St Patrick in Goa?

What’s this fanfare about St Patrick’s Day in Goa, which, if reports are to be believed, is slowly gaining popularity in the state?

St Patrick is a saint of the Catholic Church. The patron saint of Ireland, he is credited with having driven away serpents from the island country, though others say the reptiles never existed in the first place! Understandably, it is a religious feast that has entered the Irish lore, but since when in Goa? If it were a local religious feast, at least one church or chapel here would have celebrated the day…. Not that I know of.

So it appears that this is a new festival being foisted upon the people of Goa. With due respect for the enthusiasm of the Irish settled in our midst – whatever their number – one thing is sure: St Patrick’s Day is not a celebration that has sprouted from the local soil. And in its present avatar, it is less of culture and more of show biz….

Alas, much like Carnival, it is being portrayed as a Catholic festival. But the truth is that this celebration is not connected to religion or culture. It is simply about partying; it is about merry-making and having a good time. And to give it a good name, there is usually some fund-raising attached to it. This may slip away with the passage of time, but the amusements will surely stay.

It is never a good idea to cash in on or commercialize religious dates or events. Look what they’ve done to St Nicholas. People don’t even recognize his name unless pronounced ‘Santa Claus’! The Saint has been made use of to ruin the tender spirit of Christmas the world over. Are we going to use St Patrick’s revered name to destroy the solemnity of Lent in Goa?

It may be true that the Lenten restrictions on eating meat and drinking alcohol are lifted for the sake of this day in Ireland. But in Goa? It is as though the proverbial serpents have sneaked in here!

Let me say with due apologies to the Bard of Avon: If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no Goan ever celebrated. At any rate, pat must come our prayer to St Patrick: “Mag amche pasot!” Pray for us.

(First published in Herald, Panjim, 18 March 2017)

Lent, an irresistible balm for the soul

Haven’t we felt listless, not to say ill at ease, about Lent, sometime in our life? As a child, I tagged along with my parents to liturgical services that made little sense. Not surprisingly, on reaching the age of reason, I had to be cajoled into attending them. Then, suddenly, I got a break. I found motets, songs for the season, composed by Goa’s unnamed musicians of old, to be an absolute feast for the ears, alongside similar compositions by Bach, Palestrina and Mozart. I also discovered, quite ironically, that the Via Dolorosa in the balmy evening breeze and to the chirping of birds in the woods of Altinho was not so dolorous after all!

Much as I delighted in those two little secrets, at one point I felt an interior dryness, a sense of futility, as though I were trudging a wasteland. The saving grace came from my grandmother’s exemplary life, which was far better than precept. Likewise, my parents’ quiet commitment to the Faith, amidst their daily toil and moil, provided important insights into the valley of tears we live in. And Scripture wrapped it up so beautifully: “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?” (Mt. 6: 26)

Clearly, the rituals that I had cheekily dismissed yesterday changed into victuals for the spirit today. And as another season of Lent comes round, I know just how it will turn out, how they will sustain me…. Beginning Ash Wednesday, I will go to church more often than usual, for Mass and Stations of the Cross. On a hopefully bright and festive Palm Sunday morning, I will feel cheery. Yet, by evening, my mood will change hugely – as it always did when I witnessed the spectacle of the full-size statue of the Suffering Lord emerge from the immaculately white church of the zigzag stairway, to join the faithful clad in dark shades, in a penitential procession through the streets of the capital.

What a poignant start to the Holy Week! It’s the last lap of an all-embracing spiritual journey. You’ll probably catch me shaking off distractions on holy Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. Through the rest of the week, I will be all eyes and ears to the Mystery of mysteries replayed in the Paschal Triduum, from the moment of that bittersweet Last Supper on Maundy Thursday through excruciating Good Friday and triumphant Easter Sunday. Soon, the week’s darkness will give way to light and its drabness will translate into loud proclamations. The faithful will be beside themselves, singing in an unending refrain: “No one can give to me that peace that my Risen Lord, my Risen King can give.”

It pays to be fools for Christ; Chesterton’s “Donkey” is proof that there will be no regrets. The thought of self-privation, which had bugged me when young, doesn’t assail me. I find it easier now to give up a favourite food or a much-loved pastime. Penance and sacrifice, besides fostering self-discipline and tempering our desires, are game-changers. They help to boost one’s spiritual life and improve our physical health. We are led to find ways and means to step up our knowledge of our faith; perform acts of kindness and mercy, wherever we may be; pray for others, and clean ourselves inside out by means of a holy confession. Before long, we learn to slow down, while the rest of the world is in a rat race, enjoying in a fool’s paradise.

It is reassuring to think of Lent as pilgrimage toward the profound mystery of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Benedict XVI says it is also “a privileged time of interior pilgrimage toward Him who is the fount of mercy. It is a pilgrimage in which He himself accompanies us through the desert of our poverty, sustaining us on our way toward the intense joy of Easter.” How, then, can we be listless or ill at ease at Lent when an irresistible balm for our soul is at hand?

(First published in The Times of India, Panjim, 1 March 2017)

Naval Band enthrals

What we know of the Indian Navy is that it safeguards the nation’s maritime borders, enhances international relations through joint exercises, port visits and humanitarian missions, including disaster relief.

What we know very little about, however, is that the Navy prides itself on its band. They perform at events of national and international significance. Those include the Republic Day Parade and the celebrations that culminate in the Beating Retreat ceremony in New Delhi.

Interestingly, the Band, formed way back in 1945, accompanies naval ships on goodwill visits to foreign shores. It has woodwind, brass and percussion sections. String instruments include the violin and the double bass; and among the Indian instruments are the tabla and the dholak. The Indian Navy musician officers, playing in ensemble with the bands of foreign nations, double as unofficial musical ambassadors of the country.

The sixty-six men Indian Naval Symphonic Band is in concert in our State, performing under the baton of the Director of Music (Navy), Commander Vijay D’Cruz, who is of Goan origin. He is assisted by T. Vijayraj. Their repertoire includes fanfare, waltz, folk, swing, fusion, hymns and patriotic music; of which my favourites were 'Le Mariage de Figaro', 'Skater's Waltz' and 'Abide with Me'.

Commander's D'Cruz's composition, ‘Folk Tunes of Western India’, which took the audience on a journey through the states of Western India including Goa enthralled the audience. ‘American Patrol’, a popular marching tune composed by Frank White in 1885, and ‘Shanmughapriya’, a ragam in Carnatic music, followed.

Today’s show at Dinanath Mangueshkar auditorium of Kala Academy was packed to the rafters. It was beautifully compered by Genevieve da Cunha, wife of commanding officer of INS Mandovi, Captain Sanjay da Cunha, whose family hails from Curtorim.

A beautiful mix of great social propriety and bonhomie marked the event. It was a treat to see the officers and their families interacting among themselves and with their guests.

A Ray of Hope from a faith formation seminar

My mind races back to 1977-78, when my siblings, friends and I attended a prayer meeting spread over three evenings, at the Azad Maidan, Panjim. We went with some trepidation since it was a Protestant pastor giving his testimony. What finally clinched it for us was that stirring question “What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world but loses his soul?” which we saw splashed in bold, white lettering across a dark blue banner. Hadn’t a young and impetuous man once been transfixed by those very words? So, reassured by the familiar image of Goenchó Saib, we skipped our playtime and went.

The huge backdrop spanning several columns of the then Albuquerque memorial must have been designed to rope in naive Catholics; its text was ‘gripping’, because we teenagers were groping. In the end the meet did not satisfy us. Notwithstanding the histrionics that mark Protestant gatherings, we did not find the living bread and water that we were seeking; we only found ourselves gazing at Christian teaching through cracked crystal – which is what Protestantism is.

But the good side of it is that it whetted our appetite for manna that only the Catholic Church can give. We realized it was the same old story of not being grateful for what we have until we have lost it – which is the larger point that Stephen K. Ray, popularly known as Steve Ray, drove home at a faith formation seminar titled ‘It’s Great to be a Catholic!’ The event, organized by our Archdiocese at Pilar College Grounds, on 22-23 January 2011, was attended by some two thousand laypeople from across Goa. Given below are highlights of the issues covered by Ray: some treasured doctrines of the Catholic Church; and why dedicated apologists are the need of the hour.

Catholic Treasure

Can we afford to just stand and stare, or be ‘Sunday Catholics’ at best, when there is so much about the Catholic Church to learn and share?

Ray, a former Baptist, began with a moving testimony on how he ‘came into the Catholic Church backwards’. He was attracted by the solidity of the Catholic teaching vis-à-vis the inanity of worship, the skewed interpretation of the Bible, and the relativity of moral teachings, rampant in the Baptist church. Finding it ironical that Catholics, who are privy to doctrinal treasures, “don’t share their faith”, he urged the laity not to regard the faith as something private but rather to proclaim it proudly, for “we are duty-bound to be good evangelists.” He pointed to the USA, where the Catholic Church is growing from strength to strength, in number and quality.

Passing on to ‘Scripture, Tradition and the Magisterium’, all of which the anti-Catholics love to hate, Ray quoted Pope Paul VI, who endorsed the “fifth Gospel” – Israel – which we have to believe in so as to understand Catholic teaching in its entirety. We cannot afford to “throw out the Old Testament, like old bread” because therein lies the foundation of our faith, and of which the New Testament is the fulfilment. Quickly reminding critics who bank solely on the Bible and decry history that the Bible itself is a product of history, the Apologist galloped his way to Caesarea, Phillipi, to uncover the eloquent backdrop to Jesus’ idea of Peter as the ‘Rock’. “If the Catholic flock understood this, none would ever leave the Church,” he said, adding half in jest, “Sheep are stupid, and leave; only the smart ones remain!”

Ray dealt at length with the ‘Papacy: Apostolic Succession and Infallibility’, which is the subject of his book Upon the Rock (Ignatius Press, 1999). He demanded to know why the Papacy is thought by a few to have ended with Peter, when a presidency does not end with the death of a President! He stated that the Pope is ‘the Holy Father’, not because he is sinless but because he is ‘consecrated, set apart for a holy purpose.’ He remarked that, curiously, the Pope is a source of unity for all Christians: for those who believe in him as well as for those who gun for him in unison!

Significantly, the theme inscribed on the backdrop was “You are Peter and upon this Rock I will build my Church, and the gates of Hell will not prevail against it.” (Mt 16: 18) Ray confessed that, as a Baptist preacher, he would pick Catholics like a ripe apple with his standard objection, ‘But where do you find the word Pope in the Bible?’ Now, as a convinced Catholic he counters that with ‘But where in the Bible is it said that you must find everything in the Bible?’ This quip soon turned into a cheery refrain, echoing under the massive blue-and-white pandal: it now serves as an opening rebuttal for budding apologists to consider.

‘Mary’ was another keystone of the Catholic Church that Ray focussed on. To decipher this “great problem for the Protestants”, Ray transported us from the earthly Jerusalem to the New and Eternal City. From the cave (now St Anne’s Church) where Mary was “immaculately conceived” and endured a “tough Jewish life”, we were guided through the awe-inspiring Annunciation and Visitation (7 days’ walk in the Jordan valley, 160 km in 45º C) to the Nativity and the Holy Family’s vicissitudes in Nazareth (to be seen as “God endorsing the dignity of labour”).

Reflecting on the glories of Mary, Ray considered her life post Joseph’s death when Jesus was but 12 years old. It was she who set in motion her Son’s ministry, at Cana, and this established her centrality in God’s plan of salvation. At the time of Jesus’ death “God rewound history”: Eden became Gethsemani and Satan returned as Judas; and whereas at Eden death stuck into the Tree of Life, at Calvary life sprung up at the Tree of Death! And in all of this Mary’s role was unmistakable: her Son became the New Adam and she the new Eve; she revealed herself as the Ark of the New Covenant; was present at the birth of the Church in the Upper Room; and having been assumed into Heaven and crowned Queen (reminiscent of Solomon who enthroned his mother), she remains our supreme intercessor.

Speaking on ‘Eucharist: Source and Summit of Catholic Life’, Ray stated that its definition had remained unchanged for 1500 years until “a bunch of Protestants who called themselves magisterial reformers” began to find fault with it – and then couldn’t come to an agreement on it themselves! This led to hundreds of definitions of “This is My Body… and Blood”. He stressed the need to go back to the typology found in the Old Testament, since it prepares us for the Eucharist, from Melchizedek to Malachi. In the New Testament, Bethlehem (meaning ‘House of Bread’, and where Mary “delivered the Bread of Life”) and the Passover Meal are significant.

Ray pinpointed John 6: 63 as a thorn in the side of the Protestants. He reiterated that the Eucharist is more than just a meal – it’s a sacrifice; and the table of the Lord is more than an ordinary table for that meal – it’s the altar for that sacrifice. Jesus meant it precisely that way – truly, not symbolically – but the Jews were unable to stomach it, and so rejected the Son of God.

Finally, Ray did not mince words on the thorny issue of ‘Salvation’. The first sentence of § 1257 of the Catechism says that “The Lord himself affirms that Baptism is necessary for salvation,” and then the last one: “God has bound salvation to the sacrament of Baptism, but he himself is not bound by his sacraments.” He categorically stated that we gain salvation not through the merit of our good works, or by faith “alone” (as Luther insisted), but by God’s grace and mercy. He picturesquely termed Purgatory as the “front porch of Heaven”. Urging the faithful to believe in Jesus, he noted that the opposite of “to believe” is “to disobey” (Jn. 3: 36).

Historic Milestone

Ray spoke with knowledge and verve, wit and humour. Two question hours were part of the agenda, which saw Ray fielding a wide variety of issues – from the meaning of ‘apologist’ to indulgences; the New Age movements; modest attire; home schooling; ‘property gospel’; contraception; celibacy; tithes; healing services; alternative medicine; and Heaven and Hell. When unaware of a regional peculiarity (viz. the existence of a sect named ‘Believers’ in India) he was eager to learn. He was sharp and answered questions with precision; only once did he fail to disentangle a long list (ecumenism, inter-religious dialogue, etc.), inadvertently, for sure.

Ray is admirable, his style simple and direct, his speech accessible. Above all, he has the force of conviction stemming from an intimate experience of a living God and years of learning and practice – of which have the power to revive a sluggish faith. His approach is “pastoral – not combative or harsh”, as he says of his own book, Crossing the Tiber (Ignatius Press, 1997), a world bestseller, which recounts his momentous decision to turn Catholic.

The Apologist touched our hearts. Braving the heat of the noonday sun, the audience listened with rapt attention, all seated in a shamiana that felt like a makeshift church (but definitely way above any that our ancestors must have witnessed in their primitive, improvised structures). On one occasion, in a post-lunch session, some of us were at the end of our tether, even while the speaker was adjusting the collar mike to begin his talk; and, quite unexpectedly, there came a cool and refreshing breeze – like the Holy Spirit making his presence felt! – and blew away all our troubles.

While, on the one hand, Fr Manuel Gomes’ able interpretation of the talks into Konkani was reminiscent of a similar task that Fr Joseph Vaz undertook for two famous preachers from Portugal at the retreats they conducted in the Goan countryside; on the other, the entire rustic setting of our seminar made us wonder how it must have felt to be listening to pearls of Christian doctrine as they first cascaded from the lips of Our Lord, be it on the mount, by the sea or in the Jewish town.

There is no doubt that Goa was ripe for Ray. We gratefully acknowledge our Archbishop Filipe Neri Ferrão’s personal endorsement of his visit. Not only was this symbolic of a ‘refresher course’ in Catholicism five centuries after the Portuguese missionaries planted the seed; but, more importantly, it was a fitting response, although long overdue, to the historical and contemporary dangers that, from within and without, assail the former bastion of Catholicism in the East. This was perhaps an unprecedented event, and most certainly a historic milestone in the life of our venerable Archdiocese.

In a brief tête-à-tête, our enthusiastic and friendly Archbishop – who, I must highlight, sat through both days – described the faith formation seminar as “refreshing”. He appreciated Ray’s “way of presenting” matters and found it “great to listen to a layman preach”. He had particular regard for him for being “very loyal to the Church.”

For his part, Ray appealed to laypeople and priests alike not to shred the Body of the Church, and endorsed the wisdom of staying under the authority of the Bishop.

The Road Ahead

Here was Apologetics in action, perhaps in a long time! A vivacious Goan apologist, Francisco Correia Afonso, once said something to this effect: We need no apologetic Christians but Christian apologists!

In fact, the Goan priest and lay apologists first emerged a century ago, in the wake of the anti-Catholic and anti-clerical republican regime; they exerted themselves in the service of the Church for five decades, after which there was a lull, because the time had come – as another great convert-apologist G. K. Chesterton put it, albeit with reference to another time and place – “when the Christian [was] expected to praise every creed except his own.”

At Pilar both the Apologist and the Archbishop felt it necessary to pray for a new batch of Defenders to emerge. While Apologetics might seem only a matter of learning to explain and defend our Faith, it is as much a matter of confidence, prayer and commitment. This cannot be a solo venture; the faithful must fervently desire it all together. So can we get our act together? And how do we create the right conditions?

Especially for an apologist, learning should not only mean acquiring general knowledge, but more importantly, acquiring a Catholic perspective on that body of knowledge. For the specialized knowledge required, The Essential Catholic Survival Guide (Catholic Answers, San Diego, 2005) suggests a roadmap beginning with the Bible, and going on to the Catechism, which will help interpret the material of the Bible in the context of what the Church has historically understood it to mean. Then would come a study of the objections made against our faith by anti-Catholic literature and the responses to them. Finally, to successfully rebut both non-Catholics and anti-Catholics one would have to master the arguments put forth by Catholic writers.

But what kind of people would accept the challenge of making time for religious studies and putting them on par with their secular studies? Only they may care to do so who have a profound confidence in God and exercise this virtue amidst the prosaic realities of life. Those of us imbued with materialism, who trust ourselves better than we do God and have no qualms about taking short cuts to ‘success’, oblivious of principles and unmindful of consequences – we are called to do a rethink.

If our preachers and catechists became more spirited, more apostolic, and less bureaucratic, for many confidence in God would not remain just a theoretical proposition; if our small Christian communities interpreted the Bible not as ‘free thinking Catholics’ but strictly as taught by the Mother Church, sects would not flourish; if adult catechesis were taken up with a sense of urgency, our households would become nurseries of apologists; if our faith were nourished beyond Confirmation or the ‘booster dose’ received at Marriage – and if the Sacraments were used optimally – we would never run the risk of having a faithful devoid of faith or confidence in God!

Our learning and confidence can be sustained only by a life of prayer. Whereas we can do nothing on our own, with God there is nothing we can’t do. This requires of us to pray and to undertake all our endeavours prayerfully.

But what does one pray for – why and how? Oh, the fond memories I have of that school catechism that taught us, “God has made us to know Him, love Him and serve Him above all things”! In those days it had perplexed us – ‘But what of my little toys, which I love so much?’ Today that incipient catechism does makes all the sense. If we treasure our moments of interior recollection and cherish the moments of divine inspiration, the joy of Christian learning, confidence and prayer will be effortlessly reflected in our social interaction, to the benefit of all.

A special Apostolate of Prayer, if officially instituted, would help to impress upon our minds the need to pray. The faithful could also be invited to introspect, and to examine issues of the spiritual and material order that they find disquieting and barriers for sanctification. To supplement the questions dropped in the Box at the seminar venue, fresh queries could be solicited from our parish councils, all of which might provide an insight into the mind of our lay faithful.

In due course, learning, confidence and prayer will build character and commitment in our faithful. Then, from them will rise apologists with an unselfish zeal and a spirit of sacrifice, whose habitual posture will not defensive but pro-active they will learn to face public opinion with courage, serenity and self-control; and deal with the adversary with meekness and firmness, capitalizing on the Apostolate of the Presence.

Given that the ways of the world are inimical to the Church, and the secular Press traditionally confuses issues, our Archdiocese could consider setting up a newspaper in Konkani and English to enlighten the people with proper perspectives.

In our day and age it is important to employ all means of communication at our command. This is imperative in faith matters. Hasn’t a lot of water gone down the Mandovi since those sporadic Protestant prayer meetings of the late 1970s? What in yesteryear and to our tender minds seemed innocuous did eventually cause religious indifferentism to grow amidst us. But, thankfully, most of us still believe that it’s great to be a Catholic. And we have no doubt that when the hour strikes the Goan Apologist will be found. We have seen Ray… and we see a ray of hope on the horizon!

(Renovação, Vol. XL, No. 4, 16-28 Feb 2011, as 'Ray of Hope: Reflecting on a Faith Formation Seminar)

Dona Teresinha, as I knew her

Something from within impels me to speak. I somehow cannot contain this gush of childhood memories of the time, way back in the 1970s, when I used to see Dona Teresinha criss-crossing the city in her Datsun Bluebird. I can still hear her voice in the Renascença programme of All India Radio, Panjim. An exponent of Indo-Portuguese culture that she was, right from her Lyceum days, I can picture her in the play ‘Barco Sem Pescador’. Many will remember that, at times, she singly animated the Mass at St Sebastian’s, the Fontaínhas chapel that was so dear to her heart. Her steadfast circle of friends will recall that she and her family never let go an evening of entertainment that included song and dance, particularly the fado and the mandó, which she sang and danced with verve. A lady of many parts, she was confident, smart, creative and forward-looking… ahead of her times in more ways than one.

Let me now fast forward a little, beginning some eight years ago, when I had the fortune of knowing Dona Teresinha a little more closely. That’s when I gathered that she wasn’t the stern person that she seemed when her car whizzed past us children. She had happily sacrificed her career as a pharmacist to become the dedicated wife that she was to Dr Hugo and devoted mother to Carlos and Jorge, a friendly mother-in-law to Marlene and Silvia, and doting grandmother to their four bouncy kids. She was a meticulous housewife, a good cook and gourmet. An excellent hostess, comfortable with people of all ages and stations, she was a great talker and a good listener. Thanks to her vivacity, there was never a dull moment in her company. Her joie de vivre, emblematic of Panjim’s Latin Quarter that she graced, was truly infectious: This stood her in good stead when, in her last years, she was in indifferent health – indeed in a state that would have some lesser mortal slide down the slippery slope of self-pity.

Early on 15th instant, after a pall of gloom had descended upon our household on hearing that Dona Teresinha was no more, I chanced upon an inspirational little story in the Herald, which I wish to share with you for its significance. It is the story of a lady in her twilight years. As she moved into a nursing home, she was seen to be very happy about the room allotted to her. ‘But you haven’t seen the room yet,’ said the health care staff. In fact, she never really would, because she was blind; yet, in her good poise, she replied, ‘That doesn’t have anything to do with it. Happiness is something you decide on ahead of time. Whether I like my room or not doesn’t depend on how the furniture is arranged… it’s how I arrange my mind.’

The brave lady further said – and it could well have been Dona Teresinha exclaiming this – ‘I have already decided to love my room… it’s a decision I make every morning when I wake up. I have a choice: I can spend the day in bed recounting the difficulty I have with the parts of my body that no longer work, or get out of bed and be thankful for the ones that do. Each day is a gift, and as long as my eyes open, I’ll focus on the new day and all the happy moments I’ve stored away… just for this time in my life.’

That reads like Dona Teresinha’s credo! And this is just the time to call to mind her edifying fortitude! She lived life to the fullest, enjoying the good things that it has to offer. Not one to be cowed down, she displayed an energy and optimism rare in our day and age; and despite her troubles, she went out of her way to comfort the other. I must say that one such other was our son Fernando – a ‘special child’, to whom Dona Teresinha doled out special attention. At any social gathering she made it a point to spend moments with him, to see him laugh and sing. He loved it, and he loved her for that.

It is this ability to reach out that will remain in my mind as the single most potent image of this amazing lady. No doubt, Fernando will miss her…. We will all miss her. But in her case we can say with the Poet, that ‘Death shall be no more. Death, thou shalt die’ – which means that Dona Teresinha will live forever!

(Herald, 25 April 2010)

State Control of Church Property: Unwarranted, Perilous and Counter-Productive

The proposal for State control of Church property has been under discussion, for the last month or so, alas, without any well-defined parameters. The saving grace is that this is a ‘private member’s bill’, so to say, thrown into the public space, and not a State-sponsored debate. Nonetheless, it would be worthwhile to examine some of the disquieting aspects of the subject per se, with particular reference to the proceedings of the seminar on the topic “Should there be a law to protect the properties of the Church?” which was held at the Goa International Centre on 28th July 2009.

Why now? – Precisely what has prompted this debate on State control of Church property in Goa is a mystery. At the said seminar, broad remarks and vague allegations were made about the functioning of the Church; there were some sweeping generalizations, too, mainly because the speakers failed to distinguish between the situation of the Church in Goa and the rest of India. As a result, none of them were able to convincingly state what is wrong with the status quo. If at all the present law regulating relations between the Church in Goa and the State is violative of the law of the land, as it was made out to be, how has the law been in operation for almost five decades? The fact of the matter is that the impugned law is not violative, because Ordinance No. 2 of 1962, promulgated by the President of India, provided for the continuance of that law and many others.

The theme of the seminar was artfully worded. It gave one the impression that the Church had solicited help and so the State was going to privilege her with a law protecting her properties from whosoever. While this was only too good to be true, it was also unnecessary, because the Church today is not seeking privileges any more than she rightfully has; what she eagerly desires, however, is conditions conducive to working peacefully within a secular framework.

Is ‘Secularism’ pliable? – Secularism would ideally mean total separation of Religion and the State, leaving no room for the latter’s intervention in the affairs of religious bodies. In a free society the State has to refrain from interfering with matters of a religious nature; its duty is to ensure that individuals can freely profess, practise and propagate their religion. In India, these rights can theoretically be abridged on grounds of public order, morality or health; the State can even make a law regulating or restricting any economic, financial, political or other secular activity associated with religious practice. But all this has to stand the test of “reasonable restrictions”, and it is incumbent upon the State to prove the need for change, lest the idea of secularism should turn pliable to the State’s whims and fancies.

Perils of State Intervention – One may tend to believe that State intervention is ‘safe’, considering that the rights of the minorities and the freedom of religion stand guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. One may not even feel threatened by some initial State involvement strictly limited to the secular part of a religious matter (say, the scale of expenses to be incurred by a religious institution in connection with rites and observances). In practice, however, such intervention can be an irritant or worse, an intrusion in the religious affairs of a body. Hence it must be ensured that the State intervenes only in extremis.

At any rate, is the Church in Goa a fit case for State intervention? And whatever the modalities of control sought to be exercised on the Church in Goa, citizens would, in the first place, doubt the State’s credentials for such a task! This is not to question the sovereignty of the State but only to emphasize that the State has almost always been a poor manager. For instance, by its intervention, a centuries-old, home-grown and much loved institution like the Ganvkari or Comunidades is in a shambles today. Such is the track record of the State that one can foresee that its control on Church property could result in gross mismanagement, appropriation of funds, encroachments, sale and alienation of lands, and the dismantling of the Church infrastructure, leading to a gradual demolition of the religion.

Political and administrative interference from the State is something that Boards and Trusts of some religious communities outside Goa have often complained about. Some faith communities were compelled by the civil law to have State-managed bodies appointed to run their affairs, because of certain circumstances related to the pre- and post-Independence history of their respective faiths. For them, State intervention became a necessary evil, whereas in Goa history took a different course. Therefore the argument that all religions, everywhere in India, must be on the same footing – or, in other words, suffer from the same malaise – is simply not tenable!

State within a State? – It was pointed out with gusto at the seminar that there cannot be a State within a State. Fair enough. But why cast a slur on the Church in Goa? Has the Church thrown a challenge or posed a threat to the secular State?

The ‘State within the State’ syndrome is perhaps true of some of our business houses. How else does one explain the lingering case of the decrepit River Princess? The concerned business house rules the waves, suggesting that they never will be slaves (with due apologies to ‘Rule Britannia!’). Indeed, they are a State within the State!

Or is it simply the magnitude of the Church’s holdings that makes her look like a State within a State? If yes, let this yardstick apply to our mineral ore exporters; they have to be held accountable for creating environmental problems – and what is more – while making profits on what is essentially State property! Will there ever be the political will to intervene in the internal affairs of these erring business houses?

In contrast, Church assets, mainly comprising donations and gifts from members of the community, have several onuses to be fulfilled. They are held by specific Trusts and their proceeds employed for charitable purposes, particularly education and health among the poorest sections and across faith communities.

Finally, is it the influence that the Church wields in public life that makes her look like a State within a State? Then the same objection should logically extend to the whole of the Fourth Estate!

And at this rate, we shall soon cease to be a democratic State!

Has the Church been above the law? – The world over, the internal affairs of the Catholic Church are governed by the Canon Law. Thanks to her international juridical personality, the said law is admissible in the court of law, since it is not at variance with the civil law. Hence the question “Can you allow any religious head to exercise his power without any regulation?” is malicious, and offensive to the head of the Church in Goa. While observing that “any activity ungoverned by law is lawlessness and would lead to arbitrariness” the speaker failed to recognize that India suffers miserably from lawlessness and arbitrariness despite a proliferation of civil and criminal laws (or sometimes because of it)!

So was it right to peremptorily accuse the Church of ‘lawlessness’? As an institution she enjoys a centuries-old tradition of respecting the canon, civil and criminal laws, and this has naturally made her members law-abiding citizens of the country and the world.

Unique Goan Situation – A look at the situation in Goa as a former Portuguese colony should provide answers to many a nagging question. It is well known that in 1961, in support of the many solemn promises that had been made earlier with regard to preserving Goa’s identity, many Portuguese laws were accepted by the Republic of India – for instance, the Portuguese Civil Code, now hailed by all communities in Goa as being fair and progressive and by the Union of India as a model for the country.

Now this has privileged the Hindu, Catholic and Muslim communities in Goa vis-à-vis their pan-Indian counterparts. And it is within this historical framework that their institutions have been functioning, be it the Confrarias, Fábricas and Cofres of the Catholics or the Mazanias of the Hindus. Now, should all these institutions that are unique to Goa change only because they do not conform to a pan-Indian model? If so, where is the principle of Unity in Diversity?

Therefore, the contention that the existing law in Goa regulating the relations between the Church and the State should be modified for the same reasons and to the same extent as it was modified in Portugal, as authoritatively stated at the said seminar, is unacceptable. Are we still tied to the apron strings of Portugal (the proverbial ‘colonial hang-over’) or conveniently blind to the fact that the Goan/Indian Christian situation is different from the Portuguese?

Transparency and Accountability – This is of the essence. The Catholic Church in Goa is equipped from within to ensure the same in temporal matters, the General Statutes of Confraternities and Rules and Regulations of Fábricas & Cofres being two main examples. There is an ever-increasing participation of both the clergy and the laity in all her institutions, which amounts to an internal system of checks and balances. There is a well-established hierarchy to oversee the same. Besides, the Church is subject to all the laws of the land, including the agrarian reform; her accounts are audited, like those of any other civil body, and she pays taxes to the State without any special exemptions. This time-tested organization has found acceptance the world over; so why all this nitpicking here?

Therefore, to allege (on behalf of the State) that the assets of the Church are being mishandled is a classic example of the pot calling the kettle black! Can the State legitimately claim that it utilizes public assets in a responsible manner? Isn’t mismanagement or embezzlement of funds the order of the day in the State? If stray occurrences of this nature inside the Church can justify State intervention, then the reports of chaotic happenings in the country surely call for declaration of a state of emergency!

The Church fulfils her legal duty of rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s; she renders what is due, nothing less – so why should the State demand anything more?

First published in Renovação (Vol. XXXVIII, No. 17, 1-15 Sept 2009, pp 7-8) under the title 'State Control on Church Property: Unwarranted, Perilous and Counter-Productive'. Reprinted with permission by The Navhind Times (20 Sept 2009) as 'Church Knows Best', in 'Panorama', Sunday magazine, p. 1.

Remembering Leonor

Paying homage to the dead is a cardinal civic virtue, an expression of gratitude that also helps to imbibe sterling values perhaps scarce in a new day and age. And this is what links us to Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, who was born on 24th May 1909 to Miguel de Loyola Furtado and Maria Julieta de Loyola. Married to Martinho António Fernandes, she was essentially a matriarch and a grand lady of the Fourth Estate.

Leonor was a career woman with a difference. A mother at 16, it was after this that she began writing in earnest, without letting this disturb her duties as a housewife. Her husband encouraged her to fight for her ideals through the weekly A Índia Portuguesa, and bore the brunt as Administrator of the Comunidades of Salcete, dogged as he was by controversy fuelled by a mix of personal vengeance and political vendetta.

Although Martinho eventually emerged unscathed, it was not easy for Leonor to weather those storms while she raised four daughters. A grandmother at 39, two years later she took over the said weekly, a family heirloom and historic mouthpiece of the political party called Partido Indiano, becoming the first lady editor in the whole of the Portuguese speaking world and in the Indian sub-continent too.

In 1951, she travelled to Portugal, the sole lady in a five-member media delegation from Goa invited to see the ‘mother country’. Portugal had then renamed its colonies ‘Overseas Provinces’, considering them an integral part of a far-flung Portuguese State. Leonor wrote about what had impressed her, not forgetting the meeting with Premier Oliveira Salazar, the Minister for Overseas Territories, Sarmento Rodrigues, and the pressmen with whom she spoke on different aspects of life in Goa.

Her trip of 1956 was marked by the publication of her first book, Salteadores da Honra Alheia na Índia Portuguesa (‘Assailants of People’s Honour in Portuguese India’), whose arresting title and explosive content led to its confiscation in Goa. While she wished to publicize the truth about her husband’s professional troubles, evil doings of prominent individuals and shady workings of many a public institution got exposed too.

Leonor was a champion of civil liberties by virtue of her journalism. As a proud descendant of one of Goa’s best known families involved in the civil rights movement, she took to it like fish to water. While critical of the administrative faults of the Portuguese regime, she was a moderate in her political aspirations, open to the ideas of decentralization and greater financial autonomy for Goa, and more importantly a zealous protector of the Goan identity, in the pre- as well as post-1961 regimes.

Her second book, Contribuição para um Mundo Melhor (‘Contribution for a Better World’) shows her love for Goa but does not camouflage her combative spirit. It has interesting reflections on the period spanning 1961-78; her missives from Portugal, Angola and Mozambique (August-October 1969); historical snippets about her newspaper; the story of the legendary José Inácio de Loyola Sr.; and photocopies of historic telegrams of the tumultuous days of September 1890.

Under the new political dispensation, her journal had to change its name to A Índia – just ‘India’! She was smart enough not to grudge this. But what provoked her ire was that the Comunidades had been given short shrift in a chaotic democratic state. In 1966, when interviewed by the redoubtable D. F. Karaka, Leonor fulminates against the police for searching her residence by night, looking for components of bombs and other subversive material used in the Vasco bomb case. Frustrated with their sole discovery, a book titled , her Indian passport was impounded and censorship was imposed on her paper.

The intrepid journalist declared that “her fight was against all governments who tried to deprive the people of civil rights and who imposed censorship, whether it was a Portuguese censorship or the censorship dictated by the Indian Government.” And some of her statements to the Bombay tabloid have a familiar ring even today: “The administration has gone rotten. In the (Goa) Assembly, the Opposition has accused the Government of nepotism, communalism, inefficiency and incompetence…. Laws have been passed without going into the constitutional right of the people,” she complained.

To redress her own grievances against the Government of Goa, she either met or wrote to Indira Gandhi every time. In her letter of 19th February 1966, she declared, “I believe in a Power above the powers of the world and in justice that comes, sometimes in time, at other times a bit late, in some manner or the other.” The restrictions were soon lifted, by a letter dated 13th May 1966, the significance of which day was not lost on Leonor: she was a great believer in the Message given on this day, half a century earlier, by the Mother of Jesus, when she appeared at Fatima, Portugal.

Leonor was truly blessed with a deep and empowering faith, or else she would not have endured as a career journalist until December 1975. And, not surprisingly, when the Angel knocked at her door on 8th January 2005, he must have found Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, at the ripe old age of 95, still steadfast in her principles and faithful to her people.

(Goa Today, June 2009)

Remembering Leonor: Editor Extraordinaire

To the dead it probably matters little whether or not they are remembered: having done their bit on earth they now belong to Eternity, where worldly honour and glory are of no consequence. But paying them homage is a cardinal civic virtue – an expression of gratitude for the valuable services rendered by them to the community, which also helps to imbibe sterling values that might well be scarce in a new day and age.

That is what links us to Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes on her birth centenary. Born on 24th May 1909 to Miguel de Loyola Furtado of Chinchinim and Maria Julieta de Loyola of Orlim, she was married to Martinho António Fernandes of Colvá. She was a woman of many parts but essentially a matriarch and a grand lady of the Fourth Estate.

Wife and Mother

Leonor – Lolita, in her close circle – was a person ahead of her times. She was a career woman with a difference. When the Panjim-based eveninger Diário da Noite (2nd May 1953) asked about the beginning of her occupation, she said, ‘I don’t remember clearly when I started writing. I know I became a mother at 16 and it must have been after this that I began writing in earnest.’

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

And reflect it did. As Administrator of the Comunidades of Salcete, Martinho Fernandes, a lawyer by training, was dogged by controversy, initially fomented by individuals who eyed his post, while later some of it was fuelled by a heady mix of personal vengeance and political vendetta, thanks to his wife’s plain speaking in the weekly A Índia Portuguesa. The incumbent emerged unscathed, through long and tortuous battles up to the apex court.

It must not have been easy for Leonor to weather those storms while she raised four daughters, managed the household chores and the family estates. But the years rolled by and, interestingly, at 39 years of age, she was already a grandmother! In 1950, when that venerable journal, a family heirloom and historic mouthpiece of the pro-native political party called Partido Indiano, founded by the Loyolas of Orlim, was almost folding up, it was born again with Leonor.

Journalist and Author

It was for the first time that in the whole of the Portuguese speaking world and in the Indian sub-continent as well a woman was at the head of a newspaper. This was only a natural consequence of having her father for a role model: apart from being a brilliant physician and political leader, he had edited A Índia Portuguesa from the year 1912 until his sudden demise in 1918, and his memory remained with Leonor for the rest of her days. She once said, ‘If destiny were not opposed to it, I would have studied medicine. I had a fascination for the medical profession, so as to positively spread the good to all. But I was born for something else – and I am a journalist only. I would have liked to be a physician and journalist.’ (Diário da Noite)

A year after assuming editorship she travelled to Portugal, the only lady in a Goan media delegation comprising Fr Manuel Francisco Lourdes Gomes, Álvaro de Santa Rita Vaz, Amadeu Prazeres da Costa and Luis de Menezes Jr. They had been invited for a month’s stay, to see for themselves what the ‘mother country’ was like. It was a public relations exercise by the Estado Novo, for in March that year the Government had passed an amendment to the controversial Colonial Act, renaming the colonies ‘Overseas Provinces’ and considering them an integral part of a far-flung Portuguese State. The change of nomenclature reinforced the one-nation theory, in a bid to counter global pressure against European colonization in the post-World War scenario.

The exercise paid dividends. Members of the delegation sent regular reports to their respective newspapers. On her return, Leonor wrote about what had impressed her, not forgetting the meeting with Premier Oliveira Salazar and the Minister for Overseas Territories, Sarmento Rodrigues. She had spoken to pressmen from continental Portugal and its overseas provinces on different aspects of life in Goa.

This was the first and surely the most memorable of her many visits abroad. Her official trip of 1956, on the fortieth anniversary of Salazar’s New State, was marked by the publication of her first book, Salteadores da Honra Alheia na Índia Portuguesa, (‘Assailants of People’s Honour in Portuguese India’). The curious little book’s arresting title and explosive content prompted the Portuguese Governor-General Paulo Bénard Guedes to have it confiscated on its arrival in Goa. While the author’s primary intention was to publicize the truth about her husband’s professional troubles, these are universalized, turning the book into a “repository of truths that make up our life in India.” The picture of a coconut tree and a cobra on its cover probably point to the coexistence of indolence and poison in our land. The evil doings of some prominent individuals and the shady workings of many a public institution are exposed.

Civil Rights Activist

Leonor was a champion of civil liberties by virtue of her journalism. As a proud descendant of one of Goa’s best known families involved in the civil rights movement, she took to it like fish to water. While critical of the administrative faults of the Portuguese regime, she was a moderate in her political aspirations, open to the ideas of decentralization and greater financial autonomy for Goa, emanating from the new Lei Orgânica do Ultramar, and more importantly a zealous protector of the Goan identity, in the pre- and post-1961 regimes. This was clear from her statement upon taking her seat in the legislative council of Portuguese India, in 1961: ‘Regimes fall, empires vanish, ideologies die, but the land remains, and we have to work for Goa to remain forever.”

Leonor was now left to fight life’s battles alone. She had lost her husband in 1960; and under the new political dispensation, even her journal had to change its name to A Índia – just ‘India’! She was smart enough not to grudge this, given the fait accompli of the Indian take-over of Goa. But what provoked her ire was that the Comunidades were being given short shrift, enough to have Martinho Fernandes turn in his grave.

In her second book, Contribuição para um Mundo Melhor, a tribute to her husband, printed on her last visit to Lisbon, in 1978, she addresses him on his life's interest, saying, "Do you see the state of our land today, how the Comunidades are faring, and how the land is groaning under injustice?" (p. 8) “Because our people are not rebellious and have not lost their sense of discipline and honesty, there has been no revolution yet,” she thunders (p. 14). It is clear that although she wishes to reconcile everything under a positive title (‘Contribution for a Better World’) nothing can camouflage her combative spirit.

Eye-opening Interview

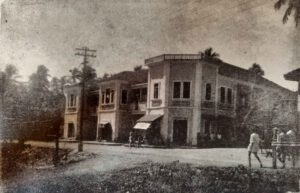

![]()

In 1966, The Current, a well known weekly published from Bombay, invited readers to send in entries for an interview competition to mark the publication’s 18th anniversary. Leonor submitted her experiences as editor of A Índia. As one of the four short-listed, she was interviewed by the redoubtable D. F. Karaka, who, curiously, twenty-three years earlier, had been mentioned as one of her favourite authors. It was a rendezvous of two editors sans peur et sans reproche…

The picture of Leonor that accompanied her “interesting entry” was considered “almost as threatening as the entry itself”. On the morning of the interview, a tornado was expected to blow into the newspaper office, bearing a flaming torch in one hand and a sword in the other. Although Leonor fulminated against the police for searching her residence by night, looking for components of bombs and other subversive material used in the Vasco bomb case, “the tornado from Goa was only a gentle breeze”, wrote Karaka. Frustrated with their sole discovery, a book titled Invasion and Occupation of Goa (National Secretariat for Information, Lisbon, 1962), containing world press reports on the contentious Goa Question, her Indian passport was impounded when she was on a visit to New Delhi and, back in Goa, censorship was imposed on her paper, with a heavy bond and two sureties made necessary to ensure “due performance of the restrictions”.

The intrepid Goan journalist stated that “her fight was against all governments who tried to deprive the people of civil rights and who imposed censorship, whether it was a Portuguese censorship or the censorship dictated by the Indian Government.” She especially decried censorship under a democratic set-up. “I wanted to publish in my paper extracts from Inside, which is a Swatantra Party paper. These quotations were cut out by the censors,” she said.

Final Years

Some of her statements to the Bombay tabloid have a familiar ring even today: “The administration has gone rotten. In the (Goa) Assembly, the Opposition has accused the Government of nepotism, communalism, inefficiency and incompetence…. Laws have been passed without going into the constitutional right of the people,” she complained.

While she made a case for the preservation of the Goan identity, showing her red-pencilled extracts of Nehru’s speech at Siddharth Nagar, Bombay, on 4th June 1956, to redress her own grievance against the Government of Goa, she either met or wrote to Indira Gandhi every time. In her letter of 19th February 1966, she declared, “I believe in a Power above the powers of the world and in justice that comes, sometimes in time, at other times a bit late, in some manner or the other.” The restrictions were soon lifted, by a letter dated 13th May 1966, the significance of which day was not lost on Leonor: she was a great believer in the Message that the Mother of Jesus gave on this day, half a century earlier, in her apparition at Fatima, a place Leonor visited on several occasions.

Her meetings with Mrs Gandhi are recounted in Contribuição, which also carries interesting reflections on the period spanning 1961-78; her missives from Portugal, Angola and Mozambique (August-October 1969), which though “innocuous” were responsible for her passport problems yet again; historical snippets about her newspaper; the story of the legendary José Inácio de Loyola Sr.; and photocopies of historic telegrams of the tumultuous days of September 1890.

Karaka had found it “heartening to see a woman in her 50s, who had been so disturbed by the turmoil of politics, still crusading for the rights of the people and still having faith in a Power above the powers of the world.” Leonor was truly blessed with a deep and empowering faith – or else she would not have endured as a career journalist until December 1975. She said, “I have great faith in Our Lady. Although I have been harassed in my life by the powers on earth, I have never cared or worried.” And not surprisingly, when the Angel knocked at her door on 8th January 2005, he must have found Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, at the ripe old age of 95, still steadfast in her principles and faithful to her people.

(Herald, 'Mirror', Sunday magazine, 24.05.2009)

Sonia - The Fado's New Fate

Sonia Shirsat is the Fado’s Lady Fate in Goa. On Valentine’s Day she swore her love for Portugal’s iconic melody. That the song has come to stay became obvious from the near-full Dinanath Mangueshkar auditorium that lapped up every bit of Mundo Fado II, Sonia’s first solo show on home turf.

Sonia’s voice is extremely well suited to the fado. Her talent first became evident at the ‘Vem Cantar’ contest (2002), through her superb rendering of Madre Deus’ ‘O Pastor’. Before long, ‘Barco Negro’’ sung by her also became a people’s favourite. And this time, a bright new ship – ‘M. V. Mundo Fado’, if you like! – dropped anchor in Panjim, from where it will again sail the Seven Seas.

Impressive is the line-up of fado greats that Sonia has performed with over the years. But more fulfilling must have been her own first solo concert, Mundo Fado, held in 2008, at Museu do Oriente, close to Alcântara docks, by the Tagus. She sang to a packed house, with guest artistes including Mestre António Chaínho, Manuel Leão, and Casa de Goa’s musical troupe, Ekvat!

Notice the poetry of that fabulous setting: the Orient, harking back to Goa; the proverbial waterfront, where the Fado originated amidst a sailor community; and the Tagus, from where all those intrepid ships once sailed “o’er seas hitherto not navigated… to seek out new parts of the world”….

So it was at Alcântara (‘the bridge’, in Arabic) that Sonia crafted her musical bridge with the fado world. Climbing onto the international stage is no mean task, especially for one not fully born into the genre. Sonia chose to cultivate it, chaperoned by her Lusophile mother Maria Alice Pinho, who belongs to a Goan generation raised on Portuguese music.

Mundo Fado II started off with an evocative instrumental medley by Sonia’s main accompanists, Flávio Teixeira Cardoso (Portuguese Guitar) and Pedro Miguel Soares Marreiros (Spanish Guitar) from Portugal. While they were at it, in walked Sonia draped in a designer gown and shawl. The backdrop was a quiet, understated, white with colour focus lights. Her first song was ‘Cansaço’ (‘Weariness’)… but needless to say both audience and artiste were zestful until the end!

There was a happy mix of familiar and not-so-familiar numbers. ‘Alfama’ (a tribute to Hotel Cidade de Goa’s restaurant of the same name where she is the lead artiste at the monthly ‘Noite de Fado’) was followed by ‘Amor de Mel’, Fado das Horas’, ‘Tive um Coração’, ‘Meu Amor Marinheiro’ and ‘Zanguei-me com o meu Amor’, among others.

Sonia’s show was marked by measured stylistic innovation. It featured the tabla (Mayuresh Dattaram Vasta), the flute (Marwino António da Costa) and the dhol (Santosh Sawant). And in a style all her own, the vocalist had none of that over-the-top emotionality of the Portuguese fadistas, nor did the tempo quicken as the show progressed; but she sang with passion, offering personal and historical snippets in her announcements.

Sonia infused the fado with new blood, giving the genre a fresh lease of life, and perhaps scope for another to emerge (in a Goan tradition of give and take, which people of good will must endorse). ‘Rua do Capelão’, a ‘modern fado Severa’, with flute and guitars, was a tribute to Maria Severa, 19th century Portugal’s best-known fadista. The popular ‘Cartas de Amor’ was backed by flute, tabla and Spanish guitar; and ‘Ave Maria Fadista’ by tabla and the guitars. It was most fascinating to see the Indian instrumentalists gel with their Portuguese counterparts in ‘Barco Negro’. The latter also took to ‘Doreachea Lharari’ and ‘Adeus Korcho Vellu Pavlo’ as fish to water.

Sonia hailed the mandó as ‘Goa’s fado’! And curiously, hiding behind the Konkani title of our best-known farewell song were Portuguese lyrics – the labour of love of a suave Goa enthusiast Manuel Bobone. The ensuing musical dialogue symbolised a confluence of the past and the future; and its melody is an apt signature tune for Sonia’s Luso-Goan musical experiment.

Mundo Fado II unwittingly commemorated the centenary of the modern fado, first recorded in 1910. And, putting behind its nearly five-decade long hiatus in Goa, Sonia gave a clarion call to young fado singers Danika da Silva Pereira, Manuela Lobo and Efigénia de Santana Miranda to rise to the occasion. She also expressed her camaraderie by inviting guest artistes Carlos Manuel Meneses and Allan Abreu (both Spanish Guitar), Daryl Coelho (Mandolin) and Franz Schubert Cotta (Portuguese Guitar) to be on stage with her. And early in the show, she recalled the musical moments shared with Orlando de Noronha and Dinesh K., both of whom couldn’t make it that day….

That’s ‘Team Sonia’ for you, poised to carve out a brilliant new fate for the Fado in Goa!

(Herald, Goa’s Heartbeat, 23 Mar 2011)

Love in Verse

VISIONS FROM GRYMES HILL, by António Gomes. Turn of River Press, 1994, 95 pp. Rs. 100

António Gomes, a eleven-year Goan veteran of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, is presently metamorphosed into a poet-philosopher. He examines the chemistry of suffering and joy, and attempts to decipher the mystery of life and death. After his wife died of cancer, in 1989, he thought he would never write poetry again. His inner world had been shattered by her departure. But God and Time are better healers than all our earthly physicians put together, and Gomes gradually came to terms with his loss and became whole again.

Visions from Grymes Hill is divided into two sections: “The Twilight Landscape” and “Poet’s Den”. In the first, the poems are more personal, reflecting his intense pain on the death of Marina. Gomes feels helpless that as a doctor he could not save her life. As he confesses in the Preface, “a doctor, a scientist and a heart specialist, I was engrossed in the miracles of Science. Yes, indeed! Science for me then was the one god I knew and understood above all gods. I was angry at this god for abandoning me. This god through whose intercession I had often mended the hearts of many men and women.”

Death laid its icy hands of her like an untimely frost upon the sweetest flower on all the field. The poet, unable to save her, is now in search of her. The poem “Visions” is a series of dreams reflecting this search, if not to find her – to find the answer. Born into a Roman Catholic family from Loutulim, Gomes now presents himself as an eclectic philosopher travelling through Hindu and Buddhist mythologies to find “the noble truth of the cessation of suffering” through “renunciation”.

The sad and humdrum life of a lonely man is reflected in the tone of some of the verse; but the sombre atmosphere turns to light whenever the poet chances upon the understanding of the mystery of life. Then he transcends his troubles and marvels at the myriad colours of human nature. His magnanimous heart looks upon the suffering of the “beggar and the hungry child”; his singing soul revels in music and dance as he draws the fine “portrait of a jazz pianist”, and Stan Getz.

Despite the magical confusion of his inner world, Gomes does spare a thought for Tiananmen Square and the Berlin Wall, communist dictatorships and Mikhail Gorbachev. All this is woven into his sensibility but he compulsively returns to “the image of my dear sick wife/Falling, rising, struggling/ Beautiful and hopeful to the very end”. Beautiful and hopeful, which is why even while a window closes on him with loss and sorrow another opens up with joy and hope. And as he turns his back on the images of the fateful year of 1989 “I welcome 1990, dancing with Tania, my only child”.

The “Poet’s Den” is an epic poem in which we follow the poet’s journey to disparate worlds and cultures. On seeking inspiration from the muse to write an epic, the poet is taken to a den where he encounters dead poets, ancient and modern. We are thus privileged to listen in on his intimate and far-reaching conversations with the great Bards from Dante, Goethe, Rilke, and Camões to Whitman, Tagore and Neruda.

The thematic range of this Section goes from the personal and religious to the social, economic and political. The issues reflect the events of the late 1980’s and early 90’s, “new challenges that have the immense potential of changing our world and our civilization”. Curiously, in these poems, written in the form of dialogues, Gomes blends his own poetry with that of the bards he encounters.

In Visions from Grymes Hill, which is his residence at Mount Sinai, António Gomes comes out as a man with the heart of a physician and the soul of a poet. Most touching is his line in the Preface: “I hope that those who read this book or parts of it will find these poets healing”. Witness the selflessness, the devotion, and the magnanimity of a fine doctor and sincere husband who invites us to partake of the pathos and passion of being fully human. The reader cannot help wishing that the poems have been cathartic for the writer himself.

(Herald -The Illustrated Review, 1-15 Sep 1995)