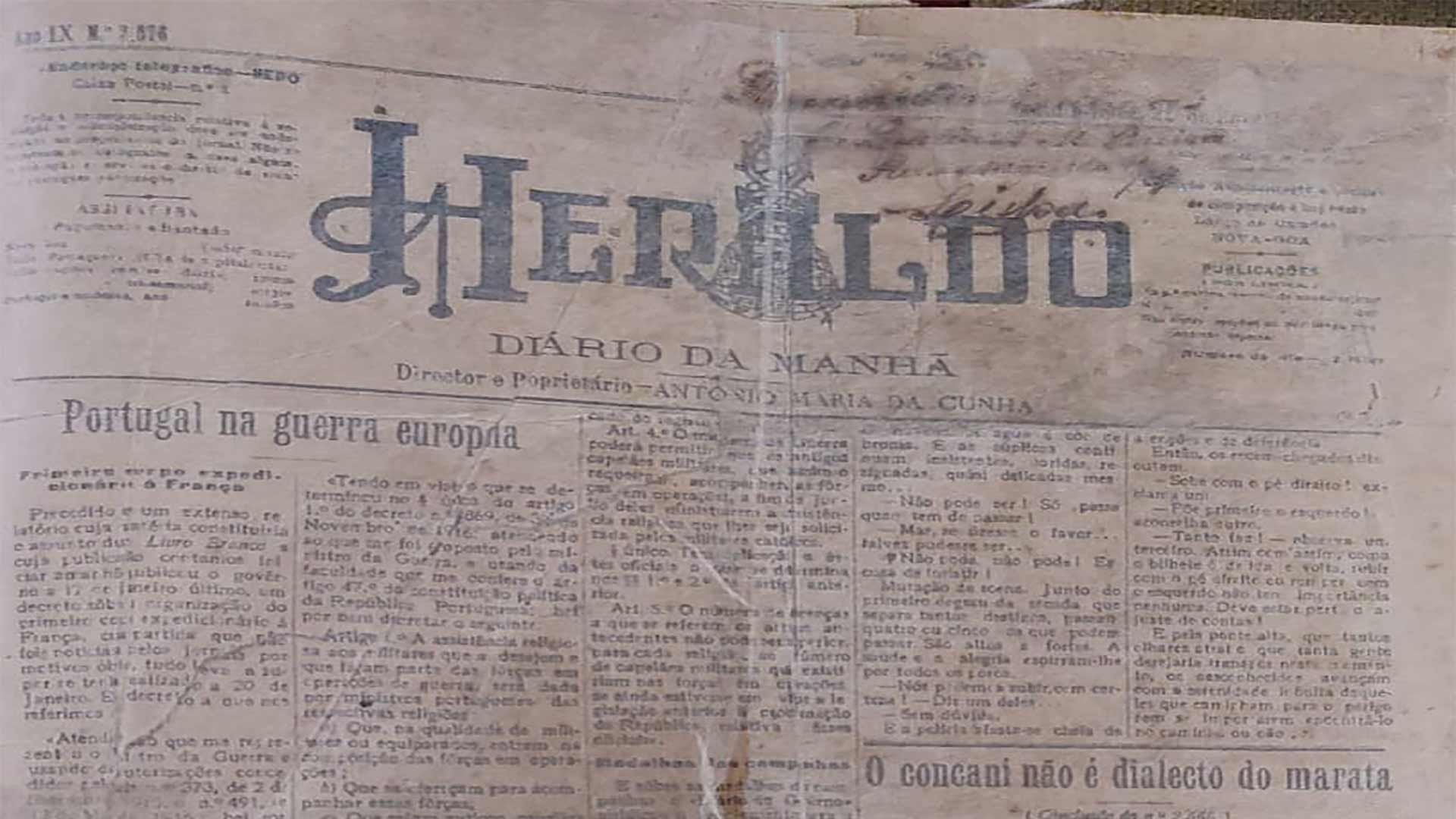

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi – 9

Part 9 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata"

by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

(In Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2576, 22 February 1917, pp. 1-2)

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

An important question now arises, which can also be regarded as a sensible and weighty objection. It being impossible, as a result of those significant discrepancies, that Konkani, as we know it, be a dialect of Marathi, how does one explain so many analogies, especially morphological, between the two languages?

It is a complex issue. It demands a lot of learning and long elucidation. In addition to philology, it needs history and ethnology to step in. I turned it over many times in my mind, but did not obtain satisfactory and definitive results, for want of some indispensable elements.

Hence, I am not on firm ground. I may put across my point of view if I get some respite from my occupations, and I find sufficient motivation, for elderly people generally flounder.

Meanwhile, responding to frantic demands, I will declare that I would not be averse to the hypothesis that Marathi is the subsoil (not mother, please note) of Konkani or the superinduction or superfetation. Which of the hypotheses is more plausible, if there is need of any?

This time my only goal was to break a lance for ‘my lady’ and to avenge the wild invectives that cowardly hands threw at her, mercilessly and with iron fists, but also – sorry to say! – with neither knowledge nor conscience. I end crudely, with not much of a method and hurriedly, so as not to delay the typographic proofs of more useful and less sentimental and abstract work. Maybe some minor slips escaped my notice – a fact that is understandable for him who works from his bed and on subjects that require frequent consultation of books.

I do not mean to say, however, that nothing has been written about Konkani that is sensible and deserving of praise, nor that I am displeased by opinions differing from mine. On the contrary, I disapprove of ipse dixit, and I believe that intellectual slavery is the worst kind of slavery. It is not something in which we say Roma locuta est, lis finita est.

But there are opinions. Opinions expressed without full grasp of the subject, albeit with literary trappings, only with the itch to show off and to give tit for tat, have no greater value than those coming from inmates of a mental asylum. They are combated, not with a view to convincing the opinion holders, but to prevent those opinions from getting established.

It goes without saying that, whoever lacks even elementary notions of general philology, and is unaware of the origin, history, phrases, dialects, literature, nature of vocabulary, grammar of a language, and her relations with her sisters and neighbours, cannot expatiate on their merits or demerits, their progress or degeneration, their purity or corruption. Ne sutor ultra crepidam.

Speaking a language by listening does not qualify one to deal with its philology, which is a completely different thing. Adolfo Coelho and José Maria Rodrigues know more about Latin philology than Cicero and Horace did; and Max Muller and Brugmann know comparative Sanskrit philology better than did Panini, the prince of the world's grammarians.

But this is not how they think in Goa, for lack of common sense and intellectual discipline. Freedom of thought and of speech is no excuse for nonsense bordering on insanity. The Hindu who, on the occasion of the proclamation of the Republic, entered a church over there, holding a cigar in his mouth, proved, if anything, that he was utterly uncouth.

How many of those who have written about Konkani would know the right declination of a noun or conjugation of a verb, or how to analyse a passage by breaking down the words, distinguishing themes and inflections and indicating the etymology? Just how many people mistake the past tense of transitive verbs for active voice, and the sentence – hânvem ambó kheló – for ‘I ate a mango’, when, in reality, it means ‘the mango was eaten by me’!

It seems as though general belief over there has a say in everything that concerns our communities: Zâmkún zhânkún gâmvkar zâtá; one becomes a ganvkar through sheer chattering.

That results in a lot of vines and few grapes. If competent people took care to teach; if the ignorant cared about learning; if they talked less and worked more, it would be a win-win. We are so done with chatterboxes.

Fortunately, in the midst of disconcerting mists, a gleam of light is not lacking. I was deeply moved to learn that my venerable friend and most exemplary priest, Father Casimiro Cristóvão de Nazareth, had offered the local government a Portuguese-Konkani vocabulary, put together by him in collaboration with some knowledgeable people, to be published and distributed to schools.

I have no doubt that the work is of great merit. Father Nazareth, who trained from early years at the school of Filipe Néri Xavier and Miguel Vicente de Abreu, and who has been a busy bee throughout his life – tanquam apis argumentosa – and is a walking library of useful information, does not produce fake stuff nor is he a publicity seeker.

But to think that an eighty-five-year-old man, and moreover, blind like Tobias – quia aceptus eras Deo – is still working and making it a point to be of service to the country, while so many young people exhaust themselves with an hour’s reading and need to amuse themselves with manille and suposta and give in to banal and sinful talk: what a striking contrast and what an edifying lesson!

It pains my heart to remember – and this happens so often! – that the Portuguese government declined to publish his Mitras Lusitanas, a product of much labour and an ample mine of such precious information, collected with great tenacity from all the accessible sources. It occurs to me now that Counsellor Jaime Moniz told me that he would bother him with requests for books to read or to send to Rachol Seminary.

In any other civilized country, that monumental work would have been welcomed as a national glory, and an award given to its author, who neither made a profession out of his calling nor aspired to lucrative and showy positions. Of him, certainly, one cannot say that he was ‘toddy coconut tree’ – suretsó madd.

Certain happenings in Portugal lead people to believe that they live in some Zululand. From Rome, they recently sent me Pietro della Valle’s book, which cost twenty francs. The Customs office of Lisbon valued it at twenty escudos – over four times – and charged 1700 réis as duties! The bookseller's receipt was presented and it was proposed that they keep the book for fifteen escudos, thus making a profit of five. They threatened that they would value higher. And all that just because of the shoddy, dirty parchment binding, for which I didn't pay a penny!

Patriotism is a good and praiseworthy thing. Jesus Christ shed tears foreseeing the future ruin of his homeland. But I reject patriotism that forces me to distort the truth and trample on justice.

In conclusion, I must declare, in order to appease my conscience, that those vague references are not tantamount to personal contempt for those targeted, whom I know not and wish all the best, as well as all humanity. I would have liked to be entirely doctrinaire, if the subject so allowed it. I earnestly request the reader not to be curious to investigate who is hinted at in the above allusion. It is about doctrine, not people. Veritas et caritas super omnia.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 31, Nov-Dec 2024, pp 45-48

Trouble, Trust and Thanks

November 10, 2024Mass Readings

The Readings of today help us develop faith and trust, love and gratitude. As we inch closer to Advent, let us cleanse our hearts and minds that we may worthily receive the Divine Babe.

In the First Reading (1 Kings 17: 10-16), we learn about a famine that devastated Israel under king Ahab. Under these trying circumstances, a poor widow and her son received the prophet Elijah into their lowly home in Zarephath, a town on the Mediterranean coast. Their supply of flour and oil was at its fag end, yet miraculously it was not depleted until the famine itself came to an end. Truly, the needy are sometimes the more generous and welcoming.

Israel’s dry spell was a punishment for idolatry prevalent in the kingdom, but soon God turned things around. When the prophets of Baal prayed for rain, there was scorching sun; but after Elijah had restored Yahweh’s altar and offered sacrifice and prayers, it began to pour. This signalled the power of the true God and the end of the famine.

The miraculous episode is reminiscent of the wonders that St Joseph Vaz worked in Sri Lanka. After efforts by the kingdom’s false prophets had come to nought, the Goan apostle prayed for rain at an altar erected in a public square. Rain bucketed down, leaving only the area around the priest and the altar dry! The miracle was a defining moment for the Vazian apostolate: many embraced Catholicism and those that had fallen by the wayside returned to the faith.

In our own times, look at how the world went berserk in the days of Covid-19 even while self-proclaimed saviours became the new idols. What state of mind will we find ourselves in when the real D-day comes? Will we be prepared to welcome our Saviour? Therefore, come what may, we must swear our allegiance to Him right away, so that at the eleventh hour there is no vacillation nor succumbing to mental or physical vaccination.

It is such false prophets that Jesus in the Gospel (Mk 12: 38-44) railed against: ‘Beware of the scribes, who like to go about in long robes, and to have salutations in the market places and the best seats in the synagogues and the places of honour at feasts.’ They devour widows’ houses and for a pretence make long prayers. We could well add that then, instead of being run into jail, they are run into Parliament!

Such are the ways of the world, which the kingdom of Heaven will greatly condemn. The high-handed will be shown the door and the poor shall inherit the kingdom; those who mourn now shall be comforted, and those who weep, laugh. The same with the prophets... What prophet worth the salt has not been reviled, hated and excluded from his own land, by his own people, precisely for standing up and speaking up for God? He will be awarded the crown of righteousness.

Meanwhile, in the Gospel text too, there appears a poor widow. Like her Old Testament counterpart, who through her destitution trusted in the Lord, she too in her deprivation gave Him everything she had. And Jesus, seated opposite the treasury and watching people putting in their gifts, quickly made a distinction between those who had comfortably contributed out of their abundance and the poor widow who even out of her poverty put in two copper coins, her whole living!

It is not that Jesus summarily condemns the rich and commends the poor. In fact, it is not persons but faulty attitudes and acts that he censures. Those with wealth and/or intellect, how well do they serve God? Historically, we have umpteen examples of individuals, families, even countries, that have prioritised and served God in all things.

On the other hand, there are those who receive but never repay. ‘Kam zalem, voiz melo’ is a saying that comes promptly to mind: God is taken for granted. We get so puffed with pride that we think we can have it our way. No wonder, Jesus noted that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven.

The way out, then, is to be always in awe of God and to have a heart filled with love and gratitude, so we can sing with the Psalmist: ‘My soul, give praise to the Lord.’

Finally, the Second Reading (Heb. 9: 24-28) presents us the Christ who ‘has appeared once for all at the end of the age to put away sin by the sacrifice of Himself.’ A solemn and beautiful promise wraps it up, saying that ‘Christ, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for Him.’

Let us therefore do everything to be counted among those who await His Second Coming. Nothing compares to Him and to the time when the Son of Man will come, at an hour we do not expect. We have to be in a state of readiness, irrespective of our troubles. We have to trust in Him and be thankful at all times.

Banner: https://shorturl.at/pnCDx

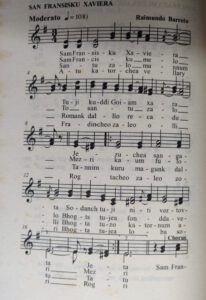

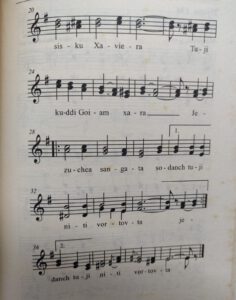

Hino em concani, de Raimundo Barreto, traduzido

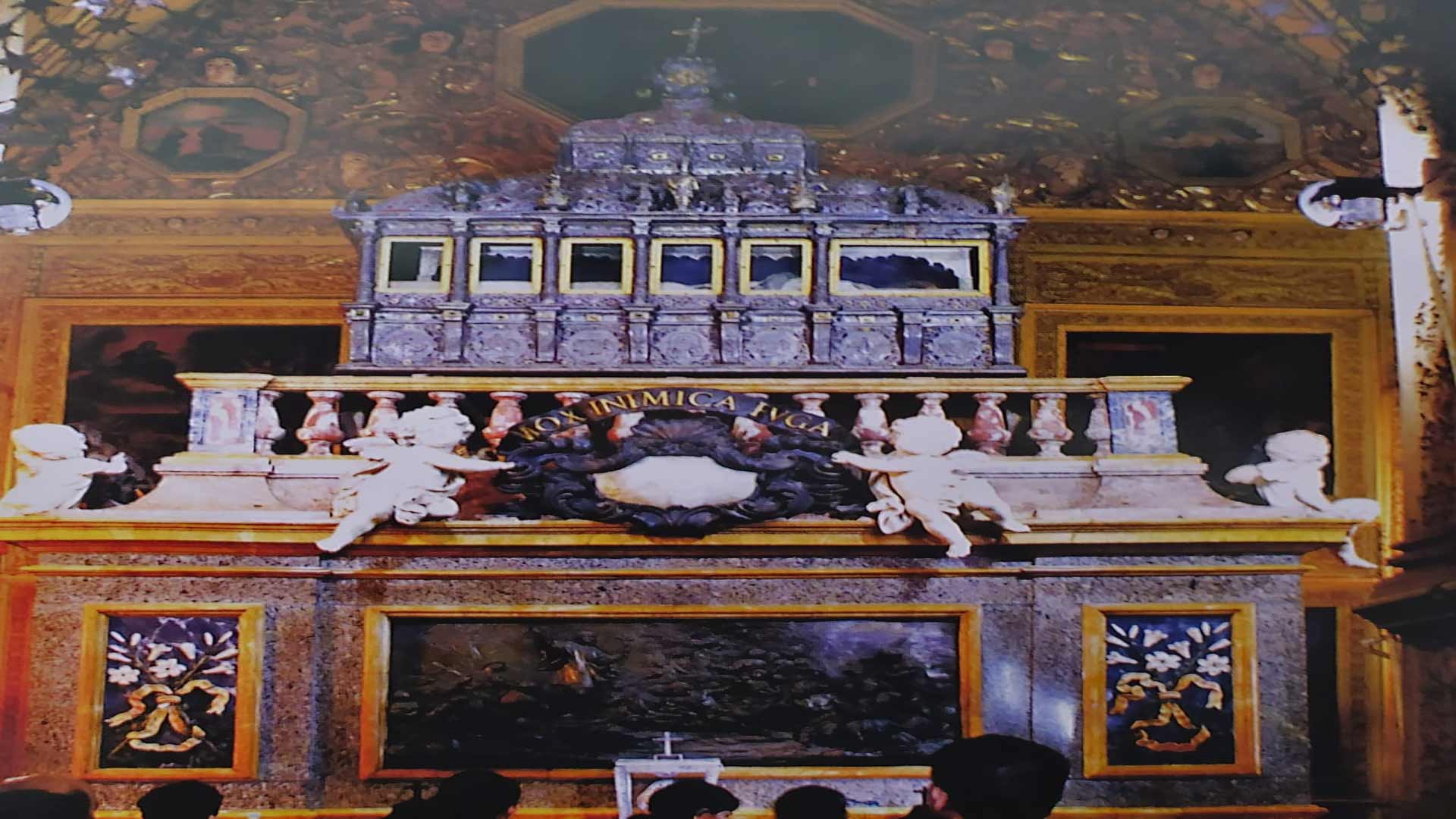

‘SAM FRANCISCU XAVIERA’: Goenchem Poramporik Gaion

‘SÃO FRANCISCO XAVIER’: Um Hino Tradicional de Goa

Utram ani Nad | Letra e Música de Raimundo Barreto

Portugez bhaxantor korpi | Tradução de Óscar de Noronha

Raimundo Barreto (1837-1906), oriundo de Loutulim e residente na Ilha da Divar, foi mestre-capela da Sé Catedral, na Velha Cidade de Goa. Compôs o hino a S. Francisco Xavier em acção de graças pela sua fuga milagrosa de um naufrágio no Mandovi.

1. Sam Franciscu Xaviera,

Tuji kuddi Goiam xara,

Jezuchea sangata

Sodanch tuji niti vortovta.

2. Sam Franciscu melo,

To santu zalo,

Mezrikaum fulolo,

Bhogta tujea fonddaveri.

3. Santu zalo mhonnun

Romank dal’llo recadu

Tannim kuru magunk dal’lli

Bhogta tuzo katornum atu.

4. Atu katorchea vellari

Fradincheo zaleo olli,

Rogtacheo zaleo zori,

Bhogta tujea loba sori.

5. Atu Romank vortanam

Doriach’m pannim zalem foro,

Crucifixu buddounum

Pannim tannem kelem nitollo.

6. Mezari tinteir peno,

Atantum ghetlea foli,

“Tum foro sant zaleari

Nixanni assinad kori!”

7. Foli mezari,

Atantum tinteir peno,

Tannem nanvom aplem kelem

Sam Francisc Xavier munnum.

8. Sindrecho kelo lobu,

Sodanch solicitadoru,

Tannem magunum ghetlo

Mosteir Saiba Bom Jezucho.

9. Sam Franciscach’ barreti,

Motiancheo correti,

Tumim arxe laun polleati,

Bhogta tuje sacerdoti.

10. Sam Franciscu Xaviera,

Sam Francisc Castelacha,

Tuji kuddi Goiam xara,

Atmo voikuntta nogra.

11. Bom Jezuchea altrari,

Tuji kuddi sepulcrari,

Tum Goiam xarach’ raza,

Sam Francisc Xavier amchea.

1. São Francisco Xavier,

Vós a Goa viestes jazer;

Em convívio com o Senhor

Exalareis sempr’ um santo odor.

2. São Francisco expirou

E a santidad’ ele conquistou;

Mangerico ali medrou

E a sua campa adornou.

3. O seu halo além brilhou,

À Cidade Eterna chegou;

Um sinal se lhes enviou,

O nobr’ antebraço se lhes doou.

4. No momento d’o braço cortar,

De mil frades houve lá um mar,

E o sangue a derramar,

A sua sotaina foi banhar.

5. Esse braço a Roma chegou,

Tod’ o mar alto se espumou;

O crucifixo mergulhou,

Tod’ a água logo se acalmou.

6. Pena e tint’ aí estão,

Uma folha na sua mão:

“Se de facto vós sois São,

Logo se verá p’la subscrição”.

7. Com os frades a sondar

E sem saber que del’ esperar,

Assinara por mister

O seu grande nome Xavier.

8. De modesto paramentar,

Andou sempre a solicitar

Um mosteiro com resplendor,

Esse Bom Jesus, Nosso Senhor.

9. O barrete de missionar,

E as pérolas do seu rezar;

Queiram os frades admirar

E a sua fé alimentar.

10. São Francisco, de Xavier

E de Jasso, nobre a valer;

À nossa Goa viestes jazer,

Vossa alma há-de resplandecer.

11. Lá do alto do Bom Jesus,

Lá do túm’lo de jaspe sem par;

Sois Senhor de Goa, da luz:

Eis o nosso Santo Xavier.

Mull | Fonte: Konkani Bhagtigitam, José Pereira, Ektavpi (Panaji: Goa Konkani Akademi, 2004). Xudhlekhan bhaxantor korpeachem. | Konkani Bhagtigitam, compilado por José Pereira (Panaji: Goa Konkani Akademi, 2004). A grafia foi actualizada pelo autor da tradução.

Utram ani Nad | Letra e pauta

Mull | Fonte: Songs of Praise / Adlim Kristi Bhogtigitam, de António da Costa (Goa: Goa 1556, Golden Heart Emporium, GoaBook.Club: 2016)

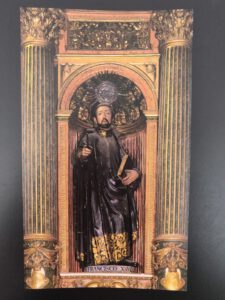

Imagens: Saint Francis Xavier: A Man for Others, de Miguel Corrêa Monteiro (Portugal: CTT Correios, 2006)

Love, for God’s sake!

Today’s Readings refer to love, about which we all wax philosophical. And we have the added advantage of getting Our Lord’s invaluable perspective on it. After all, in Him we have a High Priest who offered the supreme sacrifice of His life for the love of mankind.

From the First Reading (Deut. 6: 2-6) we can conclude that God – the True God, and He alone – is the first and last object of our love; everything else flows from there on. Hence, Moses said to the people, ‘Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord; and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might.’ Totally.

Considering the extent of God’s love for us, is it not our bounden duty to love Him in return? His love is inscribed upon our hearts, for we are made in the image and likeness of God Who is Love. In this regard, we may recall the basic teaching we imbibed in our catechism class, in the form of two simple yet profound questions and answers: ‘Who made you?’ God made me. ‘Why did God make you?’ God made me to know Him, love Him and serve Him in this world and to be happy with Him forever in the next.

Centuries after Moses, Jesus added a new dimension to love when a scribe asked Him to identify the greatest commandment. In today’s Gospel (Mk 12: 28-34), our Divine Master quotes verbatim that passage from Deuteronomy, and adds: ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself. There is no other commandment greater than these.’ The scribe was quick to admit, to Jesus’ delight, that ‘to love one’s neighbour as oneself is much more than all whole burnt offerings and sacrifices.’

This brings us face to face with three loves, so to speak: love of God, love of neighbour and love of self. And the question is, how do we begin loving? Love of self, which comes naturally to us, can quickly turn into narcissism and pride. For that matter, love of neighbour is more easily said than done, for we are quicker to love ourselves than to love our neighbours, aren’t we?

That is because self-interest is a survival skill that rules the roost. So, it seems easier to relate to God – by loving Him who first loved us. But then, some may wonder how we can love God who is invisible when we haven’t first loved our neighbour who is next door... The fact is that, left to ourselves, our fallen nature determines what we do. Thus, loving becomes an uphill task unless we receive God’s grace – of which the Sacraments are mystical channels.

As for the love of God, it is no plain emotion or whim. It is a resolution that made upon due appreciation of God’s plan of salvation… When we see that He who is wrapped in purple robes, with planets in His care, has pity on the least of things (as Yeats puts it in the ‘Ballad of Father Gilligan’); that He who looks on the birds of the sky surely cares for us too, who are more valuable in His eyes (Cf. Mt 6: 26) – we open ourselves to God. Finally, the realisation that the world is transitory where Heaven is where we spend eternity clinches it.

By such a supernatural approach to life, power and pelf lose their hold on us. When we compare our present life with what God has promised, people and things, and even self, pale into insignificance. Then we are convinced that ‘He must increase, but I must decrease,’ as St John the Baptist has stressed. By and by, at a higher rung of our ascent to God, we begin to say with St Paul: ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me’ (Gal 2: 20). Then, God’s love in us overflows into our neighbour’s heart through what we do.

It would be silly to believe that loving God, loving neighbour and loving self happens sequentially. It is one whole. But does it mean that one must indiscriminately bow to each and every one? Consider the person who gives scandal and becomes his neighbour’s tempter; he damages virtue and integrity and may even draw his brother into spiritual death (Cf. CCC #2284). Can we relate to them in the same way as we do to those who follow God’s commandments and stand by Him?

Much harm is caused to the world when, in the name of ‘love’, we close our eyes to malicious and criminal acts, saying, ‘Who am I to judge?’ There are those who preach love as long as they have not been offended – and yet it matters little to them if God is offended! But then, can we wash our hands like Pilate? Must we not stand up, speak up?

God calls on us to distinguish between what is true and false, good and bad, right and wrong. That is, we need to discern – and not have acts of foolishness styled as acts of love. For instance, opening your houses and parishes and countries to people inimical to what we believe as Christians is a recipe for self-destruction. Our Lord’s command to ‘be cunning as a serpent and yet as harmless as doves’ (Mt 10: 16) is thus pertinent even when we talk of love.

We may therefore conclude that we must love God above all things – for His own sake; and we must love our neighbour as ourselves – for the love of God! (Cf. CCC # 1822).

Banner: https://shorturl.at/1iVrn

The Core of Jericho

A single theme runs through the First and the Third Reading: disability, which is important to look at in both literal and figurative senses. We must indeed look further than what is obvious when the Scriptures speak of physical or material loss. We must seek the treasure that lies hidden beneath the surface, and it’s always something transformative!

In the First Reading (Jer 31: 7-9), Jeremiah calls upon the Israelites to sing the praises of patriarch Jacob.[1] While they were reeling under the Assyrian yoke, the prophet urges them to not lose hope. God had promised to free them and bring them back from far and wide. In fact, the mention here of the blind and the lame and the woman in travail speaks volumes of God’s loving kindness.

God singles out Ephraim, which had settled in Samaria (central Israel), as it was the foremost of the ten tribes. Their cry would be their prayer, which God would hear. He would lead His people to lush pastures and restful waters. However, this is not about physical health alone; it is about restoring the Chosen People to spiritual health. It is not so much about their political liberation as it is about their much-needed liberation from the bondage of sin.

A grateful lot would readily chant Psalm 125: 1-6, which puts it all so beautifully: ‘What marvels the Lord worked for us! Indeed, we were glad!... They go out, they go out, full of tears, carrying seed for the sowing, they come back, they come back, full of song, carrying their sheaves.’ Thus, God’s promise wasn’t a dream but a reality.

Even greater marvels awaited the people of Israel down the centuries. In the Gospel (Mk 10: 46-52), we see Jesus leaving the town of Jericho with His disciples and a great multitude, when Bartimaeus, a blind beggar, on hearing that Jesus was passing by, persistently cried out: ‘Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!’ On hearing that appeal, the Master sought to heal the blind man, much to the disciples’ surprise, for they had tried to box him out.

Why did Jesus, who was all-knowing, say to the blindman, ‘What do you want of me?’ Possibly, to get him to articulate a more specific prayer and thus be more intimately involved in his own healing. The sightless man’s plea – ‘Master, let me receive my sight’ – was as straightforward as his cure was instantaneous. His words indicate that he was not born blind but had lost his sight. ‘Immediately he received his sight and followed Him on the way.’

Bartimaeus’ deep and unwavering faith made him well, said Jesus. The other lesson for us to imbibe is that the beneficiary’s heart filled with gratitude impelled him to follow Jesus.[2] So, it is not about physical disability alone; it is about overcoming our spiritual disability – call it what you will: blindness, deafness, numbness, or whatever – and having a change of heart. Elsewhere, Jesus railed: ‘You hypocrites! You know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky… why do you not judge for yourselves what is right?’ (Lk 12: 56) Jesus was only alerting His people to the need for faith.

It is often our indifference, not to say malice, that comes in the way of our spiritual progress. Yet, there is nothing to worry, for our High Priest in Heaven knows the inner recesses of our soul and can provide the right balm. That is how He partakes of the human condition. Similarly, as the Second Reading (Heb 5: 1-6) points out, ‘every high priest chosen from among men is appointed to act on behalf of men in relation to God, to offer gifts and sacrifices for sins.’ Being sinful and weak, we must atone for our sins and deal gently with our fellow beings, who are also beset with weakness.

Finally, the Readings don’t merely indicate a purpose but point to a process as well. What we see in the Old Testament actually happens in the New. Hence, a word about core of Jericho. It was the first city – and a well-fortified one at that – which the Israelites conquered after occupying the Promised Land. By strictly following God’s (apparently foolhardy) instructions, they were able to bring down the walls of Jericho.[3] They did so by virtue of their faith – the same that helped the blind beggar shed his blindness as Jesus was leaving Jericho. And it is the same faith that knocks down the Jericho wall of our hearts, letting God touch the core of our being.

[1] He was a son Isaac and Rebecca and grandson to Abraham. When there was a drought in his homeland Canaan, Jacob moved to Egypt, where his son Joseph wielded influence in the Pharaoh’s court. Jacob came to be regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites.

[2] Both St Mark and St Luke talk of one blindman (the latter does not register his name), whereas St Matthew mentions two, just as he does in the case of the possessed men (Cf. Mt 20: 29-34).

[3] See Joshua 6: 1-27

Mario is Forever

October 23, 2024Gerson da Cunha,The World of Mario... Seriously Funny!,Momentos do meu Passado,Mario documentary,Dolcy D'Cruz,Mario de Miranda,Savio de Noronha,Shyam Benegal,Doordarshan Goa,Gerard da Cunha,The World of Mario,Fernando de Noronha,Herald Cafe,Mario,Uday KamatPersonality

When contacted by Dolcy D'Cruz of Goa's leading English-language daily Herald, for comments on the public screening of the documentary "The World of Mario... Seriously Funny!", https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Fj-KEN2kQI , researched and scripted by me for Doordarshan Goa, here is what I said, in reply to the journalist's questions:

On challenges faced

Mario had the world for his canvas, so the main challenge was to be able to truly cover his creative life in a short documentary.

Identifying the right talking heads and liaising with them was another challenge. His sister Fatima gave us valuable inputs. And we also got on board film-maker Shyam Benegal, Indian adman Gerson da Cunha, architect Gerard da Cunha who owns the Mario Gallery, and many others.

https://epaper.heraldgoa.in/oHeraldo?eid=1&edate=22/10/2024&pgid=52727&device=desktop&view=2

On his relevance

Mario is a curious case of a self-trained artist who had different styles, worked with different mediums, and across the print and electronic media.

It is a civic duty to pay homage to the greats of our land. Mario loved Goa and worked towards preserving our culture and heritage. Many tourists used to come here in the hope of finding ‘Mario’s Goa’ but often they were disappointed on seeing that Goa had changed a lot.

On a personal note

Working on Mario took me back to my Bal Bharati textbook. As kids, few must have known that the illustrations were done by a great Goan artist.  Then, I saw him and his dog in the pages of the Illustrated Weekly. Finally, I met Mario face to face for the first time in 1987, at the Gulbenkian in Lisbon. On his exhibition catalogue he scribbled, ‘For Oscar, Saudades, Mario’, and suddenly I felt I’d known him forever.

Then, I saw him and his dog in the pages of the Illustrated Weekly. Finally, I met Mario face to face for the first time in 1987, at the Gulbenkian in Lisbon. On his exhibition catalogue he scribbled, ‘For Oscar, Saudades, Mario’, and suddenly I felt I’d known him forever.

Also, he very kindly illustrated my dad Fernando de Noronha’s memoirs, Momentos do meu Passado, which he said had brought back nostalgic memories of his youth in Goa.

To me, those saudades remain – of a gentleman with a twinkle in his eye, an unassuming genius, a lovable character, just like all those that he has immortalized in his illustrations and cartoons.

-o-o-o-o-

Here are a few pictures of the event, which comprised the first public screening of the "Stories and Documentaries" series at DD Goa auditorium, inauguration of the digital screen and felicitation of the documentary team, and superannuation farewell of a DD Goa veteran:

Governor of Goa addressing the audience

Governor of Goa addressing the audience

Pics, courtesy: Bambino Dias, Thomas Rodrigues Lorraine de Noronha, Miguel Furtado and Emmanuel de Noronha

Passion and Glory

‘The greatness and the power and the glory and the majesty and the splendour’ that the Book of Chronicles (29: 11) speaks of as belonging to the Lord belong to us humans as well. The difference is that in God’s hands those values are transformative; in human hands, they turn ordinary and dull, and often degenerative.

Today’s Readings speak of the purpose of those values and how to avoid the most obvious pitfalls. The First Reading (Is 53: 10-11) is taken from the Fourth Song of the Servant, which begins thus: ‘Behold, my servant shall prosper; he shall be exalted and lifted up, and shall be very high.’ While this is sure to give every human a high, in the verses that follow, which make up today’s Reading, we see that glory comes with a price – also very high.

Isaiah’s Suffering Servant prefigured Jesus Christ. His Song indicated that He would be despised, rejected, esteemed not, afflicted, wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities, oppressed, stricken… And if this is not a description of Our Lord’s Passion, what is? He redeemed us through His Passion and Death. The Jews, too, traditionally believed that the Suffering Servant referred to the Messiah or Redeemer who was to come to Zion. But, irony of ironies, they rejected Him when He actually came!

Hence, in the Gospel (Mk 10: 35-45), Our Lord makes it amply clear that the Son of Man came to give His life as a ransom. He did not come to enjoy earthly glory but rather to suffer for the sins of humankind and raise it to a glory that is eternal. Here, two of His close disciples – James and John, sons of Zebedee – were hideously off the mark. They sought the highest ministerial berths from Him who they thought had come to rule over Israel! Our Lord obliged the Good Thief instead, who was crucified to His right hand….

However, handling the disciples’ feelings of self-importance with utmost care, Jesus didn’t say an outright no, but asked them what they wanted Him to do for them. And then came the full truth: ‘You do not know what you are asking.’ Which is often the case with you and me; we want gains without the pains. Yet, it was not for Jesus to grant their request, but for God the Father to decide. The high place they coveted would be ‘for those for whom it has been prepared.’

This is so much the story of our own lives. As the saying goes, man proposes; God disposes. Although there is nothing wrong in proposing, this must be accompanied by a wilful surrender to the divine will. God’s will can be way different from our own, so we must be ready to accept it, firmly trusting that it will work for our good. The golden rule, then, is to believe that ‘there is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens’ (Eccl 3: 1).

Setting the common good above everything could be another guiding principle. Also, we must ascertain that our goal has a higher purpose. This sanctifies what we desire – power and glory included. If it be for God, let it be done! That is what a 300,000-plus gathering meant to say when they sang ‘We want God’, on John Paul II’s first visit to his homeland, in 1979, shortly after he succeeded to the Chair of Peter. He invoked the power of the Holy Spirit to renew the face of Poland and liberate it from the bondage of communism and atheism.[1] The prayer was transformative.

That is a perfect illustration of what those in power should do. Jesus pointed out that, unlike the Gentile rulers who lord it over their people, Christians must rule through selfless service. ‘Whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be slave of all.’ There is no better example of this than Jesus Himself, who came not to be served but to serve, not to live but to give His life as a ransom for us.

Finally, the Second Reading (Heb 4: 14-16) makes it clear that we must envision the ‘throne of grace’, where Jesus is seated, at the right hand of God the Father. Our High Priest sympathises with our weaknesses, so we can easily draw near to His throne, trusting that we will receive mercy and find grace. Which is so much unlike the earthly seats of power that are hotbeds of inconsideration, corruption and degeneration. Thus, there is not a doubt that only those who have gone through the passion are deserving of the glory.

Banner: The Sagrada Familia Basilica, Barcelona https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sagrada-Familia

[1] https://breakingground.us/we-want-god/

Where to lay up our treasures

We all wish to be happy, don't we? And everything we do is in high hopes of achieving happiness. The problem is when we don’t know what true happiness looks like. We look around and see wealth and possessions, power and influence, health and beauty, fancies and pleasures, knowledge and skills, and mistake them all for happiness. No doubt, they are blessings and they do make us happy; yet something feels incomplete. For sure, when we leave God out of the equation, we fail to balance the formula of happiness.

King Solomon, arguably the author of the Book of Wisdom, states that wisdom clinches it: ‘I preferred [wisdom] to sceptres and thrones, and I accounted wealth as nothing in comparison with her. Neither did I liken to her any priceless gem, because all gold is but a little sand in her sight, and silver will be accounted as clay before her. I loved her more than health and beauty, and I chose to have her rather than light, because her radiance never ceases. All good things came to me along with her, and in her hands uncounted wealth.’

So, wisdom it is that we must seek out so as to attain happiness. Wisdom is the ability to see things, through prayer, the way God sees them; it is a spiritual gift that enables us to discern God’s plan. St Thomas Aquinas says it is both the knowledge of and judgment about ‘divine things’, and the ability to judge and direct human affairs according to divine truth.[1] Like Solomon, when we aim for the sky, all that is under it is ours for the asking: when we seek God – who is Wisdom – the rest is added unto us (Cf. Mt 6: 33).

The rule applies to everybody without exception: parents and children, teachers and students, managers and employees rulers and the people, statesmen and their advisors, scientists and researchers, all professionals, the clergy and the laity, The world will be a better place if we take wiser decisions. Domestic quarrels, public scandals, intercontinental wars are often a result of misinformed or confused minds groping in the dark. Alas, some of them may be downright malicious in what they do, but others simply use the wrong means to achieve their ends. For instance, some may naively think that just having wealth will bring them happiness....

Here is probably where that well-meaning man of the Gospel text (Mk 10: 17-30) failed miserably. He had approached Jesus with an all-important question: ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’ Jesus referred him to the commandments: he had observed them all! Moved by his uprightness, the Good Teacher declared: ‘You lack one thing. Go, sell what you have… and come, follow Me.’ At that saying, the man’s countenance fell; he went away sorrowful, for he had great possessions. That is, his love for money had proved to be greater than his love for God….

It is sad that the man turned away. That line about him speaks volumes about the folly of rejecting a divine invitation and about continuing to wallow in the mire of the world. It is not that we must give up everything and head to the nearest monastery; rather, even while we follow our calling, we ought to be ready to make one heap of all our winnings and never breathe a word about our loss. It must be God’s will all the way, in what we do, wish, say. Jesus has to be the be-all and end-all of our existence; He who is Wisdom Incarnate has to be our supreme ideal!

Does that seem to be a tall order? Nothing is too big for Him who is the ‘Light of the World’ (Jn 8: 12). Let us learn to trust in Him. By our presence and word, let us spread His light and dispel fear from our disbelieving world. ‘Do not worry beforehand about what you are to say,’ says St Mark elsewhere, ‘but say whatever is given you at that time, for it is not you who speak, but the Holy Spirit’ (Mk 13: 11). The Second Reading (Heb 4: 12-13) pertinently notes that ‘the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and spirit.’

After all, wisdom is one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit; and the word of God, like a learned judge, is unyielding. He discerns the thoughts and intentions of the heart, and before him none is hidden. In fact, ‘we are open and laid bare to the eyes of the one to whom we must present an account,’ says the Letter to the Hebrews. So, why dilly-dally? Let us first seek the kingdom of God, discern His plan, and live by it. Wisdom will then bear abundant fruit.

Is the spirit willing but the flesh weak? Don't worry; let our hearts leap with joy on hearing the good news of salvation. The Lord has promised that our detachment from earthly treasures and the enduring of persecutions for His sake will gain us eternal life. So, how about laying up treasures in heaven rather than on earth? And on this day that marks the last Marian apparition at Fátima, let us pray that the good old Miracle of the Sun, which inspired thousands way back in 1917, convinces the world that God exists and that His salvation is for real.

Banner: https://prunedlife.com/lay-up-treasures-in-heaven/

[1] https://www.catholic.com/magazine/print-edition/the-seven-gifts-of-the-holy-spirit

Saving Marriage and Family

In a way, today’s Readings are about the survival of humankind. They dwell on the institutions of marriage and family, both of which are fundamental to society. And society is not a mere collection of physical bodies but of souls, while marriage, family and society are, not humanly, but divinely instituted. Which explains why, in a godless world, marriage and family are the first targets of the evil one. Marriage is demeaned by divorce; family life, by individualism. Both deviations are toxic and can lead to the death of humanity.

The Readings of today could not be clearer. A comment on God’s creation of man and woman comes in the very second chapter of the Book of Genesis. The relevant text which makes up the First Reading (Gen 2: 18-24) highlights that, to make a helper fit for Adam, no beast nor bird was of avail. Finally, God made Eve, a woman, out of the man’s rib, causing Adam to remark: ‘This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh.’

A story we lapped up as children has now become the butt of criticism. In a so-called rational and secular world, are we, then, still to believe the traditional story of creation? Yes, for in the ultimate analysis there is no quarrel between religion and science: truth is one. The Biblical account is not a text of physics or biology all right; it does not have the answers couched in modern-day parlance. Similarly, the Big Bang theory, for example, is just that – a theory! Devoid of clinching evidence, it is at best a scientific story.

That is not all. Theories such as these are likely to remain inconclusive till the end of times, as a vindication of the omniscience, omnipotence and omnipresence of God. In this regard, Cardinal Ratzinger, in In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall, cites Albert Einstein, who said that in the laws of nature ‘there is revealed such a superior Reason that everything significant which has arisen out of human thought and arrangement is, in comparison with it, the merest empty reflection.’[1]

Some may demand to know why God created man and woman in the first place. He did so according to His wisdom and moved by genuine love. ‘God created man in His image; in the divine image He created them; male and female He created them’ (Gen 1: 27) And ‘therefore a man leaves his father and mother and cleaves to his wife, and they become one flesh’ (2: 24). God blessed them, saying, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it’ (1: 28). That was the divine sanction for marriage.

In the Gospel (Mk 10: 2-16) we see how Our Lord was especially attentive to the issue of marriage. The Pharisees, in a bid to test the Divine Master, quoted Moses, who had said it was lawful for a man to divorce his wife. Jesus retorted that the Prophet said so in view of their ‘hardness of heart’, or obstinacy. Then, condemning divorce in no uncertain terms, Jesus said: ‘What God has joined, let not man put asunder.’ The same applies to the family, which is in the throes of an unprecedented crisis created by sinister agencies.

Past Popes, in their encyclicals, allocutions, apostolic exhortations and other documents on the subject, staunchly stood by Our Lord’s teachings. But alas, by and by, the world began to rationalise and relativise those unequivocal teachings. Soon, the purpose of bringing forth new life, through man and woman’s participation in God’s creative love, got thwarted. Gender identity have got reinterpreted and gender roles challenged – yet another form of the proverbially ominous cry of the fallen angels: Non Serviam (‘I will not serve’). It is therefore important that the Church earnestly catechise the faithful on the nobility of marriage and family. Her efforts would go a long way towards reducing the number of annulments (hopefully, not a euphemism for ‘divorce’) granted by ecclesiastical tribunals.

It is a pity that, influenced by evil forces, the modern, rational man keeps making irrational decisions! Some of our sins cry to heaven for vengeance. As for God, in His eternal love for His supreme creation, He sent His Son to the world. Jesus deigned to become lower than the angels – He became man, and ‘by the grace of God tasted death for everyone,’ as the Second Reading (Heb 2: 9-11) reminds us.

Jesus is the New Adam; His Mother, the New Eve. We must turn to them in fervent prayer, to save the traditional institutions of marriage and family: ‘May the Lord bless us all the days of our life’ (Ps 127).

Banner: https://shorturl.at/Apnu2

[1] Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall (1990), transl. by Boniface Ramsey, O.P., p. 23.

God’s Spirit in our Hearts

September 29, 2024Mass Readings

While Moses wished all people were prophets and Jesus welcomes those that are in alignment with His commands, the Epistler St James comes down heavily on the worldly wise, for Heaven is what they risk losing.

The First Reading (Num 11: 25-29), taken from the Book of Numbers,[1] focusses on the string of complaints that the Israelites had about the hardships faced enroute and against Moses. When Moses finally threw up his hands, God directed him to select 70 elders to assist him in governance. At a ceremony held at the Tabernacle,[2] they were filled with Moses’ spirit, following which they began to prophesy. This act prefigured the Sacrament of Holy Orders.

The prophesying of old was replete with exotic and ecstatic manifestations. But the point here is that two elders, Eldad and Medad, who for unknown reasons did not attend the initiation, began to prophesy anyway. Of course, while not all are bestowed the gift of prophecy, God is free to grant it to whoever He deems fit. In other words, ‘the wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So is it with everyone who is born of the Spirit’ (Jn 3: 8).

But that did not prevent jealousy from raising its head. Moses therefore says to his aide Joshua, who was the complainant: ‘Are you jealous for my sake?’ These words can be disturbing if jealousy is equated with envy. While jealousy arises from love of persons or things we possess, envy is sorrow felt about something that others enjoy and we crave for. Interestingly, St Thomas Aquinas breaks jealousy down into ‘love of concupiscence’ (which is selfish) and ‘love of friendship’ (selfless).

To give Joshua the benefit of doubt, we may see his jealousy not as concupiscent, selfish love but as friendship,selfless love. Joshua was not competing with the duo but had objections to what he regarded as insubordination. Joshua’s attitude speaks volumes of his zeal for protocol, love for, respect to and obedience of authority. In our times, we could take this to mean lovingly upholding the perennial Magisterium of Holy Mother Church.

In fact, Joshua’s life was one of discipleship; and after the death of Moses, he led the tribes of Israel in the conquest of Canaan. For his part, Moses expressed the wish that all would receive the gift of prophecy: ‘Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets, that the Lord put his spirit upon them!’ Centuries later, the Christians were filled with the Holy Spirit at the first Pentecost.

That the Gospel text (Mk 9: 38-43, 45, 47-48) should bear a striking resemblance to happenings of some two millennia earlier only goes to show that human nature never changes. When John told Our Lord that he had forbidden a non-disciple from casting out demons in His name, Jesus very simply instructed him to refrain from doing so: ‘Do not forbid him; for no one who does a mighty work in My name will be soon after able to speak evil of Me. For he who is not against us is for us.’

Thereafter, praising innocence like that of a child he was holding, Jesus stated that whoever causes the little ones who believe in Him to sin, ‘it would be better for him if a great millstone were hung round his neck and he were thrown into the sea.’ Strong words, followed up by stronger ones: if one’s hand or foot or eye be the cause of sin, cut or pluck them off, He said – for it’s better to enter heaven maimed than to be in one piece and go to hell.

It is not that Jesus decries institutional or formal arrangements and acclaims informal ones; He only impresses upon His disciples not to be stiff and ‘square’ but, rather, to play it by ear. He urges you and me to set our minds and hearts on Heaven; after all, nothing else matters as much. We have to go about our daily chores happily and fulfil duties to the best of our abilities, but at the same time prize heaven above earth.

In this context, St James the Great in the Second Reading (Jas 5: 1-6) comes down heavily on the wealthy who are charmed by material riches, and, to satisfy their greed, grind the faces of the poor. Once again, sharp words addressed to the likes of them: ‘You rich, weep and howl, for the miseries that are coming upon you… you will eat your flesh like fire.’

One is reminded of Mephistopheles who says sadistically to Dr Faustus in Marlowe’s play of the same name: ’Tis too late, despair, farewell! Fools that will laugh on earth, most weep in hell.’ For sure, none of us wish to be counted among their number. Let us therefore quickly choose to have God’s spirit in our hearts and be at peace with our consciences by fulfilling God’s commands: the precepts of the Lord gladden the heart (Ps 18" 8).

[1] It is the fourth book of the Pentateuch, common to the Torah as well. Its name comes from the two censuses of the Israelites: one taken upon leaving Mount Sinai, and the other, when at the doorstep of the Promised Land of Canaan.

[2] Also called ‘Tent’, it referred to the portable sanctuary that Moses had built to be a place of worship for the Hebrew tribes during the period of wandering before their arrival in Canaan. The arrangement became redundant after the erection of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem in 950 BC.