A Última Conversa com Percival Noronha

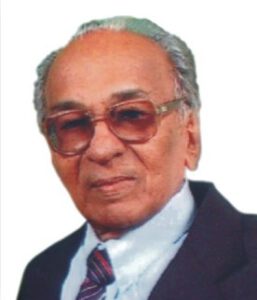

Numa tarde chuvosa (1 de Julho do ano passado), quando de súbito me lembrei do Sr. Percival Noronha[1], não hesitei em terminar a minha sesta dominical. Um distinto cavalheiro – culto, agradável, e que me estimava – daí a dias iria completar a bonita idade de 95 anos… Urgia, pois, falar com o grand old man de Pangim.

Quando liguei para a sua casa, ouvi logo um ‘Estou!’ inconfundível. Na linguagem do Sr. Percival, esse estar era o mesmo que estar disponível! ‘Pode o Óscar vir quando quiser’, disse com a amabilidade que o caracterizava. Estava sempre pronto para um papo, e desta vez seria como nunca dantes: radiodifundida na minha rubrica mensal, Renascença Goa… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRK2PimgTmo) Saí então rumo às Fontaínhas, acompanhado do meu irmão Orlando que trataria das fotos.

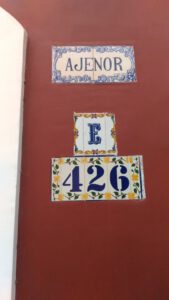

Era um prazer ir à residência do Sr. Percival (‘Ajenor’, nº E-426, à Rua Cunha Gonçalves). Também nos cruzámos, por centenas de vezes, em concertos, conferências, exposições de arte, e não menos em casamentos e funerais. Um senhor da velha guarda, era cumpridor dos seus deveres sociais e cívicos. Apesar da nossa diferença etária, a conversa corria como um rio de águas claras, pois o Sr. Percival era não só envolvente mas também apreciador dos méritos dos seus contemporâneos e estimulador dos talentos dos mais novos.

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Diga-se de passagem que eu admirava o seu automóvel, preto, parecendo sempre novo, tal como o seu proprietário. Este, sempre vestido de bush shirt ou camisa safari, percorria os cantos e recantos da cidade, que conhecia como a palma da sua mão. É que Percival e Pangim se pertenciam um ao outro: foi dos melhores cronistas da capital, do seu ethos e do seu ritmo, que descreveu em bela prosa.[2] E fê-lo com autoridade, mesmo porque presenciou nove décadas, ou seja, metade da história dessa urbanização,[3], de forma que hoje se torna difícil imaginar o nosso Pangim sem o Sr. Percival Noronha.

Cargos oficiais

Feitos os estudos liceais na capital, o Sr. Percival Noronha entrou para a administração pública, em 1947. Trabalhou, primeiro, nas Obras Públicas, passando depois para os Serviços da Estatística e Informação. Quando esta foi desagregada, o distinto professor e escritor António dos Mártires Lopes levou-o consigo para os novos Serviços de Turismo e Informação de que este acabava de ser nomeado chefe. O Sr. Percival nunca se esqueceu dos belos tempos do Liceu e do funcionalismo que passou sob a alçada directa desse seu antigo professor liceal: confessava que essa relação fora fundamental em nutrir a sua paixão pela história e cultura.

Quando se deu a mudança do regime politico, em Dezembro de 1961, o Sr. Percival era chefe-adjunto dos Serviços da Informação, reportando ao governador-geral Vassalo e Silva. Em Junho de 1980, a visita do simpático governador coincidiu com as comemorações do 4.º centenário da morte de Luís de Camões em Goa. Vinha a título pessoal, mas nem por isso a visita deixou de suscitar controvérsia.

Decorreu-se o pior da cena no Azad Maidan (‘Largo da Liberdade’), a antiga Praça Afonso de Albuquerque. Aqui, à certa distância, vi o antigo governante a ser interpelado por alegados actos de comissão e omissão do regime português em Goa.[4] O embaraçoso incidente atalhou-o o Sr. Percival Noronha, que, na qualidade de chefe de Protocolo do Território de Goa,[5] estava incumbido de acompanhar o ilustre visitante.

Antes dessa data, com a limitada bagagem de conhecimentos de inglês auferidos no Liceu, e língua essa que logo veio a dominar, o Sr. Percival Noronha ocupou outros cargos importantes na administração indiana. Foi sub-secretário das indústrias, minas, trabalho, saúde e turismo. Entre muitas outras iniciativas suas, os hospitais do Asilo em Mapuçá e o Hospício de Margão passaram a subordinar-se à Direcção de Saúde. Desenvolveu as zonas de Calangute, Colvá, Mayém e Farmagudi, e ideou os desfiles do Carnaval e Xigmó; teve papel preponderante no arruamento Campal-Miramar e na arborização do Parque Infantil; e foi um dos responsáveis pela realização da grande Feira Agrícola em 1970. Ora, possuidor dum raro espírito de autocrítica, não ocultava as faltas que houvera no planeamento e execução dessas suas propostas.

Não admira que o Sr. Percival Noronha tivesse sido um solteirão muito cobiçado. Passou, porém, a vida a cuidar da veneranda mãe, vindo a aposentar-se apenas um ano após a sua morte. Era igualmente dedicado à vida burocrática, passando horas a fio à mesa do gabinete, até para além das horas regulamentares. Um funcionário desse quilate podia facilmente esquecer-se de si próprio, como foi, na verdade, o caso do Sr. Percival Noronha.

Vida de aposentado

Teria sido diferente a sua vida depois de aposentado em 1981? Mudou de actividade, sim, mas o expediente não mudou de volume. Dedicou-se, a tempo inteiro, às matérias por que tinha propensão natural: a arte, a história e a astronomia.

Começou por dotar a sua residência com mobiliário de estilo tipicamente indo-português. Efectuou-se grande parte dessa obra no rés-do-chão do seu prédio, o qual havia sido confiado ao conhecido carpinteiro Zó. Disse-me, em mais de uma ocasião, que gastara nisso quase todas as suas economias. Também é verdade que todo dinheiro lhe era pouco quanto se tratasse de comprar objectos de arte e livros.[6] Assim, a casa se viu transformada em verdadeiro museu-arquivo que deveras honra o histórico bairro das Fontaínhas.

O Sr. Percival não parou por aí: tomou a peito vários assuntos de interesse público. Inspirado pelo alto funcionário (e depois governador) K. T. Satarawala, no ano de 1982 abriu um ramo da Indian Heritage Society em Goa e foi professor convidado da Faculdade de Arquitectura. Exerceu o cargo de secretário daquela organização não-governamental que, em colaboração com a Town and Country Planning Department, preparou um relatório sobre os prédios e sítios de importância arquitectónica no território de Goa. Foi também tesoureiro do INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) em Goa.

Esses organismos continua a desempen har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

Embora o Sr. Percival Noronha fosse indiferente em matéria religiosa, nunca hostilizou a Igreja. Pelo contrário, reconhecendo o papel desta no progresso espiritual e material dos povos, colaborou com as entidades eclesiásticas. Em 1986, quando da visita do Papa João Paulo II, participou entusiasticamente na preparação do evento. E, em 1994, foi membro fundador do Museu de Arte Cristã que ora se acha no Convento de S. Mónica.

Esse goês de gema era um arco-íris de saberes, tratando tanto da arqueologia como da astronomia com a mesma facilidade. Fundou a Association of Friends of Astronomy (AFA)[10], em 1982. Este organismo, além de vir a publicar uma revista mensal, Via Lactea, editada pelo fundador, abriu, em 1990, um observatório astronómico público – o primeiro do seu género na Índia – com o apoio do Departamento de Ciência, Tecnologia e Meio-Ambiente, do Estado de Goa.

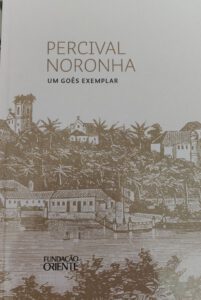

O Sr. Percival Noronha viveu uma vida sem artifícios – plain living and high thinking. Foi um líder cultural que criou à sua volta uma pleiade de jovens com decidida propensão pela história, arqueologia, arte e astronomia. Na sua casa, onde funcionavam os dois organismos que criou, recebia jornalistas, pesquisadores e outra gente interessada. Teimava em alertar a geração nova sobre o grave estado de bancarrota civilizacional em que a sua amada Goa estava a descambar. Esses recursos humanos e hábitos salutares sendo o maior legado do Sr. Percival Noronha, tem razão a Fundação Oriente em apelidá-lo de “Um Goês Exemplar”, num livro que publicou em sua homenagem.

Na verdade, é a vida intelectual que o entusiasmava, contribuíndo também para a sua saúde física. A sua roda de amigos da velha data[11] nutria a saudade pelo passado enquanto a geração nova o desafiava com projectos futuristas. Era um desses amicus certus, que tratando-se de algum sem-vergonha, falava, tipicamente, com ironia e sorriso escarninho. Mas não vou sem frizar que a todos desejava o bem, e para uma vida saudável recomendava-lhes uma medida de moog grelado por dia! Antes da prótese da anca, em Abril deste ano, esteve relativamente lúcido e ágil.

Última conversa

96 anos da vida. Dir-se-ia mesmo que o Sr. Percival Noronha teve sete vidas. Nos últimos anos era seu costume, quando adoecesse, anunciar a sua morte e daí a dias estar em pé! Era como que tivesse um sistema imunológico como o do gato persa, de que gostava. Não era motivo para recear, pois, quando ouvi de novo que o Amigo estava em declínio. Tive, porém, empenho em conversar com ele demoradamente.

Às 4,30 da tarde, o Sr. Percival tinha já à mesa o bule de chá e bolachas. Dormira a sesta e estava pronto para uma conversa. A rapariga, às ordens, sentada lá no fundo da sala. E parecia tudo como dantes...

Foi quando notei que o venerando ancião tinha o cabelo despenteado, a barba por fazer, e faltava-lhe a placa de dentes. Nunca o vira assim… Os apetrechos de trabalho estavam lá todos, arrumadinhos, nas estantes e armários, dum lado da sala de jantar, onde costumava passar grande parte do tempo a trabalhar. Também isso não estava como dantes... E reflecti também que desta vez o meu anfitrião que viera ele à janela, como era seu costume, deitando para mim a chave da porta principal… Tudo isso indicava que a sua vida ia afrouxando. Fiquei triste.

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

No entanto, ia falando sobre o seu currículo escolar e profissional; as suas actividades depois de aposentado; sobre Salazar (cuja inteligência e honestidade admirava) e o 18/19 de Dezembro; a administração, portuguesa e indiana; os cursos e conferências que realizou nas universidades da Ásia e Europa; o futura da língua portuguesa em Goa; a cultura goesa e a distorção da sua história; os seus amigos e as pessoas que admirava; e a vida em Pangim: tudo isso, entre muitos outros assuntos, e não necessariamente nessa ordem de ideias.

Nos últimos meses, vi-o, várias vezes, debruçado no peitoril da varanda, qual abencerragem a observar a vida que corria lá fora, e com a cara de quem pensa: Quantum mutatis ab illo… Barbudo, lembrava Abraão, personagem de primordial importância para as comunidades à sua volta. E com aquele cabelo a voar e ele a fitar o firmamento, assemelhava-se à figura de Einstein…

Também lá do alto do Céu ouvirá – no último domingo do mês de Novembro deste ano – a última entrevista que concedeu cá na terra. Foi a minha última conversa com o Sr. Percival Noronha.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] De nome completo, Percival Ivo Vital e Noronha (26.7.1923 –19.8.2019), filho de António José de Noronha, de Loutulim, e de Aurora Vital, de S. Matias.

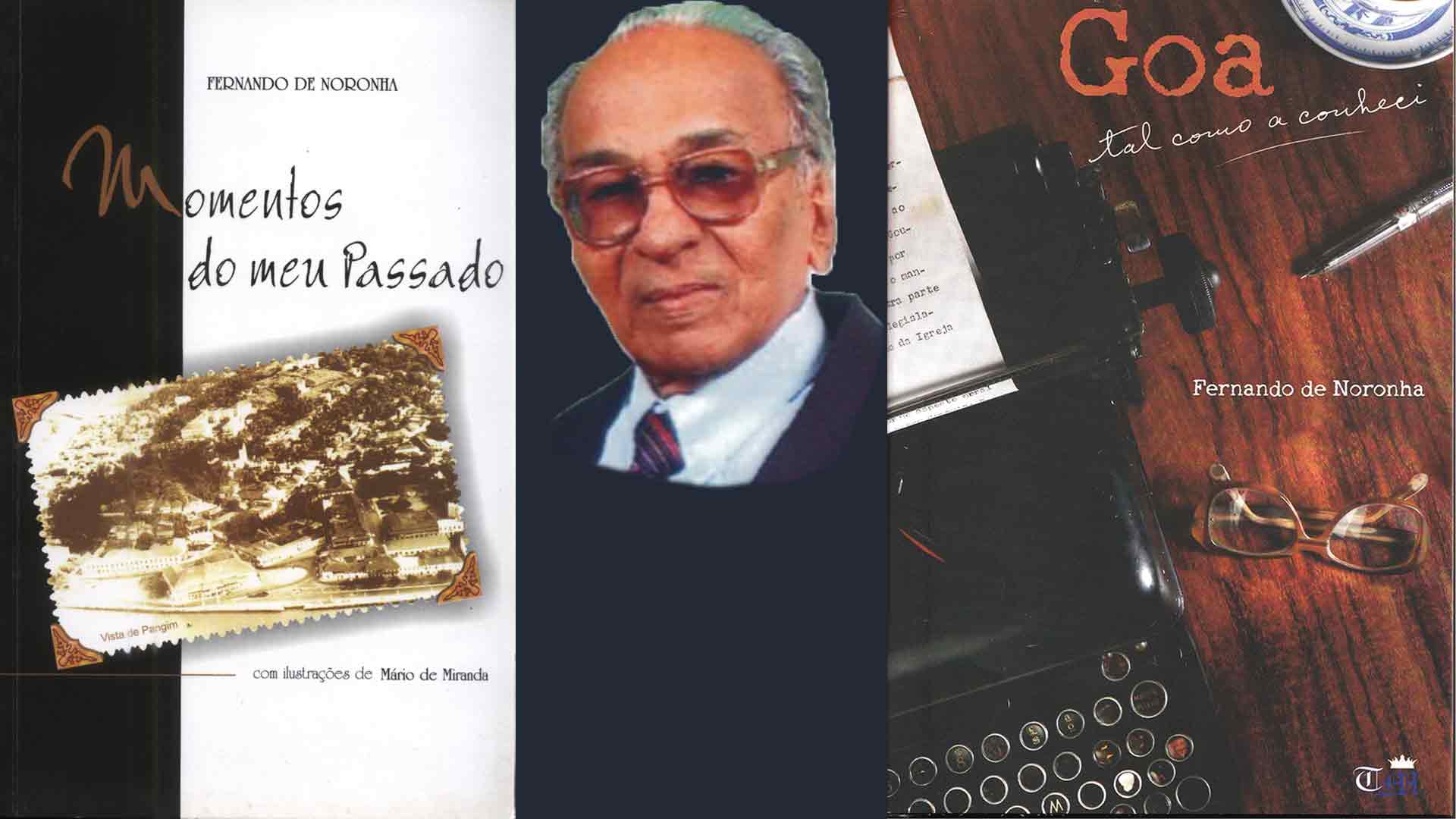

[2] “Panjim: Princess of the Mandovi” (2002); “Fontaínhas: vivendo com o passado”(2001); “Fontaínhas: the Tale of Panjim’s Latin Quarter” (2003), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015)

[3] A vila de Pangim foi elevada à cidade com a denominação de Nova Goa, por alvará de 22 de Março de 1843, o qual lhe outorgou todos os privilégios de que gozavam as cidades de Portugal Continental.

[4] O incidente impulsionou a minha primeira intervenção jornalística em forma de uma carta ao director dum jornal de Pangim – “Our Honoured Guest”, in The Navhind Times, 12/6/1980.

[5] Na altura, cumulava este cargo com o de director da administração das Obras Públicas.

[6] Doou a sua casa ao sobrinho Francisco Lume Pereira, de Verna, onde Percíval Noronha faleceu, e os livros doou-os à Universidade dos Açores e à Krishnadas Shama Library, de Pangim; e os diapositivos, ao Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino.

[7] “Christian Art in Goa” (1993); “Indo-Portuguese Furniture and its Evolution” (2000); “Priceless Christian Art” (2004), e “Goan Artisans” (2008), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[8] “Levantamento arqueológico da Velha Goa e tentativas para a sua conservação” (1989); “Old Goa in the context of Indian heritage”(1997); “Um passeio pela Velha Cidade de Goa”(1999); “A Capela de Nossa Senhora do Monte, em Velha Goa” (2001), ), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[9] Recebeu ao todo 16 galardões de proveniência vária.

[10] http://afagoa.org/about_us.html

[11] Entre outros, António dos Mártires Lopes, Aleixo Manuel da Costa, Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes, Alcina dos Mártires Lopes, Artur Teodoro de Matos, Luís Filipe Thomaz, Teotónio de Souza, Rafael Viegas, Nandakumar Kamat, Satish Naik.

[12] Tradition and Modernity in Eighteenth-Century Goa (Manohar, New Delhi & Centro de HIstória de Além-Mar, Lisboa, 2006)

[13] Old Goa: A Complete Guide (Panjim: Third Millennium, 2004)

[14] Castilho de Noronha: por Deus e pelo País (Panjim, Third Millennium, 2018)

Fotos de Orlando de Noronha, com excepção da da condecoração (e-cultura.pt) e da do lançamento do livro (Fundação Oriente)

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série, Número 1, Maio/Dezembro de 2019 https://issuu.com/jmm47/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n1_-_maio-dez_

Tribute to my Father

Early this month the social media was abuzz, in anticipation of the twenty-twenties; as for me, I was on a solo trip back to nineteen-twenty. As a child, this year had the earmarks of a happy milestone for me, yet it triggered anxiety for the future. My childhood was a shrine of happy pictures, yet the thought of that golden marker fading into the horizon would fill me with sadness. Why? Because while a young me was looking ahead to what would be, my father Fernando was already looking back upon what had been….

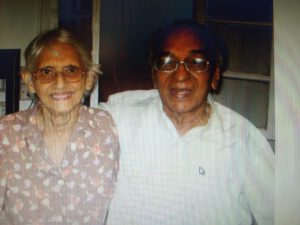

My lone source of anxiety for the future was that I was the eldest child, born in Papa’s forty-fourth year. I knew not how long I would have him: it was a worry I kept to myself so as not to dishearten him. But then, hardly anything disheartened him; he kept pace with his children and even his grandchildren’s progress, and enjoyed the sleep of the just. When he passed on, at 91, he was a grandfather to fifteen. His abiding trust in God was the secret of his longevity – as well as a salutary lesson on the futility of anxiety.

In my naiveté, 1920 still felt charming; as I grew older, I found Papa’s idealism, independence and integrity appealing. I looked up to him, especially because his life hadn’t been easy: the ‘roaring twenties’ of the West had played out quite differently in Portugal and Goa. Following a decade of political turbulence and galloping inflation, the country stabilised and the escudo roared upon the rise of Salazar the economist. Convinced that he was a man with ‘the right intention’, my father held him in esteem for his intellect and honesty – the antithesis of leaders in sham democracies.

After God, it was Goa uppermost in Papa’s mind. The Mass and the Bible alongside spiritual classics were his daily fare. To compensate for arid bureaucratic matters, he put his faith in reading, writing, teaching and music. Even while he took delight in the Romantics Eça, Camilo and Ramalho, he recommended some excellent Goan writers. Until his last breath he lapped up the masters of the Portuguese language, not forgetting two of our very own Goan purists, Costa Álvares and Filinto C. Dias.

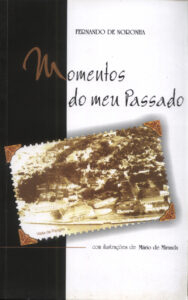

One gets a bird’s eye view of Papa’s outlook from his first book, Momentos do meu Passado (Moments from my Past). Much of it is what he used to recount animatedly at the dinner table or talk over with relatives and friends. He obliged us by writing this slim volume comprising ‘figures, facts and facetiae’: pen sketches of over thirty personalities from the Goan social and political milieu; some little-known facts of contemporary history; and a host of anecdotes dating back to his Lyceum days. In his words, he wished ‘to quench saudades of a not so distant past, when one lived in a happy and carefree manner unique to Goa.’

It took me some time to appreciate Papa’s simple and straightforward nature. And noticing how people would often agree but also end up severing ties with him, I learnt that truth can indeed puzzle, confound, hurt… Papa’s intermittent observations on public affairs are lost in the thicket of Heraldo and A Vida for, whilst a bureaucrat in two key departments during the Portuguese regime, he used pen names of which he kept no record. In 1967, his commitment to ferry people to the booths on the occasion of the Opinion Poll (16 January, his birthday and feast of St Joseph Vaz) fetched him a resounding office memo.

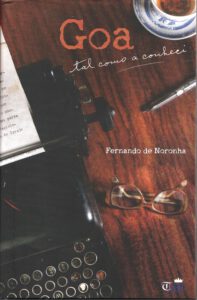

It warms the cockles of our hearts to see that Papa’s second book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), contains the essence of his views on people, events and ideas. Covering as he did twentieth-century Goa’s political and administrative affairs, society, culture, and religion, in a total of eighteen chapters, this offering is a testimony of love for the land and the people. It is also a tribute to the Portuguese language that was so dear to him. After opting to retire from public service, he taught that idiom at a city college and co-founded a weekly, A Voz de Goa. At Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church he prayed in that ‘language of the angels’ and put together a choir at Sunday mass.

Music was high up on his agenda ever since his father purchased a gramophone and a maternal uncle and self-taught violin virtuoso played along. An attractive feature of Papa’s day was his whistling and playing of the harmonica, providing the household with a kind of crash course in classical and semi-classical music. The mandó moved him very especially (he ensured that it featured at his children’s wedding parties) and so did two popular Konkani films of his time which, he said, ‘foster Goan patriotic feelings’. The Goan reality, however, was a far cry from what he had envisioned, so I can say with Wodehouse that ‘if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.’

No tribute to our father would be complete without a reference to our dearest mother Judite da Veiga, who was the love of his life, the reason of his being. On his death bed I heard him thank her for half a century of togetherness. She, their five boys and families, was all that he ever wanted. We have lost him in body, not in spirit. He has become greater in death, our strength and consolation, our conviction that there can be no anxiety for the future….

Herald, 19.01.2020, published an abridged version

For this full version see Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), March-April 2020

https://issuu.com/casadegoa/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n3_-_mar-abr_2

Remembering Leonor: Editor Extraordinaire

To the dead it probably matters little whether or not they are remembered: having done their bit on earth they now belong to Eternity, where worldly honour and glory are of no consequence. But paying them homage is a cardinal civic virtue – an expression of gratitude for the valuable services rendered by them to the community, which also helps to imbibe sterling values that might well be scarce in a new day and age.

That is what links us to Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes on her birth centenary. Born on 24th May 1909 to Miguel de Loyola Furtado of Chinchinim and Maria Julieta de Loyola of Orlim, she was married to Martinho António Fernandes of Colvá. She was a woman of many parts but essentially a matriarch and a grand lady of the Fourth Estate.

Wife and Mother

Leonor – Lolita, in her close circle – was a person ahead of her times. She was a career woman with a difference. When the Panjim-based eveninger Diário da Noite (2nd May 1953) asked about the beginning of her occupation, she said, ‘I don’t remember clearly when I started writing. I know I became a mother at 16 and it must have been after this that I began writing in earnest.’

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

This candid statement of fact was also a reflection of her priorities. No doubt it was a man’s world but as a gifted woman she had found her way out. Talking to me (Herald Mirror, 15th September 1996), she said that her professional work never disturbed her duties as a housewife, “because my husband was an intelligent man with humanistic interests at heart. He never interfered in my work as I never did in his. There was a lot of mutual understanding. He gave me the courage to fight for my ideals – even though it might have reflected on him as a government official.”

And reflect it did. As Administrator of the Comunidades of Salcete, Martinho Fernandes, a lawyer by training, was dogged by controversy, initially fomented by individuals who eyed his post, while later some of it was fuelled by a heady mix of personal vengeance and political vendetta, thanks to his wife’s plain speaking in the weekly A Índia Portuguesa. The incumbent emerged unscathed, through long and tortuous battles up to the apex court.

It must not have been easy for Leonor to weather those storms while she raised four daughters, managed the household chores and the family estates. But the years rolled by and, interestingly, at 39 years of age, she was already a grandmother! In 1950, when that venerable journal, a family heirloom and historic mouthpiece of the pro-native political party called Partido Indiano, founded by the Loyolas of Orlim, was almost folding up, it was born again with Leonor.

Journalist and Author

It was for the first time that in the whole of the Portuguese speaking world and in the Indian sub-continent as well a woman was at the head of a newspaper. This was only a natural consequence of having her father for a role model: apart from being a brilliant physician and political leader, he had edited A Índia Portuguesa from the year 1912 until his sudden demise in 1918, and his memory remained with Leonor for the rest of her days. She once said, ‘If destiny were not opposed to it, I would have studied medicine. I had a fascination for the medical profession, so as to positively spread the good to all. But I was born for something else – and I am a journalist only. I would have liked to be a physician and journalist.’ (Diário da Noite)

A year after assuming editorship she travelled to Portugal, the only lady in a Goan media delegation comprising Fr Manuel Francisco Lourdes Gomes, Álvaro de Santa Rita Vaz, Amadeu Prazeres da Costa and Luis de Menezes Jr. They had been invited for a month’s stay, to see for themselves what the ‘mother country’ was like. It was a public relations exercise by the Estado Novo, for in March that year the Government had passed an amendment to the controversial Colonial Act, renaming the colonies ‘Overseas Provinces’ and considering them an integral part of a far-flung Portuguese State. The change of nomenclature reinforced the one-nation theory, in a bid to counter global pressure against European colonization in the post-World War scenario.

The exercise paid dividends. Members of the delegation sent regular reports to their respective newspapers. On her return, Leonor wrote about what had impressed her, not forgetting the meeting with Premier Oliveira Salazar and the Minister for Overseas Territories, Sarmento Rodrigues. She had spoken to pressmen from continental Portugal and its overseas provinces on different aspects of life in Goa.

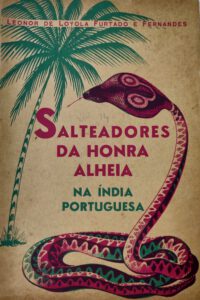

This was the first and surely the most memorable of her many visits abroad. Her official trip of 1956, on the fortieth anniversary of Salazar’s New State, was marked by the publication of her first book, Salteadores da Honra Alheia na Índia Portuguesa, (‘Assailants of People’s Honour in Portuguese India’). The curious little book’s arresting title and explosive content prompted the Portuguese Governor-General Paulo Bénard Guedes to have it confiscated on its arrival in Goa. While the author’s primary intention was to publicize the truth about her husband’s professional troubles, these are universalized, turning the book into a “repository of truths that make up our life in India.” The picture of a coconut tree and a cobra on its cover probably point to the coexistence of indolence and poison in our land. The evil doings of some prominent individuals and the shady workings of many a public institution are exposed.

Civil Rights Activist

Leonor was a champion of civil liberties by virtue of her journalism. As a proud descendant of one of Goa’s best known families involved in the civil rights movement, she took to it like fish to water. While critical of the administrative faults of the Portuguese regime, she was a moderate in her political aspirations, open to the ideas of decentralization and greater financial autonomy for Goa, emanating from the new Lei Orgânica do Ultramar, and more importantly a zealous protector of the Goan identity, in the pre- and post-1961 regimes. This was clear from her statement upon taking her seat in the legislative council of Portuguese India, in 1961: ‘Regimes fall, empires vanish, ideologies die, but the land remains, and we have to work for Goa to remain forever.”

Leonor was now left to fight life’s battles alone. She had lost her husband in 1960; and under the new political dispensation, even her journal had to change its name to A Índia – just ‘India’! She was smart enough not to grudge this, given the fait accompli of the Indian take-over of Goa. But what provoked her ire was that the Comunidades were being given short shrift, enough to have Martinho Fernandes turn in his grave.

In her second book, Contribuição para um Mundo Melhor, a tribute to her husband, printed on her last visit to Lisbon, in 1978, she addresses him on his life's interest, saying, "Do you see the state of our land today, how the Comunidades are faring, and how the land is groaning under injustice?" (p. 8) “Because our people are not rebellious and have not lost their sense of discipline and honesty, there has been no revolution yet,” she thunders (p. 14). It is clear that although she wishes to reconcile everything under a positive title (‘Contribution for a Better World’) nothing can camouflage her combative spirit.

Eye-opening Interview

![]()

In 1966, The Current, a well known weekly published from Bombay, invited readers to send in entries for an interview competition to mark the publication’s 18th anniversary. Leonor submitted her experiences as editor of A Índia. As one of the four short-listed, she was interviewed by the redoubtable D. F. Karaka, who, curiously, twenty-three years earlier, had been mentioned as one of her favourite authors. It was a rendezvous of two editors sans peur et sans reproche…

The picture of Leonor that accompanied her “interesting entry” was considered “almost as threatening as the entry itself”. On the morning of the interview, a tornado was expected to blow into the newspaper office, bearing a flaming torch in one hand and a sword in the other. Although Leonor fulminated against the police for searching her residence by night, looking for components of bombs and other subversive material used in the Vasco bomb case, “the tornado from Goa was only a gentle breeze”, wrote Karaka. Frustrated with their sole discovery, a book titled Invasion and Occupation of Goa (National Secretariat for Information, Lisbon, 1962), containing world press reports on the contentious Goa Question, her Indian passport was impounded when she was on a visit to New Delhi and, back in Goa, censorship was imposed on her paper, with a heavy bond and two sureties made necessary to ensure “due performance of the restrictions”.

The intrepid Goan journalist stated that “her fight was against all governments who tried to deprive the people of civil rights and who imposed censorship, whether it was a Portuguese censorship or the censorship dictated by the Indian Government.” She especially decried censorship under a democratic set-up. “I wanted to publish in my paper extracts from Inside, which is a Swatantra Party paper. These quotations were cut out by the censors,” she said.

Final Years

Some of her statements to the Bombay tabloid have a familiar ring even today: “The administration has gone rotten. In the (Goa) Assembly, the Opposition has accused the Government of nepotism, communalism, inefficiency and incompetence…. Laws have been passed without going into the constitutional right of the people,” she complained.

While she made a case for the preservation of the Goan identity, showing her red-pencilled extracts of Nehru’s speech at Siddharth Nagar, Bombay, on 4th June 1956, to redress her own grievance against the Government of Goa, she either met or wrote to Indira Gandhi every time. In her letter of 19th February 1966, she declared, “I believe in a Power above the powers of the world and in justice that comes, sometimes in time, at other times a bit late, in some manner or the other.” The restrictions were soon lifted, by a letter dated 13th May 1966, the significance of which day was not lost on Leonor: she was a great believer in the Message that the Mother of Jesus gave on this day, half a century earlier, in her apparition at Fatima, a place Leonor visited on several occasions.

Her meetings with Mrs Gandhi are recounted in Contribuição, which also carries interesting reflections on the period spanning 1961-78; her missives from Portugal, Angola and Mozambique (August-October 1969), which though “innocuous” were responsible for her passport problems yet again; historical snippets about her newspaper; the story of the legendary José Inácio de Loyola Sr.; and photocopies of historic telegrams of the tumultuous days of September 1890.

Karaka had found it “heartening to see a woman in her 50s, who had been so disturbed by the turmoil of politics, still crusading for the rights of the people and still having faith in a Power above the powers of the world.” Leonor was truly blessed with a deep and empowering faith – or else she would not have endured as a career journalist until December 1975. She said, “I have great faith in Our Lady. Although I have been harassed in my life by the powers on earth, I have never cared or worried.” And not surprisingly, when the Angel knocked at her door on 8th January 2005, he must have found Leonor de Loyola Furtado e Fernandes, at the ripe old age of 95, still steadfast in her principles and faithful to her people.

(Herald, 'Mirror', Sunday magazine, 24.05.2009)

Our Honoured Guest

The directive from the Union Home Ministry to give the loving last Portuguese Governor-General, General Manuel Antonio Vassalo e Silva, a “warm welcome” and a “foreign dignitary VIP treatment” is to be admired as the Government showed their love and respect to that person who earlier pictured his fine sensibilities to Goans whom he so dearly loves.

But, at the same time, there seemed to be a few of our own people who although owing so much to Gen. Vassalo tried to misunderstand the Government: A “warm welcome” (the Government’s call) doesn’t only mean giving a beautiful bouquet of flowers to the visitor at the airport but still more, it emphasizes the need for a good treatment during his stay in this place.

Although all plans for a “warm welcome” were made well in anticipation by our Speaker, Mr Froilano Machado, there was something unhappy awaiting Gen. Silva at the Azad Maidan, when he went there to place a wreath at the Martyrs’ Memorial, much to the surprise and dislike of hundreds of Goans worthy of Mr Silva’s kindness: it was a dharna, a protest with black flags against the ex-Portuguese Governor-General’s visit to Goa; he who did so much good for us Goans. That should not even have been thought of because Gen. Silva was invited by Goans who intend to manifest their love and gratitude towards him. Secondly, what has Mr Silva to do with the integration of Goa into the Indian Union? Is Mr Silva responsible for Salazar’s misdeeds?

On the other hand, if any Goan had to open his heart and say something genuine against the Portuguese he would have done so or should have done so by approaching Gen. Silva in a very gentlemanly manner and not by what we witnessed at the Azad Maidan. This sort of behaviour from the Goans who are known for their non-aggressiveness and kindness is unthinkable.

Keeping aside the misbehaviour of a handful of people, I would like to mention that there were many also who openly showed their consideration for the Portuguese: one was an aged woman who respectfully wished the popular ex-Governor-General who then spoke very emotionally to her. A few steps further, some others waited to salute and talk to the octogenarian, who recalled his good old days with them in Goa.

We congratulate Gen. Vassalo e Silva who gave out the truth that Salazar didn’t ask him to destroy but to “defend it to the last”. This will remove the misconceptions about the affair.

Kudos to the editorial which has described Gen. Silva very well as a man to whom we ought to be grateful.

(Letter to the editor, The Navhind Times, Panjim, 12 June 1980, p. 2)