Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

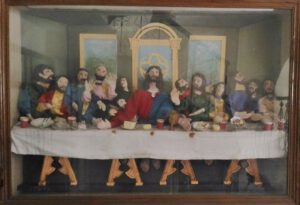

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

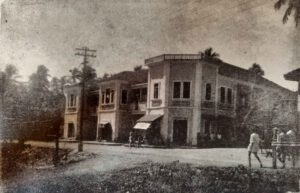

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

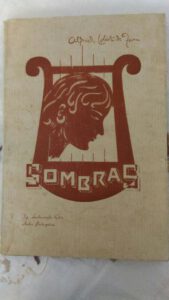

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

Tribute to my Father

Early this month the social media was abuzz, in anticipation of the twenty-twenties; as for me, I was on a solo trip back to nineteen-twenty. As a child, this year had the earmarks of a happy milestone for me, yet it triggered anxiety for the future. My childhood was a shrine of happy pictures, yet the thought of that golden marker fading into the horizon would fill me with sadness. Why? Because while a young me was looking ahead to what would be, my father Fernando was already looking back upon what had been….

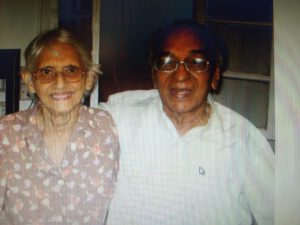

My lone source of anxiety for the future was that I was the eldest child, born in Papa’s forty-fourth year. I knew not how long I would have him: it was a worry I kept to myself so as not to dishearten him. But then, hardly anything disheartened him; he kept pace with his children and even his grandchildren’s progress, and enjoyed the sleep of the just. When he passed on, at 91, he was a grandfather to fifteen. His abiding trust in God was the secret of his longevity – as well as a salutary lesson on the futility of anxiety.

In my naiveté, 1920 still felt charming; as I grew older, I found Papa’s idealism, independence and integrity appealing. I looked up to him, especially because his life hadn’t been easy: the ‘roaring twenties’ of the West had played out quite differently in Portugal and Goa. Following a decade of political turbulence and galloping inflation, the country stabilised and the escudo roared upon the rise of Salazar the economist. Convinced that he was a man with ‘the right intention’, my father held him in esteem for his intellect and honesty – the antithesis of leaders in sham democracies.

After God, it was Goa uppermost in Papa’s mind. The Mass and the Bible alongside spiritual classics were his daily fare. To compensate for arid bureaucratic matters, he put his faith in reading, writing, teaching and music. Even while he took delight in the Romantics Eça, Camilo and Ramalho, he recommended some excellent Goan writers. Until his last breath he lapped up the masters of the Portuguese language, not forgetting two of our very own Goan purists, Costa Álvares and Filinto C. Dias.

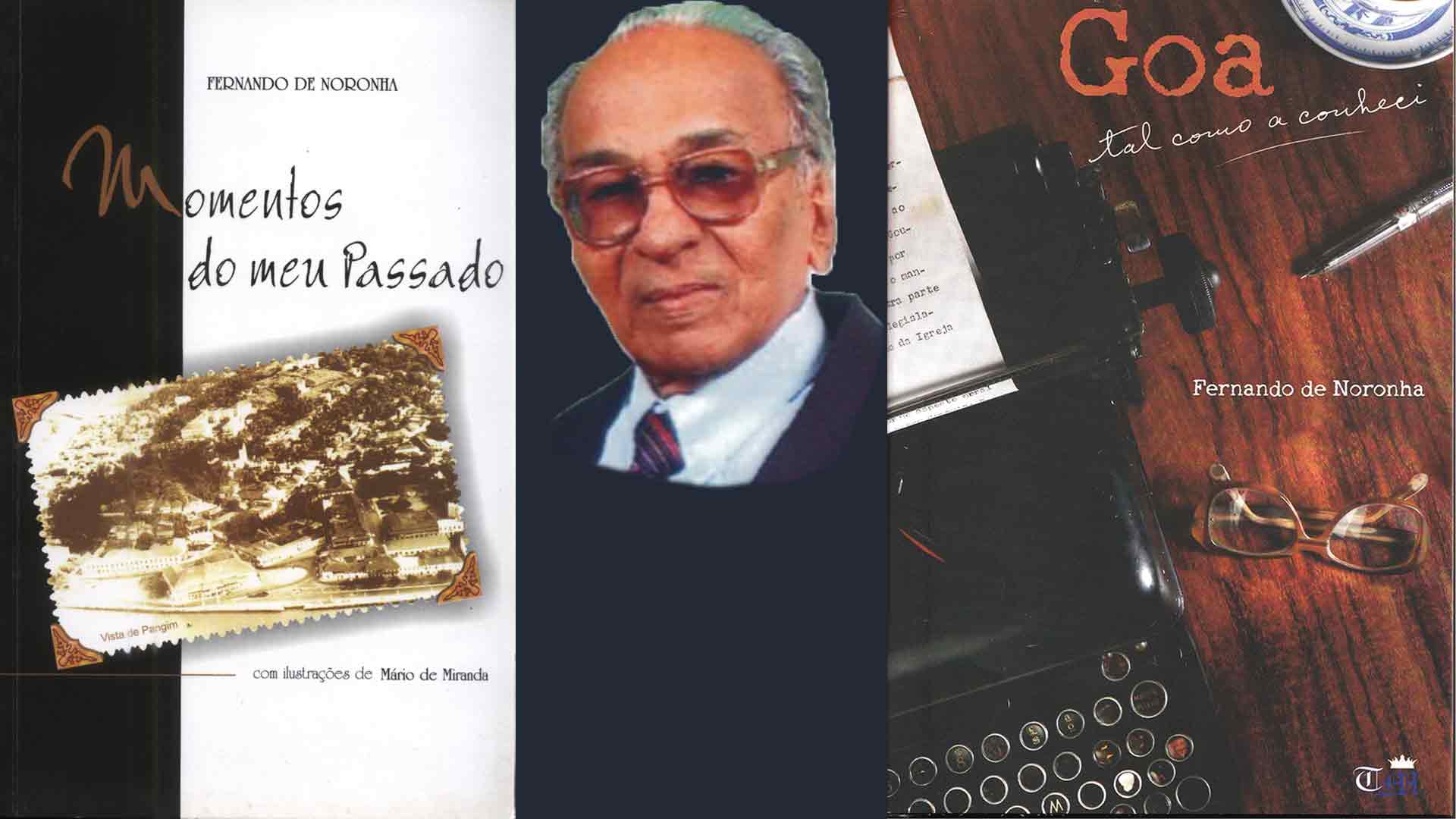

One gets a bird’s eye view of Papa’s outlook from his first book, Momentos do meu Passado (Moments from my Past). Much of it is what he used to recount animatedly at the dinner table or talk over with relatives and friends. He obliged us by writing this slim volume comprising ‘figures, facts and facetiae’: pen sketches of over thirty personalities from the Goan social and political milieu; some little-known facts of contemporary history; and a host of anecdotes dating back to his Lyceum days. In his words, he wished ‘to quench saudades of a not so distant past, when one lived in a happy and carefree manner unique to Goa.’

It took me some time to appreciate Papa’s simple and straightforward nature. And noticing how people would often agree but also end up severing ties with him, I learnt that truth can indeed puzzle, confound, hurt… Papa’s intermittent observations on public affairs are lost in the thicket of Heraldo and A Vida for, whilst a bureaucrat in two key departments during the Portuguese regime, he used pen names of which he kept no record. In 1967, his commitment to ferry people to the booths on the occasion of the Opinion Poll (16 January, his birthday and feast of St Joseph Vaz) fetched him a resounding office memo.

It warms the cockles of our hearts to see that Papa’s second book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), contains the essence of his views on people, events and ideas. Covering as he did twentieth-century Goa’s political and administrative affairs, society, culture, and religion, in a total of eighteen chapters, this offering is a testimony of love for the land and the people. It is also a tribute to the Portuguese language that was so dear to him. After opting to retire from public service, he taught that idiom at a city college and co-founded a weekly, A Voz de Goa. At Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church he prayed in that ‘language of the angels’ and put together a choir at Sunday mass.

Music was high up on his agenda ever since his father purchased a gramophone and a maternal uncle and self-taught violin virtuoso played along. An attractive feature of Papa’s day was his whistling and playing of the harmonica, providing the household with a kind of crash course in classical and semi-classical music. The mandó moved him very especially (he ensured that it featured at his children’s wedding parties) and so did two popular Konkani films of his time which, he said, ‘foster Goan patriotic feelings’. The Goan reality, however, was a far cry from what he had envisioned, so I can say with Wodehouse that ‘if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.’

No tribute to our father would be complete without a reference to our dearest mother Judite da Veiga, who was the love of his life, the reason of his being. On his death bed I heard him thank her for half a century of togetherness. She, their five boys and families, was all that he ever wanted. We have lost him in body, not in spirit. He has become greater in death, our strength and consolation, our conviction that there can be no anxiety for the future….

Herald, 19.01.2020, published an abridged version

For this full version see Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), March-April 2020

https://issuu.com/casadegoa/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n3_-_mar-abr_2

Aquela doce palavra ‘Fátima’…

Era eu ainda menino quando ouvi da boca da Avó Leonor a história de Nossa Senhora de Fátima. Nessa altura, foi o enredo, ou seja, a descrição pastoral, que deveras me impressionou; e também o facto de a Mãe de Jesus ter pedido a recitação diária do Terço e que os maus se tornassem bons para poderem alcançar o Céu.

De vez em quan do ia lendo umas publicações sobre Fátima que tínhamos na nossa biblioteca em casa – uma delas, Fátima, Altar do Mundo, de João Ameal. Atraía-me esse fantástico subtítulo – “Altar do Mundo” – bem como as lindas fotografias a preto e branco.

do ia lendo umas publicações sobre Fátima que tínhamos na nossa biblioteca em casa – uma delas, Fátima, Altar do Mundo, de João Ameal. Atraía-me esse fantástico subtítulo – “Altar do Mundo” – bem como as lindas fotografias a preto e branco.

Uma outra publicação que costumava folhear era o Souvenir publicado em Goa por ocasião do cinquentenário das Aparições de Fátima (1967). Tinha artigos da autoria de escritores goeses – inclusive hindus – escritos em português, inglês e concani.

Nesse opúsculo vi pela primeira vez uma foto memorável de que falava meu pai: a Imagem da Virgem Peregrina a atravessar o rio Mandovi, a caminho da Velha Cidade, no dorso dum gasolina que se apresentava em forma dum grande cisne branco fabricado por artistas goeses. E, desembarcando junto ao Arco dos Vice-reis, essa imagem seguiu em magno cortejo até o local onde iriam ser rezadas, simultaneamente, 153 missas, a representar as Ave-Marias do Rosário! Que imponente cena! Nessa visita que se realizou de 29 de Novembro a 12 de Dezembro de 1949 a Imagem percorreu o território de Goa.

Daí a vinte e cinco anos, ou seja, em 1974, foi anunciada uma outra visita da Imagem. Desta vez, houve grande polémica na imprensa local. Não me lembro qual foi o argumento principal; sei só que se tratava de um debate entre duas gerações de clérigos goeses. Porém, quando chegou a Imagem houve grande concorrência dos fiéis. Com os meus 9 anos de idade fiquei com esta dúvida: como é que podia haver duas opiniões sobre a visita da Mãe de Jesus?!

9 anos de idade fiquei com esta dúvida: como é que podia haver duas opiniões sobre a visita da Mãe de Jesus?!

Entretanto, constituíam já uma tradição consagrada as chamadas procissões de velas, que se realizavam na capital, em Maio e Outubro. Era entoado um e outro cântico em português. Embora parecesse um simples ritual herdado a Portugal, para mim era esse país era o “povo escolhido” dos tempos modernos (já que o antigo não se portara bem!)

Também meu pai, de saudosa memória, sem nunca se esquecer do sentido mais amplo da mensagem de Fátima, parecia frisar o lado português do grande acontecimento que se tinha dado em Fátima, exprimia esse sentir no seu poema “Portugal e Fátima”, que veio publicado n’O Alcoa, de Alcobaça:

Portugal e Fátima Primeira Grande Guerra… Só sangueira, Luto e desolação por toda a Terra!… Angustiada, aparece, pois, na Serra A nossa Virgem Mãe numa azinheira (Cova da Iria); e diz com emoção que vão cessar as hostilidades (é a bonança a seguir a tempestades). Anima o mundo à sua reconstrução. E a Portugal diz:- Eis que te darei Dois jovens que guiarão nessa peleja: Um, que traz veste da cor de cereja; E o outro, de quem muito justamente d’rei: Tem muito sal na fala e afasta o azar.– E assim foi, pois: seguira-se uma era De real prosperidade e paz sincera, Por cerca de meio séc’lo, sem armar… Tal como não há rosas sem espinhos, Não podem faltar cravos nem cravinhos Que perturbem a vida nacional Neste sempre querido Portugal! Mas, haja o que houver, disse a Senhora de Fátima que é sua protectora nata:- “Meu Coração, pois, triunfará”. E, quem acreditar não poderá?

Em 1987, tive o ensejo de visitar Portugal. Fui a Fátima, onde vi peregrinos de joelhos; e uns a cantar e outros a chorar… Emocionante! Impressionou-me bem o recinto do Santuário e a vasta praça pública mas fiquei triste por ver uma intensa actividade comercial ao redor!

Entretanto, fui reflectindo sobre o facto de Fátima não ser um mero sítio ou história: os três pastorinhos eram afinal personagens ímpares no palco internacional e arautos da mensagem divina que merecia bem ser escutada pelo Planeta Terra.

Depois que voltei a Goa, em 1988, estive em contacto com a Sociedade Brasileira de Defesa da Tradição, Família e Propriedade, que tinha acabado de publicar o livro intitulado As Aparições e a Mensagem de Fátima nos manuscritos da Irmã Lúcia, de autoria de António Augusto Borelli Machado. Este livro teve depois uma edição inglesa, feita em  Goa. Eram os anos do desmoronamento do Império Soviético e outros acontecimentos apocalípticos cuja explicação completa se encontrava na mensagem de Fátima.

Goa. Eram os anos do desmoronamento do Império Soviético e outros acontecimentos apocalípticos cuja explicação completa se encontrava na mensagem de Fátima.

Tornei-me ainda mais devoto da Senhora de Fátima. Mas enquanto eu fitava a sua dimensão universal, Nossa Senhora olhava, com carinho maternal, para a minha vida pessoal: ajustar-me-ia com a Isabel, nascida em 13 de Maio, e levando por isso os nomes Maria e Fátima!

Cinco anos depois, casámos nesse dia. No fim da missa do casamento a Isabel fez (e eu renovei) a Consagração a Nossa Senhora segundo o método de S. Luís Maria Grignion de Montfort!

Uma e outra pessoa, católica mas também supersticiosa, nos tinha recomendado não casar no dia 13, sexta-feira. Mas pusemo-nos, a Isabel e eu, incondicionalmente a favor dessa data.

Um ano e meio depois sucedeu-nos algo que essas pessoas devem ter tomado como plena justificação dos seus palpites. Nascia-nos um menino – Fernando – que, pouco depois, começou a ter problemas bastantes graves! Pensámos, porém, que Deus podia mandar uma prova dessas a qualquer pessoa; com que direito poderíamos ser uma excepção? O importante era Deus estar connosco, como realmente esteve, e continua a estar!

No hospital, onde passámos os primeiros três meses da vida do Fernando, cheguei a ler, com grande consolação e deleite espiritual, o livro Fatima, de William Thomas Walsh. Foi um dos poucos livros que pude ler durante o período da crise por que passámos, a Isabel e eu, junto com a família inteira.

Tomámos tudo isso como uma prova da nossa fé; e tínhamos já recebido a resposta a todas as dúvidas suscitadas no interim: era a Senhora de Fátima que nos vinha ajudar a encarar de forma sobrenatural a vida, esta nossa peregrinação na terra.

Fernando não se curou completamente mas sucedeu algo que a medicina não achava possível... Está estável, com uma alegria de viver, e é devoto de Nossa Senhora!

Uns anos depois nasceu-nos o Emmanuel, que leva o nome do Esposo de Maria Santíssima: José! E quando nasceu a Vera, uns dias após a morte da Vidente Lúcia, foi ela baptizada também com esse nome de luz.

Eis algumas facetas da nossa relação com a Mãe Celeste… E eis porque ainda nos fala ao coração aquela doce palavra Fátima.

(Em conversa com Cristina Arouca, em 2012)

(Em conversa com Cristina Arouca, em 2012)

Ver:

Fátima no Mundo, de Manuel Arouca e Cristina Arouca Editora Ofício do Livro, 2016) https://www.amazon.com/F%C3%A1tima-Mundo-Portuguese-Manuel-Arouca/dp/9897414320) Fátima e o Mundo, documentário, Ep. 611, Dezembro de 2016: Fátima e a Ásia e a Oceânia. https://www.rtp.pt/play/p2909/e263645/fatima-e-o-mundo

Remembering Leonor: Editor Extraordinaire

To the dead it probably matters little whether or not they are remembered: having done their bit on earth they now belong to Eternity, where worldly honour and glory are of no consequence. But paying them homage is a cardinal civic virtue – an expression of gratitude for the valuable services rendered by them to the community, which also helps to imbibe sterling values that might well be scarce in a new day and age.

That is what links us to Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes on her birth centenary. Born on 24th May 1909 to Miguel de Loyola Furtado of Chinchinim and Maria Julieta de Loyola of Orlim, she was married to Martinho António Fernandes of Colvá. She was a woman of many parts but essentially a matriarch and a grand lady of the Fourth Estate.

Wife and Mother

Leonor – Lolita, in her close circle – was a person ahead of her times. She was a career woman with a difference. When the Panjim-based eveninger Diário da Noite (2nd May 1953) asked about the beginning of her occupation, she said, ‘I don’t remember clearly when I started writing. I know I became a mother at 16 and it must have been after this that I began writing in earnest.’

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

And reflect it did. As Administrator of the Comunidades of Salcete, Martinho Fernandes, a lawyer by training, was dogged by controversy, initially fomented by individuals who eyed his post, while later some of it was fuelled by a heady mix of personal vengeance and political vendetta, thanks to his wife’s plain speaking in the weekly A Índia Portuguesa. The incumbent emerged unscathed, through long and tortuous battles up to the apex court.

It must not have been easy for Leonor to weather those storms while she raised four daughters, managed the household chores and the family estates. But the years rolled by and, interestingly, at 39 years of age, she was already a grandmother! In 1950, when that venerable journal, a family heirloom and historic mouthpiece of the pro-native political party called Partido Indiano, founded by the Loyolas of Orlim, was almost folding up, it was born again with Leonor.

Journalist and Author

It was for the first time that in the whole of the Portuguese speaking world and in the Indian sub-continent as well a woman was at the head of a newspaper. This was only a natural consequence of having her father for a role model: apart from being a brilliant physician and political leader, he had edited A Índia Portuguesa from the year 1912 until his sudden demise in 1918, and his memory remained with Leonor for the rest of her days. She once said, ‘If destiny were not opposed to it, I would have studied medicine. I had a fascination for the medical profession, so as to positively spread the good to all. But I was born for something else – and I am a journalist only. I would have liked to be a physician and journalist.’ (Diário da Noite)

A year after assuming editorship she travelled to Portugal, the only lady in a Goan media delegation comprising Fr Manuel Francisco Lourdes Gomes, Álvaro de Santa Rita Vaz, Amadeu Prazeres da Costa and Luis de Menezes Jr. They had been invited for a month’s stay, to see for themselves what the ‘mother country’ was like. It was a public relations exercise by the Estado Novo, for in March that year the Government had passed an amendment to the controversial Colonial Act, renaming the colonies ‘Overseas Provinces’ and considering them an integral part of a far-flung Portuguese State. The change of nomenclature reinforced the one-nation theory, in a bid to counter global pressure against European colonization in the post-World War scenario.

The exercise paid dividends. Members of the delegation sent regular reports to their respective newspapers. On her return, Leonor wrote about what had impressed her, not forgetting the meeting with Premier Oliveira Salazar and the Minister for Overseas Territories, Sarmento Rodrigues. She had spoken to pressmen from continental Portugal and its overseas provinces on different aspects of life in Goa.

This was the first and surely the most memorable of her many visits abroad. Her official trip of 1956, on the fortieth anniversary of Salazar’s New State, was marked by the publication of her first book, Salteadores da Honra Alheia na Índia Portuguesa, (‘Assailants of People’s Honour in Portuguese India’). The curious little book’s arresting title and explosive content prompted the Portuguese Governor-General Paulo Bénard Guedes to have it confiscated on its arrival in Goa. While the author’s primary intention was to publicize the truth about her husband’s professional troubles, these are universalized, turning the book into a “repository of truths that make up our life in India.” The picture of a coconut tree and a cobra on its cover probably point to the coexistence of indolence and poison in our land. The evil doings of some prominent individuals and the shady workings of many a public institution are exposed.

Civil Rights Activist

Leonor was a champion of civil liberties by virtue of her journalism. As a proud descendant of one of Goa’s best known families involved in the civil rights movement, she took to it like fish to water. While critical of the administrative faults of the Portuguese regime, she was a moderate in her political aspirations, open to the ideas of decentralization and greater financial autonomy for Goa, emanating from the new Lei Orgânica do Ultramar, and more importantly a zealous protector of the Goan identity, in the pre- and post-1961 regimes. This was clear from her statement upon taking her seat in the legislative council of Portuguese India, in 1961: ‘Regimes fall, empires vanish, ideologies die, but the land remains, and we have to work for Goa to remain forever.”

Leonor was now left to fight life’s battles alone. She had lost her husband in 1960; and under the new political dispensation, even her journal had to change its name to A Índia – just ‘India’! She was smart enough not to grudge this, given the fait accompli of the Indian take-over of Goa. But what provoked her ire was that the Comunidades were being given short shrift, enough to have Martinho Fernandes turn in his grave.

In her second book, Contribuição para um Mundo Melhor, a tribute to her husband, printed on her last visit to Lisbon, in 1978, she addresses him on his life's interest, saying, "Do you see the state of our land today, how the Comunidades are faring, and how the land is groaning under injustice?" (p. 8) “Because our people are not rebellious and have not lost their sense of discipline and honesty, there has been no revolution yet,” she thunders (p. 14). It is clear that although she wishes to reconcile everything under a positive title (‘Contribution for a Better World’) nothing can camouflage her combative spirit.

Eye-opening Interview

![]()

In 1966, The Current, a well known weekly published from Bombay, invited readers to send in entries for an interview competition to mark the publication’s 18th anniversary. Leonor submitted her experiences as editor of A Índia. As one of the four short-listed, she was interviewed by the redoubtable D. F. Karaka, who, curiously, twenty-three years earlier, had been mentioned as one of her favourite authors. It was a rendezvous of two editors sans peur et sans reproche…

The picture of Leonor that accompanied her “interesting entry” was considered “almost as threatening as the entry itself”. On the morning of the interview, a tornado was expected to blow into the newspaper office, bearing a flaming torch in one hand and a sword in the other. Although Leonor fulminated against the police for searching her residence by night, looking for components of bombs and other subversive material used in the Vasco bomb case, “the tornado from Goa was only a gentle breeze”, wrote Karaka. Frustrated with their sole discovery, a book titled Invasion and Occupation of Goa (National Secretariat for Information, Lisbon, 1962), containing world press reports on the contentious Goa Question, her Indian passport was impounded when she was on a visit to New Delhi and, back in Goa, censorship was imposed on her paper, with a heavy bond and two sureties made necessary to ensure “due performance of the restrictions”.

The intrepid Goan journalist stated that “her fight was against all governments who tried to deprive the people of civil rights and who imposed censorship, whether it was a Portuguese censorship or the censorship dictated by the Indian Government.” She especially decried censorship under a democratic set-up. “I wanted to publish in my paper extracts from Inside, which is a Swatantra Party paper. These quotations were cut out by the censors,” she said.

Final Years

Some of her statements to the Bombay tabloid have a familiar ring even today: “The administration has gone rotten. In the (Goa) Assembly, the Opposition has accused the Government of nepotism, communalism, inefficiency and incompetence…. Laws have been passed without going into the constitutional right of the people,” she complained.

While she made a case for the preservation of the Goan identity, showing her red-pencilled extracts of Nehru’s speech at Siddharth Nagar, Bombay, on 4th June 1956, to redress her own grievance against the Government of Goa, she either met or wrote to Indira Gandhi every time. In her letter of 19th February 1966, she declared, “I believe in a Power above the powers of the world and in justice that comes, sometimes in time, at other times a bit late, in some manner or the other.” The restrictions were soon lifted, by a letter dated 13th May 1966, the significance of which day was not lost on Leonor: she was a great believer in the Message that the Mother of Jesus gave on this day, half a century earlier, in her apparition at Fatima, a place Leonor visited on several occasions.

Her meetings with Mrs Gandhi are recounted in Contribuição, which also carries interesting reflections on the period spanning 1961-78; her missives from Portugal, Angola and Mozambique (August-October 1969), which though “innocuous” were responsible for her passport problems yet again; historical snippets about her newspaper; the story of the legendary José Inácio de Loyola Sr.; and photocopies of historic telegrams of the tumultuous days of September 1890.

Karaka had found it “heartening to see a woman in her 50s, who had been so disturbed by the turmoil of politics, still crusading for the rights of the people and still having faith in a Power above the powers of the world.” Leonor was truly blessed with a deep and empowering faith – or else she would not have endured as a career journalist until December 1975. She said, “I have great faith in Our Lady. Although I have been harassed in my life by the powers on earth, I have never cared or worried.” And not surprisingly, when the Angel knocked at her door on 8th January 2005, he must have found Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, at the ripe old age of 95, still steadfast in her principles and faithful to her people.

(Herald, 'Mirror', Sunday magazine, 24.05.2009)

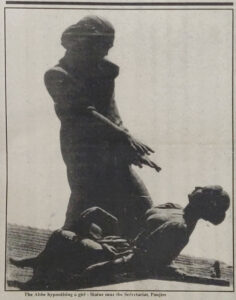

The Hypnotist in Holy Orders

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

Precious little remains till date in the memory of the average Goan. There is a statue of him in the capital city and a street takes his name in Margão. He has been forgotten in his native village of Candolim; only a primary school is named after him there and in some other villages too. He is almost unknown where he worked and lived – Lisbon, Paris and Marseilles. Only an obscure street is named after him in Marseilles.

People may not be apt to remember somebody who lived two centuries ago and with a mysterious sounding name such as Abbé Faria. But what if he has some original scientific contribution to his credit? Never mind that he was a theorist of hypnotism by suggestion, which has since become a vital aid to psychiatry, psychoanalysis and surgery. Very often his name is omitted when the subject comes to the fore. Not even does the Encyclopaedia Britannica refer to him as they do Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) and James Braid (1795-1860), who have only usurped his pride of place.

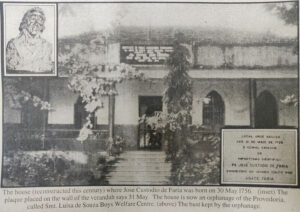

Such has been the fate of José Custódio de Faria (1756-1819), a priest and doctor of theology, who without any medical training did perceive and lend respectability to the true nature of what he called ‘sommeil lucide’ (lucid sleep). It was an intuition characteristic of a true genius. And for this original contribution to the field of science he is regarded at home as the greatest Goan that ever lived.

Early Life

José Custódio de Faria was born on 31 May 1756, to Caetano Vitorino de Faria of Colvale and Rosa Maria de Souza of Candolim. His father was a seminarian and had already received minor orders when he met and married Rosa, the only daughter of a rich landlord of Candolim. He was clever and she was rich, but the combination did not work out that well. Even their son born two years after their marriage, could not prolong their mutual love. Around the year 1764, they got a canonical decree of separation in 1764. He took holy orders and she joined the Santa Monica convent in the  old city of Goa.

old city of Goa.

No bonds linked them ever since. The father and the son stayed a few years at their friends in Candolim – the Pintos of the Conspiracy fame – and at Colvale too. On 21 February 1771, four years after being ordained a priest, Caetano Vitorino left for Lisbon, en route for Rome, to continue his priestly studies. He had similar intentions for his son. Their social circle in Goa and particularly a letter of recommendation they carried for the nuncio in Lisbon, Mgr. Inocencio Conti, won them access to the royal court. Moreover, the reigning monarch, Dom José I, and his prime minister, the Marquis of Pombal, were favourably disposed towards the Goans, whom they strongly recommended for civil, military and ecclesiastical positions at home.

Student in Rome

Thus José Custódio was awarded a scholarship to study in Rome. The father returned to Lisbon in 1777 on attaining a doctorate to further his objective of objective of being appointed the bishop of Goa. His great disappointment and frustration on this count determined much of what followed in his life and his son’s too.

José Custódio stayed on and was ordained on 12 March 1780. At 24 he completed his doctoral thesis titled Theologicae Propositiones: De Existentia Dei, Deo Uno et Divina Revelatione (Theological Propositions on the Existence of God, One God and Divine Revelation) and joined his father in Lisbon.

The duo were good friends but a different purpose animated them. Caetano Vitorino, the more political minded and diplomatic of the two, was fully immersed in matters Goan. He was a sort of self-appointed protector of and influential reference for the Goan community. The Court had been impressed by the fact that, though immensely influential at the highest levels of the kingdom’s administration, he had never asked favours for himself, though it was known that his personal finances were far from bright. But then, intelligence reports began to pin him down as the mastermind and coordinator in Lisbon of a political revolt at home in 1787. As soon as news of this reached Lisbon, they hunted for the duo and their good friends, clerics and laymen.

Meanwhile, all except Fr. Caetano Vitorino had fled to Paris, reportedly to meet and discuss with their envoys of Tipu Sultan, who proposed to be on the French side in their ascendancy against the British in India, but nothing was confirmed in this respect. Others believe that simpler reasons motivated Fr. José Custódio’s sudden departure – that he was attracted by the intellectual climate of France. His father did, however, stay back, still persevering in his designs and probably even overestimating his influence with the high officialdom. He was then put under house arrest in the Carmelite convent where he gave his priestly assistance, and probably died in 1799.

In Paris

Nothing is known of Fr. José Custódio’s activities in the French capital except that he was accused, in 1792, of being a gambler and frequenter of the Palais-Royale. He was acquitted, or at least no action was taken against him by the police. Three years later, on 5 October 1795, he led a battalion of revolutionaries against the National Convention. This political stand made him popular with the supporters of the Directoire and won him the friendship of the Marquis de Chastenet de Puységur.

The latter relationship was decisive. The Marquis had been a disciple of Mesmer whose quackish furrows into ‘animal magnetism’ and tall claims of cures had initially won him the acclaim of high Parisian society. But, in 1785, his exit was shameful. The Marquis, on the other hand, was an honest, well-meaning and cultured person, who took over from where Mesmer had left. Dr Egas Moniz, the Portuguese Nobel Prize Winner and biographer of Fr. José Custódio de Faria, speculates that he acquired knowledge of magnetism in Paris after he struck up an acquaintance with the Marquis.

The first news of Fr. Faria’s activity as a magnetizer is of the year 1802, in the memoirs of Chateaubriand (published in 1843), who referred to his experiments in derogatory terms. He had dined with Fr. Faria at the house of the Marchionesse of Custine. Here, Fr. Faria reportedly declared that he could kill a canary by magnetizing it. However, when the magnetizer was put to the test, he failed, which led Chateaubriand to conclude: ‘O Christian, my presence itself will be enough to make the tripod ineffective!’ Chateaubriand was a devout Catholic. He had strong reservations against magnetism – because of the Church’s attitude of suspicion towards it. But what is more is that Fr. José Custódio de Faria was a Catholic, no less!

Fr. José Custódio continued his research into the subject up to the year 1811, when he was appointed professor of Philosophy at the Academy of Marseilles. The Imperial Almanac of 1811 records that he lived there a year and was elected member of a medical society. Since he had no medical qualifications, the membership can only be attributed to his skills as a magnetizer. But for some mysterious reason, he was transferred, in fact, demoted, to the post of auxiliary professor at the Academy of Nimes. He felt slighted and frustrated and, unaccustomed as he was to life in a small city like Nimes, he returned to Paris, in 1813, in search of greener pastures. Unattached to any institution, he initiated his course in magnetism on 11 August 1813, 49, Rue de Clichy.

Sessions

The sessions were held every Thursday, on an admission fee of five francs only. He began with a lecture in halting French. The audience, which consisted largely of women, paid scant attention to this part of the session; their eyes were set on what was to follow – his experiments to substantiate his theory.

Contrary to the claims made by Mesmer, the he could control the body fluids of his patients and rectify their course through special methods invented by him, Fr. José Custódio very humbly put forth that not all individuals could be hypnotised, and that the degree of response to his hypnotic powers necessarily varied from person to person. He was the first to establish that hypnotism was a science of suggestion.

Fr. Faria’s method consisted of a series of well-reasoned and effective actions: he got the patient to sit comfortably and, through concentration, to relax, imagining that they were going to sleep. When the patient was ‘tranquil’, he gave the command, ‘Sleep!’ and, if necessary, repeated it, with a certain degree of urgency, three or four times. If he failed, he would either sportingly give up or try other methods.

The sessions became the rage of the town. There were detractors, critics and skeptics, no doubt. Once, a journalist attended his session and then unjustly criticised and ridiculed the priest in the press. At another session, a leading stage actor, Potier, offered himself for his experiments. He feigned to be in a trance and suddenly rose to say, ‘Ah, Abbé! If you magnetize others as well as you magnetized me, you don’t seem to be doing much.’

Fr. José Custódio put up very well with all such betrayals. He also withstood quite stoically criticism from the clergy and Rome, who then viewed his experiments with suspicion always on the look-out for diabolical influences therein. But the priest always expressed respect for the Church and a firm desire to stay within the Catholic fold. ‘Un esprit supérieur,’ as his disciple Gen. Noizet said of him, he wished to convince the Church that his experiments were fully within the natural realm and that there was no magic or witchcraft involved.

Thus, Fr. Faria took everything in its stride. Only once did he break down, when at Potier’s request the playwright Jules Verne put up a play, on 5 September 1816, the Variétés, titled La Magnétismomanie, ridiculing the Goan priest.

Sad end

The time was now ripe for Fr. Faria to stop his activities. He retired soon thereafter, rendering priestly services in exchange for boarding and lodging.

During the last years of his life, he decided to organize his material in book form. It was an ambitious project in four volumes, of which only the first one is known to have appeared. It is his magnum opus is titled De la cause du sommeil lucide ou Étude de la nature de l’homme (On the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study on the Nature of Man). In it he referred to the shameful play:

‘With regard to Magnétismomanie, I cannot ask which laws permit the modern Terence to expose an unknown foreigner to public ridicule. I presume that even the savage would be ashamed to insult his kind, which has nothing in common with actors and the theatre.

‘Far from me the idea to disturb public pleasures: But I might have added to Magnétismomanie a new scene – an extremely pungent one – had my condition not prevented me from doing so, and had my own aversion for such amusements not kept me away from playhouses.’

According to one biographer, by a strange coincidence, the day of his death, also marks the release of his book. His famous words, ‘There are evils that sometimes do good to those who discern their utility,’ might have very well served as his epitaph – if only he had the money for a decent burial. He died at the age of 63, unsung as he was born. A life full of ironies, for born of a rich family he died poor; born of parents who were in love, they separated after his birth; a man with original contributions to posterity, he died with no godfathers to promote his name.

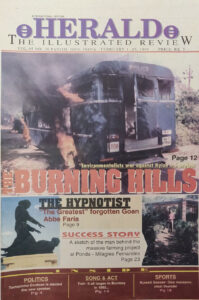

(Herald Illustrated Review, Panjim, Goa. Vol. 95, No. 30, February 1-15 1995. Slightly updated version)