Tiklem

Conto de autoria de Willy Goes | Traduzido do concani, por Óscar de Noronha*

“Ó burro, pense um bocadinho, seu animal! Ó seu búfalo, faça uso do seu bom-senso, se é que lhe resta algo! Ó seu boi, estão a desmanchar-se todas as propostas de casamento que a sua irmã recebe. E sabe quem é a causa disso? Você!” disse a mãe ao Brikston, dando-lhe um forte puxão de orelhas.

Brikston reagiu com tanta raiva, difícil até de imaginar. E por quê? Não porque tivesse sido chamado burro ou boi, mas porque a mãe lhe deu um puxão de orelhas.

“Não sou rapazola de dez anos, para estar assim a dar-me um puxão de orelha,” disse o filho.

Brikston tinha vinte e oito anos… não se sabendo se se devia considerá-lo moço ou homem. Era bem instruído, mas a sua bebedeira lhe estava a dar cabo da vida. Era dono de um táxi, mas em vez de ele o conduzir, para melhores lucros, deixando o táxi a cargo de um motorista, ficando ele o dia todo sentado a beber na taverna. Este não dava conta do dinheiro ganho; e, por sua vez, o dono contentava-se com a receita desde que lhe assegurasse a sua garrafa.

“Ó mãe, com esse forte puxão de orelha, agitou a minha cabeça e me causou muita raiva! Por isso, pare de falar, antes que eu expluda como um vulcão,” disse em tom de ameaça.

“Ó, você e a sua raiva, meto-os numa lata. Ora, você é bêbado. Não temos medo da cobra feita de folíolo nem da fúria de um bêbado. Oiça agora o que eu lhe tenho a dizer. A sua irmã recebeu uma proposta de casamento. O noivo é empregado do Estado. São quatro irmãos; e este é o mais novo. São três rapazes e uma rapariga. A irmã é tikli – nasceu após três rapazes. Os dois mais velhos já são casados. O noivo está resolvido a não casar enquanto não case a sua irmã,” disse a mãe a Brikston.

“Ó meu Deus! Então, por ser tiklém, esta coitada vai ficar solteira. Ninguém casará com ela; nunca se realizará o seu casamento nem o do irmão. Rejeite a proposta, e veremos outro noivo para a nossa Florishka,” sentenciou o Brikston, como se não houvesse dificuldade alguma em se achar noivos.

“Ó seu boi, quem vai achar outro noivo? Porventura, estarão eles à venda no mercado? A família convidou-nos a ir hoje à sua casa. Diz que enquanto a irmã não achar noivo, ele quer ficar seguro de noiva. Eu estou já velha, é sua responsabilidade casar a sua irmã. Vá com ela à casa do rapaz,” ordenou-lhe a mãe, acrescentando: “E não se embebede. Se não, pode ele rejeitá-la por ser irmã de bêbado. É o que tem sucedido em casos desses.”

“Bom, farei como a mãe quer. Vou levar a Florisha à casa dessa gente; e também verei se a irmã do rapaz encontra noivo,” disse Brikston, tomando sobre si a responsabilidade de casar a irmã.

Brikston e Florishka chegaram à casa do potencial noivo. Foram bem recebidos, sentaram-se e estiveram a conversar. Stanzar, o noivo, era funcionário público do Upper Division Clerk - UDC. Não tinha vícios de fumar nem beber. Pela conversa, via-se claramente que Stanzar se simpatizara com Florishka. A sua irmã constituía o único impedimento: ele não casaria antes de ela se casar.

“Onde está a sua irmã? Podemos conhecê-la antes de partirmos?” perguntou Brikston a Stanzar.

“Sem dúvida, não deixem de falar com ela antes de partir, e vejam se lhe acham noivo. Mas só vos previno: ela é tiklém: nasceu a seguir a três irmãos,” explicou Stanzar. “Trishka… Trishka, anda cá.”

Vindo ao encontro dos hóspedes, Trishka cumprimentou-os com uma risada. Era bem-parecida, de tez clara, de estatura mediana. Tinha sempre um riso na cara e porte jeitoso. Era de encher a vista. Logo que a viu, Brikston ficou estupefacto, preso ao seu lugar, porém, como se a levitar. Dentro do seu peito, o coração palpitava sem parar.

“É esta a sua irmã? Como é seu nome?” perguntou Brikston, embora apenas há uns momentos Stanzar a tivesse chamado pelo nome.

“Trishka. O meu nome é Trishka. E o seu?” perguntou suavemente.

Ouvindo essa voz tão doce, Brikston levantou-se e, aproximando-se da Trishka, disse, estendendo-lhe a mão: “O meu nome é Brikston. How do you do?”

“Nice name. I am fine, thank you.” respondeu Trishka, apertando a mão.

Após mais dois dedos de conversa, Brikston levantou-se, passou uma vista de olhos por todos, e dando uns passos em direcção de Stanzar, despediu-se com um aperto de mão.

“Não sei se você gostou ou não da minha irmã, e nem me preocupo com isso. O facto é que gostei da sua irmã, Trishka. Poderíamos conversar mais sobre o assunto, o mais cedo possível, em minha casa. Por hoje é só. Vamos embora. Mog asum di.” E dito isto, partiram.

“O quê, seu bêbado! Você deu a palavra a essa tiklém? Antes disso, devia pelo menos consultar-me, seu animal! Não sabia que ela é tiklém? Quem se casa com uma tiklém?! Uma vez boi, sempre boi.”

Dito isso, a mãe de Brikston ia dar-lhe um puxão de orelha, quando ele, segurando a sua mão, impediu-a.

“Diga o que quiser, mas não me puxe a orelha,” disse Brikston terminantemente à mãe, apontando o dedo no ar. “Isso de tiklém-biklém não me interessa. É tiklém não por culpa própria! Coitada, nasceu depois de três irmãos. Que mal há nisso? Não presto atenção a essas superstições. Se isso de ser tiklém-biklém lhe interessa, isso é lá consigo. Vou casar-me com Trishka, and that is final!” disse Brikston firmemente.

“Tens alguma coisa a dizer, querida, a respeito da decisão do nosso bêbado?” perguntou a mãe, dirigindo-se à Florishka.

“Mãe, em primeiro lugar, pára de lhe chamar bêbado, boi, burro… Tu mesmo lhe deste o nome de Brikston, então porque lhe chamas de bêbado, boi, burro…. Quanto mais lhe chamares de bêbado, mais ele beberá. Chama-lhe pelo nome próprio, com carinho, e vê lá como ele vai mudar. Em segundo lugar, já que ele escolheu noiva, deixa-o casar com a rapariga. Isso de tiklém-biklém é cantiga.”

É claro que a mãe não gostou do que ouvira da boca de sua filha Florishka.

“Já percebi. Disse o rapaz não casará sem que a irmã fique arrumada: é por isso que tu estás a apoiar o teu irmão! Se por casar com a tiklém lhe vier a acontecer algo, seja a ele ou a nós, serás tu responsável. Percebeste?” disse a mãe, furiosa.

Correram os dias no meio dessa polémica, mas Brikston, sempre intransigente, casou com Trishka. Um mês antes, haviam casado os respectivos irmãos, Florishka e Stanzar.

O casamento de Brikston com a tiklém provocou grandes prejuízos a muitos co-aldeãos, ou seja, às tavernas, pois, Brikston parou de se embriagar e nem sequer suportava o cheiro a álcool. Mais, ficou desempregado o motorista do táxi, pois Brikston tomara-lhe as rédeas, vindo a ganhar rios de dinheiro. Aos poucos, teve meios para adquirir mais dois carros de praça, de modo que, em três anos de casado, já tinha três carros em casa, um conduzido por ele próprio e os outros dois entregues a motoristas da sua confiança. Estes prestavam contas regularmente. Além disso, Brikston consertou a sua casa e investiu dinheiro no banco. E assim se tapou a boca da mãe.

Ao fim de cinco anos de casamento, o casal tinha já três filhos. E estando grávida pela quarta vez, a mãe de Brikston aguardava a sua hora, ela que há tantos anos esperava que lhes viesse algum azar por via da tiklém. Efectivamente, nasceu-lhes uma menina, uma nova tiklém.

“Já viu isto? Já lhe tinha prevenido para não casar com a tiklém. Veja como a tiklém nos trouxe uma nova tiklém, como não podia deixar de ser... e quem casará com ela?” – desafiou a mãe ao Brikston.

“Ó mãe, esta criança, coitadinha, acaba de nascer. Quando ela crescer e estiver na idade de casar, encontrará um outro como eu; e tal como a presente tiklém me trouxe grande felicidade, também esta nossa fará o mesmo. Entretanto, a mãe faça votos para que chegue a ver a felicidade da recém-nascida.”

* Nota do Tradutor: Embora a língua concani modernamente se escreva sem acentos ortográficos, vai acentuada a palavra tiklém só para indicar a pronúncia adequada aos leitores portugueses.

Sobre o Autor

Willy Goes (1963-) é contista e autor de nove livros, sete em concani e dois em inglês. Actualmente é o Director do Goa College of Art. Foi membro do Conselho Consultivo do Concani na Sahitya Akademi, Nova Delhi. Apresentou trabalhos em seminários e ganhou prémios pela escrita criativa e fotografia.

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisboa), Série II, No. 23, Julho-Agosto de 2023, pp. 57-62 https://rb.gy/8qj52

Ligeiramente editado neste blogue.

Banner: https://rb.gy/4cw48

The Migrant

Short Story by Maria do Céu Barreto, originally written in Portuguese as "O Migrante". Translated by Óscar de Noronha, in Under the Mango Tree: Stories Stories from Goa © Fundação Oriente (Goa).

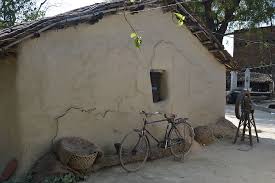

Vinod just couldn’t sleep. He tossed and turned in his bed and lay on his back again, just unable to doze off. He thought it better to keep his eyes open and treasure in his heart the little room he shared with his brothers, all of them younger than him. Through the gaps, the faint light of dawn was already visible inside the hut. He knew it was time to be on his feet yet kept lazing in his straw bed for a few minutes, thinking about his impending adventure.

What would Goa, where he was going to hunt for a job, be like? He was told by his country-cousins there that the land was bathed by the sea and its blue waters mirrored the clouds. There were long, seemingly endless, beaches of white sand. He rejoiced at the thought that it must be a very beautiful location indeed. He had seen the sea in the movies; now he would get to soak in its waters.

But then, he wasn’t going to Goa for its beauty. A job, however modest, is what he was looking for. He was gutsy and painstaking; work never intimidated him. Even as a little boy he had helped out in the fields. His father had tried to make sure his children would have a decent future; he had taken a bank loan and spent it all on those fields. But alas, the soil had been ungrateful; the gods did not help, despite the family puja every morning. The hot sun had burnt up all the plantations that he had seen grow. The rain gods had abandoned them. Only wealthy farmers had managed to live through the drought: they had the money for irrigation and to buy electric pumps to draw groundwater. Debts were mounting with every passing month, and one day when he came home, he found his father's body hanging from the ceiling. Unable to pay off the loan, he had committed suicide, like many other peasants in despair.

But then, he wasn’t going to Goa for its beauty. A job, however modest, is what he was looking for. He was gutsy and painstaking; work never intimidated him. Even as a little boy he had helped out in the fields. His father had tried to make sure his children would have a decent future; he had taken a bank loan and spent it all on those fields. But alas, the soil had been ungrateful; the gods did not help, despite the family puja every morning. The hot sun had burnt up all the plantations that he had seen grow. The rain gods had abandoned them. Only wealthy farmers had managed to live through the drought: they had the money for irrigation and to buy electric pumps to draw groundwater. Debts were mounting with every passing month, and one day when he came home, he found his father's body hanging from the ceiling. Unable to pay off the loan, he had committed suicide, like many other peasants in despair.

Vinod rose from his straw bed resolutely. He sat in the doorway to take in the morning air. He looked around. It was all arid. There was no other way out; he had to set off, to help his mother support the little ones, who were still asleep. The school was two kilometres away and they walked to and fro every day. Poor little chaps! Mother tried to persuade him to stay on. She needed him; it would be hard to bear it all alone. He put across his point of view in the best way he could, asking her to pray to the gods as she always did, without ceasing. And then, no more hesitation; his fate was sealed. But today he had still to fetch water from the well – his last chance to help out. With the little liquid left over from the previous days, he had a wash and, as usual, went to the bushes to answer Nature’s call. Toilets were a rare sight in the rural set-up. All governments had promised to build lavatories; those were only election campaign promises, forgotten as soon as the aspirants rose to power.

It was still very early in the morning, yet he wasn’t among the first ones to turn up at the well. There was already a queue for men and another for women. The menfolk usually drew the water and the women headed home with those pots held on their heads. Vinod was glad to see this line-up of women draped in multihued saris; they talked, giggled and looked askance at the boys. Lakshimi was there too. She had captured his heart and, by the looks she gave, his passion for her seemed to be reciprocated. How good it would feel to be back from Goa with money and to marry her! He had heard of many such success stories. He too would do well; he sensed success from deep within his soul.

It was still very early in the morning, yet he wasn’t among the first ones to turn up at the well. There was already a queue for men and another for women. The menfolk usually drew the water and the women headed home with those pots held on their heads. Vinod was glad to see this line-up of women draped in multihued saris; they talked, giggled and looked askance at the boys. Lakshimi was there too. She had captured his heart and, by the looks she gave, his passion for her seemed to be reciprocated. How good it would feel to be back from Goa with money and to marry her! He had heard of many such success stories. He too would do well; he sensed success from deep within his soul.

Back from the well, he saw his mother preparing breakfast at the firewood stove. She handed him a plate of roti and bhaji. He ate every bit, for he couldn’t say when his next meal would be. By now his siblings had woken up and were gearing up for school. Vinod thought of taking the eldest one with him to Goa one day, and then maybe the whole family! At construction sites there was always employment for everyone.

The train was due to leave at noon, and it would be two hours before he got to the station. He thought it better to start out before he had a change of mind. He had written to some of his village friends in Goa but hadn’t heard from them. He hoped at least one of them would pick him up from the station; it would be a relief if they got him accommodation, even if only for a week. His mother handed him whatever she had saved up for emergencies – a thousand rupees, quite a fortune, he thought. He tucked it away, picked up his suitcase, and humbly kissing his mother’s feet bid her farewell.

“God be with you, my son,” said his mother, embracing him. “Krishna will protect you.”

He couldn’t pluck up his courage to hug his siblings, who had started to cry. He patted them on the head and left for the station. He turned round before the last bend of the road: his mother and brothers were there waving at him. He paused for a moment and waved back. He was all alone now.

Vinod heard the whistle in the distance. The train had arrived, a little late as usual. The passengers stood where they thought their wagons would stop and were ready to pick up their suitcases. Travelling as he did, third class, Vinod had no reserved seat. He had to be in readiness, too, as it would now turn quite messy with people jostling for the best of places. As soon as the train halted, he picked his suitcase and dashed off to grab a good seat, and grab one he did. He placed his luggage on the rack and stretched his legs. He was very tired. Lack of sleep, anxiety, tension... Now he was sure to drift off. A few minutes after the train was in motion and had gathered speed, Vinod leaned on the headrest and shut his eyes.

He could not say how long it had been – maybe all night and a good part of the day – but when he woke up he found the landscape had changed. He tried to strike up a conversation with his fellow passengers.

“Have we reached?” he asked a young man who was going to Goa, or so he thought.

“Not yet. It’s still a little too early. We will get there by evening,” said the young man.

He wished to ask him a few more questions about Goa but noticed that he had dozed off. With a few more hours to go, he thought of walking up and down the corridor but feared for his seat. Patience! He would have to remain seated there throughout. He noticed some passengers preparing to eat their home-packed breakfast and, famished as he was, avoided looking at the foodstuff. Just then, a co-passenger invited him to share his breakfast, an offer he gladly accepted.

What a long journey it was! He closed his eyes again, knowing well he would not get even a wink of sleep amid the bustle of hawkers. The train had halted at a station and the peddlers were crying their wares – food, fruits, artefacts, and other items. They did everything to draw the attention of the passengers and win them over. Vinod smiled. He hoped to have Lakshimi by his side on his next trip. A slim and pretty girl she was, whose long hair, charcoal-black eyes and tanned skin made his heart stop. He had not bid her goodbye, for in the village boys seldom talked to girls without their parents' permission. And badly off as he was, they would ignore him. But everything would change when he returned with his pockets stuffed with cash. Where would he celebrate his marriage? Back at his native place for sure, in keeping with tradition. All expenses would be borne by the bride's parents. He would not ask for a dowry; he knew that her parents did not have the means and he had no intention to get them into debt, like many families did…. But would she wait for him until he came back?

Vinod fell asleep, lulled by these thoughts and unmindful of the noise. On waking up, all he saw was lush green countryside and water, water, water everywhere. There were lakes and rivers, and as the train carried on, he saw waterfalls too. He had never encountered anything like this before; he was sure it was Goa. Half an hour later he felt the train grind to a halt. The whistle blew; they were at Vasco da Gama, the port city of Goa.

Vinod fell asleep, lulled by these thoughts and unmindful of the noise. On waking up, all he saw was lush green countryside and water, water, water everywhere. There were lakes and rivers, and as the train carried on, he saw waterfalls too. He had never encountered anything like this before; he was sure it was Goa. Half an hour later he felt the train grind to a halt. The whistle blew; they were at Vasco da Gama, the port city of Goa.

A motley crowd welcomed their friends and relatives. Vinod felt his ears numbed by the numerous languages he heard: it was a real Babel. He even heard some words in his language! Was it his friends? He saw none; it was hard to locate people amidst the chatter. He let the other passengers exit first; he was not in a hurry. Then, all of a sudden, someone called out his name.

“Here, here we are!” Turning around he spotted Rama and Vishnu, his childhood friends. A strange joy seized his heart: he was no longer alone. They hugged him; they were thirsting for news from their land, family, friends, but Vinod, not in the mood for all that, promised to field questions a little later. He noticed that they looked very different, well dressed and cheerful as they were. Obviously, life had not treated them badly. He was happy for them.

“You’re staying with us tonight! Mother is waiting for you. Let’s see, if you like, you can even stay longer, until you get a job,” said Rama.

Vinod was thrilled. He did not know what to say.

“How are we going? Shall we take a rickshaw?” he asked.

“No, no, we’ll take our motorbikes.” Vinod was amazed. Their bikes? How did they manage to buy bikes? Questions and questions that would have to wait for answers…

On arriving at Rama’s house, Vinod found the pleasant aroma of food engaging his senses. It was a small house compared with the others around there, but it had electricity, piped water and even a gas stove – luxuries for people from poor, parched areas.

“Miss our land and our friends so much!” Rama exclaimed at the post-dinner chat. “No doubt it’s great out here, you know! Communities live in peace; no one interferes with you. Yet, it’s not the same as your own land. It’s a different culture; language and food are so different. To fit in, we’ve had to learn the local language, so much so that many of us speak better than the locals do!”

“And do the locals treat you well?” inquired Vinod.

“Well, they bear with us. They feel we are robbing them of their jobs and that in future they’ll be outnumbered by the migrant population. Maybe they will; I don’t know. However, they shouldn’t forget that we’ve helped them develop this state. We do all the hard work, so I think we’re a part of this land, although they don’t think so. They are proud of their half-Western culture and dub us ghanti and shower insults, which we pay no heed to… To make sure we do well, we must avoid squabbles.”

“And why can’t they get those jobs?” Vinod retorted.

“They can, except that they don’t want to work hard; they try to find jobs that won’t have them dirty their hands. The educated lot opt for the civil services or private company jobs. They think this fetches them better security and better respect. And those who don’t get such jobs or aren’t happy with what they have, simply migrate. I know families and families that have migrated.”

“They can, except that they don’t want to work hard; they try to find jobs that won’t have them dirty their hands. The educated lot opt for the civil services or private company jobs. They think this fetches them better security and better respect. And those who don’t get such jobs or aren’t happy with what they have, simply migrate. I know families and families that have migrated.”

“Where do they go?”

“Don’t ask! Maybe Dubai, England, Canada… I think there are Goans scattered around the world.”

“Are they happy?”

“Hard to say…. They earn better and enjoy a better quality of life… And who knows, maybe they even suffer humiliations like we do and are treated as second-class citizens.”

“And they sure miss their land,” observed Vinod.

“Of course, they do. They celebrate their respective village religious festivals, cook typical Goan dishes and even have exclusive Goan associations, where they meet regularly. You see, no one can forget their own little land.”

“So they are like us!” exclaimed Vinod.

“Yes; only that we are migrants and they are emigrants.

”Vinod was very tired and, by now, dying to go to bed, but the conversation was so interesting that he decided to linger.

“I don’t understand how you guys have all these things at home, and bikes too.”

“That wasn’t easy. We had to work hard. Of course, we have to also be in the politicians’ good books. At election time they grant whatever we ask for, in exchange for votes. The larger the family, the greater the bargaining power. For instance, you are alone and won’t get much, but if you tag your family along, you’ll get much more.”

“And how did you secure this place?”

“That wasn’t difficult. In fact, one has only to build a hut in some vacant space, live there and in time government legalises everything.”

“Incredible!” said Vinod. “I think coming here was the right thing to do. I’ll bring my family here as soon as I can.”

Just then they overheard some commotion outside. “What’s that?” said Vinod. “Who’s fighting?”

“Not to worry! That’s Vishnu; he drinks every night and creates a racket in the neighbourhood. He spends all his earnings on drinks. He has three children, and, to support the family, his poor wife works at several households. This is a real hazard in Goa. Alcohol and drugs are easily available. There’s a bar every few hundred metres. That’s a great temptation. Make sure you don’t fall into this trap, for then it’s tough to get out of it. We’ve come here to make money and have to focus on that.”

“Rama, thanks for the warmth and advice… I won’t do any such thing. I’ve suffered enough back home; I’ve seen misfortunes caused by the lack of money. The first thing I’ll do now is look for a job.”

“I’ll help you if you like. I know the builder of the nearby constructions. If I recommend your name, he’ll find you a job.”

“Yes, please do.”

Vinod thanked him once more and went off to bed. The morrow would be another day. So far so good! The future was in God’s hands. He smiled and fell asleep with these thoughts. Was he dreaming of Lakshimi?

Glossary

Roti: An Indian unleavened flatbread made from wholewheat flour and water that is combined into a dough. It is rolled out and cooked on a griddle over a flame.

Bhaji: A vegetable preparation

Puja: Prayers

Ghanti: Lit. From across the ghats. Coll. Outsider. A derogatory term directed at people, especially non-Goans who come to Goa, whether they are from across the ghats or not.