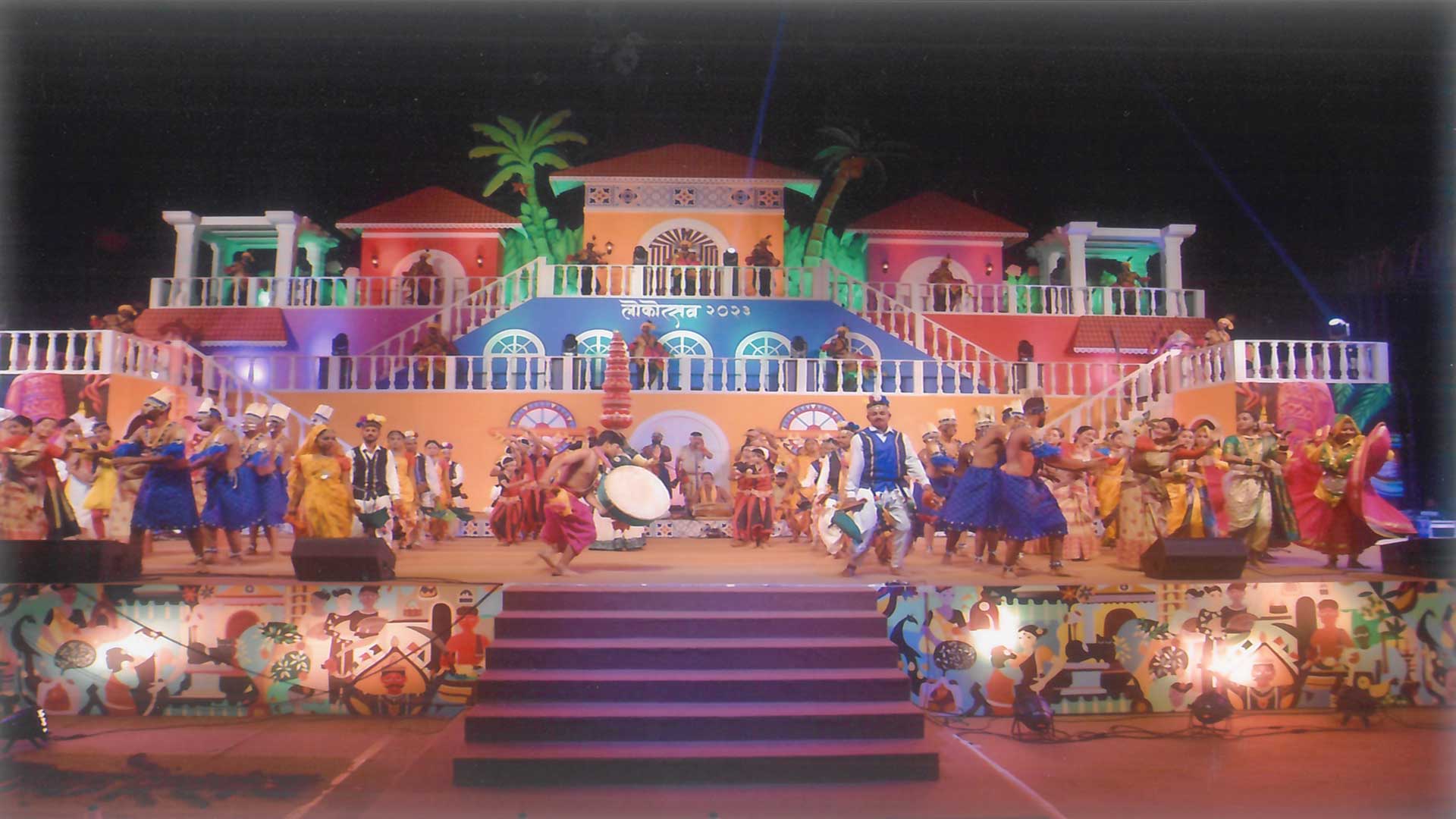

An Enigma called 'Padre Álvares'

BOOK REVIEW | Óscar de Noronha

Saint Alvares Mar Julius, by George K. Kurian. Goa: St Mary’s Orthodox Syrian Church, 2013. Pp 168. ₹ 80.

It does not seem like there is anyone today who has known him personally, for he died over a century ago. Those who did remember him, in the years gone by, usually spoke in hushed voices, given his anti-establishment posture; but even his severest critic would admit that he had a heartbeat for the voiceless in Goan society.

Born António Francisco Xavier Álvares (Verna, 29/4/1836), he studied at Rachol Seminary and was ordained a priest in Bombay (the episcopal chair in Goa was vacant). On his return, he set up a charitable society to rehabilitate beggars (some of whom lodged with him in his rented apartment in Panjim) and a church-aided school. Quick to reach out, especially when deadly epidemics raged in the capital, he once personally saved labourers trapped in a landslide triggered by hill cutting.

The focus of George K. Kurian’s book (Figure 1), however, is the unprecedented entry of that Roman Catholic priest into the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. Until his early public years, Fr Álvares was a conservative and loyalist to the point of defending Portugal’s Padroado rights; what, then, was really the tipping point?

Kurian points a finger at Archbishop António Sebastião Valente’s objections to the tenor of Fr Álvares’s writings in the local press (pp 53, 81); but alas, he stops short of identifying the genesis of his unease, which predated Valente’s arrival in 1882. Over a period of 18 years (1877-1895), the cash-strapped Fr Álvares came to be associated with a number of periodicals (A Cruz; A Verdade; O Progresso de Goa; The Times of Goa and Brado Indiano), in different capacities. Whether or not his politically minded associates and/or funders rode piggyback is a moot point.

Similarly, the author states that the Catholic Church in Goa excommunicated Fr Álvares (pp 75, 158), but provides no proof in support of the claim. It was more likely an excommunication that the priest incurred automatically (latae sententiae), as per the Code of Canon Law, as a result of his entry into the Malankara church in 1887.

At any rate, the purpose of an excommunication is to call a person to change behaviour, repent, and return to full communion. But none of that happened. Instead, in 1888, Fr Álvares went on to form the Independent Catholic Mission of Brahmavar, Karnataka. Was this in response to the Padroado-Propaganda Fide imbroglio?

The rest is history. In 1889, Mar Dionysius, who headed the Malankara church, appointed Fr Álvares to a specially created episcopal post of Metropolitan of Goa, India (excluding Malabar) and Ceylon. Titled ‘Mar Julius’, he still said Mass in Latin (his Syriac and Malayalam were not up to par), catering to the Indian Orthodox Church’s Roman Catholic lay entrants, who were permitted ‘a separate rite and liturgy’ (p. 62). He highlighted the antiquity and authenticity of Antioch vis-à-vis Rome (p. 91) and criticised Western cultural practices in vogue in Goa as against the preferential status that Indian traditions were given in Malabar (p. 54).

In the period 1887-1911, Fr Álvares divided his time between Ceylon, Kerala, Brahmavar and Goa (pp 63, 71). In 1890, the Goa police booked him for unauthorised use of ecclesiastical vestments (p. 111), but the court, on taking cognisance of his episcopal status, acquitted him. On a later visit to his native land, he championed the use of indigenous products (‘a forerunner of the great Swadeshi Movement’, p. 95) and found himself in a spot for denouncing the powers-that-be. He was ultimately charged with sedition and arrested for inciting the Maratha sepoys and Ranes through his writings (p. 113). The court exonerated him (which speaks volumes about the justice delivery system), but Fr Álvares fled yet again, fearing reprisals.

In 1911, Fr Álvares was at the receiving end of a feud between the Patriarch of Antioch and Mar Dionysius (p. 87). It was as if life had come full circle when, excommunicated for siding with the latter, he relocated to Goa and stayed in the same old, ground-floor apartment off Ourém Street. The big difference now was that the Republicans were in power in Portuguese India; but was that why the Malankara archbishop left his domain in Karnataka?

It would be interesting to know what Fr Álvares thought of that secular (read anticlerical) regime, other than that he was left in peace. This time around, he set up an English-medium school and made a plea for primary education in Konkani (p. 78). While in the past he had very relevantly published booklets on the treatment of cholera, presently he advocated large-scale cultivation of manioc as a solution to Goa’s food crisis. Finally, in the evening of his life, devoting himself entirely to charity work, he actually went out with a begging bowl.

Not surprisingly, the longest of the book’s 18 chapters is titled ‘A True Missionary’, which speaks about Fr Álvares’ apostolic work, his associates and the expansion of the Malankara church in India and abroad. The last few chapters describe the final days of this ‘martyr and saint’; his funeral; long-standing friendships; tomb at St. Inez Cemetery; and the formation and work of the Orthodox Church in Goa. Kurian notes that the Roman Catholic Church’s efforts to win Fr Álvares back were in vain. The dying priest insisted that if not the Orthodox Church, his friends alone would bury him (p. 118). He died at Ribandar public hospital (23/9/1923).

The topic of retired bureaucrat George K. Kurian’s self-published volume is intriguing no doubt, but more rigorous editing would certainly enhance clarity and coherence. It is a pity that instances of repetition, typos and grammatical errors detract from the overall reading experience. The book was originally written in Malayalam and is a work of love. The author even took the trouble to include a family tree of the Álvares, besides photographs of the priest and pages of Diário da Noite and O Heraldo, two dailies that covered the funeral and aftermath. All in all, the book helps get a glimpse of the enigmatic figure of Padre Álvares/Mar Julius.

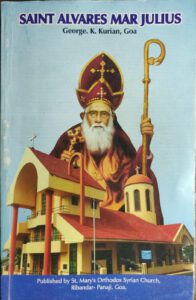

Culture between the Covers

Goa’s culture has long been in the public eye. It has drawn the attention of travellers, academics and statesmen. Some have been quite the culture vultures, lapping up just about everything; others have woven theories, looking at parts to the detriment of the whole; and yet others have just milked the culture dry. The culture-scape is thus fraught with risks. The real work lies in valuing this composite culture, hearing the voice of the local stakeholder, and not letting the golden goose die.

Goa’s culture has long been in the public eye. It has drawn the attention of travellers, academics and statesmen. Some have been quite the culture vultures, lapping up just about everything; others have woven theories, looking at parts to the detriment of the whole; and yet others have just milked the culture dry. The culture-scape is thus fraught with risks. The real work lies in valuing this composite culture, hearing the voice of the local stakeholder, and not letting the golden goose die.

Celina de Vieira Velho e Almeida in Feasts and Fests of Goa: The Flavour of a Unique Culture has claimed her voice. She has documented many of her land’s cultural expressions, based on field work and published material. Her translating sources in Portuguese, updating ethnographic data with contemporary testimonies, and sharing backstories has added value. Missing, however, is a critical introductory essay, which could have provided an apt backdrop to Goa’s culture graph.

The book’s alliterative title could be misread as repetitious. Contextually, however, we may distinguish between a ‘feast’, as a day commemorating a saint or a sacred mystery, and a ‘fest’, as a broad-based celebration. Besides, ‘fest’ in the local Konkani is a corruption of the Portuguese festa, which has both religious and secular connotations. No doubt, most religious feasts in the Christian liturgical calendar are quiet, spiritual affairs; so, not all feasts are fests, even if merriment be the ‘in’ thing in a modern, desacralized setting.

Each of the book’s seventeen chapters maps a feast or a fest. The feast of the Epiphany (at Verem, Chandor, Cuelim) and that of Our Lady of Safe Port (Santa Inez, Panjim) are wholly religious events. The latter is the book’s sole city-based feast and happens at the parish level; the former, with all the countryside fanfare, has acquired a folkloric character. Maybe folksier are the chapel feasts at Pilerne, Siridão, Nerul, and the church feasts at Talaulim and Curtorim: their fairly recent, multicultural dimension has turned them into veritable fests.

Pilerne’s feast of Candelaria is now better known as Kottianchem (Coconut Shell) Fest; Siridão’s feast of Jesus of Nazareth, as Pejechem (Rice Gruel) Fest; and Nerul’s feast of St Anthony is Tisreanchem (Clam) Fest. Ironically, of Curtorim’s Kelleam (Banana) Fest, coinciding with the parish feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, only the name remains; the fruit is conspicuous by its absence. In striking contrast, at Touxeanchem (Cucumber) Fest held at Talaulim’s Santana parish church, one of the finest specimens of Indian Baroque architecture, touxem is a votive offering. Childless couples and matrimonial hopefuls come and say a prayer to St Anne, in Portuguese.

Cultural metamorphosis is perhaps best exemplified by São João, generally mispronounced as Sanjanv. Calling it ‘a Portuguese folk festival’ may suggest that it was transplanted to Goa root and branch, but that was not the case. The life of St John the Baptist so fired the popular imagination that the liturgical feast took on a life of its own, both in Portugal and in Goa. The same could be said of the carnivalesque Potekaranchem Fest, or so-called ‘Shabby’ Festival, held three days before Ash Wednesday, on Divar Island.

Celina Almeida traces the origins of pre-Christian festivals too, thus covering Goa’s Hindu and, perhaps underexplored, Muslim past. She labels Mussol Khel [Pestle Dance] ‘a unique celebration of Chandor Kott’s [fort area] history in dance form.’ The rice pounding festival, symbolic of thrashing the enemy, which formerly took off from a temple, now starts with prayers at a chapel. This, however, is not the only festival to have absorbed Christian elements. Syncretism is the leitmotif of Zagor, a night vigil conducted to placate the gods and ancestral spirits; typified here by Siridão’s Gauda tribe, some of whose Christian members relapsed into Hinduism decades ago.

Proud of the peaceful coexistence of Goa’s many communities, the author makes no value judgements on religious orthodoxy, or the lack of it. She says that Cuncolim’s Sontrio (Umbrella Festival) rooted in the worship of Hindu goddess Shantadurga ‘appears to hold sway over both the major communities in the village, viz. the Catholics and the Hindus.’ Similarly, she considers village Surla-Tar’s Shigmo festival ‘a beacon of Hindu-Muslim communal harmony in Goa.’ In this springtime festival, a dance troupe from Siddheshwar temple visits a dargah and a mosque; Hindus and Muslims exchange gifts, and a maulvi participates in a Hindu ceremony.

While the author urges fellow Goans to make culture relevant to future generations, she lashes out at the authorities for their venality, rampant in the tourism and environmental sectors. She hails Chikal Kalo, organised in the predominantly Hindu village of Marcela, as the world’s only mud festival with religious underpinnings. She acclaims Curtorim’s Handi (Dyke) Fest as ‘a celebration of their contribution to the preservation of water’. The long, eco-friendly tradition of this largely Christian village is evident from its five natural reservoirs and reputation as Saxtticho Koddo (Granary of Salcete).

Two chapters of the book unwittingly pay tribute to the family as an institution. Panjim-based Mhamai Kamat family’s Anant Chaturdashi, centred on the story of a rare conch of religious import, illustrates how one household can animate an entire community. Further, in ‘Ladainhas of Goa’, the author reminisces about the litanies held at her maternal grandparents’ home in Utorda. In fact, even at wayside crosses, where multilingual prayer and singing is a given – and so are those boiled grams garnished with grated coconut washed down by feni or light beverages – litanies could easily be a feast or a fest!

Feasts and Fests of Goa, replete with information of interest to both local and diasporic Goans; excellent colour photography, map, glossary and bibliography, lets the reader experience ‘the flavour of a unique culture’. The book features celebrations held in a little over fifty per cent of Goa’s talukas, leaving ample room for a sequel. The author exudes love for the land and its culture just as naturally as our people did in former times. Hopefully, this will inspire the rest of us to be vocal – and, more importantly, the powers-that-be to take the right steps – in this fast-paced, globalised world, lest our culture be relegated to just between the covers.

FEASTS AND FESTS OF GOA: THE FLAVOUR OF A UNIQUE CULTURE

FEASTS AND FESTS OF GOA: THE FLAVOUR OF A UNIQUE CULTURE

Celina de Vieira Velho e Almeida

Panjim: Self-published, 2023.

Pp 105. PB. Rs 1200/-

Konkani Saga in the Roman Script

The Konkani language is written in many scripts. Ricardo Cabral’s latest offering, Konkani in the Roman Script: a Short Grammatical Study, is a welcome addition to the limited bibliography on the subject. It maps out Konkani’s saga from the time Roman script made an entry into Goa, in the sixteenth century; and more importantly, the book earnestly proposes a modified script.

Before elaborating on the historical “Romanization process”, Cabral looks at fragments of the linguistic history of the mull Goenkar (original natives): the Gauddas and Kunnbis living around the foothills of the Verna-Nuvem plateau. Stating that “the first dialect that has to be taken note of is the Gaudda/Kunnbi dialect”, the author goes on to list its salient phonetic and syntactical features.

Konkani developed a complex structure comprising dialects from the North (up to Malvan) and South (up to Mangalore), with Antruzi, Kunnbi, Shashti, Bardezi and Koli forming the central group. As a result of the immigratory waves from the north and south of the present-day territory of Goa, different dialects of Konkani got integrated down the centuries. That was the position at the time the Christian missionaries began what would turn out to be a grand linguistic enterprise. The Jesuits and the Franciscans naturally chose to write in the Roman script, which was common to Portuguese, Latin and English, and was easier to print.

Cabral traces three developmental phases of Konkani in the Roman script: first, what he calls the Eureka phase, “when all things for the foreign missionaries were objects of wonderment” (16th-19th centuries); then, the middle or Bombay Blast phase (end of 19th to mid-20th century), for the then British Indian metropolis was the nerve centre for Konkani productions in the Roman script; and finally, the modern, consolidation phase (mid-20th to early 21st century). Noting that it was not simple for the missionaries to transcribe the sounds, much less standardise the orthography, Cabral gives examples of how writing in Konkani evolved from being heavily dependent on Latin and Portuguese phonology to trying to find an independent script in contemporary times.

It is not clear why Cabral titles the second chapter “Etymology” when it deals with word or lexical classes as in a traditional grammar. Verbs are then treated more in detail in the third chapter; and it is only in the fourth chapter that we catch a glimpse of the alphabet. It is not always easy to find apt English examples to illustrate sounds in Konkani; quite understandably, the pronunciation chart of vowel-and-consonant sounds in Konkani (ê; fuloi) and their respective phonetic illustrations in English (say /eɪ/; ‘boy’ /ɔɪ/) has a few mismatches.

Whereas the phonetic transcription of some Portuguese words needs to be revisited (e.g. fixo is not /fikso/ but /’fiksu/), the author is right about how hard and soft sounds can make or break. For instance, in church and elsewhere, readers and speakers often fail to distinguish between killo and kil’lo, mellem, mel’lem and mell’lem. Cabral’s table of allophones thus comes across as a valuable learning aid for a language loaded with a variety of phonemes and graphemes.

The general reader is sure to enjoy the chapter on word formation. Cabral elaborates on three types of Konkani words: primitive, derived and loaned. ‘Reduplication’ is an interesting, largely onomatopoeic, process that Konkani words have undergone, giving us picturesque words like khoddkhodd (shivering), davon-davon (hurriedly), poishean poiso (every paisa), and so on. Cabral gives a sprinkling of loan words from Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Kannada, Portuguese, French, Marathi, English, Tullu and Hindi. However, the cited ghurghuret (water pot) is not originally a Konkani word but corrupted from the Portuguese gorgoleta.

In chapter six, ‘Morphology’, Cabral lists hyponyms, homonyms, homophones, polysemes collocations, and so on. And whereas in chapter seven, we find a conventional treatment of Syntax, with a good dose of illustrations, the subsequent chapter tackles a relatively new area: Generative Grammar. Cabral deserves credit for the structural analysis undertaken, by devising much needed test-frames for sentences and tenses in the language. It is a brave effort to modernise the grammatical approach to the Konkani language.

In the said chapter, Cabral also presents a modified alphabetic principle, in an attempt to rationalise the Roman script for Konkani; he highlights the differences between x/sh; i/y; d/dd; t/tt; n/nn and proposes the tilde as sole nasal marker, allowing m and n to be used exclusively as consonants. His makes a compelling case for well-defined orthographic rules, a step in the right direction.

In the penultimate chapter, on Ergativity, Cabral correlates Konkani with Latin and Sanskrit. He states that, there being no formal passive voice in Konkani, past and perfective tenses double up as seemingly passive in some tenses of transitive verbs. He indicates three ways to tell between transitive and intransitive verbs in Konkani. His catalogue of over 300 transitive and intransitive verbs, with their exceptions and meanings in English, is a ready reckoner.

At the end of a full course meal, the closing chapter, titled ‘Miscellaneous’, is a veritable dessert. It offers close to a hundred idiomatic expressions; several figures of speech; interesting proverbs; many puzzles and riddles (parkhonni/umanni); person and place names in Goa; and a handy glossary of a thousand Konkani words. Much as the book could do with tighter editing and better proofing, readers are sure to be charmed by its final chapter.

Ricardo Cabral, PhD, a teacher educator by profession, who retired from the Goa State Council of Educational Research and Training (SCERT) and has authored two books on education in Portuguese Goa, is deeply concerned about how Konkani in Goa has to reel under tremendous pressure from India’s two official languages: Hindi, given the large-scale immigration of its speakers; and English, given the Goan penchant for the language. He fears that soon there may be very few Goans speaking Konkani. Hence his effort – “to make the knowledge of Konkani available not only to those who want to learn the language but also to those who want to learn about the language, especially Goans in the diaspora” – is something that Goa ought to be grateful for.

KONKANI IN THE ROMAN SCRIPT, by Ricardo Cabral (Panjim: Qurate Books, 2023. Rs 735/-)

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 27, March-April 2024, pp. 63-65

https://online.fliphtml5.com/bcbho/agcy/#p=1

Paean to the Portuguese

THE PORTUGUESE PRESENCE IN INDIA, by João A. de Menezes. Chennai: Notion Press, 2020. Pp 346. ISBN HB 978-1-64850-628-4. Rs 1610/-

This is not macro-history like Danvers’ or Whiteway’s, but an account of the author’s life spent in the bosom of a third culture moulded by the Portuguese presence. In five autobiographical chapters interspersed with four others on broader historical issues he speaks his mind with a forthrightness not common in our days.

Three main strands stand out: the Goan way of life (“Goanism”), including emigration; the Catholic Church in Portuguese and British India; and Goa’s démarches in post-Independent India. “Goanism”, says the author, is anchored to the 451-year-old Portuguese stint and to the age-old comunidades that since the Vedic times have engendered powerful village loyalties.

The author’s own “loyalties” are evident. Despite the author’s long years in Poona, Aden, Bombay, and travels abroad, his heart beats for Goa. There are tender descriptions of ancient institutions; villages and households; the local church and cross feasts; markets and transport systems. Menezes is proud of icons like the Patriarca das Índias Orientais, the Cathedral See, the capital city Pangim, Radio Goa of yesteryear, the Taleigão harvest festival; and he gratefully remembers Governor-General Paulo Bénard Guedes, other men (priest granduncles Canon Bruno de Menezes and Fr Hipólito de Luna included), and matters that contributed towards shaping Goa (“with the exception of the Governor-General and the Chefe do Gabinete, all the other officials of the civil services were Goans and men of integrity”, p. 45).

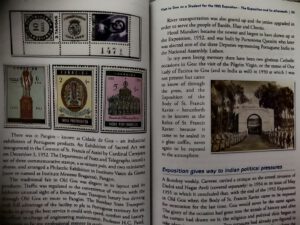

“Visit to Goa… for the 1952 Exposition” (of the Relics of St Francis Xavier) portrays Menezes as a young man, not only curious about the history of the former capital of the Portuguese Eastern Empire but also attentive to the political goings-on: the “problematic emergence” of the first Indian Cardinal, Valerian Gracias (and his sojourn at Panjim’s Hotel Imperial); pressures on Portuguese India; redistribution of Padroado territory in British India, and so on.

That visit hooked Menezes to his homeland. In “A Tryst with Goa”, he appreciates the cordiality from family and friends, set in a social ambience in which house doors “could remain open with no fear of intrusion” (p. 246). But “the happiest place on earth” (p. 274) was not destined to remain the same for long. The first satyagraha, which involved 100 (out of 100,000) Bombay Goans, in 1954, and none in the following year, demanding ‘liberation’ at the Goa border (p. 264); the severance of diplomatic ties between the Indian Union and Portugal; the Economic Blockade and terrorist threats, which made travel by land a nightmare, and the like, seem to account for the book’s subtitle, “Latter-day thorns amidst tranquillities”. Menezes participated in a first-of-its-kind pilgrimage to Old Goa, praying for peace, in 1956.

Menezes records Goa’s coming of age amidst those “thorns”, thanks to the induction of Transportes Aéreos da Índia Portuguesa (TAIP, whose airhostesses wore saris); upgradation of travel by land, sea, rail and air; optimising of farmland and other resources; importation of cars (Opel and Mercedes Benz as taxis, and the concept of shared taxis, p. 248) and other products; and boost to mining, with Chowgule & Co. as a concessionaire operating an iron loading facility while the rest of the port was managed by the British company that ran West of India Guaranteed Portuguese Railway (WIPR; p. 259).

In two chapters – “My Return to India from Goa” and “Travel between India and Portuguese India” – Menezes dwells on the run-up to the events of December 1961, viz. strategies to dismantle the Portuguese presence; the Goa Office at the Bombay Secretariat, among others. While the Brazilian Embassy’s service to Goans applying for Portuguese passports comes in for special praise here, the subject is dealt with extensively in “Brazil, Caretaker of Portugal’s Interests in the Indian Union – September 1, 1955 to December 31, 1974”. On the latter date, Portugal opened its Embassy in New Delhi.

Three chapters on lesser-known subjects – “The Portuguese Padroado or Patronage and the Indian State”; Indo-Portuguese Notes on Sovereignty”; and “The Referendum Rub: The Inflexibility of the Indian State to permit a Referendum” are mini-dissertations indeed. Menezes draws up a concise history of the Padroado (respected by the Peshwas) and of the Holy See-Portugal Concordat of 1940 (with text in English), and the implications for Goa. His unique contribution lies in examining the impact of Indian Independence on the Padroado, for which purpose he painstakingly translated and critiqued the India-Portugal correspondence contained in the four-volume White Paper titled Vinte Anos de Defesa do Estado Português da Índia (1947-1967), an invaluable resource for researchers.

To put together “Indo-Portuguese Notes on Sovereignty”, Menezes falls back on those diplomatic exchanges, declassified ahead of time (“an act without international precedent”) so the ageing Salazar could let the world know that he had defended the Portuguese Settlements in India with integrity (p. 131). Menezes calls the bluff of Goan political parties’ contribution to the fall of Dadrá and Nagar-Aveli (p. 171 ff) and ends the chapter with a note on “the conquest and subjugation of the Portuguese territories in India” (pp 182-3), with the text of the Indo-Portuguese Treaty of 31 December 1974 (p. 183 ff) added. The Appendix comprises a Goan, Bonifácio de Miranda’s address (apropos the Goa Case) at the UN General Assembly in 1969.

Finally, “The Referendum Rub” is the book’s pièce de resistance. Highlighting UN Charter’s principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, Menezes points to Chandernagore as the subcontinent’s only foreign settlement territory where a referendum was held to determine its political future. Although a referendum for Goa had votaries, “no such referendum was admissible or mandatory under the Estado Novo Constitution of Portugal” (p. 214). In Menezes’ opinion, even if it were permitted in Goa, “weighing the nuances, a referendum might have created more problems than it could solve” (p. 215). In hindsight, “Professor Aloysius Soares’ proposal of Portuguese autonomy [according] to a special constitution followed by a transfer to India with that constitution in place was a pragmatic approach to the future of the Portuguese territories…” (p. 219)

The Portuguese Presence in India, by João A. de Menezes, 90, who retired as chief mechanical engineer of Bombay Port Trust, is truly a labour of love, never mind the publisher’s price tag. A storehouse of memories and musings, blessed with period photographs and good get-up, the hardcover book printed on art paper could have done with better editing, bibliography and index. It is nonetheless a precious contribution to contemporary Indo-Portuguese history and a testament to the author’s love for Goa and insights into her soul.

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 25, Nov-Dec 2023, pp 44-46)

Fresh Legal Insight

Legal System in Goa, Vol. 1, Judicial Institutions (1510-1982), by Carmo Souza, [Self-published, 1995] pp. 189; Rs 150

Carmo Souza's book on the legal system in Goa is a welcome addition to the literature on a subject hitherto found only in Portuguese. Originally his doctoral thesis submitted to the University of Poona, it traces the developmental history of the judicial system in Goa from 1510 to 1982. This had been singled out for praise by the then chief justice of India, Mr Y. B. Chandrachud, when he inaugurated the Goa bench of the Bombay High Court at Panjim, in 1982.

Logically, the present work should have been preceded by a study on the legislation and legislative institutions of the corresponding period, in an independent volume. This is now expected to be out shortly.

The present volume assumes importance for several reasons. The Portuguese were the first colonial power to set foot and control a vast Oriental empire. Once Goa became their headquarters, the Tribunal da Relação, or High Court, was established in the old city of Goa in 1544. It administered justice at the appeal level to all the Portuguese settlements from the Cape of Good Hope to the China seas. With them was formed the modern concept of international law in trade, commerce, and navigation.

In the introductory chapter, the author refers to old and modern judicial institutions in Portugal and compares them with those set up in the Estado da Índia. Chapter 2 gives a brief idea of the pre-Portuguese judicial system in Goa, including the Comunidades, and goes on to discuss twenty major offices and institutions that administered justice sectionally, that is, "taking into consideration the different interests and pressures rising in the cosmopolitan society created by a maritime empire.” That list includes, among others, the Tribunal da Relação (treated in detail in chapter 3) and the Holy Tribunal of the Inquisition which, says the author, quoting a contemporary (ex-) Jesuit historian, had “apparently won the confidence of the natives.”

Chapter 4 dwells on the tumultuous period from 1800 to 1961, which saw the advent of constitutionalism in Portugal. A new process began with the decrees of 1832/36. Goan territory expanded with the addition of the New Conquests, where the indigenous system of judicial administration was allowed to continue, and uniform dispensation of justice came only towards the end of the nineteenth century.

"Post-Liberation Judiciary” makes up the final chapter. It treats the dismantling of a “vibrant system”. Problems encountered in the transition phase are brought out.

('Panorama', The Navhind Times, 1 Oct 1995. For longer version of the review, see 'Long Arm of the Law', in Herald - The Illustrated Review, 15-30 June 1995)

Love in Verse

VISIONS FROM GRYMES HILL, by António Gomes. Turn of River Press, 1994, 95 pp. Rs. 100

António Gomes, a eleven-year Goan veteran of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, is presently metamorphosed into a poet-philosopher. He examines the chemistry of suffering and joy, and attempts to decipher the mystery of life and death. After his wife died of cancer, in 1989, he thought he would never write poetry again. His inner world had been shattered by her departure. But God and Time are better healers than all our earthly physicians put together, and Gomes gradually came to terms with his loss and became whole again.

Visions from Grymes Hill is divided into two sections: “The Twilight Landscape” and “Poet’s Den”. In the first, the poems are more personal, reflecting his intense pain on the death of Marina. Gomes feels helpless that as a doctor he could not save her life. As he confesses in the Preface, “a doctor, a scientist and a heart specialist, I was engrossed in the miracles of Science. Yes, indeed! Science for me then was the one god I knew and understood above all gods. I was angry at this god for abandoning me. This god through whose intercession I had often mended the hearts of many men and women.”

Death laid its icy hands of her like an untimely frost upon the sweetest flower on all the field. The poet, unable to save her, is now in search of her. The poem “Visions” is a series of dreams reflecting this search, if not to find her – to find the answer. Born into a Roman Catholic family from Loutulim, Gomes now presents himself as an eclectic philosopher travelling through Hindu and Buddhist mythologies to find “the noble truth of the cessation of suffering” through “renunciation”.

The sad and humdrum life of a lonely man is reflected in the tone of some of the verse; but the sombre atmosphere turns to light whenever the poet chances upon the understanding of the mystery of life. Then he transcends his troubles and marvels at the myriad colours of human nature. His magnanimous heart looks upon the suffering of the “beggar and the hungry child”; his singing soul revels in music and dance as he draws the fine “portrait of a jazz pianist”, and Stan Getz.

Despite the magical confusion of his inner world, Gomes does spare a thought for Tiananmen Square and the Berlin Wall, communist dictatorships and Mikhail Gorbachev. All this is woven into his sensibility but he compulsively returns to “the image of my dear sick wife/Falling, rising, struggling/ Beautiful and hopeful to the very end”. Beautiful and hopeful, which is why even while a window closes on him with loss and sorrow another opens up with joy and hope. And as he turns his back on the images of the fateful year of 1989 “I welcome 1990, dancing with Tania, my only child”.

The “Poet’s Den” is an epic poem in which we follow the poet’s journey to disparate worlds and cultures. On seeking inspiration from the muse to write an epic, the poet is taken to a den where he encounters dead poets, ancient and modern. We are thus privileged to listen in on his intimate and far-reaching conversations with the great Bards from Dante, Goethe, Rilke, and Camões to Whitman, Tagore and Neruda.

The thematic range of this Section goes from the personal and religious to the social, economic and political. The issues reflect the events of the late 1980’s and early 90’s, “new challenges that have the immense potential of changing our world and our civilization”. Curiously, in these poems, written in the form of dialogues, Gomes blends his own poetry with that of the bards he encounters.

In Visions from Grymes Hill, which is his residence at Mount Sinai, António Gomes comes out as a man with the heart of a physician and the soul of a poet. Most touching is his line in the Preface: “I hope that those who read this book or parts of it will find these poets healing”. Witness the selflessness, the devotion, and the magnanimity of a fine doctor and sincere husband who invites us to partake of the pathos and passion of being fully human. The reader cannot help wishing that the poems have been cathartic for the writer himself.

(Herald -The Illustrated Review, 1-15 Sep 1995)

The long arm of the law

Legal System in Goa, Vol. 1, Judicial Institutions (1510-1982), by Carmo Souza, [Self-published, 1995], pp. 189, Rs 150

With the debate on the Uniform Civil Code picking up in the country, the history of the legal system in Goa can well be expected to come into focus very soon. Our Civil Code, framed by the Portuguese and still in force, as well as the judicial system developed by them, had been the object of praise for the then chief justice of India, Y. B. Chandrachud, when he opened the Goa bench of the Bombay High Court in Pangim, in 1982.

Carmo Souza's book on the legal system in Goa is a welcome addition to literature on the subject hitherto found only in Portuguese. Originally his doctoral thesis submitted at the University of Poona, this academic presentation traces the developmental history of the judicial system in Goa from 1510 to 1982. Logically, this should have been preceded by a study of the legislation and legislative institutions of the corresponding period, in an independent volume. But this will hopefully come as a sequel.

The present volume assumes importance for several reasons. The Portuguese were the first colonial power to set foot and control a vast Oriental empire. Once Goa became their headquarters of the empire, the Tribunal da Relação, or High Court, established in the old city of Goa in 1544, administered justice at the appeal level to all the Portuguese possessions and settlements from the Cape of Good Hope to the China Seas. With them was formed the modern concept of international law in trade, commerce, and navigation.

In the introductory chapter, the author refers to old and modern judicial institutions in Portugal and compares them with those set up in the Estado da Índia. Chapter 2 gives a brief idea of the pre-Portuguese judicial system in Goa, including the Comunidades, and goes on to discuss twenty major offices and institutions that administered justice sectionally, "taking into consideration the different interests and pressures arising in the cosmopolitan society created by a maritime empire.” That list includes, among others, the Tribunal da Relação (treated in detail in chapter 3) and the Holy Tribunal of the Inquisition which, the author says, quoting a contemporary (ex-) Jesuit historian, had “apparently won the confidence of the natives.”

Chapter 4 dwells on the tumultuous period from 1800 to 1961, marked as it was by the advent of constitutionalism in Portugal. A new process began with the decree of 1832/36. Goa saw the addition of the New Conquests, wherein the indigenous system of judicial administration continued. Uniform dispensation of justice came only towards the end of the nineteenth century.

"Post-Liberation Judiciary” makes up the final chapter. This treats the dismantling of "a vibrant system”. Problems encountered in the transition phase are brought out. Interviews with judges and lawyers of the erstwhile regime, if included here, might have thrown more light on the topic.

Souza attempts to provide insight into whether certain institutions under the civil law system may be used in the Anglo-Indian system and the possibility of creating healthy hybrid institutions. He mentions the possibility of Goa having a High Court of its own.

Legal system in Goa is not critical as to advance any value judgements. This does not, however, detract from the rich documental value and the pioneering effort at systematization undertaken by Carmo Souza of a much neglected body of knowledge. His work could well serve as a background for the studies of judicial institutions of erstwhile Portuguese colonies in Asia, Africa and South America too.

(Herald - The Illustrated Review, 15-30 June 1995. A shorter version of this review, titled 'Fresh Legal Insight', appeared in 'Panorama', The Navhind Times, 1 Oct 1995)

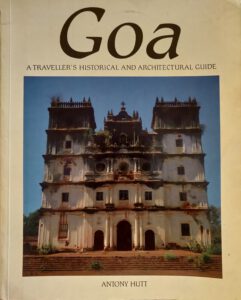

Mapping Goa's Architecture

Goa - A Traveller's Historical and Architectural Guide, by Antony Hutt. Scorpion Publishing Ltd, England. Rs 200

It could well be called a serious work written for the casual traveller. More specific academic exercises have preceded this one since the 1950s but the highlight of Antony Hutt's book is his comprehensive treatment of Hindu, Christian and Muslim architecture – civil, religious and military.

Out of the nine chapters the first five are devoted to the history of Goa – right from the early times down through the Hindu and the hitherto neglected Muslim period, up to the Portuguese connection, when Goa got to partake directly of the history of the modern world. However, the 20th century is almost entirely left out.

The historical account is highly readable, largely chronological, though desultory at times. Refreshing it is to find the history of tiny Goa placed in the larger context of the history of India and the world. Hutt is well disposed towards the Portuguese, the Inquisition notwithstanding, and is of the opinion that they "inaugurated the most brilliant period in her history".

Old Goa alone becomes the subject of chapter 6. The Indian Baroque church of the Holy Spirit (St Francis of Assisi), the church of Our Lady of the Rosary, St Catherine, the Cathedral See, Grace Church (St Augustine's), the Royal Chapel (St Anthony), St Monica Nunnery, the convent of St John of God, the Minor Basilica of Good Jesus, St Cajetan, church of Our Lady of the Mount, the Viceroys Arch, and the Archaeological Museum – twelve monuments, all of them mapped. Good treatment this but no real revelations whatsoever.

The next few pages are devoted to Portuguese architecture outside the capital city. This is followed by a novel chapter on the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture.

It is in the following chapter that the author is least original in what concerns civil and religious architecture. Salcete, and more in particular, Loutulim, forms the main thrust, and what follows is a routine description of only the better known houses in Salcete – the da Silva mansion in Margão, the Miranda and Figueiredo houses in Loutulim and the Menezes Bragança in Chandor, the only exceptions this time being the Salvador Costa house in Loutulim and perhaps also the Souza Gonçalves and Albuquerque mansions in Bardez.

On the other hand, a novelty is certainly the description of the forts of Goa: Tiracol, Chapora, Aguada, Reis Magos, Gaspar Dias, Cabo, Marmagoa, Cabo de Rama and the inland fort of Santo Estevam, all find their rightful place in Hutt's book.

In contrast with the earlier chapter, what constitutes a real contribution is Hutt's elaboration of the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture. It is, however, most unfortunate that there is not a single picture of any of the six Hindu houses described – the Sinai Kundaikars in Kundai, the Ranes in Sanquelim, the Khandeparkar house in Khandepar, the Dempo and Mhamai Kamat houses in Panjim and the Deshprabhu palace in Pernem. We are only left to imagine what they really look like.

More than nine temples are included, the earliest being the rock-cut sanctuaries of the 3rd-6th centuries A.D., most of which are Buddhist in origin; Sri Mahadeva temple, Tambdi-Surla; Shiva temple (Curdi), Saptakoteshwar (Naroa); Mahalsa, Mangueshi, Shantadurga; Kamakshi (Siroda), and Mahalaxmi (Bandora). There are specific references to the "odyssey" of many Hindu deities of Goa.

Hutt was in love with Goa and visited it often from the 1970s to the 80s. He could not then possibly miss out a comment on the life of the Goan people. And the final chapter is just that, a paen to the Goan genius: the warmth and colour of the people, the traditional communal harmony, and so on. But this sociological exercise should have been accompanied by a more definite statement on the nature of popular architecture in Goa – a point that is sacrificed at the altar of elite architecture, so to say.

A good bibliography can serve as a delicious dessert for the curious mind. Sad to say, here the book is a complete let-down. The scanty information cannot satisfy even the least curious of travellers/readers. There is not even a minor reference to the works of Mário Tavares Chicó or Carlos de Azevedo from Portugal nor to the historical works of Danvers, Gabriel de Saldanha or José Nicolau da Fonseca. Rather mysterious references are made to books published after the author's death, and for that matter, other books figure in the bibliography from which not a line or illustration is traceable in the text. Also missing is a detailed map of Goa.

All in all, an impressive book. Good get-up, fine printing. For certain shortcomings of the text, every reader would be willing to make certain concessions given the author's premature death in 1985.

(Goa Today, November 1989)