Paris perece...

Não podemos imaginar escassez neste mundo moderno de abundância. Muitas vezes, as gerações mais novas admiram a forma como os seus antepassados viveram com recursos limitados e ainda assim chegam a recordar os velhos tempos com ternura. É que eles viviam com fé ou, pelo menos, não ofendiam Deus. Seria errado infligir dor ao Eterno Provedor. Enquanto Ele dá alegria aos que nele creem, os que acreditam em si próprios e se divertem noite e dia acabam por não ver a luz ao fundo do túnel.

As leituras de hoje convidam-nos a confiar muito especialmente na Divina Providência, independentemente das circunstâncias. A Primeira Leitura (2 Reis 4: 42-44) mostra-nos como Eliseu, com apenas vinte pães de cevada, alimentou cem esfomeados. Era a promessa do Senhor, cumprida depois de o profeta lhe ter manifestado a sua total devoção. E o milagre simboliza o facto de nada ser impossível a Deus: Ele conhece e satisfaz todas as nossas necessidades e, sobretudo, as espirituais, dos que anseiam pela Palavra de Deus.

Embora sempre a leitura do Antigo Testamento se encontre coordenada tematicamente com o texto do Evangelho, neste domingo essa ligação fica claríssima. Ambas as leituras falam da multiplicação dos pães. Do Antigo Testamento vemos como Deus dá pão aos israelitas que passam fome no deserto (Ex 16: 4) e como Elias cria uma fonte inesgotável de farinha e de azeite para sobreviver à fome (Reis 17: 15-16); mas nem um nem outro desses exemplos se assemelha à história do Evangelho de hoje (Jo 6: 1-15).

Relatos evangélicos

Há seis relatos evangélicos sobre a multiplicação dos pães. Jesus alimentou duas vezes o povo – de uma vez, 5.000 comeram de cinco pães e dois peixes, e sobraram doze cestos daqueles; e noutra ocasião, 4.000, com sete pães e alguns peixes, e sobraram cinco cestos. Aquele é o único milagre (para além da Ressurreição) que se encontra registado nos quatro Evangelhos; e apenas Mateus e Marcos, sob pena de repetição, registaram ainda o segundo.

Este milagre realça a sensatez de uma abordagem sobrenatural, mesmo quando se trata das nossas necessidades materiais. É da essência confiar no Senhor, que disse: “Não vos preocupeis, dizendo: ‘Que comeremos, que beberemos, ou que vestiremos? Os pagãos, esses sim, afadigam-se com tais coisas; porém, o vosso Pai celeste bem sabe que tendes necessidade de tudo isso. Procurai primeiro o Reino de Deus e a Sua justiça, e tudo o mais se vos dará por acréscimo. Não vos preocupeis, portanto, com o dia de amanhã, pois o dia de amanhã já terá as suas preocupações. Basta a cada dia o seu problema. (Mt 6: 31-34).

É claro que todos os nossos problemas terminam à Mesa da derradeira refeição que Jesus nos ofereceu: a Sagrada Eucaristia. Isto acontece em cada Sacrifício da Missa. A multiplicação dos pães prefigurava o exemplo supremo de amor de Nosso Divino Senhor e Mestre, instituído na Última Ceia. Por isso, foi muito doloroso ver tudo isso parodiado na cerimónia de abertura dos Jogos Olímpicos em Paris na última sexta-feira.

Pouco importa que o desfile tenha sido fora do contexto do desporto; e seria um eufemismo dizer que ele foi de mau gosto. A vaidade em desfile traiu a memória de Carlos Magno e foi uma afronta à religião que moldou a França. O rei dos Francos, que se esforçou pela união dos povos cristãos, foi considerado o “Pai da Europa”, e o seu país chamado a “filha mais velha da Igreja Católica”. Assim, o que se passou em França no dia da semana em que Cristo morreu é nada mais nada menos do que pecado nacional que clama aos céus por vingança.

Paris ou perecimento?

A unidade da Europa cristã, tão desejada por Carlos Magno, foi uma reprodução fiel do que São Paulo, séculos antes, havia querido em relação à Igreja. Na Segunda Leitura (Ef 4: 1-6), o Apóstolo dos Gentios implora ao seu povo que leve uma vida digna da sua vocação: “Existe uma só esperança na vida a que fostes chamados. Há um único Senhor, uma única fé, um único baptismo. Há um só Deus e Pai de todos, que está acima de todos, actua em todos e em todos se encontra”. Sim, em nós e em França. Infelizmente, a nossa reacção foi pobre, trágica, e as consequências não podem ser diferentes; é uma questão de justiça sobrenatural....

No entanto, quaisquer que sejam os problemas que enfrentamos, individualmente, como nação ou como civilização, eles nunca são demasiado grandes para Deus. Assim, quando multiplicamos os problemas, Deus multiplica as soluções; quando multiplicamos as maldições, Ele multiplica os julgamentos; e ainda, quando multiplicamos as orações, Deus multiplica as bênçãos. Igualmente oportuno é notar o lema de Carlos Magno: In Scelus Exsurgo Sceleris Discrimina Purgo (“Luto contra a agressão e castigo o agressor”).

A paródia parisiense é a Revolução Francesa em modo loop. A revolução continua, destinada contra a Igreja Católica. Todas a reconhecem, menos os católicos! Somos talvez os únicos que gozam livremente com a própria Mãe, a Igreja. Quem se atreveria a tentar estas palhaçadas contra outras religiões? Devemos perdoar mesmo quando a nossa Mãe está a ser atacada? Já nada é sagrado?

Será que Roma e a Igreja em França e em todo o mundo vão então condenar formalmente esta situação? E tu e eu? Será que vamos aceitar estupidamente, mais uma vez, que o inimigo tem razão e que só nos resta dizer “Touché”?

Banner: https://rb.gy/r69d67

The Two Abbés

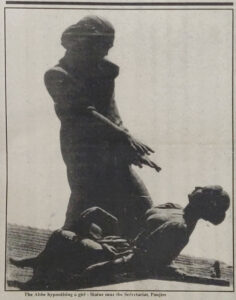

Who in Goa hasn’t seen that striking bronze figure of a tall man in a flowing robe, with a lady tumbling down at his feet? Sculpted by Ramachondra Panduronga Kamat and erected next to the Adil Shah Palace, the statue is now in its seventy-fifth year. It was a tardy tribute to a nineteenth-century Goan celebrity – Abade Faria – considered the ‘father of modern hypnotism’.

For every passer-by that admires that lofty monument, there are thousands the world over who would be reminded of a literary character of the same name: Abbé Faria from Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte-Cristo. This adventure novel was published a century before that statue was put up in Panjim.

Are the Abade and the Abbé one and the same person? Faria is a surname; abade and abbé mean ‘abbot’ in Portuguese and French, respectively. The historical Faria only served as a literary inspiration for the celebrated French writer. Some parallels are obvious between the two figures but not all of them do justice to the flesh and blood Faria.

The real Faria was born José Custódio de Faria, in Goa, then Portuguese India. After eight years of priestly studies and a doctorate in Rome, he lived in Lisbon for the same number of years. Finally, he settled down in Paris, where he spent over thirty years, with a year or so in Marseilles and Nimes. In France he was referred to as Abbé Faria.

Dumas’ learned Abbé is a linguist, philosopher, and a strong-willed man. Our Abbé was proficient in philosophy, theology, history, and he intuitively discovered hypnotism; he knew Konkani, Portuguese, Latin and French; and was a resolute man. The physical attributes of the two are similar, except for their height.

The novel is set in the bay of Marseilles, where the fictional Abbé is imprisoned; the real Abbé worked in that port town as a professor of philosophy, in 1811. The former is nicknamed ‘Mad Monk’ by the prison staff; quite intriguingly, our Abbé too was derided by doctors, writers and fellow pastors for his ideas on hypnotism, in Paris (1813-19). Similarly, the Abbé’s description of lodging and boarding in jail could well be a mirror image of the real Faria’s living conditions at the Orties convent. Dumas’ inspector of prisons would be the equivalent of an actor, Potier, who lampooned our Abbé in Jules Verne’s fateful play, Magnétismomanie.

Coming now to Abbé Faria’s tunnelling for three long years: it could be interpreted as the real Abbé’s quest for ideas and materials in support of his theory of sommeil lucide (lucid sleep). When they died of fulminating apoplexy, in their sixties, both characters had their books still unpublished. The real Faria’s book De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man) came out posthumously; the remaining three volumes were untraceable, much like the jailed Abbé’s book that was never found.

While Dumas’ Abbé is an Italian, born in Rome; the Goan Abbé was born in the ‘Rome of the East’. The hero, Dantès, once journeyed to India, whereas José travelled from India to Europe, and never went back to his homeland. Interestingly, the fathers of both have important roles in their sons’ lives. Could Dumas have known that José’s father in Lisbon was under house arrest for his nativist ideas, and that many of the conspirators of 1787 in Goa met with a fate worse than death? Apparently, José’s father and Dumas himself were both republicans at heart.

Finally, the treasure that the Abbé highlights in the novel could be a pointer to the treasure that the historical Abbé Faria endowed us with, in the form of hypnotism: this has long been an invaluable aid to the physical and mental well being of humankind.

It is sad that Faria fans find it hard to separate fact from fiction: shrouded as he is in deep mystery, the real Faria comes out largely disfigured. But given that historians and medicos took no steps to fix that shortcoming, how can one fault Dumas for taking artistic licence? After all, the man who died, disdained and forgotten, on 20 September 1819, was kept alive in the pages of The Count of Monte-Cristo. It now behoves us to put the historical Faria on a pedestal much higher than the one on which he is placed in Panjim’s main square.

When I met Abade Faria...

I lived next door to Abade Faria for thirty years. As a child, I remember asking my father what that name meant. Keen on passing on informatio n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

n about our land and our people, Papa said he was a priest who had the distinction of being the discoverer of hypnotism. As for me, I didn’t quite like to see Faria in that strange pose. It was terrifying to see that lady tumbling down before his very eyes; it even seemed like he had knocked her down. But then, I wouldn’t speak ill of my neighbour, or ask odd questions…

Abade Faria is that very striking statue in the heart of Panjim. I couldn’t have met the man himself: José Custódio de Faria was born in 1756, at his mother’s house in Candolim. His father was from a less known village, Colvale. As I came of age, I learnt that he was the son of a priest and a nun… Hold on! They were ‘normal’ people, Caetano Vitorino de Faria and Rosa Maria de Souza, who got married, had a child, and then broke up. The father took holy orders at the then Chorão seminary while the mother joined St Monica, Asia’s largest nunnery, at Old Goa.

The father-son duo then travelled to Lisbon, and onward to Rome, where Faria Jr. was ordained a priest and the father-son duo did their doctorates in theology. On their return to Lisbon, the father was left harbouring nativist ideas; the son, seeking a safe harbour, proceeded to France, in 1788.

That’s how the name ‘Abbé Faria’ makes sense. The French word for ‘priest’ is still in vogue in the English-speaking w orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

orld. Faria spent the last three decades of his life in Paris, Marseilles and Nîmes. In the midst of the Revolution, he was attracted to magnetism. ‘Magnetism’ was the older word for hypnotism, which the Abbé reinterpreted as “sommeil lucide” (lucid sleep) in his magnum opus De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man), published posthumously.

In 1988, as I arrived in France, Faria’s poignant story raced through my mind like a film. It was exactly two centuries since the only Goan who participated in the Revolution had stepped into Paris. Alas, I found no trace of his addresses in that magnificent global city. So I was hopeful about seeing the Abbé next in the luminous port city of Marseilles. My joy knew no bounds when I finally sighted a street named after him.

There I was quizzing a few pedestrians on that sleepy thoroughfare. When the very first speaker confessed his ignorance, I was crestf allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’

allen. But I bounced back on hearing my next interlocutor wax eloquent on the Abbé as a hypnotiser figuring in Chateaubriand’ s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

s memoirs and in Alexandre Dumas’ adventure novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

My third and final encounter was most memorable. When I fired my standard question – ‘Who is this Abbé Faria?’ – the man playfully shot back at me, saying, ‘He was an Indian – like you!’ And with a smile playing on his lips, he vanished into thin air, while I was stuck in a hypnotic state!

Back in Goa, my interest in Faria redoubled. One fine afternoon, very significantly, the fourth of July, my fiancée came along to see my friend Abade Faria in Colvale. Just locating his family estate in that northernmost village of Bardez took us longer than getting there all the way from Panjim. It felt as though we were searching for something in pitch darkness, no flashlights in hand, when really it was broad daylight… What an exploration indeed!

Renowned historian J. N. da Fonseca, who purchased the Faria estate in the nineteenth century, built a house there, possibly on the ruins of the hypnotiser’s family house. Only the private chapel was spared.

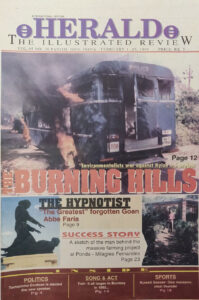

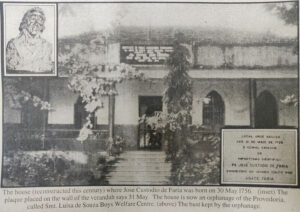

When I was working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m

working on an article for the fortnightly Herald Illustrated Review, way back in 1995, I also visited the Souza house in Candolim, now an orphanage. It’s still the same today. Not a pretty sight, but there is at least a plaque m arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

arking the birth of Goa’s most eminent, self-trained scientist who left his footprints on the sands of time.

So, you see, it was great getting to know Abade Faria – my civic duty, to say the least. You too can trail him now. Begin today, on his 200th death anniversary.

(Herald Café, 20 September 2019, p. 1)

https://www.heraldgoa.in/Cafe/WHEN-I-MET-ABADE-FARIA%E2%80%A6/151383

The Hypnotist in Holy Orders

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

Precious little remains till date in the memory of the average Goan. There is a statue of him in the capital city and a street takes his name in Margão. He has been forgotten in his native village of Candolim; only a primary school is named after him there and in some other villages too. He is almost unknown where he worked and lived – Lisbon, Paris and Marseilles. Only an obscure street is named after him in Marseilles.

People may not be apt to remember somebody who lived two centuries ago and with a mysterious sounding name such as Abbé Faria. But what if he has some original scientific contribution to his credit? Never mind that he was a theorist of hypnotism by suggestion, which has since become a vital aid to psychiatry, psychoanalysis and surgery. Very often his name is omitted when the subject comes to the fore. Not even does the Encyclopaedia Britannica refer to him as they do Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) and James Braid (1795-1860), who have only usurped his pride of place.

Such has been the fate of José Custódio de Faria (1756-1819), a priest and doctor of theology, who without any medical training did perceive and lend respectability to the true nature of what he called ‘sommeil lucide’ (lucid sleep). It was an intuition characteristic of a true genius. And for this original contribution to the field of science he is regarded at home as the greatest Goan that ever lived.

Early Life

José Custódio de Faria was born on 31 May 1756, to Caetano Vitorino de Faria of Colvale and Rosa Maria de Souza of Candolim. His father was a seminarian and had already received minor orders when he met and married Rosa, the only daughter of a rich landlord of Candolim. He was clever and she was rich, but the combination did not work out that well. Even their son born two years after their marriage, could not prolong their mutual love. Around the year 1764, they got a canonical decree of separation in 1764. He took holy orders and she joined the Santa Monica convent in the  old city of Goa.

old city of Goa.

No bonds linked them ever since. The father and the son stayed a few years at their friends in Candolim – the Pintos of the Conspiracy fame – and at Colvale too. On 21 February 1771, four years after being ordained a priest, Caetano Vitorino left for Lisbon, en route for Rome, to continue his priestly studies. He had similar intentions for his son. Their social circle in Goa and particularly a letter of recommendation they carried for the nuncio in Lisbon, Mgr. Inocencio Conti, won them access to the royal court. Moreover, the reigning monarch, Dom José I, and his prime minister, the Marquis of Pombal, were favourably disposed towards the Goans, whom they strongly recommended for civil, military and ecclesiastical positions at home.

Student in Rome

Thus José Custódio was awarded a scholarship to study in Rome. The father returned to Lisbon in 1777 on attaining a doctorate to further his objective of objective of being appointed the bishop of Goa. His great disappointment and frustration on this count determined much of what followed in his life and his son’s too.

José Custódio stayed on and was ordained on 12 March 1780. At 24 he completed his doctoral thesis titled Theologicae Propositiones: De Existentia Dei, Deo Uno et Divina Revelatione (Theological Propositions on the Existence of God, One God and Divine Revelation) and joined his father in Lisbon.

The duo were good friends but a different purpose animated them. Caetano Vitorino, the more political minded and diplomatic of the two, was fully immersed in matters Goan. He was a sort of self-appointed protector of and influential reference for the Goan community. The Court had been impressed by the fact that, though immensely influential at the highest levels of the kingdom’s administration, he had never asked favours for himself, though it was known that his personal finances were far from bright. But then, intelligence reports began to pin him down as the mastermind and coordinator in Lisbon of a political revolt at home in 1787. As soon as news of this reached Lisbon, they hunted for the duo and their good friends, clerics and laymen.

Meanwhile, all except Fr. Caetano Vitorino had fled to Paris, reportedly to meet and discuss with their envoys of Tipu Sultan, who proposed to be on the French side in their ascendancy against the British in India, but nothing was confirmed in this respect. Others believe that simpler reasons motivated Fr. José Custódio’s sudden departure – that he was attracted by the intellectual climate of France. His father did, however, stay back, still persevering in his designs and probably even overestimating his influence with the high officialdom. He was then put under house arrest in the Carmelite convent where he gave his priestly assistance, and probably died in 1799.

In Paris

Nothing is known of Fr. José Custódio’s activities in the French capital except that he was accused, in 1792, of being a gambler and frequenter of the Palais-Royale. He was acquitted, or at least no action was taken against him by the police. Three years later, on 5 October 1795, he led a battalion of revolutionaries against the National Convention. This political stand made him popular with the supporters of the Directoire and won him the friendship of the Marquis de Chastenet de Puységur.

The latter relationship was decisive. The Marquis had been a disciple of Mesmer whose quackish furrows into ‘animal magnetism’ and tall claims of cures had initially won him the acclaim of high Parisian society. But, in 1785, his exit was shameful. The Marquis, on the other hand, was an honest, well-meaning and cultured person, who took over from where Mesmer had left. Dr Egas Moniz, the Portuguese Nobel Prize Winner and biographer of Fr. José Custódio de Faria, speculates that he acquired knowledge of magnetism in Paris after he struck up an acquaintance with the Marquis.

The first news of Fr. Faria’s activity as a magnetizer is of the year 1802, in the memoirs of Chateaubriand (published in 1843), who referred to his experiments in derogatory terms. He had dined with Fr. Faria at the house of the Marchionesse of Custine. Here, Fr. Faria reportedly declared that he could kill a canary by magnetizing it. However, when the magnetizer was put to the test, he failed, which led Chateaubriand to conclude: ‘O Christian, my presence itself will be enough to make the tripod ineffective!’ Chateaubriand was a devout Catholic. He had strong reservations against magnetism – because of the Church’s attitude of suspicion towards it. But what is more is that Fr. José Custódio de Faria was a Catholic, no less!

Fr. José Custódio continued his research into the subject up to the year 1811, when he was appointed professor of Philosophy at the Academy of Marseilles. The Imperial Almanac of 1811 records that he lived there a year and was elected member of a medical society. Since he had no medical qualifications, the membership can only be attributed to his skills as a magnetizer. But for some mysterious reason, he was transferred, in fact, demoted, to the post of auxiliary professor at the Academy of Nimes. He felt slighted and frustrated and, unaccustomed as he was to life in a small city like Nimes, he returned to Paris, in 1813, in search of greener pastures. Unattached to any institution, he initiated his course in magnetism on 11 August 1813, 49, Rue de Clichy.

Sessions

The sessions were held every Thursday, on an admission fee of five francs only. He began with a lecture in halting French. The audience, which consisted largely of women, paid scant attention to this part of the session; their eyes were set on what was to follow – his experiments to substantiate his theory.

Contrary to the claims made by Mesmer, the he could control the body fluids of his patients and rectify their course through special methods invented by him, Fr. José Custódio very humbly put forth that not all individuals could be hypnotised, and that the degree of response to his hypnotic powers necessarily varied from person to person. He was the first to establish that hypnotism was a science of suggestion.

Fr. Faria’s method consisted of a series of well-reasoned and effective actions: he got the patient to sit comfortably and, through concentration, to relax, imagining that they were going to sleep. When the patient was ‘tranquil’, he gave the command, ‘Sleep!’ and, if necessary, repeated it, with a certain degree of urgency, three or four times. If he failed, he would either sportingly give up or try other methods.

The sessions became the rage of the town. There were detractors, critics and skeptics, no doubt. Once, a journalist attended his session and then unjustly criticised and ridiculed the priest in the press. At another session, a leading stage actor, Potier, offered himself for his experiments. He feigned to be in a trance and suddenly rose to say, ‘Ah, Abbé! If you magnetize others as well as you magnetized me, you don’t seem to be doing much.’

Fr. José Custódio put up very well with all such betrayals. He also withstood quite stoically criticism from the clergy and Rome, who then viewed his experiments with suspicion always on the look-out for diabolical influences therein. But the priest always expressed respect for the Church and a firm desire to stay within the Catholic fold. ‘Un esprit supérieur,’ as his disciple Gen. Noizet said of him, he wished to convince the Church that his experiments were fully within the natural realm and that there was no magic or witchcraft involved.

Thus, Fr. Faria took everything in its stride. Only once did he break down, when at Potier’s request the playwright Jules Verne put up a play, on 5 September 1816, the Variétés, titled La Magnétismomanie, ridiculing the Goan priest.

Sad end

The time was now ripe for Fr. Faria to stop his activities. He retired soon thereafter, rendering priestly services in exchange for boarding and lodging.

During the last years of his life, he decided to organize his material in book form. It was an ambitious project in four volumes, of which only the first one is known to have appeared. It is his magnum opus is titled De la cause du sommeil lucide ou Étude de la nature de l’homme (On the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study on the Nature of Man). In it he referred to the shameful play:

‘With regard to Magnétismomanie, I cannot ask which laws permit the modern Terence to expose an unknown foreigner to public ridicule. I presume that even the savage would be ashamed to insult his kind, which has nothing in common with actors and the theatre.

‘Far from me the idea to disturb public pleasures: But I might have added to Magnétismomanie a new scene – an extremely pungent one – had my condition not prevented me from doing so, and had my own aversion for such amusements not kept me away from playhouses.’

According to one biographer, by a strange coincidence, the day of his death, also marks the release of his book. His famous words, ‘There are evils that sometimes do good to those who discern their utility,’ might have very well served as his epitaph – if only he had the money for a decent burial. He died at the age of 63, unsung as he was born. A life full of ironies, for born of a rich family he died poor; born of parents who were in love, they separated after his birth; a man with original contributions to posterity, he died with no godfathers to promote his name.

(Herald Illustrated Review, Panjim, Goa. Vol. 95, No. 30, February 1-15 1995. Slightly updated version)