zann nirxeleat. Zaite zann apnnalim kortubam, apnnalem kortovio korun meklle zaleat. Punn te mornnacho vichar korinat. Te ogi bosun jietat. Mornnachi vatt polloit. Tuvem morunk favna. Mhojem aik. Hangasan udentek sat att konsar ek tollem asa. Lhan’xench asa. Tum thõi vochun rav. Azun meren thõi konn pavunk na. Ani konnui pavotxem disona. Tum thõi rav. Chol, atam tunvem moronn iena mhunn tori jievunk zai.’

Henvallem uttlem. Bibeak polloun tache dolle bhorun aile.

‘Henvallea, mhojem ek kam’ korxit?’

‘Sang, bibea, tum sangta tem aikotam hanv. Sang, hanv hangach ravum?’

‘Na, henvallea, hanga ravlear tum jievchem na. Tuvem vochumkuch zai. Punn voch’chem fuddem mhojem ek kam kor…’ bibeacho avaz katortalo. ‘Mhoino zalo, mhoje sori konnuch jiv ievunk na. Az tum ailam. Upkar korun mhojea angar ekuch favt meklleponnan bhonv….’

Sor’sor korun henvallem voir choddlem. Tengxer pavlem. Khandar choddlem. Hatacher bhonvlem. Aplem dukh visrun tem khell’lem. Nachlem. Magir sokol denvlem. Bibo khuxalbhorit zalo. Ek favt aplea pilak dollebhor polloun ani bibeacho ontoskoronnpurvek nirop ghevn henvallem udentek thondd korun cholpak laglem.

Tench rokhrokhit vot. Sanjevell zait ailea punn bhuim titlich hun asa. Vell ostontek lokla. Korta korta sanjevell zata. Vot denvta. Na zata. Tambddim kirn’nam dhortorecher pattollttat. Sodam hea vellar voklevori dispi dhortori az hantunnar poddil’lea vaittkara bhaxen dista. Soimek ail’li hi avkalla polloit henvallem fuddem sorta. Tinsanz zata. Rat sorta, fantodd zata. Henvalleak jem ieta. Punn nhid kaddpachi mannsuki na. Nhidlear thõich sust nhid lagli zalear? Poilim tea tollea kodden pav’ia. Aast! Tinnem konnak soddlam?

Porot donpar! Porot rokhrokh! Mat legit suseg ghenastanam henvallem vatt cholta. Donpar sorta. Tillsanz zata ani… Arechea! Tim zhaddam oxim koxim zogleant? Charui vatten sukheo boddio koxim zhaddam ani modinch panchvea pananchim zhaddam koxim? Ojapan henvallem fuddem sorta.

… Hench tem tollem! Tollea degevoilim zhaddam him, mhunn togleant borim! Zanv! Pavlem nimannem kodden. Ab’ba! Ani udok tori kitlem nivoll! Kãi vell ojapbhorit zavn henvallem thõich ubem ravta. Magir ekdom’ zagear ievn fuddem sorta. Udka moreant ieta. Tanel’li jib udkak tenkovpak taka iad ieta ghorkarachi. To udok pietnach mel’lo! Bhurgeanchi – udkak vollvollun tanni sonvsar sodil’lo! Ani bibo udok nasun morta – morn’nachi vatt polloita, moronn iena mhunn jieta!

Kallok zata. Rat mond pavlamnim ieta. Henvallem fuddem sorta. Udkant veta. Kitlea disanim tem az udok polloita. Pottbhor pievn gheta. Nachta, khelltta, penvta. Ani dolle jemetat. Henvallem nhidta.

Gasgass! Gasgass! Fanteaparar ho avaz koslo mhunn tokli voir kaddun polloi zalear monxam dixtti poddtat. Bhievn henvallem tokli bhitor ghalta. Portun tokli voir kadd zalear udkacho ghogo vanvta ani tem udok eka truck-hacher ttank’ient poddta. Henvalleak sot’tt zata. Tannem adim polloil’lem xetant pump lavn udok uspitat tem! Padda poddum he monis zatichem. Khõichean tankam hi khobor kol’li Dev zanna! Atam hem udok te vhortole. Il’lem il’lem korun somptolem hem udok! Ani… ani… magir –

Udok denvta. Ordhem zata. Thoddem urta. Ani – ‘Arê, tem polloiat. Henvallem!’ konn tori add’dota.

‘Boddi hadd re ti!... Tum oso io…’

Henvallem dolle dhampta. Taka ugddas ieta – ghovacho. Ghovachench moronn apnnakui ietlem mhunn khinnbhor borem dista. Bhurgeancho ugddas ieta – borem zalem, poilim gelim tem! Ani to bibo! Azunui to moronnachi vatt pol’loit astolo! Moronn iena mhunn….

‘Ã…’

‘Xabass, dhopkeak uddoilem mure!’

(Poilem xap'la Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 7, Nov-Dez 2020)