“The Fado in Goa is going to be a revolution!”

November 14, 2020Fundação Oriente (Goa),Fado de Goa,‘Fado in the City’,Orlando de Noronha,Instituto Camões,Taj Group of Hotels,Tipografia Rangel,Ustaad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar,Spic Macay,Carlos MenesesFado,Interview

You can listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUDFr-Lauqo

O.N.: Let’s begin our chat with an incident that occurred in November 2017, that is, two months ago. Sónia, you received the Ustaad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar (National Youth Award) from the Government of India, in the traditional music category, which included Mandó, Dulpod, Dekhnni, Konkani Tiatr music and even… the Fado!!!

S.S.: That’s true!!

O.N.: That’s a great achievement, for it was finally Sónia who made sure that the Fado entered the history of India, and it is now registered as part of the Indian traditional music category...

S.S.: … traditional music of Goa!

O.N.: Congratulations!!

S.S.: Thank you!!

O.N.: It is well known in Goa that you recently launched a very interesting project called ‘Fado de Goa’. Could you enlighten us on this?

S.S.: The project ‘Fado de Goa’ started in the beginning of 2017 and was a result of another project from the year 2016 called ‘Fado in the City’ – a series of 10 concerts, at various venues in Goa. The idea was to take the Fado to audiences that had never heard, never attended a concert of Fado. At the ‘Fado in the City’ concerts we’ve always had people that neither spoke nor had any family member that spoke Portuguese. And I think this was the winning point of ‘Fado in the City’. And from there appeared the second project, ‘Fado de Goa’…

O.N.: And thanks to this new project, ‘Fado in the City’ could well be rechristened ‘Fado in the City and Countryside’!!

S.S.: Absolutely! ‘Fado de Goa’ is a different project. These are not concerts but Fado classes. With sponsorship by the Taj Group of Hotels and Resorts we conduct Fado classes. What is interesting is that in Lisbon, which is the land of the Fado, there are no Fado classes, no Fado schools, no Fado teachers. There are Fado singers, obviously, because it is in their blood and soul, and the Fado is in the Lisbon air! But here in Goa, we need classes of Fado… especially the present generation needs it, for they don’t have the contact that Goa earlier had… That’s because Fado has existed in Goa since the 1800s. We have books that prove that the Fado was already here in the 19th century. Fado was born in Lisbon around the 1830s or 40s, and arrived in Goa as early as the 1890s, or maybe even earlier.

O.N.: But can we be sure that it was Goans who used to sing the Fado, or was it the Portuguese that lived here?

S.S.: The Goan people! Because the booklets that I have, which were printed and published here by Tipografia Rangel, in Bastora, have lyrics and notations of the Fado as well as the Mandó. So, it had to be for people that spoke Konkani.

O.N.: Yes. And just out of curiosity, what were the titles of these fados?

S.S.: There was one titled “O Órfão” (‘The Orphan’) and another, “Fado”.

O.N.: You mean, it had the lyrics as well as music notations…

S.S.: Yes, the lyrics and the music notations! They were booklets for music students to play and sing fado, mandó and other forms.

O.N.: Interesting!

S.S.: Yes, indeed! So we know that the fado has been living here for all this time. Thus, it is one of the forms of traditional music of Goa.

O.N.: And have these fados been performed in Goa? For example, how would it feel to sing “O Órfão” today?

S.S.: I don’t know if they could be performed in our time, as the language has also evolved. We are talking of a time span of 200 years back from now. Even in Portugal the spoken language is way different today. And in the fado, lyrics have evolved, the manner of writing the stanzas as well as performing the fado, has changed. So, while I’m not sure if those fados could be performed today, yes, an attempt could be made to modify those old lyrics. Maybe! Who knows!

O.N.: Right! One never knows how it will play out… Well, let’s talk now about the Fado classes. What fados are the students learning to sing?

S.S.: In the classes that we have had it was not only singing that was taught but also theory about the Fado, because there is a misconception in Goa that any song in Portuguese is a fado. Which is not so! So, we had to teach the rules of the fado, its history and origin, famous Fadistas – Maria Severa, Amália... of course – the instruments used in the Fado, the places where fado is sung live, areas of the Fado in Lisbon, like Alfama, Bairro Alto and Mouraria; the various categories of fado, what exactly is traditional fado, and such topics. So, it is theory as well as Fado singing that is taught…. We’ve already had four groups, the first being in Margão, the second in Panjim, the third in Vasco da Gama and the fourth again in Margão.

O.N.: So there has been interest...

S.S.: Yes! And now they’ve invited us to have a batch in Mapusa plus a second batch in Vasco da Gama.

O.N.: And what are the age groups?

S.S.: We’ve had batches of about 30 students and in Vasco we ended up having 60 students. From school children up to grandparents!! At times it was such a cute sight!... There were members of the same family, like parents and children, siblings, cousins; we even had a pair comprising a grandfather and his granddaughter… studying together for the final exams. Because there is an exam for all students, written as well as orals.

O.N.: What is the duration of the course?

S.S.: The course is of 10 weekly classes. But at times we had to postpone classes due to school exams or feasts; we’ve had breaks. So considering everything, I would say it takes about 15 weeks. At the end of this, a ceremony is held where the students are presented a certificate. There are no ranks or grades given; the certificates simply say that the student has completed the course held by Fado de Goa. Because in Lisbon itself, there are no formal courses of Fado, and we are no authority to grade...

O.N.: Who else is associated with the project? For sure, you have a team…

S.S.: Oh, for sure! Absolutely required. The main support comes from the Taj Group of Hotels, who under their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to protect a dying art form have chosen the Fado in Goa... Our team comprises Musician Carlos Manuel Meneses, who is present at all the classes, to accompany the students as they learn. We have an administrator in Marlene Meneses, who coordinates the groups, admissions, communication, etc. We have other musicians, like Orlando de Noronha and Dr Alan Abreu; and we have heads of Fundação Oriente (Goa), Instituto Camões; Spic Macay, which works to protect the classical music of India and are going to include the Fado in that list. So that’s our steering committee. We have meetings to decide and steer the project.

O.N.: So it is really a large-scale project...

S.S.: Yes, indeed! We hope to discover 100 fadistas in Goa!!

O.N.: Excellent! And for sure you hold the key to that…. Well, talking of the Fado, you must have musicians, too... What about training musicians?

S.S.: Yes, we do need to! From among the students of our four batches, after the exams, we’ve selected students to go to the next level. They are students with potential to sing and who we will train to become fadistas to sing on stage, not merely at parties… and that is where we require musicians. We hope to have a workshop – not finalised when! – of Guitarra Portuguesa (Portuguese Guitar) as well as Viola de Fado (Fado Guitar), for sometimes we can sing the fado without the Portuguese Guitar but we can’t do without the Fado Guitar! It is easy, because here in Goa we have so many extremely talented musicians who already play the classical guitar, and only need to learn the technique of accompanying the fado. That’s all.

O.N.: Very well! So, we wish you, Sónia, all the best in the project, which doesn’t look like a mere project but an adventure with the Fado!...

S.S.: A revolution!

O.N.: A revolution, indeed! We wish you all the best in this adventure and revolution!

Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 7 (Nov-Dec 2020)

Pangim da minha infância

November 1, 2020Mandovi,Palácio do Idalcão,Covid-19,Barco de Bombaim,Bloqueio Económico de 1955,Fontaínhas,Opinion PollGoa,Memories

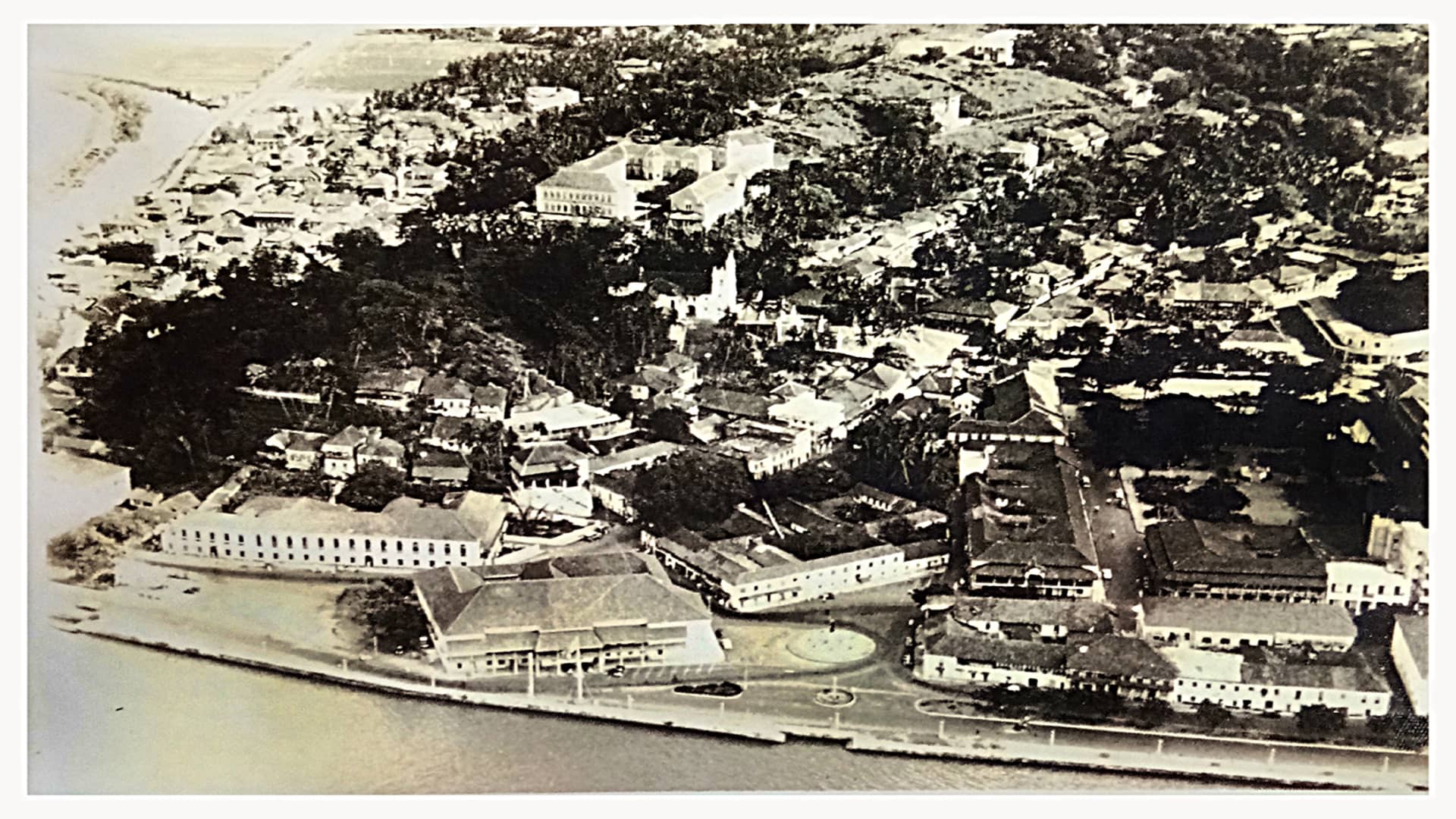

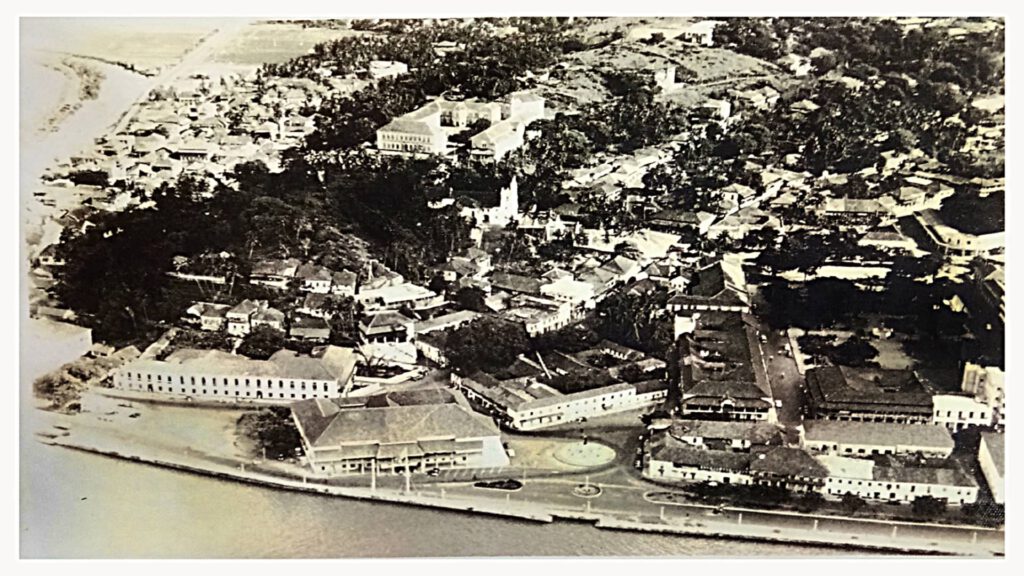

Nas décadas de 60 e 70 do século XX, a cidade de Pangim era a imagem da calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro. Estendia-se da Rua de Ourém ao Hospital Militar (na direcção leste-oeste) e da avenida marginal ao Altinho e Batulém (na linha norte-sul). Como jardim à beira-mar plantado, a quem o suave Mandovi pautava o ritmo da vida, Pangim tinha uma identidade própria e um encanto muito seu.

Vivia eu no coração de Pangim, ao pé do antigo Palácio do Idalcão e sob o olhar hipnótico do Abade Faria. Raiava o nosso dia com o chilrear dos pássaros, seguido da sonora sereia do barco de Bombaim a atracar no cais da Alfândega. A essa hora, o vaivém apressado da multidão, a algazarra dos bagageiros e a buzina dos táxis na Avenida Vasco da Gama (hoje D. B. Marg) eram um chamariz para uma boa parte dos 40.000 pangimnenses ainda envoltos em sono; um impulso matinal para as suas tarefas, sobretudo a escolar.

Era como se o frenesi da metrópole indiana tivesse acabado de desembarcar na capital goesa! Essa onda pressurosa propagava-se um pouco por toda a parte, a começar pela Avenida Dom João de Castro e a Rua Afonso de Albuquerque (ora M. G. Road), as principais artérias, dominadas pela burocracia e pelo comércio. Com a partida daquele barco, no meio da manhã, a cidade voltava à calmaria; almoçava e dormia a sesta, e pelas 4,00 horas retomava a batalha quotidiana que só terminava por volta das 8,00 da noite.

Uma vivência orgânica, não muito diferente da do campo! À devida hora vinha à porta o pão e o peixe fresco; iam às compras os empregados domésticos, que se prezavam de ser íntegros, temendo não tanto a polícia como a Deus! O trânsito era ligeiro – motocicletas, bicicletas, até carroças, e automóveis, do popular Volkswagen ao luxuoso Cadillac. Estes eram os últimos abencerragens da bonança que resultara, paradoxalmente, do Bloqueio Económico de 1955, e ora simbolizavam o nosso cosmopolitismo.

Disse um escritor japonês que Pangim era a “most unIndian of all Indian cities.” Referia-se certamente à tradicional arquitectura indo-portuguesa, desprovida de arranha-céus e da imundície e do caos que caracterizavam os centros urbanos do subcontinente. Mas teria ele dado conta da arquitectura espiritual do povo? Este não era de grandes ambições e vivia numa mediania. O roubo era raro, e raríssimo o homicídio ou o suicídio. Não havia indícios de sectarismo ou de violência, pois reinava a consciência e a benevolência, ou aquilo a que chamamos munisponn: se à porta humildemente batesse alguém, sentava-se à mesa com a gente – como canta o fado; e no conforto pobrezinho do lar havia fartura de carinho, e bastava pouco para alegrar a existência do citadino.

Pois é, a cidadezinha daquela época tinha um só diário em português (O Heraldo) e em inglês (The Navhind Times); uma só emissora (a All India Radio); um só salão (o do Instituto Menezes Bragança), onde actuava a única academia de música; um único hotel de categoria (o histórico Mandovi); uma só loja de gelados (o Esquimó); um só restaurante sul-indiano (o Shanbhag); um único hospital geral (o da Escola Médica); um único cine-teatro (o Nacional); uma só livraria (a Singbal); uma única biblioteca de fôlego (a Central); uma só grande praça pública (o Azad Maidan); um só campo de jogos público (no Campal); um só amplo jardim (o Garcia de Orta), onde, à tarde, convergiam crianças e adultos, ficando aqueles a saltitar pelos canteiros e estes a conversar amenamente num canto.

Desse jardim guardo várias memórias: a da música executada no seu artístico coreto e a dos slogans – “Tujem mot konnank? – Don panank!” – que eu ingenuamente gritava, nas vésperas do Opinion Poll, em 1967. Lembro-me dos cafés e bares em redor e do jornal em cuja Redacção se ouvia um aflitivo dize-tu-direi-eu, nem por isso resolvendo os problemas da carestia e escassez, da pobreza e embriaguez, estas comuns, por sinal, no bairro pitorescamente denominado Tambddi Mati (Terra Vermelha), tanto por falta de asfalto nas ruelas como pelas lampadazinhas vermelhas nos alpendres!

Enfim, Pangim não era nenhum jardim de virtudes. Até pensara em mudar de cidade, por não suportar a insularidade e me sentir everybody’s business; mas em vez disso mudei de ideia, por recear que entretanto a cidade da minha infância se transformasse num pequeno Bombaim, e nós, em nobody’s business! Mas não havia remédio; a cidade estava já em franca expansão: as casas cediam o lugar a blocos de apartamentos; era construída uma ponte sobre o Mandovi e uma praça de automóveis no pântano do Pattó. Por outro lado, estava incompleta a rede de esgotos; havia falhas na electricidade, e era racionada a água canalizada. O ar era puro; mas ai que, na monção, Pangim de repente era Veneza!...

Ora, fui aprendendo a amar a cidade e a gente. Éramos poucos, éramos irmãos – e saudáveis as relações entre os vizinhos, independentemente dos seus credos. Naqueles tempos, os cavalheiros tiravam o chapéu às senhoras e paravam para dois dedos de conversa! Os baptizados, aniversários e funerais eram eventos de vulto. Não havia televisão; para dissolver o tédio bastava um passeio pela praia do Miramar ou de goddia-gaddi até ao Campal, ao pôr-do-sol. O arraial nas Fontaínhas, o desfile do Carnaval e os bailes nos clubes Nacional e Vasco da Gama vinham a seu tempo. Dir-se-ia o mesmo da Via Sacra; da procissão das velas que do Paço Patriarcal descia até ao ex-libris da igreja matriz; e das novenas e festas religiosas. De tudo isso nascia o espírito de família e a alegria de viver em Pangim.

No afrouxar forçado dos meses da covid-19, voltei a descobrir o rosto da minha cidade. Se em tempos nos faltavam coisas que os outros tinham em abundância, hoje, sentindo novamente aquela calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro, vejo que nos não faltara nada…. Não admira, pois, que Pangim tivesse sido sempre a menina dos olhos de todos os que se prezavam de ser goeses!

Foto de Pangim, gentilmente cedida por Willy Goes

Publicado na secção portuguesa do magazine dominical do diário Herald

Our ancestors respected nature and lived in harmony with it!

September 26, 2020Mangroves,Western Ghats,Aguada sand bar,Ria Formosa,Coastal Regulation Zone,NIO,Tata Energy and Resources Institute,Sand dunes,Dune-beach ecosystem,River Mandovi,Tsunami,CRZ,Miramar,Khazan lands,National Institute of Oceanography,TERIInterview,Environment

“Our ancestors were more sensible. They respected nature and lived in harmony with it,” says Scientist António Mascarenhas, formerly of National Institute of Oceanography, Goa, while assessing the state of the Goan environment, in an interview with Óscar de Noronha.

For original interview in Portuguese

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BvDOm45GCQ&t=759s

O.N. – What are the issues afflicting Goa's natural environment at this time?

A.M. – There are several issues, right from our forest heritage to more serious ones, such as the improper exploitation of our mining resources, the levelling of khazans (wetlands) to build housing complexes; the contamination of our rivers – and now also the attempt to nationalize them, and so on. But to me, the conservation of the dune-beach ecosystems is the most serious issue that exists.

O.N. – What’s the reason for that?

A.M. – Well, any human action on the landscape results in two types of impacts: reversible or irreversible. Now, the disappearance of the frontal dunes causes the beach to recede, making the coastline much more vulnerable to the action of the sea.

O.N. – So, in order to properly address the environmental status of our territory, we must qualify these matters, mustn’t we?

A.M. – For sure! Google Earth shows where Goa stands! Let’s, then, do a fly-by, say from our beaches to the Western Ghats, across the khazans that are our rice paddy fields. We will see the kind of impact that the different areas of the territory have suffered. For example, if a forest is destroyed, the system can be rejuvenated; and a contaminated river can be oxygenated; even khazans converted into a housing area is recoverable. But the destruction of the coast is almost always irreversible.

O.N. – What examples do you have of this in Goa?

A.M. – Well, in Sinquerim and Candolim, the beach retreated due the impact of the River Princess ship that was stuck there for twelve long years! The dunes were flattened also to make place for hotels and residences. The fact is that the dunes do not get replenished easily; sometimes the sand takes decades to come back. Of course, to speed up the process, the beach can be nourished, by filling up the affected parts with new sand. This process also occurs naturally during the period after the monsoon, between September and March. For example, in Baga, Morjim and Querim, a sandy tip is formed. The tip is caused by the sand transported by the coastal current that enters the river or estuary, and is then pushed counterclockwise by the sea. Further north, the dunes disappeared to make way for shacks, with the exception of Mandrem, Morjim and Galgibaga…

O.N. – The case of Galgibaga, in the taluka of Canacona, is different, isn't it?

A.M. – Yes. This area is protected by the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) law, and is considered a breeding ground for turtles, one of the four sites in Goa. Hence, urban development in this place is completely forbidden. And thus the beach has remained well preserved. But on those dunes, there are small little houses that function as restaurants. The National Green Tribunal has ordered their demolition.

O.N. – As far as I know, the dune protection in Miramar was one of the first environmental campaigns that you undertook, in 2007, well over a decade ago...

A.M. – That's right. I was part of the Goa Coastal Zone Management Authority, and am at present a member of the Goa Biodiversity Board. One of the projects we proposed was to save these frontal dunes. Some sites have been indicated where you can replicate that experience of dune reconstruction. Miramar beach is already being considered for this.

And talking of Miramar: here you find a semi-circular sand deposit, in the form of a sand bar, perhaps one of the few its kind in the world. It accretes and gets washed out, and then the sand comes back during the monsoon. It is an annual phenomenon and has been going on for centuries. The feast of the church of St. Lawrence, on the Sinquerim hilltop, from where you can see the silting, coincides with the opening of the sand bar…. I don’t know the connection.

O.N. – That was one reason why Albuquerque had to wait until the end of the monsoon to win Goa back... Here we see a connection between a natural phenomenon and a historical occurrence….!

A.M. – That's right. There is that 'tongue of sand’ at the site, now known as the Aguada sandbar. Here the navigation channel is very narrow and, after the monsoon, it opens up naturally. Unfortunately, the authorities are thinking of dredging the channel, and that’s going to be a real tragedy. Scientist C. S. Murthy has described the functioning of this area. The currents go south to north while on the other side they flow from north to south. On the coast, the currents run from south to north, from Caranzalem to Miramar; and from north to south, from Campal to Miramar. This process is responsible for the formation of the tongue of sand in Miramar. During the monsoon, when the waves caused by the winds from the west reach Miramar, they cause sand erosion; and later, when the good weather returns, the currents get normalized, helping to rejuvenate the beach. This has been an annual process noticed for decades.

O.N. – And does that protect the coast?

A.M. – Well, it was wrongly assumed that the coast would be protected with the construction of a barrier or wall made of large basalt stones brought perhaps from Maharashtra. But this wall has caused the beach to disappear and today we only have those stones left there. This human action on the beach has had consequences just in front of the old Medical School. The Campal stream flows out here. At this point a sandbar has emerged, blocking the passage of the said stream.

O.N. – By and large, is the ecology of the capital city at risk?

A.M. – The danger is not of very great proportions but it is also not something that can be ignored. For example, saline water enters and flows up to where the Fire Brigade is currently located. Despite this, there are many who have an interest in reducing the status of the stream to that of a nullah, a mere drain. The geological maps of the Survey of India of 1965 prove that there is movement of the tidal waters. Therefore, the stream is comes under the purview of special laws relating to the preservation of coastal zones. On the other hand, if it is reduced to the status of nullah, the said area will be outside the scope of those laws.

O.N. – There was destruction of the dunes when the area of Caranzalém was urbanized... What irreversible effects are we witnessing today?

A.M. – Well, in the 1990s the Caranzalém swamps began to disappear, which today are the largest urban area located in the wetlands in Goa. Before this, in the 1970s, the largest area that suffered destruction was where the bus terminus of the capital is located. Today, the high-rise buildings there have their foundations as though floating in the groundwater. These waters are now contaminated. All the wells in the city suburbs have no potable water – whereas I have a fresh-water well at my house in the village of Raia.

O.N. – And for that matter, what is your say on the Mandovi, which is the hope of salvation not only for the capital but also for the territory?

A.M. – It so happens that the neighbouring state Karnataka, where the Mandovi is born, has been trying to divert the water at the very source. The case is in court. Meanwhile, today, Mandovi's condition is nowhere near the same as that of Delhi's Yamuna or Bangalore's Ulsoor Lake. It is less oxygenated but, fortunately, not only does the monsoon refresh the river but also its connection to the sea neutralizes all harmful influences.

O.N. – You have been a scientist at the National Institute of Oceanography... What is the relationship between oceanography and the ecology of the hinterland?

A.M. – Let me explain: The oceans are controlled by the tides twice a day. The water levels rise and fall. The same happens in rivers. In Goa, the impact of the sea is felt up to the remote village of Savoi Verem, in the taluka of Ponda, and up to the village of Macazana of the taluka of Salcete there is appreciable amplitude of tides and saline influx. So, the ocean is connected with the smallest stream. This is confirmed by mangroves, which indicate the presence of saline water. In fact, the area that goes from Cortalim to Macazana, passing through Curtorim and Rachol, has large mangrove swamps. The same can be said of the area between Carambolim and Agaçaim, passing through Azossim, Mandur and Neura.

O.N. – Which is the regulatory authority for wetlands?

A.M. – Well, it is interesting to note that all khazans belong to our Comunidades (agricultural communities). But presently the recently formed Wetland Authority of Goa is in charge. The khazans function as reserves of drinking water. Hence it is essential that our Comunidades are aware of the issues and assert themselves.

O.N. – It seems that the mangroves have helped to afforest the territory…

A.M. – That's right. But this too has to be controlled because mangroves are "colonizers". For example, in Panjim, a mangrove has appeared in an area that was traditionally a salt pan. Likewise, the floodplains at lower levels are now invaded by these trees; and this prevents farmers from cultivating the fields.... These mangroves have engulfed the Linhares Bridge from Panjim to Ribandar and are thus destroying the identity of the historic bridge. And to complicate matters further, there is a garbage treatment plant in the middle of the same mangrove lagoon. These are matters that call for attention.

O.N. – You are a recipient of the ‘Green Heroes’ award from TERI (Tata Energy and Resources Institute), New Delhi. You write regularly for the newspapers, popularizing many of the subjects we’ve talked about today… Is the level of public participation in these matters something that satisfies you?

A.M. – I’m neither satisfied nor frustrated. For 36 years I worked at the National Institute of Oceanography in Goa, a public funded organization. Salaries are paid by the Public Exchequer; hence my primary duty is to meet the needs of society in general and, in particular, to contribute to the conservation of nature.

Of course, public participation in these matters could have and should have been better.... We have the obligation to know the functioning of natural ecosystems: the functioning of the coast and the hills that are found in the hinterland. But it seems that today we suffer from information overload. There are many who do not read, there are others who read but do nothing, and only a few who do act proactively.

But the important thing is that to have proper planning and coordination between the authorities. To manage these issues, a cross-sectoral approach is indispensable. And there should be no politicking. The whole matter must be treated as a sacred cow: the mangroves, dunes, marshes, tidal areas, beaches are all sacred. They are exclusively under the responsibility of Coastal Regulation Zone I (CRZ I), but there have been deviations, there have been transgressions…

O.N. – You’ve travelled through Europe. What initiatives have you noticed?

A.M. – For example, in 2007, I visited the University of Algarve, as a fellow of Fundação Oriente. The sand dune systems there have been recreated. On the beach of Tavira, in a part of the marsh called Ria Formosa, there are now long dune areas; these have been artificially reconstituted but work naturally. Some wooden bridges have also been built that help visitors move to the beach without trampling the frontal dune. Faro beach is a good example of conservation of the fore dunes.

We have similar examples In France. The beach nourishment technique is employed for sand restoration purposes, and this controls erosion. Also erection of wooden fences blocks wind borne sand; and over time these sandy deposits become the frontal dunes.

That's precisely what we propose for Miramar Beach. Well, it also helps to have plantations on the dunes: they help stabilize the dunes.

O.N. – It is obvious that much depends on the political will and public participation in safeguarding our heritage...

A.M. – Yes, there’s no doubt about that. I would be happy if the authorities and the general public were convinced of the great importance of the conservation of natural systems, in particular the coastal area, our beaches and the dunes. These are the first line of defence against the incursions of the sea. If we save the dunes, the population will be saved in the event of an attack from the sea. The tsunami of the year 2004, which devastated parts of Tamil Nadu, has already proven this theory right. I always say that the population was decimated not by the tsunami but by our recklessness in provoking the forces of nature, with construction of urban structures in inappropriate places. In this respect, our ancestors were more sensible. They respected nature and lived hand in hand with it. Thus, from Canacona to Pernem, they were always safe and sound.

O.N. – Well, it was a pleasure talking to you. Thank you for the panoramic view that you gave us on a topic of great importance to our beloved Goa. Thank you.

A.M. – Thank you! Thank you very much!

(First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, II Serie, N.º 6, Set.º-Out.º de 2020)

https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:80665fef-61a8-44bb-988a-e697ace84c22

As realidades da nossa identidade

September 15, 2020Revista da Casa de GoaCulture,Goa

As minhas primeiras palavras são de agradecimento pelo honroso convite que me foi feito de integrar o conselho editorial desta dinâmica Revista, e de saudações aos leitores. Aceitei-o de bom grado por se tratar de um elenco de obreiros culturais com quem doravante poderei colaborar mais estreitamente. E, pela obra feita, os meus parabéns e votos de longa vida à Casa e à sua Direcção.

Para além desses laços que me unem à Revista da Casa de Goa, é a própria terra e cultura de Goa que me acenam. Vivo no meu torrão natal, porém, não pretendo conhecê-lo melhor do que outros que não têm esse ensejo. E nem se pode dizer que os que se ausentam por força das circunstâncias têm menos amor à terra dos seus antepassados. No nosso caso, o que vale é ter o coração sempre a bater por Goa.

Mais. Não é somente o sangue que determina a cidadania cultural. Goa, que conheceu outros povos e culturas, poderia comprovar que no decurso da sua longa história foram muitos que se apaixonaram por ela. Ainda hoje, há pessoas que têm um enternecedor amor, dir-se-ia mesmo uma ligação espiritual com ela. A nós cumpre enaltecer e perpetuar o que há de nobre nesse talismã que se chama Goa.

Podemos dizer, sem receio de errar, que Goa é ao mesmo tempo terra e estado de espírito. E quem somos nós? Na feliz frase de António Colaço, “somos uma pequena e grande família. Não há aqui hindus, moiros ou cristãos. Há só Goeses”. Importa salvaguardar a nossa irmandade, deixando-a viva tanto em Goa como em Lisboa, enfim, em todos os lugares onde se encontram os Goeses, desde os tradicionais kulls ou clubes nas metrópoles indianas até às associações culturais e desportivas dos goeses espalhados pelo mundo.

Neste particular, devem Goa e Lisboa assumir um papel de liderança. Essa liderança se impõe pelo facto de serem elas os pilares da universal Casa e Espírito de Goa. Graças a Lisboa, a minúscula Goa foi em tempos o ponto de encontro do Oriente e Ocidente: aí se fundiram as culturas lusa e indiana; aí dois mundos se trocaram; aí se deu aquilo que Gilberto Freyre designou de “milagre sociológico”. Goa e Lisboa foram mesmo precursores da globalização.

Fica assim bem clara a acção pioneira que tiveram Goa e Lisboa no conhecimento mútuo das sociedades e culturas. Em ambas as cidades o elemento local se tornou universal, e vice-versa. Como agentes de transformação dos povos que mal se conheciam; como modelos de paz e amor fraterno, Goa e Lisboa têm os seus nomes escritos em letras douradas. Só que jamais se pode falar de amchém bhangarachém Goem – “nossa Goa dourada” – nem Lisboa se pode gabar de capital cultural sem problemas.

Nessas voltas que o mundo dá, festejemos a nossa identidade, cantando os louvores à língua e literatura, música e arquitectura, indumentária e culinária, às nossas seculares instituições e tradições, mas reconheçamos também as novas realidades…. Aquilo a que chamamos Goa, existe ela na realidade, ou é uma simple miragem? Se existe, até quando será ela goesa? E esse espírito, estaria ele claro ou cada vez mais nebuloso?

Nesse sentido, urge uma conscientização e relevante acção. Consistiria em viver com amor ao torrão natal; valorizar o seu património; salvar o meio ambiente; cultivar as terras com engenho e alegria; e acima de tudo, participar activa e patrioticamente na governação, com plena consciência dos valores subjacentes à cultura goesa.

Nesta Revista e noutros lugares, enquanto delineamos o nosso ideal, trabalhemos com os corações unidos em volta desta louvável causa comum.

(Editorial na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Serie, N.º 6, Set.º-Out.º de 2020)

https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:80665fef-61a8-44bb-988a-e697ace84c22

On my first blogiversary…

August 15, 2020First blogiversary,Lemon Tart Media,Ian de NoronhaBlogiversary

For me, it was a dream come true. So here goes a big thank-you to my nephew Ian and his Lemon Tart Media, for putting the website together; and to my readers, for being a significant part of it through my first blogyear.

A blog allows you the joyous freedom to write to your heart’s content. It’s a great proposition for those who like to write, or better, feel the need to write, express their views and communicate with a larger audience.

But a blog is nothing without its readers. Thankfully, I’ve had the privilege of connecting with cyberpeople from far and wide. By and by, we will be leaving behind a long trail of digital timestamps….

That’s a far cry from when it all began, forty years ago! I still remember the goose bumps I got on seeing my name in print for the first time. And recently, when I filed my maiden piece here, it felt as if I was holding the crisp issue of that morning’s newspaper in my hands!

The versatility of a website is heartening. As you can see, mine has not only served as an archive for my pre-blog, published writings; it has given my audios of three decades ago a new lease of life. Do check all that out, together with those of my social media posts that now enjoy permanent resident status here.

All in all, I am delighted to have this opportunity to look back and move forward. While I hope my trip down memory lane kindles your very own sweet recollections, I also look forward to your esteemed company along new paths and new tomorrows.

Thanks a million!

Vaz, Montfort and their self-consecrations

August 5, 2020Of Divine Bondage,Sri Lanka,St Louis de Montfort,France,Treatise on the True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin,Goa,Deed of Bondage,Sancoale,St Joseph Vaz,Love of Eternal WisdomMarian Devotion

Marian dedication stands enriched by the singular contributions made by Joseph Vaz (Goa, 1651 – Sri Lanka, 1711) and Louis de Montfort (France, 1673 – France, 1716).

Vazian Formula

Joseph Vaz expressed his profound love and tender care to the sublime Queen of the Universe and Mother of Fair Love in a memorable document known as the “Deed of Bondage”,[1] which reads as follows:

Be it known to all who see this deed of bondage, the angels, men, and all creatures, that I, Father Joseph Vaz, sell and offer myself as a perpetual slave of the Virgin Mother of God, through a free, spontaneous and perfect gift that in law is said to be irrevocable inter vivos; I give myself and my assets that she, as my true Lady, may dispose of me and of them according to her will; and as I consider myself unworthy of such an honour, I beseech my Guardian Angel and the glorious Patriarch St Joseph, most beloved Spouse of this Sovereign Lady and saint of my name, and other citizens of heaven, to ensure that she includes me in the number of Her slaves. In witness thereof I seal this with my name, and would have liked to seal it with the blood of my heart. Written at the Church of Sancoale, at the foot of the altar of the same Virgin Mary Mother of God, Our Lady of Health, this fifth day of August, Feast of Our Lady of the Snows, one thousand six hundred and seventy-seven. – Joseph Vaz.[2]

In Goa, the consecration has been traditionally looked at as something peculiar to St Joseph Vaz. The original “Deed” is not traceable, but Joseph Vaz’s first published biographer, the Oratorian priest Sebastião do Rego (1699-?), vouches that he read and kissed it several times, in the hope that he would be touched by a spark of the great fire with which it was written.[3] Did the Saint leave the manuscript behind with the Congregation, or with his family, in Goa? Might he have carried it with him to Sri Lanka? Hopefully, it will one day be found among the Oratorian documents.

What might have inspired Joseph Vaz to commit himself thus to our Divine Mother? Was it the influence of a teacher, from among the Jesuits, or more likely from among the Dominicans, who are known to have been great Marian devotees? Did Joseph find motivation in the books of spirituality that he came across in the rich seminary libraries? Further, why did he take the Feast of Our Lady of the Snows for a red-letter day in his life? Was it the fact that she is the patroness of Rome’s most important Marian church popularly called Santa Maria Maggiore?

While answers to those questions may remain conjectural, one thing is sure: what the Apostle of Sri Lanka has bequeathed to humankind is a precious document with a tenor both mystical and direct; it is “a unique deed inter vivos, in which Fr. Joseph Vaz is at once the donor and donation, notary and clerk; and the Blessed Virgin, donee and witness, while the Patriarch St Joseph, Spouse of the Donee and his namesake, his guardian angel and the other citizens of heaven are constituted intercessors before the Donee”.[4] Joseph Vaz is ready, Christ-like, to shed blood in atonement. And far from alienating the reader, the legalese underscores the solemnity of the act.

Montfortian Formula

Coming to Montfort’s act of consecration: it is the grand finale to his Treatise on the True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin.[5] His formula, thrice as long as Vaz’s, reads as follows:

O Eternal and Incarnate Wisdom! O sweetest and most adorable Jesus! True God and true man, only Son of the Eternal Father, and of Mary, always virgin! I adore Thee profoundly in the bosom and splendours of Thy Father during eternity; and I adore Thee also in the virginal bosom of Mary, Thy most worthy Mother, in the time of Thine incarnation.

I give Thee thanks for that Thou hast annihilated Thyself, taking the form of a slave in order to rescue me from the cruel slavery of the devil. I praise and glorify Thee for that Thou hast been pleased to submit Thyself to Mary, Thy holy Mother, in all things, in order to make me Thy faithful slave through her. But, alas! Ungrateful and faithless as I have been, I have not kept the promises which I made so solemnly to Thee in my Baptism; I have not fulfilled my obligations; I do not deserve to be called Thy child, nor yet Thy slave; and as there is nothing in me which does not merit Thine anger and Thy repulse, I dare not come by myself before Thy most holy and august Majesty. It is on this account that I have recourse to the intercession of Thy most holy Mother, whom Thou hast given me for a mediatrix with Thee. It is through her that I hope to obtain of Thee contrition, the pardon of my sins, and the acquisition and preservation of wisdom.

Hail, then, O immaculate Mary, living tabernacle of the Divinity, where the Eternal Wisdom willed to be hidden and to be adored by angels and by men! Hail, O Queen of Heaven and earth, to whose empire everything is subject which is under God. Hail, O sure refuge of sinners, whose mercy fails no one. Hear the desires which I have of the Divine Wisdom; and for that end receive the vows and offerings which in my lowliness I present to thee.

I, N_____, a faithless sinner, renew and ratify today in thy hands the vows of my Baptism; I renounce forever Satan, his pomps and works; and I give myself entirely to Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Wisdom, to carry my cross after Him all the days of my life, and to be more faithful to Him than I have ever been before. In the presence of all the heavenly court I choose thee this day for my Mother and Mistress. I deliver and consecrate to thee, as thy slave, my body and soul, my goods, both interior and exterior, and even the value of all my good actions, past, present and future; leaving to thee the entire and full right of disposing of me, and all that belongs to me, without exception, according to thy good pleasure, for the greater glory of God in time and in eternity.

Receive, O benignant Virgin, this little offering of my slavery, in honour of, and in union with, that subjection which the Eternal Wisdom deigned to have to thy maternity; in homage to the power which both of you have over this poor sinner, and in thanksgiving for the privileges with which the Holy Trinity has favoured thee. I declare that I wish henceforth, as thy true slave, to seek thy honour and to obey thee in all things.

O admirable Mother, present me to thy dear Son as His eternal slave, so that as He has redeemed me by thee, by thee He may receive me! O Mother of mercy, grant me the grace to obtain the true Wisdom of God; and for that end receive me among those whom thou lovest and teachest, whom thou leadest, nourishest and protectest as thy children and thy slaves.

O faithful Virgin, make me in all things so perfect a disciple, imitator and slave of the Incarnate Wisdom, Jesus Christ thy Son, that I may attain, by thine intercession and by thine example, to the fullness of His age on earth and of His glory in Heaven. Amen.

Montfort’s formula begins with an invocation of the Incarnate God. The Christological opening is quickly followed by Marian veneration, in acknowledgment of the Incarnation. Our Lord’s death on the Cross is an act of incomparable nobility, yearning as He did to rescue humanity through His sacrifice; our inspired author stresses that He emptied himself, taking the form of a slave (Phil. 2:7). A self-imposed slavery like this can only be termed a slavery of love.

Montfort points to a divine enslavement that is liberating, as opposed to human liberty that can be enslaving. And what can be better than following Jesus’ example of submitting Himself to His holy Mother? At the heart of the Montfortian formula is the recognition of human unworthiness to stand in the presence of our Lord and God, other than through His Mother’s intercession. The point of resolution comes with the renewal of the baptismal vows; an express renunciation of Satan; and decision to follow Jesus and be faithful to Him.

Appraisal

The two consecration formulas are essentially the same: note the similarity of the terms employed. In addition, Vaz sells himself as a slave while offering himself as a “gift in perpetuity”; he humbly calls upon the angels, men and creatures, to mediate, for is it not perfectly justified to take one’s Guardian Angel into confidence; to appeal to the saint of one’s name; and, as per the communion of saints, invoke their intercession before her.

Vaz’s act is crisp and intimate; Montfort’s, uninhibited and elaborate. St Joseph Vaz’s singular self-offering happened when he was 26 years of age; it is not known when St Louis de Montfort made his, but he included a very brief formula of consecration at the end of his Love of Eternal Wisdom (c. 1703), when he was 30. Vaz embraced the spirituality of St Philip Neri eight years after his consecration; Montfort became a Dominican tertiary in 1710, three years before his Treatise.

Finally, Fr. Joseph Vaz is not known to have ever spoken publicly about his “Deed”, so it may be regarded as a very personal statement. It was for sure a product of his deep conviction; none before him are known to have embraced the slavery of love in Goa,[6] and none from among his confreres are known to have followed his example. On the other hand, not only is Montfort’s Treatise highly elucidative, his consecration formula is an expansive public declaration of what every Catholic ought to strive for; it is a standing invitation to build a profound and intimate union with Christ through Mary.

(Excerpted from my article titled “Two Saints and a Consecration for our Times”, in St Joseph Vaz for All Times, edited by Fr. Aleixo Menezes and published by the Archdiocese of Goa and Daman, 2015, and posted here with minor alterations)

[1] This is sometimes referred to as a “Letter”, in a literal translation of the Portuguese “Carta do Cativeiro”. Whereas “Cativeiro” could be variably translated as captivity, bondage, or slavery; “Carta” would be better translated as “Deed”, and not simply as “Letter”, particularly considering the legal language in which it is couched.

[2] Translated by this author. Cf. Óscar DE NORONHA, Of Divine Bondage: The Epic Life of St Joseph Vaz, (Third Millennium: Panjim, 2014), 25

[3] Sebastião DO REGO, Vida do Venerável Padre José Vaz (Imprensa Nacional: Goa, 19623), 172.

[4] Seráfico MISQUITA, Ven. Padre José Vaz, Apóstolo de Ceilão (Tipografia Rangel: Goa, 1969), 30.

[5] St Louis DE MONTFORT, True Devotion to Mary. Transl. Frederick William Faber. Revised edition. (Montfort Publications: New York, 1967), 227-229.

[6] St Louis de Montfort himself has said that although the true devotion is an easy way, few saints have entered upon it. Cf. James Patrick GAFFNEY, ed., Jesus Living in Mary, op. cit., 231.

The Curé of Ars: a Fool for Christ

August 4, 2020St Jean-Baptiste Marie Vianney,Little Catechism of the Curé of Ars,Ars,Chesterton,St John Vianney,Curé of Ars,Père Gratry,French RevolutionSaints

Some thirty years ago, I was touched by The Little Catechism of the Curé of Ars. The book contained select passages from the sermons and writings of one who had scraped through the seminary but ended up teaching even exalted churchmen. The book comprised his sage counsel on thirty-six important topics – Catholic wisdom stated in a simple, sublime, penetrating way.

Some thirty years ago, I was touched by The Little Catechism of the Curé of Ars. The book contained select passages from the sermons and writings of one who had scraped through the seminary but ended up teaching even exalted churchmen. The book comprised his sage counsel on thirty-six important topics – Catholic wisdom stated in a simple, sublime, penetrating way.

Amazing Life

I was simply curious to know about the life of this spinner of divine tales. He was none other than St Jean-Baptiste-Marie Vianney (1786-1859), a modest priest who transformed Ars, a non-descript parish in France, into a spiritual hub, thanks to his soothing confessions and zealous preaching.

Vianney was a born in a revolutionary age but spurned the revolution. In the face of the anticlerical sentiment of the Reign of Terror in France, he got to make his first communion and confession only at 11 years of age. Meanwhile, the heroism of the priests and nuns who had risked their lives for their faith impressed him. He felt a strong call that to pursue the priesthood but struggled with his theological studies. In 1815, he was finally ordained “though compassion”.

In 1818 he was appointed to Ars. The simple priesthood he exercised there, guided by prayer, fasting and penance, changed the village and infected the world with reports of his holiness. He was devoted to the Blessed Virgin Mary and to St Philomena. Most dedicated to the sacraments of the Holy Eucharist and Penance, he spent hours and hours before the Blessed Sacrament and in the confessional.

Always in awe of the priesthood, he said, “If I were to meet a priest and an angel, I would first greet the priest and then the angel… If there were no priest, the passion and death of Jesus would serve no purpose. What use is a treasure chest full of gold if there is no one who can unlock it? The priest has the key to the treasures of Heaven.”

By 1827 Ars had become a pilgrimage site, and, from 1845 until Vianney’s death in 1859, thousands from all stations of life visited that model parish to hear his preaching, make their confession, and be counselled by him. Pope Pius XI canonised him in 1925 and later declared him Patron of the Parish Priests. His body lies incorrupt and preserved in a glass coffin in the basilica of Ars.

Secret Hour

Somehow, I can’t help thinking of Chesterton’s “Donkey”. Prizing his unique encounter with Christ in Jerusalem, this beast of burden quietly thought of all those who despised him as mere “Fools! For I also had my hour, One far fierce hour and sweet…”

Likewise, Vianney had only his priesthood to offer and wouldn’t trade it for the world. He lived it intensely to the point that he became an alter Christus. The spirit of God was engraved in his heart. His faith was his knowledge, which he sought not in libraries or amidst the learned, but solely by falling on his knees in prayer.

Thereafter there was no stopping him. His prayer flowed through his preaching. They say it was difficult to listen to him and be unmoved, because he preached with his whole being – to packed pews yet to each heart, and as though scanning every secret history. He spoke colloquial French, sometimes grammatically incorrect, yet the congregation got a foretaste of heaven. Mingling with his discourses some happy reminiscences of his shepherd life, he borrowed his similes and metaphors from nature, from the beauties of the country and the emotions of rural life. No wonder, men and women living in a troubled world experienced the peace of God’s word.

But that was not all. A spiritual cure would never be complete without a heartfelt confession, for the Lord never spurns a humble, contrite heart. Here was a Curé, a contemplative who softened the austerity of his ideas through poetic images. His life was restricted to the little world of Ars but his reflections on topical issues touched those who came from far and wide seeking his help. The pastor’s thoughts were deep and sometimes startling enough to stop the penitent in his tracks. For instance, he called the cemetery the home of all; purgatory, the infirmary of the good God; and earth, a warehouse. And he said, very categorically, that a soul after confession requires tears to purify it.

What a fool!

I confess with nostalgia that it is in the Little Catechism of the Curé of Ars that I first encountered the term “infused science”. This refers to knowledge divinely conferred on human beings without previous experience or reflection. Or, according to Père Gratry, who is quoted in the preface: “There is no doubt that, through purity of heart, innocence, either preserved or recovered by virtue, faith, and religion, there are in man capabilities and resources of mind, of body, and of heart which most people would not suspect. To this order of resources belongs what theology calls infused science, the intellectual virtues which the Divine Word inspires into our minds when He dwells in us by faith and love.”

When I first read Vianney, it struck me that wise fools are they who are anointed by the Lord with an infused science that makes all things possible. In the words of St Paul, “We are fools for Christ's sake, but you are wise in Christ.” (1 Cor 4: 10)

A Última Conversa com Percival Noronha

July 26, 2020Revista da Casa de Goa,Dezembro de 1961,Fontaínhas,Ordem de Mérito,Pangim,Association of Friends of Astronomy,Fundação Oriente,Vassalo e Silva,Indian Heritage Society,Renascença Goa,“Um Goês Exemplar”,Salazar,Museu da Arte Cristã,INTACH,António dos Mártires Lopes,Goa,Velha Cidade de GoaPersonality

Numa tarde chuvosa (1 de Julho do ano passado), quando de súbito me lembrei do Sr. Percival Noronha[1], não hesitei em terminar a minha sesta dominical. Um distinto cavalheiro – culto, agradável, e que me estimava – daí a dias iria completar a bonita idade de 95 anos… Urgia, pois, falar com o grand old man de Pangim.

Quando liguei para a sua casa, ouvi logo um ‘Estou!’ inconfundível. Na linguagem do Sr. Percival, esse estar era o mesmo que estar disponível! ‘Pode o Óscar vir quando quiser’, disse com a amabilidade que o caracterizava. Estava sempre pronto para um papo, e desta vez seria como nunca dantes: radiodifundida na minha rubrica mensal, Renascença Goa… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRK2PimgTmo) Saí então rumo às Fontaínhas, acompanhado do meu irmão Orlando que trataria das fotos.

Era um prazer ir à residência do Sr. Percival (‘Ajenor’, nº E-426, à Rua Cunha Gonçalves). Também nos cruzámos, por centenas de vezes, em concertos, conferências, exposições de arte, e não menos em casamentos e funerais. Um senhor da velha guarda, era cumpridor dos seus deveres sociais e cívicos. Apesar da nossa diferença etária, a conversa corria como um rio de águas claras, pois o Sr. Percival era não só envolvente mas também apreciador dos méritos dos seus contemporâneos e estimulador dos talentos dos mais novos.

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Diga-se de passagem que eu admirava o seu automóvel, preto, parecendo sempre novo, tal como o seu proprietário. Este, sempre vestido de bush shirt ou camisa safari, percorria os cantos e recantos da cidade, que conhecia como a palma da sua mão. É que Percival e Pangim se pertenciam um ao outro: foi dos melhores cronistas da capital, do seu ethos e do seu ritmo, que descreveu em bela prosa.[2] E fê-lo com autoridade, mesmo porque presenciou nove décadas, ou seja, metade da história dessa urbanização,[3], de forma que hoje se torna difícil imaginar o nosso Pangim sem o Sr. Percival Noronha.

Cargos oficiais

Feitos os estudos liceais na capital, o Sr. Percival Noronha entrou para a administração pública, em 1947. Trabalhou, primeiro, nas Obras Públicas, passando depois para os Serviços da Estatística e Informação. Quando esta foi desagregada, o distinto professor e escritor António dos Mártires Lopes levou-o consigo para os novos Serviços de Turismo e Informação de que este acabava de ser nomeado chefe. O Sr. Percival nunca se esqueceu dos belos tempos do Liceu e do funcionalismo que passou sob a alçada directa desse seu antigo professor liceal: confessava que essa relação fora fundamental em nutrir a sua paixão pela história e cultura.

Quando se deu a mudança do regime politico, em Dezembro de 1961, o Sr. Percival era chefe-adjunto dos Serviços da Informação, reportando ao governador-geral Vassalo e Silva. Em Junho de 1980, a visita do simpático governador coincidiu com as comemorações do 4.º centenário da morte de Luís de Camões em Goa. Vinha a título pessoal, mas nem por isso a visita deixou de suscitar controvérsia.

Decorreu-se o pior da cena no Azad Maidan (‘Largo da Liberdade’), a antiga Praça Afonso de Albuquerque. Aqui, à certa distância, vi o antigo governante a ser interpelado por alegados actos de comissão e omissão do regime português em Goa.[4] O embaraçoso incidente atalhou-o o Sr. Percival Noronha, que, na qualidade de chefe de Protocolo do Território de Goa,[5] estava incumbido de acompanhar o ilustre visitante.

Antes dessa data, com a limitada bagagem de conhecimentos de inglês auferidos no Liceu, e língua essa que logo veio a dominar, o Sr. Percival Noronha ocupou outros cargos importantes na administração indiana. Foi sub-secretário das indústrias, minas, trabalho, saúde e turismo. Entre muitas outras iniciativas suas, os hospitais do Asilo em Mapuçá e o Hospício de Margão passaram a subordinar-se à Direcção de Saúde. Desenvolveu as zonas de Calangute, Colvá, Mayém e Farmagudi, e ideou os desfiles do Carnaval e Xigmó; teve papel preponderante no arruamento Campal-Miramar e na arborização do Parque Infantil; e foi um dos responsáveis pela realização da grande Feira Agrícola em 1970. Ora, possuidor dum raro espírito de autocrítica, não ocultava as faltas que houvera no planeamento e execução dessas suas propostas.

Não admira que o Sr. Percival Noronha tivesse sido um solteirão muito cobiçado. Passou, porém, a vida a cuidar da veneranda mãe, vindo a aposentar-se apenas um ano após a sua morte. Era igualmente dedicado à vida burocrática, passando horas a fio à mesa do gabinete, até para além das horas regulamentares. Um funcionário desse quilate podia facilmente esquecer-se de si próprio, como foi, na verdade, o caso do Sr. Percival Noronha.

Vida de aposentado

Teria sido diferente a sua vida depois de aposentado em 1981? Mudou de actividade, sim, mas o expediente não mudou de volume. Dedicou-se, a tempo inteiro, às matérias por que tinha propensão natural: a arte, a história e a astronomia.

Começou por dotar a sua residência com mobiliário de estilo tipicamente indo-português. Efectuou-se grande parte dessa obra no rés-do-chão do seu prédio, o qual havia sido confiado ao conhecido carpinteiro Zó. Disse-me, em mais de uma ocasião, que gastara nisso quase todas as suas economias. Também é verdade que todo dinheiro lhe era pouco quanto se tratasse de comprar objectos de arte e livros.[6] Assim, a casa se viu transformada em verdadeiro museu-arquivo que deveras honra o histórico bairro das Fontaínhas.

O Sr. Percival não parou por aí: tomou a peito vários assuntos de interesse público. Inspirado pelo alto funcionário (e depois governador) K. T. Satarawala, no ano de 1982 abriu um ramo da Indian Heritage Society em Goa e foi professor convidado da Faculdade de Arquitectura. Exerceu o cargo de secretário daquela organização não-governamental que, em colaboração com a Town and Country Planning Department, preparou um relatório sobre os prédios e sítios de importância arquitectónica no território de Goa. Foi também tesoureiro do INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) em Goa.

Esses organismos continua a desempen har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

Embora o Sr. Percival Noronha fosse indiferente em matéria religiosa, nunca hostilizou a Igreja. Pelo contrário, reconhecendo o papel desta no progresso espiritual e material dos povos, colaborou com as entidades eclesiásticas. Em 1986, quando da visita do Papa João Paulo II, participou entusiasticamente na preparação do evento. E, em 1994, foi membro fundador do Museu de Arte Cristã que ora se acha no Convento de S. Mónica.

Esse goês de gema era um arco-íris de saberes, tratando tanto da arqueologia como da astronomia com a mesma facilidade. Fundou a Association of Friends of Astronomy (AFA)[10], em 1982. Este organismo, além de vir a publicar uma revista mensal, Via Lactea, editada pelo fundador, abriu, em 1990, um observatório astronómico público – o primeiro do seu género na Índia – com o apoio do Departamento de Ciência, Tecnologia e Meio-Ambiente, do Estado de Goa.

O Sr. Percival Noronha viveu uma vida sem artifícios – plain living and high thinking. Foi um líder cultural que criou à sua volta uma pleiade de jovens com decidida propensão pela história, arqueologia, arte e astronomia. Na sua casa, onde funcionavam os dois organismos que criou, recebia jornalistas, pesquisadores e outra gente interessada. Teimava em alertar a geração nova sobre o grave estado de bancarrota civilizacional em que a sua amada Goa estava a descambar. Esses recursos humanos e hábitos salutares sendo o maior legado do Sr. Percival Noronha, tem razão a Fundação Oriente em apelidá-lo de “Um Goês Exemplar”, num livro que publicou em sua homenagem.

Na verdade, é a vida intelectual que o entusiasmava, contribuíndo também para a sua saúde física. A sua roda de amigos da velha data[11] nutria a saudade pelo passado enquanto a geração nova o desafiava com projectos futuristas. Era um desses amicus certus, que tratando-se de algum sem-vergonha, falava, tipicamente, com ironia e sorriso escarninho. Mas não vou sem frizar que a todos desejava o bem, e para uma vida saudável recomendava-lhes uma medida de moog grelado por dia! Antes da prótese da anca, em Abril deste ano, esteve relativamente lúcido e ágil.

Última conversa

96 anos da vida. Dir-se-ia mesmo que o Sr. Percival Noronha teve sete vidas. Nos últimos anos era seu costume, quando adoecesse, anunciar a sua morte e daí a dias estar em pé! Era como que tivesse um sistema imunológico como o do gato persa, de que gostava. Não era motivo para recear, pois, quando ouvi de novo que o Amigo estava em declínio. Tive, porém, empenho em conversar com ele demoradamente.

Às 4,30 da tarde, o Sr. Percival tinha já à mesa o bule de chá e bolachas. Dormira a sesta e estava pronto para uma conversa. A rapariga, às ordens, sentada lá no fundo da sala. E parecia tudo como dantes...

Foi quando notei que o venerando ancião tinha o cabelo despenteado, a barba por fazer, e faltava-lhe a placa de dentes. Nunca o vira assim… Os apetrechos de trabalho estavam lá todos, arrumadinhos, nas estantes e armários, dum lado da sala de jantar, onde costumava passar grande parte do tempo a trabalhar. Também isso não estava como dantes... E reflecti também que desta vez o meu anfitrião que viera ele à janela, como era seu costume, deitando para mim a chave da porta principal… Tudo isso indicava que a sua vida ia afrouxando. Fiquei triste.

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

No entanto, ia falando sobre o seu currículo escolar e profissional; as suas actividades depois de aposentado; sobre Salazar (cuja inteligência e honestidade admirava) e o 18/19 de Dezembro; a administração, portuguesa e indiana; os cursos e conferências que realizou nas universidades da Ásia e Europa; o futura da língua portuguesa em Goa; a cultura goesa e a distorção da sua história; os seus amigos e as pessoas que admirava; e a vida em Pangim: tudo isso, entre muitos outros assuntos, e não necessariamente nessa ordem de ideias.

Nos últimos meses, vi-o, várias vezes, debruçado no peitoril da varanda, qual abencerragem a observar a vida que corria lá fora, e com a cara de quem pensa: Quantum mutatis ab illo… Barbudo, lembrava Abraão, personagem de primordial importância para as comunidades à sua volta. E com aquele cabelo a voar e ele a fitar o firmamento, assemelhava-se à figura de Einstein…

Também lá do alto do Céu ouvirá – no último domingo do mês de Novembro deste ano – a última entrevista que concedeu cá na terra. Foi a minha última conversa com o Sr. Percival Noronha.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] De nome completo, Percival Ivo Vital e Noronha (26.7.1923 –19.8.2019), filho de António José de Noronha, de Loutulim, e de Aurora Vital, de S. Matias.

[2] “Panjim: Princess of the Mandovi” (2002); “Fontaínhas: vivendo com o passado”(2001); “Fontaínhas: the Tale of Panjim’s Latin Quarter” (2003), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015)

[3] A vila de Pangim foi elevada à cidade com a denominação de Nova Goa, por alvará de 22 de Março de 1843, o qual lhe outorgou todos os privilégios de que gozavam as cidades de Portugal Continental.

[4] O incidente impulsionou a minha primeira intervenção jornalística em forma de uma carta ao director dum jornal de Pangim – “Our Honoured Guest”, in The Navhind Times, 12/6/1980.

[5] Na altura, cumulava este cargo com o de director da administração das Obras Públicas.

[6] Doou a sua casa ao sobrinho Francisco Lume Pereira, de Verna, onde Percíval Noronha faleceu, e os livros doou-os à Universidade dos Açores e à Krishnadas Shama Library, de Pangim; e os diapositivos, ao Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino.

[7] “Christian Art in Goa” (1993); “Indo-Portuguese Furniture and its Evolution” (2000); “Priceless Christian Art” (2004), e “Goan Artisans” (2008), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[8] “Levantamento arqueológico da Velha Goa e tentativas para a sua conservação” (1989); “Old Goa in the context of Indian heritage”(1997); “Um passeio pela Velha Cidade de Goa”(1999); “A Capela de Nossa Senhora do Monte, em Velha Goa” (2001), ), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[9] Recebeu ao todo 16 galardões de proveniência vária.

[10] http://afagoa.org/about_us.html

[11] Entre outros, António dos Mártires Lopes, Aleixo Manuel da Costa, Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes, Alcina dos Mártires Lopes, Artur Teodoro de Matos, Luís Filipe Thomaz, Teotónio de Souza, Rafael Viegas, Nandakumar Kamat, Satish Naik.

[12] Tradition and Modernity in Eighteenth-Century Goa (Manohar, New Delhi & Centro de HIstória de Além-Mar, Lisboa, 2006)

[13] Old Goa: A Complete Guide (Panjim: Third Millennium, 2004)

[14] Castilho de Noronha: por Deus e pelo País (Panjim, Third Millennium, 2018)

Fotos de Orlando de Noronha, com excepção da da condecoração (e-cultura.pt) e da do lançamento do livro (Fundação Oriente)

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série, Número 1, Maio/Dezembro de 2019 https://issuu.com/jmm47/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n1_-_maio-dez_

What was the Inquisition? - 3

June 29, 2020Inquisition,History

Even though it was a webinar relating to the Goa Inquisition that acted as bait, the purpose of this three-part series has been to study the concept, origin and development of the Inquisition in general, since those who malign it hardly care to understand its rationale.

By way of recapitulation, we could say that, with Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire since the days of Constantine, Church and State worked closely together. Unity of faith was essential not only to the ecclesiastical organization but to civil society. Although both Church and State had their own sets of laws their jurisdictions overlapped at times. Some ancient laws and procedures were Christianised, to the extent that the monarchs consented; the high and mighty had their own ways and very often even overpowered their spiritual head, the Pope.

Ultimately, in the sixteenth century, Church and State reached the tipping point in terms of jurisdiction. Pope Gregory IX decided to shoulder a task that had long been in the secular domain. He instituted a full-fledged inquisition tribunal to conduct official inquiries into heretical behaviour of Catholics, the intention being more reformative than punitive. While the tribunal dealt with what was essentially a spiritual issue, punishment for the recalcitrant remained a domain of the State, considering that heresy was a crime on a par with high treason.

Confused Perspectives

If the Inquisition is a scandal to non-Catholics, an embarrassment to Catholics in particular, and a pretty confusing thing to all, we hope that in tackling the confusion here, some of that scandal and embarrassment too will be resolved.

Behind a state of confusion there often lurks a malicious resolve to confuse. The webinar organised by a national-level Hindu fundamentalist outfit, on 30 May 2020, was a harangue spewing venomous myths to fuel the public imagination. The Upanishadic “Satyameva jayate” (Truth alone triumphs) went out of the window; it may require another series on the Goa Inquisition alone to restore the truth, or we could wait for the panelists to return after some homework.

There is also confusion when history is critiqued from a modern standpoint. As expected, in a post-webinar engagement, a “presentist” decried the Inquisition as a violation of human rights! Well, why just the Inquisition? By our standards, many ancient legal procedures would be dubbed unjust, surgical methods barbaric and disciplinary methods cruel! In the frenzied context of the pulling down of statues, probably every wonder of the world would have to be flattened for failing to measure up to our benchmarks of social justice.

On the other hand, it is interesting to note that even though medieval society did not look at “human rights” the way we do, the natural law discourse was active; it evolved into “natural rights” in the so-called “Age of Enlightenment” and emerged as “human rights” in the twentieth century. Our difficulty in appreciating the evolution shouldn’t make us flag-bearers of ingratitude lest we fail to acknowledge that, under that very same code of ethics, there was progress in art, science, culture and commerce, of which we are beneficiaries.

At any rate, the black legend surrounding the Inquisition is not of recent origin. It began with the Protestant Revolution and continued through the French Revolution and the Liberal revolutions in Europe. Even in the midst of all that radicalism, Voltaire, an arch-enemy of the Catholic Church, had the composure to write: “You have to be very cunning to calumniate the Inquisition, and to look for lies to render it odious.” Protestant authors like Henry Charles Lea and G. G. Coulton probably got most of the facts right but failed to weigh them well, perhaps influenced by prior animosity toward the Catholic Church (though not to the Inquisition itself) and/or overwhelmed by the subject. And somewhat similar was the sensational tale of the Goa Inquisition as told by a culprit (Charles Dellon), full of sound and fury – signifying something, for sure; but generations handled it sloppily, wickedly, and blew it out of proportion.

Artists and philosophers too added fuel to the fire. Some of the confusion surrounding the Inquisition came from their symbolic or fictional accounts. For instance, “St Dominic presiding at an auto da fé”, by the Spanish Pedro Berruguete, showed all stages of the Inquisition as happening at once, as though it were a free-for-all; of Dostoevsky’s poem “The Grand Inquisitor”, in The Brothers Karamazov. The illustrations in Dellon’s book too are fictional and deceptive. Likewise, the large numbers of burnings detailed in some historical accounts are unauthenticated, possibly the invention of pamphleteers.

Needless to say, serious authors across the world have treated the subject of the Inquisition in an unbiased manner, calling the spade a spade; but they haven’t been dramatic enough to garner attention.

Scandalous, is it?

Was the very inquisitorial method a scandal? It is one of the two types of legal traditions that have dominated the nature of investigation and adjudication around the world, the other being the adversarial system. The Church had no option but to follow the Roman Empire’s ‘civil law’ tradition which prescribed the inquisitorial system (as opposed to the ‘common law’ system followed in some other parts of the world).

While in the adversarial system, the prosecution and defence are said to compete against each other, with the judge serving as a referee; the inquisitorial system is characterized by extensive pre-trial investigation and interrogations aimed to avoid bringing an innocent person to trial. The judge here has relatively more powers but he is not ipso facto an enemy of the accused. In fact, with lawyers averse to arguing the case of a heretic, the inquisitor had to steer the collation and prepare the evidence, while all the while coaxing the suspect into owning up and returning to the fold.

The use of torture as a means of obtaining confessions is also contentious. It was generally opposed by the Catholic Church through the Early Middle Ages; however, in the High Middle Ages, the Church, extremely preoccupied as it was with the great threat posed by mushrooming heresies, Catharism in particular, adopted the torture methods employed by the secular governments. Pope Innocent IV, in Bull Ad extirpanda (A.D. 1252), stipulated that the inquisitors were to “stop short of danger to life or limb”; but alas, there was scope for abuses, and the accused could well have endured the torments without admitting anything, or admitted guilt of a crime not committed.

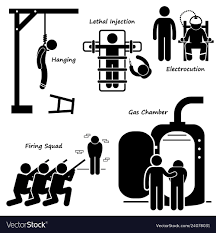

Finally, what of the death penalty and the concurrent confiscation of property? While many learned churchmen had found burning at the stake incompatible with the spirit of Christianity, the civil authorities were bound in duty to apply the punishment. While confiscation of property added insult to injury, the provision was designed to snuff out the family’s tendency to spread the heresy with a vengeance. Some allege that confiscations brought in revenue, but then, not all convicts were rich, and the proceeds were anyway meant for the upkeep of the court.

In those days scarcely any community or nation would tolerate the setting up of a creed different from the majoritarian creed. To put this historical fact in perspective, it is imperative to note what was done by those who left the Catholic Church, advocating private judgment and criticising the Inquisition: the pseudo-Reformers Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, and their adherents, in turn were prompt in using torture against those who differed from them in matters of belief. In the sixteenth century, thousands of non-Anglicans were killed in England at the behest of King Henry VIII; in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the American Puritans conducted inquisitions and burnings at the stake. The practice continued long after the pseudo-Reformation. The French Revolution, and the Mexican and Russian revolutions at the beginning of the twentieth century, had summary executions galore.

A redeeming feature of the Inquisition was that it closed the era of summary executions and considerably reduced death penalty sentences. As stated by Henry Charles Lea, in A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages, “however much we may deprecate the means used for its suppression [of heresy] and commiserate those who suffered for conscience’ sake, we cannot but admit that the cause of orthodoxy was in this case the cause of progress and civilization.” He stressed that “the Inquisition was not an organization arbitrarily devised and imposed upon the judicial system of Christendom by the ambition or fanaticism of the Church. It was rather a natural – one may almost say an inevitable – evolution of the forces at work in the thirteenth century, and no one can rightly appreciate the process of its development and the results of its activity without a somewhat minute consideration of the factors controlling the minds and souls of men during the ages which laid the foundation of modern civilization.”

Bernard Shaw put it down very categorically: “… Nobody thinks of these liquidations [of lower animals] as punishments, nor expiations, nor sacrifices, nor anything but what they really are: sheer necessities. Precisely the same necessity arises in the daily-occurring cases of incorrigibly mischievous human beings. They are vermin in the commonwealth, ferocious wild beasts on our highways, robbers and crooks of all sorts.”

What’s the scene in the early twenty-first century? Thirty per cent of the countries under the United Nations have retained capital punishment, and some have extended its scope. Iran, Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and the Philippines, to name a few, impose a death sentence for importation and/or possession of drugs. Several others do so for various economic crimes, including bribery and corruption of public officials, embezzlement of public funds, currency speculation, and the theft of large sums of money. Sexual offences are also punishable similarly in about two dozen countries, including most Islamic states. China holds executions regularly for a wide variety of reasons.

Is modern society, then, any more humane than medieval society? How many consciences are pricked by the same procedures prevailing in our day and age? The inquisitorial method is still used in criminal investigation in several countries, including India; confessions are extracted under preventive detention in every region of the world; freshly devised torture instruments are rampant; protracted and expensive legal procedures in secular courts are almost a denial of justice; and, finally, the moral responsibility to decide between life and death was as great for the inquisitor then as it is now for the modern judge in countries that uphold capital punishment.