Holy Passion Processions in Panjim

At the Church of the Immaculate Conception – the Igreja Matriz or main parish church of Panjim – the sixth Sunday of Lent begins on a festive note. It is Palm Sunday, which commemorates the triumphant entry of Jesus in Jerusalem.

However, after the morning Masses, there is a visible change in the mood, especially with the unveiling of the tableau in the chancel: a larger-than life-size statue of Christ carrying the Cross. Hence, the day's alternative designation: Passion Sunday.

The evening of Passion Sunday features a solemn procession that begins from and ends at the iconic church. It is the highpoint of the Santos Passos (‘Holy Steps’) held on the first five Sundays of Lent, highlighting some of the most intense moments of Christ’s Passion leading to Calvary: the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane; the Arrest of Jesus; the Flagellation at the Pillar; the Crowning with Thorns; the condemnation by Pontius Pilate (See my blogpost https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2019/03/17/santos-passos-in-panjim/ ). Other churches in Goa do not necessarily have the same set-ups (See https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2021/03/21/lenten-traditions-in-goa/ ).

Passion Sunday signals the beginning of the Holy Week. The predominant colour is purple; the altars are bare and there is not a flower arrangement to be seen. After the evening Mass, a procession called Cruz às costas – the same tableau of Jesus carrying the Cross – wends its way through some of the main thoroughfares of the capital city: the Church square, a section of 18 June, Pissurlencar, past Azad Maidan.

Confrades (Church confraternity members) wearing opa e murça (a red and white cape) carry the statue concertedly, giving the impression that it is floating on its own power. In the past, a brass band would follow; but nowadays, a choir sings from an intermediate landing of the church's zigzag stairway. The singing and prayers are heard throughout the route via funnel loudspeakers. The procession is animated by the recitation of five Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary until the end of the procession.

The circuit is marked by over ten descansos (halts), at which points the faithful flock to kiss the statue. A major halt happens at the Capela da Conceição (Chapel of the Immaculate Conception). Built in 1823, it was once a private chapel attached to the mansion of Dom Lourenço de Noronha, scion of a Portuguese noble family, and was later bequeathed to the Confrarias of Panjim church and has been under repairs since 2019.

The cavalcade then proceeds via M. G. Road and Dr D. R. de Sousa, past the Garcia de Orta Garden, and up to the church square. Here, at the foot of the stairway, Jesus is met by His Blessed Mother. Sorrowing over her Son so unjustly accused and made to carry the Cross to His death, she accompanies him on his last last legs, as she did two thousand years ago to Golgotha.

Soon thereafter, the two statues halt on the intermediate landing in front of a large cross carved out of the wall. A level higher, from a pulpit-like balcony jutting out of the said wall, a little girl unrolls the Veil of Veronica while she sings the traditional narrative. This is about the meeting of the legendary woman (feast day, 12 July) with Jesus. As recorded in the fourth station of the Via Crucis (Way of the Cross), Veronica, moved by the sight of Jesus carrying the Cross, wiped his brow with her handkerchief only to find a lasting imprint of his holy face on the cloth.

Thus ends Passion Sunday and preparations begin for the Holy Triduum beginning on the evening of Maundy Thursday. This day, which comprises a Mass with the reenactment of the historic Washing of the Feet by Jesus, marks the institution of the Eucharist and the Priesthood and the proclamation of the Commandment of Love. There is no public procession.

Five days later, on Good Friday, the processional arrangement is the same as on Passion Sunday, except for a few obvious differences.

The poignant Crucifixion tableau opens in the chancel at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. It is interesting how by then the sky is usually cloudy and the mood sombre. The liturgy of the Word and the Eucharist continue until at about half past five. Then, a procession of a larger-than-life-size statue of Senhor Morto (The Departed Lord) placed on an andor (black canopied wooden platform) starts off, with the statue of Our Lady in trail.

There are some other differences too. Today, the faithful are in funereal attire, which once upon a time was de rigueur. And instead of the sanctus bell, we hear the matraca or wooden rattle at every halt in the procession.

A major difference between the Passion Sunday and the Good Friday procession lies at their very end. This time round, in a coda to the baroque event, is the Sermão da Soledade de Maria (Sermon on the Solitude of Mary) delivered by a priest from the same pulpit-like balcony. The preacher extols the virtues of Mary and highlights her present solitude. Formerly, rhetoric played a crucial role on such occasions, helping to fully engage the congregation. Nowadays, the limited number of faithful who stay on to listen are easily distracted, not least by vehicle noises that detract from the solemn ambience.

In this context, one striking similarity between the processions is that both are watched in awe by people of other religions. On both occasions, residences put up decorative lights, candles or oil lamps in homage to Our Lord. Some non-Christian establishments remain open, it being a weekday, do the same. People from other religions watch in awe, including policemen (one of whom I saw standing at attention and saluting the Departed Lord). Particularly interesting is the case of the Caculos and the Neurencars, two Hindu families on Pissurlencar Street; they traditionally offer garlands of xenvtim or abolim.

Depending on the number of attendees, the pious, kilometre-long march and related ceremonies on both days take between 75 and 90 minutes. The statues return to the church for concluding rites and veneration. By 8 o’clock, they call it a night!

Behold two processional events in Panjim that have left a lasting imprint on my mind. So was it when my life began; so is it now I am a man. So be it when I grow old – for this ancient tradition is without a doubt one of the most moving spectacles in the religious and cultural calendar of my city, Panjim.

Requests:

1- In the comments section below, do share snippets of similar traditions in your village or city, and document them whenever possible.

2 - Do watch my video titled "Passion Sunday Procession in Panjim", on http://www.youtube.com/@oscardenoronha

Mary to Mira: just a sound away?

The article titled ‘Milagris and Lairai: fostering the bond of divine unity’, by historian Dr Sushila Sawant Mendes (Herald, 23 April 2023)[1] has added to the myth rather than clarified it. One would expect to be enlightened on the origin of the statue of Our Lady of Miracles (also Milagr Saibinn, in Konkani), or the story of the Seven Sisters, or even be favoured with a sociological or anthropological explanation; but that was not to be. At any rate, as a lay reader, I wish to raise a few issues about its interface with Catholic practices in Goan society.

To start with, the loose use of the term ‘divine’ with reference to Our Lady leads to considerable confusion. Mary, the mother of Jesus, is not a goddess but a human being, whereas Lairai, shrouded in legend, is one of the seven sister goddesses to the Hindus. Why link a historical personage to a mythological septet? It is therefore gratuitous to put Lairai on a par with Milagr Saibinn.

Quite understandably, the article is riddled with expressions like ‘It is believed’ and ‘Legend has it’. But saying that “Milagris Saibin is believed to be the deity Mirabai, a sister of Goddess Lairai” begs the question: believed by whom? Is there a formal acceptance of the belief, or is it a belief held by an amorphous mass of individuals that offer flowers or pour oil on the statue? The latter practice is, perhaps, of recent origin and the only one of its kind in Goa.

From the Catholic perspective, the story is not Mariological. And stating that “There is a tradition to offer oil to the Milagris Saibin from the Shirigao Devasthan and mogra flowers are offered to Lairai Devi from the St Jerome Church in Mapusa” is not in keeping with any official Catholic tradition in Goa. So, the onus of showing the origin of such a protocol, if any, lies on our historian-writer.

That the purported institutional exchange is a no-no even from the Hindu side was confirmed by iconographer Dr Rohit R. Phalgaonkar, who has researched the issue.[2] No doubt, Mirabai was one of the seven sisters from folklore, but after her abode, Mapusa (not Mayem, as stated in the article), converted to the Catholic faith, way back in the sixteenth century, the temple authorities in Shirigao (and elsewhere) stopped mentioning Mirabai in the traditional invocations. In fact, “none of the sister temples make a reference to Milagris in their official records and in the religious duties or rituals that they perform at the festival. She is not an icon of the Hindus; she is a Christian icon," he added.[3]

Therefore, to say that Milagr Saibinn has taken the place of Mirabai is not plausible; and Dr Phalgaonkar wonders why Milagr Saibinn would have a link with Lairai alone and not with the other sisters! This only goes to prove that, if the issue is not handled with academic rigour, it can be grist to the myth-making mill even in our day and age.

Not surprisingly, there is a dash of magic realism, which helps bring the story alive: “… it is believed that the two sisters visited each other on the day of their respective festivals.” And risking repetition, the writer says, “Folklore tells us that Milagris Saibin would send flowers as a gift to her sister, Goddess Lairai, during the zatra. Lairai would send in turn oil for her sister’s feast.” That is to say, while earlier on in the article, the two institutions were given credit for the magical feat, now it is Milagr Saibinn and Lairai Devi themselves who show how they care for each other! Can scientific writing sacrifice accuracy at the altar of artistic licence?

With the theme of unity and a sense of disclosure ever present, the writer is keen to show that Goa is an oasis of intercommunal peace; and she bends over backwards to prove her point. That “every generation of the people of Assolna, Velim and Cuncolim have grown up with the belief that the Goddess Shantadurga of Fatorpa is the sister of Saude Saibin of the Church of Our Lady of Health in Cuncolim” is either an exaggeration or it speaks poorly of the catechesis received by the Catholics of those villages (AVC).

That is a facile generalisation, which, read alongside the sentences now in parentheses (“The festival of the Sontrios in Cuncolim and the devotional visits of the Catholics to this temple is a graphic representation of this undying belief. Tomorrow is both the feast of Milagres Saibin at Mapusa and the Shree Devi Lairai Zatra at Shirigao, both to be celebrated on the same day after thirteen years, on April 24 this year”) summarily puts Catholics across the length and breadth of Goa under the sontri or umbrella of a syncretic religion.

The article runs high on emotions. After referring to Lairai’s many sisters, the writer states: “Since all are still sisters, it is understood that people worship at either their temples or churches. It is an emotional explanation of how Goans are still one people with one culture even if, on the surface, they are divided.” Is the writer implying that Goans randomly visit places of worship – and does that effectively prove that they are “still one people with one culture”?

It is undeniable that the Indian Constitution allows freedom of religion and worship, but does that lead to licence? We get the impression that Goan Catholics and Hindus have no sense of belongingness and loyalty: they run with the hare and hunt with the hounds. Especially Catholics, followers of a monotheistic religion, to insinuate that they worship indiscriminately is a slur on their character.

We are catapulted into the next stage of mythification, on reading the story of Lairai fighting with her brother Khetko. When the writer says that “The ceremonies [at Shirigao] culminate when devotees walk through fire as acts of repentance by the two sisters who had mistreated their brother”, it is not clear which sister fought alongside Lairai and has been paying for it till date. Contextually, or say, in the writer’s variant of the myth, would it be a reference to Mary who has supposedly replaced Mirabai? The fact of the matter is that Mary had no brother and her world was one of meekness and peace.

Is it only a step from Mary to Mira? Or so it is made to appear – just a transposition of syllables! Whether or not “Goans worshipped the Mother Goddess in a number of forms even before the Portuguese arrived”, it is improper to say that “with the coming of the Portuguese, the Virgin Mary was introduced in her various versions”, for the Blessed Virgin Mary has no “versions” but only invocations and titles. Add to it the statement that the “Goans thus turned from one form of Mother Goddess to worship another”, and you have a gross oversimplification of the historical situation! And needless to say, to examine the claim that “many temples dedicated to the Mother Goddess were rebuilt as churches dedicated to Our Lady” would require a thorough historical approach.

To conclude: Considering that no society is devoid of myths, or even completely homogeneous in its myths, we can make allowances for the article’s ‘mythical reasoning’. India is a land abounding in myths and legends; we usually take them in our stride, considering that they have come down from a remote past over which we have no control.

Accordingly, living as we do in a secular democracy striving towards peaceful coexistence, the writer has ended up secularising the myth, of course, cherishing a well-founded hope for “a strong bond of unity”. But whereas this unity is desirable and even achievable at the social level, to endeavour to merge institutional identities, unite heterogeneous beliefs, and mix up religious doctrines is unacceptable.

Can we guard against processes leading to new myths? It is the bounden duty of academics to get to the bottom of it lest peace and unity become a myth.

Banner: https://gogoanow.com/milagres-feast-celebrated-st-jeromes-church/

[2] Cf. his lecture titled ‘Seven Sister Goddesses’ at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BDsQFx4jpII

[3] Interview with Dr Rohit R. Phalgaonkar, 28/29.4.2023.

The Goan Football Story

Apropos the forthcoming FIFA World Cup 2022, here are excerpts of a chat by José António Botelho, Jovito Lopes, Eddie Noronha and Sávio de Noronha with Óscar de Noronha, on the radio programme Renascença Goa.

ON: The World Cup is also an occasion for us to talk about football in Goa….

JL: Originally, football was brought to Goa by Father Robert Lyons, who had a school in Arporá, in the taluka (concelho) of Bardez. In Pangim, it is said that the Salesians of Don Bosco were the pioneers: Father Scuderi rode around the city on a bicycle and attracted the boys from the street. Also, the churches in Goa have fields where young people play. Therefore, football was an attraction for the youth.

In front of my house, in Fontainhas, it was a mud street. Nonetheless, we played football in the street. From 5 to 7 in the evening, we would get together and play with a ball made of socks. We didn't have the footballs we have today. We would also go and watch football played on the Police Grounds… Académica, Sporting, and other teams. As children, we didn't have any money, and we couldn't enter the stadium without a ticket. So, when someone we knew went there, we would enter in the shadow of these friends, let's say, on the sly…. Football was indeed a sensation. As kids, it was sensational to see someone play well, score goals, etc. And we had great players, like Alcântara, and others. It was a sensation.

ON: What was your involvement with football?

JAB: When I was a student at the Lyceum, some friends of mine played for Sporting Clube, which was based at Lar de Estudantes; and we were fans of Académica, so much so that later, in 1974, when I had my own team, Panvel, it was really a reincarnation of Académica…. We changed the name and played as Panvel, but at heart we were still Académica…. we even played wearing black shirts. It was football from the heart; it was more emotion and less training. Sometimes we didn't even have enough uniforms…. Earlier, the rule was that only one player could be substituted before half-time, and sometimes there was not even an extra shirt for the substitute. The substitute wore the same sweaty uniform of the player who had just left the field. It was more exciting from the player’s and manager’s point of view, but maybe not so much from the point of view of the show and the spectator...

ON: Undoubtedly, football has changed a lot over time…

JAB: Yes. In those days, if we won a match, we would at the most get bhaji puri and tea; but now it's quite different: you get paid a lot of money! In 1966, we followed the World Cup in England, listening to the radio reports. We got to see the finals, almost 6 months later, at Jardim Garcia de Orta, when someone brought a projector with the black and white film. Today, of course, you get to see the game in real time….

ON: Of course, things have changed a lot with technology, that is, with television; but in the days of the radio and newspapers, did the people here follow the happenings closely?

JL: Radio has made a big difference in Goa. When there were these Goan league games, they were held simultaneously in Vasco da Gama, Margão and Pangim. There were radio reports of all three games at the same time: which doesn't happen now. In those times they were the Ferroviários or independents, and there were many Portuguese playing; and the Académica too. And all the games were on the radio, and we already knew who was playing for which team; who won, who lost, from day to day… something that doesn't happen nowadays...

ON: What is the reason for this?

JL: That’s because there are games on television. People are more interested in English leagues than in the Indian leagues…

ON: Who are the big names of Goan football?

JAB: The first coach I remember is Cirilo Ferrão, who built Shantilal's team. Then Shanmugam, from Bangalore, and he was here as coach of Salgãocar. Among the Goan coaches, in addition to João Leite Melo, who was a player for Académica, and was also coach of my team, Panvel, and of Sesa Goa, Salgãocar, and, lately, I think he was coach of Cidade de Goa, which was a team of the present Sporting Clube de Goa. Among the players, Dominic Soares, that forward line of Vasco – ABCD – Andrew, Bernardo, Catão and Dominic Soares – and later, Arwin da Silva, goalkeeper, Jorge Abranches, Vasco, and others – although these are not Goans. But the four people I mentioned first were Goans, although Catão had made a career in Bombay before coming to Goa, Bernardo had been in Vishakapatnam before returning to Goa, and Tanzanian-born Dominic returned to Goa as his parents were from Goa. These were the good players I remember. Then, the other generation that mostly passed through Panvel were Brahmanand Sancoalcar, Rosário Rodrigues, Derek Pereira, Maurice Afonso, Silveira, Bruno Coutinho…. I don't know if we're going to have such players now.

ON: What would you say of the present generation?

SN: After the generation of Bruno Coutinho and Roy Barreto, who had a good combination and won many tournaments as players for the State of Goa and its clubs, in the next generation came Romeo Fernandes, Kelvin Lobo, Mandar Rao, Sahil Távora…. This generation had the opportunity not only to play football at a very high level in the gaming business in India, but they also started to earn a lot of money compared to the footballers of the previous generation, thanks to the Indian Super League (ISL), and this gave many young people the opportunity to make a football career.

ON: Who were the promoters of football in Goa?

JL: Lubé Távora had a team from Siolim, which was called “Kitem Fine”! Then, Académica was the student team. Everyone wanted to have that black shirt…. What a passion that was! And at the time, there were no other games. There was no cricket, there was nothing; It was just football, football, football.

JAB: People like Dr Alvaro Remígio Pinto; Bento Fernandes; Hermano Fernandes, from Santa Inez, they were all dedicated to the club cause; even Dr. Pinto, who together with Aranha, founded Académica; Father Chico was from Sporting and also from Lar de Estudantes, whose players he trained. He had a gift for talking to his men. Nowadays it's easier because we have managers trained to do that. So, a priest knowing how to do that then was rare and very important.

ON: Fortunately, today there are clubs, like Sporting Clube de Goa, that train young people!

EN: Our main objective is to promote young Goans. We have a senior team that is professional and one of the main clubs in the country. We also have a youth development programme, for teams under 20, under 18, under 16, under 14, and under 13. The team participates in championships organized by the Indian Federation and the Goa Football Association. We have an academy for children at the Don Bosco school in Pangim with which we have an agreement. In addition, we have adopted some schools – which means that we support them, providing technical staff and equipment…

ON: The Indian soccer leagues have aroused a lot of interest. What do you think of this?

EN: We are the only country in the world with two leagues, the I-League and the ISL. With the introduction of ISL, technically, each ISL team is allowed to have more than two foreign players. With this, the inclusion of Goan and Indian players in the team is restricted. In the Indian league only four foreign players can play, giving more opportunities for Indian players to participate. Due to this conflict, three Goan clubs – Sporting Clube de Goa, Dempo Sports Club and Salgãocar Sports Club – withdrew from the I-League some years ago. We hope that the All-India Football Federation will review the decision to have a single championship and that all Goan clubs get into the top division on merit…

JAB: Football control is in the hands of people who don't know anything about football, or don't know professional football. That's not going to change anytime soon. That's where the idea of ISL came from. The mistake was to let the I-League and the ISL continue. They should have done what Japan did: stop all football that existed and start again….

ON: Are Goans readily accepted at the national level?

JL: Only in the last few years there has been a problem. It is said that relations between the Goa Football Association and the Federation are not in good shape. But, by the way, the Indian team always had four players from Goa, which is not the case now, for several reasons…

ON: What is the experience of the Lusofonia Games?

SN: One of the best moments for football in Goa was when the Indian team, with the majority of footballers of Goan origin, won the gold medal at the Lusophone Games, in 2014, when they were held in Goa…

ON: What do you think of the future of football in Goa?

SN: As for the future of football in India, and in Goa in particular, I think that the official organizers of the game in the State of Goa have to reach a consensus with the national federation and clarify what doubts they have against each other. At the moment, things are not going very well but I think the game has to be given the highest priority if it has to improve…

JL: There needs to be a revolution in our thinking. The approach must be totally professional: they must let professionals and technicians execute their vision.

Other participants in the original chat in Portuguese, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uyJh4smJV2M : Julio Fernandes, Yolanda de Sousa, and Vera de Noronha.

(First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, https://casadegoa.org/revista/ii-serie-n-o-19-novembro-dezembro-de-2022/

Series II, No. 19, November-December 2022)

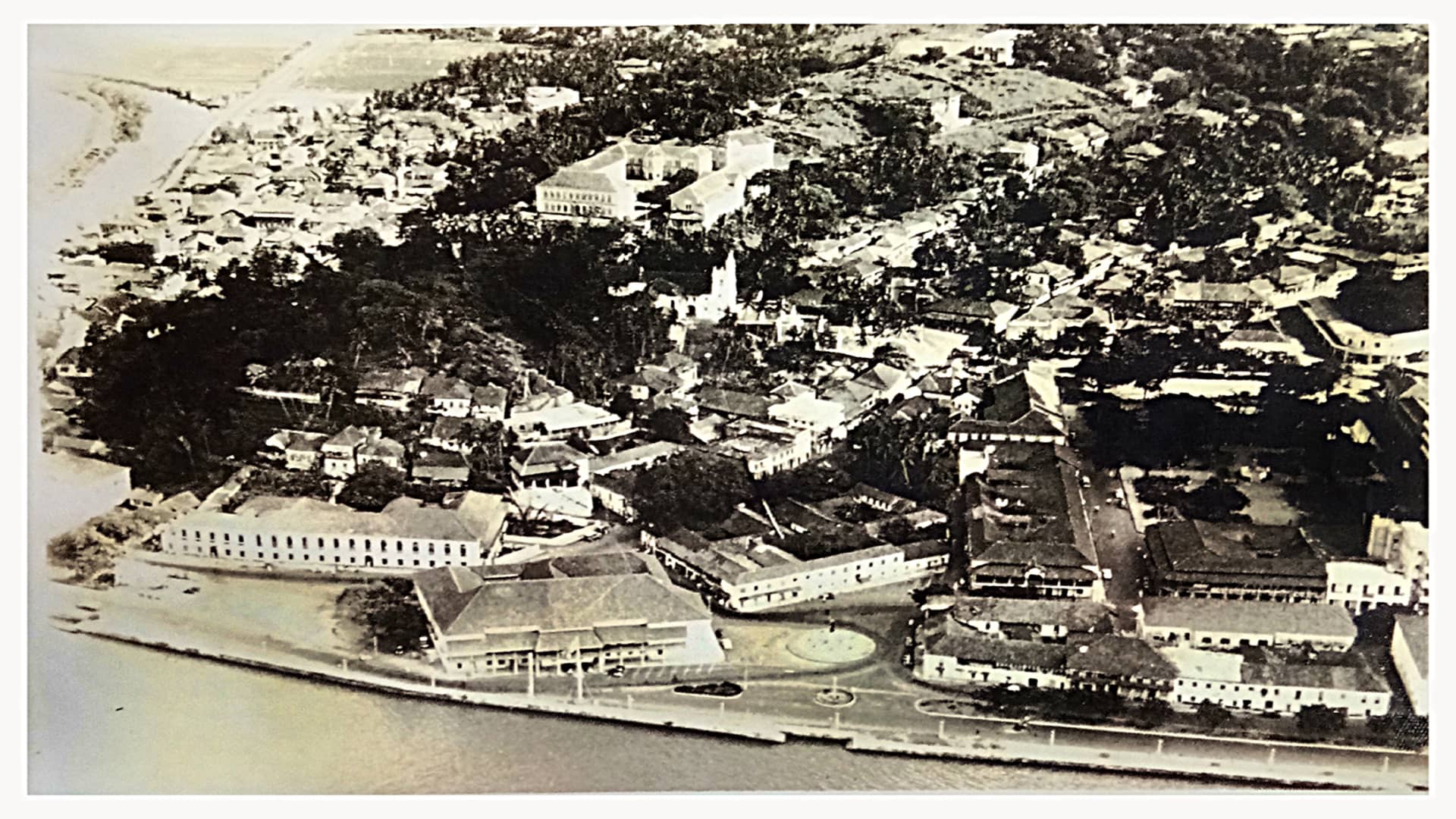

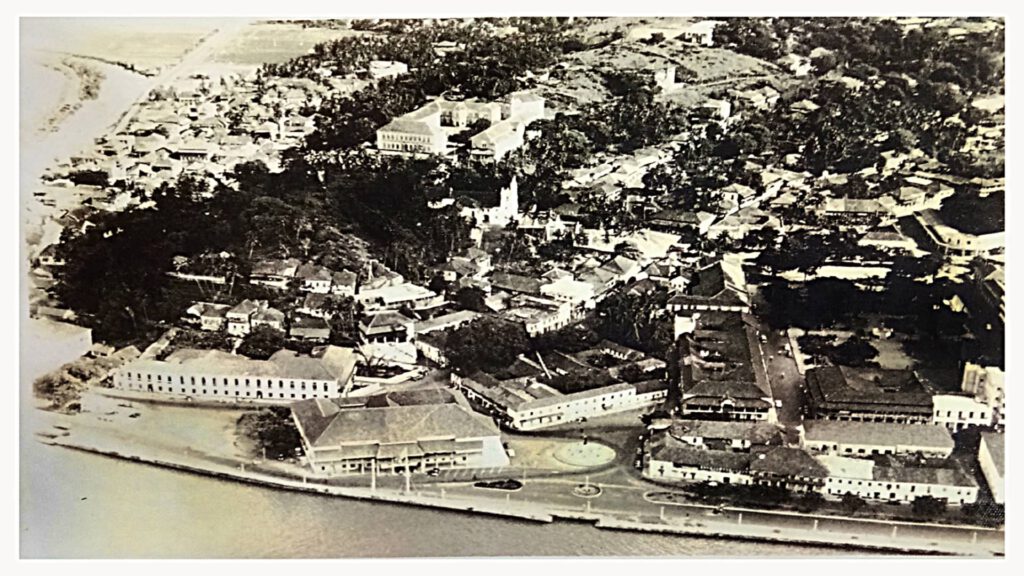

Pangim da minha infância

Nas décadas de 60 e 70 do século XX, a cidade de Pangim era a imagem da calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro. Estendia-se da Rua de Ourém ao Hospital Militar (na direcção leste-oeste) e da avenida marginal ao Altinho e Batulém (na linha norte-sul). Como jardim à beira-mar plantado, a quem o suave Mandovi pautava o ritmo da vida, Pangim tinha uma identidade própria e um encanto muito seu.

Vivia eu no coração de Pangim, ao pé do antigo Palácio do Idalcão e sob o olhar hipnótico do Abade Faria. Raiava o nosso dia com o chilrear dos pássaros, seguido da sonora sereia do barco de Bombaim a atracar no cais da Alfândega. A essa hora, o vaivém apressado da multidão, a algazarra dos bagageiros e a buzina dos táxis na Avenida Vasco da Gama (hoje D. B. Marg) eram um chamariz para uma boa parte dos 40.000 pangimnenses ainda envoltos em sono; um impulso matinal para as suas tarefas, sobretudo a escolar.

Era como se o frenesi da metrópole indiana tivesse acabado de desembarcar na capital goesa! Essa onda pressurosa propagava-se um pouco por toda a parte, a começar pela Avenida Dom João de Castro e a Rua Afonso de Albuquerque (ora M. G. Road), as principais artérias, dominadas pela burocracia e pelo comércio. Com a partida daquele barco, no meio da manhã, a cidade voltava à calmaria; almoçava e dormia a sesta, e pelas 4,00 horas retomava a batalha quotidiana que só terminava por volta das 8,00 da noite.

Uma vivência orgânica, não muito diferente da do campo! À devida hora vinha à porta o pão e o peixe fresco; iam às compras os empregados domésticos, que se prezavam de ser íntegros, temendo não tanto a polícia como a Deus! O trânsito era ligeiro – motocicletas, bicicletas, até carroças, e automóveis, do popular Volkswagen ao luxuoso Cadillac. Estes eram os últimos abencerragens da bonança que resultara, paradoxalmente, do Bloqueio Económico de 1955, e ora simbolizavam o nosso cosmopolitismo.

Disse um escritor japonês que Pangim era a “most unIndian of all Indian cities.” Referia-se certamente à tradicional arquitectura indo-portuguesa, desprovida de arranha-céus e da imundície e do caos que caracterizavam os centros urbanos do subcontinente. Mas teria ele dado conta da arquitectura espiritual do povo? Este não era de grandes ambições e vivia numa mediania. O roubo era raro, e raríssimo o homicídio ou o suicídio. Não havia indícios de sectarismo ou de violência, pois reinava a consciência e a benevolência, ou aquilo a que chamamos munisponn: se à porta humildemente batesse alguém, sentava-se à mesa com a gente – como canta o fado; e no conforto pobrezinho do lar havia fartura de carinho, e bastava pouco para alegrar a existência do citadino.

Pois é, a cidadezinha daquela época tinha um só diário em português (O Heraldo) e em inglês (The Navhind Times); uma só emissora (a All India Radio); um só salão (o do Instituto Menezes Bragança), onde actuava a única academia de música; um único hotel de categoria (o histórico Mandovi); uma só loja de gelados (o Esquimó); um só restaurante sul-indiano (o Shanbhag); um único hospital geral (o da Escola Médica); um único cine-teatro (o Nacional); uma só livraria (a Singbal); uma única biblioteca de fôlego (a Central); uma só grande praça pública (o Azad Maidan); um só campo de jogos público (no Campal); um só amplo jardim (o Garcia de Orta), onde, à tarde, convergiam crianças e adultos, ficando aqueles a saltitar pelos canteiros e estes a conversar amenamente num canto.

Desse jardim guardo várias memórias: a da música executada no seu artístico coreto e a dos slogans – “Tujem mot konnank? – Don panank!” – que eu ingenuamente gritava, nas vésperas do Opinion Poll, em 1967. Lembro-me dos cafés e bares em redor e do jornal em cuja Redacção se ouvia um aflitivo dize-tu-direi-eu, nem por isso resolvendo os problemas da carestia e escassez, da pobreza e embriaguez, estas comuns, por sinal, no bairro pitorescamente denominado Tambddi Mati (Terra Vermelha), tanto por falta de asfalto nas ruelas como pelas lampadazinhas vermelhas nos alpendres!

Enfim, Pangim não era nenhum jardim de virtudes. Até pensara em mudar de cidade, por não suportar a insularidade e me sentir everybody’s business; mas em vez disso mudei de ideia, por recear que entretanto a cidade da minha infância se transformasse num pequeno Bombaim, e nós, em nobody’s business! Mas não havia remédio; a cidade estava já em franca expansão: as casas cediam o lugar a blocos de apartamentos; era construída uma ponte sobre o Mandovi e uma praça de automóveis no pântano do Pattó. Por outro lado, estava incompleta a rede de esgotos; havia falhas na electricidade, e era racionada a água canalizada. O ar era puro; mas ai que, na monção, Pangim de repente era Veneza!...

Ora, fui aprendendo a amar a cidade e a gente. Éramos poucos, éramos irmãos – e saudáveis as relações entre os vizinhos, independentemente dos seus credos. Naqueles tempos, os cavalheiros tiravam o chapéu às senhoras e paravam para dois dedos de conversa! Os baptizados, aniversários e funerais eram eventos de vulto. Não havia televisão; para dissolver o tédio bastava um passeio pela praia do Miramar ou de goddia-gaddi até ao Campal, ao pôr-do-sol. O arraial nas Fontaínhas, o desfile do Carnaval e os bailes nos clubes Nacional e Vasco da Gama vinham a seu tempo. Dir-se-ia o mesmo da Via Sacra; da procissão das velas que do Paço Patriarcal descia até ao ex-libris da igreja matriz; e das novenas e festas religiosas. De tudo isso nascia o espírito de família e a alegria de viver em Pangim.

No afrouxar forçado dos meses da covid-19, voltei a descobrir o rosto da minha cidade. Se em tempos nos faltavam coisas que os outros tinham em abundância, hoje, sentindo novamente aquela calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro, vejo que nos não faltara nada…. Não admira, pois, que Pangim tivesse sido sempre a menina dos olhos de todos os que se prezavam de ser goeses!

Foto de Pangim, gentilmente cedida por Willy Goes

Publicado na secção portuguesa do magazine dominical do diário Herald

As realidades da nossa identidade

As minhas primeiras palavras são de agradecimento pelo honroso convite que me foi feito de integrar o conselho editorial desta dinâmica Revista, e de saudações aos leitores. Aceitei-o de bom grado por se tratar de um elenco de obreiros culturais com quem doravante poderei colaborar mais estreitamente. E, pela obra feita, os meus parabéns e votos de longa vida à Casa e à sua Direcção.

Para além desses laços que me unem à Revista da Casa de Goa, é a própria terra e cultura de Goa que me acenam. Vivo no meu torrão natal, porém, não pretendo conhecê-lo melhor do que outros que não têm esse ensejo. E nem se pode dizer que os que se ausentam por força das circunstâncias têm menos amor à terra dos seus antepassados. No nosso caso, o que vale é ter o coração sempre a bater por Goa.

Mais. Não é somente o sangue que determina a cidadania cultural. Goa, que conheceu outros povos e culturas, poderia comprovar que no decurso da sua longa história foram muitos que se apaixonaram por ela. Ainda hoje, há pessoas que têm um enternecedor amor, dir-se-ia mesmo uma ligação espiritual com ela. A nós cumpre enaltecer e perpetuar o que há de nobre nesse talismã que se chama Goa.

Podemos dizer, sem receio de errar, que Goa é ao mesmo tempo terra e estado de espírito. E quem somos nós? Na feliz frase de António Colaço, “somos uma pequena e grande família. Não há aqui hindus, moiros ou cristãos. Há só Goeses”. Importa salvaguardar a nossa irmandade, deixando-a viva tanto em Goa como em Lisboa, enfim, em todos os lugares onde se encontram os Goeses, desde os tradicionais kulls ou clubes nas metrópoles indianas até às associações culturais e desportivas dos goeses espalhados pelo mundo.

Neste particular, devem Goa e Lisboa assumir um papel de liderança. Essa liderança se impõe pelo facto de serem elas os pilares da universal Casa e Espírito de Goa. Graças a Lisboa, a minúscula Goa foi em tempos o ponto de encontro do Oriente e Ocidente: aí se fundiram as culturas lusa e indiana; aí dois mundos se trocaram; aí se deu aquilo que Gilberto Freyre designou de “milagre sociológico”. Goa e Lisboa foram mesmo precursores da globalização.

Fica assim bem clara a acção pioneira que tiveram Goa e Lisboa no conhecimento mútuo das sociedades e culturas. Em ambas as cidades o elemento local se tornou universal, e vice-versa. Como agentes de transformação dos povos que mal se conheciam; como modelos de paz e amor fraterno, Goa e Lisboa têm os seus nomes escritos em letras douradas. Só que jamais se pode falar de amchém bhangarachém Goem – “nossa Goa dourada” – nem Lisboa se pode gabar de capital cultural sem problemas.

Nessas voltas que o mundo dá, festejemos a nossa identidade, cantando os louvores à língua e literatura, música e arquitectura, indumentária e culinária, às nossas seculares instituições e tradições, mas reconheçamos também as novas realidades…. Aquilo a que chamamos Goa, existe ela na realidade, ou é uma simple miragem? Se existe, até quando será ela goesa? E esse espírito, estaria ele claro ou cada vez mais nebuloso?

Nesse sentido, urge uma conscientização e relevante acção. Consistiria em viver com amor ao torrão natal; valorizar o seu património; salvar o meio ambiente; cultivar as terras com engenho e alegria; e acima de tudo, participar activa e patrioticamente na governação, com plena consciência dos valores subjacentes à cultura goesa.

Nesta Revista e noutros lugares, enquanto delineamos o nosso ideal, trabalhemos com os corações unidos em volta desta louvável causa comum.

(Editorial na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Serie, N.º 6, Set.º-Out.º de 2020)

https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:80665fef-61a8-44bb-988a-e697ace84c22

Mapping Goa's Architecture

Goa - A Traveller's Historical and Architectural Guide, by Antony Hutt. Scorpion Publishing Ltd, England. Rs 200

It could well be called a serious work written for the casual traveller. More specific academic exercises have preceded this one since the 1950s but the highlight of Antony Hutt's book is his comprehensive treatment of Hindu, Christian and Muslim architecture – civil, religious and military.

Out of the nine chapters the first five are devoted to the history of Goa – right from the early times down through the Hindu and the hitherto neglected Muslim period, up to the Portuguese connection, when Goa got to partake directly of the history of the modern world. However, the 20th century is almost entirely left out.

The historical account is highly readable, largely chronological, though desultory at times. Refreshing it is to find the history of tiny Goa placed in the larger context of the history of India and the world. Hutt is well disposed towards the Portuguese, the Inquisition notwithstanding, and is of the opinion that they "inaugurated the most brilliant period in her history".

Old Goa alone becomes the subject of chapter 6. The Indian Baroque church of the Holy Spirit (St Francis of Assisi), the church of Our Lady of the Rosary, St Catherine, the Cathedral See, Grace Church (St Augustine's), the Royal Chapel (St Anthony), St Monica Nunnery, the convent of St John of God, the Minor Basilica of Good Jesus, St Cajetan, church of Our Lady of the Mount, the Viceroys Arch, and the Archaeological Museum – twelve monuments, all of them mapped. Good treatment this but no real revelations whatsoever.

The next few pages are devoted to Portuguese architecture outside the capital city. This is followed by a novel chapter on the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture.

It is in the following chapter that the author is least original in what concerns civil and religious architecture. Salcete, and more in particular, Loutulim, forms the main thrust, and what follows is a routine description of only the better known houses in Salcete – the da Silva mansion in Margão, the Miranda and Figueiredo houses in Loutulim and the Menezes Bragança in Chandor, the only exceptions this time being the Salvador Costa house in Loutulim and perhaps also the Souza Gonçalves and Albuquerque mansions in Bardez.

On the other hand, a novelty is certainly the description of the forts of Goa: Tiracol, Chapora, Aguada, Reis Magos, Gaspar Dias, Cabo, Marmagoa, Cabo de Rama and the inland fort of Santo Estevam, all find their rightful place in Hutt's book.

In contrast with the earlier chapter, what constitutes a real contribution is Hutt's elaboration of the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture. It is, however, most unfortunate that there is not a single picture of any of the six Hindu houses described – the Sinai Kundaikars in Kundai, the Ranes in Sanquelim, the Khandeparkar house in Khandepar, the Dempo and Mhamai Kamat houses in Panjim and the Deshprabhu palace in Pernem. We are only left to imagine what they really look like.

More than nine temples are included, the earliest being the rock-cut sanctuaries of the 3rd-6th centuries A.D., most of which are Buddhist in origin; Sri Mahadeva temple, Tambdi-Surla; Shiva temple (Curdi), Saptakoteshwar (Naroa); Mahalsa, Mangueshi, Shantadurga; Kamakshi (Siroda), and Mahalaxmi (Bandora). There are specific references to the "odyssey" of many Hindu deities of Goa.

Hutt was in love with Goa and visited it often from the 1970s to the 80s. He could not then possibly miss out a comment on the life of the Goan people. And the final chapter is just that, a paen to the Goan genius: the warmth and colour of the people, the traditional communal harmony, and so on. But this sociological exercise should have been accompanied by a more definite statement on the nature of popular architecture in Goa – a point that is sacrificed at the altar of elite architecture, so to say.

A good bibliography can serve as a delicious dessert for the curious mind. Sad to say, here the book is a complete let-down. The scanty information cannot satisfy even the least curious of travellers/readers. There is not even a minor reference to the works of Mário Tavares Chicó or Carlos de Azevedo from Portugal nor to the historical works of Danvers, Gabriel de Saldanha or José Nicolau da Fonseca. Rather mysterious references are made to books published after the author's death, and for that matter, other books figure in the bibliography from which not a line or illustration is traceable in the text. Also missing is a detailed map of Goa.

All in all, an impressive book. Good get-up, fine printing. For certain shortcomings of the text, every reader would be willing to make certain concessions given the author's premature death in 1985.

(Goa Today, November 1989)

Our Honoured Guest

The directive from the Union Home Ministry to give the loving last Portuguese Governor-General, General Manuel Antonio Vassalo e Silva, a “warm welcome” and a “foreign dignitary VIP treatment” is to be admired as the Government showed their love and respect to that person who earlier pictured his fine sensibilities to Goans whom he so dearly loves.

But, at the same time, there seemed to be a few of our own people who although owing so much to Gen. Vassalo tried to misunderstand the Government: A “warm welcome” (the Government’s call) doesn’t only mean giving a beautiful bouquet of flowers to the visitor at the airport but still more, it emphasizes the need for a good treatment during his stay in this place.

Although all plans for a “warm welcome” were made well in anticipation by our Speaker, Mr Froilano Machado, there was something unhappy awaiting Gen. Silva at the Azad Maidan, when he went there to place a wreath at the Martyrs’ Memorial, much to the surprise and dislike of hundreds of Goans worthy of Mr Silva’s kindness: it was a dharna, a protest with black flags against the ex-Portuguese Governor-General’s visit to Goa; he who did so much good for us Goans. That should not even have been thought of because Gen. Silva was invited by Goans who intend to manifest their love and gratitude towards him. Secondly, what has Mr Silva to do with the integration of Goa into the Indian Union? Is Mr Silva responsible for Salazar’s misdeeds?

On the other hand, if any Goan had to open his heart and say something genuine against the Portuguese he would have done so or should have done so by approaching Gen. Silva in a very gentlemanly manner and not by what we witnessed at the Azad Maidan. This sort of behaviour from the Goans who are known for their non-aggressiveness and kindness is unthinkable.

Keeping aside the misbehaviour of a handful of people, I would like to mention that there were many also who openly showed their consideration for the Portuguese: one was an aged woman who respectfully wished the popular ex-Governor-General who then spoke very emotionally to her. A few steps further, some others waited to salute and talk to the octogenarian, who recalled his good old days with them in Goa.

We congratulate Gen. Vassalo e Silva who gave out the truth that Salazar didn’t ask him to destroy but to “defend it to the last”. This will remove the misconceptions about the affair.

Kudos to the editorial which has described Gen. Silva very well as a man to whom we ought to be grateful.

(Letter to the editor, The Navhind Times, Panjim, 12 June 1980, p. 2)