Prayer must be a way of life

To every believer whose desire is to know how to pray, here are some heart-warming pointers: in today’s Gospel (Lk 11: 1-13) we have a formula par excellence, and in the First Reading (Gen 18: 20-32), an illustration of how to pray. It is not ours to reason why, for if we are to survive, praying must come as easy as breathing. As Alexis Carrel, Nobel Laureate for Medicine, puts it: ‘Simple souls feel God as naturally as they feel the heat of the sun or the fragrance of a flower; but the same God, accessible to those who know how to love Him, remains hidden from those who do not understand Him.’

Abraham had no difficulty in relating to God who visited him in human form. They talked about Sodom and Gomorrah that were slated for severe punishment for their grossly offensive conduct. That is when Abraham began to do a deal with God, like a child would with his parents: he was concerned about the safety of his nephew Lot who had relocated to Sodom in a huff. Abraham left no stone unturned to secure a good ‘bargain’ as only he can do who knows God intimately.

Thankfully, Christian mystics from St Paul down to St Padre Pio have elaborated on kinds, methods and levels of prayer, and offered formulas; but none of them are crucial, for a child talking to his parent follows no fixed action pattern. The best policy is to be our honest selves, ready to do our Father’s will in all things, as the ‘Pater Noster’ counsels. While St Augustine reportedly said that he who sings, prays twice; St Aloysius of Gonzaga believed that work is prayer. Which goes to show that it is of the essence to establish a hotline with God and not merely employ a certain formula or method.

That God finally took a softer line at Abraham’s instance should be an eyeopener to those who doubt the efficacy of prayer! Such doubts stem from a secular attitude or a spirit that excludes God from our life. It is clear from today’s parable that God wants us to ask and persevere in the asking – while all the time believing with The Imitation of Christ, that ‘Man proposes; God disposes.’ And how can we forget the words of Our Lord Himself: ‘Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and it will be opened to you’!

Of course, that promise comes with a rider: we must have a change of heart; deep faith and trust in God; and pray calmly, humbly and confidently. We must praise and thank God, petition Him and intercede for others. When we leave it to Him to fix our broken lives soon we will hear our lips sing, ‘Lord, on the day I called for help, you answered me… Your kindness, O Lord, endures forever; forsake not the work of your hands.’ We have the Lord’s promise: ‘If you then, who are wicked, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask Him?’

Of course, that promise comes with a rider: we must have a change of heart; deep faith and trust in God; and pray calmly, humbly and confidently. We must praise and thank God, petition Him and intercede for others. When we leave it to Him to fix our broken lives soon we will hear our lips sing, ‘Lord, on the day I called for help, you answered me… Your kindness, O Lord, endures forever; forsake not the work of your hands.’ We have the Lord’s promise: ‘If you then, who are wicked, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask Him?’

But is that all as simple as it sounds? It is so if we do not let sin snap our hotline with God. At any rate, the Sacraments that can help restore it. We also need to create the right physical and psychological conditions to communicate with the Creator: for instance, personal prayer in the privacy of our rooms, and communal prayer in the sacral ambience of our churches. Notice how the interior of a monastery or the protected area of Old Goa or even a quiet and sprawling campus like Don Bosco’s situated in the middle of Panjim city can set the tone for a divine encounter: they are oases of tranquillity fit for the angels of India!

Although forces of evil are pressing against us, we must not be disheartened. St Paul in the Second Reading (Col 2: 12-14) puts things in perspective when he says that God has given us the ultimate gift of love through His Son Jesus Christ, thus securing us a return to the One we are united to through Baptism. So, even if our outer shell be diseased, the core of our being finds healing through prayer. We remain insulated against the fear of suffering, sickness and death if our life be a prayer offered to God, ‘an elevation of our soul to God’ (Tanqueray, The Mystical Life, cit. The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality, p. 765), a way of life!

Active and Contemplative

Do you wake up listless and dejected, upset about things not going your way? Do you dismiss a brand-new day as just another ordinary day? Well, if we give time to time, we might suddenly see things changing unexpectedly. What’s more, we will find that all things are possible – especially the impossible – when we are sustained by God’s Word! That’s putting things in perspective.

In the First Reading (Gen 18: 1-10), we are privy to a miracle. If Abraham, kind and obliging even at a ripe old age, seems to be without a worry in the world, it may help to know that he and his wife Sarah were heartbroken but had lovingly come to accept their situation. Abraham obliges his guests, not because he sees something in it for him but because he is an honourable man. The threesome leave before long – but not without announcing the good news that Sarah will bear a child. No doubt she laughs it off (note that Mary in her own case wondered, ‘how can this be’!) – but so it is: she gives birth to Isaac, a name that means just that: ‘he who laughs’ or ‘he who rejoices’! In short, nothing is impossible with God!

The Gospel (Lk 10: 38-42) has a matching situation. Here, Jesus is hosted by Martha and Mary. The elder sister’s busy chores are her presents for Jesus; the younger one, awestruck by every word that Jesus utters, honours Him with her presence. Truly, if simple living and high thinking is what a self-respecting guest values, it is more so Jesus, who is always about His Father’s business. Mary makes these words her own: ‘Speak, Lord, your servant hears; you have the words of eternal life.’ And Jesus praises her, for she has ‘chosen the good portion, which shall not be taken away from her.’

My dear departed grandmother used to say that faith and education none can take away from us. After all, that is what matters, for man does not live by bread alone but by every word that comes out of the mouth of God. So, when it is the Living Word alone that can sustain us, why settle for less? But alas, how often do we think of God in our everyday chores? How zealously do we mention Him at our glitzy social gatherings? How well do we recognise the voice of God in our daily encounters? Note that if Abraham were to despise the three men – seen as God Himself with two angels or, alternatively, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit – the ‘Father of Many Nations’ would have been father of none. Like Abraham, let’s get our priorities straight!

My dear departed grandmother used to say that faith and education none can take away from us. After all, that is what matters, for man does not live by bread alone but by every word that comes out of the mouth of God. So, when it is the Living Word alone that can sustain us, why settle for less? But alas, how often do we think of God in our everyday chores? How zealously do we mention Him at our glitzy social gatherings? How well do we recognise the voice of God in our daily encounters? Note that if Abraham were to despise the three men – seen as God Himself with two angels or, alternatively, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit – the ‘Father of Many Nations’ would have been father of none. Like Abraham, let’s get our priorities straight!

Can we rightfully say with St Paul in the Second Reading (1 Col: 24-28): ‘I rejoice in my sufferings for your [the Colossians] sake, and in my flesh [through his body] I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the Church’? As Christians, we are duty-bound to shun sadness and joyfully put our belief, hope and trust in the Lord – and then go on to love God and our neighbour as ourselves. We must stand firm for ever, as the Psalm says; if not, how will we admitted to the holy mountain?

To conclude, if all work and no play make Jack a dull boy, imagine how dull – and empty – we should feel if we always work and never pray! Let us make it a point to set aside quality time for God, listen to His voice and do His holy will. Let us delight in the presence of God and bless His Holy Name. Let’s not get too caught up with worldly things; rather, like Mary, let’s choose the good portion, and everything will fall in place. Let us balance action with contemplation.

Just as Jesus was not going to be with His friends for too long, we too will not live too long on this earth, will we? Let us, then, receive God in our hearths and homes today, so He recognises us tomorrow, when we knock on Heaven’s door!

Being a Good Samaritan

Who can deny that the world would be a better place if we followed God’s commands to the hilt? No doubt, sincere people take to them like fish to water; they don’t find them difficult to follow, ignore them, play up or spurn them. The natural moral law is etched on our minds and we know it by heart. As the First Reading (Deut. 30: 10-14) says, ‘The Word is very near you: it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it.’ In the modern lingo, we are hardwired to love God’s law and must beware of worldly-wise, pirated software designed to infect the system!

God is not crazy or eccentric; His law is not ‘out there’, unusual and unconventional. He has had covenants with us, but alas, we have failed to honour them! In days of old, God spoke directly to His people or to a prophet. But then, being invisible had its flip side: God began to seem distant; so, He sent His Only Son to be born of a Virgin. Jesus walked the earth, spoke the language of the land, worked out miracles to everyone’s amazement, and died for our sins in an unprecedented outpouring of love. The essence of his parting message was that we love God and neighbour.

But isn’t that easier said than done? In the Gospel (Lk 10: 25-37), a Jewish scriptural scholar, after admitting that one can inherit eternal life only by loving God (Deut 6: 5) and neighbour as oneself (Lev 19: 18), demands to know who is our ‘neighbour’. His question makes sense for, to the Jews, only a member of their religion or race was a ‘neighbour’. The scholar probably wished to hear a novel definition that would navigate through issues like religion and ethnicity (Jews/Gentiles) gender and class (clean/unclean). Instead, Jesus responded with a parable that unimaginably expanded the scope of the term; and He topped it up with a question that dispelled all doubts!

In that touching and famous Parable of the Good Samaritan – reported by St Luke alone – he who attended to that half-dead man, with compassion, was from a region that the Jews looked down upon, thanks to their mixed ethnicity and their worship outside Jerusalem. Yet, Jesus introduces us to an individual Samaritan whose behaviour is a far cry from that of the Jewish priest and the Levite (temple assistant from the Hebrew tribe of Levi). Were these two too busy to stop and help, or were they merely playing it safe, for touching a dead man would prevent them from carrying out their temple duties! Or maybe not, for Jesus talks about them going from Jerusalem to Jericho, and not the other way around. While Jesus leaves the backstory a mystery, we can rest assured that God had moved the Samaritan to set an example to generations to come!

Which brings us to the Second Reading (Col 1: 15-20) in which St Paul emphasises that Jesus alone can inspire and help us humans to love and serve. The Apostle of the Gentiles portrays Christ as the mediator between Creation and Redemption: He who was present at the time of the creation of the world will also be the One through whom the world will be redeemed. Shouldn’t He, then, be the focus of our life? Our life makes sense only through Him. Note the repetition of the word ‘all’ in the passage: the writer wishes to emphasise the fact that there is nothing outside Him who is the Way, the Truth and the Life. He is the be-all and end-all of our existence. This reality can never be emphasised enough, lest we begin to sacrifice the truth of the Gospel to the distorted values of the contemporary world.

The values of the contemporary world are centred on money, influence and power. They keep us bonded; they prevent us from reaching out to others in love, as Jesus did. Subservience to the material world is a despicable form of bondage that only God’s laws have the power to liberate us from. Hence, Jesus alone is deserving of our trust and confidence; He is our only model for doing things through love. So, it is not good businessmen but Good Samaritans are God’s instruments of hope – fools for Christ, in this mad, mad world!

However, being a Good Samaritan does not mean being naïve; it does not demand suspension of our critical faculties. In the near-Godless world we live in, steeped in malice and misunderstanding, Good Samaritans must indeed act with discernment. Wherever we may find ourselves – be it at home or at work; in a school or a hospital, in the street or on the battlefield – reaching out to our neighbour is of the essence. One sure way of doing this is to ward off pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath, and sloth. When we evict those seven trespassers, God comes into our minds and hearts, moving us to be Good Samaritans in a way that is most pleasing to Him.

On the mission field

Today’s readings grab our attention: the first, by Isaiah’s colourful imagery (Is 66: 10-14); the second, by St Paul’s passionate testimony (Gal 6: 14-18); and, of course, the third by Jesus’s stirring voice (Lk 10: 1-12, 17-20). Close on the heels of last Sunday’s Gospel passage, which invited us to be resolute in disseminating God’s Word, Our Lord brings into sharp focus the mission of His disciples – which is our mission too!

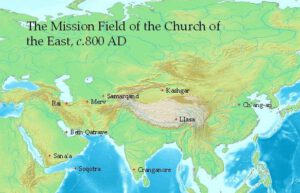

Coincidentally, in India, 3 July is the Solemnity of St Thomas, the Apostle. The readings proper to the occasion are from Acts 10: 24-35; Heb 1: 2-3 or Pet 1: 3-9; and Jn 20: 24-29, whose last sentence from the mouth of Jesus is ‘Blessed are those who have not seen, and yet believe’. However, we are going to comment on the readings proper to the universal Church; by God’s grace, they also fit like a glove, dwelling as they do on the life of a missionary, which St Thomas was one par excellence.

A fragment of today’s Gospel reading rings in the ear of every believer: ‘The harvest is plentiful, but the labourers few.’ How many did Jesus commission? Some codices say seventy, others seventy-two: both figures are right, as they represent the pagan communities (70 in the Hebrew text, 72 in the Greek) mentioned in Genesis 10.

St Luke is the only Evangelist who makes a mention of this number, suggesting that Jesus would not limit Himself to the twelve tribes of Israel (denoted by the Apostles) but would reach out to all communities and nations. One of them, St Thomas, travelled to South India and died there. And as members of the Church today, it is our responsibility, until the end of the world, to evangelise like them, without fear or favour.

It is noteworthy that Jesus spoke to the seventy-two after He had spoken to the Twelve (see Lk 9). Thus, the Gospel was proclaimed first in Israel and thence to others. Jesus commanded the disciples to go ahead of Him into every town and place. That He sent them out ‘as lambs in the midst of wolves’ spoke volumes of the trials and tribulations awaiting them in a hostile world. Yet, He bid them to carry no purse, no bag, no sandals, and to salute none along the way: He expected them to trust in Him alone.

The disciples also received some practical tips from the Divine Master. They were not to waste time in elaborate greetings, so typical of Oriental cultures, but to focus on announcing the Good News without delay. The disciples were to eat, drink and accept accommodation as provided to them, for the labourer deserves his wages; but they were not to have expectations or make demands – for God would sustain them. They had to reach out to the sick – not only physically but spiritually – by giving them the hope of eternal salvation.

Jesus made an interesting distinction between what was to be the disciples’ behaviour in a household and in a town per se. Not only would their greetings differ, but their attitude as well. If an individual or his household refused the disciples, the latter’s response would be milder than when a town rejected them. In the latter case, Jesus recommended that they shake off the dust of their feet. He promised them authority over the enemy and that their names would be written in Heaven. The disciples fulfilled their mandate diligently and, no wonder, they returned with joy.

If Our Lord’s occasionally tough language does not match that goody-goody image of Him, let’s remember Jesus was not a goody-goody; He called a spade a spade, was earnest about his Father’s holy business and brooked no nonsense. Thus, the peace His disciples carried went beyond mere greetings of good health and prosperity; it was a messianic peace. And the hard-hitting words that Jesus and His disciples uttered were but messianic lamentations, for the fate that awaits detractors is one worse than Sodom’s.

If Our Lord’s occasionally tough language does not match that goody-goody image of Him, let’s remember Jesus was not a goody-goody; He called a spade a spade, was earnest about his Father’s holy business and brooked no nonsense. Thus, the peace His disciples carried went beyond mere greetings of good health and prosperity; it was a messianic peace. And the hard-hitting words that Jesus and His disciples uttered were but messianic lamentations, for the fate that awaits detractors is one worse than Sodom’s.

Jesus expects us to adopt a like posture; we are not to trivialise God. St Paul, who witnessed similar crises in the communities he tended, concludes his letter to the Galatians, by stating that salvation lies only in the Cross of Christ: ‘I do not wish to take pride in anything except in the cross of Christ Jesus our Lord,’ he said unequivocally. This is an eye-opener for us who we must learn to guard against sacrificing the truth of the Gospel to materialistic values and goals. Let us not doubt, let us not harden our hearts when we hear the Lord’s words.

We who have had the fortune of meeting our awesomely loving God must proclaim His works. The prophet Isaiah fashioned most beautiful images to give us an idea of God’s unfathomable love: it is like that of a mother for her child; of a husband for his wife; of a bridegroom for his bride. We too must acknowledge God’s omnipresence, omniscience and omnipotence. We must strive to be true disciples of Christ, the salt of the earth and light of the world. We must not hide the light under a bushel but set it upon a lampstand so that it radiates light to all in the world.

If we announce what God has done for our souls with true missionary zeal, the world will cry out with joy and sing glory to His name!

All for the greater glory of God

What is our response to God who has lovingly revealed Himself in myriad ways on three successive Sundays? The Mass readings of today are an apt reminder of what should be our posture vis-à-vis the purpose of our existence.

In the First Reading (1 Kings 19: 16B, 19-21), we meet Elijah, a prophet who lived in Israel nine centuries before Christ. He defended Yahweh, the one true God of the Israelites, against Baal, a false god of the Canaanites. God worked miracles through Elijah as a sign that he was His favoured one. He was bodily assumed into heaven on a chariot of fire; and at the time of the Transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor, he too appeared, along with Moses. It is said that he will return before the last day, as a harbinger of the Saviour.

Before his departure, Elijah had made sure that Elisha would step into his shoes as prophet. The cloak thrown over Elisha symbolised the transfer of Elijah’s very persona, with all the rights and charisms of his vocation. Elisha spent some time on Mount Carmel (hence, a favourite with the Carmelites) where Elijah had once lived and challenged the prophets of Baal. Not everything that these two distinctive figures did is documented, but one thing is sure: they were clear about what was expected of them and faithfully carried out their missions.

How beautifully this links to the Gospel (Lk 9: 51-62), which urges each one of us to readily respond to God’s call, like Elisha did. Here, Jesus presents us with three injunctions, veritable pearls of wisdom; though not uttered in quick succession, in real time, St Luke stringed them together thematically. When Jesus was refused accommodation by a Samaritan village, in keeping with the customary animosity with the Jews, our Saviour commented on it pointedly, in three pearls of spiritual knowledge.

How beautifully this links to the Gospel (Lk 9: 51-62), which urges each one of us to readily respond to God’s call, like Elisha did. Here, Jesus presents us with three injunctions, veritable pearls of wisdom; though not uttered in quick succession, in real time, St Luke stringed them together thematically. When Jesus was refused accommodation by a Samaritan village, in keeping with the customary animosity with the Jews, our Saviour commented on it pointedly, in three pearls of spiritual knowledge.

The first of the pearls is a lament on how ‘foxes have dens and birds of the sky have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to rest his head.’ That is, while the least of creatures, if worldly-wise, are well received, those who have an other-worldly outlook, even if thinking logically and acting fairly, are made to feel unwelcome.

That is how fallen man behaves; hence the second pearl, in the form of a piercing arrow: ‘Let the dead bury the dead,’ says Jesus, and bids us to single-mindedly get going with God’s business. And then comes the third pearl, as a tough challenge: ‘No one who sets a hand to the plough and looks to what was left behind is fit for the kingdom of God.’ Jesus warns us against pinning our hopes on the world; we rather be steadfast in divine matters.

Meanwhile, will we ever overcome our innate love for the world and all that is in it? Is it possible to tread the path that Jesus points to? Will its difficult terrain not cause us untold hardship and misery?

We have it on excellent authority that God has called us for freedom – and only He can set us free! St Paul in the second Reading (Gal 5: 1, 13-18) says, ‘For freedom Christ set us free; so, stand firm and do not submit again to the yoke of slavery.’ The Apostle of the Gentiles, who had freed the Galatians from the oppressive Mosaic law, wanted them to hold fast to their newfound, Christian freedom that liberates one not only from the yoke of law but from the yoke of sin as well. Alas, how we underestimate that freedom!

On the other hand, how are we to conduct ourselves? Like Elisha, of course! He who heeded God’s call asked for time only to slaughter his oxen and burn the very plough. Elisha was in the right frame of mind; he trusted the Lord and renounced everything. For our part, how about asking for the gift of discernment to help us separate the wheat from the chaff?

Not that it will set us rolling on a comfortable highway; life will mostly likely remain the same narrow path it always is, filled with trials and tribulations. But surely, our slow and steady daily grind will liberate us from the yoke of egos and taboos; our suffering will gradually score a victory over evil tendencies, purify and sanctify us. And when we have run the race, having kept the faith, we will gladly have followed Jesus, who is the Way, the Truth and the Life.

Finally, if all of the above seems silly or extreme, consider why we find the world in a shambles today! It is because we have lost sight of the primary reason of our being, that is to seek God and know Him, to love God and serve Him, ‘above all nature and all created things.’ We have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. Let us, then, quickly turn around and live our lives ad majorem Dei gloriam – as the motto of Ignatian spirituality says – for the greater glory of God!

Bread Broken, Wine Shared

In June we celebrate three important solemnities – Pentecost; Holy Trinity; and the Body and Blood of Christ. These solemnities held on three consecutive Sundays form a kind of triptych drawing our attention to those central mysteries of our faith. The first solemnity helps us see the Holy Spirit at work in the Church; the second focusses on the Triune God whose Source is the Father; and the third highlights the Son’s Real Presence in the Eucharist. These solemnities are all so rich in meaning that if we only stop to understand their significance, our faith can easily take on a deeper reality.

Today’s Solemnity, which used to be called Corpus Christi (Latin for ‘the Body of Christ’), is now known as the Body and Blood of Christ, more in keeping with the Eucharistic theology. Really speaking, the solemnity falls on a Thursday after that of the Holy Trinity; but, in India, both solemnities have been moved to the Sunday following, to enable a more worthy celebration. Similarly, the shadow of the Cross falling on the liturgy left little scope to celebrate the institution of the Eucharist on Maundy Thursday. Hence, way back in the 13th century, the Church found it appropriate to bathe the solemnity in the paschal joy.

It is common knowledge that the fateful Thursday that marked Jesus’ final Passover comprised a meal to mark the Jewish thanksgiving to God for delivering the people from slavery in Egypt. That meal, now known as the Last Supper, instantly assumed a new meaning when Jesus proclaimed a new commandment of Love; instituted the Priesthood; and established the Sacrament of Holy Eucharist. Thus, over and above the thanksgiving, the Eucharist involves our participation in Jesus’ eternal Priesthood and a re-enactment of His Sacrifice on Calvary.

The multifarious connotations of the Eucharist are reflected in the day’s readings. In the First Reading (Gen 14: 18-20), we meet a mysterious figure, Melchizedek, king of Salem (presumed to be Jerusalem) and priest of God Most High, on his way to bless Abraham who was returning from a just war. In his thanksgiving to God, Melchizedek offers bread and wine, a common food and drink for the Jews. Christian tradition sees Melchizedek as prefiguring Jesus, who is Priest, Prophet and King; and his offering, in the mould of the Eucharistic Sacrifice.

The Second Reading (1 Cor 11: 23-26) refers to the Eucharist instituted by our Lord. St Paul’s writing of circa A. D. 55 predates the Gospels and is the oldest testimony relating to the Last Supper. Jesus breaks the bread, symbolising His Body, and raises the Cup, symbolising His Blood. He does this for us in love beyond compare and bids us to repeat it as a memorial. So, there is an ineffable union with Jesus Who is present at every Eucharistic celebration.

Finally, St Luke’s Gospel (9: 11-17) talks about the remarkable meal that fed five thousand who had gathered to listen to Jesus. This is evocative of two passages from the Old Testament: the feeding of the Israelites in the desert and of Elisha’s feeding a hundred people with twenty loaves. They herald the Eucharist as food and medicine for the body and soul.

A deeper reality underlies the Holy Eucharist: the miracle of Transubstantiation. When the priest consecrates the bread and wine, ‘there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood.’ (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1376) The species do not change in appearance but turn into the very essence, reality and matter of the Lord’s Body and Blood. It is the Lord’s Real Presence – dwelt on by the encyclical Mysterium fidei.

The Eucharist is indeed a ‘mystery of faith’. St Thomas of Aquinas states that this ‘Sacrament of sacraments’ (CCC 1330) ‘cannot be apprehended by the senses but only by faith. Before him, St Cyril of Alexandria advised: ‘Do not doubt that this is true; instead accept the words of the Saviour in faith; for since He is truth, He cannot tell a lie.’ (cf. CCC, 18) To those who seem unconvinced, the ‘Eucharistic Miracles’ are most likely to provide satisfactory proofs (cf. Eucharistic Miracles and Eucharistic Phenomena in the Lives of Saints, by Joan Carroll Cruz)

As we take a leap of faith and humbly surrender ourselves, the Lord of the Eucharist will reveal Himself to us sooner rather than later. The Eucharist, so rich in symbolism, will bring meaning to our lives. And as we gradually enter into full communion with Him and open ourselves to His Mystery, God will protect the sacred mystery of our lives. In the words of Pope Benedict XVI in his apostolic exhortation Sacramentum caritatis, ‘It is through the working of the Spirit that Christ himself continues to be present and active in his Church, starting with her vital centre which is the Eucharist.’ That's a wonderful lesson from June’s Mystery triptych!

Discovery of God

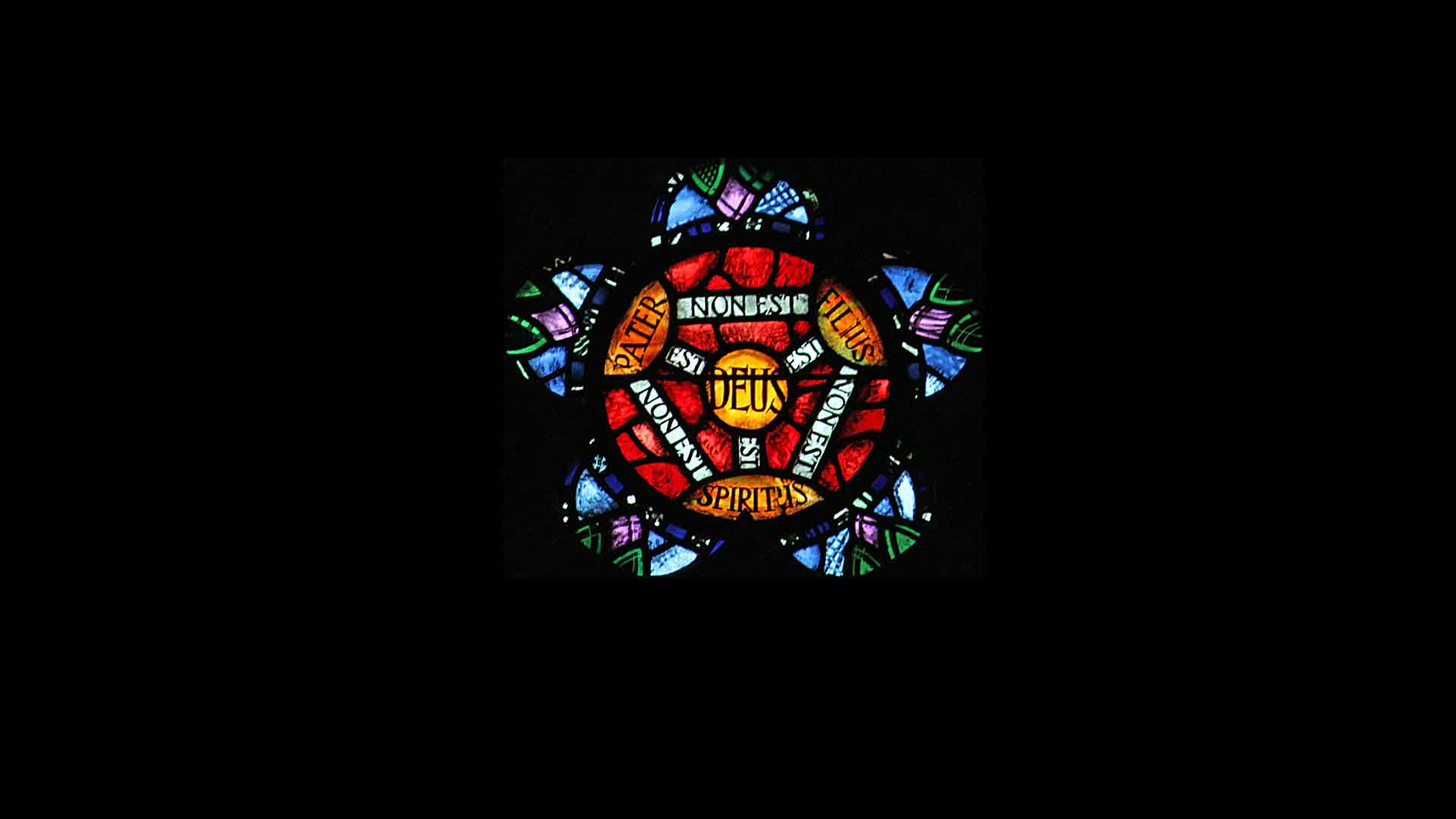

On Pentecost Sunday, we gladly encountered the Holy Spirit. Now it is only natural that the Most Holy Trinity should be in full view. This is the Solemnity we celebrate today.

It may come as a surprise to many that it is not the Incarnation, nor even the Resurrection, but the Holy Trinity that is Christianity’s central mystery, from which flow all the other mysteries of our faith. It is a mystery that has existed since the beginning of times but has unfolded only gradually.

For instance, the Old Testament has references to the Three Persons but stops short of stating a Trinitarian doctrine. In the New Testament, Jesus pointed to His Father who loves us and desires our salvation; He presented Himself, the Son, as the Way, the Truth and the Life; and, before His departure from the world, He announced that the Holy Spirit would reside in our souls as a Guest. Yet, a doctrine of the Triune God was far from clear and remains to date just that: a mystery, a belief beyond our ability to understand unless God bares it to us.

None can deny, however, that the Trinity has been progressively revealed to humankind down the ages. It was not disclosed all at once, not only because of the finiteness of human minds, but because God patiently waits for us to exercise our freedom and come forward to learn about the intimate life of God. It is never an imposition; it is rather an invitation to establish personal ties with the three divine Persons.

That is what happened after Jesus. The early Christians felt it necessary to decode the Risen Lord’s instruction to make disciples of all nations, baptising them ‘in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit’. They also pondered St Paul’s blessing – ‘The grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all’ – now recited in the introductory rites of the Holy Mass. By and by, Biblical references to Father, Son and Spirit were put together as a cohesive doctrine.

In spite of all that welcome research, the Holy Trinity remains the most difficult theme of our faith. Today’s readings bear it out: they give only a glimpse, not a precise understanding of the mystery. In the First Reading (Prov 8:22-31), we hear Wisdom rather than God the Father speak. Anyway, God – who has defined Himself as ‘I am who I am’ – is Himself Wisdom, and is it not more graceful to be introduced by another than to introduce oneself? So, it is age-old Wisdom presenting the Eternal Father to us. Most importantly, we learn how He is not a distant God but One who delights in communicating with humankind.

In the Second Reading (Rom 5:1-5), St Paul talks of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, who gives us peace that no other can give. He also refers to the Father in whose glory we can hope to share by the merits of His Son’s Death. However, this supreme sacrifice has not eliminated human suffering from the face of the earth. The Apostle of the Gentiles urges us, therefore, to rejoice, for indeed, suffering produces endurance, character, and finally the hope of receiving a priceless grace: total communion with God.

In the Gospel (Jn 16:12-15), Jesus introduces to us the Holy Spirit, to whom He has entrusted the continuation of His mission till the end of times. The Son of God says, ‘I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now’; He leaves it to the Spirit of Truth to make things clear to those who yearn for the truth. And, whereas many things may forever remain a mystery, it behoves us to keep exploring that which has been revealed. At any rate, we who are created in the image and likeness of God have an infused knowledge and intuitively commune with the divine Family of Three.

What is the significance of today’s Solemnity? It reinforces our understanding of the Trinity. Our baptismal entry into this divine community deepens every time we gather around the Eucharistic Table. Today’s Liturgy is set to make us passionate about discovering our God. Our God is not a solitary Being lost in the dark and infinite space but a communitarian God of life and love, a model for the human family.

What is the significance of today’s Solemnity? It reinforces our understanding of the Trinity. Our baptismal entry into this divine community deepens every time we gather around the Eucharistic Table. Today’s Liturgy is set to make us passionate about discovering our God. Our God is not a solitary Being lost in the dark and infinite space but a communitarian God of life and love, a model for the human family.

No minds however great and no words however eloquent will adequately express this most complex of all Christian concepts and doctrines. The most popular story illustrating this fact is taken from thirteenth century Italian Dominican Jacobus de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea. Accordingly, St Augustine was walking by the shore, meditating on the problem of how God could be three Persons all at once, when he notices a little child scooping water from the sea into a small hole he had dug in the sand. When asked what he was doing, the child answered: ‘I’m emptying the sea into this hole.’ ‘What! The sea is too large for the hole,’ retorted Augustine. And pat came the child’s reply: ‘Indeed. But it is easier for me to empty the sea into this hole than it is for you to grasp the mystery of the Holy Trinity.’

At the time, St Augustine was working on De Trinitate which, quite suggestively, he was unable to complete to his heart’s content. But even though his treatise on the inscrutable mystery remained unfinished he did not give up his discovery of our many-splendored G od. Shouldn’t we take a leaf out of his book?

Ecstatic and fiery at Pentecost

After the Ascent came the Descent. Jesus ascended to the Father on the fortieth day after Easter; ten days later He sent forth His Spirit upon the Apostles, Mary, and other followers of Jesus, about 120 of them who had huddled up at the Cenacle in Jerusalem, for fear of the Jews. They had been continually praying for nine days since the Ascension. (Note that this marvellous event led to the idea of a novena as days of prayer leading up to a feast; and, in particular, the Novena to the Holy Spirit in the run-up to the Pentecost).

How delightful it must have been! That morning, God had timed the descent of the Holy Spirit to coincide with Shavuoth (Acts 2:1–31), which traditionally heralded the wheat harvest. In time, Shavuoth came to mean the seven weeks since the Passover; it was finally replaced by ‘Pentecost’ (from the Greek word pentēkostē, “50th”), which comprises the dramatic arrival of the Holy Spirit, as noted in the First Reading (Acts 2: 1-11). A sound from Heaven, like the rush of a mighty wind, filled all the house. Interestingly, spirit means both ‘breath’ and ‘wind’ in the Hebrew culture!

Even more striking were the tongues ‘as of fire’ that came to rest on each one of those Galilean disciples. Thus ‘ignited’, they began to speak in foreign lingoes, to the bewilderment of the motley crowd from every nation under the sun, who had gathered there on the occasion of the Jewish festival. That is the miracle of Pentecost, which indicates that God wishes to be followed and praised by people from every land and clime – unlike Jewish converts of old who had to promptly renounce their native language and culture.

The Second Reading (Cor 12: 3-7, 12-13) speaks of how the disciples built the Church. As St Paul says, ‘To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good... For by one Spirit we were all baptised into one body – Jews or Greeks, slaves or free – and all were made to drink of one Spirit.’ That is to say, Christians contribute their time and talent for the benefit of the community.

In the day’s Gospel (Jn 20: 19-23), the Holy Spirit gives the apostles gifts and fruits necessary to fulfil the great commission of going out, preaching the Good News of Salvation and being the light to all nations. The power to forgive sins is the greatest gift to the Church, which is never free from sinners.

The Church thus built is the ‘Mystical Body of Christ’, mystical because, in Fulton Sheen’s words, ‘this Body is not physical like a man, nor moral like a bridge club, but heavenly and spiritual because of the Spirit which made it one.’ That it is ‘Christ’s prolonged Self’ can be proved from the Voice from Heaven that said, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ ‘When the Body of Christ was persecuted, it was Christ the Invisible Head Who arose to speak and to protest,’ writes Sheen in his Life of Christ.

The Church thus built is the ‘Mystical Body of Christ’, mystical because, in Fulton Sheen’s words, ‘this Body is not physical like a man, nor moral like a bridge club, but heavenly and spiritual because of the Spirit which made it one.’ That it is ‘Christ’s prolonged Self’ can be proved from the Voice from Heaven that said, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ ‘When the Body of Christ was persecuted, it was Christ the Invisible Head Who arose to speak and to protest,’ writes Sheen in his Life of Christ.

Can there be any doubt that the Church born at Pentecost is the Church we belong to? She enjoys four distinctive marks of life: unity; catholicity; holiness; and apostolicity. The Church is animated by one Spirit; she absorbs and redeems humanity without distinction of race or colour; she is holy as a whole, even if her individual members are diseased; she is apostolic, because she took roots in Christ and her ministry derived from the apostles by a continuous succession.

The deeper significance of Pentecost is that Jesus, who once ‘emptied Himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men’, thereby received His fullness and was glorified. He now lives, teaches, governs and sanctifies us, better than He did in Judea and Galilee – for, as Son of God seated at the right hand of the Father in Heaven, He can reach out to the whole world better than He could when He walked the earth as Son of Man.

Pentecost was an important event in the history of the primitive church and continues to be so in our own times too. After Peter had preached his first homily to the Jews and others, showing how Joel had prophesied the coming of the Holy Spirit, about 3,000 people, cut to the heart by the Crucifixion and enthused by the Resurrection of Our Lord, asked for baptism. Within a few decades important congregations were established in major cities of the Roman Empire. It is not difficult to understand how, centuries ago, our own ancestors, attracted by the Mystical Body, the Bride of Christ, converted to the Christian faith.

The stronger our adherence to the Church, the quicker will be the spread of Christianity in our day and age. Can we imagine ourselves being born outside the Church? No. Let us therefore honour the glorious birthday of the official Church. It is a gentle movement of hearts that still brings together people formerly separated by languages, cultures, races and nations, and will culminate in the Second Coming of Christ. Let’s commit ourselves to putting our lamps on a high stand such that it shines upon all that are in the house. Reaching out to people from the seven corners of the globe is a continual challenge. Let’s be ablaze with love of God and neighbour, and pray, ‘Send us, O Lord, your Spirit, and renew the face of the earth!’

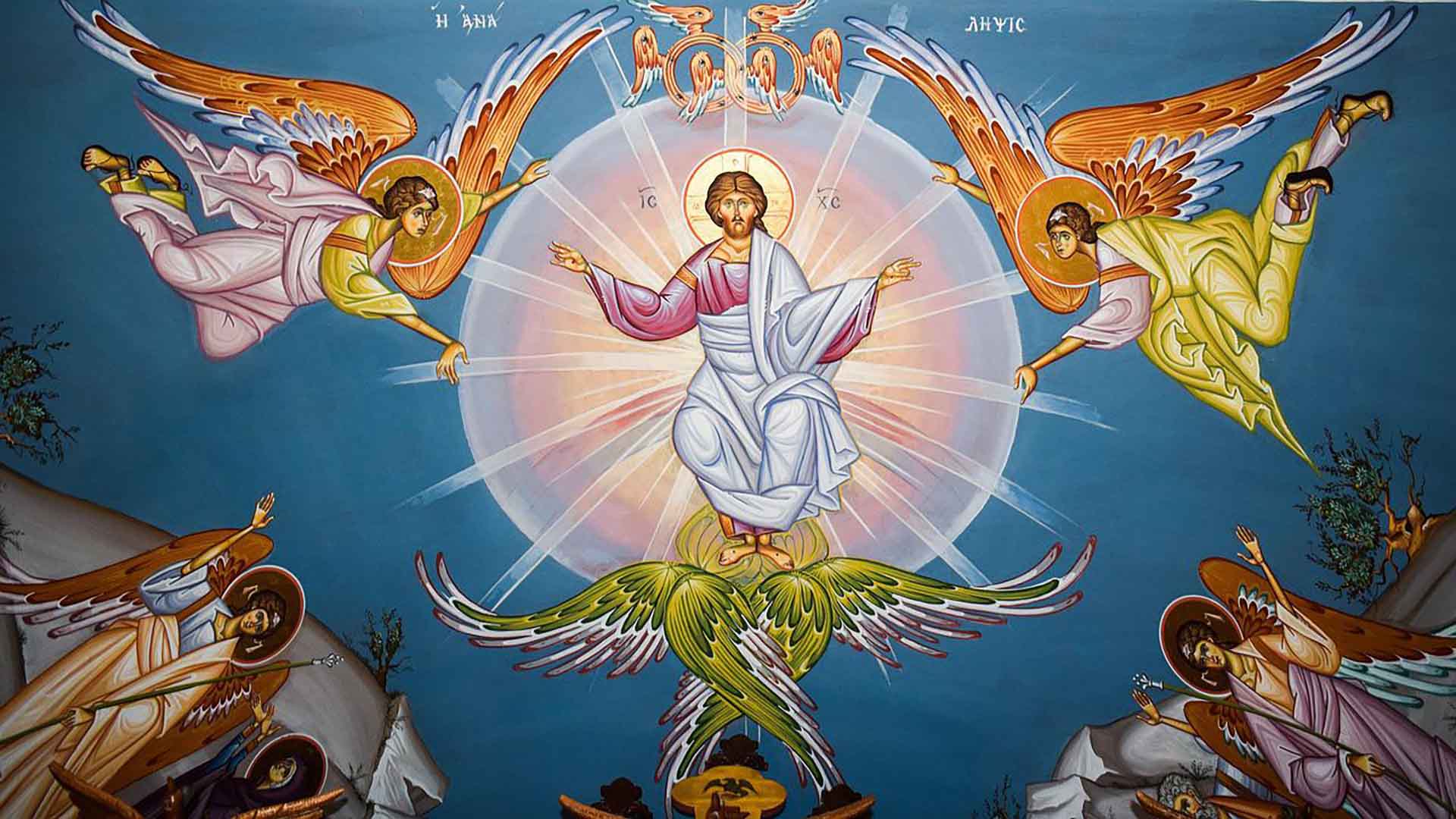

The Promise of Ascension

A solemnity and holy day of obligation like the Ascension rightly arouses the curiosity of every believer. The ascent of Jesus Christ body and soul into Heaven, from Mount Olivet, near Jerusalem, on the fortieth day after Easter, was no mean occurrence. Obviously, the why and how of it are hugely more intriguing than the what and where, and eminently worthy of inquiry.

The life of Jesus was a string of sacred mysteries. The Incarnation was the first and the Ascension, the last of them all. The latter was immediately preceded by and intimately related to the Resurrection. It marked the ultimate exaltation and glorification of Jesus by the Father in Heaven, who, (humanly speaking) seating Him at His right hand, made Him the centre of the world history and controller of all earthly and celestial dominions.

How did the Ascension of Jesus occur? Jesus led his disciples to the Mount, and soon after He had addressed them, raised His hands and blessed them, ‘he was lifted up while they looked on, and a cloud took him from their sight.’ How did the disciples react? They did him homage, returned to Jerusalem with great joy, and stayed in the temple praising God. While Jesus’ A scension was similar to that of Elijah, Jewish tradition also points to the ascension of Abraham, Moses, and Isaiah.

scension was similar to that of Elijah, Jewish tradition also points to the ascension of Abraham, Moses, and Isaiah.

However, who can deny that in our day and age the Ascension seems truly fantastic and begs an explanation! How are we to understand something that defies the laws of gravity? Well, for starters, it was a happening that the eleven disciples witnessed and the Evangelists have recorded. Besides, it is not any more difficult to accept the mystery of the Ascension than that of the Resurrection. After all, it is God who has made the natural laws; He can also tweak them to assert His supremacy and get around His children to acknowledge it.

But that is by no means the only reason why God deemed it fit to realise the Ascension. After Jesus had credibly upheld His claim of rebuilding the ‘Temple’ in three days, He lived amidst His disciples for forty days (important Biblical figure, denoting a new, enlivening period) giving ample proof that the Son of God was alive. However, that he was asked by the disciples, very prosaically indeed, if He had returned to restore the kingdom to Israel was ample proof that the disciples had not understood the Lord’s mission on earth!

Hence, Jesus undertook to re-educate the disciples about the kingdom of God. Would He succeed in doing in forty days what He had failed to accomplish through his three-year ministry? It may be noted that the quarantena only meant an orientation on how to continue the evangelising mission. Jesus gave out laws; prepared the structure for His Mystical Body, the Church; and announced the coming of the Holy Spirit to help His disciples carry out His ongoing mission.

But then, why have the Holy Spirit to do something that, in time, Jesus Himself would have accomplished? That is to say, why did He not extend His tenure on earth? For one, that was not why Jesus had come down to earth -- He had not come to stay, so it was proper that He should return to the Father. Secondly, as Son of Man, he would be subject to the natural laws that governed human life, including aging and death. Finally, and most importantly, by returning to Heaven, Jesus could better guide the Church and His faithful people the world over, through the action of the Holy Spirit. Hence, to grasp and understand the importance of the return of Jesus back to Heaven, Paul prays that the “eyes of our heart be enlightened”.

In short, the Ascension marks both the end of Jesus' earthly tenure and the beginning of His deep involvement with His people on earth. He who had come down with trappings of poverty entered into the world of glory and is closer to us than ever before. What is more, His exaltation and glorification are a promise that we too will be exalted and glorified after we have united ourselves to Jesus’ suffering and shown readiness to be part of God’s plan of Salvation.

Note that the Solemnity of the Ascension falls on Thursday, but it is celebrated on the Sunday closest to that day. The First Reading (Acts 1: 1-11) and the Second Reading (Eph 1: 17-23 or Heb 9: 24-28, 10: 19-23) with psalm and acclamation are common for Years A, B and C. The Gospel for this year (Year C) is Lk 24: 46-53.

Strengthened by the Holy Spirit

With the Ascension and Pentecost round the corner, the role of the Holy Spirit has come into sharp focus. Today’s Gospel (Jn 14; 23-29) reminds us that Jesus at the Last Supper had assured His disciples that they would not be orphaned; He would remain for ever in their midst through the Holy Spirit: ‘The Counsellor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you.’

It is reassuring to have such a Paraclete – Advocate, Helper, Comforter, Intercessor; it is equally heartening that Jesus promises a close relationship with whoever loves Him and keeps His Word. But what does it mean to love Jesus? It means doing the will of His Father. And what is His Father’s will? It comprises all that He has decreed in love and is now found in Church teaching and sacred Tradition.

Amor vincit omnia: love conquers everything. Love is indeed a harbinger of peace – which is priceless when it comes from Jesus! It is a peace ‘not as the world gives’, and so, irreplaceable. The Lord’s peace is not an insurance policy that promises 'peace of mind'; it is rather a state of being that comes about from knowing who we are, why we are here and what is our final destination. It is a peace that comes from having the right priorities: putting God above all people and all things. It is a peace that comes from making God the centre of our lives. One of my favourite hymns says it all: ‘No one can give to me that peace which my Risen Lord, my Risen King, can give.’

It is clear from the First Reading (Acts 15: 1-2, 22-29) that the first Christians depended on the Holy Spirit for guidance, and they practised love and peace. Of course, it was never a smooth ride: despite the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, the community witnessed infighting. But what is marvellous is that they resolved their conflicts in love and peace; through consultation, dialogue, consensus.

Consider that thorny issue of whether or not pagans had to go through the rituals of Judaism (e.g. circumcision for male converts) before they embraced Christianity. Paul and Barnabas consulted the Apostles and elders back in Jerusalem. After they had found a feasible solution, at what came to be called the first council of Jerusalem, they were quick to reach out to their brethren in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia: they did not impose circumcision upon the catechumens of both Jewish and pagan origin, but they encouraged them, with due reason, to abstain from what was sacrificed to idols; from blood and what was strangled; and from unchastity.

Consider that thorny issue of whether or not pagans had to go through the rituals of Judaism (e.g. circumcision for male converts) before they embraced Christianity. Paul and Barnabas consulted the Apostles and elders back in Jerusalem. After they had found a feasible solution, at what came to be called the first council of Jerusalem, they were quick to reach out to their brethren in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia: they did not impose circumcision upon the catechumens of both Jewish and pagan origin, but they encouraged them, with due reason, to abstain from what was sacrificed to idols; from blood and what was strangled; and from unchastity.

It is obvious that the Apostles and the elders exercised great pastoral care. Later, this model of social, emotional and spiritual support became integral to evangelisation of prospective converts and neo-converts the world over (including Goa, way back in the sixteenth century). The Holy Spirit became an instrument of the Lord’s peace: where there was hatred, he sowed love; where there was injury, pardon; where there was doubt, faith; where there was despair, hope; where there was darkness, light; where there was sadness, joy. After all, peace, love and joy are among the many fruits of the Holy Spirit.

Finally, from the Second Reading (Rev 21: 10-14, 22-23) we understand that with Emmanuel (God with us) and the fruits of the Holy Spirit we come close to Heaven, which is the new and eternal Jerusalem. The angel showed St John a holy city perched on a high mountain. There was no temple in the city: ‘its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb’. There was no more sun and moon: the glory of God was its light, the Lamb its lamp. This is where we all belong; our citizenship lies in Heaven. What a privilege!

Who can deny that our Christian identity is a privilege? But, at the same time, privilege entails responsibility – noblesse oblige! Thus, we are called to be temples of the Holy Spirit, the salt of the earth and the light of the world. We are called to pray for peace in our personal lives and in the world. As a spiritual exercise, it would also be a good idea to identify places that are in need of liberation from the scourge of sin and evil; and when we exchange a sign of peace at Mass, dearly wish that the peace of Jesus be always present in our hearts and minds. To crown it all, let us make the eternal city the goal of our earthly pilgrimage, with the Holy Spirit as our Guide.