Outpouring of the Holy Spirit

You will be amazed to see the profusion of Readings on the occasion of Pentecost. It truly parallels the great outpouring of the Holy Spirit! While the Day Mass always has the same text for the First Reading, the Second Reading and the Gospel change cyclically. Besides, there are special Readings for the Vigil of Pentecost: four alternative First Readings, a Second Reading and Gospel that remain constant across the cycles. The Vigil indeed fills us with the joy of anticipation!

Pentecost very well deserves a trumpet blast, as it marks the glorious Birth of the Church. Just as a close-knit family gathers together in excitement even before the arrival of a baby, the Church imagines the community drawing together for the liturgy of the Vigil and virtually waiting on for a different liturgy at the Day Mass. Such is the emotion that goes with any birth, and all the more so with the mystery of our spiritual birth as a faith community.

Let’s begin with the Vigil Readings and note their aptness. Gen 11: 1-9 recounts humankind’s proud attempt to build a Tower that would reach God, and how God punished such insolence by confounding their speech. In contrast, at Pentecost those humble and faithful disciples were rewarded with the gift of tongues, the ability to communicate in languages unknown to them (xenoglossia or xenolalia).

The second alternative Reading (Ex 19: 3-8) refers to the moment when Moses had summoned his people to seal their covenant with the Lord. As he went up the mountain, his people down below witnessed thunder and lightning, a thick cloud and a very loud trumpet blast. This foreshadows the New Covenant given to the disciples gathered in the Upper Room. They too experienced fire and sound at the descent of the Holy Spirit.

The third possible Reading (Ezek 37: 1-14) recalls the valley of dry bones that was enlivened by God’s Spirit. It prefigures the life-giving effects of the Holy Spirit on the spiritual life and mission of His Church.

The last substitute Reading (Joel 2: 28-30) harks back to the time when God promised the Prophet that He would pour out his Spirit upon all flesh, letting people of all ages and ranks prophesy, dream of the future, see visions and wonders. This was fulfilled when the disciples gathered together with the Mother of God in the Cenacle.

And talking of hope, St Paul in the Second Reading (Rom 8: 22-27) utters a paean to the Holy Spirit. He assures us that the Paraclete ‘intercedes for us with sighs too deep for words.’ In this valley of tears, where our life is so full of care and we have no time to stand and stare, when we and the whole of creation groan in travail, the Holy Spirit will renew the face of the earth. When this will happen we know not, but we must contribute to realise God’s Plan.

Finally, in the Gospel text for the Vigil Mass (Jn 7: 37-39), Jesus proclaims Himself as the Living Water. He announced this on the last and most solemn day of the Feast of the Tabernacles, an annual event that remembered the law and the covenant. It was one of the three feasts that the Jews observed, by sprinkling the altar with the waters of Siloam, in remembrance of that which had sprung out from the rocks of Mount Horeb. Post-Pentecost, the water of the Holy Spirit would flow continually.

As regards the Day’s Readings: in two blogposts we commented on that invariable First Reading (Acts 2: 1-11), ('Ecstatic and Fiery': https://rb.gy/y5a7f5 and 'Pentecost and Proclamation': https://rb.gy/4c0p3i ). Now we shall go straight to the Second Reading (Gal 5: 16-25) of Year B. Here, St Paul advises his community to live by the Spirit and refrain from gratifying the desires of the flesh. ‘The Spirit produces love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, humility and self-control.’ On receiving these gifts, so very different from what the world has to offer, we are invited to give up our old ways and live by that gift which has made us new.

Is this possible? The Evangelist (Jn 14: 15-16) quotes from Our Lord’s last discourse, at the Last Supper: ‘If you love me, you will obey My commandments.’ Yet, we are not alone in this divine enterprise; Jesus has promised us a Helper par excellence, the Holy Spirit, ‘who will stay with you for ever.’ The Holy Spirit, whom the Father has sent in His Son’s Name, will teach us everything and make us remember His commandments. All we have to do is believe and trust in Him.

For the Lord’s work to happen through us who are the Church, the Holy Spirit will instruct us opportunely. His outpourings will continue until the end of time.

Ponnji atam mhatari zalea

May 15, 2024Konkani,Goan Literature

Arvind (Ana) N. Mambreachi lhan kotha

Arvind (Ana) N. Mambreachi lhan kotha

Devanagarintlem Romi lipiantor ani Purtugez bhaxantor korpi – Óscar de Noronha

Ponnji: Manddviche deger patllaun boxil’lem hem ek xhar. Hanga motarint pavta. Bosint pavta. Bottint pavta. Bott zalear Ponnjechea sam’ki kallzak tenkta. Ti matxi usram pavli zalear, polasint bhitor sorun mukhel-montreak zap diun magir tumcheani ghora vochum ieta.

Xhar

Ponnji Tiswaddint asa. Tiswaddiche lokvosti sadharonn lakhavoir. Poikim Ponnjent sadharonn satt-ek hozar ravtat. Pavsachea tempar Ponnjent paus khub poddta. Rostear zollim-mollim khatonnam zatat. Passei-hancher xello zata. Punn paim nisrun mat konn poddnant. Karonn Ponnjeche lok toxe toklen fin. Xiam tempar xim khub khata. Punn Ponnjekar kudkuddnant. Fokot gimant kalor khub zata ten’na mat’ te bettech taptat. (Kaloran Ponnjekaranchi xir rokddich titt zata).

Ponnjent rajachi ek polas asa (tika Palácio de Idalcão mhonntat). Ponnjentleo her soglleo polasi Ponnjekarani bandlea. Devulvaddear, Altinho, Santa Inez ani Campalar g-h-e mhonnun polasi asat. Ponnjekarancho poiso soglo tangelea ghorani ani motarini otla. Hangasol’lea choddxea ghorank monxanchim nanvam – Govinda, Sushila, Gurunath, Souza, Mascarenhas, Heera, Prema, Dempo, Velho, oslim.

Ponnjent ghoranchea zoteank nogram mhonntat – Adarshnagar, Neuginagar, Kundaikarnagar bi. Hea disamni don sorkari odhikari devulvaddear ghoram bandtat. Tanchim nanvam – Bhaunagar and Tainagar. Campalar eklo blakist ghor bandta tache nanv – Komagattamarunagar.

Ponnjechea nogramvori nogram akh’khea sonvsarant na mhonnttat. Poir Amerikechea President Ford-an Washingtonak khoim eke election-hache sobhent sanglem, mhaka tumi venchun dixeat zalear tumkam hanv Ponnjechea Kundaikarnagaravori ek nagar bandun ditolom.

Tibluchem ghor

Tibluchem ghor khub lhan. Tantunt monxam him: avoi, bapui ani Tiblu. Tiblu ekloch zolmak ail’lo. Zolmak ietnach ievzupak lagil’lo, ho sonvsar oso kitem? Lhanponnan Tiblu roddonaslo. Khub usram to ulounk lagil’lo. Ulounk laglo tori to uloinaslo. To fokot ievjitalo. Vachtalo. Boroitalo. Chitram kaddtalo. Uloi mat’ naslo.

Roste

Ponnjent roste bore xekan’xek patoll’leat. Ponnjeche lokamvori Ponnjeche roste-i bore susegad-xe. Disbhor jemet astat. Ponnje eka rostear choltanach monis dusrea rostear pavta. Ponnjechea pattear bhitor soril’lo monis soroll cholunk lagot zalear João Castro - José Falcão - Dada Vaidya rosteavelean bodh Ponnji sompta thoim pavum ieta. Hea rosteanchi ekuch bori gozal mhollear Ponnjechea lokank zati-kati-dhorm lagtat te tankam lagonant. Hea rosteanchea nimitant Dada Vaidya, dotor Atma Borcar, Shirgaonkar he babdde Afonso de Albuquerque, Cunha Rivara, Bénard Guedes, Governador Pestana hanche pongtik bosunk pavleat. Ponnjent 5 October, 18 Jun, 31 Janer oslei roste asat. 31 Janer ani Rua de Ourém hanchemodim il’lexem ek Portugal asa ani Devulvaddear ek supul’lo-so Maharashtr asa.

Lok

Ponnjek lambai-rundai bori asa. Punn itleim asun Ponnjekaranchi monam sam’kim oxir. Toxe Ponnjent sogle toreche lok asat – bore, vaitt, sadhe, xanne, pixe, sadhe-bore, bore-bore, xanne-bore, pixe-bore, sadhe-xanne, sadhe-pixe, xanne-xanne (dedd-xanne), pixe-xanne. Hanga vepari, blakist, professor, dotor, advogad, ijiner, oxetoreche-i lok ravtat. Mineir mat vhoddlexe nat. Punn je asat tanchebogor her lokanchem paul ukholna. Dil’lintle sogle montrilegit tankam vollkhotat.

Tibluchem vachop

Tibluk lhanponnapasun vachpacho nad. To ghorant zollim-mollim bosun vachtalo. Bhailea humrear, randche kuddint, iskadesokla, magildara. Tiblucho bapui bolkanvant ontorraxtrik rajkornnacher bhasabhas kortalo ten’na Tiblu khoimtori khanchi-konnxak bosun chitram kaddtalo.

Zantto zatokuch Tibluk konnetori mhollem, Tiblu, tum laibrorint kiteak vochonam?

Tibluk tea monxean Sorosvotimondir dakhoilem. Tedischean Tiblu thoimsor vochun bosunk laglo. Sokallim iskolant vochop. Jevop-khavop, abheas korop, chea ghevop. Magir laibrorint vochop. Bodh ratcho attank ghora portop. Jevop-khavop, chitram kaddunk bosop. Il’lo il’lo korun Tiblu borounk-ui xikil’lo. Kovita korunk lagil’lo…

Nanvam ani zati

Ponnjent eka nanvache, dotti nanvanche lok khub. Poi, Bholo, Poi-Bholo; Duklo, Bhobo, Duklo-Bhobo; Bhobo, Kakulo, Bhobo-Kakulo; Souza, Paul, Souza-Paul; Kamat, Ghanekar, Kamat Ghanekar; Sequeira, Nazareth, Sequeira Nazareth. Khottkhotto, Zingddo, Buttulo, Buddkulo, Topanxett oslei monis Ponnjent ravtat. Ekach nanvache hanga khubxe lok melltat: Dotor Costa, Professor Costa, Advogad Costa; Professor Nadkarni, Advogad Nadkarni, Dotor Nadkarni; Dotor Boddko, Advogad Boddko, Professor Boddko. Konnso mhonttalo, Santa Inez oxetoren 15 Desai (Sardesai dhorun), 12 Kamat ani 9 Nayak ravtat.

Svotantrataiepoilim Ponnjent donuch zati asleo – poixekar ani Ponnjekar. Mineir, blakist, vepari, empregad he sogle poixekar. Her sogle Ponnjekar. Mhollear Bahujan-samaj. Svotantrataie uprant hatunt anik don zatinchi bor poddli – montri ani deputationist. Poinkim deputationist hi scheduled caste.

Ponnjeche montri khub uloitat. Zai title uloitat. Naka titlei uloitat. Ponnjekarancheo sobha montreambogor zainant. Montreanchem pavl sobham bogor ukholna. Sadharonn montreanchem uloup oxem asta:

Janten hem korunk zai.

Janten tem korunk zai.

Janten soglem korunk zai.

Sogle Ponnjekar (poixekar ani Bahujansamaj) montreank khub lekhtat. Tantle tantunt poixekar tankam chod lekhtat. Adlea kallar zanche hat Purtugez rajeakorteomeren pavil’le tanche hat atam montream-meren pavleat.

Ponnjent man koro tigank: montreank, montreanchea parentank ani montreanchea vollkhicheank (hantunt sezari aile). Uprant sorkari odhikoreank. Montreank zaum odhikoreank zo vollkhona to Ponnjent sandloch.

Xinu

Xinuchi pirai 60 vorsam. Tachem borem chol’lam. Vepar, min, blak, rajkaronn… to sogleant asa. Hachem ghevop taka divop ho tacho vepar. Zachem ghetlam tachem naddear to min kaddta. Zaka dilam tachea malvozar to blak korta. Zachem ghetlam ani zaka dilam taka gheun to montreanger ani amdaranger favtti marta. Sod’deache assemblintle don montri ani dha amdar aple, Xinuchem mhonn’nem.

Sonstha

Lions Club, Rotary Club, Junior Chamber, Goa Chamber of Commerce, Konkani Bhasha Mandal, Marathi Sahitya Sevok Mandal, Bhagini Mandal, Mine Owners Association, Exporters’ Association, Indo-Soviet Cultural Society, Rose Society, Vivekanand Society… kitleosoch sonstha. Chear Ponnjekar ektthaim ailear panch sonstha kaddtat. Hangasol’lo ek-ek monis dha-dha sonsthancho membr asta. Ponnjentle khubxe vhodd monis hea sonsthanche membr. Hangsol’le lhan monis vhodd monxancher uloitat. Vhodd monis odik vhodd monxancher uloitat. Sorkar jantecher uloita.

Ponnjent vhoddlixi janta na. Dispotti ji hanga janta dista ti bhailea ganvsun – Merxe, Kalapur, Raibandar, Tallganv – ail’li asta. Ken’na-ken’nai ti Kansavli, Kolvall, Divaddi, Pednem, Sall, Bannavli hangacheanui ail’li asta. Khasa Ponnjent ji il’lixi janta asa ti Molleant, Bhatleant bi ravta. Poixekar Altinho, Campalar ravtat. Ponnjecho Devulvaddo ani Santa Inez hanga donui toreche lok ravtat.

Altinho eka kallar fokot vhodd monisuch ravtale. Atam thoim montri, sorkari odhikari ani pixe-i rautat. Montri ani poixekar motarani bhonvtat mhonnun her monxapasun te matxe veglle distat.

Lions Club, Rotary Club hancheo sobha sodam vhoddlea hotelamni zatat. Konkani, Marathi mondollancheo sobha lhan’xe kuddani zatat. Te club ganv poske ghetat. Monddolam vorsbhor sompil’lea sahiteakanche zolmdis ani mornndis manoitat. Reformad sorkari empregad vell pasar korpakhatir hea kareavollink ietat. Vivekanand ani Rose sosaitianchea songit kareavollink/prodorxonank mat sogle Ponnjekar bail-bhurgeank ghevun vetat.

Tibluchi dairi

Poir igorjechea festak mhaka Xinudaad mell’lo. Khub uloilo. Chaitr punvechea nattkant aplea putak part mell’la mhonnun sangtalo. Mhaka mhonnunk laglo, ‘Tum kitem korta?’ Hanvem mhollem, ‘Chitram kaddtam, kovita boroita.’ To mhonnunk laglo, ‘Video kiteak vikina?’

Nustem

Baki Ponnjekarank nusteabogor zaina. Bazarant nustem borem ieta. Sungttam, moteallim, vel’leo, pedve, balle, korchanneo, mudd’doxeo, xenvtalleo, kallundram, sorgem, bangdde, xenvtte, kol’leo, moreo, sangttam, visvon, gobre, tisreo, khube, xinnaneo … Soglem tea tea tempar ieta. Punn sogleank tem ghevop zomona. Sogle bazarant dispotte nustem haddunk mhonnun vetat. Bhitol’le orde tem mharog uzo mhonnun viktem ghenastanam porte ietat. Horxim ho ‘uzo’ poixekaranchea ghoramni dispotto pett’ta.

Nustem khavun, nhid kaddun, uttun, chea ghevun Ponnjekar sanjche passeik vetat. Zanchekodden motari asat te Miramar vetat. Zankam pai asat te Campalar vetat.

Devull and igorz

Hanga ek devull ani ek igorz asa. Ponnjentle poixekar sou dis patkam kortat ani satvea disa devullant, igorjent vetat, oxem her Ponnjekaranchem mhonn’nem (korem fot, Dev zanna!). Hi gozal khori asot zalear dusri-i ek gozal titlich khori. Tea devullantli ani te igorjentli – dogui saibinni – tankam tanche guneanv bhogxitat.

Devull Mahalaxmichem. Hea devullant amorechea vellar dive lagtat. Te dive polloun Professor Borcaran ‘Tethe kor mhaze jullti’ oxi ek kovita boroili. Ani akh’khea Maharashtrak ti khub’ manouli. Ten’nachean sogli Marathi janta tankam Kovi Borcar mhonnun vollkunk lagli… Hi khobor devullachea manddapantlea sopear bosun ek Ponnjekar dusrea Ponnjekarak sangta. Ani tea vellar devullant purann cholta.

Tibluchi dairi

… atam hanv korum kitem? Mhaka vachop zomona. Chitram kaddop zomona. Kovita korop zomona. Vetam thoim lokancho kochkoch. Bovall. Laibrariank legit atam tintteanchem rup ievunk laglam. Paddpoddil’le he lok ghorcheo gozali thoim ievun kiteak kortat, hanv nokllom, bovall… bovall… bovall… Soglekodden bovall… Hanv vachpakhatir zago sodunk laglom. Kitleaxea lokamni mhaka kitleoxoch suchovnneo keleo (baki Ponnjekar suchovnneo korunk huxar!). Konn mhonnunk laglo, Campalar voch. Konn mhonnunk laglo, Miramar voch. Raibondarchea pattear… Merxeche vatter… Altineachea dongrar, mosnnant, fonddant… Sogleamni sogle zage sangle. Ek dis hanv Altinho bismache polasikoden vochun boslom. Thoim ek padri ailo. Mhonnunk laglo, hea sonvsarant soglem k-u-i.

– Mhonttokuch hanv kitem korum?

– Tum pustok vachunk hinga kiteak eilai?

– Khoi vochum tor?

– Simiterint. Tinga tuka kosloch bobav aikunk ievpacho na.

Tedischean hanv Santa Inez simiterint (mosnnant mhonnunk borem disona) vochun bosunk laglom.

Turist

Ponnjent turist khub ietat. ‘Dona Paula sundor disto’ mhonntat. Konnui muddaxekar dislear, ‘ha bogha Goveacha mannus’ mhonnun bott dakhoitat. Uprant barramnim vetat. Ani piye piye pietat.

Xinu sodanch mhonnta, hanka chorank jite marunk zai. He Mumboiche dollidri lok hanga ievun amgeli Ponnji padd ghaltat, tachem mhonn’nem. Teaporos te hippie bore. (Tanchekoddlean Xinuk bhorpur foren jinam, lugttam, goddeali, keseti bi melltat).

Simiterint Tiblu

… Atam Tibluk tanchi sonvoi zalea. Sonxebaab, Hundirmam, Bangdde Porob, Pandu Fott’to, Vitu Sawant, Xedd’do, Visvonn, Boklo, Doddearo, Vonibai, Tai-bai… sogleanchim bhutam tachekodden loktubaien uloitat.

Poir Sonxebaab boro talar ail’lo. Tibluk mhonnunk laglo, hanv tea vellar melom mhonnun suttlom. Nazalear tujechvori jivak vittlom aslom. Ponnji mhonntat ti atam sam’ki vitt ievpasarki zalea. Hanga he mosunddent tori ken’nai boro varo ieta. Bodh Purtugezanchea tempar Ponnjent golltalo toso. Toso varo ailo mhonntokuch mon sam’kem khoxi zata! Oxem dista to babddo Salazaruch sorgantsun ho varo amkam dhaddinam mum?

Sonxebaab huddkea-huddkeani roddunk laglo. Tiblu bienlo. Dolle motte korun aikot ravlo. Sonxebabak Tibluchi kakullot aili kai kitem konn zanna? Roddop tharavn thoddea vellan to mhonnunk laglo: – ‘Tiblu, papea, soglo ganv soddun tum hanga mosnnant dispotto kiteak ieta?

– Pustokam vachunk, Tiblunk biet biet zap dili.

– Pustokam vachun tum kitem kortolo?

– Mha… mhaka vhoddlo monis zavpacho asa.

– Mhojem aikotolo?

– Aikotam. Sang!

– Rajkornnant bhitor sor.

– Ani kitem korum?

– Gõycho mukhelmontri za.

– Kiteakiteim kitem sangta?

– Bhau mukhelmontri zalo. Tai mukhelmontri zali. Atam Babu mukhelmontri zatolo. Tea adim tum mukhelmontri za. Adim zomlem na zalear uprant za. Punn zolmant ek favt tori Gõycho mukhelmontri za ani jivitachem kalyann korun ghe! Tathastu!!

Tedischean Tiblun vachop soddlem…

The Real Ascension Story

Who would not believe a supernatural occurrence like the Ascension just because he has not witnessed even a pale resemblance of it? While today’s First Reading (Acts 1: 1-11) and Gospel (Mk 16: 15-20) describe the physical event, the Second Reading (Eph 1: 17-23) offers a theological interpretation. The bottomline is that in time those believing in the Lord of the Ascension will also enjoy the same experience.

We must bear in mind that everything about Jesus was supernatural – right from His joyful Birth to His luminous Transfiguration, sorrowful Passion and Death and glorious Resurrection. Unprecedented events they surely were, but always witnessed by many and duly recorded for posterity. In fact, in stitching together details from the evangelists and other writers, we note that differences in minor details make their narratives complementary, not contradictory. So, modern men and women ought not be sceptical but ever more trusting and believing.

Forty days in Galilee

The Ascension came about at the end of Jesus’ forty-day stay in Galilee following His Resurrection. In keeping with a prior promise, Jesus opted for that region (about 125 km away from Jerusalem) only to avoid a potential clash with the Sanhedrin. The Jewish supreme council was waiting to pounce on the newborn Church that was proclaiming their Risen Lord from the rooftops.

How did Jesus spend those forty days? He appeared several times to the Apostles, ‘in ways that proved beyond doubt that He was alive’. Once, at the iconic Lake Gennesaret, he surprised them with a miraculous haul. He was thus a provider of material goods to His inner circle whom the traitor Judas Iscariot had robbed of their kitty. But more importantly, Jesus was a provider of spiritual food. Taking the Eleven aside, He would decipher the hidden meanings of His public discourses.

Jesus also took care to set up a second line of leaders. By asking Peter to feed His lambs (beginners in the faith) and sheep (those more mature in the faith), He virtually handed over His baton to the future Pope. Furthermore, to meet His disciples at once, he bade them gather at a mountain nearby. Was it here that Jesus once appeared to more than five hundred (probably from across Jerusalem, Judea and Galilee)? If so, this could well be regarded as the first Council of Christendom!

Were they upbeat about meeting Jesus? When He appeared in flesh and blood, the Apostles fell on their feet in worship, whereas some others doubted. Nonetheless, Jesus moved forward, commanding them to go and teach all nations, baptising in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. ‘Teach them to keep all things that I have commanded you, and lo! I am with you all days, even to the consummation of the ages!’ he assured them.

When the day of his departure was close, he met with the Apostles in Jerusalem. They were probably preparing for the Shavuot[1]. There, at His last meal together, He instructed them not to leave the city of David until they had received the Holy Spirit. He showed how the references to Him in the Scriptures – in the law of Moses, in the prophets and in the Psalms – were unfolding.

Then, Jesus rose up and led them to the Mount of Olives. The Apostles followed enthusiastically, believing that He was going to restore the political dominion of Israel. Alas, the more Jesus spoke to them of Heaven, the more they dreamt of life on earth! Our Lord retorted: ‘It is not for you to know the times and seasons which the Father has fixed by His authority. Enough for you to know that the Holy Spirit will come upon you, and you will receive strength from Him; you are to be My witnesses in Jerusalem and throughout Judea, in Samaria, yes, and to the end of the world.’

How ashamed the Apostles must have been for broaching inanities! They walked on in silence, until they came to the top of the hill. There, Jesus lifted up His hands to bless the Apostles. And while He did so, He was seen rising body and soul above the hilltops and fading into the firmament. Tradition has consecrated this site as the Mount of Ascension and Christian piety has memorialised the event by erecting a basilica over the site. An octagonal structure thereabouts, now used as an oratory, encloses the stone said to bear the imprint of the feet of Christ.[2]

Our Ascension

Needless to say, the Apostles were awestruck. Two angels in shiny white garments addressed them: ‘Galileans, why are you standing here looking up at the sky? He who has been taken from you into heaven will come back in the same way that you saw Him go to Heaven.’ So, they went back full of joy to Jerusalem, praying, praising and blessing God.

What about us? What does the Ascension mean to us today? In one of his Ascension homilies, Pope John Paul II said: ‘In the Scripture readings, the whole significance of Christ’s Ascension is summarised for us. The richness of this mystery is spelled out in two statements: Jesus gave instructions, and then Jesus took his place.’[3]

Jesus had instructed the Apostles to speak explicitly about the Kingdom of God and about salvation. The early Church clearly understood the instructions and the missionary era began and will not end until the same Jesus, who went up to heaven, returns. His words are a treasure for the Church to guard and to proclaim. In the words of thenow canonised Pontiff, ‘Our greatest challenge is to be faithful to the instructions of the Lord Jesus.'

About Jesus taking His place at God’s right hand, the Pope quotes his predecessor Leo the Great, who once remarked that ‘the glory of the Head became the hope of the body.’ That is to say, from His throne of glory, Jesus sends out to the Church a message of hope and a call to holiness. ‘The Church may indeed experience difficulties, the Gospel may suffer setbacks, but because Jesus is at the right-hand of the Father the Church will never know defeat. Christ’s victory is ours.’

Jesus is no longer physically present on earth but He is eternally alive and in our midst through the Holy Spirit. Thanks to Him, Heaven and Earth have drawn closer, such that ‘the efficacy of Christ’s Ascension touches all of us in the concrete reality of our daily lives.’ Our Ascended Lord participates in our toils and sufferings. He who entered the world through the Incarnation and returned to the Father through His Ascension wishes to save us for eternity. His Ascension is a prelude to the ascension of believing humankind. That’s the ultimate Ascension Story.

[1] The single most important event in Israel’s history, commemorating the handing of the Torah, or Pentateuch, to Moses at Mount Sinai.

Love and Salvation

Achieving peace of mind and heart is probably the one goal common to all of humankind. We live for it, and we even die for it. Happiness is all we seek, except that we sometimes use the wrong ‘search engines.’ And that makes all the difference. Ends do not justify the means; and at other times, not even knowing what our ends should really be is confusion worse confounded.

It is sad when we make of our life on earth an end in itself. We live as though our days will stretch out for ever and are blank on our eternal salvation. That is when Biblical posers like ‘What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his soul?’ (Mk 8: 36) makes us jump out of our skin. This has happened to so many who have gone before us – perhaps, most famously, to St Francis Xavier, whose date of arrival in Goa we commemorate tomorrow.

However, if we care to have the mind of Christ, we will not only appreciate the divine plan but also have our own perspective plan in line with it. His plans are based on love – because ‘God is love’, as St John puts it very plainly in the Second Reading (1 Jn 4: 7-10). Love is the very essence of God, and ‘he who loves is born of God and knows God, and he who does not love, does not know God,’ says the Beloved Disciple.

Further down in the text (not part of today’s Reading), the Epistler says, ‘No one has ever seen God, but if we love one another, God lives in union with us, and His love is made perfect in us.’ (1 Jn 4: 12) No doubt, some, like Moses, have seen God face to face, but as to the rest of us, since our physical eyes can perceive only the physical, even if in a limited way, we need to make a spiritual effort to see God, a spiritual and invisible being, with our mind’s eye.

We will never fully understand God, let alone see Him. And love: do we know how that works? Love is an overused, nay, abused word, whose true meaning is outlined by the Catechism of the Catholic Church (§§ 733, 1766, 1829, 2658). Love has been examined times without number by philosophers and poets, saints and sinners, yet few have done it justice. Meanwhile, the celebrated Catholic writer C. S. Lewis speaks of Affection, Friendship, Eros and Charity, in his book The Four Loves. He bases himself on the Greeks who distinguished between storge, philia, eros and agape, and demonstrates how very often they quite imperceptibly merge into each other.

Accordingly, affection or storge is familial love, or the ties we have with whoever and whatever we consider our very own. Friendship or philia covers those who we are naturally attracted to by the values we share. This is different from Eros, a passion primarily understood as sexual, but which could also be of an aesthetic or broadly (not necessarily holy) spiritual nature. Lewis discerns the deceptions and distortions that could well render these three natural loves dangerous if devoid of the sweetening grace of Charity or Agape, the divine love that must be the sum and goal of all.

Where do we find the supreme example of divine love? ‘God so loved the world that He gave His only Son, so that everyone who believes in Him might not perish but might have eternal life’ (Jn 3: 16). The Letter to the Hebrews puts it vividly: ‘In the past God spoke to our ancestors through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by His Son, whom He appointed heir of all things, and through whom also He made the universe’ (Heb. 1: 1-2). In effect, while Jesus has redeemed us of our sins, by His supreme example of love, He has also made God visible and accessible to us.

For His part, Jesus said: ‘Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’ None that have claimed to be God ever did so, except Jesus, who died for our sake. That catchy line from today’s Gospel (Jn 15: 9-17) is followed up by a command: to love one another as He has done and to bear abiding fruit. What better way to set that love in motion than going out into the world and proclaiming the Gospel? As we see from the First Reading (Acts 10: 25-26, 34-35, 44-48), ‘God shows no partiality, but in every nation any one who fears Him and does what is right is acceptable to Him.... The gift of the Holy Spirit has been poured out even on the Gentiles.’

You and I are called to be instruments of God’s love, by giving witness to all, including the non-Christian world, as Peter did at the house of Cornelius the Centurion. We must not do anything in fear or for personal gains, but simply persevere in love; we need not worry about how we are to speak or what we are to say, for that will be given to us at the right time. Our love, sincere and self-sacrificing, must reflect God’s love. This will serve as evidence that God truly exists and that His Son is the Lord of our eternal salvation.

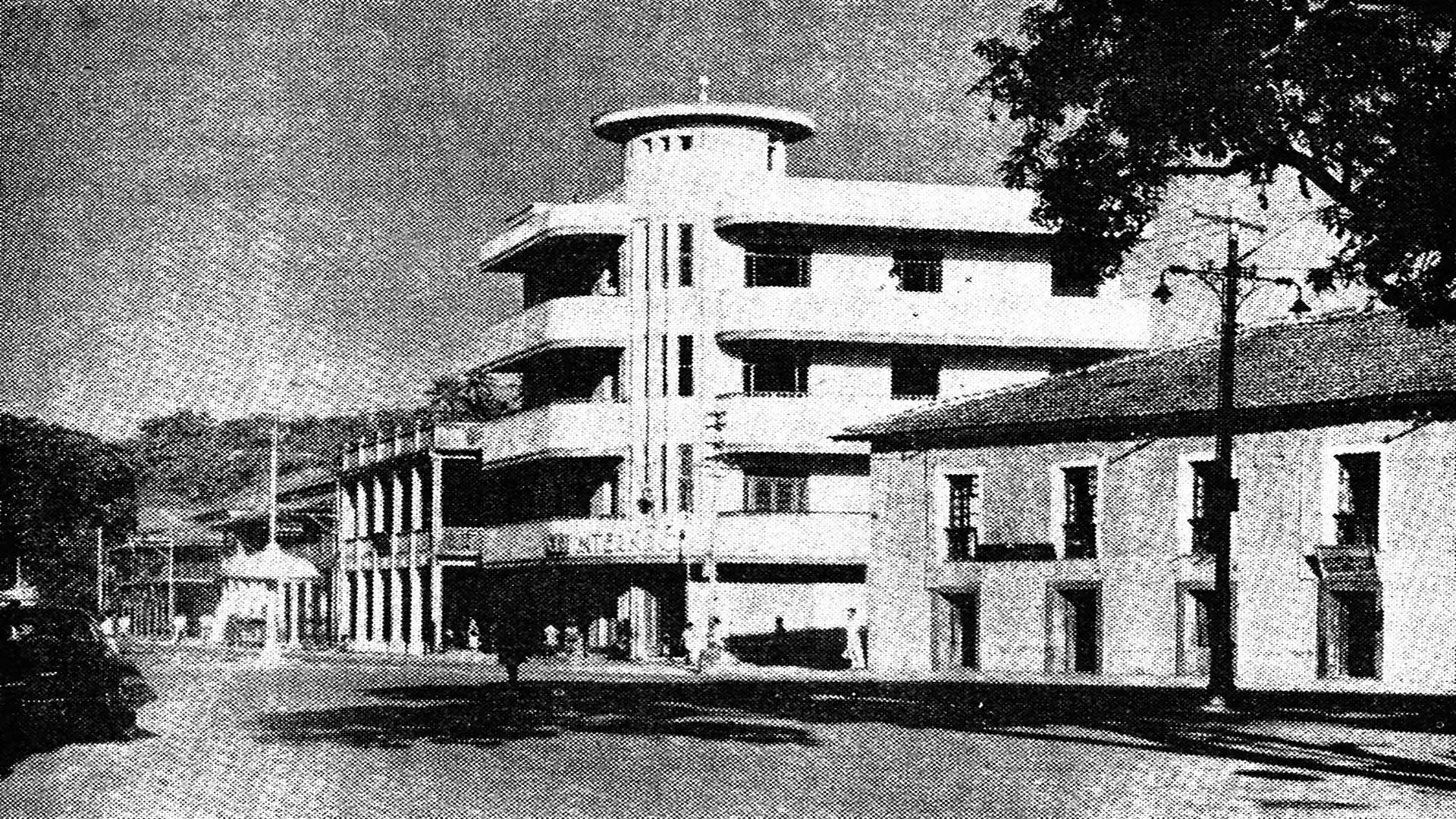

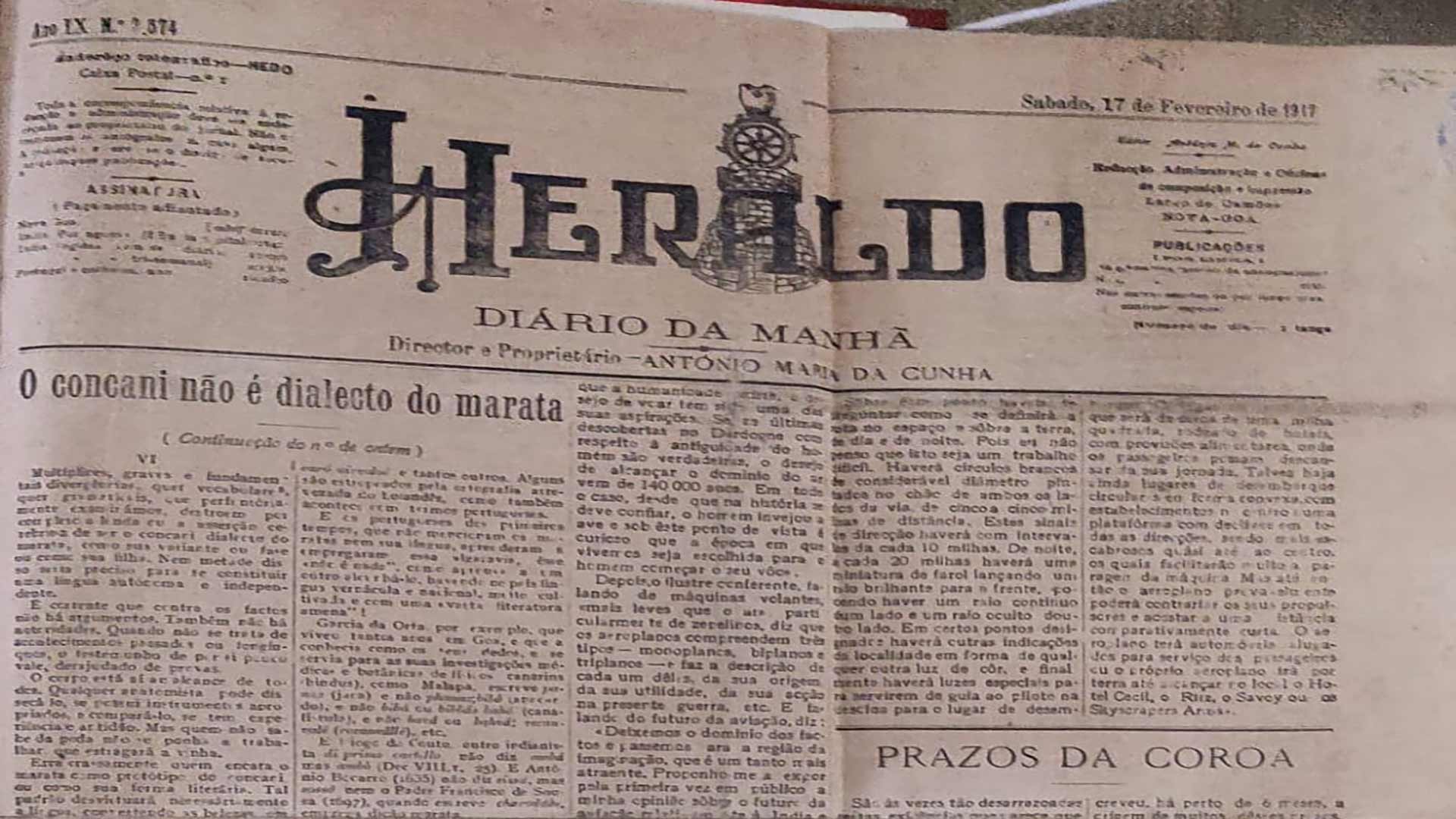

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 6

Part 6 of “O concani não é dialecto do marata”, by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado,

in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2574, 17 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

The multiple, grave and fundamental divergences, both in terms of vocabulary and grammar, which we have perfunctorily examined, completely destroy the legend or fanciful assertion that Konkani is a dialect of Marathi, as its variant or phase, or as its daughter. Not even half of this would be necessary to constitute an autonomous and independent language.

It is said that against facts there are no arguments. Nor are there authorities. Unless it has something to do with past or distant events, testimony alone is of little value, if devoid of proof.

The body is there within everyone's reach. Any anatomist can dissect it, if he has the right instruments, and compare it, if he has experience and aptitude. But those who know nothing about pruning should not get into it, lest they spoil the vineyard.

It is a gross mistake to view Marathi as prototype of Konkani, or as its literary form. Such a pattern will necessarily distort the language, turning beauties into snags – as some Gongorists did in the past, with clumsy results – a monstrous amalgam. This should not be repeated in the future. With such an orientation and teachers, you can forget about cultivating Konkani. Let the language be!

Recently, it was stated that Konkani has been in existence for only about four hundred years, thus insinuating that it was a creation of the Christians. How cold-bloodedly can Goans make such audacious and paradoxical statements! Did they by any chance attend the délivrance – as they call it there, and it will not be long before they say ‘Our Lady of Bonne Délivrance’ – or at least have its birth certificate?

Prodigious Christians! They have invented a speech grammatically superior to Marathi and closer to the Prakrits and to Sanskrit!

And the amazement moves up another notch if we imagine how they imposed it on the Hindus in Goa and on the natives who went from here to as far as Bombay and Cochin, where I got to converse with a goldsmith in the said language!

Furthermore, the Hindu Brahmins who worked with Rheede on the Hortus Malabaricus (published in 1678) did not issue him a certificate in the ‘vernacular and literary’ language – Marathi – but in that monstrous Konkani; and the names that they gave to the plants were not taken from that ‘beloved daughter of Sanskrit’, but from its ‘nameless corruption’, namely: cudó, colassó, caló-dotiró, caró-nirvoló and many others. Some of them are marred by the convoluted orthography of Dutch, and the same is the case with Portuguese terms.

And the early Portuguese, who mention neither the Marathas nor their language, learned and used this gibberish, this ‘nothing’, as someone else chose to dub it, even while the country had a very developed vernacular and national language with a ‘vast and enjoyable literature’!

For example, Garcia de Orta, who spent many years in Goa, which he knew like the back of his palm, and who for his medical and botanical research took help from Kanarese (Hindu) physicians such as Malapa, writes panaj (jackfruit) and not phanaz; bibó (anacardium) and not bibá or bibbás bahó (canafistula), and not bavá or bahvá; rezanvalé (rozanvâlle), etc.

Similarly, Diogo do Couto, another Indianist di primo cartello, does not say ambá but ambó (Déc. VIII, I, 25). And António Bocarro (1635) does not say sissá, but sissó, nor does Father Francisco de Sousa (1697) employ Marathi diction when he writes charoddós.

Even the English were bewitched by this ‘unqualifiable dialect’, since it is in Konkani, and not in Marathi, that they looked for the origin of certain terms they used. Hobson-Jobson derives patamar from the Konkani, in the sense of ‘mail and vessel’: ‘In both senses the word is perhaps the Konkani path-mar, “a courier”.’ And as regards buckshaw, mentioned by Fryer, Hamilton and Grose, Yule writes: ‘“Little fish of any sort.” This is perhaps the real word’. Clearly, there are Konkani dictionaries that, in the opinion of the foreigners, deserve to be perused. And our scholars do not bother to read them, because they are not ‘comme il faut’. Good pretext for lazybones, no doubt: Language, why do I want you?

The last of the abovementioned words is indeed registered without its etymology, in my dictionary, under the forms bavxem and bapxem, and meaning ‘small fish, minnow’. But there will be always be a Konkanist emeritus who will declare that such a word does not exist, because he has not heard it, and that the dictionary is worthless. Jesus Christ forgot to include among the beatitudes: Beati ignari, qui sapientes se ostendunt! It is always more elegant to be a master than a disciple; it is more comfortable to teach than to learn.

Abiding with God

Today’s Readings make it clear that all is well when God is with us. But what about us: are we always with Him and for Him? Being on God's side may seem a natural thing, but we do reject Him sometimes, don’t we? Sin is to blame. It causes us to disbelieve. Hence, a turnaround is always in order and can make all the difference.

That is how it was in the life of Saul. In the First Reading (Acts 9: 26-31), we see how his life changed on his way to Damascus, in a personal encounter with the Risen Lord. Given his poor track record, however, the Apostles did not regard him as a disciple. Until Barnabas put in a word for him. He told them how Paul had boldly preached Jesus in the capital of Syria. In an about-face, Saul had become Paul.

‘Great things happen when God mixes with us,’ says a hymn. ‘Some find life, some find peace; some people also find joy…. Some see their lives as they never could before/ And some people find that they must now begin to change.’ That was the story of Paul too: he found life, peace, joy. Above all, he found the need to change. Enriched by special charisms, he argued among the Hellenists (Greek-speaking Jews), and eventually became one of the greatest spokesmen for Christ.

Meanwhile, St John in the Second Reading (1 Jn 3: 18-24) stipulates that love of God ought not to be limited to word or speech; it must be seen in deed and in truth. It is vital for love of God to translate into love of neighbour. Not a cakewalk, though. Very often, we only act civil and camouflage our bitterness. Worse still, if we do it for self-gain. Plain-speaking or forthrightness is preferable; it may make us vulnerable, but then, we have nothing to hide – or lose – anyway, do we?

It goes without saying that love must not be self-centred but God-centred. But to think that we can love by ourselves is an illusion; we can do so only with God's help. Human beings are selfish by nature, and trying to love neighbour before we learn to love God is like chasing an impossible dream. The fact is that mutual love would come more easily if everyone made an effort to put God before self. We cannot stress enough how God has to be at the centre of our attention.

To make God the be-all and end-all of our life, it would be ideal for members of our community to share the same understanding of Him. This is possible if we all seek the truth and are duly instructed. Proper catechesis would go a long way towards making up for heterodox ideas gaining currency in our midst. The world would find it easier to accept Jesus as our only Saviour, if Christians readily bore witness to Him. After all, Jesus has proved His Divinity. His Resurrection is the bedrock of our faith. Against this fact there can be no argument nor authorities or testimonies devoid of counterproof.

Earlier in the Easter season Jesus said: ‘I am the Bread of Life’ (Jn 6: 35); ‘I am the Light of the World’ (Jn 8: 12); ‘I am the Door’ (Jn 10: 9); ‘I am the Good Shepherd’ (Jn 10: 11, 14); ‘I am the Resurrection and the Life’ (Jn 11: 25); ‘I am the Way and the Truth and the Life’ (Jn 14: 6) – and in today’s Gospel (Jn 15: 1-8), He says: ‘I am the Vine’ (Jn 15: 5). He is the Vine; His Father, the Vinedresser; and you and I, the branches of the Vine. Every branch that bears fruit is pruned by the Heavenly Father that it may bear more fruit; every other that doesn’t, he takes away.

Thereafter comes a clincher: ‘He who abides in me and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from Me you can do nothing.’ To abide in Him we have to be clean, be pruned of all our imperfections; to abide with Him means to keep His commandments. It is one thing to be patient towards those who have not had exposure to Christian doctrine; it is quite another to be complaisant towards those of our flock who consciously offend God, be it in words or deeds. Many mock Him openly, others adopt irreverent postures. This calls for some fraternal correction, or else, of love there will only be the shell.

St Paul calls us to be all things to all people. Yet, we must never act against moral principles merely to love others or be loved by them. It is futile to love others out of human respect (excessive regard for their opinions or esteem). No person is worth sacrificing a principle for; and it is ‘better to take refuge in the Lord than to trust in princes.’ Even a morally good act is meritorious only if done because it follows God’s law and is intrinsically good. In fact, only when human law is united with divine law, and human love with divine love, can divine life penetrate human life. That is when we will truly abide with God and He in us.

Ever faithful, never mute

Post-Easter Readings have a special freshness and power conveyed by the Holy Spirit. No matter what their perception of Christ earlier, the apostles now are fully convinced that He is the True God. Maybe they had looked at Him merely as a provider of material goods, be it bread or physical cures; they had failed to see Him as the spiritual provider – the Way, the Truth and the Life. By now they – and we too – know better.

The First Reading (Acts 4: 8-12) builds on what we read last Sunday. Peter, in treating a lame man, attributed the cure to the power of Jesus. Peter and John were still speaking in the Temple when some priests, the officer in charge of the temple guards, and some Sadducees got them arrested and jailed. When questioned by the Sanhedrin, Peter charged his countrymen with killing Jesus, whom God then raised from death. That the dead will one day rise to life was anathema to the Sadducees.

Peter went on to relate the present happenings to the Scriptures: ‘The stone that you the builders despised turned out to be the most important of all,’ said Psalm 117. He reiterated that salvation is to be found through Jesus alone; in all the world there is no one else who can save us. This was surely more than the self-righteous authorities could bear to hear. Understandably, those words also refer to God’s infinite love and to how ‘it is better to take refuge in the Lord than to trust in men.’

This is clearly a reminder that we have to repurpose our life in the light of what Peter has said. In the Second Reading (1 Jn 3: 1-2), his co-apostle John calls upon us to consider ‘what love the Father has given us’. Had He not loved us with a fatherly love, would He have sent us His Son Jesus? By the Incarnation and the Supreme Sacrifice on Calvary He showed us that He loved as His very own. Hence, we ought to be faithful. The fruits of our faithfulness may not be visible today, but ‘when He appears we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is.’

The practical implication is that in every circumstance of our life we must turn our eyes heavenward for an answer. God works in and through us. Whereas the spirit of the world will always be antithetical to the spirit of God, it is of the essence that we keep the faith. When the Son of God returns, everything will become clear as day. The veil covering our immediate reality will be removed and we shall appreciate our glory as children of God. The once frolicking children of the world will then appear as children of darkness.

In fact, for those who have eyes to see and ears to hear, this is not rocket science. In a world teeming with life coaches and leaders of all kinds, all of them promising the moon but failing to deliver, today’s Gospel text (Jn 10: 11-18) calls to mind a most tender image of a caring God who promises absolute love and care and delivers it. To put it in context, Jesus had just cured a man blind from birth. When the temple authorities found him acknowledging the Son of Man, they summarily expelled him from the synagogue. It prompted Jesus to deplore the sin of spiritual blindness – the refusal to acknowledge God. And to give the man solace, Jesus presented Himself as the Good Shepherd. The Fourth Sunday of Easter is therefore called 'Good Shepherd Sunday'.

By this, Jesus evoked a scene that every Jew was familiar with: the self-sacrificing nature of a shepherd worth his salt. A good shepherd defends his flock against enemies, keeps watch over them and shuts himself up with them at nightfall. At dawn, he counts their number and leads them safely to fresh pastures. While he is with them, he now and again utters a shrill call; recognising his voice, the scattered sheep huddle around him. For sure, a stranger’s voice enticing them will not receive the same response, for the flock recognise him not.

Such is the case of every authentic shepherd and his flock. In a broad sense, the shepherd could be a parent, teacher, elder, counsellor; the sheep would be the children, students, youngsters, and those in need of counsel. Above all, it is the image of the church. The Pope is recognisably Jesus’ supreme representative on earth; he is the shepherd, we the flock. As much as the Pope is obliged to be a good shepherd, we are called to be good sheep. Jesus was also concerned about ‘other sheep that are not of this fold'; in His words, 'I must bring them also, and they will heed my voice, so there shall be one flock, one shepherd.’ The Pope has to do likewise. Together, we can build the Church, which is the Mystical Body of Christ. This is a mission in which the sheep must help their shepherd.

On the other hand, he who is only a hireling and not a shepherd will leave the sheep to the wolves and flee, for he cares not for the sheep. What, then, are we to do as sheep? We must be wary of false shepherds. And if by some misfortune the shepherd becomes a wolf, we the flock must defend ourselves.[1] As a community, we must shed our inhibitions, our goody-goody image. Aren’t we taught elsewhere in the Bible to ‘be shrewd as a serpent, yet innocent as a dove’ (Mt 10: 16)? So, both shepherd and sheep must stand up, speak up. We are called to be ever faithful, never mute.

Goencheo Mhonn'neo - VII | Adágios Goeses - VII

April 17, 2024Sayings and Proverbs,Goan Literature

Segue uma sétima lista de adágios,[1] extraídos do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (1872-1935)[2].

Concani | Tradução literal | Tradução livre

Dhazananchó sangat corsó nãy, ani coroddachyá ujyak chekuchém nãy. | Dha zannacho sangat korcho nhoi, ani koroddachea ujeak chekuchem nhoi.

Não tome todos como amigos,

(pode não dar bom fim,)

como também nunca se aqueça

ao fogo do capim.

Pantçuy bottâm sarquim nãy. | Panchui bottam sarkim nhoi.

Não tem igual dimensão

os cinco dedos da mão.

Toda a personalidade

não tem a mesma habilidade.

Sunyanchi chemp noliyênn ghalyar passunn, sarky zay na.| Suniachi chemp nollien ghalear pasun, sarki zaina.

O rabo de um cão

que é torto, se o ajeita,

pondo-o ainda num tubo,

nunca se endireita.

Torna-se impossível

corrigir quem de índole

é incorrigível.

-o-o-o-

[1] Cf. sexta lista, Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 26, janeiro-fevereiro de 2024, p. 43.

[2] Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda, Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), com acrescentamento dos adágios na grafia moderna, pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 27, março-abril de 2024, p. 47)

Glow of the Resurrection

The more we think of the crisis of faith and morals in Jesus’ times, the better we understand our own. Our prayer should therefore be that we appreciate the Easter message. It throws the spotlight on the glory of the Resurrection, which is not a mere symbol but a reality, the bedrock of our faith.

Public support for Jesus began to snowball after the Resurrection. Our Lord was at work every day, through the marvellous acts of the Apostles. Peter came out particularly strong. He had the glow of the Resurrection. As today’s First Reading (Acts 3: 13-15, 17-19) indicates, he continually testified to Jesus. While he charged his countrymen with the heinous crime of killing ‘the Author of Life, whom God raised from the dead,’ he made allowances for their frailty and exhorted them to repent.

What about us? Do we draw hope from the Resurrection and the scope for repentance? In her Apparitions worldwide, Our Lady stressed that the world has greatly offended Her Son. We laypeople have done so by our indifference, not to say deliberate silence, always expecting the authorities to set the tone and show the way. Meanwhile, in ecclesiastical governments – as it has long been in civil too – the tables have been turned. Sadly, matters of faith and morals have become a worldwide cobweb. And caught up in their own webs, lawmakers and enforcers have become lawbreakers and perverters.

The Church is thus at the crossroads. We Christians had better bear witness to Christ or perish. At present, seduced by the world, many – be it priest, politician or people – seem to be trying it the other way around: brazenly counter-witnessing to save their skins… In the process we let the Mystical Body of Christ be targeted, wounded, mangled... all in the name of forgiveness and tolerance! May the first Pope’s words pierce into the deepest recesses of our hearts, for hell is most likely bursting at the seams: ‘Repent, therefore, and turn again, that your sins may be blotted out, that times of refreshing may come from the presence of the Lord.’

In the Second Reading (1 Jn 2: 1-5), Christ’s Beloved Disciple makes an equally fervent appeal: ‘I am writing this to you so that you may not sin.’ His assurance that Jesus Christ the righteous is ‘the expiation for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of the whole world’ emboldens us indeed. But then again, let us not put God to the test; let us quickly and sincerely work towards a change of heart and mind.

The Epistler goes on to warn his people: ‘He who says, I know Him, but disobeys His commandments is a liar, and the truth is not in him; but whoever keeps his word, in him truly love for God is perfected.’ To help us truly love God and to perfect the law, which the Sanhedrin had corrupted, was the purpose of Jesus’ coming to the world. We need Jesus to come again and do away with that new Sanhedrin taking root in our beings, in our homes and workplaces, in our schools and communities; and we must not let it be embedded in our Church. It would mean crucifying Our Lord and His Bride yet again. Down with such a Sanhedrin!

The point is that we need to renew our encounter with Christ! From the Gospel (Lk 24: 35-48) we realise that Emmaus is our daily beat after all! Christ walks with us, but we fail to notice Him; He daily bears our burdens, but we do not acknowledge the fact; He continually talks to us, but we answer not. And what if He should show us His hands and His feet nailed for our sake? Would we wake up from our slumber and gird ourselves, or feel troubled and faint?

'Lift up the light of your face on us, O Lord's (Ps 4). Let the glow of the Resurrection remain with us forever. May our spiritual renewal, fired with the spirit of the Resurrection, help us proclaim the Good News of Christ our Lord to the world!

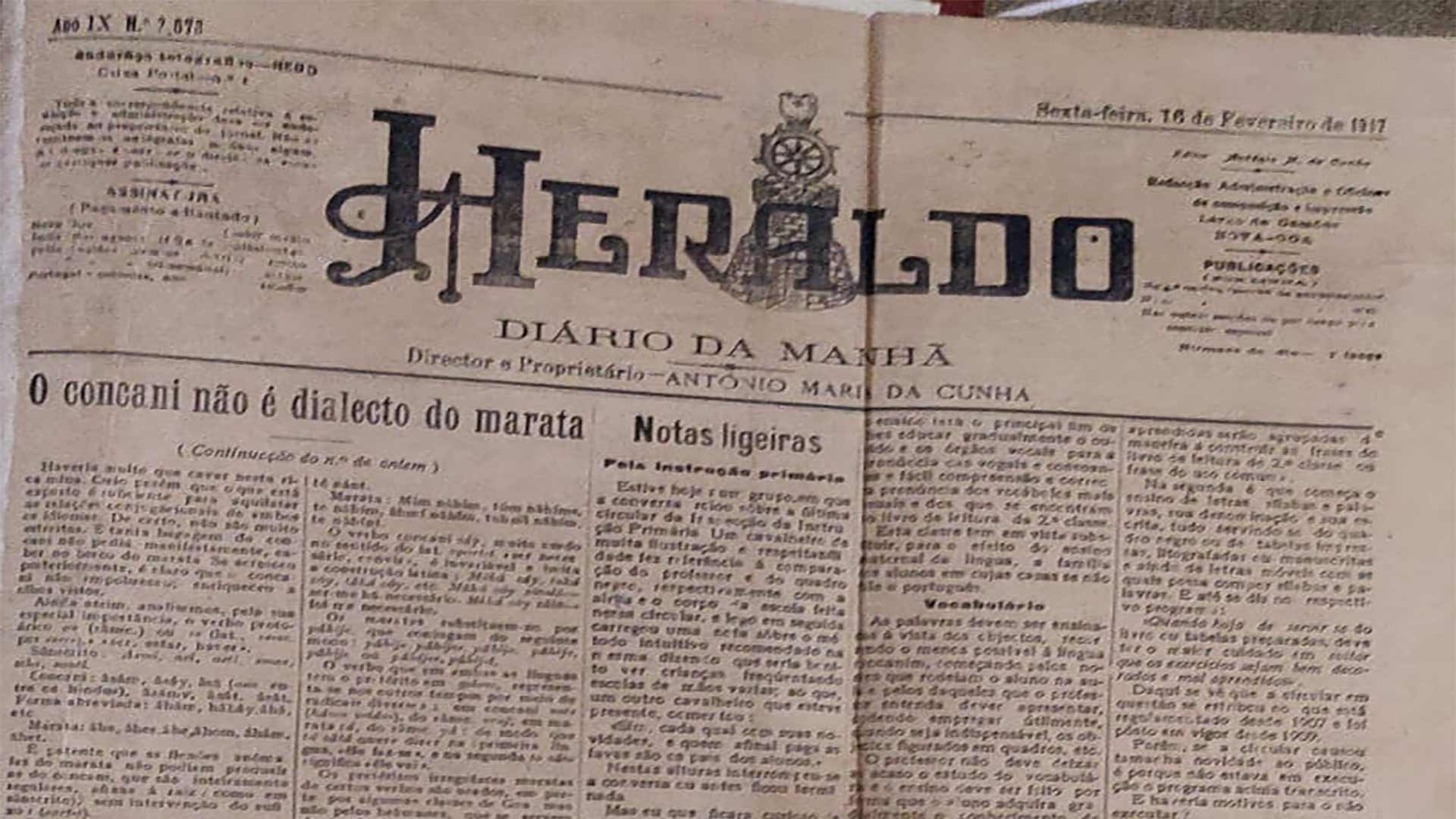

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 5B

Part 5[B] of “O concani não é dialecto do marata”, by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado,

in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2573, 16 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

There is a lot more to dig in this rich mine. I believe, however, that what has been laid out here is sufficient to understand the conjugational relations between the two languages. For sure, they are not very close. And so much of Konkani’s baggage definitely would not fit into the Marathi boat. It may have got bigger later, but surely Konkani was not the poorer for it; it rather got perceptibly richer.

Even so, given its special importance, let us analyse the Indo-European verb as (Sansk.) or es (Lat., es-se for es-re), to be, to have.

Sanskrit: Asmi, asi, asti, smas, stha, santí.

Konkani: âsám, âsáy, âsá (asa, among the Hindus), âsámv, âsát, âsát. Abbreviated form: âhám, hâháy, âhá, etc.

Marathi: âhe, âhes, âhe, âhom, âhám, âhet.

It is obvious that the anomalous flexions of Marathi would not produce those of Konkani, which are entirely regular, affixed to the root (as in Sanskrit), without the intervening suffix t (sart-t).

The past tense in Konkani uses the base as: âslom, âsloy, etc. That of Marathi is: hotom, hotás, hotá, etc. That is a huge difference – toto coelo – and does not discredit Konkani.

Another Sanskrit verb, jan (3rd p. pres., jâyate), to turn, to become, to get (French, devenir) passed on to Konkani in the stem zá (zátam, zátáy, zâtá), and is conjugated regularly in all tenses. Marathi, on the other hand, uses the said verb only in the past tense (jhâlom), replacing it, in the rest, with the verb honnem, derived from the Sanskrit bhû, which has given rise to the Lat. fu-i.

It is obvious, then, that these are not despicable minutiae that can be easily explained as ‘the degeneration of Konkani taken to extremes.’ On the contrary, they are fundamental divergences, and the aforementioned verbs are so too. It is rightly said in Konkani, when one hears nonsense: Tujé jibek hadd na munn borem âsá: You’re lucky that you don't have a bone in your tongue, or else it would break. And another popular saying goes as follows: Tuka jib nasli zâlyár kavlle tonchún kâtelé âslé: if you had no tongue (the only sign of life), crows would peck and eat you (as if you were a corpse).

Let us also compare the flexions of the same substantive verb to be in the Romance languages, so that the comparison highlights the inconsistency of the detractors of their own language, which they have never cared to study.

Latin: Sum, es, est, sumus, estis, sunt.

Portuguese: Sou, (archaic som, sam), és, é, somos, sois, são (archaic, som) [I am; thou art; he/she/it is; we are; ye/you are; they are]

Castillian: Soy, eres, es, somos, sois, son.

Italian: Sono, sel, è, siamo, siete, sono.

French: Suis, es, est, sommes, êtes, sont.

Is there less affinity between these flexions than between the previous ones? And yet, to this day no one has dared claim that one of the said languages is a corruption of the other. And according to an English proverb (may everything pay homage to the alliance!): What’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

Let us now compare the negative forms of the aforementioned verb as:

Konkani: Hámv nám, túm námy, tó nám, ámím nâhv, tumim nánt, té nánt.

Marathi: Mîm nâhîm, túm nâhíms, to nâhím, âhmí nâhim, tuhmi nâhim, te nâhínt.

The Konkani verb záy, often used in the sense of the Latin oportet, it is necessary, it is proper, is invariable and mimics the Latin construction: Mâká záy, tuká záy, táká záy, etc. Mâká zây zataló = it will be necessary for me. Mâká záy zâló = it was necessary for me.

Marathi uses pâhije, which they conjugate as follows: pâhije, pâhijes, pâhije, pâhije, pâhije or pâhijes, pâhijet.

The verb that in both languages has the past tense in gelom is represented in the other tenses by means of various radicals: in Konkani, vats (hámv vetám), from the Sansk. vraj; in Marathi, zá, from the Sanskrit yá: such that in Konkani tó zâtá means ‘he becomes’, and in Marathi to zâto means ‘he goes.’

The irregular Marathi past tenses of certain verbs are used, partly by some social classes of Goa, but not by the Brahmins, who use it otherwise: Ghetlem = ghelem (regular), was taken; dhutlem = dhulem (reg.), was washed; pyâlem = piyelem or pilem (reg.), was drunk; mâgitlem = mâglem (reg.), was asked for[i]; ghâtlem = ghâlem (reg.), was put; mhanttlem = mhannlem (reg.) or mhullem (by assimilation), [was said]; khâllem = khelem (khâlem would be regular), was eaten.

I could have expanded on this arid and, for many, boring matter, tackling particles and syntax, but I think it is pointless. As regards the former, it will suffice to note that many of them differ from language to language or take diverse forms. Some of them in Marathi are used only by certain classes in Goa; which may be due to ethnic relations. It is a matter more closely associated with lexicology than with grammar; and the comparison is not tough.

Properly speaking, the syntax of modern Indo-Aryan languages has few essential differences. Sentence construction and agreement are almost the same. However, Marathi and Konkani vary a lot in the manner of forming propositions; in ‘our language’, it is more concise, cohesive and elliptical. Here are some examples, taken from Navalcar's Marathi grammar: Râma ânni tyâtsá bâp âle âhet = Râmá âni tâtsó bâpúi áylé: Rama and his father have come. Durgá ânni Sâvitri hyâ bahinni hotyá = Durgá áni Sâvitri bahinnyó: Durga and Savitri are sisters. Janoji va tyâchi báyko kutthem gelim âhet = Janoji âní tâchî bâyl khaim gelint? Where have Janoji and his wife gone? Vaidyânem tilá auxadh deún barem kelem = Vaizan tiká okhat diún bari keli (agreement difference): The doctor cured her by giving her medicine. Mim tum’chyá gharim udyám yein = Hámv tum’ger phalyá yen or yeyn (I may come) or yetalom = I shall come: I shall come to your house tomorrow.

Those interested can easily make other syntactical comparisons, for example, between a catechism in Konkani and Marathi. Rest assured that one will learn a lot about the disparity of the two languages and be convinced – if any more arguments are necessary – that Konkani is not the same as Marathi.

-o-o-o-

[i] Dalgado’s says ‘foi bebido’, which is obviously a typo; it should read ‘foi pedido’ [was asked].

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 27, March-April 2024, pp 38-41)