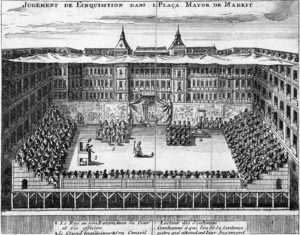

What was the Inquisition? – 1

The Inquisition has long been made to look monstrous. The Essential Catholic Survival Guide reckons that “to non-Catholics it is a scandal; to Catholics, an embarrassment; to both, a confusion.” Indeed, our generation shies away from its memory or, if caught on the back foot, quickly turns apologetic. It is as though we are under a spell, and this is the handiwork of those inimical to the Catholic Church or at least unaware of the real functioning of the court that was the Inquisition.

The point here is not to whitewash a much maligned institution but to understand its nature. We are before a formal tribunal, not a mere people’s court; that this court had well established procedures, similar to modern courts in many ways and, obviously, following contemporaneous standards of justice, however alien they may seem to our generation. And given the lack of documentation, it is unreasonable to depend on statistics alone to make up our minds about that institution.

Definitions

‘Inquisition’ and ‘Heresy’ are two terms that call for special attention. The first one, from the Latin inquirere, meaning “to inquire”, refers to questioning. Roman law provided for an inquisitorial procedure by magistrates investigating crimes in the absence of formal charges being brought to their attention. After the Empire converted to Christianity in the fourth century, the procedure was employed by emperors from Constantine onwards to investigate heresy and related cases. It behoved the State to uproot this crime which always had socio-political implications; it was only in the second millennium that the Pope intervened, to rein in excesses, by setting up a formal tribunal, though not fully successfully.

Heresy isn’t the same thing as incredulity, schism, apostasy or some such sin against the faith. The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines heresy as “the obstinate post-baptismal denial of some truth that must be believed with divine and Catholic faith; or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same.” The doubt or denial involved in heresy concerns a matter that has been revealed by God and solemnly defined by the Church, be it the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation, the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, Papal Infallibility, the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary.

It was the task of the Inquisition to ascertain whether a person was guilty of propagating a heresy. Mere holding of wrong notions of Catholic doctrine privately did not attract sanctions from the court. Only a person found to be spreading those views came under the scanner of the Inquisition; and only refusing to be corrected would be considered heretics.

The Inquisition judged Christians; it was thus no torture plan to convert people to Christianity, as it is made out to be. Neither was it an instrument of evangelisation nor were there ever any provisions under Church law for the use of force to convert a person to the faith. The Inquisition aimed primarily to try and reform the accused and win them back to the faith. However, as heresy was an offence under the law, the tribunal, like a parent punishing an intractable child, would have hardened offenders penalised, so as to safeguard the common good. In those days, when Church and State were united, like soul and body, the law holistically catered to the citizens’ spiritual and material welfare. It goes without saying that very often the State overruled the Church, disparaging the spiritual and reformatory aspect and exalting the material and punitive side.

Historical development

Like Moses who was anguished by his people’s worship of the Golden Calf, the Christian Apostles too were deeply concerned about guarding and transmitting the deposit of the Faith undefiled. Unfortunately, not only the early days of Christianity, the whole of the first millennium was riddled with heretical doctrines: the Circumcision heresy (1st c.); Gnosticism (1st-2nd cs.); Montanism (late 2nd c.); Sabellianism (early 3rd c.); Arianism (4th c.); Pelagianism and Semi-Pelagianism (5th c.); Nestorianism (5th c.); Monophysitism (5th c.); Iconoclasm (7th-8th cs.) and Catharism (11th c.). The Church authorities suffered the consequences of those heresies but, rather than opting for the Old Covenant penalties of death or scourging, simply excommunicated the heretic.

On the other hand, the imperial successors of Constantine, who regarded themselves as masters of the temporal and material conditions of the Church, were persuaded that it was their first concern to protect the State religion. Heresies generated anarchy, so penal edicts (confiscation of property and death) were issued regularly against heretics. A law of the year 407 asserts for the first time that heresies ought to be equated with high treason. For their part, the church authorities in the Christianised states of the Roman Empire refused to invoke the civil power against the heretics.

Ironically, it was the heretics who appealed to the civil power for protection against the Church, and before long complained bitterly of administrative cruelty. At this point, Bishop St Optatus of Mileve defended the civil authority, thus championing for the first time a decisive cooperation of the State in religious questions and its right to inflict death on heretics. This matter wasn’t settled unequivocally given that several ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel. St Augustine was one such bishop who tried to lead back the erring by means of instruction. However, he changed his views, perhaps moved by the incredible excesses perpetrated by the heretics. Yet, it was the desire of the bishop of Hippo to correct them, not put them to death; he wanted the triumph of ecclesiastical discipline, not the death penalties that they deserved.

Meanwhile, as often as the social welfare required it, Christian rulers sought to stem the evil with appropriate measures. In an attempt to save the kingdom and save souls, even distinguished citizens, ecclesiastical and lay, were burnt at the stake. Often there were outbursts of Christian popular sentiment against dangerous sectaries. Sometimes the people blamed the clerical softness in pursuing heretics and so took the law into their hands. Kings and bishops responded by condemning heretics to the stake to prevent the spread of what they called “the heretical leprosy”.

According to the Catholic Encyclopaedia, a definitive strategy came about after Frederick Barbarossa, the powerful king of Germany and Sicily, and Pope Alexander III reached an accord reconciling their respective powers in the Peace of Venice in 1177. This was reaffirmed at the Lateran Council of 1179. In 1184, Pope Lucius III issued the decretal Ad abolendam (‘To abolish diverse malignant heresies’) which some have called the “founding charter of the Inquisition”. It commanded bishops to take an active role in identifying and prosecuting heresy in their jurisdictions. Heretics would suffer excommunication from the Church and be handed over to the civil power to be punished according to the provisions of the common law.

Accordingly, the first Inquisition tribunal was established in southern France in 1184. While death was still not on the cards, punishment was limited to exile, expropriation, destruction of the culprits dwelling, infamy, debarment from public office, and the like. The explicit identification of heresy with treason and its prosecution according to the norms of Roman law was formalised in 1199 by Pope Innocent III. At the Lateran Council of 1215, a relative service was done to the heretics by the introduction of regular canonical procedure to abrogate the arbitrariness, passion and injustice of the civil courts and from the penal codes in Spain, France and Germany.

New Challenges

Although medieval Europe was a society of Catholic kingdoms, adherents of other religions, particularly Judaism and Islam, also lived there. In the first few decades of the thirteenth century, Christian Europe was so endangered by heresy that a formal ecclesiastical tribunal under direct papal jurisdiction became a social, religious and political necessity. Pope Gregory IX established the so-called Monastic Inquisition by his Bulls of 13, 20, and 22 April 1233, appointing Dominican monks as the official inquisitors for all dioceses of France. The Inquisition had jurisdiction only over the Catholic populace; non-Catholics would be hauled up only if found to be perverting Catholic mores. At a time when the people had higher regard for the soul than for the body, heresies were spiritual terrorism to be tackled with vehemence, just as we do against acts of physical violence today.

Broadly speaking, the new tribunals of the Inquisition established in Europe and Asia faced many challenges, some of which are listed below:

a) Catharism (13th century)

These sects were a social menace right from the Byzantine period. They were treated with severity, yet they poured over all of Western Europe. A mix of religions reworked with Christian terminology, Catharism was an umbrella for multiple sects, one of the largest being the Albigensians. By and large, they were not only hostile to the Mass, the sacraments, the ecclesiastical hierarchy and organization, and to the government; their views were fatal to the continuance of human society as they forbade marriage and made a duty of suicide. It was only natural that both Christian and non-Christian custodians of the existing order in Europe should adopt repressive measures against their aberrant teachings.

b) Conversos (15th century)

Pope Sixtus IV empowered Ferdinand and Isabella to set up the Inquisition in Spain in the year 1478, to confront the conversos, pseudo-converts from Judaism (Marranos) and from Islam (Mouriscos). The tribunal turned very fierce even by the standards of the time, so much so that the Pope made efforts to limit the powers of the inquisitors but to hardly any avail. In 1483, a Grand Inquisitor and Supreme Council was appointed to supervise local inquisitorial tribunals, including the later ones in Mexico and Peru. The first Grand Inquisitor, the Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, also exceeded his powers.

c) Protestantism (16th century)

At the turn of the sixteenth century, Europe found itself divided into two ideological blocs: one Catholic and obedient to the Pope; the other, Protestant and opposed to the Pope. After Luther, Calvin and Henry VIII parted ways with the Catholic Church, each began spreading theological ideas that were in conflict with the teachings of the Catholic Church. Their movements began to gain ground in various principalities and kingdoms of northern Europe.

The great apostasy or disaffiliation from the Catholic Church prompted Pope Paul III to establish the Sacra Congregatio Romanae et Universalis Inquisitionis seu Sancti Officii (Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, or the Holy Office), in 1542. It consisted of a commission of six cardinals. They were at once the final court of appeal for trials concerning the Faith and the court of first instance for cases reserved to the Pope. It inaugurated an era of institutionalised inquisitions. Succeeding popes made further provisions for the procedure and competency of the Inquisition of which Pope Sixtus V is regarded as the reorganizer.

In that same year, the Pope made known the first list of books prohibited for their doctrinal content or criticism of the Catholic Church. A more comprehensive Index of Prohibited Authors and Books was brought out after the Council of Trent (1545-63). Later, a separate though related Congregation of the Index updated the list.

d) Paganism (16th century onwards)

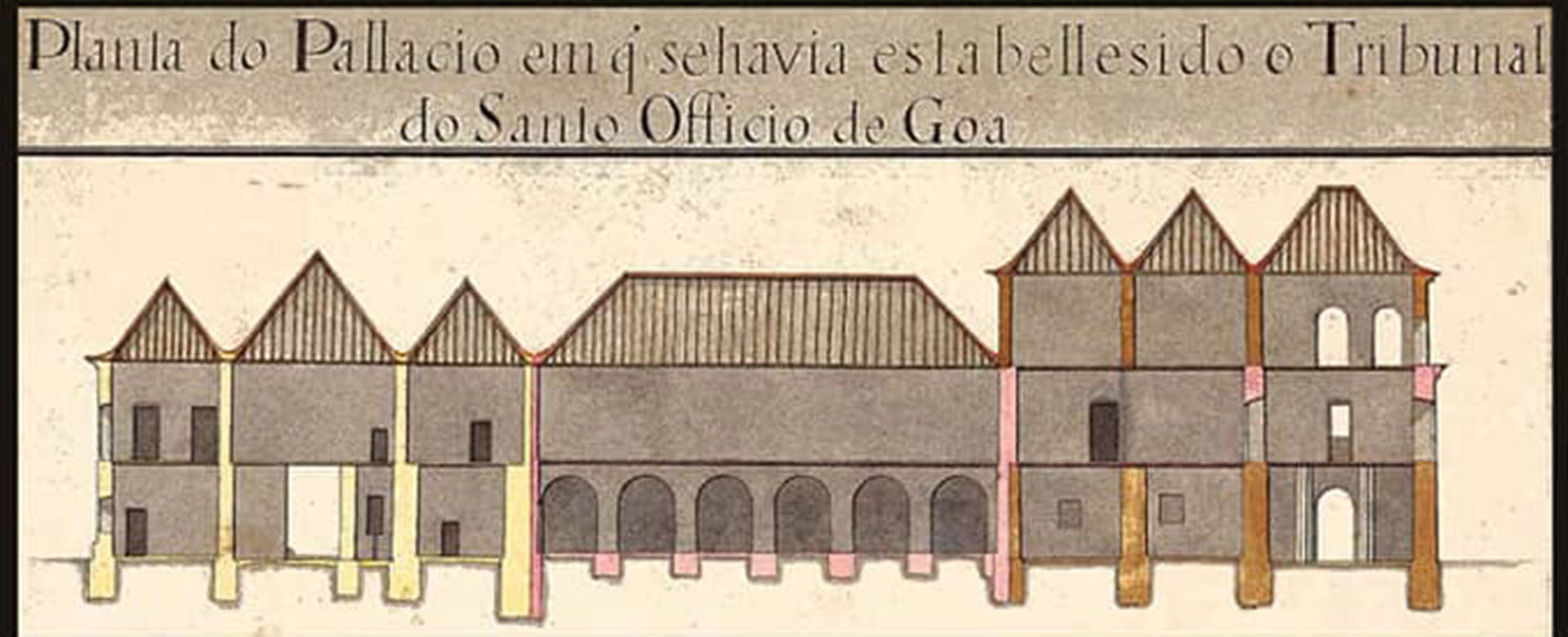

This is an umbrella term for beliefs held by polytheistic religions. It applied especially to the religious beliefs of the natives of the colonies held by Portugal and Spain in Asia, Africa and Latin America. King João III of Portugal applied to the Pope for an independent Portuguese Inquisition to deal specifically with threats posed by crypto-Jews in his country. A branch of the tribunal was set up in the city of Goa in 1560 to handle cases relating to the ethnic Portuguese in India and to neo-converts to Catholicism (Jews, Hindus and Muslims) relapsing into their former religions or practising them side by side with Catholicism.

e) Heterodoxy (18th century onwards)

This refers to views that differ from right belief or purity of the Faith, or say, orthodox views. ‘Right belief’ is not subjective, as resting on personal knowledge and convictions, but that which is in accordance with the teaching and direction of an absolute extrinsic authority.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Eventually, Rationalism, or the use of human reason or understanding as the sole source and final test of all truth, began to form the basis of intellectual and scientific activity. It seemed to hold out a promise of dramatic improvement in human life. These tendencies finally led towards religious disbelief, evident in such modes of thought as atheism, agnosticism, materialism, naturalism, pantheism, scepticism, and the like.

New Winds

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the stage was set for republican revolts against European monarchies, beginning in Sicily and spreading to France, Germany, Italy, and the Austrian Empire. They ended in failure, repression and widespread disillusionment among liberals.

Nonetheless, winds of liberalism kept blowing hard, unsettling the traditional ways of thinking. Reason continued to score points against faith and displace it across Europe. In fact, religious beliefs began to be equated with blind faith; so faith looked weird when juxtaposed with free private judgement. The view that orthodoxy should be maintained at all cost began to be looked upon with suspicion.

With religion itself relegated to the background, how could a mere institution that stood staunchly for preserving the deposit of the Faith be welcome? Here was a propitious moment for dissenters to quickly and impudently go about their business of discrediting the Catholic Church. The process that had started with the Protestant Revolution gained steam with the French Revolution. It is no wonder, then, that we moderns experience difficulty in grasping the rationale of the Inquisition. The punishments meted out by the tribunal for heresy seem exaggerated, not to say irrational and misplaced.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

How are we to explain the Inquisition in the light of its own period? To do justice to the topic, we need to first have a look at the broad features of the tribunal of the Inquisition.

(To be continued… Part 2)

A Wobbly Webinar on the Goa Inquisition

A few hours ago I watched a webinar on the Goa Inquisition, subtitled “untold atrocities by St Francis Xavier and missionaries”. It was flawed from the very beginning, for although St Francis Xavier had wanted the tribunal to put an end to profligacy in the city of Goa, he died in 1552, eight years before it was established. Nor did the panelists accuse any other missionary, in the course of the ninety-minute long proceedings.

The session began with a demand that the horrors, atrocities, brutalities, cruelties, what have you, of the Goa Inquisition be made known to the world, and a museum established at the earliest. You can be sure the webinar was hardly an academic exercise, not just because three out of the four speakers there are politically affiliated, but because the so-called “online exhibition” was exhibitionist, marked by cheap rhetoric and wild exaggeration.

The only academic present on the panel quickly rattled off dates. His only argument was that the Catholics of today are not to be blamed for what happened centuries ago. He should have also brought out the nature of the tribunal; he didn't do so, yet he didn't fail to make some sweeping statements. The professor presented no counter-argument to the macabre theory developed by the organisers of the webinar; but that’s because the other speakers did not put forth any argument in the first place. They were in plain accusation mode; it was all sound and fury, signifying nothing.

When dealing with such a sensitive historical issue, one would expect at least one honest and fair-minded panelist to state the meaning, nature and functions of that much maligned ecclesiastical court of law, and let the listeners make up their minds. On the contrary, the speakers were not only highly critical, they issued summary judgements – something that the very tribunal under attack never did! The tribunal sure had shortcomings but it did follow well laid out procedures and give the accused the right to defend themselves.

Was it that the panelists did not have enough time to go into the main aspects of the Inquisition? Not at all. Going by the organisers’ track record, one would not expect them to give evidence, weigh each word as they spoke, and see both sides of the issue... And how could one expect them to lay their cards on the table? That would in fact have knocked the wind out of their sails. That would have taken the sting out of their agenda.

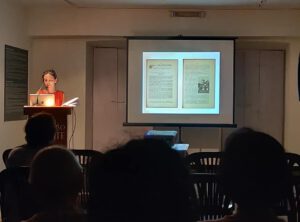

All about Amor

Maria do Carmo Piçarra’s talk at Fundação Oriente, Panjim, was titled “Behind the Portrait of Antunes Amor, Educator and Pioneer of Cinema in Goa”. A researcher at Instituto de Comunicação da Nova (ICNOVA), Lisbon; assistant professor at University of the Arts, London (UAL); and a Fundação Oriente scholar, Piçarra holds a doctorate in Communication Sciences. She is a film programmer; author of several publications, among them Azuis Ultramarinos. Propaganda colonial e censura no cinema do Estado Novo (2015) and Salazar vai ao cinema (2006, 2011), and principal editor of (Re)Imagining African Independence. Film, Visual Arts and the Fall of the Portuguese Empire (2017).

Piçarra contextualised a painting titled “Mr. Amor. The Portuguese Agent” (1917) from the Trindade Collection on permanent display. That striking piece of art by the Bombay-based Goan painter António Xavier Trindade (1870-1935) was gifted to the Foundation by Dr Marcella Sirhandi, a friend and biographer of the artist.

Piçarra spoke of Amor’s cinematographic forays in Macau, where he screened his first amateur movie. She also mentioned the films he made about school life, history, and so on, while in Goa. A strong defender of the pedagogical and propagandist uses of cinema, Amor had several of his films shown in local halls.

The precious little I already knew of Manuel Antunes Amor (1881-1940) I had heard from my father a quarter of a century ago; I was now surprised to see him again! Trained in Germany in the early twentieth century, Amor (‘Love’, in Portuguese) was a self-opinionated gentleman whose tenures as primary school inspector in Goa (1916, 1922) were mired in controversy.

Finally, Piçarra's remark that Amor was particularly suspicious of lawyers reminded me of that high-profile polemic he had with Joaquim de Araújo Mascarenhas (1886-1946), a Goan legal eagle who doubled as Portuguese language teacher at Liceu Nacional de Nova Goa. A lethal combination it proved to be.

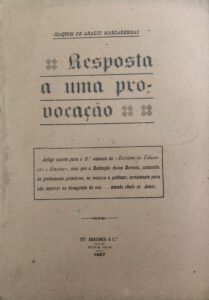

An article titled “O ensino primário e a incúria do Estado” ('Primary school education and State neglect') that Araújo Mascarenhas wrote for the maiden issue of the monthly Boletim de Educação e Ensino (April 1927) made Amor see red. He wrote a censorious rejoinder, “Sem autoridade nem razão” ('Devoid of authority or reason'), in the very next edition.

Araújo Mascarenhas dashed off a point-by-point rebuttal. The Boletim’s editorial board that comprised primary school teachers declined to publish it, possibly fearing the inspector's wrath. It led the redoubtable polemist to bring out a volume titled Resposta a uma provocação ('In Response to a Provocation').

Sadly, the Boletim folded up in August that year, but not before the long series of events had vitiated the atmosphere. No wonder the very gifted Mr Amor was someone many Goans loved to hate.

Why the Inquisition in Goa

At Instituto Camões, Panjim, Professor José Pedro Paiva of the University of Coimbra provided a lucid rationale for the establishment of the Tribunal of the Inquisition in Goa (1560-1812). His talk was titled "Reasons for the Founding of the Goa Inquisition in 1560". He stated, among other things, that even prior to the arrival of St Francis Xavier the Religious had endeavoured to establish the Tribunal in Goa.

For my part, convinced that no serious student of history should depend exclusively on Charles Gabriel Dellon's much-quoted account titled Relation de l'Inquisition de Goa (1687) and Bombay-based A. K. Priolkar's expedient interpretations of the Frenchman's allegations, I asked the erudite Professor where one would find fresh archival sources to counter their claims. He pointed to the Portuguese and Brazilian archives.

Without a doubt, the Tribunal, like every human enterprise, had its shortcomings; but having said that, by no means do Dellon and Priolkar deserve a clean chit. While the testimony of the former, who was tried and incarcerated by the Tribunal, is largely suspect, the latter's narrative fails to contextualize the institution, and his vitriolic language hardly behoves a researcher. It is curious to note that his work appeared in the year 1961, a watershed in the history of Goa and Portugal.

It is a pity that there has hardly been any comprehensive study of the Goa Inquisition, particularly in the English language. And alas, just as a big lie told frequently enough is finally believed, unsuspecting readers have found themselves trapped in a web of lies regarding the nature and purpose of the Inquisition. It is heartening that a younger crop of researchers has been shedding fresh light on the subject and overturning previous findings or misplaced conclusions.

Meanwhile, as the matter in question often boils down to the number of deaths at the stake, I was keen to know details of the same. The exact figure will never be known, since the relevant papers are unavailable, for reasons too complex to mention here. However, Professor Paiva authoritatively stated that, based on the lists of names available in Lisbon, the number of trials held in Goa, over a period of 250 years (1560-1812), are reckoned at 14,000 and the convictions at 800, the average thus being 3.2 deaths per annum.

Comparisons may be odious, but can we overlook the odious crime of human sacrifice perpetrated in Indian society outside the borders of Goa during that same historical period? Some of them had religious sanction, others were committed arbitrarily, but none gave any scope for self-defence or mercy. Similarly, who can deny that the number of convictions by criminal courts far exceeded the inquisition tribunal's annual average of convictions?

Finally, those numbers pale by comparison to the political and other inquisitions at work in the twenty-first century, many of which - please note - do not have even the semblance of a tribunal or a fair trial. Hence, a sense of history and fair play are a must to understand the rationale behind the Inquisition tribunal set up in Goa way back in the sixteenth century.

Tribute to my Father

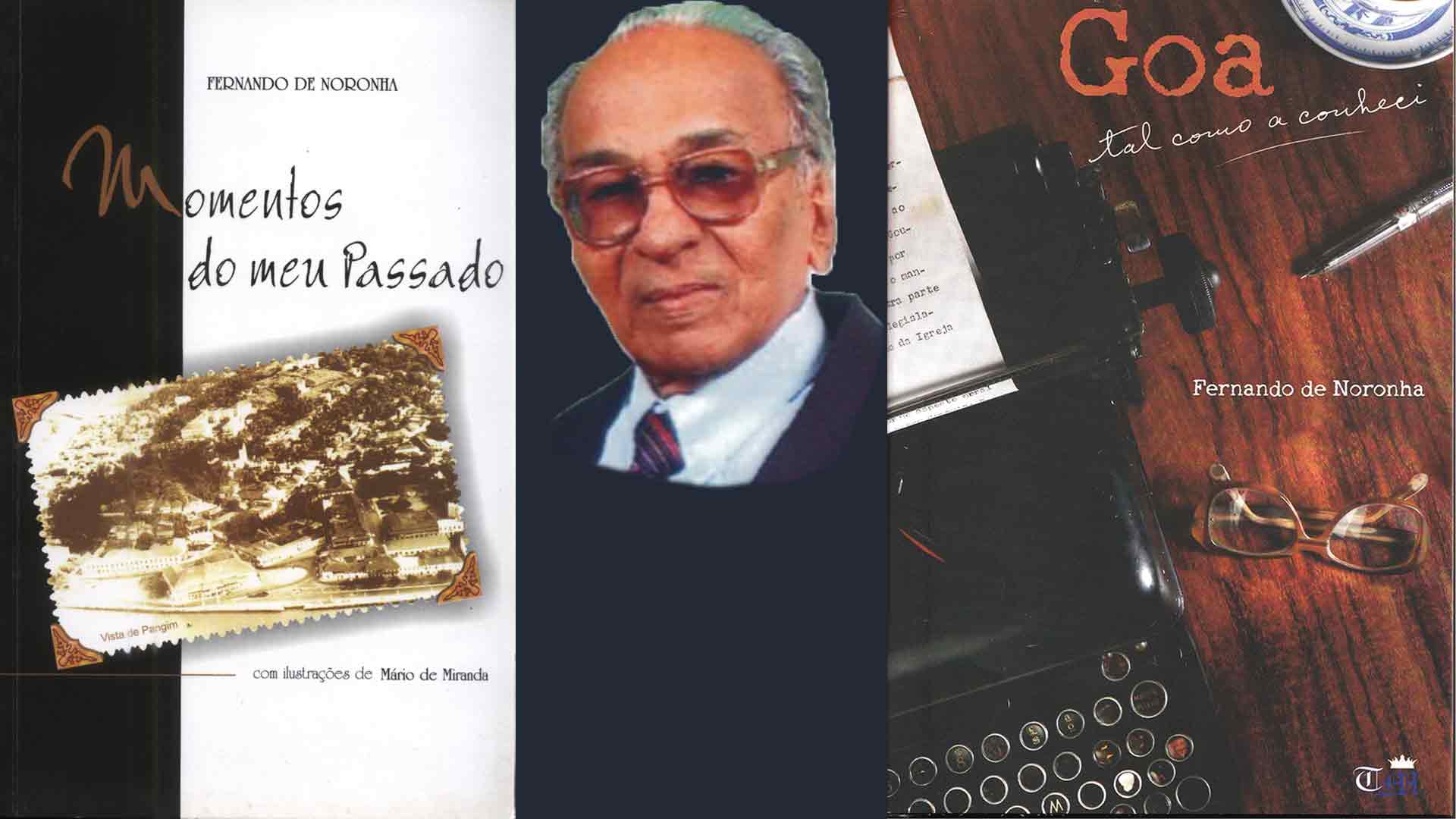

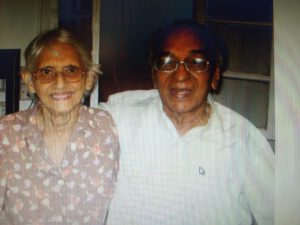

Early this month the social media was abuzz, in anticipation of the twenty-twenties; as for me, I was on a solo trip back to nineteen-twenty. As a child, this year had the earmarks of a happy milestone for me, yet it triggered anxiety for the future. My childhood was a shrine of happy pictures, yet the thought of that golden marker fading into the horizon would fill me with sadness. Why? Because while a young me was looking ahead to what would be, my father Fernando was already looking back upon what had been….

My lone source of anxiety for the future was that I was the eldest child, born in Papa’s forty-fourth year. I knew not how long I would have him: it was a worry I kept to myself so as not to dishearten him. But then, hardly anything disheartened him; he kept pace with his children and even his grandchildren’s progress, and enjoyed the sleep of the just. When he passed on, at 91, he was a grandfather to fifteen. His abiding trust in God was the secret of his longevity – as well as a salutary lesson on the futility of anxiety.

In my naiveté, 1920 still felt charming; as I grew older, I found Papa’s idealism, independence and integrity appealing. I looked up to him, especially because his life hadn’t been easy: the ‘roaring twenties’ of the West had played out quite differently in Portugal and Goa. Following a decade of political turbulence and galloping inflation, the country stabilised and the escudo roared upon the rise of Salazar the economist. Convinced that he was a man with ‘the right intention’, my father held him in esteem for his intellect and honesty – the antithesis of leaders in sham democracies.

After God, it was Goa uppermost in Papa’s mind. The Mass and the Bible alongside spiritual classics were his daily fare. To compensate for arid bureaucratic matters, he put his faith in reading, writing, teaching and music. Even while he took delight in the Romantics Eça, Camilo and Ramalho, he recommended some excellent Goan writers. Until his last breath he lapped up the masters of the Portuguese language, not forgetting two of our very own Goan purists, Costa Álvares and Filinto C. Dias.

One gets a bird’s eye view of Papa’s outlook from his first book, Momentos do meu Passado (Moments from my Past). Much of it is what he used to recount animatedly at the dinner table or talk over with relatives and friends. He obliged us by writing this slim volume comprising ‘figures, facts and facetiae’: pen sketches of over thirty personalities from the Goan social and political milieu; some little-known facts of contemporary history; and a host of anecdotes dating back to his Lyceum days. In his words, he wished ‘to quench saudades of a not so distant past, when one lived in a happy and carefree manner unique to Goa.’

It took me some time to appreciate Papa’s simple and straightforward nature. And noticing how people would often agree but also end up severing ties with him, I learnt that truth can indeed puzzle, confound, hurt… Papa’s intermittent observations on public affairs are lost in the thicket of Heraldo and A Vida for, whilst a bureaucrat in two key departments during the Portuguese regime, he used pen names of which he kept no record. In 1967, his commitment to ferry people to the booths on the occasion of the Opinion Poll (16 January, his birthday and feast of St Joseph Vaz) fetched him a resounding office memo.

It warms the cockles of our hearts to see that Papa’s second book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), contains the essence of his views on people, events and ideas. Covering as he did twentieth-century Goa’s political and administrative affairs, society, culture, and religion, in a total of eighteen chapters, this offering is a testimony of love for the land and the people. It is also a tribute to the Portuguese language that was so dear to him. After opting to retire from public service, he taught that idiom at a city college and co-founded a weekly, A Voz de Goa. At Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church he prayed in that ‘language of the angels’ and put together a choir at Sunday mass.

Music was high up on his agenda ever since his father purchased a gramophone and a maternal uncle and self-taught violin virtuoso played along. An attractive feature of Papa’s day was his whistling and playing of the harmonica, providing the household with a kind of crash course in classical and semi-classical music. The mandó moved him very especially (he ensured that it featured at his children’s wedding parties) and so did two popular Konkani films of his time which, he said, ‘foster Goan patriotic feelings’. The Goan reality, however, was a far cry from what he had envisioned, so I can say with Wodehouse that ‘if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.’

No tribute to our father would be complete without a reference to our dearest mother Judite da Veiga, who was the love of his life, the reason of his being. On his death bed I heard him thank her for half a century of togetherness. She, their five boys and families, was all that he ever wanted. We have lost him in body, not in spirit. He has become greater in death, our strength and consolation, our conviction that there can be no anxiety for the future….

Herald, 19.01.2020, published an abridged version

For this full version see Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), March-April 2020

https://issuu.com/casadegoa/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n3_-_mar-abr_2

A Life in Translation

Quasi-Memoir-1

I was clueless as to 30 September, International Translation Day, instituted two years ago. I got the lowdown from that enterprising, Herald journalist Dolcy D’Cruz: for the purpose of a feature to mark the occasion, she'd sought to know what translation meant to me and how I went about my activity.

‘Translation is a magical thing,’ I said to her, almost instinctively. ‘Not only does it help spread information and speed up business across the globe, it promotes cultural understanding.’

At the back of my mind were Tolstoy and Dostoevksy, Verne and Dumas, Anderson and Grimm, authors whose native languages I didn’t know. And I shed a tear for those who had to depend on renderings of Shakespeare, Dickens and Twain, and why not, Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie and P. G. Wodehouse. I was lucky to read them all in the original, as I was, when it came to my father’s recommendation of a Portuguese staple diet: Júlio Dinis, Garrett, Camilo, Eça, Ramalho, Aquilino, for a novice; and my additions: Pessoa, Torga, Namora, Agustina, Lobo Antunes, and Saramago (with a pinch of salt).

Literary translations have made the world richer. And it’s not literature alone that has depended on translations; even the most disparate subjects like history, medicine and everything in between have benefited from them. If in the early twentieth century, seminarians in our archdiocese had to depend on Latin texts, it wasn’t only because that’s the official language of the Church; there were no translations available in the vernacular!

Even more picturesque was my doctor aunt’s story about the use of French manuals at the Goa medical school, as late as the 1950s: students had soon cultivated the art of reading them aloud in twos or threes, and straight in Portuguese. That was magic!

Early days

As aural memories came gushing, I began to realize that translation had indeed been an organic part of my life. As a child juggling several languages, from Portuguese and Konkani at home, to English, French and Hindi at school, oral translations happened almost as a matter of course. I would reproduce in Portuguese information that I’d received in English, and vice-versa. Mixing of lingos and literal translations were a big no-no, whereas idiomatic language was warmly encouraged.

Yet, translation per se was never the main concern; the accent was on reading good literature and relishing good conversation; it was about having a dictionary at hand and looking up the meaning of an unfamiliar word; it was about finding le mot juste. It was no cakewalk but, looking back, the long walk was so worth it. And a job well accomplished always translated into joy.

After my father’s remark, ‘Languages are an asset; master them while you’re young,’ the next best thing that stuck in my head was Bacon’s famous quote: ‘Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.’ This was like a command from on high. Or for that matter, F. J. Sheed’s dictum that ‘… minds feed on minds, you cannot nourish your mind with a chop,’ struck me as very sensible.

After handling English texts, ‘ex officio’, on school days, I would spend bits of late Sunday mornings decoding Portuguese texts under my father’s tutelage. By the end of high school, I had begun devoting an hour or so to transcribing All India Radio afternoon news bulletins for O Heraldo. And why? Now it just seems so funny: I’d found this arrangement vital since Goa’s first daily, which was on its last legs, no longer subscribed to news agencies and was starving for news. I also thought it would reassure my father who, after retiring prematurely, lent a hand at the paper – for the love of the Portuguese language and practically for free.

In the public domain

That happened to be my first stint with translation outside the domestic sphere. I didn’t think any good would come out of all that. But, three years later (1983), when I least expected it – I was in the first year of college – the then Jesuit priest Teotonio R. de Souza invited me to work as a research assistant at the newly established Xavier Centre of Historical Research of which he was the director. My task was to create summaries in English of the Mhamai Kamat papers written in Portuguese and French. I was also pleasantly surprised that he’d entrusted me two of his research papers for translation. That we argued playfully about his views is quite another matter entirely!

After my MA at the University of Bombay (1985-87) and a language and culture course at the Universidade de Lisboa (1988), I had a short stint as a lecturer in Portuguese at Dhempe College, Panjim, chiefly, to replace my father who was down with malaria. After a few months, I hesitantly took up an interpreter’s job at the Embassy of Brazil, lured by the national capital. On arriving there, however, I was stunned to see that I would be assisting an eighty year old: Pylades Prata Tibery, a Brazilian national of Greek and Italian ancestry, introduced himself as a ‘juiz de gado’ (cattle judge).

Tibery and I crisscrossed the subcontinent, by road and rail, trailing the Nellore buffalo – a breed that, according to the garrulous old man, Brazil had imported from India in the early twentieth century. Our activity was interspersed with a generous exchange of notes on European and Brazilian Portuguese. While the English of his school days was amusing, even more so were his colourful descriptions of ‘convivial society’ expressed in his native Brazilian.

Well, I could hardly be buffaloed by a more outlandish task even if handsomely paid, as indeed I was. It marked the beginning and the end of my honeymoon with translation/interpretation as a full-time job... On my return to Goa, I took up teaching as a career. After the initial hiccups, I found fulfilment in interpreting my students’ thoughts and feelings, and translating their ignorance into knowledge, their anxieties into hope, and their ambitions into reality! Translating and interpreting could now only be side gigs, mostly to oblige friends and family. For instance, I liaised at a couple of wine festivals and carried out humdrum legal translations, among other things. Even these I could no longer endure when I finally had my eyes set on translating literary, historical and spiritual texts. That would surely be a balm to my spirits.

Literary translation

Sometime in 1995, a brief encounter with Editor Arun Sinha of The Navhind Times provided that go. Keen on setting up a literary page to step up his paper’s Sunday magazine, ‘Panorama’, he suggested I work on Goan short stories written in Portuguese. I did produce quite a few translations, but alas, inevitable changes on the home front constrained me to discontinue the series.

But in spite of everything, mine has continued to be a life in translation, of which the Herald article gives a glimpse (see the link below).

(To be continued)

Aquela doce palavra ‘Fátima’…

Era eu ainda menino quando ouvi da boca da Avó Leonor a história de Nossa Senhora de Fátima. Nessa altura, foi o enredo, ou seja, a descrição pastoral, que deveras me impressionou; e também o facto de a Mãe de Jesus ter pedido a recitação diária do Terço e que os maus se tornassem bons para poderem alcançar o Céu.

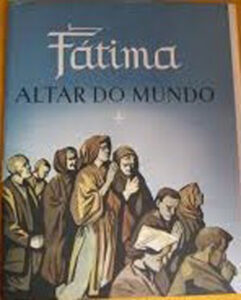

De vez em quan do ia lendo umas publicações sobre Fátima que tínhamos na nossa biblioteca em casa – uma delas, Fátima, Altar do Mundo, de João Ameal. Atraía-me esse fantástico subtítulo – “Altar do Mundo” – bem como as lindas fotografias a preto e branco.

do ia lendo umas publicações sobre Fátima que tínhamos na nossa biblioteca em casa – uma delas, Fátima, Altar do Mundo, de João Ameal. Atraía-me esse fantástico subtítulo – “Altar do Mundo” – bem como as lindas fotografias a preto e branco.

Uma outra publicação que costumava folhear era o Souvenir publicado em Goa por ocasião do cinquentenário das Aparições de Fátima (1967). Tinha artigos da autoria de escritores goeses – inclusive hindus – escritos em português, inglês e concani.

Nesse opúsculo vi pela primeira vez uma foto memorável de que falava meu pai: a Imagem da Virgem Peregrina a atravessar o rio Mandovi, a caminho da Velha Cidade, no dorso dum gasolina que se apresentava em forma dum grande cisne branco fabricado por artistas goeses. E, desembarcando junto ao Arco dos Vice-reis, essa imagem seguiu em magno cortejo até o local onde iriam ser rezadas, simultaneamente, 153 missas, a representar as Ave-Marias do Rosário! Que imponente cena! Nessa visita que se realizou de 29 de Novembro a 12 de Dezembro de 1949 a Imagem percorreu o território de Goa.

Daí a vinte e cinco anos, ou seja, em 1974, foi anunciada uma outra visita da Imagem. Desta vez, houve grande polémica na imprensa local. Não me lembro qual foi o argumento principal; sei só que se tratava de um debate entre duas gerações de clérigos goeses. Porém, quando chegou a Imagem houve grande concorrência dos fiéis. Com os meus 9 anos de idade fiquei com esta dúvida: como é que podia haver duas opiniões sobre a visita da Mãe de Jesus?!

9 anos de idade fiquei com esta dúvida: como é que podia haver duas opiniões sobre a visita da Mãe de Jesus?!

Entretanto, constituíam já uma tradição consagrada as chamadas procissões de velas, que se realizavam na capital, em Maio e Outubro. Era entoado um e outro cântico em português. Embora parecesse um simples ritual herdado a Portugal, para mim era esse país era o “povo escolhido” dos tempos modernos (já que o antigo não se portara bem!)

Também meu pai, de saudosa memória, sem nunca se esquecer do sentido mais amplo da mensagem de Fátima, parecia frisar o lado português do grande acontecimento que se tinha dado em Fátima, exprimia esse sentir no seu poema “Portugal e Fátima”, que veio publicado n’O Alcoa, de Alcobaça:

Portugal e Fátima Primeira Grande Guerra… Só sangueira, Luto e desolação por toda a Terra!… Angustiada, aparece, pois, na Serra A nossa Virgem Mãe numa azinheira (Cova da Iria); e diz com emoção que vão cessar as hostilidades (é a bonança a seguir a tempestades). Anima o mundo à sua reconstrução. E a Portugal diz:- Eis que te darei Dois jovens que guiarão nessa peleja: Um, que traz veste da cor de cereja; E o outro, de quem muito justamente d’rei: Tem muito sal na fala e afasta o azar.– E assim foi, pois: seguira-se uma era De real prosperidade e paz sincera, Por cerca de meio séc’lo, sem armar… Tal como não há rosas sem espinhos, Não podem faltar cravos nem cravinhos Que perturbem a vida nacional Neste sempre querido Portugal! Mas, haja o que houver, disse a Senhora de Fátima que é sua protectora nata:- “Meu Coração, pois, triunfará”. E, quem acreditar não poderá?

Em 1987, tive o ensejo de visitar Portugal. Fui a Fátima, onde vi peregrinos de joelhos; e uns a cantar e outros a chorar… Emocionante! Impressionou-me bem o recinto do Santuário e a vasta praça pública mas fiquei triste por ver uma intensa actividade comercial ao redor!

Entretanto, fui reflectindo sobre o facto de Fátima não ser um mero sítio ou história: os três pastorinhos eram afinal personagens ímpares no palco internacional e arautos da mensagem divina que merecia bem ser escutada pelo Planeta Terra.

Depois que voltei a Goa, em 1988, estive em contacto com a Sociedade Brasileira de Defesa da Tradição, Família e Propriedade, que tinha acabado de publicar o livro intitulado As Aparições e a Mensagem de Fátima nos manuscritos da Irmã Lúcia, de autoria de António Augusto Borelli Machado. Este livro teve depois uma edição inglesa, feita em  Goa. Eram os anos do desmoronamento do Império Soviético e outros acontecimentos apocalípticos cuja explicação completa se encontrava na mensagem de Fátima.

Goa. Eram os anos do desmoronamento do Império Soviético e outros acontecimentos apocalípticos cuja explicação completa se encontrava na mensagem de Fátima.

Tornei-me ainda mais devoto da Senhora de Fátima. Mas enquanto eu fitava a sua dimensão universal, Nossa Senhora olhava, com carinho maternal, para a minha vida pessoal: ajustar-me-ia com a Isabel, nascida em 13 de Maio, e levando por isso os nomes Maria e Fátima!

Cinco anos depois, casámos nesse dia. No fim da missa do casamento a Isabel fez (e eu renovei) a Consagração a Nossa Senhora segundo o método de S. Luís Maria Grignion de Montfort!

Uma e outra pessoa, católica mas também supersticiosa, nos tinha recomendado não casar no dia 13, sexta-feira. Mas pusemo-nos, a Isabel e eu, incondicionalmente a favor dessa data.

Um ano e meio depois sucedeu-nos algo que essas pessoas devem ter tomado como plena justificação dos seus palpites. Nascia-nos um menino – Fernando – que, pouco depois, começou a ter problemas bastantes graves! Pensámos, porém, que Deus podia mandar uma prova dessas a qualquer pessoa; com que direito poderíamos ser uma excepção? O importante era Deus estar connosco, como realmente esteve, e continua a estar!

No hospital, onde passámos os primeiros três meses da vida do Fernando, cheguei a ler, com grande consolação e deleite espiritual, o livro Fatima, de William Thomas Walsh. Foi um dos poucos livros que pude ler durante o período da crise por que passámos, a Isabel e eu, junto com a família inteira.

Tomámos tudo isso como uma prova da nossa fé; e tínhamos já recebido a resposta a todas as dúvidas suscitadas no interim: era a Senhora de Fátima que nos vinha ajudar a encarar de forma sobrenatural a vida, esta nossa peregrinação na terra.

Fernando não se curou completamente mas sucedeu algo que a medicina não achava possível... Está estável, com uma alegria de viver, e é devoto de Nossa Senhora!

Uns anos depois nasceu-nos o Emmanuel, que leva o nome do Esposo de Maria Santíssima: José! E quando nasceu a Vera, uns dias após a morte da Vidente Lúcia, foi ela baptizada também com esse nome de luz.

Eis algumas facetas da nossa relação com a Mãe Celeste… E eis porque ainda nos fala ao coração aquela doce palavra Fátima.

(Em conversa com Cristina Arouca, em 2012)

(Em conversa com Cristina Arouca, em 2012)

Ver:

Fátima no Mundo, de Manuel Arouca e Cristina Arouca Editora Ofício do Livro, 2016) https://www.amazon.com/F%C3%A1tima-Mundo-Portuguese-Manuel-Arouca/dp/9897414320) Fátima e o Mundo, documentário, Ep. 611, Dezembro de 2016: Fátima e a Ásia e a Oceânia. https://www.rtp.pt/play/p2909/e263645/fatima-e-o-mundo

The Two Abbés

Who in Goa hasn’t seen that striking bronze figure of a tall man in a flowing robe, with a lady tumbling down at his feet? Sculpted by Ramachondra Panduronga Kamat and erected next to the Adil Shah Palace, the statue is now in its seventy-fifth year. It was a tardy tribute to a nineteenth-century Goan celebrity – Abade Faria – considered the ‘father of modern hypnotism’.

For every passer-by that admires that lofty monument, there are thousands the world over who would be reminded of a literary character of the same name: Abbé Faria from Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte-Cristo. This adventure novel was published a century before that statue was put up in Panjim.

Are the Abade and the Abbé one and the same person? Faria is a surname; abade and abbé mean ‘abbot’ in Portuguese and French, respectively. The historical Faria only served as a literary inspiration for the celebrated French writer. Some parallels are obvious between the two figures but not all of them do justice to the flesh and blood Faria.

The real Faria was born José Custódio de Faria, in Goa, then Portuguese India. After eight years of priestly studies and a doctorate in Rome, he lived in Lisbon for the same number of years. Finally, he settled down in Paris, where he spent over thirty years, with a year or so in Marseilles and Nimes. In France he was referred to as Abbé Faria.

Dumas’ learned Abbé is a linguist, philosopher, and a strong-willed man. Our Abbé was proficient in philosophy, theology, history, and he intuitively discovered hypnotism; he knew Konkani, Portuguese, Latin and French; and was a resolute man. The physical attributes of the two are similar, except for their height.

The novel is set in the bay of Marseilles, where the fictional Abbé is imprisoned; the real Abbé worked in that port town as a professor of philosophy, in 1811. The former is nicknamed ‘Mad Monk’ by the prison staff; quite intriguingly, our Abbé too was derided by doctors, writers and fellow pastors for his ideas on hypnotism, in Paris (1813-19). Similarly, the Abbé’s description of lodging and boarding in jail could well be a mirror image of the real Faria’s living conditions at the Orties convent. Dumas’ inspector of prisons would be the equivalent of an actor, Potier, who lampooned our Abbé in Jules Verne’s fateful play, Magnétismomanie.

Coming now to Abbé Faria’s tunnelling for three long years: it could be interpreted as the real Abbé’s quest for ideas and materials in support of his theory of sommeil lucide (lucid sleep). When they died of fulminating apoplexy, in their sixties, both characters had their books still unpublished. The real Faria’s book De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man) came out posthumously; the remaining three volumes were untraceable, much like the jailed Abbé’s book that was never found.

While Dumas’ Abbé is an Italian, born in Rome; the Goan Abbé was born in the ‘Rome of the East’. The hero, Dantès, once journeyed to India, whereas José travelled from India to Europe, and never went back to his homeland. Interestingly, the fathers of both have important roles in their sons’ lives. Could Dumas have known that José’s father in Lisbon was under house arrest for his nativist ideas, and that many of the conspirators of 1787 in Goa met with a fate worse than death? Apparently, José’s father and Dumas himself were both republicans at heart.

Finally, the treasure that the Abbé highlights in the novel could be a pointer to the treasure that the historical Abbé Faria endowed us with, in the form of hypnotism: this has long been an invaluable aid to the physical and mental well being of humankind.

It is sad that Faria fans find it hard to separate fact from fiction: shrouded as he is in deep mystery, the real Faria comes out largely disfigured. But given that historians and medicos took no steps to fix that shortcoming, how can one fault Dumas for taking artistic licence? After all, the man who died, disdained and forgotten, on 20 September 1819, was kept alive in the pages of The Count of Monte-Cristo. It now behoves us to put the historical Faria on a pedestal much higher than the one on which he is placed in Panjim’s main square.

Celebrating Braz and Jazz

"Raga Rock" was a much-deserved tribute to Goa-born Braz Gonsalves. Thanks to this presentation by Panjim-based Communicare Trust run by Nalini Elvino de Sousa, Goa got to sing paeans to a Jazzman who keeps a low profile after decades of showmanship in the Indian metros.

At the Kala Academy, on 14 June, I was charmed by the sight of a senior citizen at the entrance, welcoming guests with a gracious smile. Many passed him by, unsuspecting that he was Braz Gonsalves himself. For sure, many jazz aficionados have heard of the man and enjoyed his music; very few would have met him in person.

A few minutes later, the very same man wearing his trademark flat cap stole the show. At 86 years of age, he regaled a packed auditorium with his magical, golden saxophone. He was joined by his good ol’ boys: Louiz Banks (who formed the great Indo-Jazz Ensemble, with Braz); Karl Peters, India’s foremost bass guitarist, and drummer Lester Godinho, not forgetting his own, musically talented wife Yvonne ‘Chic Chocolate’ Vaz, daughter Sharon, son-in-law Darryl Rodrigues, and the youngest – and perhaps the most talented of them all – his grandson Jarryd Rodrigues. “Grandfather meets grandson,” boomed Banks, who also remarked that “the legacy of Braz Gonsalves is in the safe hands of his grandson Jarryd.” They made an amazing duo.

What a spectacular evening of jazz! And the music will play on, if the revelations on stage are anything to go by: Jazz pianist Jason Quadros, Portuguese-born soprano Maria Meireles, Anthony Fernandes (bass) and the ‘cool’ Coffee Cats comprising Ian de Noronha (keyboards, bass and melodica), Neil Fernandes (guitar and vocals), Jeshurun D’Cruz (drums), Jarryd Rodrigues (alto and soprano saxophone), Gretchen Barreto (vocals), Ajoy D’Silva (trumpet), and Lester D’Souza (tenor sax).

The music segment (vocals and instrumentals) was preceded by a musical skit in which sixteen children recreated the story of Braz Gonsalves’ life which began in Neurá-o-Grande, a village my ancestors hail from. And that was an added reason for me to celebrate Braz and Jazz!

Good Friday Procession in Panjim

The 3 o’clock, Good Friday service at the city church of the Immaculate Conception comprises a poignant Crucifixion tableau.

Soon thereafter, a procession of Senhor Morto (Dead Lord) on an andor (black canopied wooden platform carrying a life-size statue of Our Lord who died on the Cross) starts off, with a statue of Our Lady in trail. It wends its way through the main thoroughfares (the church square, a section of 18th June, Pissurlencar, past Azad Maidan), making a major halt to pray at the chapel formerly attached to the mansion of a Portuguese noble family. The cavalcade then proceeds via M. G. Road and Dr D. R. de Sousa, past the Garcia de Orta Garden, and up the church stairway.

The pious march takes approximately 90 minutes. It is animated by five decades of the Marian rosary recited over speakers fitted at several points; and by Lenten hymns sung by a choir to the accompaniment of a brass band. The circuit is marked by over ten descansos (halts). At these points, penitents, all of them de rigueur, in funereal attire, flock to the two statues. Members of other religious faiths also pay their respects; many watch in awe or stand at attention (I noticed a policeman saluting).

One such halt is at a quaint chapel traditionally called 'Capela de Dom Lourenço', located behind what is now the iconic Hotel Mandovi. In times past, the chapel was part of the manor belonging to Dom Lourenço de Noronha, a Portuguese nobleman, who had acquired a large estate in the then incipient city centre. After the palatial mansion was razed, the chapel was handed over to the care and possession of the city church. Alas, the venerable structure is in a state of disrepair.

On the said route, two Hindu families (Caculó and Neurencar) traditionally offer garlands. Businesses brighten up their establishments, or simply light candles and burn incense on the adjoining pavements.

In a coda to the baroque event is a sermon (Sermão da Soledade de Maria) at a stair landing: here, from a balcony that serves as a makeshift pulpit, a priest extols the virtues of Mary and highlights her present solitude. The congregation listens in silence even while vehicle noises spoil the ambience.

The statues return to the church for final veneration. By 8 o’clock, they call it a night!