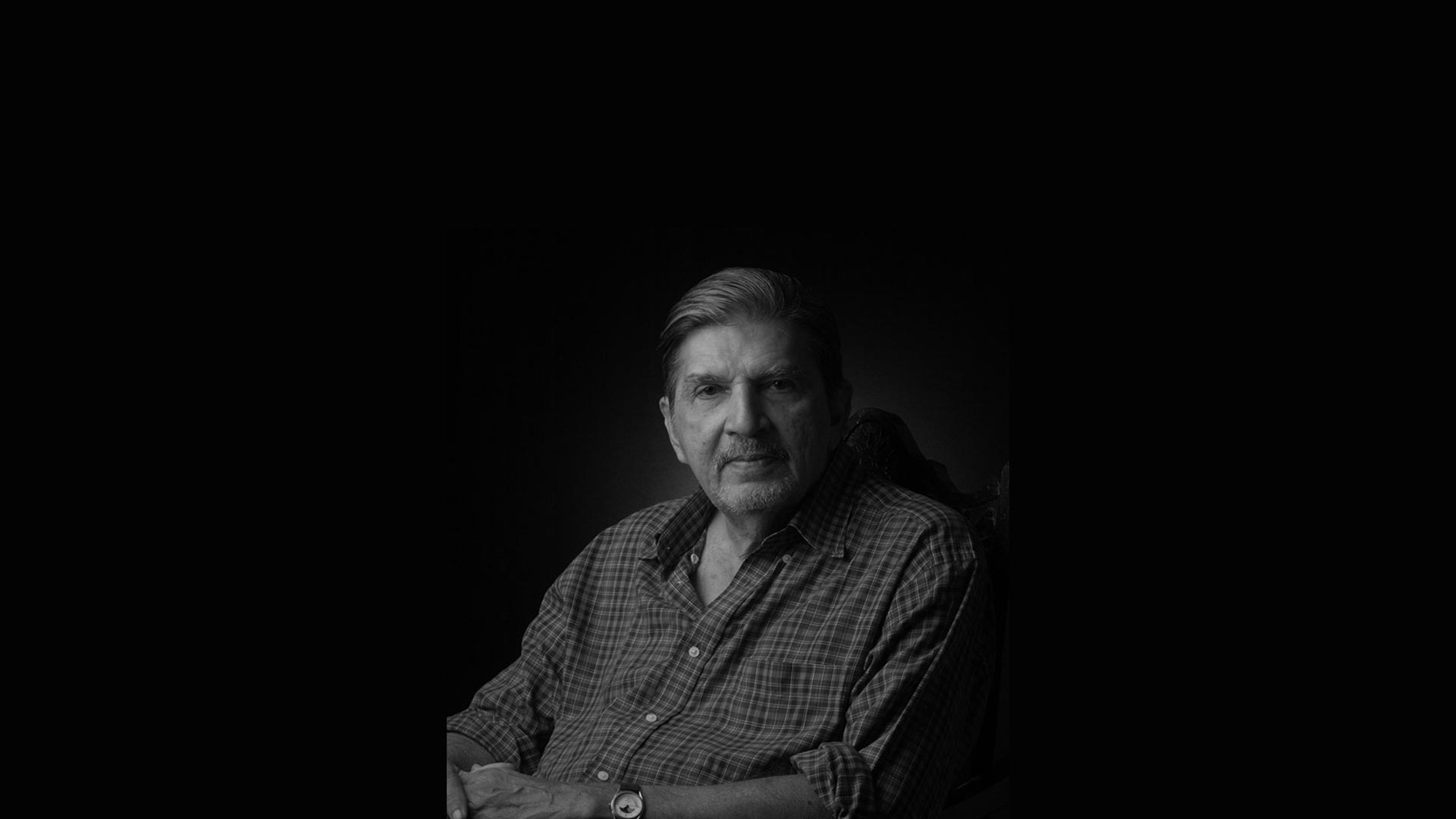

Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 2/6)

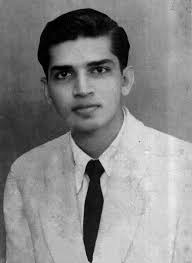

The Artist as a Young Man

The Artist as a Young Man

It was during his college days in Bombay that Mário’s characters first strutted out of his diaries; he drew pocket cartoons and peddled them at Flora Fountain for pin money.[11] And at a medical ball held at Clube Vasco da Gama, Panjim, couples dancing the night away delighted in the frisky sketches of the faculty members that Mário kept drawing on the wall mirrors lining the ballroom.[12]

It is not that Mário always passed uncensured. One day, a priest from the village, whom he had depicted outside the local fish market, showed up at his house. Mário’s mother, after doing her best to placate the visitor, ended up going to see archbishop Dom José da Costa Nunes, who had once expressed his wish to meet the young artist. Mário was hesitant but once there, was relieved to see his diaries spark guffaws rather than a controversy. ‘That was the first time I was appreciated by someone I didn’t know,’ he said.[13]

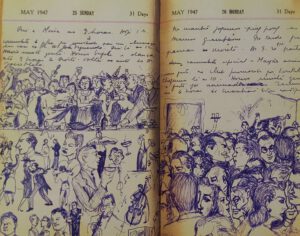

Mário maintained a diary right through his years spent in British India with intermittent stays in Goa and Damão (Figure 2). The last three logbooks (1949-51),[14] now available in print, are a shrine of frolicky pictures of relatives and friends in Loutulim, Panjim and Margão.[15] To quote Nissim Ezekiel, ‘the buffoonery of his human figures is redeemed from grossness by their verve, their inner urge towards going places, getting somewhere. It is not always their fault that there is no place to go, nowhere to get except through the corridors of illusion.’[16]

That was Mário’s equivalent of the dark night of the soul! His lifestyle was a cause of concern to his by now widowed mother struggling to manage the household while at the same time providing for Pedro at Princeton University.[17] But then Mário had a change of heart: was it the showcasing of his watercolours and drawings by the 1950 Souvenir of the Bombay-based Loutulenses League[18] that did the trick?

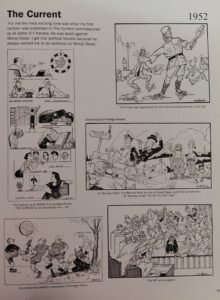

In 1951, seeing a bleak future for himself in Goa, Mário moved to Bombay. Though creative possibilities seemed unlimited here, he was jobless and quite badly off at first. That’s precisely when Policarpo (Polly) Vaz, a fellow hosteller at Rockville,[19] famously suggested to him to hand-craft picture postcards depicting the city monuments, offering to sell them at the hotel where he worked the night shift. Needless to say, the two became fast friends; and they had even thought of migrating to Brazil,[20] when Mário got a call from D. F. Karaka of The Current. The redoubtable editor, riveted by Mário’s diaries, commissioned him to cover a can-can dance scene at the Taj Hotel, and received such a rib-tickler that he promptly took him on as the tabloid’s regular cartoonist.

The young Goan created a stir in Bombay's journalistic circles when his cartoons first appeared in the press. Editor C. R. Mandy and art director Walter Langhammer soon invited him to The Illustrated Weekly of India. Before long, other Times Group publications,[21] too, began to use Mário’s drawings; they skilfully portrayed movement and sound, and often featured the cartoonist’s trademark dog.

Art of Cartooning

That was the year 1952. Mário had virtually stumbled into the profession of cartooning.[22] To an onlooker the job seemed easy, and everything grist to the mill – from the bureaucracy, fashions, business, and people’s habits, to the animal world, environment, music, society, and even politics – but really, finding humour was no mean task. ‘There are times when you don’t feel funny, or may not feel like laughing, but still have to produce a funny cartoon – like a clown who has got to make people laugh all the time, although he doesn’t feel like laughing.’[23]

Elaborating on his predicament, Mário said, ‘People expect me to come up with jokes and anecdotes to make others laugh. I can’t do that. I enjoy humour if it comes from someone else who knows how to tell a good joke…. I am not a naturally funny person; I may look funny, but I am not funny.’[24] And if a cartoonist’s defining quality it is ‘to detect funniness in people’s behaviour or physical features and draw it, it is equally important to be able to laugh with someone, not at someone, without being cruel,’ said Mário, adding: ‘Humour is something very personal, individual. What’s funny to me may not be funny to you. Sometimes I do something which I think is very funny – and it flops! And people asking you to explain a cartoon flattens it completely.’[25]

Past the initial scramble for work, Mário began to yearn for the blissful spontaneity of his diary sketching. Add to this the fact that political bigwigs were breathing down his neck, and Mário had a sure recipe for disenchantment. Bombay Presidency’s Home Minister Morarji Desai was among the first ones to let his irritation show – something that taught Mário early on that lampooning political animals involved high risk. When he toned down the humour to appease the readers, cartooning quite paradoxically became a ‘serious business’. ‘Cartoonists are very serious people, and cartoons, no laughing matter,’[26] he quipped.

Finally, Mário stopped pursuing individual politicians; he began to see himself as a social caricaturist more than anything else. He is on record as saying, ‘I am not even a cartoonist; I draw… give me a pen and blank paper and I will draw. I just love to draw.’[27]

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[11] ‘Tale of Two Goans: Mario Miranda & Wendell Rodricks’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5FDLGApfATc&t=5s

[12] Cf. Fernando de Noronha, Momentos do meu passado (Goa: Third Millennium, 2002), p. 146.

[13] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[14] Cf. The Life of Mário (1949, 1950, 1951) ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous), in 2016, 2012 and 2011, respectively. Fátima Miranda Figueiredo reckons that her brother’s diary sketches total up to about 6,750 over a period of 18 years (1934-1951).

[15] He frequented the houses of his relatives, Judge António Miranda and Captain Adolfo Menezes, in Panjim, and Judge Eurico Santana da Silva, in Margão; and often stayed overnight with friends in their hostels.

[16] Nissim Ezekiel, ‘No escape if Mario is looking at you,’ in Mário de Miranda, ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous, 2005), p. 276.

[17] As told by Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021.

[18] Souvenir of the Silver Jubilee of the Loutulenses League (Goa: Imprensa Nacional do Estado da Índia, 1950). Curiously, in the chapter titled ‘The Rising Generation’, Mário figures as an Arts graduate, not as an Artist.

[19] Polly was from Bastorá; other hostelites, Joe Albuquerque and Paulo Miranda, from Loutulim. Cf. Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 14.

[20] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 15.

[21] Femina; Filmfare; The Evening News and The Economic Times.

[22] Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[23] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 24; Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

Remembering Leonor

Paying homage to the dead is a cardinal civic virtue, an expression of gratitude that also helps to imbibe sterling values perhaps scarce in a new day and age. And this is what links us to Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, who was born on 24th May 1909 to Miguel de Loyola Furtado and Maria Julieta de Loyola. Married to Martinho António Fernandes, she was essentially a matriarch and a grand lady of the Fourth Estate.

Leonor was a career woman with a difference. A mother at 16, it was after this that she began writing in earnest, without letting this disturb her duties as a housewife. Her husband encouraged her to fight for her ideals through the weekly A Índia Portuguesa, and bore the brunt as Administrator of the Comunidades of Salcete, dogged as he was by controversy fuelled by a mix of personal vengeance and political vendetta.

Although Martinho eventually emerged unscathed, it was not easy for Leonor to weather those storms while she raised four daughters. A grandmother at 39, two years later she took over the said weekly, a family heirloom and historic mouthpiece of the political party called Partido Indiano, becoming the first lady editor in the whole of the Portuguese speaking world and in the Indian sub-continent too.

In 1951, she travelled to Portugal, the sole lady in a five-member media delegation from Goa invited to see the ‘mother country’. Portugal had then renamed its colonies ‘Overseas Provinces’, considering them an integral part of a far-flung Portuguese State. Leonor wrote about what had impressed her, not forgetting the meeting with Premier Oliveira Salazar, the Minister for Overseas Territories, Sarmento Rodrigues, and the pressmen with whom she spoke on different aspects of life in Goa.

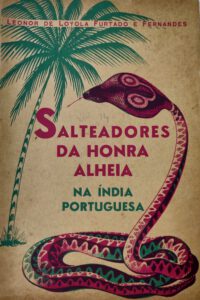

Her trip of 1956 was marked by the publication of her first book, Salteadores da Honra Alheia na Índia Portuguesa (‘Assailants of People’s Honour in Portuguese India’), whose arresting title and explosive content led to its confiscation in Goa. While she wished to publicize the truth about her husband’s professional troubles, evil doings of prominent individuals and shady workings of many a public institution got exposed too.

Leonor was a champion of civil liberties by virtue of her journalism. As a proud descendant of one of Goa’s best known families involved in the civil rights movement, she took to it like fish to water. While critical of the administrative faults of the Portuguese regime, she was a moderate in her political aspirations, open to the ideas of decentralization and greater financial autonomy for Goa, and more importantly a zealous protector of the Goan identity, in the pre- as well as post-1961 regimes.

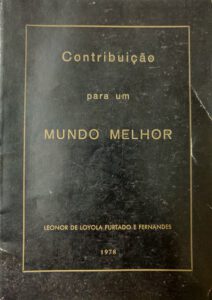

Her second book, Contribuição para um Mundo Melhor (‘Contribution for a Better World’) shows her love for Goa but does not camouflage her combative spirit. It has interesting reflections on the period spanning 1961-78; her missives from Portugal, Angola and Mozambique (August-October 1969); historical snippets about her newspaper; the story of the legendary José Inácio de Loyola Sr.; and photocopies of historic telegrams of the tumultuous days of September 1890.

Under the new political dispensation, her journal had to change its name to A Índia – just ‘India’! She was smart enough not to grudge this. But what provoked her ire was that the Comunidades had been given short shrift in a chaotic democratic state. In 1966, when interviewed by the redoubtable D. F. Karaka, Leonor fulminates against the police for searching her residence by night, looking for components of bombs and other subversive material used in the Vasco bomb case. Frustrated with their sole discovery, a book titled , her Indian passport was impounded and censorship was imposed on her paper.

The intrepid journalist declared that “her fight was against all governments who tried to deprive the people of civil rights and who imposed censorship, whether it was a Portuguese censorship or the censorship dictated by the Indian Government.” And some of her statements to the Bombay tabloid have a familiar ring even today: “The administration has gone rotten. In the (Goa) Assembly, the Opposition has accused the Government of nepotism, communalism, inefficiency and incompetence…. Laws have been passed without going into the constitutional right of the people,” she complained.

To redress her own grievances against the Government of Goa, she either met or wrote to Indira Gandhi every time. In her letter of 19th February 1966, she declared, “I believe in a Power above the powers of the world and in justice that comes, sometimes in time, at other times a bit late, in some manner or the other.” The restrictions were soon lifted, by a letter dated 13th May 1966, the significance of which day was not lost on Leonor: she was a great believer in the Message given on this day, half a century earlier, by the Mother of Jesus, when she appeared at Fatima, Portugal.

Leonor was truly blessed with a deep and empowering faith, or else she would not have endured as a career journalist until December 1975. And, not surprisingly, when the Angel knocked at her door on 8th January 2005, he must have found Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, at the ripe old age of 95, still steadfast in her principles and faithful to her people.

(Goa Today, June 2009)

Remembering Leonor: Editor Extraordinaire

To the dead it probably matters little whether or not they are remembered: having done their bit on earth they now belong to Eternity, where worldly honour and glory are of no consequence. But paying them homage is a cardinal civic virtue – an expression of gratitude for the valuable services rendered by them to the community, which also helps to imbibe sterling values that might well be scarce in a new day and age.

That is what links us to Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes on her birth centenary. Born on 24th May 1909 to Miguel de Loyola Furtado of Chinchinim and Maria Julieta de Loyola of Orlim, she was married to Martinho António Fernandes of Colvá. She was a woman of many parts but essentially a matriarch and a grand lady of the Fourth Estate.

Wife and Mother

Leonor – Lolita, in her close circle – was a person ahead of her times. She was a career woman with a difference. When the Panjim-based eveninger Diário da Noite (2nd May 1953) asked about the beginning of her occupation, she said, ‘I don’t remember clearly when I started writing. I know I became a mother at 16 and it must have been after this that I began writing in earnest.’

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

And reflect it did. As Administrator of the Comunidades of Salcete, Martinho Fernandes, a lawyer by training, was dogged by controversy, initially fomented by individuals who eyed his post, while later some of it was fuelled by a heady mix of personal vengeance and political vendetta, thanks to his wife’s plain speaking in the weekly A Índia Portuguesa. The incumbent emerged unscathed, through long and tortuous battles up to the apex court.

It must not have been easy for Leonor to weather those storms while she raised four daughters, managed the household chores and the family estates. But the years rolled by and, interestingly, at 39 years of age, she was already a grandmother! In 1950, when that venerable journal, a family heirloom and historic mouthpiece of the pro-native political party called Partido Indiano, founded by the Loyolas of Orlim, was almost folding up, it was born again with Leonor.

Journalist and Author

It was for the first time that in the whole of the Portuguese speaking world and in the Indian sub-continent as well a woman was at the head of a newspaper. This was only a natural consequence of having her father for a role model: apart from being a brilliant physician and political leader, he had edited A Índia Portuguesa from the year 1912 until his sudden demise in 1918, and his memory remained with Leonor for the rest of her days. She once said, ‘If destiny were not opposed to it, I would have studied medicine. I had a fascination for the medical profession, so as to positively spread the good to all. But I was born for something else – and I am a journalist only. I would have liked to be a physician and journalist.’ (Diário da Noite)

A year after assuming editorship she travelled to Portugal, the only lady in a Goan media delegation comprising Fr Manuel Francisco Lourdes Gomes, Álvaro de Santa Rita Vaz, Amadeu Prazeres da Costa and Luis de Menezes Jr. They had been invited for a month’s stay, to see for themselves what the ‘mother country’ was like. It was a public relations exercise by the Estado Novo, for in March that year the Government had passed an amendment to the controversial Colonial Act, renaming the colonies ‘Overseas Provinces’ and considering them an integral part of a far-flung Portuguese State. The change of nomenclature reinforced the one-nation theory, in a bid to counter global pressure against European colonization in the post-World War scenario.

The exercise paid dividends. Members of the delegation sent regular reports to their respective newspapers. On her return, Leonor wrote about what had impressed her, not forgetting the meeting with Premier Oliveira Salazar and the Minister for Overseas Territories, Sarmento Rodrigues. She had spoken to pressmen from continental Portugal and its overseas provinces on different aspects of life in Goa.

This was the first and surely the most memorable of her many visits abroad. Her official trip of 1956, on the fortieth anniversary of Salazar’s New State, was marked by the publication of her first book, Salteadores da Honra Alheia na Índia Portuguesa, (‘Assailants of People’s Honour in Portuguese India’). The curious little book’s arresting title and explosive content prompted the Portuguese Governor-General Paulo Bénard Guedes to have it confiscated on its arrival in Goa. While the author’s primary intention was to publicize the truth about her husband’s professional troubles, these are universalized, turning the book into a “repository of truths that make up our life in India.” The picture of a coconut tree and a cobra on its cover probably point to the coexistence of indolence and poison in our land. The evil doings of some prominent individuals and the shady workings of many a public institution are exposed.

Civil Rights Activist

Leonor was a champion of civil liberties by virtue of her journalism. As a proud descendant of one of Goa’s best known families involved in the civil rights movement, she took to it like fish to water. While critical of the administrative faults of the Portuguese regime, she was a moderate in her political aspirations, open to the ideas of decentralization and greater financial autonomy for Goa, emanating from the new Lei Orgânica do Ultramar, and more importantly a zealous protector of the Goan identity, in the pre- and post-1961 regimes. This was clear from her statement upon taking her seat in the legislative council of Portuguese India, in 1961: ‘Regimes fall, empires vanish, ideologies die, but the land remains, and we have to work for Goa to remain forever.”

Leonor was now left to fight life’s battles alone. She had lost her husband in 1960; and under the new political dispensation, even her journal had to change its name to A Índia – just ‘India’! She was smart enough not to grudge this, given the fait accompli of the Indian take-over of Goa. But what provoked her ire was that the Comunidades were being given short shrift, enough to have Martinho Fernandes turn in his grave.

In her second book, Contribuição para um Mundo Melhor, a tribute to her husband, printed on her last visit to Lisbon, in 1978, she addresses him on his life's interest, saying, "Do you see the state of our land today, how the Comunidades are faring, and how the land is groaning under injustice?" (p. 8) “Because our people are not rebellious and have not lost their sense of discipline and honesty, there has been no revolution yet,” she thunders (p. 14). It is clear that although she wishes to reconcile everything under a positive title (‘Contribution for a Better World’) nothing can camouflage her combative spirit.

Eye-opening Interview

![]()

In 1966, The Current, a well known weekly published from Bombay, invited readers to send in entries for an interview competition to mark the publication’s 18th anniversary. Leonor submitted her experiences as editor of A Índia. As one of the four short-listed, she was interviewed by the redoubtable D. F. Karaka, who, curiously, twenty-three years earlier, had been mentioned as one of her favourite authors. It was a rendezvous of two editors sans peur et sans reproche…

The picture of Leonor that accompanied her “interesting entry” was considered “almost as threatening as the entry itself”. On the morning of the interview, a tornado was expected to blow into the newspaper office, bearing a flaming torch in one hand and a sword in the other. Although Leonor fulminated against the police for searching her residence by night, looking for components of bombs and other subversive material used in the Vasco bomb case, “the tornado from Goa was only a gentle breeze”, wrote Karaka. Frustrated with their sole discovery, a book titled Invasion and Occupation of Goa (National Secretariat for Information, Lisbon, 1962), containing world press reports on the contentious Goa Question, her Indian passport was impounded when she was on a visit to New Delhi and, back in Goa, censorship was imposed on her paper, with a heavy bond and two sureties made necessary to ensure “due performance of the restrictions”.

The intrepid Goan journalist stated that “her fight was against all governments who tried to deprive the people of civil rights and who imposed censorship, whether it was a Portuguese censorship or the censorship dictated by the Indian Government.” She especially decried censorship under a democratic set-up. “I wanted to publish in my paper extracts from Inside, which is a Swatantra Party paper. These quotations were cut out by the censors,” she said.

Final Years

Some of her statements to the Bombay tabloid have a familiar ring even today: “The administration has gone rotten. In the (Goa) Assembly, the Opposition has accused the Government of nepotism, communalism, inefficiency and incompetence…. Laws have been passed without going into the constitutional right of the people,” she complained.

While she made a case for the preservation of the Goan identity, showing her red-pencilled extracts of Nehru’s speech at Siddharth Nagar, Bombay, on 4th June 1956, to redress her own grievance against the Government of Goa, she either met or wrote to Indira Gandhi every time. In her letter of 19th February 1966, she declared, “I believe in a Power above the powers of the world and in justice that comes, sometimes in time, at other times a bit late, in some manner or the other.” The restrictions were soon lifted, by a letter dated 13th May 1966, the significance of which day was not lost on Leonor: she was a great believer in the Message that the Mother of Jesus gave on this day, half a century earlier, in her apparition at Fatima, a place Leonor visited on several occasions.

Her meetings with Mrs Gandhi are recounted in Contribuição, which also carries interesting reflections on the period spanning 1961-78; her missives from Portugal, Angola and Mozambique (August-October 1969), which though “innocuous” were responsible for her passport problems yet again; historical snippets about her newspaper; the story of the legendary José Inácio de Loyola Sr.; and photocopies of historic telegrams of the tumultuous days of September 1890.

Karaka had found it “heartening to see a woman in her 50s, who had been so disturbed by the turmoil of politics, still crusading for the rights of the people and still having faith in a Power above the powers of the world.” Leonor was truly blessed with a deep and empowering faith – or else she would not have endured as a career journalist until December 1975. She said, “I have great faith in Our Lady. Although I have been harassed in my life by the powers on earth, I have never cared or worried.” And not surprisingly, when the Angel knocked at her door on 8th January 2005, he must have found Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, at the ripe old age of 95, still steadfast in her principles and faithful to her people.

(Herald, 'Mirror', Sunday magazine, 24.05.2009)