Don Bosco’s: after a kind of absence

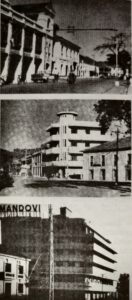

Way back in the 1970s, how did our parents choose from half a dozen schools in Panjim? Don Bosco’s must have been the most obvious choice, given its infrastructure and proven track record; it was a dream school to many from far and wide and all stations in life.

Don Bosco’s had by far the largest educational campus in the then union territory of Goa. The main, (then) two-storeyed edifice, spacious, bright and airy, housed the school, the priests’ residence and the boys’ boarding (especially during the Persian Gulf boom). The building was cut across by a passage leading to a new shrine dedicated to Our Lady of Fatima, where Mass for the students, on First Fridays, was a spiritual feast. Elsewhere on the campus, sports facilities were among the best at the time. And to wrap it all up, the school motto, Virtus et Scientia, pointed to a holistic education and recipe for happiness.

But what man is happy? Only "he who has a healthy body, a resourceful mind and a docile nature," says a philosopher. To our good fortune, that was quite the staple diet we students grew up on; it let Bosco boys stand out not only in academics, but also in intra- and extra-mural pursuits that included music (remember the brass band?); sports (particularly football, basketball and hockey); elocution, debate, and so on. ‘All-rounder’ was a buzzword, in the run-up to the examination of life.

Needless to say, school was no cakewalk; sometimes there was waywardness, dejection and frustration along the way. But, through it all, the aspirations of the Salesian brotherhood shone bright, distilled into that martial anthem whose lyrics and melody render me nostalgic before they finally pep me up:

We the proud Don Bosco boys

brave Don Bosco brotherhood.

Nursing in our heart the joys

Of true knowledge and the good.

Forward march with equal pace

Through our country’s sounding ways

Treading where our fathers trod

In the glorious light of God.

We who are the happy band

Will not shrink from sweat and strife.

In the service of our land

For a brighter cleaner life.

We will toil till out of gloom

Day shall dawn and deserts bloom.

And our country’s blessed soil

Shall be green and gold for God.

Don Bosco’s was clearly ahead of its time. It had a vibrant ‘Past Pupils Association’. When alumni found it tough to secure proper lodgings in the bustling capital, a hostel was built for the purpose, at a far end of the campus. So much for connectedness. But perhaps even more distinctive was the Oratory, an institution inspired by the founder St John Bosco himself. The Saint of Turin had realised, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, that young minds longed for more than just hard skills – they sought loving kindness!

For long, the Oratory functioned in the desacralized, old Fatima chapel located right in the middle of the vast estate; inscribed on its façade were the words ‘Visitasti Nos’ (You Visited Us, in Italian) commemorating the coming of the Pilgrim Virgin statue there in 1950. The place was a safe haven to a motley crowd that included the less fortunate, poor, and abandoned youth. And even those who did not much fancy the place did feel its magnetic pull at some time or other in their lives!

All things considered, it was a matter of pride to belong to a school where one trained in good citizenship of the church, the country and the world. Catechism and Moral Science classes virtually set the tone. And who can ever forget ‘Don Bosco’s Seven Tips to Boys’ bulleted in the school handbook? They always bear repeating:

- Do not waste time.

- Do not offend God.

- Do not overeat before studying.

- Avoid bad companions as poisonous snakes.

- Choose some studious boys as friends.

- When it’s time to play, get in there and play.

- Do not daydream! Keep your mind on your books when studying.

- Above all, PRAY.

Hopefully, a lot of that wisdom has stayed with the “proud Don Bosco boys” and been passed on to generation-next!

Oh, how all of this seems far back, yet close at hand!... Am I lost in reverie? Be that as it may, our alma mater has her feet firm on the ground; even if at times we have taken her for granted, she, like a doting mother, has been there for us. And whereas her alumni have grown old, she has, thankfully, only grown big! Here I wish to pay homage to my teachers, some of them priests and brothers; and to remember my classmates too: we are now a scattered lot, aren’t we? No wonder it feels like a kind of absence….

On the occasion of the triple Jubilee, I salute the Salesian family for holding on. Don Bosco’s has grown into a splendid oasis amidst a slowly emerging concrete jungle; but then again, weeds of the world must not be allowed to close in on it! Don Bosco’s has come a long way, and the Founder’s spirit must live on: this will be a clincher for twenty-first century parents waiting to choose from more than half a dozen schools in the city!

(First published in the Souvenir Back to School)

(Banner: https://sdbpanjim.org/newsdetails.php?id=1505; Pics 2 and 3, courtesy Eustaquio Santimano, Flicker)

Panjim Church to me

In reply to a quick question from Dolcy D'Cruz of Herald, Panjim, last night... Thank you, Dolcy!

The city church has been part and parcel of my life for as long as I can remember. It is an architectural gem, perhaps best remembered for its iconic zigzag stairway.

However, my relationship with my parish church was on another plane. On Sundays, my family and I were regulars at the Mass held in Portuguese. It is also there that we attended Easter and Christmas services.

Come December, we awaited the Feast of the Patroness with great anticipation. It provided an excellent spiritual preparation for Christmas, for the angelic music of the Salves at twilight heralded the celestial choirs singing "Gloria in Excelsis Deo" a fortnight later. The church was thus my spiritual powerhouse. I still feel a strong pull even though I no longer live in the city centre.

On the other hand, I feel sorry to see the church helplessly serve as a backdrop for cultural events and photoshoots. There is scant respect shown to the sacred nature of the church complex. You find tourists dressed inappropriately, lingering on the stairway or ambling into the church premises. Who is going to stop this menace?

Memories of Panjim

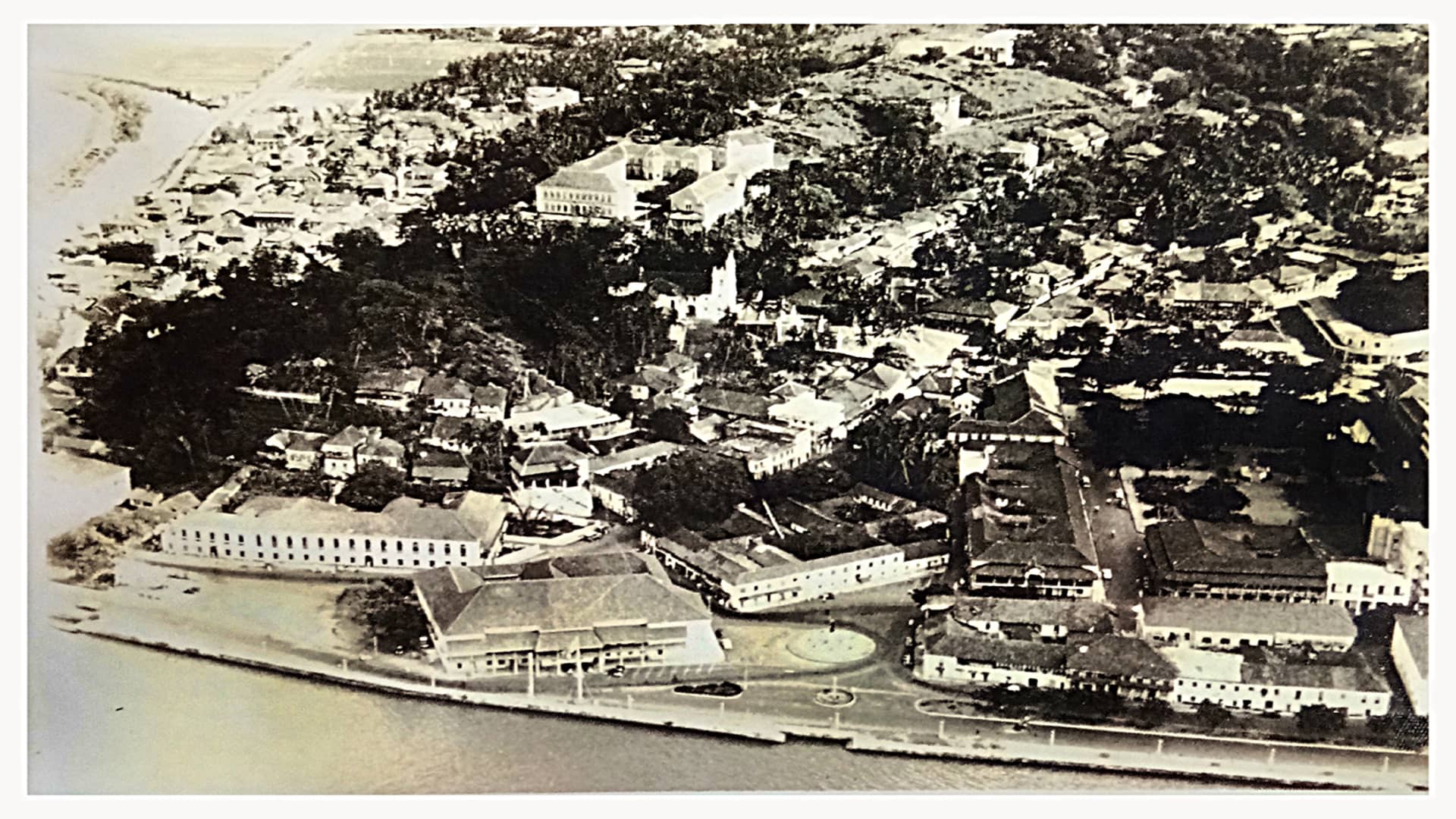

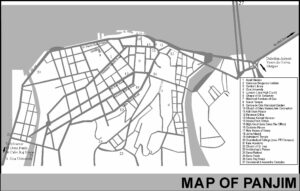

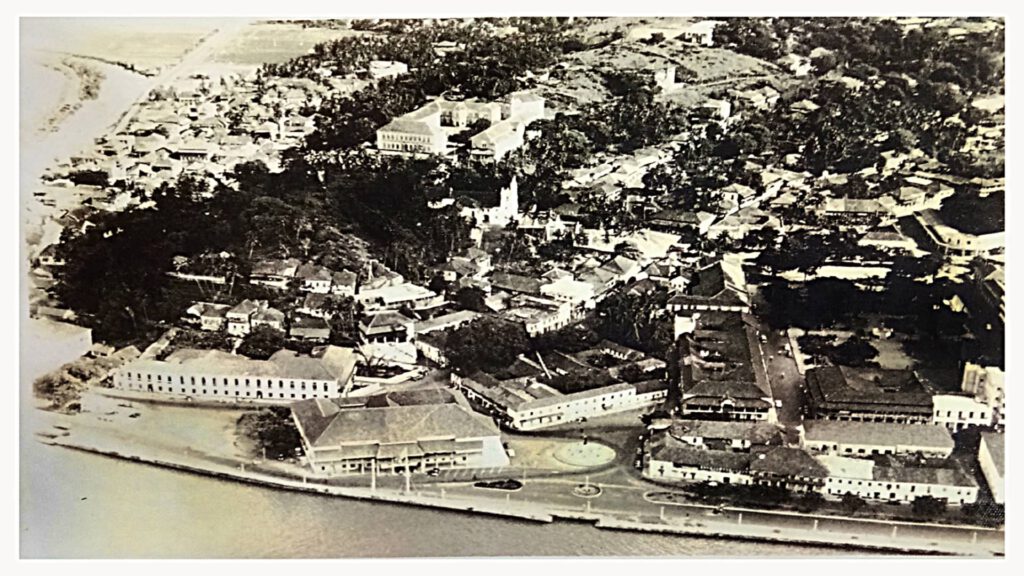

In the 1960s and 1970s, Panjim was the picture of calm and sweetness, of simplicity and decorum. The city stretched from Ourém Road up to the Military Hospital in the east-west direction and from the riverine avenue up to Altinho and Batulém in the north-south line. As a garden city on the water’s edge, its rhythm paced by the gentle Mandovi, Panjim had an identity and a charm all its own.

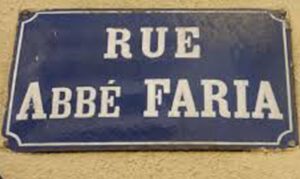

When I was a child, I lived in the heart of Panjim, next door to the centuries-old Adil Shah Palace and under the hypnotic gaze of Abade Faria. My day dawned with the chirping of birds, soon to be followed by the loud siren of the Bombay steamer docking at the Customs pier. The hustle and bustle of the passengers, the clatter of the baggage handlers and the taxis honking on Vasco da Gama Avenue (now Dayanand Bandodkar/DB Marg) roused the 40,000 residents of Panjim still wrapped in sleep, reminding them of their morning tasks, especially of school.

It was now as if the frenzy of the Indian metropolis had disembarked in the Goan capital! The din quickly drifted to the main arteries, Dom João de Castro Avenue and Afonso de Albuquerque Street (now Mahatma Gandhi Road/MG Road), where the bureaucracy and business establishments were situated. Upon the departure of that steamer midmorning, the city regained her composure; she lunched and enjoyed her siesta, and by 4 o'clock resumed her daily battle, which ended around 8 in the evening.

Panjim enjoyed an organic lifestyle only a wee bit different from that of the countryside! Hot bread and fresh fish went door to door; and at the municipal market they sold local produce from villages nearby. But it wasn’t only about what the people bought; it was equally about what they thought – about how they treated one another and the surroundings. They displayed civic sense and were a God-fearing lot. That church, mosque and temple were practically on the same street spoke volumes of communal peace and harmony in the city.

A Japanese writer once labelled Panjim the ‘most unIndian of all Indian cities.’ In his mind’s eye he probably saw an urban landscape devoid of skyscrapers, filth, and chaos. But had he perhaps noted the spiritual architecture of the citizenry? Panjimites were not caught up in a rat race; they lived modestly and contentedly, fearing none, much less the police, a ramshackle force anyway! Burglary was rare, and murder or suicide almost unheard of. Conscience and benevolence – or better, munisponn (humanity, in Konkani) – reigned. In the words of a fado (Portuguese folk song): ‘If someone humbly knocked at our door, they would sit with us at table; and even in the poor comfort of our home, we had loads of affection to offer.’ In short, the townsman didn’t need much to brighten his existence.

Panjim was all things to all people: a nature lover’s dream, a pedestrian’s delight, a balm for a troubled mind. There were open spaces and colonnaded footpaths. Traffic was simple and light – motorcycles, bicycles, even bullock carts, and automobiles ranging from the popular Volkswagen to the luxurious Cadillac. These were the last of the Mohicans that had emerged, quite paradoxically, from the Economic Blockade; in a way, they denoted the Goan cosmopolitanism.

Panjim was all things to all people: a nature lover’s dream, a pedestrian’s delight, a balm for a troubled mind. There were open spaces and colonnaded footpaths. Traffic was simple and light – motorcycles, bicycles, even bullock carts, and automobiles ranging from the popular Volkswagen to the luxurious Cadillac. These were the last of the Mohicans that had emerged, quite paradoxically, from the Economic Blockade; in a way, they denoted the Goan cosmopolitanism.

Panjim was unique; it prided itself on single items: on one daily in Portuguese (O Heraldo) and in English (The Navhind Times); on a radio station (All India Radio) and a music academy (Academia de Música) which had nowhere to hold its annual concert other than at the only public hall (Institute Menezes Bragança). Likewise, Panjim was proud of its one and only three-star hotel (the Mandovi), of its ice-cream shop (Eskimo), and its South Indian restaurant (Shanbhag). Just one cine-theatre (Nacional), one bookstore (Singbal), and one public library (Central) catered to its citizens. For their healthcare needs, they went to the medical college hospital (Escola Médica). Panjim’s children depended on one public ground and football stadium (at Campal) and its adults on their Hyde Park (Azad Maidan) to go to yell their guts out. And children and adults alike enjoyed the evening breeze at the municipal garden (Garcia de Orta).

The quiet beauty of that public garden, the city’s oldest and largest, is etched on my memory: as kids, we jumped there with excitement while our elders bantered back and forth, comfortably seated on self-appointed, gender-segregated benches. From the bandstand, where the navy orchestra and others performed occasionally, I remember naively shouting slogans (“Tujem mot konnank? – Don Panank!”) in the runup to the Opinion Poll in 1967! There were cafés and bars, taverns and little gaming houses thereabouts; and some distressing sounds of tu-tu-main-main at a nearby newspaper office always wafted into the garden. None of this must have ever solved the city’s problems of scarcity and costliness, of poverty and drunkenness! The latter two could be starkly seen in a fringe area dubbed Tambddi Mati (Red Earth), thanks to its untarred alleys and the little red lights on its porches.

Panjim, therefore, was no garden of virtues. Its relative insularity had prompted me to leave for a city abroad – I was peeved about being everybody's business – until I changed my mind fearing that, meanwhile, my city would become another Mumbai – like nobody’s business! At any rate, the city had already started to expand westward into Miramar and Dona Paula while apartment blocks were quietly replacing houses in the city centre. There was a bridge on the Mandovi and a bus stand in the middle of the Pattó marsh; on the other hand, the sewer network lay incomplete, power outages were common, and piped water was restricted. Pure air was no doubt a saving grace; but then again, in the rains, Panjim would suddenly become Venice!

Panjim was petite, yet many of its sites stayed put on my bucket list. The stairways to Alto dos Pilotos and Escadinhas de Pedras Soltas resembled picture-postcard Lisbon – except for their state of disrepair. The likes of Saraswati Mandir, a library from the post-Republican days, were dimly lit and crowded. And while Tribunal da Relação (High Court) was a charming building adjacent to my house, I never visited it, petrified as I was by the magistrates’ stern faces. In much the same way, I was awed by the Arquivo Histórico (State Archives), but its documents half a millennium old were an ocean that my little bucket could not hold.

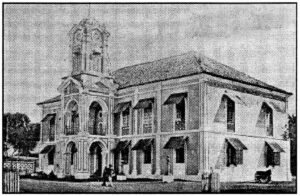

Who can ever forget the five-block Lyceum complex at Alto de Guimarães? Seniors told me that it was once reminiscent of the millennial Portuguese university town of Coimbra; but alas, the spirit had moved – only the shell remained. Worse was the fate of the Senado de Goa (municipal chamber), a distinctive building with a clock tower and hemmed in by gardens; it was torn down on flimsy grounds, so all that one can see now is a gaping space. What’s worse, the city never again got a town hall to match. These and some other facets were thus beyond my little self.

Even so, I eventually came to love and identify myself with the city. People of different creeds lived here in mutual respect. And as though time and tide waited for ever, they happily stopped in their tracks to exchange pleasantries – not to forget that men took off their hats to ladies without ado! Time was when baptisms, birthdays, and funerals were major events; and in those pre-television days, a stroll on Miramar beach at sunset, or a ride to Campal on goddia-gaddi (horse carriage) was all it took to dispel the ennui.

The rest of the magic was left to the cultural calendar to pull off. The Carnival parade, the street dances at clubs Nacional and Vasco da Gama, and the annual quermesse (open-air fair) at Fontaínhas were eagerly awaited. The Way of the Cross wending its way from the iconic Church of the Immaculate Conception up to Paço Patriarcal (Archbishop’s Palace) at Lent; the candle procession streaming the other way around, in October; Christmas celebrations et al were sights to behold. Holi, Ganesh and Diwali brought in traditional delicacies from Hindu friends. And all of this contributed towards a sweet spirit and the joy of living in Panjim.

Forty years on, Panjim is an entertainment hub – one big casino, garish, noisy and manic – which the Covid-19 virus briefly disrupted as only Covid can. The ensuing lull, however, helped me uncover the face of my city. I began to feel a homesickness for that time in the past when we faced shortages of sorts while the world seemed to be enjoying abundant life. Today, this newfound calm and sweetness, simplicity, and decorum make me feel we were never short of anything. No wonder Panjim was the apple of the eye of every Goan worth his salt!

(First published in The Peacock Quarterly, Panjim, July 2022. Reprinted by The Goan Review, Jan-June 2023 https://online.fliphtml5.com/cmlao/eron/?1681654486031

Notes

Abade Faria, or Abbé Faria, refers to the Goan priest José Custódio de Faria (1756-1819) celebrated as ‘Father of Hypnotism’. A statue depicting him in the act of hypnotising a lady was erected in 1956.

Academia de Música (1952), now Kala Academy, was the first professional music academy in Goa, set up under the baton of Europe-trained maestro António de Figueiredo.

Adil Shah Palace was the official residence of the Portuguese viceroy/governor-general (1759-1918). It continued as the seat of government and housed the legislature (pre- and post-1961). An apt extension was built in 1970. The palace is now a museum.

Alto dos Pilotos and Escadinhas de Pedras Soltas (literally, ‘Pilots’ Height’ and ‘Loose Stone Stairs’, respectively) are two of Panjim’s many stairways. The former is located behind Fazenda (Revenue Office) building and the latter in Fontaínhas/Mala ward.

Arquivo Histórico (1595) was first curated by Diogo do Couto, co-author of Décadas, an official history of the Portuguese in Asia and Africa.

Azad Maidan, formerly Praça Afonso de Albuquerque, had a monument to the Portuguese conqueror; now rededicated to Tristão Bragança Cunha, the ‘Father of Goan Nationalism’. A Martyrs’ Memorial was added in the 1970s.

Bombay steamer was a coastal service between Goa and Bombay. Several companies ran it for a century beginning from the last quarter of the 19th century.

Campal, meaning ‘a clearing’, is the area originally developed by viceroy Dom Manuel de Portugal e Castro (1827-1835).

Central Library began as Pública Livraria (1832) and was attached to Instituto Vasco da Gama (1925-1959). Renamed Central Library in post-1961 Goa, it is now housed in a state-of-the-art building at Patto Plaza.

Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception is an iconic structure overlooking the city.

Clubs Nacional and Vasco da Gama were established in the early 20th century, the former largely sponsored by natives and the latter by Panjim-based continental Portuguese.

Economic Blockade (1954-56) imposed by the Indian Union prompted then Portuguese Goa to accelerate agricultural development, import of goods (including automobiles), and start direct flights (Goa-Lisbon-Goa, via Karachi).

Escola Médica, short for Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa (1842), was Asia’s first medical school. Located at the Palace of the Maquinezes, it added a hospital building in 1927, now the headquarters of Entertainment Society of Goa (ESG). It was renamed Goa Medical College in the 1960s and shifted to Rajiv Gandhi Medical Complex, Bambolim, in the 1990s.

Garcia de Orta Garden is named after the Portuguese Jewish botanist and author of the seminal Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas da Índia (1563). He owned an estate in the old Goan capital and had the island of Mumbai on lease from the king of Portugal.

Menezes Bragança Institute, formerly Instituto Vasco da Gama (1871-1963), is regarded as one of Goa’s finest cultural institutions.

O Heraldo, founded by Messias Gomes, in 1900, was the first daily published from the Portuguese colonies; now Herald, published almost exclusively in English, since 1983.

Opinion Poll, the first of its kind in India, was held to ascertain the wishes of the then Union Territory of Goa on the proposed merger with Maharashtra. The popular, anti-merger slogan meant: ‘Your vote?’ – ‘For Two Leaves, for sure!’

Paço Patriarcal, or Patriarchal Palace, is the official residence of the Archbishop of Goa and Daman, who holds the title ‘Patriarch of the East Indies’.

Saraswati Mandir, on 18th June Road, is one of the many libraries set up by Hindu trusts in the new era of political and religious freedom under the Portuguese Republic (1910).

Senado de Goa (1511) was set up on the lines of the municipal senate of Lisbon.

The Navhind Times, founded in 1962 by mining magnate Vasantrao Dempo, is the first English-language daily to be published from Goa.

Tribunal da Relação (1544), had jurisdiction over the Portuguese Eastern Empire (Africa to Japan). It was downgraded to a Judicial Commissioner’s Court under the Indian Union and became a Bench of the Bombay High Court in 1982.

Pangim da minha infância

Nas décadas de 60 e 70 do século XX, a cidade de Pangim era a imagem da calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro. Estendia-se da Rua de Ourém ao Hospital Militar (na direcção leste-oeste) e da avenida marginal ao Altinho e Batulém (na linha norte-sul). Como jardim à beira-mar plantado, a quem o suave Mandovi pautava o ritmo da vida, Pangim tinha uma identidade própria e um encanto muito seu.

Vivia eu no coração de Pangim, ao pé do antigo Palácio do Idalcão e sob o olhar hipnótico do Abade Faria. Raiava o nosso dia com o chilrear dos pássaros, seguido da sonora sereia do barco de Bombaim a atracar no cais da Alfândega. A essa hora, o vaivém apressado da multidão, a algazarra dos bagageiros e a buzina dos táxis na Avenida Vasco da Gama (hoje D. B. Marg) eram um chamariz para uma boa parte dos 40.000 pangimnenses ainda envoltos em sono; um impulso matinal para as suas tarefas, sobretudo a escolar.

Era como se o frenesi da metrópole indiana tivesse acabado de desembarcar na capital goesa! Essa onda pressurosa propagava-se um pouco por toda a parte, a começar pela Avenida Dom João de Castro e a Rua Afonso de Albuquerque (ora M. G. Road), as principais artérias, dominadas pela burocracia e pelo comércio. Com a partida daquele barco, no meio da manhã, a cidade voltava à calmaria; almoçava e dormia a sesta, e pelas 4,00 horas retomava a batalha quotidiana que só terminava por volta das 8,00 da noite.

Uma vivência orgânica, não muito diferente da do campo! À devida hora vinha à porta o pão e o peixe fresco; iam às compras os empregados domésticos, que se prezavam de ser íntegros, temendo não tanto a polícia como a Deus! O trânsito era ligeiro – motocicletas, bicicletas, até carroças, e automóveis, do popular Volkswagen ao luxuoso Cadillac. Estes eram os últimos abencerragens da bonança que resultara, paradoxalmente, do Bloqueio Económico de 1955, e ora simbolizavam o nosso cosmopolitismo.

Disse um escritor japonês que Pangim era a “most unIndian of all Indian cities.” Referia-se certamente à tradicional arquitectura indo-portuguesa, desprovida de arranha-céus e da imundície e do caos que caracterizavam os centros urbanos do subcontinente. Mas teria ele dado conta da arquitectura espiritual do povo? Este não era de grandes ambições e vivia numa mediania. O roubo era raro, e raríssimo o homicídio ou o suicídio. Não havia indícios de sectarismo ou de violência, pois reinava a consciência e a benevolência, ou aquilo a que chamamos munisponn: se à porta humildemente batesse alguém, sentava-se à mesa com a gente – como canta o fado; e no conforto pobrezinho do lar havia fartura de carinho, e bastava pouco para alegrar a existência do citadino.

Pois é, a cidadezinha daquela época tinha um só diário em português (O Heraldo) e em inglês (The Navhind Times); uma só emissora (a All India Radio); um só salão (o do Instituto Menezes Bragança), onde actuava a única academia de música; um único hotel de categoria (o histórico Mandovi); uma só loja de gelados (o Esquimó); um só restaurante sul-indiano (o Shanbhag); um único hospital geral (o da Escola Médica); um único cine-teatro (o Nacional); uma só livraria (a Singbal); uma única biblioteca de fôlego (a Central); uma só grande praça pública (o Azad Maidan); um só campo de jogos público (no Campal); um só amplo jardim (o Garcia de Orta), onde, à tarde, convergiam crianças e adultos, ficando aqueles a saltitar pelos canteiros e estes a conversar amenamente num canto.

Desse jardim guardo várias memórias: a da música executada no seu artístico coreto e a dos slogans – “Tujem mot konnank? – Don panank!” – que eu ingenuamente gritava, nas vésperas do Opinion Poll, em 1967. Lembro-me dos cafés e bares em redor e do jornal em cuja Redacção se ouvia um aflitivo dize-tu-direi-eu, nem por isso resolvendo os problemas da carestia e escassez, da pobreza e embriaguez, estas comuns, por sinal, no bairro pitorescamente denominado Tambddi Mati (Terra Vermelha), tanto por falta de asfalto nas ruelas como pelas lampadazinhas vermelhas nos alpendres!

Enfim, Pangim não era nenhum jardim de virtudes. Até pensara em mudar de cidade, por não suportar a insularidade e me sentir everybody’s business; mas em vez disso mudei de ideia, por recear que entretanto a cidade da minha infância se transformasse num pequeno Bombaim, e nós, em nobody’s business! Mas não havia remédio; a cidade estava já em franca expansão: as casas cediam o lugar a blocos de apartamentos; era construída uma ponte sobre o Mandovi e uma praça de automóveis no pântano do Pattó. Por outro lado, estava incompleta a rede de esgotos; havia falhas na electricidade, e era racionada a água canalizada. O ar era puro; mas ai que, na monção, Pangim de repente era Veneza!...

Ora, fui aprendendo a amar a cidade e a gente. Éramos poucos, éramos irmãos – e saudáveis as relações entre os vizinhos, independentemente dos seus credos. Naqueles tempos, os cavalheiros tiravam o chapéu às senhoras e paravam para dois dedos de conversa! Os baptizados, aniversários e funerais eram eventos de vulto. Não havia televisão; para dissolver o tédio bastava um passeio pela praia do Miramar ou de goddia-gaddi até ao Campal, ao pôr-do-sol. O arraial nas Fontaínhas, o desfile do Carnaval e os bailes nos clubes Nacional e Vasco da Gama vinham a seu tempo. Dir-se-ia o mesmo da Via Sacra; da procissão das velas que do Paço Patriarcal descia até ao ex-libris da igreja matriz; e das novenas e festas religiosas. De tudo isso nascia o espírito de família e a alegria de viver em Pangim.

No afrouxar forçado dos meses da covid-19, voltei a descobrir o rosto da minha cidade. Se em tempos nos faltavam coisas que os outros tinham em abundância, hoje, sentindo novamente aquela calma e doçura, simplicidade e decoro, vejo que nos não faltara nada…. Não admira, pois, que Pangim tivesse sido sempre a menina dos olhos de todos os que se prezavam de ser goeses!

Foto de Pangim, gentilmente cedida por Willy Goes

Publicado na secção portuguesa do magazine dominical do diário Herald

First televised Mass fulfilling Sunday obligation

'How was your Mass on the fourth Sunday of Lent, 22 March 2020?' That's what my journalist friend Melvyn Mesquita of The Goan wanted to know. Here's what I said him about my experience of participating in a live streamed Mass yesterday....

“It is interesting how a family, which is regarded as a ‘domestic church’, truly became a church where we participated in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass as one family.

“We made it a point to tune in to Rádio Televisão Portuguesa Internacional (RTP-i), the Portuguese channel, which our eldest son Fernando, who is home-bound, tunes in to every Sunday. He was particularly happy that we sat by his side throughout the Mass, televised from the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament of the church of Christ the King, Portela, near Lisbon.

“No doubt we missed Holy Communion under the species of the consecrated host but made up by way of Spiritual Communion. All in all, we enjoyed the fruits of digital technology very meaningfully, in that our domestic church felt really universal.” (The Goan, 23 March 2020)

For one, it felt quite odd to be attending Sunday Mass at home. Then, it was sad to see only a handful of people holding it for us in loco: the main celebrant, Mgr. Joaquim Mendes, auxiliary Bishop of Lisbon, two concelebrants, three readers and three gent choir members. The Bishop preached to an empty church, yet it was gratifying to see his message going across the globe.

Way back in the year 1940, Mgr. Fulton Sheen was one of the first priests whose Mass was televised. It was telecast by the experimental W2XBS, a CBS affiliated TV station. During the sermon, Sheen is known to have remarked, "This is the first religious television in the history of the world. Let therefore its first message be a tribute of thanks to God for giving the minds of our day the inspiration to unravel the secrets of the universe."

Some two decades ago I had a vicarious experience of a televised Mass, through a senior citizen in the Goan village of Benaulim. He would be seated, all suited and booted, before the TV, eager to fulfil his Sunday obligation in the comfort of his home, thanks to RTPi. Back then, his Sunday habit had evoked peals of laughter amid family and friends. It was only much later that I realized the idiot box legitimately fulfilled an earnest desire.

Eventually, the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN) entered our home. More recently, some Christian channels started locally, and finally the Catholic Charismatic Renewal Television (CCRTV), modelled largely on EWTN, made its presence felt in Goa in December 2017. But it was only much later that I came to appreciate its benefits for the home-bound.

For example, our son Fernando, is a Sunday TV Mass goer. He waits to meet the Lord via television, whether or not a Eucharistic minister from Stella Maris chapel has administered him Holy Communion that morning. He has a touchingly respectful posture, which he sometimes finds difficult to adopt when he is at Mass amid a large congregation in a chapel or church. Something here disturbs him; but at home, left to himself or in company, he doesn't show any signs of irritation.

On the fourth Sunday of Lent this year, we prepared a table with an appropriate cover, placed a candle and a crucifix on it. We gathered as a family, appropriately dressed, and recited the prayers and responses, reflected on the readings and joined in singing the hymns. No electronic device other than the TV set was on, and no chores allowed. We focused on the Holy Eucharist, immersed ourselves in the presence of God and received Spiritual Communion. All that was in keeping with some guidelines for attending online Mass which I'd read and disseminated on social media the previous day.

Fulton Sheen was right. The daily message on several religious television stations in the world today is indeed "a tribute of thanks to God for giving the minds of our day the inspiration to unravel the secrets of the universe." Televised Mass fulfilling Sunday obligation and weekday Masses for habitués have come to stay after the first one on 23 March 2020. It is equally important, however, that regular church services begin at the earliest in God's own House, for lovely is the dwelling place of the Lord Almighty!

A Life in Translation

Quasi-Memoir-1

I was clueless as to 30 September, International Translation Day, instituted two years ago. I got the lowdown from that enterprising, Herald journalist Dolcy D’Cruz: for the purpose of a feature to mark the occasion, she'd sought to know what translation meant to me and how I went about my activity.

‘Translation is a magical thing,’ I said to her, almost instinctively. ‘Not only does it help spread information and speed up business across the globe, it promotes cultural understanding.’

At the back of my mind were Tolstoy and Dostoevksy, Verne and Dumas, Anderson and Grimm, authors whose native languages I didn’t know. And I shed a tear for those who had to depend on renderings of Shakespeare, Dickens and Twain, and why not, Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie and P. G. Wodehouse. I was lucky to read them all in the original, as I was, when it came to my father’s recommendation of a Portuguese staple diet: Júlio Dinis, Garrett, Camilo, Eça, Ramalho, Aquilino, for a novice; and my additions: Pessoa, Torga, Namora, Agustina, Lobo Antunes, and Saramago (with a pinch of salt).

Literary translations have made the world richer. And it’s not literature alone that has depended on translations; even the most disparate subjects like history, medicine and everything in between have benefited from them. If in the early twentieth century, seminarians in our archdiocese had to depend on Latin texts, it wasn’t only because that’s the official language of the Church; there were no translations available in the vernacular!

Even more picturesque was my doctor aunt’s story about the use of French manuals at the Goa medical school, as late as the 1950s: students had soon cultivated the art of reading them aloud in twos or threes, and straight in Portuguese. That was magic!

Early days

As aural memories came gushing, I began to realize that translation had indeed been an organic part of my life. As a child juggling several languages, from Portuguese and Konkani at home, to English, French and Hindi at school, oral translations happened almost as a matter of course. I would reproduce in Portuguese information that I’d received in English, and vice-versa. Mixing of lingos and literal translations were a big no-no, whereas idiomatic language was warmly encouraged.

Yet, translation per se was never the main concern; the accent was on reading good literature and relishing good conversation; it was about having a dictionary at hand and looking up the meaning of an unfamiliar word; it was about finding le mot juste. It was no cakewalk but, looking back, the long walk was so worth it. And a job well accomplished always translated into joy.

After my father’s remark, ‘Languages are an asset; master them while you’re young,’ the next best thing that stuck in my head was Bacon’s famous quote: ‘Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.’ This was like a command from on high. Or for that matter, F. J. Sheed’s dictum that ‘… minds feed on minds, you cannot nourish your mind with a chop,’ struck me as very sensible.

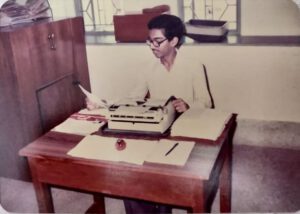

After handling English texts, ‘ex officio’, on school days, I would spend bits of late Sunday mornings decoding Portuguese texts under my father’s tutelage. By the end of high school, I had begun devoting an hour or so to transcribing All India Radio afternoon news bulletins for O Heraldo. And why? Now it just seems so funny: I’d found this arrangement vital since Goa’s first daily, which was on its last legs, no longer subscribed to news agencies and was starving for news. I also thought it would reassure my father who, after retiring prematurely, lent a hand at the paper – for the love of the Portuguese language and practically for free.

In the public domain

That happened to be my first stint with translation outside the domestic sphere. I didn’t think any good would come out of all that. But, three years later (1983), when I least expected it – I was in the first year of college – the then Jesuit priest Teotonio R. de Souza invited me to work as a research assistant at the newly established Xavier Centre of Historical Research of which he was the director. My task was to create summaries in English of the Mhamai Kamat papers written in Portuguese and French. I was also pleasantly surprised that he’d entrusted me two of his research papers for translation. That we argued playfully about his views is quite another matter entirely!

After my MA at the University of Bombay (1985-87) and a language and culture course at the Universidade de Lisboa (1988), I had a short stint as a lecturer in Portuguese at Dhempe College, Panjim, chiefly, to replace my father who was down with malaria. After a few months, I hesitantly took up an interpreter’s job at the Embassy of Brazil, lured by the national capital. On arriving there, however, I was stunned to see that I would be assisting an eighty year old: Pylades Prata Tibery, a Brazilian national of Greek and Italian ancestry, introduced himself as a ‘juiz de gado’ (cattle judge).

Tibery and I crisscrossed the subcontinent, by road and rail, trailing the Nellore buffalo – a breed that, according to the garrulous old man, Brazil had imported from India in the early twentieth century. Our activity was interspersed with a generous exchange of notes on European and Brazilian Portuguese. While the English of his school days was amusing, even more so were his colourful descriptions of ‘convivial society’ expressed in his native Brazilian.

Well, I could hardly be buffaloed by a more outlandish task even if handsomely paid, as indeed I was. It marked the beginning and the end of my honeymoon with translation/interpretation as a full-time job... On my return to Goa, I took up teaching as a career. After the initial hiccups, I found fulfilment in interpreting my students’ thoughts and feelings, and translating their ignorance into knowledge, their anxieties into hope, and their ambitions into reality! Translating and interpreting could now only be side gigs, mostly to oblige friends and family. For instance, I liaised at a couple of wine festivals and carried out humdrum legal translations, among other things. Even these I could no longer endure when I finally had my eyes set on translating literary, historical and spiritual texts. That would surely be a balm to my spirits.

Literary translation

Sometime in 1995, a brief encounter with Editor Arun Sinha of The Navhind Times provided that go. Keen on setting up a literary page to step up his paper’s Sunday magazine, ‘Panorama’, he suggested I work on Goan short stories written in Portuguese. I did produce quite a few translations, but alas, inevitable changes on the home front constrained me to discontinue the series.

But in spite of everything, mine has continued to be a life in translation, of which the Herald article gives a glimpse (see the link below).

(To be continued)

When I met Abade Faria...

I lived next door to Abade Faria for thirty years. As a child, I remember asking my father what that name meant. Keen on passing on informatio n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

Abade Faria is that very striking statue in the heart of Panjim. I couldn’t have met the man himself: José Custódio de Faria was born in 1756, at his mother’s house in Candolim. His father was from a less known village, Colvale. As I came of age, I learnt that he was the son of a priest and a nun… Hold on! They were ‘normal’ people, Caetano Vitorino de Faria and Rosa Maria de Souza, who got married, had a child, and then broke up. The father took holy orders at the then Chorão seminary while the mother joined St Monica, Asia’s largest nunnery, at Old Goa.

The father-son duo then travelled to Lisbon, and onward to Rome, where Faria Jr. was ordained a priest and the father-son duo did their doctorates in theology. On their return to Lisbon, the father was left harbouring nativist ideas; the son, seeking a safe harbour, proceeded to France, in 1788.

That’s how the name ‘Abbé Faria’ makes sense. The French word for ‘priest’ is still in vogue in the English-speaking w orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

In 1988, as I arrived in France, Faria’s poignant story raced through my mind like a film. It was exactly two centuries since the only Goan who participated in the Revolution had stepped into Paris. Alas, I found no trace of his addresses in that magnificent global city. So I was hopeful about seeing the Abbé next in the luminous port city of Marseilles. My joy knew no bounds when I finally sighted a street named after him.

There I was quizzing a few pedestrians on that sleepy thoroughfare. When the very first speaker confessed his ignorance, I was crestf allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’

allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’ s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

My third and final encounter was most memorable. When I fired my standard question – ‘Who is this Abbé Faria?’ – the man playfully shot back at me, saying, ‘He was an Indian – like you!’ And with a smile playing on his lips, he vanished into thin air, while I was stuck in a hypnotic state!

Back in Goa, my interest in Faria redoubled. One fine afternoon, very significantly, the fourth of July, my fiancée came along to see my friend Abade Faria in Colvale. Just locating his family estate in that northernmost village of Bardez took us longer than getting there all the way from Panjim. It felt as though we were searching for something in pitch darkness, no flashlights in hand, when really it was broad daylight… What an exploration indeed!

Renowned historian J. N. da Fonseca, who purchased the Faria estate in the nineteenth century, built a house there, possibly on the ruins of the hypnotiser’s family house. Only the private chapel was spared.

When I was working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m

working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

So, you see, it was great getting to know Abade Faria – my civic duty, to say the least. You too can trail him now. Begin today, on his 200th death anniversary.

(Herald Café, 20 September 2019, p. 1)

https://www.heraldgoa.in/Cafe/WHEN-I-MET-ABADE-FARIA%E2%80%A6/151383

Yuletide Recollections

Solemnising the dogma of the Immaculate Conception at the city church (8 December) was a good spiritual preparation for Christmas just round the corner. The angelic music of the Salves at twilight prefigured the celestial choirs intoning "Gloria in Excelsis Deo" a fortnight later. Caroling house to house, late in the evening, was the order the season (the proceeds went to Mother Teresa's Asilo). City clubs like Nacional and Vasco da Gama organised carol singing competitions, balls and street dances. The household would be agog with the Crib, the Star and the Christmas Tree.

24th December: after the Midnight Mass, we used to head straight for the pillow to herald Pai-Natal (Christmas Father) in our sleep. We woke up the next morning, excited about the festa da família (family celebration) – more recently, a veritable family reunion at lunch or supper! We particularly relished the consoada (meaning, the season's sweets, in Goa) comprising traditional homemade delicacies that Avó (Grandmother) Leonor insisted on having for Christmas.

The days that followed, up to 6th January, feast day of the Reis Magos (the Magi, or Three Wise Kings) at Verem, saw Panjimites on their evening beat around the city. They invariably walked up to Timoteo's mechanised crib, or drove to Francisco Martins' at Ribandar. Other private houses and public squares used colourful lighting.

Once upon a time, that was my Christmas agenda. Much of it has gone but some of it has remained in the form of a musical reverie, thanks to Jim Reeves, my childhood star who still sings "Jingle Bells", "Silent Night", "Mary's Boy Child" and "White Christmas".

(First published in Panjim Plus, 16-31 December 2001)