Steer clear of toxic emotions

March 13, 2020Choices,Spiritual murder,Toxic emotions,Being for GodLent,Reflections

Lent 2020 – Day 15

Readings: Gen 37, 3-4, 12-13a. 17b-28; Ps 104, 16-21; Mt 21, 33-43, 45-46

Bitterness, envy, jealousy, anger and hatred are toxic: even more so when they envelop the family, where only charity should reign. Alas, the betrayal of Joseph by his siblings is rampant today, for petty honours or material gains.

Joseph prefigures Jesus, who was killed by the very people who He had come to save. Many were aware of His divinity, nonetheless conspired against Him; others stood by and watched, and a few piously shed tears. In the parable of the vineyard, Our Lord hints at the fate that awaits Him.

Today, there are coteries with no qualms about denying God and currying favour with the world. They share space with cliques that cause untold suffering to whoever observes the Lord’s commandments. When they make perverse suggestions or give immoral advice to the unsuspecting they are guilty of spiritual murder. All of which amounts to stabbing the Lord a thousand times every day.

Let’s get out of such circles and decidedly be with and for the Lord our God; it’s a choice we will never regret.

Trust in the Lord with all your heart

March 12, 2020Trust,Grateful heart,conversionLent,Reflections

Lent 2020 – Day 14

Readings: Jer 17, 5-10; Ps 1, 1-2, 3, 4, 6; Lk 16, 19-31

Jeremiah fearlessly denounced even kings and priests; seeing through the fallen nature of man, he declared that nothing short of a conversion could save him. “Blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord,” he said.

The Gospel draws our attention to a rich man who trusted in himself and in the good things of life; he failed to turn to the Lord with a grateful heart and to his own neighbour with concern. When he died, he was tormented in hell while the poor man was in God’s bosom.

Let’s be dutiful people, praying at all times. Let’s be kind and generous, trusting in the Lord our God: we owe Him every moment of our being. And let our conversion begin today; tomorrow may be too late.

It's not lonely at the top, we have the Lord by our side

March 11, 2020Humility,Jeremiah,Leadership,Service,ResponsibilityLent,Reflections

Lent 2020 – Day 13

Readings: Jer 18, 18-20; Ps 30, 5-6, 14, 15-16; Jn 6, 63; Mt 20, 17-28

'It’s lonely at the top' is perhaps what Jeremiah felt at first when spurned by his people. Our parents and our God feel the same when we recklessly reject their plans and even rebel if things don’t turn out to our liking. Although we're free to propose, we must let God dispose: this technique is not only a stress-buster but also a herald of great blessings.

When Calvary was just round the corner, Jesus kept spoke to his disciples about wielding responsibility with care and concern for the people. “Whoever would be great among you must be your servant… even as the Son of man came not to be served but to serve,” said He.

Don’t leaders get involved in petty squabbles and at times people envy their power? Whether leaders or followers, let’s realise that all have a cross to bear; life shouldn’t be only about self but also about helping the other.

God-given tasks do entail responsibility but when we trust in the Lord, saying “Your words, Lord, are spirit and life,” we find ourselves smiling and never feel lonely at the top.

We have to serve God and neighbour

March 10, 2020Vanity,Humility,Service,God the FatherLent,Reflections

Day 12

Readings: Is 1, 10, 16-20; Ps 48, 8-9, 16-17, 21.23; Mt 23, 1-12

Isaiah recommends that we make a clean breast of our wrongdoings and pray for God’s pardon. Further on the proactive side, we need to take in the Word of God in all humility and practise even simple acts of kindness.

Jesus has a special word for leaders of all times, of the kind that don’t practise what they preach.... They are like the Pharisees and Scribes of yore, self-serving and even exploitative; in their vanity hanker after titles and draw the people to themselves rather than joyfully showing them the way to the heavenly Father.

That’s the context in which Jesus said that God alone is our Master, Teacher or Father…. Yet again, Jesus uses hyperbolic language to drive home a point: that the leaders should be service-oriented, for “whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

Jesus humbled himself taking the form of a servant and we are called to do likewise: serve God by serving our neighbour.

Repentance is key

March 9, 2020Forgiveness,God is merciful,Trust in God,Repentance,God is LoveLent,Reflections

Day 11

Readings: Dan 9, 4b-10; Ps 78, 8-9, 11-13; Lk 6, 36-38

Daniel makes a fervent plea for repentance: ours is a God who is steadfast in love and keeps His covenant. We are in the depths of distress; it is only fair to request the Lord to not hold the guilt of our fathers against us. Indeed, if God were to be only just and not merciful, who would survive?

For our part, we must resolve to turn a new leaf and go ahead, like prodigal sons, saying, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you.’

Jesus, who has taught us to say, ‘Forgive us as we forgive those who trespass against us,’ also reminds us to be merciful and to not judge rashly; to condemn not, if we wish to not be condemned; to give generously, for the measure in which we give we shall receive.... But to get here, repentance is of the essence.

Taming our Tongues this Lent

March 8, 2020Tongue Fast,Fasting,Self-improvement,Lent,Spiritual ReadingSelf-Improvement

30 Days to Taming your Tongue, by Deborah Smith Pegues.

Authentic Books, Secunderabad.

Indian edition reprint, 2015.

ISBN 978-817362-731-6. 141 pp, Price not indicated.

A book I chanced upon months ago is going to be part of my spiritual reading this Lent. It dwells on a very important aspect of fasting, or what the author calls a “tongue fast”. Deborah Smith Pegues’30 Days to Taming your Tongue is thus most appropriate for the remaining thirty-odd days of Lent.

You are bound to be tongue-tied when you run through the contents page: thirty chapters featuring thirty types of tongue you wouldn’t think existed. Here they go:

- the lying tongue

- the flattering tongue

- the manipulating tongue

- the hasty tongue

- the divisive tongue

- the argumentative tongue

- the boasting tongue

- the self-deprecating tongue

- the slandering tongue

- the gossiping tongue

- the meddling tongue

- the betraying tongue

- the belittling tongue

- the cynical tongue

- the know-it-all tongue

- the harsh tongue

- the tactless tongue

- the intimidating tongue

- the rude tongue

- the judgmental tongue

- the self-absorbed tongue

- the cursing tongue

- the complaining tongue

- the retaliating tongue

- the accusing tongue

- the discouraging tongue

- the doubting tongue

- the loquacious tongue

- the indiscreet tongue

- the silent tongue

Did you ever imagine a tongue could be so versatile? The list reads like progeny of one and the same tongue: notice they have the same “surname”!

Besides the theme, another feature that makes this book suitable for the season is that it is Scripture-based. In the prologue, the author quotes James 3:8: “No man can tame the tongue.” She states our hope is in “the Spirit of God”, to whom we must entrust the unruly member to be subjected on a daily basis.

How do we begin the process? The first step is to admit that we could be guilty of many of the negative uses of the tongue listed above; the truth will make us free. A Biblical quote at the head of each chapter is very reassuring. Then there are short stories, anecdotes, soul-searching questions and Scripture-based personal testimonies that combine to make each chapter a tongue- and life-changing experience. A positive affirmation or resolution at the end of each chapter rounds it off beautifully.

I am hopeful that a thirty-day crash course, or fast course, if you like, will give us a wholesome tongue, such that we will speak what is pleasing to God. The author, who is an experienced certified public accountant, Bible teacher, speaker, certified behavioural consultant specialising in understanding personality temperaments, writer and housewife of over twenty-five years’ standing, assures us that we will not be turned into “a Passive Patsy or a Timid Tom who avoids expressing personal boundaries, desires, or displeasure with a situation.” She recognises that most interpersonal problems will not be resolved without being confronted; however, there is a time and a way to say everything.

It may well take one less than a month to reading this valuable book; but I would love to go slow, meditating on each chapter. In the epilogue, the author recommends homing in “on areas where your mouth is particularly challenged.” One may have to spend several days or weeks on a lying tongue, for instance, and on a cursing tongue none at all.

To assess our daily progress there is a “tongue evaluation checklist” in Appendix A. Considering it more effective to focus on implementing positive behaviour than trying to avoid the negative, Appendix B offers over thirty “alternative uses of the tongue” that will bring glory to God and improve our interactions and relationships. Appendix C has passages comprising an “arsenal of tongue scriptures” that will fortify us and revolutionise our conversation.

The author very wisely remarks, “Teachers often teach that which they need to learn themselves.” And I say with the author, “I am no different.” Like her who wrote the book primarily for herself, I write this not as a review but primarily as a notice concerning a book that could help us to transform our tongues into a “wellspring of life.”

Are we spiritually awake?

March 8, 2020Response to God's Call,TransfigurationLent,Reflections

Lent 2020 - Day 12

Readings: Gen 12, 1-4; Ps 32, 4-5, 18-19, 20-22; Mt 1-9

Had Abram not responded to Yahweh’s call, there would be no Jewish people. He responded to God’s instruction to leave the country: it was a saga of hardships, a saga that bore fruit.

St Paul similarly exhorts us to undertake life’s pilgrim journey, relying on the power of God and testifying to Him. We are privileged to have been called.

In the Gospel, Jesus receives an endorsement in those glorious words from God the Father, the real import of which becomes clear only after the Resurrection.

What is our response to God’s call? Our everyday situations are seed of great things to come. Once in a while we may be privileged to witness a ‘transfiguration’; even then we may show a lacklustre response. So absorbed are we in our chores that we fail to get the larger picture.

Everything will change for the better the moment we are convinced that Jesus is the Son of the true God. We can be considered spiritually awake if we can we sing, “Our soul is waiting for the Lord”.

God doesn't need us to be picture-perfect

March 7, 2020PerfectionLent,Reflections

Lent 2020 - Day 11

Readings: Deut 26, 16-19; Ps 118, 1-8; Mt 5, 43-48

“Be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect” is certainly a most curious and challenging mandate. What ‘perfection’ does Our Lord require of us, and why, when we are naturally flawed and will perhaps remain so?

But then, weren’t man and woman originally ‘perfect’, made in God’s image and likeness… until Original Sin spoiled the show?! Down the line, Moses urged the Jews to keep the law and justify the title of ‘Chosen Race’.

Whereas that relationship sounds ceremonial and self-seeking, Jesus, the new and greater Moses, not only proposes a filial relationship with God, He requires that this be reflected in our association with our fellow beings too. Thus, He perfects the old law, mandating that we love and pray even for those who regard themselves as our enemies….

Not to worry – God doesn’t demand that we be picture-perfect! He looks straight at our hearts moving continually to overcome our natural flaws, desirous of restoring things to their pristine state – in His image and likeness! Perfection is not that curious after all if we live each moment in God’s grace. And the search for perfection is less of a challenge when we are still and know that He is God – for in truth it is God who wins all our battles for us.

Called to be authentic

March 6, 2020Authenticity,RighteousnessLent,Reflections

The readings of the day invite us to reflect on how authentic our righteousness really is. Are we busy helping everybody else while neglecting our very own people struggling at home? Do we find ourselves strutting at a church service when we still have scores to settle with family or neighbours?

God wants us to do a self-appraisal: without this there can be no change for the better. He happily welcomes even the greatest sinner who has had a change of heart. “None of the transgressions which he has committed shall be remembered against him.” But if a good man turns wicked, “none of the righteous deeds which he has done shall be remembered” for much is expected from those to whom much has been given.

That is not asking for too much. Once on the path of righteousness we will experience true freedom. What’s more, we will have entry into the kingdom of Heaven which is the crown of righteousness.

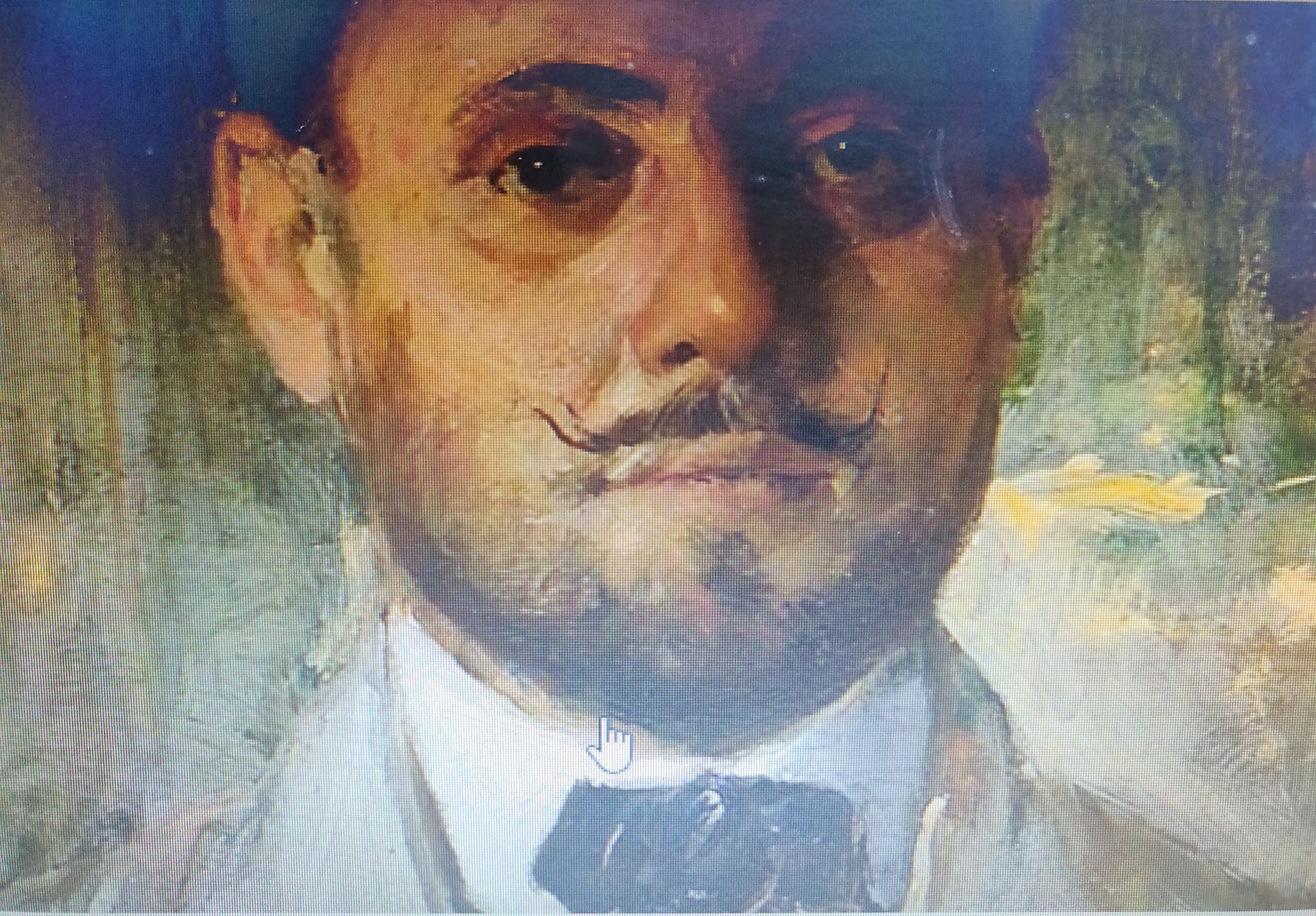

All about Amor

March 5, 2020Macau,Earliest films in Goa,Goa,António Xavier Trindade,Manuel Antunes Amor,Joaquim de Araújo Mascarenhas,Fundação Oriente,Resposta a uma provocação,Dr Marcella Sirhandi,Boletim de Educação e EnsinoPersonality

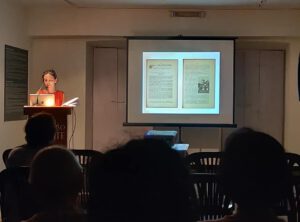

Maria do Carmo Piçarra’s talk at Fundação Oriente, Panjim, was titled “Behind the Portrait of Antunes Amor, Educator and Pioneer of Cinema in Goa”. A researcher at Instituto de Comunicação da Nova (ICNOVA), Lisbon; assistant professor at University of the Arts, London (UAL); and a Fundação Oriente scholar, Piçarra holds a doctorate in Communication Sciences. She is a film programmer; author of several publications, among them Azuis Ultramarinos. Propaganda colonial e censura no cinema do Estado Novo (2015) and Salazar vai ao cinema (2006, 2011), and principal editor of (Re)Imagining African Independence. Film, Visual Arts and the Fall of the Portuguese Empire (2017).

Piçarra contextualised a painting titled “Mr. Amor. The Portuguese Agent” (1917) from the Trindade Collection on permanent display. That striking piece of art by the Bombay-based Goan painter António Xavier Trindade (1870-1935) was gifted to the Foundation by Dr Marcella Sirhandi, a friend and biographer of the artist.

Piçarra spoke of Amor’s cinematographic forays in Macau, where he screened his first amateur movie. She also mentioned the films he made about school life, history, and so on, while in Goa. A strong defender of the pedagogical and propagandist uses of cinema, Amor had several of his films shown in local halls.

The precious little I already knew of Manuel Antunes Amor (1881-1940) I had heard from my father a quarter of a century ago; I was now surprised to see him again! Trained in Germany in the early twentieth century, Amor (‘Love’, in Portuguese) was a self-opinionated gentleman whose tenures as primary school inspector in Goa (1916, 1922) were mired in controversy.

Finally, Piçarra's remark that Amor was particularly suspicious of lawyers reminded me of that high-profile polemic he had with Joaquim de Araújo Mascarenhas (1886-1946), a Goan legal eagle who doubled as Portuguese language teacher at Liceu Nacional de Nova Goa. A lethal combination it proved to be.

An article titled “O ensino primário e a incúria do Estado” ('Primary school education and State neglect') that Araújo Mascarenhas wrote for the maiden issue of the monthly Boletim de Educação e Ensino (April 1927) made Amor see red. He wrote a censorious rejoinder, “Sem autoridade nem razão” ('Devoid of authority or reason'), in the very next edition.

Araújo Mascarenhas dashed off a point-by-point rebuttal. The Boletim’s editorial board that comprised primary school teachers declined to publish it, possibly fearing the inspector's wrath. It led the redoubtable polemist to bring out a volume titled Resposta a uma provocação ('In Response to a Provocation').

Sadly, the Boletim folded up in August that year, but not before the long series of events had vitiated the atmosphere. No wonder the very gifted Mr Amor was someone many Goans loved to hate.