Holy Passion Processions in Panjim

At the Church of the Immaculate Conception – the Igreja Matriz or main parish church of Panjim – the sixth Sunday of Lent begins on a festive note. It is Palm Sunday, which commemorates the triumphant entry of Jesus in Jerusalem.

However, after the morning Masses, there is a visible change in the mood, especially with the unveiling of the tableau in the chancel: a larger-than life-size statue of Christ carrying the Cross. Hence, the day's alternative designation: Passion Sunday.

The evening of Passion Sunday features a solemn procession that begins from and ends at the iconic church. It is the highpoint of the Santos Passos (‘Holy Steps’) held on the first five Sundays of Lent, highlighting some of the most intense moments of Christ’s Passion leading to Calvary: the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane; the Arrest of Jesus; the Flagellation at the Pillar; the Crowning with Thorns; the condemnation by Pontius Pilate (See my blogpost https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2019/03/17/santos-passos-in-panjim/ ). Other churches in Goa do not necessarily have the same set-ups (See https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2021/03/21/lenten-traditions-in-goa/ ).

Passion Sunday signals the beginning of the Holy Week. The predominant colour is purple; the altars are bare and there is not a flower arrangement to be seen. After the evening Mass, a procession called Cruz às costas – the same tableau of Jesus carrying the Cross – wends its way through some of the main thoroughfares of the capital city: the Church square, a section of 18 June, Pissurlencar, past Azad Maidan.

Confrades (Church confraternity members) wearing opa e murça (a red and white cape) carry the statue concertedly, giving the impression that it is floating on its own power. In the past, a brass band would follow; but nowadays, a choir sings from an intermediate landing of the church's zigzag stairway. The singing and prayers are heard throughout the route via funnel loudspeakers. The procession is animated by the recitation of five Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary until the end of the procession.

The circuit is marked by over ten descansos (halts), at which points the faithful flock to kiss the statue. A major halt happens at the Capela da Conceição (Chapel of the Immaculate Conception). Built in 1823, it was once a private chapel attached to the mansion of Dom Lourenço de Noronha, scion of a Portuguese noble family, and was later bequeathed to the Confrarias of Panjim church and has been under repairs since 2019.

The cavalcade then proceeds via M. G. Road and Dr D. R. de Sousa, past the Garcia de Orta Garden, and up to the church square. Here, at the foot of the stairway, Jesus is met by His Blessed Mother. Sorrowing over her Son so unjustly accused and made to carry the Cross to His death, she accompanies him on his last last legs, as she did two thousand years ago to Golgotha.

Soon thereafter, the two statues halt on the intermediate landing in front of a large cross carved out of the wall. A level higher, from a pulpit-like balcony jutting out of the said wall, a little girl unrolls the Veil of Veronica while she sings the traditional narrative. This is about the meeting of the legendary woman (feast day, 12 July) with Jesus. As recorded in the fourth station of the Via Crucis (Way of the Cross), Veronica, moved by the sight of Jesus carrying the Cross, wiped his brow with her handkerchief only to find a lasting imprint of his holy face on the cloth.

Thus ends Passion Sunday and preparations begin for the Holy Triduum beginning on the evening of Maundy Thursday. This day, which comprises a Mass with the reenactment of the historic Washing of the Feet by Jesus, marks the institution of the Eucharist and the Priesthood and the proclamation of the Commandment of Love. There is no public procession.

Five days later, on Good Friday, the processional arrangement is the same as on Passion Sunday, except for a few obvious differences.

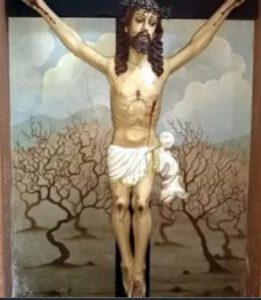

The poignant Crucifixion tableau opens in the chancel at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. It is interesting how by then the sky is usually cloudy and the mood sombre. The liturgy of the Word and the Eucharist continue until at about half past five. Then, a procession of a larger-than-life-size statue of Senhor Morto (The Departed Lord) placed on an andor (black canopied wooden platform) starts off, with the statue of Our Lady in trail.

There are some other differences too. Today, the faithful are in funereal attire, which once upon a time was de rigueur. And instead of the sanctus bell, we hear the matraca or wooden rattle at every halt in the procession.

A major difference between the Passion Sunday and the Good Friday procession lies at their very end. This time round, in a coda to the baroque event, is the Sermão da Soledade de Maria (Sermon on the Solitude of Mary) delivered by a priest from the same pulpit-like balcony. The preacher extols the virtues of Mary and highlights her present solitude. Formerly, rhetoric played a crucial role on such occasions, helping to fully engage the congregation. Nowadays, the limited number of faithful who stay on to listen are easily distracted, not least by vehicle noises that detract from the solemn ambience.

In this context, one striking similarity between the processions is that both are watched in awe by people of other religions. On both occasions, residences put up decorative lights, candles or oil lamps in homage to Our Lord. Some non-Christian establishments remain open, it being a weekday, do the same. People from other religions watch in awe, including policemen (one of whom I saw standing at attention and saluting the Departed Lord). Particularly interesting is the case of the Caculos and the Neurencars, two Hindu families on Pissurlencar Street; they traditionally offer garlands of xenvtim or abolim.

Depending on the number of attendees, the pious, kilometre-long march and related ceremonies on both days take between 75 and 90 minutes. The statues return to the church for concluding rites and veneration. By 8 o’clock, they call it a night!

Behold two processional events in Panjim that have left a lasting imprint on my mind. So was it when my life began; so is it now I am a man. So be it when I grow old – for this ancient tradition is without a doubt one of the most moving spectacles in the religious and cultural calendar of my city, Panjim.

Requests:

1- In the comments section below, do share snippets of similar traditions in your village or city, and document them whenever possible.

2 - Do watch my video titled "Passion Sunday Procession in Panjim", on http://www.youtube.com/@oscardenoronha

From Carnaval to Carnival

| To the Anglo-Saxons, ‘Carnival’ is a travelling fair or circus; to the Latins, or say, the Portuguese, Carnaval is a period of enjoyment or euphoria before Lent. Despite this Christian reference, Carnaval is far from being a religious festival. It is a cultural remnant from pre-Christian times, when the orgiastic Saturnalia was celebrated with tableaux in Rome and Athens.

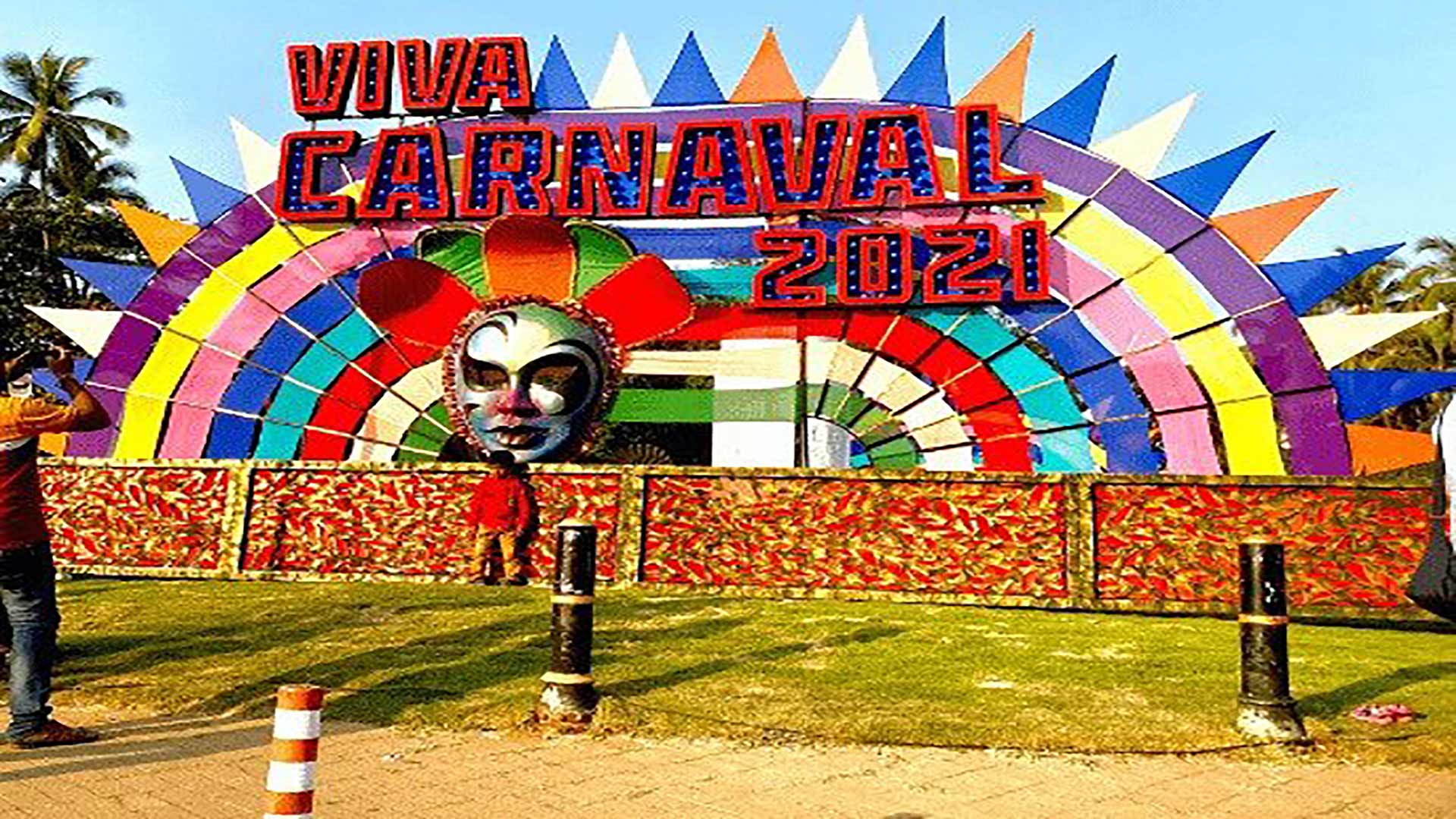

The festival came to Goa via the Portuguese. At first they used the word Entrudo, of which Intruz is now a Konkani corruption. But given that Entrudo means ‘introduction’ one wonders how epicurean delights can ever be a good introduction to the austerity of Lent! For that matter, the word Gordo, as in Sábado Gordo (Fat Saturday) probably referred to people’s overeating and drinking. As a child, the expression brought to mind those silly, larger-than-life characters that walked the streets on the days of Carnaval. Of course, nowadays, it is the fat profits that the season brings in that better justify the use of the word! In town and country Although in Goa Carnaval and Intruz are sometimes used synonymously, locals know the difference: the former is city-based, cosmopolitan, sophisticated, while the latter happens in the countryside and has a plebeian feel. Anyway, revelry begins on Saturday afternoon and ends on the eve of Ash Wednesday. The festive atmosphere is more pronounced in the Old Conquests, where the Christian presence is larger; and the celebrations in the towns are noisier than in the villages. I remember my grandmother’s take on her childhood Carnaval in Pangim way back in the 1910s. Although it was marked by a lot of tomfoolery, ‘that fun was free of malice,’ she said. No doubt, there was a method to the madness of those who took to the streets in bizarre attires. They shook out talcum powder tins on friends and acquaintances, or used aluminium tubes to spray them with scented water. Youngsters – especially Lyceum lads staying in Repúblicas (hostels) – and the descendentes or mestiços, delighted in burning firecrackers or drenching passersby.[1] The city elite living around Garcia de Orta Garden Square, and families from elsewhere, went round in horse-drawn carriages and engaged in mock battles using confetti or streamers. In those days, even the governor-general played cocotes (paper cartridges containing white powder or coloured sawdust). In the 1930s, the city clubs were known for their soirées and Japanese matinées. These were informal gatherings – and ‘Japanese’ because, artist and Carnaval enthusiast Alfredo Lobato de Faria once told me,[2] Goa was then flooded with dainty Japanese products that they used on the occasion. The parties were held at Clube Nacional, which had a large ethnic Goan membership; at Clube Vasco da Gama, which was the bastion of Europeans and their hangers-on; or at the short-lived Clube Recreativo that the city merchants had set up. Such events helped the old and the young alike to unwind as they made music with family and friends; but the very pleasure of partying is said to have disappeared after World War II. In his coffee-table book titled Goa, Mário Cabral e Sá says that “Carnaval in Goa was a great leveller. Early accounts – all of them hearsay – are indeed educative. The white masters masqueraded as black slaves, and the latter – generally slaves brought in from Mozambique – plastered their faces with flour and wore high battens or walked on stilts. For those three ephemeral days, they were happy to be larger than life. And while the ‘whites’ and the ‘blacks’ mimicked each other, the ‘brown’ locals watched this reversal of roles in awe from the sidelines.”[3] The spirit of the season in our cities, towns and villages is still marked by friendly exchanges. People mix freely in a riot of colour. Way back, folks made cardboard masks and hats, covered them with tinsel, and launched assaltos (mock assaults), that is, surprise visits to friends’ houses, amusing the household and frightening unwary passers-by with their antics. Boys used chiknollis (bamboo syringes) or plastic tubes and guns, to spray coloured powder; and they painted girls’ faces, just when they least expected it, and seized the opportunity to confess their love! The village dramatist was a typical Intruz figure who spun humorous anecdotes and weaved a social critique at the itinerant khell (Konkani theatre play) with song and dance. The Kunnbi and Gauddi lot, presently free from agricultural tasks, were glad to perform, be it in the shade of a tree, in the balcony of a vacant house, or at the local bhatkar’s. One could watch them in Curtorim and Margão’s Gogol ward.[4] In fact, every village in Goa has its own little Carnaval or Intruz. The picturesque island of Divar is known for the Potekar festival.[5] And in Village Goa,[6] Olivinho Gomes describes Chandor’s mussoll-khell, a pre-Portuguese dance-theatre that has evolved down the ages. However, in the last five decades the spotlight has been on a single event – a state-sponsored parade held in Panjim and other towns.[7] The show draws thick crowds from every nook and cranny, but, unlike in the past, they now come as mere spectators, hardly inclined to participate spontaneously. Carnaval vs. Carnival It is difficult to say when Carnaval entered the Goan cultural calendar. What is well known, however, is that when the UN declared 1967 as International Tourist Year, with the slogan ‘Tourism, Passport to Peace’, Percival Noronha, a senior official of the Goa government, conceived the idea of the city parade that is held today, with King Momo announcing his reign of fun. The plan was executed by Vasco Álvares, long-time Chief Officer of Panjim Municipal Council, supported by his sons Manuel and Roberto, Francisco Martins, and others.

Timóteo Fernandes, another aficionado, was the first King Momo. The tableaux attracted tourists and locals alike. Hoping to take the show to another level, the government approached liquor and hotel industries, and their funding has since become indispensable. Clube Nacional’s Red & Black Dance held on Panjim’s main artery was the rage, and like Margão’s Harmonia and Bernardo Peres da Silva club balls, raked in a lot of money. No doubt, organising fancy dress contests, arranging costumes and decorating the venues was not kid’s stuff; it called for brainstorming and research, physical effort and coordination. But eventually it became a whole new ball game. That is how and when the traditional Goan Carnaval turned into a new-fangled, commercial Carnival. Of the old-style festival, only the slogan remained: ‘Viva Carnaval!’; its soul had vanished into thin air. With the cultural agenda thus commercialized, the festival was stripped of its simplicity and spontaneity. Those who have seen it evolve say that the comic element gradually crossed the limits of decency – and turned garish and tragi-comic! In the 1980s, the Church in Goa denounced the use of indecent attires, intoxicants and drugs under cover of Carnival. In 1987, people boycotted the festivities, protesting the delay in recognizing Konkani as Goa’s official language. The State machinery revived the festivities in the 1990s, but Carnival-weariness had already set in. Disgruntlement left a mark, at least by way of veiled messages that the floats displayed. Even so, the Carnival bandwagon has moved on, fuelled by money, feni and more. It stations itself at Garcia de Orta Garden Square, specially renamed ‘Samba Square’ for the season. There are food and liquor stalls, music, dance and revelry galore, but missing is that authentic spirit of Carnaval… In a bid to draw attention to the only Latin festival in an Indian setting, why conjure up a picture of Brazil? All one had to do was change ‘Carnival’ back to our very own Carnaval! |

[1] Fernando de Noronha, Goa tal como a conheci. Goa: Third Millennium, 2018, p. 129.

[2] See Alfredo Lobato de Faria’s interview on Renascença Goa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

[3] Mário Cabral e Sá and Jean-Louis Nou, Goa. New Delhi: Lustre Press, 1986, p. 44

[4] Cf. Vince Costa’s short film titled ‘Chotrai, khellpolloinarank chotrai’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

[5] Celina de Vieira Velho e Almeida, Feasts and Fests of Goa: The Flavour of a Unique Culture. Panjim: Self-published, 2023, pp. 24-27.

[6] Olivinho Gomes, Village Goa. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co., 1996, p. ___; Zenaides Morenas, The Mussoll Dance of Chandor. Goa: Self-published, 2002.

[7] Carnival 2025 I Doordarshan Goa I Live Telecast of the Panjim Carnival Parade, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nnvgbl-Sc_U

Mauzó recebe o galardão Jnanpith

“My language has never let me down," says Writer Damodar Mauzo

"A minha língua nunca me decepcionou," disse o escritor Damodar Mauzó.

Reportagem de Brian de Souza | Traduzido do inglês por Óscar de Noronha*

No seu discurso de aceitação do galardão Jnanpith, Damodar Mauzó discorreu sobre as suas inspirações criativas; sobre o que lhe representa o concani; e a necessidade de criar uma atmosfera que garanta a liberdade de expressão.

“Inspiro-me na minha terra natal, no meu povo e na minha língua”, disse Damodar Mauzó no seu discurso de aceitação do prestigiado prémio literário Jnanpith que lhe foi conferido, relativo ao ano de 2022.

Mauzó recebeu o galardão após a leitura da citação, numa cerimónia muito concorrida, realizada no Raj Bhavan, residência oficial do governador de Goa, P. S. Sreedharan Pillai, em maio de 2023.

“Na expressão das minhas ideias, a minha língua nunca me decepcionou”, reiterou Mauzó, de 78 anos, no seu discurso. Essas palavras captaram a essência da sua longa caminhada com a língua concani, que disse que ama e a qual, “por sua vez, muito me ama”.

Então, por que escreve Mauzó? Disse sucintamente: “Escrevo porque tenho algo diferente a contar e/ou a contar algo diferentemente”.

É apenas o segundo escritor da língua concani a receber este prémio; o primeiro foi o falecido Ravindra Kelekar, quem Mauzó cortesmente reconheceu como seu mestre. Kelekar liderou o movimento literário goês no pós-1961.

A obra literária de Mauzó é vasta e inclui vários géneros. Na sua carreira de 50 anos, publicou 6 colecções de contos, quatro romances, dois esboços biográficos, livros infantis e um grande volume sobre a saga do concani, no qual descreve as dificuldades sofridas à conta dos sequazes da língua durante o regime colonial português.

Mauzó publicou a sua primeira colecção de contos, Ganthan, em 1971, porém, foi só em 1983 que alcançou fama pelo país inteiro, com o romance Karmelin, sem dúvida, a sua obra mais conhecida, com a qual venceu o prémio da Sahitya Akademi. Nesse romance, Mauzó destaca as lutas de uma goesa que, para o seu ganha-pão, se desloca para o Médio Oriente. Escrito no auge da emigração goesa para o Golfo Pérsico, foi bem recebido e traduzido para 14 idiomas. É uma obra seminal sobre a experiência goesa nessa parte do mundo.

Dizendo-se um leitor voraz, Mauzó também prestou homenagem, entre outros, a escritores como Mahasweta Devi, José Saramago e M. T. Vasudevan Nair, os quais disse admirar. Também reconheceu a influência de Saratchandra Chattopadhyay, escritor bengali, que, segundo Mauzó, falou da sua dívida para com os necessitados (“suas lágrimas e desamparo”), que dão tudo, mas não recebem nada, e de Charles Dickens, que citou para “afirmar a sua crença (de Mauzó) no amor e na compaixão”.

A musa criativa de Mauzó foi sempre o homem comum goês, retratado tão eloquentemente no romance Karmelin, enquanto os temas das suas obras incluem o género, a casta, a religião e outros aspectos da condição humana. Como parte desses temas, a sua obra investigou a migração, o turismo e a mineração, que até hoje têm relevância em Goa, pois são questões debatidas no domínio público.

Mauzó referiu-se ao percurso literário do concani que, segundo ele, “sofreu golpes tremendos às mãos da sua história”. Isso também é algo que ele experimentou em primeira mão como membro do comité director do Konkani Porjecho Awaz (Voz do Povo Concani) de Goa, pois sofreu várias pauladas da polícia enquanto se debatia para que o concani viesse a ser conferido o estatuto de idioma oficial.

Enquanto as suas realizações literárias o colocaram sob os olhares da opinião pública, a sua paixão pela liberdade de expressão também veio a conferir-lhe grande projecção quando veio à tona uma ameaça à sua vida, após o assassinato da jornalista-activista Gauri Lankesh. Mauzó era então dirigente do Dakshinayan Abhiyan, um movimento lançado contra a discriminação de castas e ataques à intelectualidade e ao racionalismo.

Nada disso teria diminuído o espírito de Mauzó, pois continua a escrever e aparecer regularmente em festivais literários, incluindo o GALF (Festival de artes e literatura de Goa), do qual ele é co-fundador e co-curador.

Nascido em 1944 na Goa portuguesa, ora Estado da Índia, Mauzó fez os seus primeiros estudos, até o primeiro grau, em português, conjuntamente com os estudos primários em marata, tendo depois ido para Bombaim, onde se formou pelo PA Podar of Commerce. Começou a escrever no final da adolescência e continua a fazê-lo, não conhecendo outra ocupação além da loja que dirigia até recentemente.

Era mesmo de esperar que, ao encerrar o seu discurso, Mauzó, ou Bhaiee, como é carinhosamente apelidado esse lutador apaixonado pela liberdade de expressão, se pronunciasse sobre esse direito humano vital. Servindo-se da analogia das rodovias, que ora estão a ser construídas pelo país, afirmou que também há necessidade de “uma rodovia que suavizará o ritmo acelerado da literatura, eliminando obstáculos mentais dos escritores, fortalecendo as pontes de traduções e criando uma atmosfera encorajadora para a liberdade de expressão”.

* Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisboa, No. 23, Serie II, Julho-Agosto de 2023, pp 45-48 https://rb.gy/8qj52

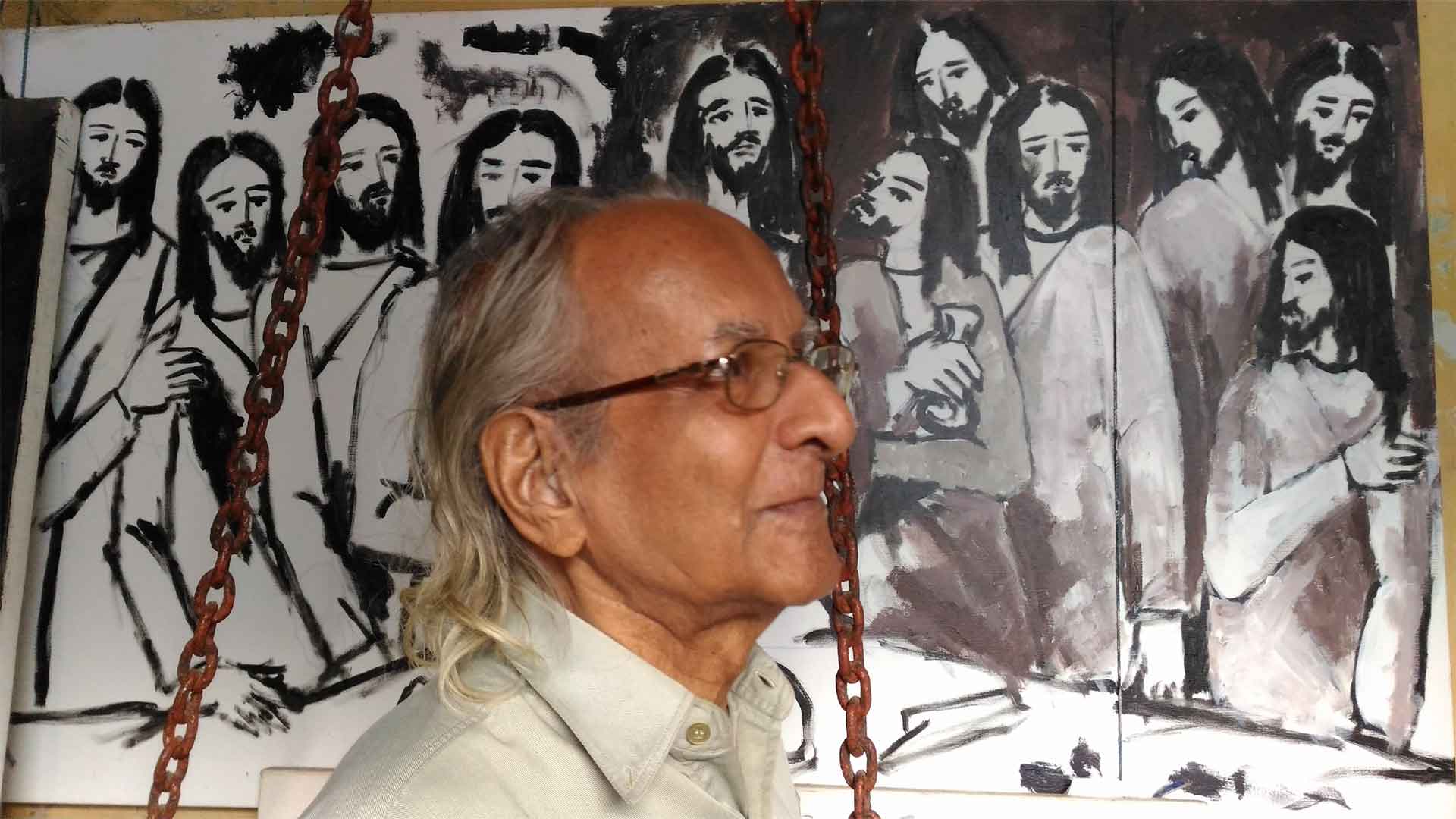

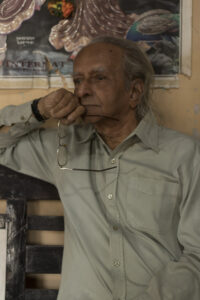

Navelcar, aka Ganesh

On a rainy morning in June [2018], we went up to the village of Pomburpa, taluka of Bardez, on a visit to the well-known Goan painter, stained glass designer and ceramist Vamona Ananta Sinai Navelcar, whose pen name is Ganesh. Despite his grey hair, he was a picture of rare vitality, and in this chat he comes across as enchantingly feisty. He invited us to see the inner patio of his house which doubles as his atelier.

For the original chat show in Portuguese, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rMgblHr5gk4&t=1s

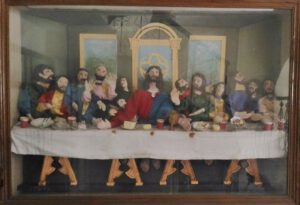

ON: We are face to face with a canvas [Last Supper] that you are working on… I suppose it’s your most recent work...

VN: I started it a week ago and have to deliver it in the next two days...

ON: You work at top speed!

VN: It feels good to work. I have worked on many Last Suppers – more than 30, in Portugal and here…

ON: Do have a penchant for Last Suppers?

VN: Yes, for Christ! At 8 years of age, I used to read the Bible in Konkani. I was surprised to see what a fine figure Christ is! I became more of a Christian ever since, a disciple of Christ indeed. I think I have nothing of Hinduism, nothing, and I belong totally to Christ…

ON: So you have a relationship...

VN: Yes, yes, there is a mystic relationship between me and Christ.

ON: Will this canvas too be signed ‘Ganesh’?

VN: Always Ganesh. None of my paintings bear my name alone. It could bear my name but this is always followed by ‘Ganesh’.

ON: Why ‘Ganesh’?

VN: Ganesh was my elder brother, who died at 16 when I was 8 years old. He was my guide.

ON: Did he inspire you to paint?

VN: My father wouldn’t allow me. He wanted me to be a doctor – like Hindus always do. I used to paint on the reverse of the calendars and would hide them when he came.

ON: Do you still have those calendars?

VN: No longer. After so many years… Well, now they would have been worth a lot.

ON: Indeed. But what was your father’s grouse against painting?

VN: I think the Hindu community holds art in contempt.

ON: Well, the Hindu civilization has great works of art to their credit… Ajanta and Ellora, for example, and so many other places.… Why the contempt, then?

VN: They are materialistic... What money does art fetch you? Medicine does!

ON: If not an artist, what would you have been?

VN: If not an artist today, I would have continued to be an employee of Chowgule’s…. After Matriculation, I began working there; I came across many people, until one day came the inauguration of the Chowgule Mines. Chowgule asked me to draw two portraits: one of him and other of the Governor. I did so. At the inaugural ceremony, the Governor asked the painter’s name; Mr Chowgule said it was one of his employees. I was called. The Governor was Bénard Guedes… the first thing he asked me was if I would like to study Art. If so, I could go to Portugal, but I said I would prefer Sri Lanka or Karachi… He said I should go to Portugal, and I said no. He then gave me a month’s time to decide, and thus I felt compelled to leave for Portugal. I couldn’t speak Portuguese very well then.

Stay in Portugal

ON: Did you complete your Lyceum in Portugal?

VN: There I did the 5th to the 7th Years of Lyceum; I did it in two years.

ON: After the Lyceum, did you move on to the School of Fine Arts? And how long was the course?

VN: It was a five year course. First it was the general course, then the complementary course. And for the admission test, one day as I was practising drawing, the teacher commented: ‘My friend, your drawings are poor. It won’t be a good idea to answer the admission test this year.’ After a week or so, he had a different opinion. My colleagues too were surprised to see a big leap forward from my first drawing. I stood second in the admission test.

ON: How was the Fine Arts course?

VN: Good. But those teachers knew nothing about other arts, the Oriental arts, Chinese and Japanese; and that India is another world, with a different culture. There was, however, a brilliant teacher, architect Frederico Jorge, who said ‘You have an original palette, and bright colours! You have a style of your own. Follow your path.’ Then came the Invasion or Liberation of Goa, or whatever you call it. I was stumped when a Goan asked me a very roguish question. I told him that I had nothing to do with Goa, and that the Goans were to blame for whatever had happened, for they never spoke their mind but remained mum. My scholarship was cancelled; they wanted me to speak out against India. Why would I speak out against India?

ON: After that you went to Africa…

VN: I had to, because the Government had cut off my scholarship, and there, instead of being posted in Lourenço Marques, I was sent to Nampula. I was stuck there for nine years, without a transfer. The Director lamented that despite being the best qualified teacher I was posted up north.

ON: That was politically motivated, wasn’t it?

VN: Yes, but I wasn’t disappointed. Truth always prevails.

ON: Satyameva Jayete [em sânscrito: ‘A verdade sempre triunfa!’].

Teaching career

ON: Were you happy to be a teacher?

VN: Yes. My aim was to understand the student’s technique or to guide them in using their technique, with none of my influence. Or else, they would just be a carbon copy of the teacher…

ON: Well, you let the student enjoy all the freedom!… And how did Africa influence you?

VN: Yes, there is an inadvertent influence of Africa on my paintings.

ON: And what about the people of Africa?

VN: They are a fantastic lot. To me, Africa is the land of Christ…

ON: In what way?

VN: To me, each African face is the face of Christ. Even while in Portugal I didn’t feel any Christian influence as I did in Africa…. Africa is Christ’s Paradise.

ON: That’s a nice expression… Did your style evolve?

VN: Yes, there has been an evolution; and I never repeat myself. What I draw today and tomorrow is completely different.

ON: Do you paint only on canvas?

VN: Really speaking, my specialisation is Stained Glass, a very difficult technique.

ON: Which would you regard as your greatest painting?

VN: None. I’m never happy with my work. I draw but am never happy. I do one and am not happy, another, and still not happy. Some say ‘this work is better than that work’ but I’m never happy with what I’ve done, never! And the day I begin to feel that I’ve done my greatest work it will spell defeat. ‘I am nothing, never shall be anything.’ These words of Pessoa opened the path of my life.

ON: What’s your work schedule? Are you at it every day or only when you feel like it?

VN: I am practically always at work, either drawing or painting.

ON: They say you used to sign your works as ‘Ashok’.

VN: That was in the 1950s and 60s; now it is ‘Ganesh’.

ON: Are there any particular colours that you like best?

VN: Blue, which is spiritual; and red, which represents violence.

On Three Continents

ON: You've been called "an artist of 3 continents". Did you travel a lot?

VN: No; Portugal, England, a bit of France, Italy…

ON: Which artists do you admire?

VN: Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Cezanne, Van Gogh…

ON: Do you think artists are different from others, think differently?

VN: Yes. They have a different perspective.

ON: It’s clear that you are a sincere man, and you like to stick to the truth.

VN: I speak the truth, and that’s why I find myself in the present condition; if not, I would have advanced further.

ON: But your work will be remembered for ever!

VN: Do you think so? My position as an artist is significant. But what has the Government of Goa done for me? Nothing! Today I would have preferred to be in Africa and never to return to Goa, never! It’s terrible. I acknowledge my defeat for having returned to Goa. I have to be frank, right?

ON: Oh yes! What were the other options open to you?

VN: To go to Africa and to stay there.

ON: Are you still in touch with your students?

VN: Yes, with many of them. The Mozambican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Armando Panguene, is a great friend of mine. And his wife was my student at the Lyceum. She is not an artist. She is an Ambassador. A very good lady. She is Armanda, and he is Armando…. When I speak of Mozambique… I get that fever. Wanted to go there…

ON: What was your most memorable experience about Mozambique?

VN: Fraternal friendship.

And as we were about to leave the lovely inner patio of the Navelcar house in Pomburpa, the Master said:

VN: This place is my everything: it is here that I read, sleep, rest…

And we soon got into other details of the Artist…

Navelcar Family

ON: How old is your house?

VN: More than 400 years old.

ON: Is your family from Pomburpa or settled here?

VN: My family hails from Navelim, Divar. They settled here four hundred years ago.

ON: So you were born here, started painting here, and grew up here... And which was your favourite spot?

VN: It was right here.

ON: Well, we find ourselves precisely at the spot of your inspiration…

VN: (Smiles) We would sit here, open these doors and contemplate the rain clouds flying over the house, creating forms that I would relate to the legends of Ramayana and Mahabharata. That influence exists in my works.

ON: Do you like music?

VN: Of course, don’t even talk about it! Western classical music, Mozart, Tchaikovsky…. and the Fado. ‘Aquela janela virada para o mar’ (‘A window with a view of the sea’)… Mourão… and many others… Amália Rodrigues…

ON: And well, here is a window with a view of the river!…

VN: Precisely. I remember Amália. ‘Aquele moreninho’, she would say. When I wasn’t there she would inquire about my whereabouts… She was a simple person, without any airs.

ON: So you knew her personally. Did you meet her when she visited Goa [in 1990]?

VN: Yes; and I offered her a drawing of mine, at the Kala Academy.

ON: So, when did you leave Portugal for Goa?

VN: In 1976. It was a big mistake…I’ve got some friends there. Very good people!

Personal Preferences

ON: What is your favourite food?

VN: Bacalhau [Gomes] de Sá, sausages, too, and beef.

ON: Well, thank you very much for your time, friendship and generosity.

VN: Today is a very significant day. I am here with friends who have deep friendship towards me and towards Art. Hope this will not be your last visit…

ON: Surely not!

VN: I am very grateful to you for your visit.

ON: The pleasure and honour is ours.

VN: And mine too!

(First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, II Series, No. 14, Jan-Feb 2022)

Novos temas, novos rumos

Editorial

Como que num piscar de olhos chegámos ao 10.º número da nossa querida Revista. Queira Deus que a possamos acompanhar durante o tempo que for necessário. Não é só um projecto gratificante; é um trabalho importante – dir-se-ia, premente – nos tempos conturbados em que vivemos. Por isso, vivat, crescat et floreat são os nossos votos.

Nunca foi tão urgente, como o é agora, recuperar o passado para o bem do tempo presente e garantia do futuro. Na verdade, está em jogo a vivência goesa, esse modo de estar tipicamente indo-português. Infelizmente, com a velocidade estonteante em que gira o nosso mundo pessoal e colectivo, pouco tempo nos resta para reflexão, para não falar de acção. Por isso, importa que a nossa agenda seja a de reunir o pessoal e pôr mãos à obra.

O acto de reunir os Goeses dispersos pelo Mundo nunca superou, na nossa Revista, aquilo que presenciamos na presente edição, que tem colaboradores das diásporas luso e anglo-goesas. Temos de tudo: uma lenda de Goa pré-cristã e animista, tal qual narra Celina Velho e Almeida, residente em Goa, até à história duma intriga, pouco conhecida, que se passou em Goa, na época da Segunda Grande Guerra, a qual é contada pelo novo colunista, Armand Rodrigues, que vive no Canadá.

Também pouco conhecida da geração moderna é a história da grande aventura que foi a primeira travessia aérea Lisboa-Goa, relatada aqui com pormenor pelo goês lisboeta Francisco Monteiro. De igual modo, o casal Philomena e Gilbert Lawrence, nossos novos colaboradores, de Nova Iorque, dão uma vista panorâmica da secular ligação entre o povo goês e a Grã-Bretanha, que começou com a breve ocupação de Goa pela tropa inglesa, no fim do século XVIII, e continuou com o recrutamento comercial de goeses por aquele país.

Os nossos leitores irão também deliciar-se com três micro-histórias de Goa, não de somenos importância: José Venâncio Machado, radicado em Portugal, lembra-se com emoção das 153 missas celebradas simultaneamente no largo que estadeia entre a Sé e a Basílica, na Velha Cidade de Goa; Ralph de Sousa relata com verve o vaivém silencioso e apressado de gentes nos transportes fluviais de Goa; e Francisco Monteiro retrata a figura de Paulino Dias, uma das maiores figuras da literatura indo-portuguesa, a quem apelida de “poeta da mitologia hindu”.

Ainda no campo literário, temos Sheela Kolambkar, escritora goesa da língua concani, hoje estabelecida em Bombaim, cujo conto, além de transliterado em caracteres romanos, é também traduzido em português pelo signatário destas linhas; e, mais além, Maureen Álvares, numa entrevista comigo, fala do estado actual da língua e cultura portuguesa no território goês.

Para terminar, no contexto da notícia do lançamento do livro Nacionalidade e Estrangeiros, de Edgar Valles, e a crítica feita por José Filipe Monteiro ao livro Entre dois impérios, de Filipa Lowndes Vicente, volto a realçar que nesta edição da nossa Revista vemos ampliada a nossa visão do Goês como verdadeiro cidadão do Mundo.

Como pano de amostra da nova vitalidade que nos brinda enquanto chegamos à bonita idade de dez edições temos a parceria entre a nossa Revista e The Global Goan, sediada na Oceania. Na verdade, “se mais um mundo houvera, lá chegara”.

É claro que, ao fim e ao cabo, o importante não é chegar algures mas, sim, fazer algo de bom e belo. Eis a Revista da Casa de Goa, a menina dos nossos olhos, que tem o condão de produzir novos temas e novos rumos. Mas não paremos por aí. Olhemos atentamente para os gravíssimos problemas da actualidade goesa e sejamos o fulcro dum plano de acção conjunta da nossa comunidade espalhada pelo mundo, em prol da nossa sempre amada Goa.

(Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 10, Maio-Junho 2021)

Seminário Patriarcal de Rachol salva precioso património

O edifício do Seminário Patriarcal de Rachol da Arquidiocese de Goa, construído pelos jesuítas no século XVII, guarda um precioso património. Em algumas das suas robustas paredes encontram-se pinturas que retratam cenas bíblicas, a vida dos santos, e elementos da doutrina católica. São reproduções de quadros de artistas renascentistas: Rubens, Rafael, Miguel Ângelo e Caravaggio.

Outras pinturas dizem respeito aos Patriarcas da Arquidiocese e a fundadores de ordens religiosas. Vêem-se também obras de Ângelo da Fonseca, conhecido como o “Pai da Arte Cristã Indiana”.

Trata-se de mais de 150 pinturas executadas por artistas locais entre os séculos XVII e XX, em três formas: frescos, telas e óleo sobre madeira.

Por falta de recursos humanos e financeiros, essas pinturas foram deteriorando ao longo dos tempos. A partir do ano de 2017, graças à iniciativa do Reitor Dr. Padre Aleixo Menezes e à boa-vontade de Caterina Goodhart, directora da Escola de Conservação de Quadros e Molduras, de Londres, vários goeses e estrangeiros por ela treinados, ajudaram a restaurar as obras de arte, no âmbito do projecto intitulado “Restauradores sem fronteiras”, iniciado pela profissional londrina.

Até hoje estão restauradas as seguintes pinturas e imagens:

- Retratos dos Patriarcas Mateus de Oliveira Xavier, Teotónio Vieira de Castro, José da Costa Nunes e José de Vieira Alvernaz;

- Tela da autoria do general José Francisco de Assa, a qual retrata o Rei Dom Sebastião, que facultou a construção do Seminário;

- Uma outra, setecentista, representando a levitação de S. Francisco Xavier, no acto de administração da Sagrada Comunhão;

- Retratos de Maria Madalena, Santo António e o Menino Jesus, em estilo flamengo.

As obras do Seminário não só valem em si mas também por serem trabalhos de artistas locais. Reforçam a história e identidade artística do território, além de serem um óptimo meio de transmitir a Fé. Nas palavras do padre Victor Ferrão, professor do mesmo seminário, são elas uma “imagem do céu na Terra” e constituem uma “Bíblia visual” nas paredes.

(in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Fev de 2021)

Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

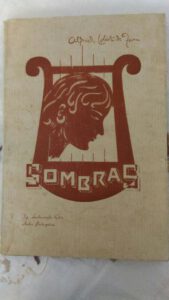

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

Vaz, Montfort and their self-consecrations

Marian dedication stands enriched by the singular contributions made by Joseph Vaz (Goa, 1651 – Sri Lanka, 1711) and Louis de Montfort (France, 1673 – France, 1716).

Vazian Formula

Joseph Vaz expressed his profound love and tender care to the sublime Queen of the Universe and Mother of Fair Love in a memorable document known as the “Deed of Bondage”,[1] which reads as follows:

Be it known to all who see this deed of bondage, the angels, men, and all creatures, that I, Father Joseph Vaz, sell and offer myself as a perpetual slave of the Virgin Mother of God, through a free, spontaneous and perfect gift that in law is said to be irrevocable inter vivos; I give myself and my assets that she, as my true Lady, may dispose of me and of them according to her will; and as I consider myself unworthy of such an honour, I beseech my Guardian Angel and the glorious Patriarch St Joseph, most beloved Spouse of this Sovereign Lady and saint of my name, and other citizens of heaven, to ensure that she includes me in the number of Her slaves. In witness thereof I seal this with my name, and would have liked to seal it with the blood of my heart. Written at the Church of Sancoale, at the foot of the altar of the same Virgin Mary Mother of God, Our Lady of Health, this fifth day of August, Feast of Our Lady of the Snows, one thousand six hundred and seventy-seven. – Joseph Vaz.[2]

In Goa, the consecration has been traditionally looked at as something peculiar to St Joseph Vaz. The original “Deed” is not traceable, but Joseph Vaz’s first published biographer, the Oratorian priest Sebastião do Rego (1699-?), vouches that he read and kissed it several times, in the hope that he would be touched by a spark of the great fire with which it was written.[3] Did the Saint leave the manuscript behind with the Congregation, or with his family, in Goa? Might he have carried it with him to Sri Lanka? Hopefully, it will one day be found among the Oratorian documents.

What might have inspired Joseph Vaz to commit himself thus to our Divine Mother? Was it the influence of a teacher, from among the Jesuits, or more likely from among the Dominicans, who are known to have been great Marian devotees? Did Joseph find motivation in the books of spirituality that he came across in the rich seminary libraries? Further, why did he take the Feast of Our Lady of the Snows for a red-letter day in his life? Was it the fact that she is the patroness of Rome’s most important Marian church popularly called Santa Maria Maggiore?

While answers to those questions may remain conjectural, one thing is sure: what the Apostle of Sri Lanka has bequeathed to humankind is a precious document with a tenor both mystical and direct; it is “a unique deed inter vivos, in which Fr. Joseph Vaz is at once the donor and donation, notary and clerk; and the Blessed Virgin, donee and witness, while the Patriarch St Joseph, Spouse of the Donee and his namesake, his guardian angel and the other citizens of heaven are constituted intercessors before the Donee”.[4] Joseph Vaz is ready, Christ-like, to shed blood in atonement. And far from alienating the reader, the legalese underscores the solemnity of the act.

Montfortian Formula

Coming to Montfort’s act of consecration: it is the grand finale to his Treatise on the True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin.[5] His formula, thrice as long as Vaz’s, reads as follows:

O Eternal and Incarnate Wisdom! O sweetest and most adorable Jesus! True God and true man, only Son of the Eternal Father, and of Mary, always virgin! I adore Thee profoundly in the bosom and splendours of Thy Father during eternity; and I adore Thee also in the virginal bosom of Mary, Thy most worthy Mother, in the time of Thine incarnation.

I give Thee thanks for that Thou hast annihilated Thyself, taking the form of a slave in order to rescue me from the cruel slavery of the devil. I praise and glorify Thee for that Thou hast been pleased to submit Thyself to Mary, Thy holy Mother, in all things, in order to make me Thy faithful slave through her. But, alas! Ungrateful and faithless as I have been, I have not kept the promises which I made so solemnly to Thee in my Baptism; I have not fulfilled my obligations; I do not deserve to be called Thy child, nor yet Thy slave; and as there is nothing in me which does not merit Thine anger and Thy repulse, I dare not come by myself before Thy most holy and august Majesty. It is on this account that I have recourse to the intercession of Thy most holy Mother, whom Thou hast given me for a mediatrix with Thee. It is through her that I hope to obtain of Thee contrition, the pardon of my sins, and the acquisition and preservation of wisdom.

Hail, then, O immaculate Mary, living tabernacle of the Divinity, where the Eternal Wisdom willed to be hidden and to be adored by angels and by men! Hail, O Queen of Heaven and earth, to whose empire everything is subject which is under God. Hail, O sure refuge of sinners, whose mercy fails no one. Hear the desires which I have of the Divine Wisdom; and for that end receive the vows and offerings which in my lowliness I present to thee.

I, N_____, a faithless sinner, renew and ratify today in thy hands the vows of my Baptism; I renounce forever Satan, his pomps and works; and I give myself entirely to Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Wisdom, to carry my cross after Him all the days of my life, and to be more faithful to Him than I have ever been before. In the presence of all the heavenly court I choose thee this day for my Mother and Mistress. I deliver and consecrate to thee, as thy slave, my body and soul, my goods, both interior and exterior, and even the value of all my good actions, past, present and future; leaving to thee the entire and full right of disposing of me, and all that belongs to me, without exception, according to thy good pleasure, for the greater glory of God in time and in eternity.

Receive, O benignant Virgin, this little offering of my slavery, in honour of, and in union with, that subjection which the Eternal Wisdom deigned to have to thy maternity; in homage to the power which both of you have over this poor sinner, and in thanksgiving for the privileges with which the Holy Trinity has favoured thee. I declare that I wish henceforth, as thy true slave, to seek thy honour and to obey thee in all things.

O admirable Mother, present me to thy dear Son as His eternal slave, so that as He has redeemed me by thee, by thee He may receive me! O Mother of mercy, grant me the grace to obtain the true Wisdom of God; and for that end receive me among those whom thou lovest and teachest, whom thou leadest, nourishest and protectest as thy children and thy slaves.

O faithful Virgin, make me in all things so perfect a disciple, imitator and slave of the Incarnate Wisdom, Jesus Christ thy Son, that I may attain, by thine intercession and by thine example, to the fullness of His age on earth and of His glory in Heaven. Amen.

Montfort’s formula begins with an invocation of the Incarnate God. The Christological opening is quickly followed by Marian veneration, in acknowledgment of the Incarnation. Our Lord’s death on the Cross is an act of incomparable nobility, yearning as He did to rescue humanity through His sacrifice; our inspired author stresses that He emptied himself, taking the form of a slave (Phil. 2:7). A self-imposed slavery like this can only be termed a slavery of love.

Montfort points to a divine enslavement that is liberating, as opposed to human liberty that can be enslaving. And what can be better than following Jesus’ example of submitting Himself to His holy Mother? At the heart of the Montfortian formula is the recognition of human unworthiness to stand in the presence of our Lord and God, other than through His Mother’s intercession. The point of resolution comes with the renewal of the baptismal vows; an express renunciation of Satan; and decision to follow Jesus and be faithful to Him.

Appraisal

The two consecration formulas are essentially the same: note the similarity of the terms employed. In addition, Vaz sells himself as a slave while offering himself as a “gift in perpetuity”; he humbly calls upon the angels, men and creatures, to mediate, for is it not perfectly justified to take one’s Guardian Angel into confidence; to appeal to the saint of one’s name; and, as per the communion of saints, invoke their intercession before her.

Vaz’s act is crisp and intimate; Montfort’s, uninhibited and elaborate. St Joseph Vaz’s singular self-offering happened when he was 26 years of age; it is not known when St Louis de Montfort made his, but he included a very brief formula of consecration at the end of his Love of Eternal Wisdom (c. 1703), when he was 30. Vaz embraced the spirituality of St Philip Neri eight years after his consecration; Montfort became a Dominican tertiary in 1710, three years before his Treatise.

Finally, Fr. Joseph Vaz is not known to have ever spoken publicly about his “Deed”, so it may be regarded as a very personal statement. It was for sure a product of his deep conviction; none before him are known to have embraced the slavery of love in Goa,[6] and none from among his confreres are known to have followed his example. On the other hand, not only is Montfort’s Treatise highly elucidative, his consecration formula is an expansive public declaration of what every Catholic ought to strive for; it is a standing invitation to build a profound and intimate union with Christ through Mary.

(Excerpted from my article titled “Two Saints and a Consecration for our Times”, in St Joseph Vaz for All Times, edited by Fr. Aleixo Menezes and published by the Archdiocese of Goa and Daman, 2015, and posted here with minor alterations)

[1] This is sometimes referred to as a “Letter”, in a literal translation of the Portuguese “Carta do Cativeiro”. Whereas “Cativeiro” could be variably translated as captivity, bondage, or slavery; “Carta” would be better translated as “Deed”, and not simply as “Letter”, particularly considering the legal language in which it is couched.

[2] Translated by this author. Cf. Óscar DE NORONHA, Of Divine Bondage: The Epic Life of St Joseph Vaz, (Third Millennium: Panjim, 2014), 25

[3] Sebastião DO REGO, Vida do Venerável Padre José Vaz (Imprensa Nacional: Goa, 19623), 172.

[4] Seráfico MISQUITA, Ven. Padre José Vaz, Apóstolo de Ceilão (Tipografia Rangel: Goa, 1969), 30.

[5] St Louis DE MONTFORT, True Devotion to Mary. Transl. Frederick William Faber. Revised edition. (Montfort Publications: New York, 1967), 227-229.

[6] St Louis de Montfort himself has said that although the true devotion is an easy way, few saints have entered upon it. Cf. James Patrick GAFFNEY, ed., Jesus Living in Mary, op. cit., 231.

A Última Conversa com Percival Noronha

Numa tarde chuvosa (1 de Julho do ano passado), quando de súbito me lembrei do Sr. Percival Noronha[1], não hesitei em terminar a minha sesta dominical. Um distinto cavalheiro – culto, agradável, e que me estimava – daí a dias iria completar a bonita idade de 95 anos… Urgia, pois, falar com o grand old man de Pangim.

Quando liguei para a sua casa, ouvi logo um ‘Estou!’ inconfundível. Na linguagem do Sr. Percival, esse estar era o mesmo que estar disponível! ‘Pode o Óscar vir quando quiser’, disse com a amabilidade que o caracterizava. Estava sempre pronto para um papo, e desta vez seria como nunca dantes: radiodifundida na minha rubrica mensal, Renascença Goa… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRK2PimgTmo) Saí então rumo às Fontaínhas, acompanhado do meu irmão Orlando que trataria das fotos.

Era um prazer ir à residência do Sr. Percival (‘Ajenor’, nº E-426, à Rua Cunha Gonçalves). Também nos cruzámos, por centenas de vezes, em concertos, conferências, exposições de arte, e não menos em casamentos e funerais. Um senhor da velha guarda, era cumpridor dos seus deveres sociais e cívicos. Apesar da nossa diferença etária, a conversa corria como um rio de águas claras, pois o Sr. Percival era não só envolvente mas também apreciador dos méritos dos seus contemporâneos e estimulador dos talentos dos mais novos.

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Diga-se de passagem que eu admirava o seu automóvel, preto, parecendo sempre novo, tal como o seu proprietário. Este, sempre vestido de bush shirt ou camisa safari, percorria os cantos e recantos da cidade, que conhecia como a palma da sua mão. É que Percival e Pangim se pertenciam um ao outro: foi dos melhores cronistas da capital, do seu ethos e do seu ritmo, que descreveu em bela prosa.[2] E fê-lo com autoridade, mesmo porque presenciou nove décadas, ou seja, metade da história dessa urbanização,[3], de forma que hoje se torna difícil imaginar o nosso Pangim sem o Sr. Percival Noronha.

Cargos oficiais

Feitos os estudos liceais na capital, o Sr. Percival Noronha entrou para a administração pública, em 1947. Trabalhou, primeiro, nas Obras Públicas, passando depois para os Serviços da Estatística e Informação. Quando esta foi desagregada, o distinto professor e escritor António dos Mártires Lopes levou-o consigo para os novos Serviços de Turismo e Informação de que este acabava de ser nomeado chefe. O Sr. Percival nunca se esqueceu dos belos tempos do Liceu e do funcionalismo que passou sob a alçada directa desse seu antigo professor liceal: confessava que essa relação fora fundamental em nutrir a sua paixão pela história e cultura.

Quando se deu a mudança do regime politico, em Dezembro de 1961, o Sr. Percival era chefe-adjunto dos Serviços da Informação, reportando ao governador-geral Vassalo e Silva. Em Junho de 1980, a visita do simpático governador coincidiu com as comemorações do 4.º centenário da morte de Luís de Camões em Goa. Vinha a título pessoal, mas nem por isso a visita deixou de suscitar controvérsia.

Decorreu-se o pior da cena no Azad Maidan (‘Largo da Liberdade’), a antiga Praça Afonso de Albuquerque. Aqui, à certa distância, vi o antigo governante a ser interpelado por alegados actos de comissão e omissão do regime português em Goa.[4] O embaraçoso incidente atalhou-o o Sr. Percival Noronha, que, na qualidade de chefe de Protocolo do Território de Goa,[5] estava incumbido de acompanhar o ilustre visitante.

Antes dessa data, com a limitada bagagem de conhecimentos de inglês auferidos no Liceu, e língua essa que logo veio a dominar, o Sr. Percival Noronha ocupou outros cargos importantes na administração indiana. Foi sub-secretário das indústrias, minas, trabalho, saúde e turismo. Entre muitas outras iniciativas suas, os hospitais do Asilo em Mapuçá e o Hospício de Margão passaram a subordinar-se à Direcção de Saúde. Desenvolveu as zonas de Calangute, Colvá, Mayém e Farmagudi, e ideou os desfiles do Carnaval e Xigmó; teve papel preponderante no arruamento Campal-Miramar e na arborização do Parque Infantil; e foi um dos responsáveis pela realização da grande Feira Agrícola em 1970. Ora, possuidor dum raro espírito de autocrítica, não ocultava as faltas que houvera no planeamento e execução dessas suas propostas.

Não admira que o Sr. Percival Noronha tivesse sido um solteirão muito cobiçado. Passou, porém, a vida a cuidar da veneranda mãe, vindo a aposentar-se apenas um ano após a sua morte. Era igualmente dedicado à vida burocrática, passando horas a fio à mesa do gabinete, até para além das horas regulamentares. Um funcionário desse quilate podia facilmente esquecer-se de si próprio, como foi, na verdade, o caso do Sr. Percival Noronha.

Vida de aposentado

Teria sido diferente a sua vida depois de aposentado em 1981? Mudou de actividade, sim, mas o expediente não mudou de volume. Dedicou-se, a tempo inteiro, às matérias por que tinha propensão natural: a arte, a história e a astronomia.

Começou por dotar a sua residência com mobiliário de estilo tipicamente indo-português. Efectuou-se grande parte dessa obra no rés-do-chão do seu prédio, o qual havia sido confiado ao conhecido carpinteiro Zó. Disse-me, em mais de uma ocasião, que gastara nisso quase todas as suas economias. Também é verdade que todo dinheiro lhe era pouco quanto se tratasse de comprar objectos de arte e livros.[6] Assim, a casa se viu transformada em verdadeiro museu-arquivo que deveras honra o histórico bairro das Fontaínhas.

O Sr. Percival não parou por aí: tomou a peito vários assuntos de interesse público. Inspirado pelo alto funcionário (e depois governador) K. T. Satarawala, no ano de 1982 abriu um ramo da Indian Heritage Society em Goa e foi professor convidado da Faculdade de Arquitectura. Exerceu o cargo de secretário daquela organização não-governamental que, em colaboração com a Town and Country Planning Department, preparou um relatório sobre os prédios e sítios de importância arquitectónica no território de Goa. Foi também tesoureiro do INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) em Goa.

Esses organismos continua a desempen har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

Embora o Sr. Percival Noronha fosse indiferente em matéria religiosa, nunca hostilizou a Igreja. Pelo contrário, reconhecendo o papel desta no progresso espiritual e material dos povos, colaborou com as entidades eclesiásticas. Em 1986, quando da visita do Papa João Paulo II, participou entusiasticamente na preparação do evento. E, em 1994, foi membro fundador do Museu de Arte Cristã que ora se acha no Convento de S. Mónica.

Esse goês de gema era um arco-íris de saberes, tratando tanto da arqueologia como da astronomia com a mesma facilidade. Fundou a Association of Friends of Astronomy (AFA)[10], em 1982. Este organismo, além de vir a publicar uma revista mensal, Via Lactea, editada pelo fundador, abriu, em 1990, um observatório astronómico público – o primeiro do seu género na Índia – com o apoio do Departamento de Ciência, Tecnologia e Meio-Ambiente, do Estado de Goa.

O Sr. Percival Noronha viveu uma vida sem artifícios – plain living and high thinking. Foi um líder cultural que criou à sua volta uma pleiade de jovens com decidida propensão pela história, arqueologia, arte e astronomia. Na sua casa, onde funcionavam os dois organismos que criou, recebia jornalistas, pesquisadores e outra gente interessada. Teimava em alertar a geração nova sobre o grave estado de bancarrota civilizacional em que a sua amada Goa estava a descambar. Esses recursos humanos e hábitos salutares sendo o maior legado do Sr. Percival Noronha, tem razão a Fundação Oriente em apelidá-lo de “Um Goês Exemplar”, num livro que publicou em sua homenagem.

Na verdade, é a vida intelectual que o entusiasmava, contribuíndo também para a sua saúde física. A sua roda de amigos da velha data[11] nutria a saudade pelo passado enquanto a geração nova o desafiava com projectos futuristas. Era um desses amicus certus, que tratando-se de algum sem-vergonha, falava, tipicamente, com ironia e sorriso escarninho. Mas não vou sem frizar que a todos desejava o bem, e para uma vida saudável recomendava-lhes uma medida de moog grelado por dia! Antes da prótese da anca, em Abril deste ano, esteve relativamente lúcido e ágil.

Última conversa

96 anos da vida. Dir-se-ia mesmo que o Sr. Percival Noronha teve sete vidas. Nos últimos anos era seu costume, quando adoecesse, anunciar a sua morte e daí a dias estar em pé! Era como que tivesse um sistema imunológico como o do gato persa, de que gostava. Não era motivo para recear, pois, quando ouvi de novo que o Amigo estava em declínio. Tive, porém, empenho em conversar com ele demoradamente.

Às 4,30 da tarde, o Sr. Percival tinha já à mesa o bule de chá e bolachas. Dormira a sesta e estava pronto para uma conversa. A rapariga, às ordens, sentada lá no fundo da sala. E parecia tudo como dantes...

Foi quando notei que o venerando ancião tinha o cabelo despenteado, a barba por fazer, e faltava-lhe a placa de dentes. Nunca o vira assim… Os apetrechos de trabalho estavam lá todos, arrumadinhos, nas estantes e armários, dum lado da sala de jantar, onde costumava passar grande parte do tempo a trabalhar. Também isso não estava como dantes... E reflecti também que desta vez o meu anfitrião que viera ele à janela, como era seu costume, deitando para mim a chave da porta principal… Tudo isso indicava que a sua vida ia afrouxando. Fiquei triste.

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

No entanto, ia falando sobre o seu currículo escolar e profissional; as suas actividades depois de aposentado; sobre Salazar (cuja inteligência e honestidade admirava) e o 18/19 de Dezembro; a administração, portuguesa e indiana; os cursos e conferências que realizou nas universidades da Ásia e Europa; o futura da língua portuguesa em Goa; a cultura goesa e a distorção da sua história; os seus amigos e as pessoas que admirava; e a vida em Pangim: tudo isso, entre muitos outros assuntos, e não necessariamente nessa ordem de ideias.

Nos últimos meses, vi-o, várias vezes, debruçado no peitoril da varanda, qual abencerragem a observar a vida que corria lá fora, e com a cara de quem pensa: Quantum mutatis ab illo… Barbudo, lembrava Abraão, personagem de primordial importância para as comunidades à sua volta. E com aquele cabelo a voar e ele a fitar o firmamento, assemelhava-se à figura de Einstein…

Também lá do alto do Céu ouvirá – no último domingo do mês de Novembro deste ano – a última entrevista que concedeu cá na terra. Foi a minha última conversa com o Sr. Percival Noronha.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] De nome completo, Percival Ivo Vital e Noronha (26.7.1923 –19.8.2019), filho de António José de Noronha, de Loutulim, e de Aurora Vital, de S. Matias.

[2] “Panjim: Princess of the Mandovi” (2002); “Fontaínhas: vivendo com o passado”(2001); “Fontaínhas: the Tale of Panjim’s Latin Quarter” (2003), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015)

[3] A vila de Pangim foi elevada à cidade com a denominação de Nova Goa, por alvará de 22 de Março de 1843, o qual lhe outorgou todos os privilégios de que gozavam as cidades de Portugal Continental.

[4] O incidente impulsionou a minha primeira intervenção jornalística em forma de uma carta ao director dum jornal de Pangim – “Our Honoured Guest”, in The Navhind Times, 12/6/1980.

[5] Na altura, cumulava este cargo com o de director da administração das Obras Públicas.

[6] Doou a sua casa ao sobrinho Francisco Lume Pereira, de Verna, onde Percíval Noronha faleceu, e os livros doou-os à Universidade dos Açores e à Krishnadas Shama Library, de Pangim; e os diapositivos, ao Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino.

[7] “Christian Art in Goa” (1993); “Indo-Portuguese Furniture and its Evolution” (2000); “Priceless Christian Art” (2004), e “Goan Artisans” (2008), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[8] “Levantamento arqueológico da Velha Goa e tentativas para a sua conservação” (1989); “Old Goa in the context of Indian heritage”(1997); “Um passeio pela Velha Cidade de Goa”(1999); “A Capela de Nossa Senhora do Monte, em Velha Goa” (2001), ), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[9] Recebeu ao todo 16 galardões de proveniência vária.

[10] http://afagoa.org/about_us.html

[11] Entre outros, António dos Mártires Lopes, Aleixo Manuel da Costa, Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes, Alcina dos Mártires Lopes, Artur Teodoro de Matos, Luís Filipe Thomaz, Teotónio de Souza, Rafael Viegas, Nandakumar Kamat, Satish Naik.

[12] Tradition and Modernity in Eighteenth-Century Goa (Manohar, New Delhi & Centro de HIstória de Além-Mar, Lisboa, 2006)

[13] Old Goa: A Complete Guide (Panjim: Third Millennium, 2004)

[14] Castilho de Noronha: por Deus e pelo País (Panjim, Third Millennium, 2018)

Fotos de Orlando de Noronha, com excepção da da condecoração (e-cultura.pt) e da do lançamento do livro (Fundação Oriente)

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série, Número 1, Maio/Dezembro de 2019 https://issuu.com/jmm47/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n1_-_maio-dez_

What was the Inquisition? - 2

Considering that the secular mind is quick to make the very word ‘Inquisition’ look odious, is it not its bounden duty to also check its own moral standards? Can our generation be sure that future generations will not be as uncharitable towards us as we have been vis-à-vis the Inquisition?

It is only fair that an institution or an event be looked at in the light of its age. Hence, before we draw up a balance sheet of the Inquisition, let’s look at some of its features. When the medieval institution was eventually replicated in many countries, there were inevitable changes in its set-up from place to place; however, its nature and procedures remained essentially the same, as outlined below.

Features of the tribunal

a) Nature: Ecclesiastical courts dealt regularly with disputes concerning discipline, administration of the church, and spiritual matters. But in places where heretics were strongly entrenched, the Church set up the inquisition as a special court with permanent judges or inquisitors. It was a formal court with rules of canonical procedure; its judges executed doctrinal functions in the name of the Pope. Thus, the Congregation of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition, or Holy Office, established in Rome in 1542 was historically continuous with the episcopal courts of earlier times and with the ones set up later. In the age of liberalism the powers of the tribunal came to be limited by local control and resistance.

At establishment of the inquisition in the thirteenth century, members of the Dominican and Franciscan Religious Orders, newly set up then, were offered the inquisitorial task, in view of their superior theological training. There is no reason to believe that those judges were in any way intellectually and morally inferior to their counterparts in modern judicial tribunals. Some inquisitors were no doubt harsh; but their lot has to be judged as a whole. Some errant inquisitors were even deposed and then incarcerated for life.

b) Procedure: Any new inquisition tribunal began by declaring a “period of grace” for the local Catholics. When summoned before the inquisitor, those who confessed their faults of their own accord were given a mild penance. When suspects did not report, and meanwhile much evidence had been obtained against them through the parish priest or lay persons, such suspects were cited before the judges and the trial began. If they made a clean breast of their faults, the affair was soon concluded to the advantage of the accused. If they entered denial even after swearing on the Gospels, the evidence already collected was put forward.

It is not known for sure whether the accused were imprisoned throughout the period of judicial inquiry. It seems quite unlikely that they would be, considering the burden on the exchequer. Nor was it even necessary, for freedom of movement was conditional: the suspect had to promise under oath to be available for inquiry and to accept the inquisitor’s sentence with good grace. Obviously, the judge would be favourably inclined if the suspect kept the oath. Besides, the inquisitor could grant bail or have reliable bondsmen to stand surety.

Medieval courts used torture as means of eliciting the truth. The inquisition adopted the method a few decades after its inception – and it is still part of judicial inquiry in many countries. However, torture was permitted only after all other expedients (counselling, coaxing, instilling fear of death, and even confinement) had been exhausted, or if the accused was inexact in his statements and virtually convicted by manifold and weighty proofs.

Torture was to be applied only at any one stage of the inquiry and without causing loss of life or limb. Many a judge skipped this procedure, considering it deceptive and ineffectual, but there were others who depended on it and even exceeded their authority. This made the inquisitor and other officials liable for suspension. Sometimes pressure was exerted in this regard by the civil authorities, overshadowing the ecclesiastical purposes of the inquisition.

While it was mandatory to have depositions by at least two witnesses, some judges would demand more. The Church initially believed that testimony of an "infamous" person was worthless before the courts, but later began to accept their evidence at nearly full value in trials concerning the Faith. Similarly, while at first it was a rule to withhold the names of the witnesses from the accused person, by and by naming witnesses was mandatory, but no personal confrontation of witnesses or any cross-examination ever allowed. Needless to say, false witnesses were severely punished.

It is a pity that witnesses hesitated to appear for the defence, fearing that they would be suspected of heresy. Similarly, the defendant rarely secured legal advisers, so those accused were obliged to respond personally to the main points of a charge. If thrown behind bars, they were given pen and paper for the purpose but no books to read or refer to. Years later, the law provided for heretics to be granted a legal adviser who was beyond suspicion – upright, skilled in civil and canon law, and zealous for the faith.

The accused could let the judge know his enemies; and should these turn out to be the accusers in the case, the charges would be quashed.

c) Bishop and the councils: These were introduced as a system of checks and balances, to save the inquisition tribunals from arbitrariness and caprice. The accused were also referred to the bishop who together with the inquisitor and a number of boni viri – upright and experienced men well versed in theology and canon law – would be summoned for the purpose of deciding on two questions: whether guilt lay at hand and what punishment was to be inflicted.

To preclude personal considerations, cases would be submitted to the council without naming any names. The role of the good men was advisory in nature, yet the final ruling was usually in accordance with their views.

The inquisitors were also assisted by a consilium permanens, or standing council, composed of other sworn judges.

d) Revision: When a decision was revised, it was in the direction of clemency.

e) Imprisonment: If the prison conditions were not up to the mark, the local bishop was supposed to look into the matter. If necessary, he would have meals provided to the prisoner from the proceeds of the confiscated property belonging to the latter.

f) Right to Appeal: The accused could reject a judge if he sensed some prejudice and, at any stage of the trial, appeal to a higher tribunal in the country’s capital or in Rome. The documents of the case would be dispatched there under seal. People would not do so as a matter of course, considering the time and money that it entailed; but sometimes it was considered worth the effort.