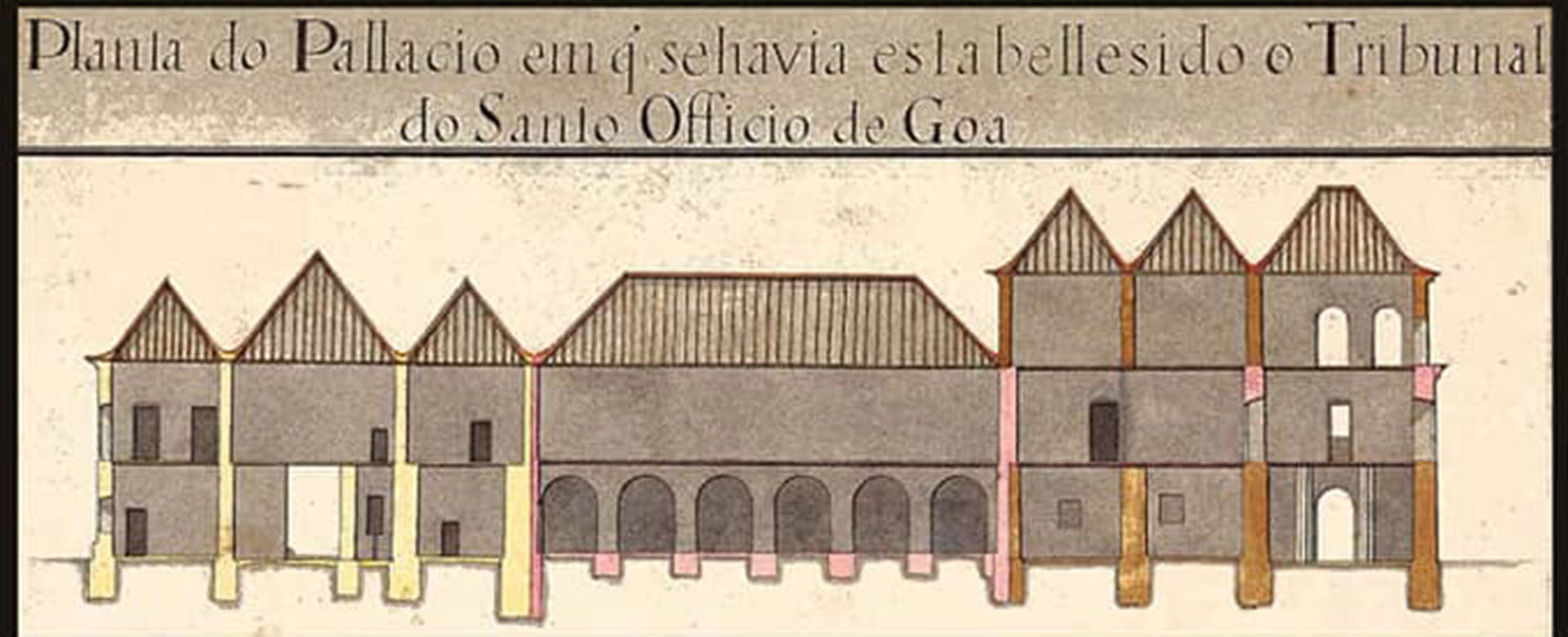

Why the Inquisition in Goa

At Instituto Camões, Panjim, Professor José Pedro Paiva of the University of Coimbra provided a lucid rationale for the establishment of the Tribunal of the Inquisition in Goa (1560-1812). His talk was titled "Reasons for the Founding of the Goa Inquisition in 1560". He stated, among other things, that even prior to the arrival of St Francis Xavier the Religious had endeavoured to establish the Tribunal in Goa.

For my part, convinced that no serious student of history should depend exclusively on Charles Gabriel Dellon's much-quoted account titled Relation de l'Inquisition de Goa (1687) and Bombay-based A. K. Priolkar's expedient interpretations of the Frenchman's allegations, I asked the erudite Professor where one would find fresh archival sources to counter their claims. He pointed to the Portuguese and Brazilian archives.

Without a doubt, the Tribunal, like every human enterprise, had its shortcomings; but having said that, by no means do Dellon and Priolkar deserve a clean chit. While the testimony of the former, who was tried and incarcerated by the Tribunal, is largely suspect, the latter's narrative fails to contextualize the institution, and his vitriolic language hardly behoves a researcher. It is curious to note that his work appeared in the year 1961, a watershed in the history of Goa and Portugal.

It is a pity that there has hardly been any comprehensive study of the Goa Inquisition, particularly in the English language. And alas, just as a big lie told frequently enough is finally believed, unsuspecting readers have found themselves trapped in a web of lies regarding the nature and purpose of the Inquisition. It is heartening that a younger crop of researchers has been shedding fresh light on the subject and overturning previous findings or misplaced conclusions.

Meanwhile, as the matter in question often boils down to the number of deaths at the stake, I was keen to know details of the same. The exact figure will never be known, since the relevant papers are unavailable, for reasons too complex to mention here. However, Professor Paiva authoritatively stated that, based on the lists of names available in Lisbon, the number of trials held in Goa, over a period of 250 years (1560-1812), are reckoned at 14,000 and the convictions at 800, the average thus being 3.2 deaths per annum.

Comparisons may be odious, but can we overlook the odious crime of human sacrifice perpetrated in Indian society outside the borders of Goa during that same historical period? Some of them had religious sanction, others were committed arbitrarily, but none gave any scope for self-defence or mercy. Similarly, who can deny that the number of convictions by criminal courts far exceeded the inquisition tribunal's annual average of convictions?

Finally, those numbers pale by comparison to the political and other inquisitions at work in the twenty-first century, many of which - please note - do not have even the semblance of a tribunal or a fair trial. Hence, a sense of history and fair play are a must to understand the rationale behind the Inquisition tribunal set up in Goa way back in the sixteenth century.

A Life in Translation

Quasi-Memoir-1

I was clueless as to 30 September, International Translation Day, instituted two years ago. I got the lowdown from that enterprising, Herald journalist Dolcy D’Cruz: for the purpose of a feature to mark the occasion, she'd sought to know what translation meant to me and how I went about my activity.

‘Translation is a magical thing,’ I said to her, almost instinctively. ‘Not only does it help spread information and speed up business across the globe, it promotes cultural understanding.’

At the back of my mind were Tolstoy and Dostoevksy, Verne and Dumas, Anderson and Grimm, authors whose native languages I didn’t know. And I shed a tear for those who had to depend on renderings of Shakespeare, Dickens and Twain, and why not, Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie and P. G. Wodehouse. I was lucky to read them all in the original, as I was, when it came to my father’s recommendation of a Portuguese staple diet: Júlio Dinis, Garrett, Camilo, Eça, Ramalho, Aquilino, for a novice; and my additions: Pessoa, Torga, Namora, Agustina, Lobo Antunes, and Saramago (with a pinch of salt).

Literary translations have made the world richer. And it’s not literature alone that has depended on translations; even the most disparate subjects like history, medicine and everything in between have benefited from them. If in the early twentieth century, seminarians in our archdiocese had to depend on Latin texts, it wasn’t only because that’s the official language of the Church; there were no translations available in the vernacular!

Even more picturesque was my doctor aunt’s story about the use of French manuals at the Goa medical school, as late as the 1950s: students had soon cultivated the art of reading them aloud in twos or threes, and straight in Portuguese. That was magic!

Early days

As aural memories came gushing, I began to realize that translation had indeed been an organic part of my life. As a child juggling several languages, from Portuguese and Konkani at home, to English, French and Hindi at school, oral translations happened almost as a matter of course. I would reproduce in Portuguese information that I’d received in English, and vice-versa. Mixing of lingos and literal translations were a big no-no, whereas idiomatic language was warmly encouraged.

Yet, translation per se was never the main concern; the accent was on reading good literature and relishing good conversation; it was about having a dictionary at hand and looking up the meaning of an unfamiliar word; it was about finding le mot juste. It was no cakewalk but, looking back, the long walk was so worth it. And a job well accomplished always translated into joy.

After my father’s remark, ‘Languages are an asset; master them while you’re young,’ the next best thing that stuck in my head was Bacon’s famous quote: ‘Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.’ This was like a command from on high. Or for that matter, F. J. Sheed’s dictum that ‘… minds feed on minds, you cannot nourish your mind with a chop,’ struck me as very sensible.

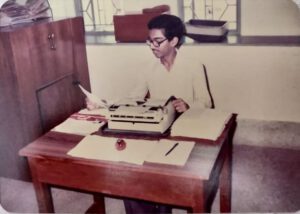

After handling English texts, ‘ex officio’, on school days, I would spend bits of late Sunday mornings decoding Portuguese texts under my father’s tutelage. By the end of high school, I had begun devoting an hour or so to transcribing All India Radio afternoon news bulletins for O Heraldo. And why? Now it just seems so funny: I’d found this arrangement vital since Goa’s first daily, which was on its last legs, no longer subscribed to news agencies and was starving for news. I also thought it would reassure my father who, after retiring prematurely, lent a hand at the paper – for the love of the Portuguese language and practically for free.

In the public domain

That happened to be my first stint with translation outside the domestic sphere. I didn’t think any good would come out of all that. But, three years later (1983), when I least expected it – I was in the first year of college – the then Jesuit priest Teotonio R. de Souza invited me to work as a research assistant at the newly established Xavier Centre of Historical Research of which he was the director. My task was to create summaries in English of the Mhamai Kamat papers written in Portuguese and French. I was also pleasantly surprised that he’d entrusted me two of his research papers for translation. That we argued playfully about his views is quite another matter entirely!

After my MA at the University of Bombay (1985-87) and a language and culture course at the Universidade de Lisboa (1988), I had a short stint as a lecturer in Portuguese at Dhempe College, Panjim, chiefly, to replace my father who was down with malaria. After a few months, I hesitantly took up an interpreter’s job at the Embassy of Brazil, lured by the national capital. On arriving there, however, I was stunned to see that I would be assisting an eighty year old: Pylades Prata Tibery, a Brazilian national of Greek and Italian ancestry, introduced himself as a ‘juiz de gado’ (cattle judge).

Tibery and I crisscrossed the subcontinent, by road and rail, trailing the Nellore buffalo – a breed that, according to the garrulous old man, Brazil had imported from India in the early twentieth century. Our activity was interspersed with a generous exchange of notes on European and Brazilian Portuguese. While the English of his school days was amusing, even more so were his colourful descriptions of ‘convivial society’ expressed in his native Brazilian.

Well, I could hardly be buffaloed by a more outlandish task even if handsomely paid, as indeed I was. It marked the beginning and the end of my honeymoon with translation/interpretation as a full-time job... On my return to Goa, I took up teaching as a career. After the initial hiccups, I found fulfilment in interpreting my students’ thoughts and feelings, and translating their ignorance into knowledge, their anxieties into hope, and their ambitions into reality! Translating and interpreting could now only be side gigs, mostly to oblige friends and family. For instance, I liaised at a couple of wine festivals and carried out humdrum legal translations, among other things. Even these I could no longer endure when I finally had my eyes set on translating literary, historical and spiritual texts. That would surely be a balm to my spirits.

Literary translation

Sometime in 1995, a brief encounter with Editor Arun Sinha of The Navhind Times provided that go. Keen on setting up a literary page to step up his paper’s Sunday magazine, ‘Panorama’, he suggested I work on Goan short stories written in Portuguese. I did produce quite a few translations, but alas, inevitable changes on the home front constrained me to discontinue the series.

But in spite of everything, mine has continued to be a life in translation, of which the Herald article gives a glimpse (see the link below).

(To be continued)

When I met Abade Faria...

I lived next door to Abade Faria for thirty years. As a child, I remember asking my father what that name meant. Keen on passing on informatio n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

Abade Faria is that very striking statue in the heart of Panjim. I couldn’t have met the man himself: José Custódio de Faria was born in 1756, at his mother’s house in Candolim. His father was from a less known village, Colvale. As I came of age, I learnt that he was the son of a priest and a nun… Hold on! They were ‘normal’ people, Caetano Vitorino de Faria and Rosa Maria de Souza, who got married, had a child, and then broke up. The father took holy orders at the then Chorão seminary while the mother joined St Monica, Asia’s largest nunnery, at Old Goa.

The father-son duo then travelled to Lisbon, and onward to Rome, where Faria Jr. was ordained a priest and the father-son duo did their doctorates in theology. On their return to Lisbon, the father was left harbouring nativist ideas; the son, seeking a safe harbour, proceeded to France, in 1788.

That’s how the name ‘Abbé Faria’ makes sense. The French word for ‘priest’ is still in vogue in the English-speaking w orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

In 1988, as I arrived in France, Faria’s poignant story raced through my mind like a film. It was exactly two centuries since the only Goan who participated in the Revolution had stepped into Paris. Alas, I found no trace of his addresses in that magnificent global city. So I was hopeful about seeing the Abbé next in the luminous port city of Marseilles. My joy knew no bounds when I finally sighted a street named after him.

There I was quizzing a few pedestrians on that sleepy thoroughfare. When the very first speaker confessed his ignorance, I was crestf allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’

allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’ s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

My third and final encounter was most memorable. When I fired my standard question – ‘Who is this Abbé Faria?’ – the man playfully shot back at me, saying, ‘He was an Indian – like you!’ And with a smile playing on his lips, he vanished into thin air, while I was stuck in a hypnotic state!

Back in Goa, my interest in Faria redoubled. One fine afternoon, very significantly, the fourth of July, my fiancée came along to see my friend Abade Faria in Colvale. Just locating his family estate in that northernmost village of Bardez took us longer than getting there all the way from Panjim. It felt as though we were searching for something in pitch darkness, no flashlights in hand, when really it was broad daylight… What an exploration indeed!

Renowned historian J. N. da Fonseca, who purchased the Faria estate in the nineteenth century, built a house there, possibly on the ruins of the hypnotiser’s family house. Only the private chapel was spared.

When I was working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m

working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

So, you see, it was great getting to know Abade Faria – my civic duty, to say the least. You too can trail him now. Begin today, on his 200th death anniversary.

(Herald Café, 20 September 2019, p. 1)

https://www.heraldgoa.in/Cafe/WHEN-I-MET-ABADE-FARIA%E2%80%A6/151383

Sonia - The Fado's New Fate

Sonia Shirsat is the Fado’s Lady Fate in Goa. On Valentine’s Day she swore her love for Portugal’s iconic melody. That the song has come to stay became obvious from the near-full Dinanath Mangueshkar auditorium that lapped up every bit of Mundo Fado II, Sonia’s first solo show on home turf.

Sonia’s voice is extremely well suited to the fado. Her talent first became evident at the ‘Vem Cantar’ contest (2002), through her superb rendering of Madre Deus’ ‘O Pastor’. Before long, ‘Barco Negro’’ sung by her also became a people’s favourite. And this time, a bright new ship – ‘M. V. Mundo Fado’, if you like! – dropped anchor in Panjim, from where it will again sail the Seven Seas.

Impressive is the line-up of fado greats that Sonia has performed with over the years. But more fulfilling must have been her own first solo concert, Mundo Fado, held in 2008, at Museu do Oriente, close to Alcântara docks, by the Tagus. She sang to a packed house, with guest artistes including Mestre António Chaínho, Manuel Leão, and Casa de Goa’s musical troupe, Ekvat!

Notice the poetry of that fabulous setting: the Orient, harking back to Goa; the proverbial waterfront, where the Fado originated amidst a sailor community; and the Tagus, from where all those intrepid ships once sailed “o’er seas hitherto not navigated… to seek out new parts of the world”….

So it was at Alcântara (‘the bridge’, in Arabic) that Sonia crafted her musical bridge with the fado world. Climbing onto the international stage is no mean task, especially for one not fully born into the genre. Sonia chose to cultivate it, chaperoned by her Lusophile mother Maria Alice Pinho, who belongs to a Goan generation raised on Portuguese music.

Mundo Fado II started off with an evocative instrumental medley by Sonia’s main accompanists, Flávio Teixeira Cardoso (Portuguese Guitar) and Pedro Miguel Soares Marreiros (Spanish Guitar) from Portugal. While they were at it, in walked Sonia draped in a designer gown and shawl. The backdrop was a quiet, understated, white with colour focus lights. Her first song was ‘Cansaço’ (‘Weariness’)… but needless to say both audience and artiste were zestful until the end!

There was a happy mix of familiar and not-so-familiar numbers. ‘Alfama’ (a tribute to Hotel Cidade de Goa’s restaurant of the same name where she is the lead artiste at the monthly ‘Noite de Fado’) was followed by ‘Amor de Mel’, Fado das Horas’, ‘Tive um Coração’, ‘Meu Amor Marinheiro’ and ‘Zanguei-me com o meu Amor’, among others.

Sonia’s show was marked by measured stylistic innovation. It featured the tabla (Mayuresh Dattaram Vasta), the flute (Marwino António da Costa) and the dhol (Santosh Sawant). And in a style all her own, the vocalist had none of that over-the-top emotionality of the Portuguese fadistas, nor did the tempo quicken as the show progressed; but she sang with passion, offering personal and historical snippets in her announcements.

Sonia infused the fado with new blood, giving the genre a fresh lease of life, and perhaps scope for another to emerge (in a Goan tradition of give and take, which people of good will must endorse). ‘Rua do Capelão’, a ‘modern fado Severa’, with flute and guitars, was a tribute to Maria Severa, 19th century Portugal’s best-known fadista. The popular ‘Cartas de Amor’ was backed by flute, tabla and Spanish guitar; and ‘Ave Maria Fadista’ by tabla and the guitars. It was most fascinating to see the Indian instrumentalists gel with their Portuguese counterparts in ‘Barco Negro’. The latter also took to ‘Doreachea Lharari’ and ‘Adeus Korcho Vellu Pavlo’ as fish to water.

Sonia hailed the mandó as ‘Goa’s fado’! And curiously, hiding behind the Konkani title of our best-known farewell song were Portuguese lyrics – the labour of love of a suave Goa enthusiast Manuel Bobone. The ensuing musical dialogue symbolised a confluence of the past and the future; and its melody is an apt signature tune for Sonia’s Luso-Goan musical experiment.

Mundo Fado II unwittingly commemorated the centenary of the modern fado, first recorded in 1910. And, putting behind its nearly five-decade long hiatus in Goa, Sonia gave a clarion call to young fado singers Danika da Silva Pereira, Manuela Lobo and Efigénia de Santana Miranda to rise to the occasion. She also expressed her camaraderie by inviting guest artistes Carlos Manuel Meneses and Allan Abreu (both Spanish Guitar), Daryl Coelho (Mandolin) and Franz Schubert Cotta (Portuguese Guitar) to be on stage with her. And early in the show, she recalled the musical moments shared with Orlando de Noronha and Dinesh K., both of whom couldn’t make it that day….

That’s ‘Team Sonia’ for you, poised to carve out a brilliant new fate for the Fado in Goa!

(Herald, Goa’s Heartbeat, 23 Mar 2011)